Abstract

Background

Self-report questions in substance use research and clinical screening often ask individuals to reflect on behaviors, symptoms, or events over a specified time period. However, there are different ways of phrasing conceptually similar time frames (e.g., past year vs. past 12 months).

Methods

We conducted focused, abbreviated cognitive interviews with a sample of community health center patients (N=50) to learn how they perceived and interpreted questions with alternative phrasing of similar time frames (past year vs. past 12 months; past month vs. past 30 days; past week vs. past 7 days).

Results

Most participants perceived the alternative time frames as identical. However, 28% suggested that the “past year” and “past 12 months” phrasings would elicit different responses by evoking distinct time periods and/or calling for different levels of recall precision. Different start and end dates for “past year” and “past 12 months” were reported by 20% of the sample. There were fewer discrepancies for shorter time frames.

Conclusions

Use of “past 12 months” rather than “past year” as a time frame in self-report questions could yield more precise responses for a substantial minority of adult respondents.

Scientific Significance

Subtle differences in wording of conceptually similar time frames can affect the interpretation of self-report questions and the precision of responses.

Introduction

Time-bound retrospective self-report is a mainstay of behavioral health research and clinical care. Questions about whether or how often an individual engages in a behavior or experiences an event within a defined reference period, such as the number of cigarettes smoked in the past 30 days or number of hospitalizations in the past year, are widely used in epidemiology, clinical research, and patient care.

Self-report questions depend on the respondent's ability to 1) correctly comprehend the question, and 2) retrieve and report an accurate response.1,2 It is well-established in survey research that responses can be influenced by subtle changes in question wording or format.1,3,4 One way the context of a question can be altered is through the reference period (i.e., time frame) in which participants are asked to recall activities or experiences. Prior research has examined the effects of reference period length on memory and recall.5,6 While shorter reference periods may improve recall,6,7 they may not capture infrequent behaviors or events (e.g., hospitalizations). Although research has examined how participants respond to different reference periods (e.g., past week vs. past year), there has been less attention to comprehension and interpretation of questions phrased using conceptually similar reference periods (e.g., past 12 months vs. past year).

There is a lack of consensus on this point in commonly used self-report measures in the substance use field. For example, the CRAFFT tool's8,9 prescreening section asks “During the Past 12 months, did you...”, while the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)10 asks about alcohol use in the “Past Year.” The impact of reference period phrasing on individual responses to time-bound retrospective self-report of substance use has not been studied.

In the current preliminary qualitative study, we used an abbreviated cognitive interviewing approach to examine interpretive differences for conceptually similar reference periods in a sample of medical patients. Cognitive interviewing was developed in the 1980s by survey methodologists and psychologists to evaluate sources of response error in questionnaires. Supported by a large body of research, cognitive interviewing is one of the primary methods used by survey researchers to test the accuracy with which items are understood and answered by respondents.11-14

Methods

This study conducted abbreviated cognitive interviews focused on reference periods in time-bound retrospective self-report. Participants (N=50) were primary care patients recruited from a waiting area at a community health clinic. A trained research assistant approached adult patients in the waiting area and invited them to participate in a short anonymous interview about survey questions while they waited. Interviews were conducted using a probing script. The study was approved by the Friends Research Institute Institutional Review Board with a waiver of written informed consent. No compensation was provided. Data about refusal rates and participants’ background characteristics were not collected as part of this focused data collection effort.

Abbreviated Cognitive Interview

The abbreviated cognitive interviews examined participants’ perspectives on commonly-used alternative wording for three time frames:

past year vs. past 12 months;

past month vs. past 30 days; and

past week vs. past 7 days.

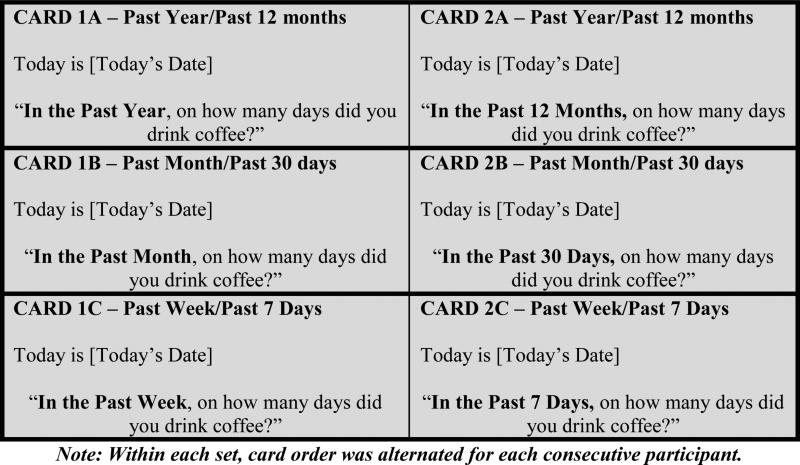

The interviewer began with the script: “We are studying how people think about time frames when asked survey questions. I'm going to show you two different ways of asking a question about drinking coffee.” (Coffee consumption was selected to provide a uniform, non-sensitive behavioral target). The interviewer then presented participants with two flash cards (alternating the top card for every other participant; Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Reference period prompts presented to participants.

After showing the first card, the interviewer asked

“What is the time frame that you think of when answering this question?”, and wrote down participants’ response verbatim. Follow-up probes asked participants to identify the date range encompassed by the question (start and end date). The process was repeated for the second card. After participants identified the date range for both cards, the interviewer queried participants about their thought processes using the following questions:

Do you think these two questions are asking about the same time period or a different time period? [Follow-up: How are they different?]

If you were just answering this question on a survey, would you actually think back to a specific date, or estimate somehow? [If time frame was interpreted differently: How about for this one?]

Could you describe your thought process when thinking about how to answer this question? [If different: How about for this one?]

Participants’ responses were logged verbatim using a structured data collection form. This process was repeated for question sets comparing past month vs. past 30 days, and past week vs. past 7 days.

Data from the structured form were entered into an Excel spreadsheet. Perceptive differences within each question set were identified on the basis of participants’ verbatim responses and assignment of distinct start/end dates. Discrepancies between start and end dates were calculated, and cross-checked against the participants’ verbatim responses to the probes. The focused nature of the data collection allowed all verbatim statements to be examined and tabulated in Excel without the use of specialized software. The first and second author examined the start/end dates and quotes independently, then met to establish consensus.

Results

Although most participants reported that the alternative phrasings were functionally identical, we identified two patterns of discrepancy: 1) differences in the perceived amount of time encompassed in the reference period, and 2) differences in the precision of self-report associated with different phrasings. Below we report the findings from the study, including calculations of the prevalence of different interpretations, supported by illustrative verbatim quotes from participants.

Past year vs. Past 12 months

Overall, most participants (72%) judged the ‘past year’ and ‘past 12 months’ to be the same (e.g., “Is this a trick? No? Ok! They are the same thing.”). Nevertheless, 28% (n=14) indicated that the two phrasings would elicit different responses or ways of thinking through the question. This included 20% (n=10) who provided different date ranges for the two questions. Seven of these 10 interpreted ‘past year’ to indicate January through December of the previous year, rather than a year from the interview date. Moreover, some participants perceived the ‘past year’ question as requiring a less precise answer than the ‘past 12 months’ version, as exemplified by the quotes below which are illustrative of the perceptive discrepancies experienced by participants for these different phrasing options:

“One year feels like a less definite amount of time, like there's wiggle room. Twelve months is more exact.”

“A year feels...nebulous in a way. It's the same amount of time, but asking in terms of 12 months feels like you want a more precise answer.”

“12 months is a hard amount of time. A year feels looser.”

Past month vs. Past 30 days

Only 3 participants (6%) perceived differences between ‘past month’ vs. ‘past 30 days’. Two of these participants interpreted ‘past month’ to mean the previous calendar month (e.g., August 1st – August 31st for participants interviewed in mid-September). However, 14% (n=7) reported that they would be more exact in reporting behavior when asked about the ‘past 30 days’ compared to the ‘past month’. One participant explained, “In this case, I would say they cover the same amount of time, but I would tend to be more exact if the question were phrased using the precise amount of time in question.”

Past week vs. Past 7 days

One participant reported a difference between ‘past week’ and ‘past 7 days’, stating that the ‘past week’ implied the previous week starting on Sunday through Saturday. Two participants reported that they would formulate more precise responses to ‘past 7 days’ vs. ‘past week’.

Discussion

This study used focused, abbreviated cognitive interviewing strategies to examine perceived differences between conceptually similar time frames in retrospective behavioral self-report. Our findings suggest that while most participants perceived alternative phrasings to cover the same time period, a substantial minority reported that questions using the ‘past year’ vs. ‘past 12 months’ reflected distinct time windows or evoked responses of differing precision.

Different applications of behavioral self-report have different requirements with respect to accurate time frame alignment and response precision. If accuracy of the time frame and precision of responses are paramount, phrasing questions with more specific time frames (e.g., ‘past 12 months’ rather than ‘past year’) could convey more clearly the time span of interest. Moreover, some individuals presented with what is perceived as a more specific time frame might be more likely to respond in kind, reflecting more carefully on the question and in turn enhancing the precision of responses. An alternative and more robust approach used in some face-to-face and computer-based surveys is to provide the participant with the target date range directly for each question (although the inclusion of more specific information can have the potential drawback of increasing cognitive load).1 Nevertheless, not all applications of self-report will require deep reflection or high-precision responses, and most individuals will perceive no differences between reference period phrasings.

This preliminary qualitative study has several limitations. Participants were recruited from a single health center in the southwestern USA. The sample size is relatively small, and it is possible that complete saturation of interpretations was not achieved. While the approach may lack the rigor of traditional extended cognitive interviewing methods,15 our abbreviated cognitive interviews were designed to be rapidly deployed during a healthcare visit and to offer insights about how alternative time frames are interpreted and perceived. We were limited to asking one type of question about frequency of coffee consumption, and did not have the opportunity to probe more deeply into participants’ perceptions. Finally, the study was anonymous and no participant information was collected. Thus, we could not analyze the impact of participant characteristics on perception. Future larger-scale research could test hypotheses related to the accuracy of self-report for different time periods by posing questions that could be verified by objective data sources.

Our findings suggest that the phrasing of time frames is worth careful attention when designing behavioral self-report questions, particularly with longer time horizons.

Acknowledgments

source of funding: The study was supported through National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grant No. U10DA013034 and R01DA026003 (PI Schwartz). Neither NIDA nor the National Institutes of Health had any role in the design and conduct of the study; data acquisition, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Schwarz N, Oyserman D. Asking questions about behavior: Cognition, communication, and questionnaire construction. American Journal of Evaluation. 2001;22(2):127–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudman S, Bradburn NM. Asking questions: A practical guide to questionnaire design. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1983. p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwarz N. Self-reports: How the questions shape the answers. American Psychologist. 1999;54(2):93–105. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler FJ., Jr. Improving survey question: Design and evaluation. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. p. 191. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winkielman P, Knäuper B, Schwarz N. Looking back at anger: Reference periods change the interpretation of emotion frequency questions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(3):719–28. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blair E, Burton S. Cognitive processes used by survey respondents to answer behavioral frequency questions. Journal of Consumer Research. 1987;14(2):280–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown NR. Encoding, representing, and estimating event frequencies: A multiple strategy perspective. In: Betsch T PS, editor. Frequency Processing & Cognition. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2002. pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, Harris SK, Chang G. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediat Adol Med. 2002;156(6):607–14. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT. Screening instruments for substance use and brief interventions targeting adolescents in primary care: a literature review. Addict Behav. 2013;38(5):2146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): An Effective Brief Screening Test for Problem Drinking. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller K, Chepp V, Willson S, Padilla JL. Cognitive Interviewing Methodology. John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins D. Cognitive Interviewing Practice. SAGE Publications; London: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willis GB, Royston P, Bercini D. The use of verbal report methods in the development and testing of survey questionnaires. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1991;5:251–67. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willis G. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boeije H, Willis G. The Cognitive Interviewing Reporting Framework (CIRF): Towards the Harmonization of Cognitive Testing Reports. Methodology. 2013;9(3):87–95. [Google Scholar]