Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the association between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and pterygium.

Methods

Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008–2011 were used for the present epidemiologic study. A total of 19,178 participants aged ≥ 30 years were evaluated for blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and performed ophthalmic slit lamp examinations. Pterygium was considered as a growth of fibrovascular tissue over the cornea.

Results

The average blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were 18.6 ng/mL, and prevalence of pterygium was 6.5%. The odds of pterygium significantly increased across blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D quintiles after controlling sun exposure time as well as other confounders such as sex, age, smoking, diabetes, hypertension (P < 0.001). The odds ratios (OR) for pterygium was 1.51 (95% Confidence Interval[95%CI]; 1.19–1.92) in the highest blood vitamin D quintile. Stratified analysis by sex showed a positive association between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and pterygium in both men (quintile 5 versus 1, OR; 1.68, 95%CI; 1.19–2.37) and women (quintile 5 versus 1, OR; 1.37, 95% CI; 1.00–1.88).

Conclusions

Even after controlling sun light exposure time, we found a positive association between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and pterygium in a representative Korean population. The mechanism underlying this association is unknown.

Introduction

Pterygium is a benign uncontrolled growth of conjunctiva. It can significantly disturb the visual function in advanced cases through irregular astigmatism, impaired tear film regularity, or visual occlusion by a large pterygium over the visual axis. In addition, associated inflammation can lead to conjunctival injection and ocular discomfort. Although the full pathophysiology of pterygium is unclear, ultraviolet-mediated limbal damage is a risk factor for initiation of pterygium [1, 2]. In addition, the development of pterygium involves epidermal proliferation [3], inflammatory infiltration [4], angiosis and fibrosis [5], and alteration in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition [6]. Recently, it has been reported that the S100 proteins, which are calcium-activated signaling proteins, may be associated with the formation of pterygium [7]. Pterygium tissue showed higher expression of S100 proteins than normal conjunctival tissue.

Vitamin D has not only function of calcium regulation but also other biologic functions such as anti-inflammation or anti-oxidation [8–10]. Vitamin D was inversely associated with chronic inflammation in many human studies [11]. Various ocular diseases including myopia [12], age-related macular degeneration [13], and diabetic retinopathy [14, 15] was found to be related with vitamin D. Our previous work demonstrated that vitamin D was inversely related with cataract [16], diabetic retinopathy [17], and age-related macular degeneration [18] in representative Korean population. In addition we reported no association between vitamin D and dry eye syndrome, which implicated the differential effect of vitamin D on ocular diseases [19].

However, epidemiologic studies on the association between vitamin D levels and pterygium are very limited. The results from our previous studies on the inverse association between blood vitamin D and cataract and age-related macular degeneration [17, 18] are interesting considering that 90% of vitamin D is generated in the skin through sunlight, which has been implicated as a risk factor for cataract and age-related macular degeneration [20–23]. Similarly, the mechanism underlying pathogenesis of pterygium includes sunlight exposure as a risk factor for pterygium [1, 2]. Thus, blood vitamin D levels have the possibility playing a role in pathogenesis of pterygium. In this study, the possible relationship between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and pterygium was evaluated in Korean adults. In addition, our result for pterygium was compared to the results of our previous reports about association between vitamin D and age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, cataract, and dry eye syndrome.

Methods

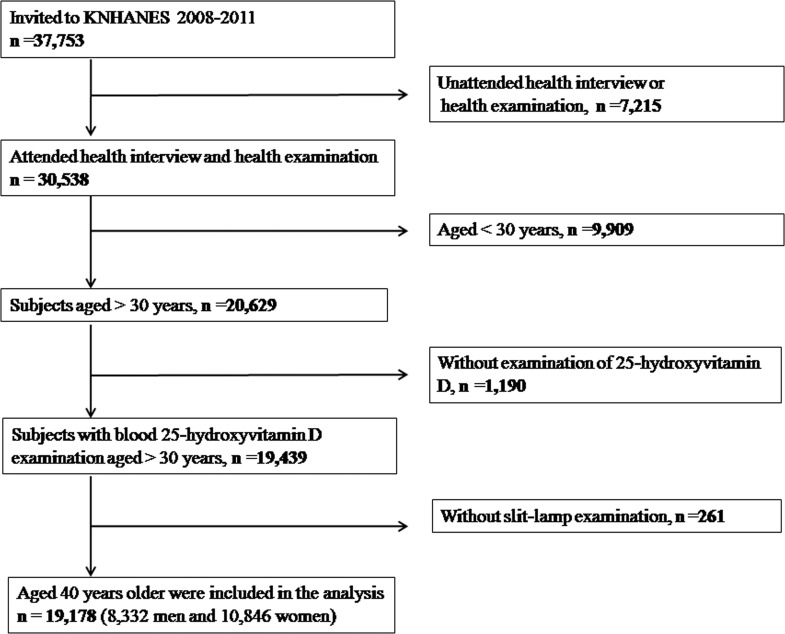

The study design followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for biomedical research. Protocols for this study were approved by the institutional review board at the Catholic University of Korea in Seoul. All participants provided written informed consent. We used data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Details about the study design and the methods used have been reported elsewhere [24, 25]. KNHANES is a nationwide and population-based cross-sectional study. For the present study, we included data obtained from KNHANES 2008–2011. For the current study, 30,538 individuals who took part in KNHANES were enrolled. Of these, 9,909 participants aged <30 years, 1,190 participants without blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, and 1,190 participants without information on the presence of pterygium were excluded from the study. Thus, 19,178 participants were used in the final analysis (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Flow diagram showing the selection of study participants.

The analysis of blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels has been described elsewhere [26, 27]. A radioimmunoassay kit (DiaSorin Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA) was used for measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels using a gamma counter (1470 Wizard, Perkin-Elmer, Finland), followed by the standardization of vitamin D procedure [28]. Blood samples were collected after an 8-h fast, and they were transported to a laboratory of the Neodin Medical Institute after appropriate process. The measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin D had the detection limit of 1.2 ng/ml. Interassay coefficients of variation were 2.8–6.2% for KNHANES 2008–2009, and 1.9–6.1% for for KNANES 2010–2011. A Hitachi 7600 clinical analyzer (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used for measurement of other clinical variables including total cholesterol, glucose, triglyceride and hemoglobin A1c levels.

The measurement of pterygium in KNHANES was documented in detail previously [29]. Briefly, slit-lamp eye examinations by a BQ 900® (Haag-Streit AG; Koeniz, Switzerland) were used for participants. Pterygium was defined as a growth of fibrovascular tissue over the cornea. Other clinical and demographic characteristics were determined as follows. We calculated body mass indices by dividing weight (kg) by height (m)2. Diabetes mellitus was considered to be present when the subjects take anti-glycemic medication or a fasting blood-glucose level was more than126 mg/dL. Hypertension was considered to be present when subjects take antihypertensive medication or a systolic and diastolic blood pressure was more than 140 mmHg and 90 mmHg, respectively. Sunlight exposure time was evaluated by questionnaire whether subjects have sunlight exposure more than 5 hours per day or not. Smoking status was examined by questionnaire classifying participants into three categories: current, past, or non smokers.

The SPSS® version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) were used for statistical analyses. Since KNHANES used stratified, multistage sampling method, we incorporated sampling weights as well as strata, sampling units in the statistical analysis. Continuous variables were presented with the mean and standard error (SE), and categorical variables were presented with the percentage and SE. To compare the patients’ demographic characteristics ANOVA or chi-square tests were used. We used logistic regression analyses after categorization of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels into quintiles. To evaluate the confounding effect by confounders, we calculated three odds ratio (OR); the crude OR (Model 1), age and sex adjusted OR (Model 2), and sex, age, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and sunlight exposure times adjusted OR (Model 3). We tested multicollinearity, and exclude variables which has a variance inflation factor more than 5 for the logistic regression analyses. P values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistical significance.

Results

The average blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were 18.6 ng/mL (SE, 0.1%). The prevalence of pterygium in both genders was 6.5% (SE, 0.3%). The prevalence of pterygium was 6.8% (SE, 0.3%) in men and 6.3% (SE, 0.3%) in women. Table 1 showed that participants with pterygium was significantly associated with old age, diabetes, hypertension, higher systolic blood pressure, higher fasting glucose levels, higher 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, and higher sun-exposure times (P for all variables above < 0.001), compared with those without pterygium.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics, according to pterygium status in the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008–2011.

| Characteristics | No pterygium (n = 17630) | Pterygium (n = 1548) | P | Included (n = 19178) | no exam (n = 261) | p | Total (n = 19439) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 49.7 (0.3) | 51.9 (1.5) | .145 | 49.8 (0.3) | 54.5 (3.4) | .170 | 49.9 (0.3) |

| Age (yrs) | 48.9 (0.1) | 61.7 (0.4) | < .001 | 49.7 (0.1) | 49.2 (0.9) | .645 | 49.5 (0.5) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.8 (0.0) | 23.9 (0.1) | .329 | 23.8 (0.0) | 24.0 (0.2) | .549 | 23.9 (0.1) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 119.3 (0.2) | 126.5 (0.6) | < .001 | 119.8 (0.2) | 121.0 (1.3) | .363 | 120.4 (0.7) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77.7 (0.1) | 78.4 (0.4) | .104 | 77.8 (0.1) | 79.2 (0.9) | .124 | 78.5 (0.4) |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 98.5 (0.2) | 102.1 (0.9) | < .001 | 98.7 (0.2) | 103.9 (2.2) | .023 | 101.3 (1.1) |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.0 (0.0) | 6.2 (0.1) | .012 | 6.1 (0.0) | 6.1 (0.1) | .542 | 6.1 (0.1) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190.9 (0.3) | 192.3 (1.2) | .254 | 191.0 (0.3) | 188.4 (2.6) | .342 | 189.7 (1.3) |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 142.3 (1.2) | 143.7 (3.1) | .684 | 142.4 (1.1) | 151.8 (8.7) | .282 | 147.1 (4.4) |

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D (ng/mL) | 18.5 (0.1) | 20.4 (0.2) | < .001 | 18.6 (0.1) | 18.0 (0.5) | .290 | 18.3 (0.3) |

| Diabetes (%) | 9.8 (0.3) | 14.6 (1.2) | < .001 | 10.1 (0.3) | 12.2 (2.5) | .390 | 10.2 (0.3) |

| Hypertension (%) | 31.0 (0.5) | 48.4 (1.7) | < .001 | 32.1 (0.5) | 33.9 (3.5) | .602 | 32.1 (0.5) |

| Sun exposure (%) | < .001 | .715 | |||||

| > 5hrs/day | 19.6 (0.6) | 35.1 (1.9) | 20.6 (0.7) | 19.3 (3.5) | 20.6 (0.7) | ||

| < 5hrs/day | 80.4 (0.6) | 64.9 (1.9) | 79.4 (0.7) | 80.7 (3.5) | 79.4 (0.7) | ||

| Smoking status | .059 | .296 | |||||

| Never (%) | 52.2 (0.4) | 52.6 (1.5) | 52.2 (0.4) | 47.3 (3.8) | 52.2 (0.4) | ||

| Former (%) | 12.0 (0.3) | 14.6 (1.1) | 12.2 (0.3) | 11.1 (2.6) | 12.2 (0.3) | ||

| Current (%) | 35.8 (0.5) | 32.8 (1.5) | 35.6 (0.4) | 41.6 (3.9) | 35.7 (0.4) |

Data are expressed as weighted means or weighted frequency (%) with standard errors.

As quintiles of blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, subjects had a tendency to be male (P < 0.001), older (P < 0.001), hypertensive (P < 0.001), diabetic (P = 0.031), smoker (P < 0.001), and have higher fasting glucose (P = 0.010), higher total cholesterol (P = 0.006), and experienced longer sun exposures (P < 0.001, Table 2).

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics by quintile blood 25-Hydroxyvitamin D categories among representative Korean adults aged 19 years or older.

| Characteristics | Quartile blood 25-Hydroxyvitamin D level (ng/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 13.0 | 13.0–16.3 | 16.3–19.6 | 19.6–24.3 | > 24.3 | P for trend | |

| Number | 3845 | 3833 | 3841 | 3841 | 3828 | |

| Male (%) | 36.7 (0.9) | 43.4 (1.0) | 51.5 (0.9) | 56.8 (1.0) | 62.3 (0.9) | < .001 |

| Age (yrs) | 48.0 (0.3) | 48.2 (0.2) | 48.8 (0.3) | 50.8 (0.3) | 53.1 (0.4) | < .001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.5 (0.1) | 24.0 (0.1) | 23.9 (0.1) | 24.1 (0.1) | 23.7 (0.1) | < .001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 118.6 (0.3) | 118.7 (0.3) | 119.3 (0.3) | 120.6 (0.3) | 121.8 (0.4) | < .001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76.8 (0.2) | 77.5 (0.2) | 77.9 (0.2) | 78.4 (0.2) | 78.3 (0.2) | < .001 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 98.1 (0.5) | 97.7 (0.4) | 99.7 (0.5) | 98.7 (0.4) | 99.5 (0.4) | .010 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.1 (0.0) | 5.9 (0.0) | 6.1 (0.0) | 6.0 (0.0) | 6.2 (0.1) | .001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 189.0 (0.7) | 190.7 (0.7) | 191.9 (0.7) | 193.2 (0.7) | 190.0 (0.6) | < .001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 143.3 (2.9) | 146.4 (2.7) | 140.5 (2.3) | 143.1 (2.3) | 138.4 (1.8) | .147 |

| Diabetes (%) | 9.8 (0.6) | 8.8 (0.6) | 10.4 (0.6) | 10.1 (0.6) | 11.1 (0.6) | .031 |

| Hypertension (%) | 29.3 (0.9) | 29.9 (0.9) | 30.4 (0.9) | 34.3 (1.0) | 37.2 (1.0) | < .001 |

| Sun exposure (>5hrs/day, %) | < .001 | |||||

| < 5hrs/day | 87.7 (0.7) | 85.9 (0.8) | 82.3 (0.9) | 74.9 (1.2) | 64.4 (1.6) | |

| > 5hrs/day | 12.3 (0.7) | 14.1 (0.8) | 17.7 (0.9) | 25.1 (1.2) | 35.6 (1.6) | |

| Smoking status | < .001 | |||||

| Never (%) | 60.3 (1.0) | 55.8 (1.0) | 52.3 (1.0) | 48.0 (1.0) | 43.7 (1.0) | |

| Former (%) | 8.8 (0.6) | 11.8 (0.7) | 13.2 (0.6) | 15.1 (0.8) | 12.1 (0.8) | |

| Current(%) | 30.9 (1.0) | 32.3 (1.0) | 34.6 (0.9) | 36.9 (1.1) | 44.1 (1.1) | |

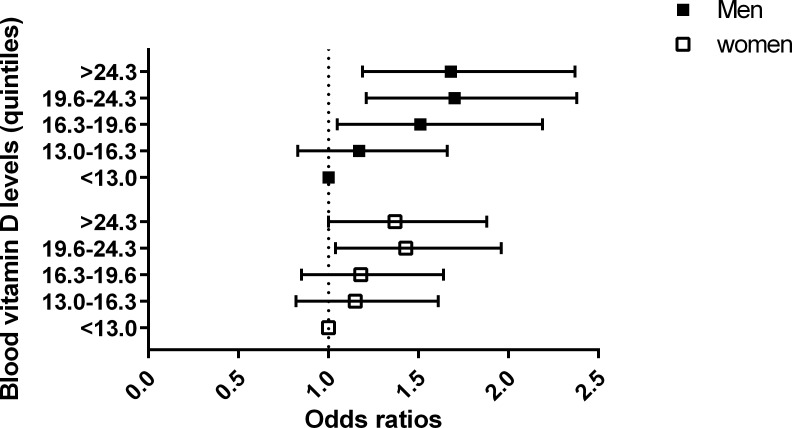

As the quintiles of the blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels increased, the odds of pterygium significantly increased (P < 0.001). Even after controlling potential confounders mentioned above, this positive association remained still strong and significant (P < 0.001, Table 3). OR for pterygium in highest quintile of blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels over lowest one is 2.20 (P < 0.001, 95%CI; 1.75–2.77). After controlling potential confounders, OR for pterygium in quintile 5 over quintile 1 is 1.51 (P < 0.001, 95%CI; 1.19–1.92, Fig 2). Stratified analysis by gender demonstrated that after adjusting for potential confounders, the association between higher blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the increasing odds of pterygium were significant both in men (quintile 5 versus 1, OR; 1.68, 95% CI; 1.19–2.37,) and women (OR; 1.37, 95% CI; 1.00–1.88,).

Table 3. Association between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D and prevalence of pterygium among representative Korean adults.

| Vitamin D quintiles (ng/mL) | Case/total number | Prevalence | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both gender | 6.5 (0.3) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (<13.0) | 205/3845 | 4.4 (0.4) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Quintile 2 (13.0–16.3) | 243/3833 | 5.1 (0.4) | 1.17 (0.94–1.47) | 1.20 (0.96–1.52) | 1.20 (0.95–1.22) |

| Quintile 3 (16.3–19.6) | 291/3841 | 6.5 (0.5) | 1.50 (1.20–1.88)* | 1.49 (1.18–1.88)* | 1.39 (1.10–1.75)* |

| Quintile 4 (19.6–24.3) | 366/3841 | 7.8 (0.6) | 1.84 (1.43–2.29)* | 1.58 (1.26–1.98)* | 1.48 (1.17–1.86)* |

| Quintile 5 (>24.3) | 443/3828 | 9.2 (0.6) | 2.20 (1.75–2.77)* | 1.63 (1.29–2.06)* | 1.51 (1.19–1.92)* |

| P for trend | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | |

| Men | 6.8 (0.3) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (<14.3) | 91/1672 | 4.4 (0.5) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Quintile 2 (14.3–17.7) | 119/1666 | 5.3 (0.6) | 1.21 (0.87–1.70) | 1.23 (0.91–1.81) | 1.17 (0.83–1.66) |

| Quintile 3 (17.7–21.1) | 138/1665 | 6.8 (0.8) | 1.61 (1.14–2.27)* | 1.50 (1.05–2.14)* | 1.51 (1.05–2.19)* |

| Quintile 4 (21.1–25.9) | 186/1667 | 8.6 (0.8) | 2.07 (1.51–2.83)* | 1.78 (1.29–2.45)* | 1.70 (1.21–2.38)* |

| Quintile 5 (>25.9) | 211/1662 | 9.7 (0.9) | 2.35 (1.70–3.25)* | 1.78 (1.28–2.49)* | 1.68 (1.19–2.37)* |

| P for trend | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | |

| Women | 6.3 (0.3) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (<12.2) | 112/2169 | 4.5 (0.5) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Quintile 2 (12.2–15.2) | 130/2170 | 5.0 (0.5) | 1.11 (0.82–1.51) | 1.17 (0.84–1.62) | 1.15 (0.82–1.61) |

| Quintile 3 (15.2–18.3) | 144/2172 | 5.7 (0.6) | 1.29 (0.94–1.75) | 1.28 (0.93–1.76) | 1.18 (0.85–1.64) |

| Quintile 4 (18.3–22.7) | 189/2170 | 7.5 (0.7) | 1.71 (1.26–2.31)* | 1.57 (1.15–2.15)* | 1.43 (1.04–1.96)* |

| Quintile 5 (>22.7) | 228/2165 | 8.9 (0.8) | 2.07 (1.54–2.79)* | 1.53 (1.13–2.08)* | 1.37 (1.00–1.88)* |

| P for trend | < .001 | < .001 | .001 | .016 |

Prevalence was expressed as weighted estimates [%] (standard errors [%], 95% confidence intervals).

Model 1: Crude odds ratios. Model 2: adjusted for sex and age. Model 3: adjusted for sex, age, diabetes, hypertension, sunlight exposure time, smoking, and body mass index.

* p < 0.05

Fig 2. The odds ratios of pterygium according to quintiles of blood vitamin D levels (reference group = lowest vitamin D quintile group).

Discussion

Our study is the first to evaluate the association between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and pterygium. We found that even after adjusting for the sun light exposure time, the adjusted odds of pterygium was associated with the increasing quintiles of the blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, and blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were positively associated with of the prevalence of pterygium. Based on this unexpected result we hypothesized that blood vitamin D levels have an inverse association with the prevalence of pterygium.

The exact mechanism underlying this relationship is unknown. One possible explanation is that high vitamin D levels may elevate blood calcium levels and activate a calcium-activated signaling protein, S100 protein, which has been implicated as a cause of pterygium development [7]. Many pathophysiology in pterygium development including angiogenesis, transdifferentiation, and cellular proliferation may be contributed to calcium signaling activities [2]. A recent in vitro study demonstrated that calcium-free bathing medium made from blood reduced the number of pterygium-derived fibroblasts, which is the main causal cell in pterygium development [30]. In addition, suppressed calcium signaling activity reduced the growth rates of pterygian-derived fibroblasts [30]. It suggests that the calcium store plays important role in pathophysiology of pterygian-derived fibroblasts. Thus, a higher level of vitamin D may elevate the cellular calcium levels, which would enhance the calcium signaling development of pterygium through S100 protein. However, we could not assess the blood calcium levels or S100 protein levels. Further studies are required to identify the relationship between blood calcium levels and pterygium.

Another possible explanation is the residual confounding factor of sun exposure on the association between vitamin D and pterygium. Because the majority of vitamin D is synthesized in the skin from sunlight, the subjects with high blood vitamin D levels could have experienced longer sun exposure times. Although we adjusted for sun exposure time in model 3, it is a dichotomous variable (≥ 5 h or < 5 h/day). There is a possibility that sun exposure is a residual confounding factor. However, the association between vitamin D and pterygium was consistently strong both before and after adjusting for sun exposure time. Thus, it is unlikely that the residual confounding factor of sun exposure time would cause the strong positive association between blood vitamin D and pterygium. The contribution of sun exposure time is further supported by a comparison of our results with the results of previous studies involving age-related macular degeneration and cataract, in which sunlight exposure was an established risk factor [16–19].

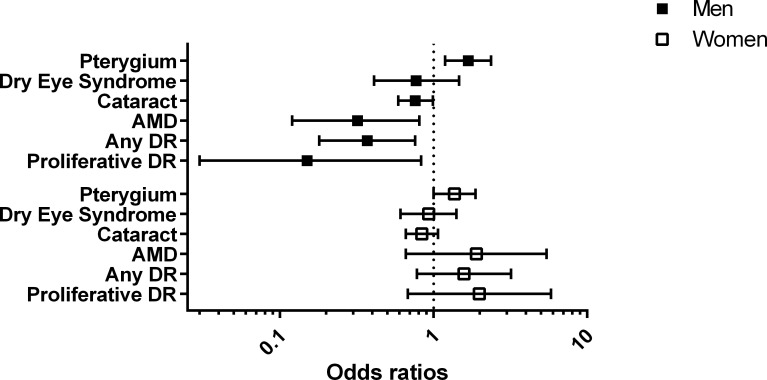

We compared the association of pterygium with those for four other ocular diseases (diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, cataract, and dry eye syndrome) from our previous reports which have used the same KNHANES population (Fig 3) [16–19]. The blood vitamin D levels were inversely associated with the ocular diseases, although the strength of association was different among the ocular diseases. In men, the ORs of late age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, cataract, and dry eye syndrome were 0.32 (95% CI, 0.12–0.81), 0.37 (95% CI, 0.18–0.76), 0.76 (95% CI, 0.59–0.99), and 0.85 (95% CI, 0.55–1.30), respectively. However, in the present study, the blood vitamin D levels were positively associated with pterygium (OR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.19–2.37). Moreover, the association between vitamin D and pterygium was stronger than those of other diseases, given that the relative odds of pterygium in those with 3rd, 4th,and 5th vitamin D quintiles versus the lowest one were significantly increased, whereas relative odds of other ocular diseases in those with only 5th vitamin D quintile versus lowest one was significantly decreased. In addition, the association between vitamin D and pterygium was shown in both men and women, whereas the association between vitamin D and other ocular diseases has been shown only in men, not women. These comparisons imply that the underlying mechanism of association between blood vitamin D and pterygium may be different from those of the association between blood vitamin D and other diseases (diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, cataract, and dry eye syndrome) in our previous reports [16–19].

Fig 3. The comparison of odds ratios of ocular diseases including dry eye syndrome (DES), cataract, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), any diabetic retinopathy (DR), and vision-threatening DR (VTDR) according to the blood vitamin D levels (reference group = lowest vitamin D quintile group).

The average vitamin D concentration (18.6 ng/mL) was low and in the range indicating mild to moderate vitamin D insufficiency in clinical guidelines. These findings are supported by a previous study of Korea, in which prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency was 47.5% in men, and 64.5% in women [31]. In addition, young adults aged 20–29 years showed the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency 65.0% in men and 79.9% in women. It implicates the vitamin D insufficiency could be a greater threat to younger generation in Korea.

The present study has both strength and limitations. Strength is the large number of participants in the present study. Another strength is the study’s design of nation-wide survey with stratified, multi-clustered sampling. Limitation of this study is that seasonal variations of vitamin D levels were not considered. Unfortunately, KNHANES does not have information on sampling season. A recent study showed that an Asian population did not display any significant seasonal variation in vitamin D status [32]. However, another study reported significant seasonal variation with lower vitamin D levels in winter [33]. Another limitation is that our study measured only 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, which may not sufficient to reflect the body vitamin D levels. The current dogma is that vitamin D is activated by 25-hydroxylation and then 1,25-hydroxylation. Recently, novel pathways of vitamin D3 were found [34]. Slominski et al discovered the novel sequential hydroxylation that starts at carbon-20, which is initiated by CYP11A1.[35–38] Predominant pathway is from vitamin D3 through 20-hydroxyvitamin D to 20,23-hydroxyvitamin D.[37] Finally, our study design is a cross-sectional study, which introduced difficulties in reasoning causality.

In conclusion, our study is the first analysis of population-based epidemiologic data on the association between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and pterygium. We found a positive association between blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and pterygium even after adjusting for the confounder of sun light exposure time, which is contrary to the results of our previous studies. The mechanism underlying this association is unknown and warrants further study.

Data Availability

Third-party data are owned by the Korea Center for Chronic Disease and Control. Interested researchers may submit requests for data to Tel:82-43-719-7466 or Email: choym527@korea.kr (Division of Health and Nutrition Survey, KCDC) or Osong Health Technology Administration Complex, 187 Osongsaengmyeong2 (i)-ro, Osong-eup, Heungduk-gu, Cheongju-si, Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea 363-700 (Tel: +82-43-719-7464,63 E-mail: KNHANES@korea.kr).

Funding Statement

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2015R1A1A1A05028023).

References

- 1.Coroneo MT. Pterygium as an early indicator of ultraviolet insolation: a hypothesis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77(11):734–9. Epub 1993/11/01. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc504636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coroneo MT, Di Girolamo N, Wakefield D. The pathogenesis of pterygia. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1999;10(4):282–8. Epub 2000/01/06. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan DT, Liu YP, Sun L. Flow cytometry measurements of DNA content in primary and recurrent pterygia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(7):1684–6. Epub 2000/06/14. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Girolamo N, Wakefield D, Coroneo MT. UVB-mediated induction of cytokines and growth factors in pterygium epithelial cells involves cell surface receptors and intracellular signaling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(6):2430–7. Epub 2006/05/26. 10.1167/iovs.05-1130 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu T, Liu Y, Xie L, He X, Bai J. Progress in the pathogenesis of pterygium. Curr Eye Res. 2013;38(12):1191–7. Epub 2013/09/21. 10.3109/02713683.2013.823212 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chui J, Di Girolamo N, Wakefield D, Coroneo MT. The pathogenesis of pterygium: current concepts and their therapeutic implications. The ocular surface. 2008;6(1):24–43. Epub 2008/02/12. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riau AK, Wong TT, Beuerman RW, Tong L. Calcium-binding S100 protein expression in pterygium. Molecular Vision. 2009;15:335–42. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez JA, Chowdhury R, Jones DP, Martin GS, Brigham KL, Binongo JN, et al. Vitamin D status is independently associated with plasma glutathione and cysteine thiol/disulfide redox status in adults. Clinical endocrinology. 2014. Epub 2014/03/19. 10.1111/cen.12449 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uberti F, Lattuada D, Morsanuto V, Nava U, Bolis G, Vacca G, et al. Vitamin D protects Human Endothelial Cells from oxidative stress through the autophagic and survival pathways. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013:jc20132103. Epub 2013/11/29. 10.1210/jc.2013-2103 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangge H, Weghuber D, Prassl R, Haara A, Schnedl W, Postolache TT, et al. The Role of Vitamin D in Atherosclerosis Inflammation Revisited: More a Bystander than a Player? Current vascular pharmacology. 2013. Epub 2013/12/18. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant W, Strange R, Garland C. Sunshine is good medicine. The health benefits of ultraviolet‐B induced vitamin D production. Journal of cosmetic dermatology. 2003;2(2):86–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi JA, Han K, Park YM, La TY. Low Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Is Associated with Myopia in Korean Adolescents. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014. Epub 2014/02/01. 10.1167/iovs.13-12853 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parekh N, Chappell RJ, Millen AE, Albert DM, Mares JA. Association between vitamin D and age-related macular degeneration in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 through 1994. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(5):661–9. Epub 2007/05/16. 10.1001/archopht.125.5.661 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payne JF, Ray R, Watson DG, Delille C, Rimler E, Cleveland J, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency in diabetic retinopathy. Endocrine Practice. 2012;18(2):185–93. 10.4158/EP11147.OR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patrick PA, Visintainer PF, Shi Q, Weiss IA, Brand DA. Vitamin D and retinopathy in adults with diabetes mellitus. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(6):756–60. Epub 2012/07/18. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.2749 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jee D, Kim EC. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and age-related cataracts. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2015;41(8):1705–15. Epub 2015/10/04. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.12.052 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jee D, Han K, Kim EC. Inverse association between high blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and diabetic retinopathy in a representative Korean population. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115199 Epub 2014/12/09. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115199 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4259490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim EC, Han K, Jee D. Inverse Relationship between High Blood 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Late Stage of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in a Representative Korean Population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014. Epub 2014/07/13. 10.1167/iovs.14-14763 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jee D, Kang S, Yuan C, Cho E, Arroyo JG. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels and Dry Eye Syndrome: Differential Effects of Vitamin D on Ocular Diseases. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149294 Epub 2016/02/20. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149294 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sui GY, Liu GC, Liu GY, Gao YY, Deng Y, Wang WY, et al. Is sunlight exposure a risk factor for age-related macular degeneration? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(4):389–94. Epub 2012/11/13. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302281 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts JE. Ultraviolet radiation as a risk factor for cataract and macular degeneration. Eye & contact lens. 2011;37(4):246–9. Epub 2011/05/28. 10.1097/ICL.0b013e31821cbcc9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucas RM. An epidemiological perspective of ultraviolet exposure—public health concerns. Eye & contact lens. 2011;37(4):168–75. Epub 2011/06/15. 10.1097/ICL.0b013e31821cb0cf . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalam KV, Khetpal V, Rusovici R, Balaiya S. A review: role of ultraviolet radiation in age-related macular degeneration. Eye & contact lens. 2011;37(4):225–32. Epub 2011/06/08. 10.1097/ICL.0b013e31821fbd3e . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Y, Park S, Kim NS, Lee BK. Inappropriate survey design analysis of the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey may produce biased results. Journal of preventive medicine and public health = Yebang Uihakhoe chi. 2013;46(2):96–104. Epub 2013/04/11. 10.3961/jpmph.2013.46.2.96 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3615385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park HA. The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey as a primary data source. Korean journal of family medicine. 2013;34(2):79 Epub 2013/04/06. 10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.2.79 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3611106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eum K-D, Lee M-S, Paek D. Cadmium in blood and hypertension. Science of the Total Environment. 2008;407(1):147–53. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee M-S, Park SK, Hu H, Lee S. Cadmium exposure and cardiovascular disease in the 2005 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environmental research. 2011;111(1):171–6. 10.1016/j.envres.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sempos CT, Vesper HW, Phinney KW, Thienpont LM, Coates PM. Vitamin D status as an international issue: national surveys and the problem of standardization. Scandinavian journal of clinical and laboratory investigation Supplementum. 2012;243:32–40. Epub 2012/06/08. 10.3109/00365513.2012.681935 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rim TH, Nam J, Kim EK, Kim TI. Risk factors associated with pterygium and its subtypes in Korea: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008–2010. Cornea. 2013;32(7):962–70. Epub 2013/02/28. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182801668 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang C, Illingworth CD, Qian L, Wormstone IM. Serum deprivation can suppress receptor-mediated calcium signaling in pterygial-derived fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(7):4563–70. Epub 2013/06/14. 10.1167/iovs.13-11604 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi HS, Oh HJ, Choi H, Choi WH, Kim JG, Kim KM, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency in Korea—a greater threat to younger generation: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2008. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96(3):643–51. Epub 2010/12/31. 10.1210/jc.2010-2133 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith M. Seasonal, ethnic and gender variations in serum vitamin D3 levels in the local population of Peterborough. Bioscience Horizons. 2010;3(2):124–31. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee YA, Kim HY, Hong H, Kim JY, Kwon HJ, Shin CH, et al. Risk factors for low vitamin D status in Korean adolescents: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2008–2009. Public health nutrition. 2014;17(4):764–71. Epub 2013/03/07. 10.1017/s1368980013000438 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slominski A, Semak I, Zjawiony J, Wortsman J, Li W, Szczesniewski A, et al. The cytochrome P450scc system opens an alternate pathway of vitamin D3 metabolism. The FEBS journal. 2005;272(16):4080–90. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04819.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slominski AT, Li W, Kim TK, Semak I, Wang J, Zjawiony JK, et al. Novel activities of CYP11A1 and their potential physiological significance. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;151:25–37. Epub 2014/12/03. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slominski AT, Kim T-K, Li W, Postlethwaite A, Tieu EW, Tang EKY, et al. Detection of novel CYP11A1-derived secosteroids in the human epidermis and serum and pig adrenal gland. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:14875 10.1038/srep14875 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slominski AT, Kim TK, Shehabi HZ, Semak I, Tang EK, Nguyen MN, et al. In vivo evidence for a novel pathway of vitamin D(3) metabolism initiated by P450scc and modified by CYP27B1. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2012;26(9):3901–15. Epub 2012/06/12. 10.1096/fj.12-208975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slominski AT, Kim TK, Chen J, Nguyen MN, Li W, Yates CR, et al. Cytochrome P450scc-dependent metabolism of 7-dehydrocholesterol in placenta and epidermal keratinocytes. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2012;44(11):2003–18. Epub 2012/08/11. 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Third-party data are owned by the Korea Center for Chronic Disease and Control. Interested researchers may submit requests for data to Tel:82-43-719-7466 or Email: choym527@korea.kr (Division of Health and Nutrition Survey, KCDC) or Osong Health Technology Administration Complex, 187 Osongsaengmyeong2 (i)-ro, Osong-eup, Heungduk-gu, Cheongju-si, Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea 363-700 (Tel: +82-43-719-7464,63 E-mail: KNHANES@korea.kr).