Abstract

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) has high mortality and necessitates prompt recognition of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) and initiation of plasmapheresis. We present a challenging diagnostic workup and management of a 42-year-old man who presented with anemia, thrombocytopenia, and schistocytes on peripheral smear, all pointing to MAHA. Plasmapheresis and steroid therapy were promptly initiated, but hemolysis continued. Further workup showed megaloblastic anemia, severe Vitamin B12 deficiency, high iron saturation, and absent reticulocytosis, none of which could be explained by TTP. Severe Vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to hemolytic anemia from the destruction of red cells in the marrow that have failed the process of maturation. However, this should not cause thrombotic microangiopathy. Previous reports of B12 deficiency presenting with MAHA and a TTP-like manifestation have identified acute hyperhomocysteinemia as a missing link between B12 deficiency and MAHA, so this possibility was further explored. Our patient similarly had significantly elevated serum homocysteine levels, confirming this suspicion of Vitamin B12 deficiency. Vitamin B12 replacement led to normalization of the elevated levels of homocysteine, the disappearance of schistocytes on the peripheral smear, and resolution of the microangiopathic hemolysis, thereby confirming the diagnosis. It is pertinent that intensivists not only know the importance of early recognition and treatment of TTP but are also familiar with rare conditions that can present in a similar fashion.

Keywords: Hyperhomocysteinemia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, peripheral smear, schistocytes, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

INTRODUCTION

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) should raise the possibility of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). While TTP is associated with high mortality and requires early recognition and initiation of therapy, ruling out other diagnoses is critical. We present a rare case of MAHA in the setting of severe Vitamin B12 deficiency, which presented as a diagnostic challenge.

CASE REPORT

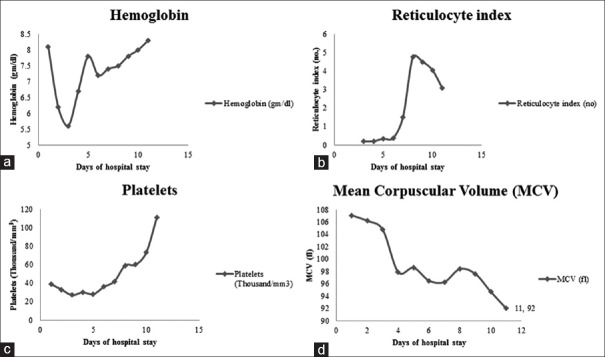

A 42-year-old African American diabetic male presented with complaints of presyncope and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). DKA resolved in 24 hours but laboratory workup revealed anemia and thrombocytopenia. He had noticed gradually increasing fatigue, with a weight loss of 6-8 pounds over 2 months. He reported smoking 2 packs of cigarettes per day and drinking 2-3 pints of vodka per day. One of his daughters reportedly had hemolytic anemia. Examination revealed significantly pale mucous membranes. There was no history of hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia. Laboratory evaluation on day 1 showed a white blood cell count of 4100 cells/mm3, hemoglobin (Hb) of 8.1 g/dL and a platelet count of 39,000 cells/mm3, compared to a year prior, when his Hb was 13.5 g/dL with a platelet count of 214,000/mm3. Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) was 107.1 µm3 and red cell distribution width was 19.0 (normal 11.7–15.2). His metabolic panel showed mildly elevated indirect bilirubin (1.6 mg/dL, normal 0.2–0.7 mg/dL). The anemia and thrombocytopenia with indirect hyperbilirubinemia pointed towards hemolysis. Peripheral smear [Figure 1] showed macrocytes, 3+ schistocytes, hypersegmented neutrophils, and very few platelets. Workup for anemia included a high serum iron (174 µg/dL; normal 50–180), low total iron binding capacity (199 µg/dL; normal 261–497), high percent iron saturation (87.4%; normal 20–55), normal ferritin (102 ng/mL, normal 17.9–464) and serum folate (17.9 ng/mL; normal 2.8–20), but severely decreased Vitamin B12 (159 pg/mL; normal 239–931), and normal thyroid function.

Figure 1.

Peripheral smear (day 1) demonstrating schistocytes (black arrows), hypersegmented neutrophils (blue arrows), macrocytes (red arrow), and very few platelets

The anemia, thrombocytopenia, and schistocytes pointed to MAHA which can be due to TTP, disseminated intravascular coagulation, malignant hypertension, preeclampsia, malfunctioning prosthetic valves, toxins or drugs. On day 2 of hospitalization, other laboratory data were revealed including lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) that was remarkably elevated at 5368 U/L and haptoglobin that was severely depressed at 5.83 mg/dL (normal 35–195 mg/dL) indicating significant ongoing hemolysis. Serum fibrinogen, fibrin-split products, d-dimer, and Coombs test were all normal, and the reticulocyte index was 0.3. Hb electrophoresis showed heterozygous HbC trait (50.8% HbA [normal 97.1–99.1] and 49.2% HbC), which usually does not cause hemolysis.

The presumptive clinical diagnosis was MAHA from TTP. Given the high morbidity and mortality rates associated with TTP, plasmapheresis was initiated after the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit on day 3 of his hospital stay.[1] Testing for ADAMTS-13 (A disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin-1 like domains) was performed. After 3 days of treatment, no response was observed, and prednisone (60 mg) was added. HIV, hepatitis profile, and blood cultures were negative. On day 4, the patient developed anaphylactoid reactions during plasmapheresis. Although plasmapheresis was initiated early for presumed TTP, the mild bilirubin elevation did not point in that direction as with a significantly elevated LDH and accompanying brisk hemolysis, concomitantly higher rise in bilirubin would be expected.

The lack of responsiveness to plasmapheresis and steroids signified that another diagnosis must be the etiology of MAHA, so plasmapheresis and steroids were discontinued on day 5.

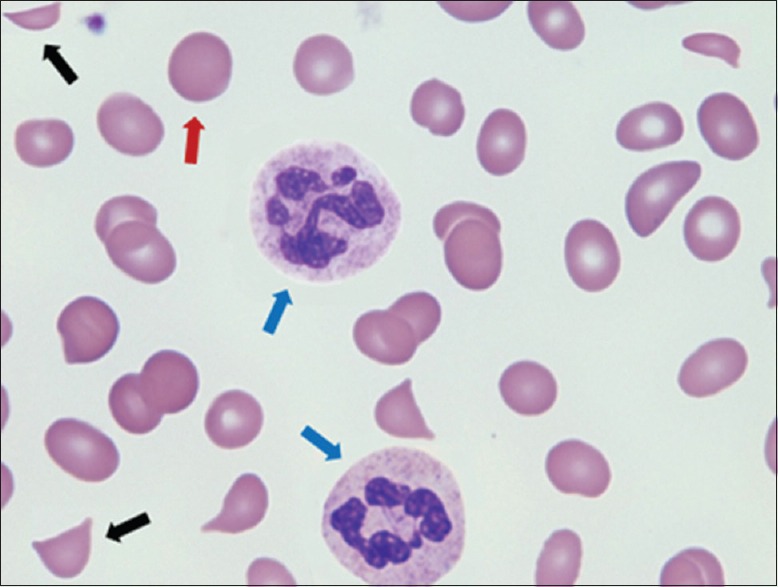

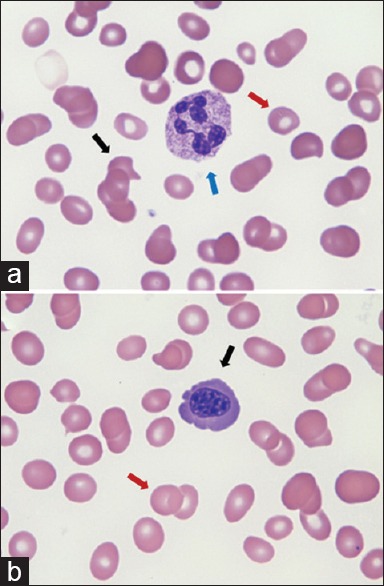

To tie together the Vitamin B12 deficiency and MAHA, a serum homocysteine level was significantly elevated at 88.3 µmol/L (normal < 15) but the ADAMTS-13 and methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTFR) mutations (C677T and A1298C) were negative. The elevated homocysteine level supported the diagnosis of the possible B12 deficiency-related MAHA. Parenteral replacement of Vitamin B12 resulted in a remarkable bone marrow response with a gradual increase in the Hb, reticulocyte index, and platelets [Figure 2a–c] and a corresponding decline in MCV [Figure 2d]. The schistocytes gradually disappeared on subsequent peripheral smears [Figure 3a] and nucleated red blood cells (RBCs) and teardrop cells and platelets appeared, which indicated improved marrow function [Figure 3b]; the hypersegmented neutrophils continued to be seen for about 3-4 weeks. The patient started feeling much better and regained a good appetite.

Figure 2.

Improvement in hemoglobin (a), and reticulocyte index (b), platelet count (c) with a decrease in mean corpuscular volume (d) with Vitamin B12 replacement

Figure 3.

Peripheral smear on day 8 (a) showing macrocytes (red arrow), hypersegmented neutrophils (blue arrow) and teardrop cells (black arrow) (b) macrocytes with decreased mean corpuscular volume (red arrow) and nucleated red blood cell (black arrow)

DISCUSSION

The larger clinical question which made this case interesting was whether TTP was the real diagnosis, and whether Occam's razor could be applied to correlate the MAHA and Vitamin B12 deficiency. Lack of Vitamin B12 halts maturation of all cell lines in the marrow and can present with hemolytic anemia due to ineffective erythropoiesis and indirect hyperbilirubinemia, but does not usually present with MAHA. Microangiopathy or fragmentation hemolysis requires intravascular hemolysis of RBC from mechanical trauma or sheer stress. A literature search revealed very few cases of patients with Vitamin B12 deficiency presenting with MAHA, termed as pseudothrombotic angiopathy.[2,3,4,5] Others have suggested that severe hyperhomocysteinemia with B12 deficiency leads to a very interesting peripheral smear and a clinical picture resembling TTP.[6,7] One of two common mutations (C677T and A1298C) in MTFR, an enzyme involved in the remethylation reaction of homocysteine, was present in patients who presented with MAHA in the setting of B12 deficiency.[6]

Hemolytic anemia due to Vitamin B12 deficiency leads to indirect hyperbilirubinemia (from the destruction of red cells in the marrow that have failed the process of maturation) or extravascular hemolysis, which should not cause microangiopathy. As mentioned above, only rarely do B12-deficient patients present with a rare picture of schistocytes on the peripheral smear or MAHA (labeled as pseudothrombotic angiopathy or Moshkowitz syndrome),[2,3,4,5] which has been postulated to arise from acute hyperhomocysteinemia.[6,7] Importantly, patients in these reports tested positive for mutations in MTFR, an enzyme involved in the remethylation reaction converting homocysteine to methionine. Acute hyperhomocysteinemia is precipitated by the concurrent inhibition of MTFR by the mutation as well as deficiency of B12 or folic acid. Vitamin B12 replacement in these patients led to normalization of the elevated levels of homocysteine and the peripheral smear.[6,7]

It is possible that MAHA from acute hyperhomocysteinemia in B12 deficiency also depends on the susceptibility of RBC to hemolysis. The patient in this report had major elevation of homocysteine in the absence of MTFR mutations. However, the presence of HbC trait, as well as hyperglycemia from DKA, could potentiate the hemolytic process that leads to MAHA. The fact that treatment with Vitamin B12 normalized blood counts and homocysteine levels lends support to the observation of hyperhomocysteinemia causing MAHA in our B12 deficient patient. We hence report a very rare presentation of MAHA in the setting of B12 deficiency but in the absence of MTFR mutation in a patient with HbC trait and DKA. This report should remind intensivists to broaden their differential diagnoses when Vitamin B12 deficiency is evident in patients with microangiopathic hemolysis, or in patients who are not responsive to traditional therapies for TTP.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the efforts of Drs. Alan Kerr, Stephen Slone and Alireza Abdolmohammadi in the management of this patient and Ms. Clare Prendergast in the review of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.George JN. Clinical practice. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1927–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp053024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrès E, Affenberger S, Zimmer J, Vinzio S, Grosu D, Pistol G, et al. Current hematological findings in cobalamin deficiency. A study of 201 consecutive patients with documented cobalamin deficiency. Clin Lab Haematol. 2006;28:50–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.2006.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrès E, Affenberger S, Federici L, Korganow AS. Pseudo-thrombotic microangiopathy related to cobalamin deficiency. Am J Med. 2006;119:e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tadakamalla AK, Talluri SK, Besur S. Pseudo-thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: A rare presentation of pernicious anemia. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3:472–4. doi: 10.4297/najms.2011.3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noël N, Maigné G, Tertian G, Anguel N, Monnet X, Michot JM, et al. Hemolysis and schistocytosis in the emergency department: Consider pseudothrombotic microangiopathy related to Vitamin B12 deficiency. QJM. 2013;106:1017–22. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hct142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acharya U, Gau JT, Horvath W, Ventura P, Hsueh CT, Carlsen W. Hemolysis and hyperhomocysteinemia caused by cobalamin deficiency: Three case reports and review of the literature. J Hematol Oncol. 2008;1:26. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-1-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapuis TM, Favrat B, Bodenmann P. Cobalamin deficiency resulting in a rare haematological disorder: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:80. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]