Abstract

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a well-defined syndrome characterized by the presence of nephrotic range of proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperlipidemia. Although venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a well-reported complication associated with NS, the incidence, prevalence, risk factors, treatment options, and preventative strategies are not well-established. Thromboembolic phenomena in nephrotic patients are postulated to be a result of the urinary loss of antithrombotic factors by affected kidneys and increased production of prothrombotic factors by the liver. Most cases of VTE associated with NS reported in the literature have a known diagnosis of NS. We report a case of a young female presenting with dyspnea and a pulmonary embolism. She was found to have NS and right renal vein thrombosis. We review the available literature to highlight the best approach for clinicians treating VTE in patients with NS.

Keywords: Deep venous thrombosis, nephrotic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, renal vein thrombosis, venous thromboembolism

INTRODUCTION

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is defined by the presence of nephrotic range of proteinuria, peripheral edema, hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia and increased risk of VTE complications. It is classified as either primary or secondary with membranous nephropathy, minimal change nephropathy and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis included in the primary causes. Secondary causes can be further subdivided into two subsets, NS related to systemic disease and NS related to medication use. NS related to systemic disease includes diseases like diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple myeloma and malignancy. The most common medication implicated in NS is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Although increased incidence of VTE is a well reported complication associated with nephrotic syndrome, the incidence, prevalence, risk factors and management strategies are not well established.[1]

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old female presented to the emergency room with dyspnea and substernal chest pain. She had no significant medical history. She was found to be tachycardic, tachypneic, and hypoxemic. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest demonstrated bilateral acute pulmonary embolism (PE). She was also found to have mild troponin elevation with no signs of right heart strain on echocardiogram. She was admitted to the hospital and started on low molecular weight heparin and warfarin. She was a nonsmoker, was moderately active, and had no known malignancy. During her hospital stay, she experienced some abdominal discomfort. A urinalysis revealed proteinuria, and a 24 h urine collection showed proteinuria >7.2 g/day. A CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated a right renal vein thrombosis (RVT). Laboratory work showed normal complement levels (C3 and C4), antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antiglomerular basement membrane antibody, and negative hepatitis B and C serologies. A kidney biopsy revealed membranous glomerulonephritis. She was then referred to the nephrology service for further management of nephrotic syndrome (NS).

DISCUSSION

NS is defined by the presence of nephrotic range of proteinuria, peripheral edema, hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, and has an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). It is classified as either primary or secondary. Membranous nephropathy (MN), minimal change nephropathy, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis are the primary causes. Secondary causes include NS related to systemic disease and NS related to medication use. NS related to systemic disease includes diseases such as diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple myeloma, and malignancy. The most common medications implicated in NS are the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Although VTE is a well-reported complication associated with NS, the incidence, prevalence, risk factors, and management strategies are not well-established.[1]

Epidemiology

The exact incidence and prevalence of VTE in NS remain unknown. Varying rates are reported in different studies. The variance in reported incidence and prevalence rates has been attributed to the limited data available, perhaps from underdiagnosis in this patient population.

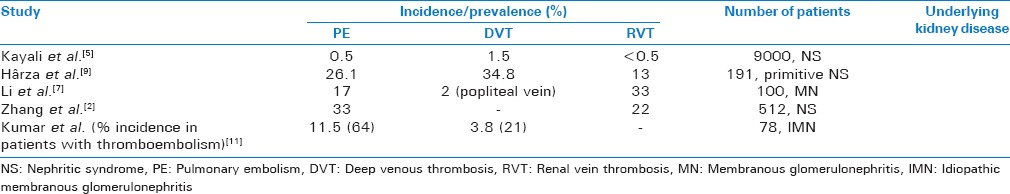

In a prospective study by Zhang et al., 512 patients with NS underwent CT pulmonary angiography for PE and renal CT venography for RVT. One hundred and eighty of the 512 patients (35%) had PE and/or RVT. Of these, 153 patients had PE and 85 of the 153 (56%) patients had associated RVT with PE. They found PE to be more common that RVT in nephrotic patientsand most patients were asymptomatic (84%).[2] Medjeral-Thomas et al. report that VTE occurs in 7–40% of NS patients and the prevalence of VTE in patients with MN is increased as compared to other forms of primary NS.[3] Llach report that the prevalence of RVT in nephrotic patients is 5–60%.[4] Kayali et al. reported deep venous thrombosis (DVT) to be the most common thrombotic complication in nephrotic patients.[5] In contrast, Suri et al. found PE to be more common than DVT.[6] In a prospective study by Li et al., 100 patients with MN were studied using CT pulmonary angiography and CT venography. VTE was demonstrated in 36% of the patients. Of these, 33% had RVT and 17% had PE.[7]

Available data are limited and conflicting and as such emphasizes the need for more prospective studies in this patient population.

Pathogenesis

The cause of the hypercoagulable state in patients with NS is not well-understood. In NS, damage to the glomerular membrane results in increased filtration of small proteins such as antithrombin III, plasminogen, protein C, and protein S, and this in turn leads to increased coagulability. In patients with NS, the loss of albumin and resultant hypoalbuminemia results in increased hepatic synthesis of fibrinogen which also favors formation of thrombus. The tendency of thrombus formation in the renal vein in NS may in part be due to the loss of fluid across the glomerulus. The resulting hemoconcentration in the postglomerular circulation may promote thrombus formation in patients who are already hypercoagulable.[1]

Location

Thromboembolism in NS can be venous or arterial; however, the incidence of arterial thrombosis is much lower compared to venous.[8] VTE in nephrotic patients involves DVT, PE, and RVT. Other less common sites of VTE, which are mostly reported in children include splenic vein, portal vein, cerebral venous sinuses, internal jugular vein, and vena cava. Arterial thrombosis, though less common, can be serious and life-threatening depending on the vessels involved. Involved arterial sites include aortic, renal, femoral, mesenteric, coronary, and cerebral arteries. The most common site of arterial thrombosis is the femoral artery, occurring mainly in children with NS.

Clinical predictors of thromboembolic risk in patients with nephrotic syndrome

Certain parameters have emerged as useful predictors in risk stratification of thrombotic events in patients with NS. These include histological diagnosis, biochemistry markers, and age.

Histologic diagnosis

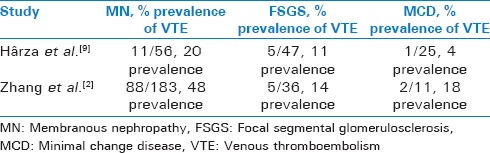

Definite diagnosis of NS is via biopsy, with histological diagnosis of MN conferring an increased risk of VTE. The mechanism by which MN is associated with increased risk of thromboembolism is poorly understood. Zhang et al. in a prospective analysis found MN present in 48% of nephrotic patients with PE.[2] Barbour et al. reported 1313 patients with idiopathic NS, and demonstrated a 2-fold increase in the risk of VTE in patients with MN [Table 1]. Table 2 shows an increased prevalence of VTE in patients with MN as compared to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and minimal change disease.[9]

Table 1.

Correlation of histological type of nephrotic syndrome with increased prevalence of venous thromboembolism

Table 2.

Incidence and prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with Nephritic syndrome

Biochemical markers

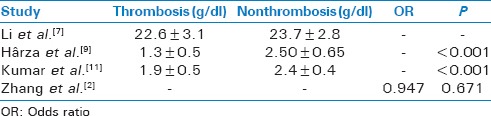

Reduced serum albumin is an independent risk factor for thrombotic events in patients with NS. Lionaki et al. studied 898 patients with biopsy proven MN and found that an albumin level <2.8 mg/dl was independently associated with a higher risk of thrombotic events,[10] and that every 1.0 mg/dl reduction in albumin was associated with a 2.13-fold increase in VTE. Nephrotic patients without MN experienced an increased risk of thrombosis as serum albumin fell below 2.0 mg/dl. Kumar et al. retrospectively studied 101 patients with MN. Patients with VTE had lower serum albumin concentrations (1.9 ± 0.5 g/dl) compared to patients without VTE (2.4 ± 0.4 g/dl).[11] Other predictors of increased risk of thrombosis in NS include high fibrinogen levels and low antithrombin levels [Table 3].[1]

Table 3.

Correlation of serum albumin with increased incidence of venous thromboembolism

Age

Age is an important risk factor for developing VTE. Nephrotic adults have approximately a 7–8 fold increase the incidence of thrombosis as compared to children. Zhang et al. demonstrated that age > 60 years old was an independent risk factor (P < 0.05) for VTE in nephrotic patients.[2]

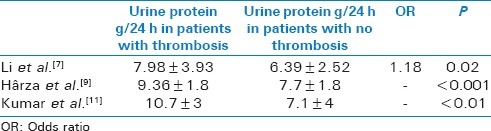

Urine protein excretion

High rates of protein excretion are associated with an increased incidence of thrombotic events in patients with NS. Kumar et al. retrospectively studied 101 patients with MN.[11] Patients with VTE had more proteinuria (10.7 g/dl/day) than patients without VTE (7.1 g/dl/day) [Table 4].[11]

Table 4.

Comparison of urine protein excretion (g/24 h) associated with venous thromboembolism in patients with nephrotic syndrome

Time from diagnosis

In a retrospective cohort study of 298 nephrotic patients by Mahmoodi et al., VTE developed within first 6 months in 9.85% of the patients. This compares to annual incidence rates of 1.02% over a 10-year follow-up period.[8]

Treatment

The aim of treatment in RVT is to reestablish renal function. Treatment includes treating the underlying etiology of NS, as well as anticoagulation, thrombolysis, and surgical thrombectomy. Anticoagulation is usually initiated with heparin and followed by warfarin using a target international normalized ratio of 2–3. The duration of anticoagulation varies, but most experts recommend treatment for at least a year and up to lifetime based on clinical response. If RVT is associated with PE, anticoagulation is recommended as long as the NS is present. Localized thrombolytic therapy can be used in patients with bilateral RVT and associated renal failure, large clot size with increased risk of embolization, and in patients who develop recurrent PE if there are no contraindications to thrombolysis. Surgical treatment of RVT is uncommon. It has however been used in patients with bilateral RVT, or when concomitant PE has occurred, and anticoagulation is contraindicated.[12] Reduction in proteinuria is also an important goal in the treatment of NS patients with RVT, and patients should be started on angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers.

Treatment of VTE in patients with NS is similar to that in patients without NS. Anticoagulation should begin as soon as possible using IV unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, or synthetic polysaccharides, followed by warfarin for at least 3–6 months or until the underlying illness has resolved or is in remission.[1] Patients with PE who have cardiovascular compromise and right ventricular dysfunction may require thrombolysis or embolectomy if thrombolysis is contraindicated.

Nephrotic patients with DVT, who are not candidates for anticoagulation should have a removable suprarenal inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placed, given the increased incidence of RVT in this patient population. Of course, IVC filters are not without complications. They have been associated with thrombosis and hematoma formation at the site of insertion, filter migration and embolization, and erosion through the IVC.

Prevention

There are limited data available regarding prevention of thrombosis in nephrotic patients. Prophylactic anticoagulation was studied by Lee et al.[13] Patients with MN were divided into three groups based on serum albumin concentration: Patients with serum albumin >2.5 mg/dl, serum albumin 2.0–2.5 mg/dl, and serum albumin <2.0 mg/dl. Bleeding risk was also estimated using the ATRIA score. Patients with a low risk of bleeding or a serum albumin <2.0 mg/dl benefited from prophylactic anticoagulation. In a retrospective analysis by Medjeral-Thomas et al.,[3] 143 patients with NS were followed after initiation of prophylactic anticoagulation. Patients with serum albumin <2.0 g/dl received prophylactic dose low molecular weight heparin or low-dose warfarin. Patients with albumin levels of 2–3 g/dl received aspirin 75 mg once daily. Over a 5-year period, no symptomatic VTE occurred in patients established on prophylaxis for at least 1 week, and only one patient was admitted urgently for gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

CONCLUSION

NS is a well-defined syndrome characterized by the presence of nephrotic range of proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperlipidemia. Although increased incidence of VTE is a well-reported complication associated with NS, the incidence, prevalence, risk factors, treatment options, and preventative strategies are not well-established. The increased propensity of thromboembolism in nephrotic patients is postulated to be a result of increased excretion of antithrombotic factors by the affected kidneys and increased production of pro-thrombotic factors by the liver. Most cases of VTE associated with NS reported in the literature have a preceding diagnosis of NS. We report a case of a young female presenting with dyspnea who was diagnosed to have PE. She was found to have NS and right RVT on further workup. NS should be considered in patients who present with VTE.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mirrakhimov AE, Ali AM, Barbaryan A, Prueksaritanond S, Hussain N. Primary nephrotic syndrome in adults as a risk factor for pulmonary embolism: An up-to-date review of the literature. Int J Nephrol. 2014;2014:916760. doi: 10.1155/2014/916760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang LJ, Zhang Z, Li SJ, Meinel FG, Nance JW, Jr, Zhou CS, et al. Pulmonary embolism and renal vein thrombosis in patients with nephrotic syndrome: Prospective evaluation of prevalence and risk factors with CT. Radiology. 2014;273:897–906. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medjeral-Thomas N, Ziaj S, Condon M, Galliford J, Levy J, Cairns T, et al. Retrospective analysis of a novel regimen for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:478–83. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07190713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llach F. Thromboembolic complications in nephrotic syndrome. Coagulation abnormalities, renal vein thrombosis, and other conditions. Postgrad Med. 1984;76:111. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1984.11698782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kayali F, Najjar R, Aswad F, Matta F, Stein PD. Venous thromboembolism in patients hospitalized with nephrotic syndrome. Am J Med. 2008;121:226–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suri D, Ahluwalia J, Saxena AK, Sodhi KS, Singh P, Mittal BR, et al. Thromboembolic complications in childhood nephrotic syndrome: A clinical profile. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2014;18:803–13. doi: 10.1007/s10157-013-0917-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li SJ, Guo JZ, Zuo K, Zhang J, Wu Y, Zhou CS, et al. Thromboembolic complications in membranous nephropathy patients with nephrotic syndrome-a prospective study. Thromb Res. 2012;130:501–5. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahmoodi BK, ten Kate MK, Waanders F, Veeger NJ, Brouwer JL, Vogt L, et al. High absolute risks and predictors of venous and arterial thromboembolic events in patients with nephrotic syndrome: Results from a large retrospective cohort study. Circulation. 2008;117:224–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hârza M, Ismail G, Mitroi G, Gherghiceanu M, Preda A, Mircescu G, et al. Histological diagnosis and risk of renal vein thrombosis, and other thrombotic complications in primitive nephrotic syndrome. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2013;54:555–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, Barbour S, Lee T, Hladunewich M, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:43–51. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04250511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S, Chapagain A, Nitsch D, Yaqoob MM. Proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia are risk factors for thromboembolic events in patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An observational study. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janda SP. Bilateral renal vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism secondary to membranous glomerulonephritis treated with percutaneous catheter thrombectomy and localized thrombolytic therapy. Indian J Nephrol. 2010;20:152–5. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.70848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Barbour SJ, Tannous S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2014;85:1412–20. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]