Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To describe nutrient intake in critically ill children, identify risk factors associated with avoidable interruptions to enteral nutrition (EN) and to highlight opportunities to improve enteral nutrient delivery in a busy tertiary pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

DESIGN, SETTING AND MEASUREMENTS

Daily nutrient intake and factors responsible for avoidable interruptions to EN were recorded in patients admitted to a 29-bed medical and surgical PICU over a period of 4 weeks. Clinical characteristics, time to reach caloric goal and parenteral nutrition (PN) use were compared between patients with and without avoidable interruptions to EN. Logistic regression was used to determine predictors of avoidable EN interruptions.

MAIN RESULTS

Daily record of nutrient intake was obtained in 117 consecutive patients (median age 7yrs). Eighty (68%) patients received EN (20% post-pyloric) for a total of 381 EN days (median 2 days; IQR 1.0 – 6.5 days). Median time to EN initiation was less than 1 day (Inter-quartile range 0.0 – 3.5). However, EN was subsequently interrupted in 24 (30%) patients at an average of 3.7 ± 3.1 times per patient (range 1 – 13), for a total of 88 episodes accounting for 1483 hours of EN deprivation in this cohort. 51/88 (58%) episodes of EN interruptions were deemed as avoidable in 15/80 patients. Reasons for avoidable EN interruptions included; a) endotracheal tube extubation or intubation, b) intolerance to EN, c) mechanical issues related to post-pyloric feeding tubes and d) other procedures in the operating room, radiology suite or at the bedside.

Patients with avoidable EN interruptions were younger, more likely to have post-pyloric feeds (60% vs. 11%, p=0.0001) and required mechanical ventilatory support (93% vs. 46%, p=0.0001). PN use was more than tripled and time to reaching caloric goal was significantly delayed in patients with avoidable EN interruptions. Multivariate modeling identified length of EN therapy and need for mechanical ventilation as the most significant independent predictors of EN interruption.

CONCLUSIONS

EN interruptions during critical illness is associated with increased reliance on PN and impairs ability to reach caloric goal in children admitted to the PICU. EN is frequently interrupted for avoidable reasons in critically ill children. Knowledge of existing barriers to EN, such as those identified in our study, will allow appropriate interventions to be planned. Such interventions targeted at patients at a high risk of EN interruptions may optimize enteral feeding with a potential for improved caloric intake and decreased reliance on PN.

Keywords: Enteral nutrition, barriers, PICU, critical care, parenteral nutrition

INTRODUCTION

The prescription of optimal nutrition support therapy during critical illness requires an individualized assessment of the risks and benefits associated with the timing, route and quantity of nutrient intake. Enteral nutrition (EN) is the preferred mode of nutrient intake in critically ill patients with a functional gastrointestinal system, due to its lower cost and complication rate when compared to parenteral nutrition (PN) 1. Early institution of EN is associated with beneficial outcomes in animal models and human studies 2, 3, and has been increasingly implemented during critical illness, often using nutritional guidelines or protocols 4, 5. However, subsequent maintenance of enteral nutrient delivery remains elusive as EN is frequently interrupted in the intensive care setting for a variety of reasons, some of which are avoidable 6, 7. Frequent interruptions in enteral nutrient delivery may affect clinical outcomes secondary to suboptimal provision of calories and reliance on PN 6. In order to realize the potential benefits of EN in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), both early initiation and maintenance of enteral feeds must be assured.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to identify risk factors associated with avoidable interruptions to EN in critically ill children admitted to a busy multidisciplinary PICU. We aimed to evaluate the frequency of avoidable EN interruptions, their impact on nutrient delivery and to identify those children who are at a risk for such interruptions during critical illness. We hypothesized that EN is frequently interrupted following initiation, and that a significant proportion of these interruptions are avoidable. Identification of high-risk subjects will allow educational interventions and practice modifications to be targeted with the aim to decrease the incidence of avoidable EN interruptions in the PICU.

DESIGN, SETTING AND MEASUREMENTS

After obtaining approval from the institutional review board, we conducted a prospective, bedside evaluation of daily nutrition practice in a 29-bed medical and surgical PICU at Children's Hospital Boston. Patients with a PICU length of stay of 24 hours or longer were eligible for data collection. Patients with PICU length of stay under 24 hours, on end-of-life compassionate care or those who were transferred from another intensive care facility were excluded from this study. In this non-intervention study, parenteral and enteral nutrient intakes were recorded daily by bedside nursing staff for all consecutive eligible patients, admitted over a period of 4 weeks. Enteral nutrient intake data were recorded for patients receiving EN for 24 hours or more. Participating staff members reviewed the objectives of the study and were trained to complete the data collection tool prior to initiating the study. We utilized group discussions, information leaflets and electronic dissemination of information during this training period. We also provided daily reminders to review and complete daily bedside recording and 24-hour access to the investigators in order to facilitate the completion of nutrition procedures at the bedside. The study was conducted by a multidisciplinary group of investigators, including an intensivist, nursing staff, nutritionist, gastroenterologist and biostatistician.

Institutional enteral and parenteral nutrition guidelines

Nutritional therapy was provided according to existing institutional guidelines. EN is preferred as the mode of nutrition support in our PICU. Patients admitted to our PICU are started on EN support as soon as possible after PICU admission. Patients with hemodynamic instability requiring escalating vasoactive medication support, significant upper gastrointestinal bleeding, presence or high risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, postoperative ileus, intestinal obstruction and those with graft versus host disease following allogenic stem cell transplantation are not offered early EN. Enteral feeding is held for 6 hours prior to elective anesthesia for general surgery or sedation for procedures, and it is held for 4 hours prior to elective endotracheal intubation and extubation. The route of EN is determined on an individual basis. Oral feeds are preferred in unintubated patients who are alert with optimal cough and gag reflexes. In intubated patients, gastric feeds are provided, usually as intermittent boluses, unless concerns for the risk of aspiration are high; in which case continuous post-pyloric feeding is administered. The type of formula for EN is selected by the dietician, based on age, medical history and nutritional assessment. The formula volumes and caloric goals are calculated for each patient and a plan for EN initiation and advancement is prescribed. Following any interruption, other than those for feed intolerance, feeds are restarted according to previously established feeding schedules and advanced as tolerated. PN is indicated when fasting (on minimal or no EN) is anticipated for 5 days or more 8. In cases of malnutrition, low birth weight or hypermetabolism, PN is initiated if fasting is anticipated for 3 days or more.

Nutritional data collection

In patients who received at least 24 hours of EN during their PICU stay, we recorded the time of initiation of enteral intake, the route of enteral feeding, intolerance to EN and any interruption to enteral nutrient intake. EN interruption was defined as an episode of stoppage of EN for a period longer than 30 minutes, in a patient in whom EN has been previously initiated. Causes of EN interruption were categorized a priori into the following broad groups: a) endotracheal intubation or extubation, b) diagnostic tests or procedures in the radiology suite, c) other procedures at the bedside, d) surgical procedure in the operating room, e) feeding intolerance (as determined by the healthcare team at the bedside), f) feeding tube malfunction, malposition or obstruction, and g) other reasons not already specified. The reason(s) for interruption and the time of restarting EN were recorded for each episode.

All episodes of interruptions to EN delivery were examined and avoidable episodes were identified by consensus among the multidisciplinary group of investigators. An episode of EN interruption was deemed avoidable if the reason or duration of interruption was not in accordance with the institutional nutrition support guidelines described earlier. Nurses documented the nutritional record at least twice daily. Data were examined to allow the capture of any missing elements at the end of each nursing shift. The accuracy of the nutritional record was verified by a dedicated dietician on the unit at regular intervals and also crosschecked with the existing electronic medical record. Data related to outcomes such as duration of mechanical ventilation support, length of PICU stay and timing of achievement of caloric goal were abstracted retrospectively from patient charts following completion of enrollment and after the patient was discharged from the PICU.

Statistical analysis

Distributions of all variables were examined for outliers or missing data and corrected upon chart review whenever possible. Patient characteristics were described using frequency tables if categorical and measures of central tendency and spread otherwise. Variables that were reasonably normally distributed were described using mean (standard deviation, SD), while those displaying a high degree of skew were characterized by their median and inter-quartile range (IQR). Comparisons in patient characteristics were made between those receiving and not receiving EN. In patients who received EN for at least 24 hours, clinical characteristics were compared between those with and without interruptions to enteral feeding. Tests of significance for two-group comparisons included Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, and Student's t-test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for normal and skewed distributions, respectively.

Logistic regression was used to determine predictors of all EN interruptions as well as predictors of avoidable EN interruptions among patients who received EN 9. Model selection proceeded by examining unadjusted results and then subsets of predictors until a parsimonious model was found based upon clinical judgment and likelihood ratio tests. Estimates of coefficients and 95% Wald confidence intervals were expressed as odds ratios. The ability of the regression model to correctly predict interruption of EN was quantified by the c statistic associated with the area under the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve. For number of days of EN, an optimal cut-point on the ROC curve was selected at which point the discriminatory power of the regression model for this predictor was maximized. Tests of significance were 2-sided, and all statistical analysis was conducted with SAS/STAT software, Version 9.1 of the SAS System for Windows.

MAIN RESULTS

A total of 117 patients admitted during the 4-week enrollment period were included in this study. Critical care nurses obtained a detailed daily record of nutrition practice at the bedside during 1020 nursing shifts over 4 weeks. Clinical characteristics of this cohort are described in Table 1. Patients ranged in age at the time of admission from newborn to 36 years, with 20 (17%) patients being under the age of 1 year. Both genders were equally represented. Total PICU length of stay of the patients enrolled in this study ranged from 1 – 246 days, with a median of 2 days. Eighty (68%) patients received EN for at least 24 hours during their PICU course, accounting for a total of 381 EN days (median duration 2 days; IQR 1.0 – 6.5 days). Among patients receiving EN, median duration from PICU admission to EN initiation was 1 day (IQR 0.0 – 3.5) with 75% of patients on EN by the end of Day 3. Twenty percent (16/80) of the patients received EN via the post-pyloric route. The rest received feeds either orally, via gastric tube or through a gastrostomy tube.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of the cohort

| Characteristic | All Patients* | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at PICU admission (years) | 7.2 (1.7 – 15.3) | |

| Age <1 yr | 20 (17%) | |

| Female gender | 60 (51%) | |

| PRISM 3 score (116 patients) | 3.0 (0.0 – 5.0) | |

| PICU length of stay (days) | 2.0 (1.0 – 8.0) | |

| Patients admitted to the medical service | 59 (50%) | |

| Respiratory failure | 24 | |

| Seizures | 8 | |

| Shock | 4 | |

| Oncology / Bone Marrow Transplant | 7 | |

| Bronchiolitis | 3 | |

| Reactive airway disease | 2 | |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 1 | |

| Anaphylaxis | 1 | |

| Interventional radiology procedures | 3 | |

| Patients admitted to the surgical service | 63 (54%) | |

| Neurosurgery | 21 | |

| General surgery (Laparotomy) | 13 | |

| Mediastinal surgery | 2 | |

| Trauma | 2 | |

| Plastic surgery | 3 | |

| Oral and maxillofacial surgery | 4 | |

| Orthopedic procedures | 3 | |

| Renal transplant | 4 | |

| Otolaryngology surgery | 5 | |

| Patients on EN for at least 24 hours | 80 (68%) | |

| Days on EN (80 patients) | 2.0 (1.0 –6.5) | |

| % PICU days on EN (80 patients) | 77 (41 – 100) | |

| Days from PICU admission to starting EN (80 patients) | 1.0 (0.0 – 3.5) | |

| Caloric goal reached during PICU course (80 patients on EN) | 49 (61%) | |

| Days from PICU admission to reach caloric goal (49 patients) | 4.0 (1.0 – 8.0) | |

| Mechanical ventilation support during PICU course | 60 (51%) | |

| Patients on any PN during PICU course | 15 (13%) | |

| Days on PN (15 patients) | 6.0 (3.0 – 10.0) | |

| % PICU days on PN (15 patients) | 41 (25 – 75) | |

| Charge of PN per patient in U.S. dollars (15 patients) | 987.00 (493.50 – 1645.00) | |

PICU (Pediatric Intensive Care Unit), PRISM (...), EN (enteral nutrition)

N=117 unless otherwise noted.

Data presented as median (IQR) or n (%).

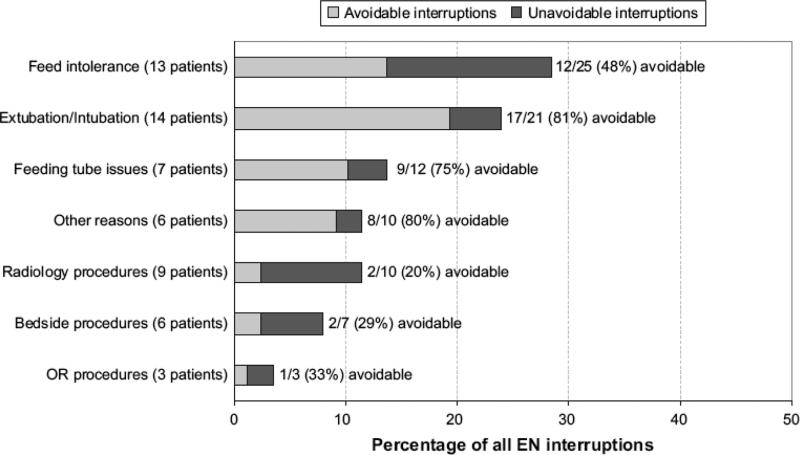

Following initiation, EN was interrupted in 24 (30%) patients at an average of 3.7 ± 3.1 times per patient (range 1 – 13), for a total of 88 episodes accounting for 1483 hours of EN deprivation. Fifty-one (58%) episodes of EN interruptions in 15 patients in our study were deemed as avoidable (Figure 1). The characteristics of patients with avoidable interruptions have been described in Table 2. Feeds were stopped for a variety of reasons including; a) fasting for extubation or intubation, b) intolerance to EN for gastric residuals, abdominal discomfort or distension, c) mechanical problems with post-pyloric feeding tubes, d) procedures in the operating room, radiology suite or at the bedside. Figure 1 shows the proportion of episodes that were avoidable in each of these categories.

Figure 1.

Reasons for interruptions to Enteral Nutrition (EN)

TABLE 2.

[A] Comparison of patients with any EN interruption versus those without EN interruption, and [B] Comparison between patients with avoidable EN interruptions vs. those without voidable EN interruptions

| [A] EN Interruption (all) * | [B] EN Interruption (avoidable)* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No (n=56) | Yes (n=24) | P-value* | No (n=65) | Yes (n=15) | P-value* |

| Age at PICU admission in years | 9.5 (2.2 – 15.3) | 1.4 (0.8 – 8.5) | 0.006 | 8.3 (2.1 – 15.2) | 1.0 (0.5 – 10.2) | 0.02 |

| Age < 1 year | 5 (9%) | 10 (42%) | 0.001 | 8 (12%) | 7 (47%) | 0.006 |

| Female gender | 24 (43%) | 16 (67%) | 0.09 | 30 (46%) | 10 (67%) | 0.25 |

| PRISM 3 score | 2.5 (0.0 – 4.0) | 3.0 (1.0 – 7.0) | 0.13 | 2.0 (0.0 – 4.0) | 3.0 (1.0 – 7.0) | 0.08 |

| Percent PRISM predicted mortality | 0.53 (0.23 – 1.11) | 1.00 (0.76 – 2.49) | 0.008 | 0.60 (0.31 – 1.21) | 1.00 (0.53 – 2.75) | 0.13 |

| PICU length of stay in days | 2.0 (1.0 – 4.0) | 18.0 (7.5 – 30.5) | <0.0001 | 2.0 (1.0 – 6.0) | 23.0 (11.0 – 69) | <0.0001 |

| Days from PICU admission to start EN | 1.0 (0.0 – 2.5) | 4.0 (2.0 – 6.5) | <0.0001 | 1.0 (0.0 – 3.0) | 5.0 (2.0 – 8.0) | 0.003 |

| EN duration in days | 1.0 (1.0 – 2.0) | 11.0 (5.0 – 16.5) | <0.0001 | 1.0 (1.0 – 3.0) | 15.0 (8.0 – 17.0) | <0.0001 |

| % PICU days given EN | 100 (50 – 100) | 57 (33 – 81) | 0.007 | 90 (46 – 100) | 58 (25 – 78) | 0.03 |

| Post-pyloric feeds | 3 (5%) | 13 (54%) | <0.0001 | 7 (11%) | 9 (60%) | 0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 21 (38%) | 23 (96%) | <0.0001 | 30 (46%) | 14 (93%) | 0.001 |

| Surgery | 28 (50%) | 10 (42%) | 0.63 | 30 (46%) | 8 (53%) | 0.78 |

| PN administered | 6 (11%) | 7 (29%) | 0.05 | 7 (11%) | 6 (40%) | 0.01 |

| PN days | 5.0 (2.0 – 7.0) | 7.0 (5.0 – 12.0) | 0.40 | 7.0 (2.0 – 7.0) | 8.0 (5.0 – 12.0) | 0.49 |

| PN charge ($) | 822.50 (329.00 – 1151.50) | 1151.50 (822.50 – 1974.00) | 0.40 | 1151.50 (329.00 – 1151.50) | 1316.00 (822.50 – 1974.00) | 0.49 |

| Caloric goal reached | 28 (50%) | 21 (88%) | 0.002 | 35 (54%) | 14 (93%) | 0.007 |

| Time to reaching caloric goal in days | 1.0 (1.0 – 4.0) | 7.0 (4.0 – 11.0) | 0.0004 | 2.0 (1.0 – 6.0) | 8.0 (5.0 – 11.0) | 0.002 |

PICU (Pediatric Intensive Care Unit), PRISM (...), EN (enteral nutrition)

Data presented as median (inter-quartile range or n (%).

P-value from Fisher exact test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Thirty-seven (32%) patients in our study did not receive any EN during their PICU course. There were no significant differences between patients in this group vs. those in the EN group, except for a much shorter PICU length of stay. The median PICU length of stay for patients who did not receive any EN was 1 day (IQR 1.0 – 2.0), compared to 4 days (IQR 1.0 – 10.5) in patients who received some EN (P<0.0001). Length of PICU stay was less than 3 days in 31/37 (84%) patients who did not receive EN. PN was used in 3/37 (8%) patients in the group deprived of any EN, accounting for a total of 12 PN days. Twenty-four (65%) patients who did not receive EN were on the surgical service including 6 patients who underwent thoraco-abdominal surgeries. Postoperative ileus and hemodynamic instability were the commonest reasons for withholding EN in this group. Mechanical ventilatory support was required for 10/37 patients (including 3 patients on non-invasive respiratory support).

Table 2 shows unadjusted comparisons in patients who received EN; [A] between patients with at least one EN interruption and the rest, and [B] between patients who had at least one avoidable EN interruptions and the rest. Patients with episodes of avoidable EN interruptions were younger (47% under the age of 1 year compared with 12%, p=0.006); more likely to have post-pyloric feeds (60% vs. 11%, p=0.0001) and had a higher likelihood of requiring mechanical ventilation (93% vs. 54%), p=0.001). Patients with longer PICU stay, delayed initiation of EN and increased EN exposure were more likely to have interruptions (p<0.01 for each). Furthermore, patients with avoidable EN interruptions had more than 3 times higher likelihood of PN use and required a significantly longer period to reach their prescribed caloric goal.

In patients with any EN interruption (avoidable and unavoidable), multivariable logistic regression showed that each additional day of EN was associated with increased odds of EN interruption of 1.43 (95% CI 1.18 – 1.72). In addition, the odds of EN interruption were 20 times higher among patients with mechanical ventilation than those without, independent of the length of exposure to EN (95% CI 1.35 – 310.45). No other variables were associated with EN interruption after adjusting for these two covariates. Although patients with EN interruptions were associated with longer duration of EN and PICU length of stay, the severity of illness at admission was not significantly higher in this group compared to those without EN interruptions. The ROC curve generated by the multivariate regression model showed a threshold for EN duration as 4 days, with maximized true positivity (83%) and minimized false positivity (13%). This threshold indicates that 83% of the time patients with 4 or more days of EN were correctly classified as experiencing interruptions to EN, while those with three or fewer days of EN were correctly classified as not experiencing EN interruptions.

In patients with only avoidable EN interruptions, multivariable logistic regression analysis of data showed that each additional day of EN was associated with increased odds of an avoidable EN interruption of 1.39 (95% CI 1.20 – 1.60). No other variables were associated with EN interruption after adjusting for days of EN.

DISCUSSION

Although EN is the preferred mode of nutrient delivery in critically ill subjects, barriers to optimal delivery of enteral nutrients at the bedside persist 10. The care of a critically ill patient involves multiple interventions, which often compete with the delivery of EN in the intensive care setting. Elective procedures, unplanned interventions or diagnostic tests often require a fasted state requiring interruption of EN. In addition, feed intolerance or contraindications to enteral feeding related to the disease processes may require feeds to be held or discontinued in the PICU. However, a significant number of eligible patients are deprived of EN during critical illness due to avoidable factors, such as, suboptimal prescription, failure to initiate EN early or frequent and prolonged interruptions to enteral feeding 6, 7, 11. Delayed initiation and subsequent interruptions contribute to suboptimal EN administration in the PICU.

A majority of the patients who received EN in our study were started on enteral nutrients early in their PICU course. Patients who did not receive EN included those who had a short stay in the PICU or in whom EN was contraindicated (following major thoraco-abdominal surgery with ileus or in cases with hemodynamic instability). This was in accordance with our existing nutrition support guidelines. Despite the successful institution of early EN in most patients in this study, we recorded a high rate of subsequent EN interruptions. It is indeed remarkable that more than half of all episodes of EN interruptions in our study were deemed avoidable (Figure 1), either due to unacceptably long duration of fasting or unclear reason for feed interruption. These observations provide opportunities for anticipatory education of healthcare workers and vigilance to prevent episodes of unnecessary fasting.

Frequent or prolonged interruptions to EN during critical illness may result in either suboptimal delivery of macronutrients and failure to achieve caloric goal or reliance on PN. Patients with avoidable EN interruptions in our study required significantly longer periods to reach the prescribed caloric goal and were more than three times more likely to be started on PN. Increased reliance on PN during critical illness may expose the patient to the higher cost, infectious risks and other morbidities associated with PN 17. The use of PN to supplement suboptimal EN in select patients with unavoidable EN interruptions may be reasonable. Of the 6 patients without EN interruptions who received PN, 4 had delayed EN initiation, 2 were unable to advance EN to goal and were supplemented with PN. Achievement of caloric goal is another relevant outcome in critically ill children. Failure to meet caloric goals due to suboptimal nutrient delivery has been previously reported in critically ill children 6, 12-14. The commonest reasons for suboptimal enteral nutrient intake in these studies were fluid restriction, procedural feed interruptions and feed intolerance. Consistently underachieved nutrition goals due to hindered enteral nutrient intake may impact patient outcomes 14-16. Failure to meet energy goals was associated with significant weight loss during the PICU course in critically ill infants following cardiac surgery 6. Identifying patients at high risk of EN deprivation will allow targeted interventions aimed at optimizing EN delivery during critical illness.

The characteristics of patients with unavoidable and avoidable EN interruptions in our study have highlighted important risk factors for EN deprivation in the PICU. Patients with EN interruptions were younger, more likely to require mechanical ventilatory support, had a delayed initiation of their EN and were more likely to be fed via the post-pyloric route. In addition, they had significantly longer duration of stay in the PICU as well as higher number of days of EN intake. Longer PICU stay may increase the exposure to EN, which may then increase the likelihood of interruptions to EN. After adjusting for the length of PICU stay, we identified EN duration and the need for mechanical ventilation as the most significant risk factor associated with EN interruptions. Patients exposed to EN for 4 days or longer were particularly associated with the risk of EN interruptions in our analysis. The reason for this threshold is unclear but it may be clinically relevant for targeting patients for educational efforts and anticipatory interventions aimed at reducing the likelihood of feed interruptions. Critically ill children requiring mechanical ventilation and with an anticipated need for EN longer than 4 days would be the population of interest for future studies on EN delivery. Patients with avoidable interruptions had similar characteristics with a significantly higher PN use and failure as well as delay in reaching caloric goal. Despite longer PICU stay, patients with avoidable EN interruptions did not have significantly higher illness severity scores on admission. Furthermore, the proportion of their PICU stay that they received EN was actually lesser than the rest of the patients. Thus, the longer PICU stay in patients with EN interruption was neither related to illness severity on admission, nor was it associated with increased EN exposure. PICU length of stay is an important outcome of critical illness and its relationship with suboptimal EN delivery needs to be further examined in future studies.

Many of the problems with EN in critically ill children reported in our study have been described in the adult critical care population nearly a decade ago 11. Persistence of some of these avoidable deficiencies in EN provision during critical illness is regrettable, especially as the enthusiasm for EN has grown over the years. The episodes of avoidable EN interruptions in our study need careful examination in order to identify the barriers and plan interventions to prevent or minimize EN deprivation around these events. These episodes included longer periods of fasting for procedures that were either scheduled in the morning (after overnight fasting), time of procedure not specified or where procedures/diagnostic tests were rescheduled or canceled. Careful consideration of procedure times, communication between team members and strict adherence to hospital policies for fasting times prior to procedures would prevent several hours of unnecessary fasting in PICU patients.

Intolerance to enteral feeding was the most frequently reported reason for stopping EN delivery in our cohort. We observed a high degree of variability among the healthcare team in dealing with this problem. Increased abdominal girth, high gastric residual volumes (GRV), abdominal discomfort and diarrhea were some of the criteria used by healthcare workers to diagnose enteral feeding intolerance. GRV is frequently used as a surrogate for delayed gastric emptying. However, its correlation with the risk of aspiration in critically ill children is debatable and the lower limit of GRV that protects from risk of aspiration is not known 18, 19. In the absence of severely delayed gastric emptying, computer modeling has shown that GRV plateaus at under 900ml in critically ill adults 20 . Furthermore, studies have shown poor correlation of GRV with clinical and radiographic examination and questioned the precision of measured GRV in predicting gastric emptying 21. Thus, the value of GRV monitoring in enterally fed critically ill children is doubtful and may pose as a barrier to EN provision. The routine use of GRV measurement as a guide to enteral feeding or as a marker of risk of aspiration is questionable 22, 23. Future studies, which clarify the relevance of GRV in the pediatric population, will instruct practical guidelines and allow uniform management at the bedside. Other tests to detect delayed gastric emptying, dysmotility or aspiration have had limited success. There is an urgent need to develop safe, reliable and efficacious diagnostic tests to detect aspiration and gastric emptying in children. PN may have a role in children with true EN intolerance or in children with unavoidable EN interruptions. In these cases, PN may substitute or supplement EN to achieve nutrient intake goals.

Endotracheal tube related procedures were the second most common reason for EN interruptions in our study. A majority of the episodes of pre-intubation or pre-extubation EN interruptions exceeded our recommended institutional guidelines for fasting periods around these procedures. Feeding tubes were often removed at the time of extubation, necessitating replacement in many of these patients. In some cases where planned extubation was rescheduled, feeds continued to be held for over 24 hours until the actual procedure. Guidelines for prudent duration of fasting for gastric and post-pyloric fed patients around these episodes would help prevent unnecessarily prolonged feed interruption. In patients fed via the post-pyloric route and awaiting extubation, there might be a case for smaller periods of fasting or even continuing post-pyloric EN, with no increase in the in rate of aspiration, vomiting, diarrhea or abdominal distension 24.

Post-pyloric route was used in 20% of patients on EN, and in a majority of patients with EN interruptions in our study. In a randomized trial comparing gastric vs. post-pyloric feeds in 74 critically ill children, there were no differences in microaspiration, tube displacement and feed intolerance between the 2 groups, but a higher percentage of subjects in the post-pyloric group achieved their daily caloric goal, compared to the gastric fed group. Improved feed tolerance and decreased incidence of abdominal distension has been reported in critically ill children receiving early (less than 24 hours after PICU admission) vs. late post-pyloric feeds 25. Despite the lack of strong evidence to support the use of one route of feeding over the other, the post-pyloric route has been successfully used for nutritional support of the critically ill child 5, 26, 27. The post-pyloric route may be a reasonable option for patients not able to tolerate gastric feeds and may reduce the rate of complications and costs associated with the use of PN in this subgroup of patients 28. However, the post-pyloric administration of nutrients may be limited by availability of local expertise in the placement of transpyloric feeding tubes. A dedicated team of trained nurses provides bedside support for the placement and trouble shooting of transpyloric tubes on our unit. Despite the on-site interventional radiology support and experience with the bedside placement of post-pyloric feeding tubes; tube malposition, obstruction and placement failure were some of the mechanical issues responsible for EN interruptions in 43% of patients who received post-pyloric feeding. Failure to address mechanical tube issues within 2 hours was recorded in 9 of the 12 episodes of EN interruption in these patients. The incidence of EN interruptions due to such mechanical issues may offset the perceived benefits of post-pyloric feeding 29.

Our study has a number of limitations. We have reported a single center experience with EN and identified risk factors that were associated with a high risk of EN failure in critically ill children in our PICU. It is likely that individual centers may have problems with EN delivery that are unique to their institution. Enteral nutrient delivery is widely variable between units with a significant disparity between prescribed and delivered enteral volumes in critically ill adults 7. However, the main results of our study are generalizable to any medium or larger sized PICU. The study did not involve any interventions and bedside nurses recorded the data. The investigators did not participate in providing care to the patients enrolled in this study and hence the observations are unlikely to be biased. We do not routinely measure resting energy expenditure in all PICU patients, hence estimated caloric and volume goals were used to prescribe caloric or volume intake. We did not measure the protein intake and excretion in our subjects and hence cannot comment on the effect of EN deprivations on protein balance. With the use of standard age-based formulae, the caloric and protein content of diet are likely to correlate with the volume administered. Future studies could examine the effect of suboptimal EN on caloric and protein balance, gastrointestinal mucosal function, change in anthropometric parameters after their discharge and other relevant outcomes. Our study was not powered to detect outcomes such as infectious complications, long-term morbidity or mortality. However, our observations related to the inability or delays in achieving caloric goal and increased PN use in patients with interrupted EN are interesting. These observations will need to be repeated in a multicenter study to examine the true impact of suboptimal EN on clinical outcomes in the PICU population. A targeted intervention aimed at patients who are at a high-risk of EN interruptions is the next step towards achieving the perceived benefits of optimal EN during critical illness and its impact on long-term outcomes.

In conclusion, despite early initiation of EN, feeds were interrupted in many critically ill children admitted to our busy medical and surgical PICU. Avoidable EN interruptions were associated with more than 3-fold increase in the use of PN and significant delay in reaching caloric goals. This collaborative study, examining bedside nutrition practice, illustrates some of the challenges to the provision of nutrition support and highlights opportunities for practice modification. Fasting for procedures and intolerance to EN were the commonest reasons for prolonged EN interruptions. Interventions aimed at optimizing EN delivery must be designed after examining existing barriers to EN and directed at high-risk individuals who are most likely to benefit from these interventions. In our study, patients with EN interruptions were younger, more likely to need mechanical ventilation, were more likely to be fed via the post-pyloric route and had a longer stay in the PICU. Educational intervention and practice changes targeted at these high-risk patients may decrease the incidence of avoidable interruptions to EN in critically ill children. The potential impact of such an intervention on clinical outcomes is exciting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Drover JW, Gramlich L, Dodek P. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for nutrition support in mechanically ventilated, critically ill adult patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003 Sep-Oct;27(5):355–373. doi: 10.1177/0148607103027005355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore FA, Moore EE, Haenel JB. Clinical benefits of early post-injury enteral feeding. Clin Intensive Care. 1995;6(1):21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamaoui E, Lefkowitz R, Olender L, et al. Enteral nutrition in the early postoperative period: a new semi-elemental formula versus total parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1990 Sep-Oct;14(5):501–507. doi: 10.1177/0148607190014005501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore FA, Feliciano DV, Andrassy RJ, et al. Early enteral feeding, compared with parenteral, reduces postoperative septic complications. The results of a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 1992 Aug;216(2):172–183. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199208000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chellis MJ, Sanders SV, Webster H, Dean JM, Jackson D. Early enteral feeding in the pediatric intensive care unit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1996 Jan-Feb;20(1):71–73. doi: 10.1177/014860719602000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers EJ, Gilbertson HR, Heine RG, Henning R. Barriers to adequate nutrition in critically ill children. Nutrition. 2003 Oct;19(10):865–868. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(03)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adam S, Batson S. A study of problems associated with the delivery of enteral feed in critically ill patients in five ICUs in the UK. Intensive Care Med. 1997 Mar;23(3):261–266. doi: 10.1007/s001340050326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canete A, Duggan C. Nutritional support of the pediatric intensive care unit patient. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1996 Jun;8(3):248–255. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199606000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1989. pp. 171–173. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyland D, Cook DJ, Winder B, Brylowski L, Van deMark H, Guyatt G. Enteral nutrition in the critically ill patient: a prospective survey. Crit Care Med. 1995 Jun;23(6):1055–1060. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199506000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClave SA, Sexton LK, Spain DA, et al. Enteral tube feeding in the intensive care unit: factors impeding adequate delivery. Crit Care Med. 1999 Jul;27(7):1252–1256. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor RM, Preedy VR, Baker AJ, Grimble G. Nutritional support in critically ill children. Clin Nutr. 2003 Aug;22(4):365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(03)00033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meert KL, Daphtary KM, Metheny NA. Gastric vs small-bowel feeding in critically ill children receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2004 Sep;126(3):872–878. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Groof F, Joosten KF, Janssen JA, et al. Acute stress response in children with meningococcal sepsis: important differences in the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor I axis between nonsurvivors and survivors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002 Jul;87(7):3118–3124. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Leavitt K, Duggan C. Severe weight loss and hypermetabolic paroxysmal dysautonomia following hypoxic ischemic brain injury: the role of indirect calorimetry in the intensive care unit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008 May-Jun;32(3):281–284. doi: 10.1177/0148607108316196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raff T, Hartmann B, Germann G. Early intragastric feeding of seriously burned and long-term ventilated patients: a review of 55 patients. Burns. 1997 Feb;23(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(96)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson F, Doig GS. Parenteral vs. enteral nutrition in the critically ill patient: a meta-analysis of trials using the intention to treat principle. Intensive Care Med. 2005 Jan;31(1):12–23. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2511-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClave SA, Dryden GW. Critical care nutrition: reducing the risk of aspiration. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2003 Jan;14(1):2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClave SA, Snider HL. Clinical use of gastric residual volumes as a monitor for patients on enteral tube feeding. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002 Nov-Dec;26(6 Suppl):S43–48. doi: 10.1177/014860710202600607. discussion S49-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin HC, Van Citters GW. Stopping enteral feeding for arbitrary gastric residual volume may not be physiologically sound: results of a computer simulation model. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1997 Sep-Oct;21(5):286–289. doi: 10.1177/0148607197021005286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamion F, Hamelin K, Duflo A, Girault C, Richard JC, Bonmarchand G. Gastric emptying in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: effect of neuromuscular blocking agent. Intensive Care Med. 2003 Oct;29(10):1717–1722. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1898-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClave SA, Lukan JK, Stefater JA, et al. Poor validity of residual volumes as a marker for risk of aspiration in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2005 Feb;33(2):324–330. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000153413.46627.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrillo-Albarano T, Pettignano R, Asfaw M, Easley K. Use of a feeding protocol to improve nutritional support through early, aggressive, enteral nutrition in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006 Jul;7(4):340–344. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000225371.10446.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyons KA, Brilli RJ, Wieman RA, Jacobs BR. Continuation of transpyloric feeding during weaning of mechanical ventilation and tracheal extubation in children: a randomized controlled trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002 May-Jun;26(3):209–213. doi: 10.1177/0148607102026003209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez C, Lopez-Herce J, Carrillo A, Mencia S, Vigil D. Early transpyloric enteral nutrition in critically ill children. Nutrition. 2007 Jan;23(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Briassoulis G, Zavras N, Hatzis T. Malnutrition, nutritional indices, and early enteral feeding in critically ill children. Nutrition. 2001 Jul-Aug;17(7-8):548–557. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briassoulis GC, Zavras NJ, Hatzis MT. Effectiveness and safety of a protocol for promotion of early intragastric feeding in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2001 Apr;2(2):113–121. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Lucas C, Moreno M, Lopez-Herce J, Ruiz F, Perez-Palencia M, Carrillo A. Transpyloric enteral nutrition reduces the complication rate and cost in the critically ill child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000 Feb;30(2):175–180. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200002000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creel AM, Winkler MK. Oral and nasal enteral tube placement errors and complications in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007 Mar;8(2):161–164. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000257035.54831.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]