Abstract

Black spot disease, caused by Alternaria alternata Japanese pear pathotype, is one of the most harmful diseases in Japanese pear cultivation. In the present study, the locations of black spot disease resistance/susceptibility-related genome regions were studied by fluorescence in situ hybridization using BAC clone (BAC-FISH) on Japanese pear (Pyrus pyrifolia (Burm. f.) Nakai) chromosomes. Root tips of self-pollinated seedlings of ‘Osa Gold’ were used as materials. Chromosome samples were prepared by the enzymatic maceration and air-drying method. The BAC clone adjacent to the black spot disease-related gene was labeled as a probe for FISH analysis. Black spot disease-related genome regions were detected in telomeric positions of two medium size chromosomes. These two sites and six telomeric 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA sites were located on different chromosomes as determined from the results of multi-color FISH. The effectiveness of the physical mapping of useful genes on pear chromosomes achieved by the BAC-FISH method was unequivocally demonstrated.

Keywords: Alternaria, bacterial artificial chromosome, chromosome, disease resistance, fluorescence in situ hybridization

Introduction

Pears (Pyrus spp.) are among the most important fruit tree species cultivated in temperate regions. Among the species, Japanese pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) is common in Japan. In Japanese pear cultivation, black spot disease, caused by the Japanese pear pathotype of Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissler, is one of the most harmful diseases. Bagging of fruit and frequent spraying of fungicide to prevent infection are necessary for the cultivation of disease-sensitive cultivars. A host-specific toxin called AK-toxin causes necrosis and early leaf fall in disease sensitive cultivars (Otani et al. 1985) such as ‘Nijjiseiki’, one of the most common pear cultivars in Japan. This disease resistance/susceptibility is controlled by a single gene and susceptibility and resistance are dominant and recessive, respectively (Kozaki 1973).

Since resistance to black spot disease is one of the most important breeding objectives in Japanese pear breeding programs, this trait is the principal research subject in pear genome studies. Seventeen linkage groups corresponding to the basic chromosome number (n = 17) have been constructed (Yamamoto et al. 2007) and a black spot disease-related gene was located at the top region of linkage group (LG) 11 (Terakami et al. 2007). Moreover, Terakami et al. (2012) produced a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone adjacent to the black spot disease-related gene.

Chromosome information is also important for genetic and biotechnological studies. Therefore, we have continued to study the chromosomes of pears. As a consequence, an enzymatic maceration method, preparing good chromosome samples from pear with small chromosomes, was developed (Yamamoto et al. 2010) and the number and location of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sites were detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) (Yamamoto et al. 2010, 2012). However, the locations of important genes of pears such as disease resistance have not been elucidated. Visualization of the location of agronomic important genes on chromosomes by FISH was reported in some plants (Fukui and Ohmido 2000, Iwano et al. 1998, Ohmido et al. 1998). In fruit trees, agronomic important genes were also detected on chromosomes by FISH using BAC clones (BAC-FISH) including those gene regions as probes (Mendes et al. 2011, Minamikawa et al. 2010). Thus, BAC-FISH seems to show promise for the detection of agronomic important genes on chromosomes in pear and the result will be an important information for progress in pear genetics, breeding, and genome studies. In the present study, we performed FISH using a BAC clone adjacent to the black spot disease-related gene in Japanese pear.

Materials and Methods

Plant material, enzyme maceration/air-drying (EMA), Giemsa staining and BAC clone

Japanese pear ‘Osa Gold’ (accession number: JP110825 of NIAS Genebank, Japan, http://www.gene.affrc.go.jp/index_en.php) was used. The materials used in this study were obtained from the NARO Institute of Fruit Tree Science, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan. ‘Osa Gold’ is a resistant mutant to the black spot disease derived from ‘Osanijisseiki’, a self-compatible bud sport of ‘Nijisseiki’, by chronic irradiation of gamma-rays (Table 1) (Masuda et al. 1998, Sato 1993). Although mechanism of mutation of ‘Osa Gold’ has not been elucidated, it seems that resistance of this cultivar is imperfect and possesses disease susceptible gene; some disease susceptible progenies were appeared from cross combinations between ‘Osa Gold’ crossed with disease resistant cultivars (Terakami et al. unpublished data).

Table 1.

Origin of Japanese pear (P. pyrifolia) cultivars used in the present study

| Cultivar | Origin |

|---|---|

| Osa Gold | An artificial mutant of Osanijisseiki (A spontaneous mutant of Nijisseiki) |

| Kinchaku | A local cultiver unknown origin |

| Hosui | Kosui (Kikusui (Taihaku × Nijisseiki) × Wasekozo) × Hiratsuka No. 1 (Ishiiwase × Nijisseiki) |

Roots of young seedlings from self-pollination were the source of the material used in this study. Seeds were germinated in Petri dishes at 12°C in the dark. Root tips of approximately 1 cm in length were excised, immersed in 2 mM 8-hydroxyquinoline at 10°C for 4 h in the dark, fixed in methanol-acetic acid (3:1) and stored at −20°C.

Enzymatic maceration and air-drying were performed as described by Fukui (1996) with minor modifications (Yamamoto et al. 2010). The root tips were washed in distilled water to remove the fixative and macerated in an enzyme mixture containing 4% Cellulase Onozuka RS (Yakult, Japan), 1% Pectolyase Y-23 (Seishin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Japan) and 1 mM EDTA, pH 4.2, at 37°C for 3 h.

Chromosomes were stained with 2% Giemsa solution (Merck Co., Germany) in 1/30 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) for 15 min, rinsed with distilled water, air-dried and then mounted with xylene. After confirmation of each chromosome’s position on the slide under a microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i, Japan), the chromosomes were destained with 70% methanol.

A BAC library was constructed from Japanese pear cultivar ‘Kinchaku’ (Table 1) showing black spot disease susceptibility with 16 times coverage of its genome (Kim et al. 2011). The BAC clone “307_G15” (approximately 150 kb) was isolated very close position to the Aki (susceptibility gene of ‘Kinchaku’) region, and BAC DNAs were prepared as described by Ashikawa et al. (2008).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and Multicolor FISH (McFISH)

The BAC clone “307_G15” adjacent to the black spot disease-related gene was labeled with biotin following the standard nick translation protocol (BioNick Labeling System, Invitrogen, Japan). FISH was performed according to the method of Ohmido and Fukui (1996) with minor modifications (Yamamoto et al. 2010). The hybridization mixture contained 125 ng labelled probe/slide, 50% formamide, 2 × SSC, and 3750 ng salmon sperm DNA/slide. Since heavy non-specific reaction was observed without blocking DNA, unlabeled whole DNA of ‘Hosui’ (P. pyrifolia) was used as blocking DNA and mixed with a labeled probe in the hybridization mixture. The concentration of the tested blocking DNA was ten to fifty times greater than that of labeled probe. The DNA was sheared to an average size of ca. 400 bp by autoclaving at 105°C for 5 min. Since more than 1/3 of genome of ‘Hosui’ was derived from ‘Nijisseiki’, the original cultivar of ‘Osa Gold’ (Sawamura et al. 2004), ‘Osa Gold’ and ‘Hosui’ is closely related (Table 1). Moreover, diversity among cultivated Japanese pear (P. pyrifolia) was very small (Iketani et al. 2012). Thus, genomic DNA of ‘Hosui’ using in the present study is considered to block DNA of ‘Osa Gold’. After hybridization overnight, the biotinylated probe was detected with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-avidin conjugate (Fluorescein Avidin DN, Vector, USA) by fluorescence microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE 80i, Japan). FITC signals were visualized using a FITC filter. Chromosomes were counterstained with 2.0 mg·L−1 DAPI in an antifadant solution (Vector Shield; Vector Laboratories, USA) and visualized using a UV filter. Signal images were captured using a microscopy digital camera (DP71, Olympus, Japan) and analyzed using imaging software (DP-BSW Ver. 03.01, Olympus, Japan).

Multicolor FISH (McFISH) of the BAC clone “307_G15” and 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA was performed according to the method of Shishido et al. (2001) with minor modifications (Yamamoto et al. 2012). The latter is a 9.0 kb fragment including a full-length 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA repeat unit of wheat (Barker et al. 1988, Gerlach and Bedbrook 1979). The BAC clone was labeled with biotin. The 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA probes were labeled with digoxigenin by nick translation (DIG-Nick translation kit, Roche, Germany). The concentrations of hybridization mixture and the blocking DNA were the same as in the FISH described above. After hybridization overnight, the biotinylated and digoxigenin labelled probes were detected with a FITC-avidin conjugate and anti-digoxigenin rhodamine Fab fragments (Roche, Germany)/Texas Red anti-sheep IgG (Vector Laboratories, USA), respectively. The chromosome samples were observed with a fluorescence microscope. FITC signals (BAC clone) were visualized using an FITC filter. Rhodamine/Texas Red signals (18S-5.8S-25S rDNA) were visualized using a G-2A filter. Chromosomes counterstained with DAPI were visualized using a UV filter. Signal images were captured using a microscopy digital camera and analyzed using imaging software. From the preparation stained with DAPI, five cells were selected for use in determining chromosome length.

Results

A number of signals were detected when BAC-FISH was performed without blocking DNA. Then, we conducted BAC-FISH with whole-genome DNA of pear as blocking DNA. In general, the number of detected signals is fewer at forty to fifty times at the concentration of blocking DNA than ten to twenty times at the concentration of it. However, sometimes a few signals were detected at ten times at the concentration of blocking DNA and several signals were detected at fifty times the concentration of it.

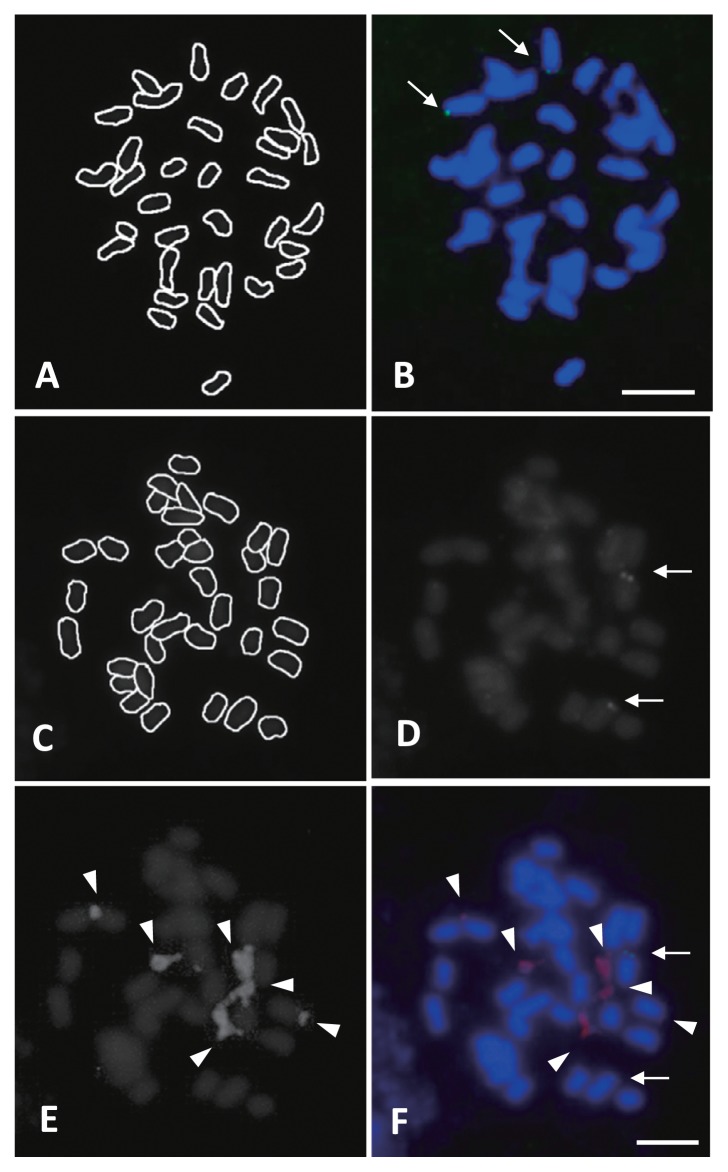

Schematic representation of somatic chromosomes of self-pollinated seedlings of ‘Osa Gold’ (2n = 34) was shown in Fig. 1A and 1C. Fig. 1B and 1D show metaphase chromosomes counterstained with DAPI. The black spot disease-related genome regions were detected as green fluorescent signals. These genome regions were located in telomeric positions of two chromosomes. In at least one spread of each ten slides with forty- to fifty-fold excess of total genomic DNA compared with the probe DNA, the detection of repetitive sequences could be suppressed efficiently by blocking DNA, the number and position of the disease-related genome regions were stable, and there was no difference among the seedlings from self-pollination.

Fig. 1.

A and C: Schematic representation of somatic chromosomes of self-pollinated seedlings of ‘Osa Gold’ (2n = 34). B and D: FISH of BAC clone including black spot disease-related region. E: FISH of 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA. F: McFISH of BAC clone including black spot disease-related region and 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA. Arrows and arrow heads indicate the black spot disease-related region and 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA, respectively. Bar = 5 μm.

Next, we performed McFISH of the BAC clone adjacent to the black spot disease-related gene and 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA. In situ hybridization with the 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA probe revealed signals on six chromosomes. The six signal sites were located in telomeric regions of the six chromosomes (Fig. 1E). The 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA sites were stable, and there was no difference among the seedlings from self-pollination. The two telomeric black spot disease-related genome regions and six telomeric 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA sites were located on different chromosomes, as determined from the results of McFISH (Fig. 1F).

Table 2 shows the relative length of chromosomes derived from self-pollinated seedlings of ‘Osa Gold’. The length of chromosomes ranged from 4.1% to 2.1%. The two black spot disease-related genome regions were located on medium (3.1%) chromosomes.

Table 2.

The relative length (% of the total length) of each 34 chromosome derived from self-pollinated seedlings of ‘Osa Gold’

| Chromosome | Relative length (%) |

|---|---|

| Chromosomes with the black spot disease-related region | |

| 1 and 2 | 3.1 ± 0.1a |

| Chromosomes without the black spot disease-related region | |

| 3 | 4.1 ± 0.2 |

| 4 | 3.8 ± 0.2 |

| 5 | 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| 6 | 3.6 ± 0.1 |

| 7 | 3.5 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | 3.4 ± 0.1 |

| 9 | 3.4 ± 0.1 |

| 10 | 3.2 ± 0.1 |

| 11 | 3.2 ± 0.1 |

| 12 | 3.1 ± 0.1 |

| 13 | 3.1 ± 0.1 |

| 14 | 3.1 ± 0.1 |

| 15 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| 16 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| 17 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| 18 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| 19 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| 20 | 2.8 ± 0.1 |

| 21 | 2.8 ± 0.1 |

| 22 | 2.8 ± 0.1 |

| 23 | 2.7 ± 0.1 |

| 24 | 2.7 ± 0.1 |

| 25 | 2.7 ± 0.1 |

| 26 | 2.6 ± 0.1 |

| 27 | 2.6 ± 0.1 |

| 28 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| 29 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| 30 | 2.0 ± 0.1 |

| 31 | 2.4 ± 0.1 |

| 32 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| 33 | 2.2 ± 0.1 |

| 34 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

Standard error.

Discussion

Many signals were detected when BAC-FISH was performed without blocking DNA. This result probably indicated that a repeated sequence including the BAC clone hybridized with various chromosome regions possessing on identical or very similar sequence. This phenomenon is commonly observed in BAC-FISH in higher plants (Suzuki et al. 2001, Zwick et al. 1997). Hybridization with genomic DNA or highly repetitive DNA such as Cot-1 as a competitor is suppressed to detect the repetitive sequence (Jiang et al. 1995, Ohmido et al. 1998, Zwick et al. 1997). Ohmido et al. (1998) reported that the effectiveness of genomic DNA and Cot-1 was basically the same. Since isolation of Cot-1 is a time-consuming and laborious process compared with extraction of genomic DNA (Yamamoto personal communication), genomic DNA was used for blocking. In the present study also, the use of whole-genome DNA of pear as blocking DNA is essential for the detection of the black spot disease-related genome regions on pear chromosomes.

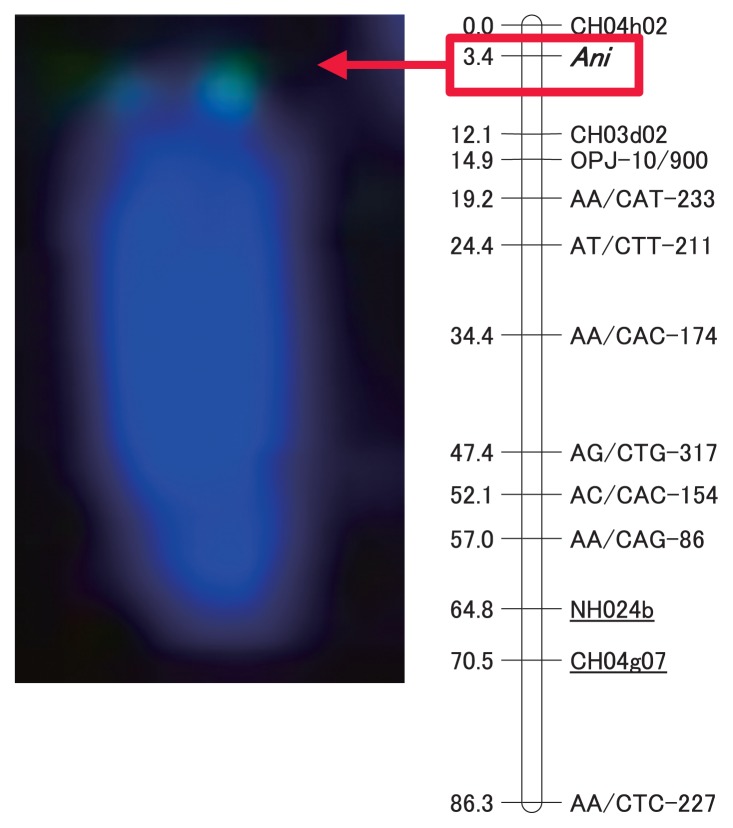

Although resistance to black spot disease is one of the most important research subject in pear genome studies, a candidate gene of black spot disease resistance/susceptibility has not been identified up to the present. Whole genome sequences were recently reported for Chinese pear ‘Dangshansuli’ (Wu et al. 2013) and European pear (Chagné et al. 2014). However, since these pear genome sequences were not anchored to 17 chromosomes, physical position of black spot disease susceptibility gene was not identified. Very recently, Terakami et al. (2016) finely mapped the Aki gene for susceptibility to black spot disease in the Japanese pear ‘Kinchaku’, similar to the positions of the Ani gene in ‘Osa Nijisseiki’ and the Ana gene in ‘Nansui’, at the top of linkage group 11, suggesting that their responsible genes from different genetic resources exist in close genome positions, and have the similar gene functions for black spot susceptibilities. Since the Aki region in ‘Kinchaku’ showed co-linearity to the chromosome 11 of apple genome of ‘Golden Delicious’ (Velasco et al. 2010), the Aki locus was identified within a 1.5-cM genome region, whose size was estimated to be 250 Kb (position of 2,915–3,165 Kb) in the apple genome of ‘Golden Delicious’, using a synteny-based approach (Terakami et al. 2016). In the present study, a BAC clone “307_G15” was used for FISH screened by the apple SSR marker CH04h02, which showed high sequence similarity to the apple genome contig MDC010914.246 (e-value: 1e-116), corresponding to the positions of 231,017–250,688 bp of apple chromosome 11. Therefore, the BAC “307_G15” would be 2.5-Mb apart from the Aki gene based on the apple genome sequences.

As seen in Fig. 1, the BAC “307_G15” clearly identified telomeric position of two chromosome 11, which was very close to the Aki region, even if the BAC does not contain the Aki gene. Seventeen linkage groups, corresponding to the basic chromosome number (n = 17) were already constructed in pear (Yamamoto et al. 2007). In addition, Terakami et al. (2007) revealed that a black spot disease-related gene was located at the top (3.4 cM from the end) of linkage group (LG) 11. In our BAC-FISH experiment, the BAC clone adjacent to this gene was used as a probe. The positions of the signals correspond to the position of the black spot disease-related gene revealed by linkage analysis (Fig. 2). Therefore, the signals detected at a telomeric position by BAC-FISH were considered to be the black spot disease-related genome regions on pear chromosomes. Based on the results of McFISH, it was revealed that two black spot disease-related genome regions and six 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA sites were located on different chromosomes. From the combinations of existence of 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA sites and length of chromosomes, discrimination of chromosomes with these rDNA sites was possible (Yamamoto et al. 2012). Detection of a chromosome pair with black spot disease-related genome regions was possible in the present study. These results provide useful information for discrimination of pear chromosomes.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between chromosome possessing black spot disease-related genome region and linkage group (LG) 11 in Japanese pear. Ani: A gene for susceptibility to black spot in Japanese pear (Terakami et al. 2007).

The distribution of relative length of chromosomes in the present study (4.1–2.1%) (Table 2) and those in the previous study (4.0–2.0%) (Yamamoto et al. 2012) were almost the same. In the latter study, the two 5S rDNA sites were located on relatively short (2.6 and 2.5%) chromosomes that do not possess 18S-5.8S-25S rDNA sites, whereas the two black spot disease-related genome regions were located on medium (3.1%) chromosomes in the present study. Thus, black spot disease-related genome regions and two 5S rDNA sites were probably located at different chromosomes based on the results of both studies. In addition, relative length of approximately half the number of chromosomes is of medium size. The chromosomes with black spot disease-related genome regions could be easily distinguished in these medium size chromosomes. These results also provide useful information for discrimination of pear chromosomes.

This is the first report to show the location of an agronomic important gene on pear chromosomes, although FISH of rDNA genes has already been conducted (Yamamoto et al. 2010, 2012). In apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) and citrus (Citrus spp.), both major temperate and sub-tropical fruit trees, the chromosomal locations of agronomic important genes were elucidated (Mendes et al. 2011, Minamikawa et al. 2010). Both a self-incompatibility gene of apple and a citrus tristeza virus (CTV) resistance region of citrus were detected by FISH using BAC clones as probes. The present study also visualized black spot disease-related genome regions by BAC-FISH. These results indicate the effectiveness of BAC-FISH for the detection of agronomic important genes on fruit tree chromosomes.

As mentioned above, the black spot disease-related genome regions found to be located at LG11. Thus, the chromosomes possessing BAC-FISH signals correspond to LG11. This is also the first report to identify relationships between chromosome and linkage group in pear. Since, in the present study, only one BAC clone was used as a probe, we revealed that one chromosome corresponded to one linkage group. Elucidation of the relationships between each chromosome and linkage group is considered to be essential for the progress of breeding, genetics, and genome studies in pear. Thus, further FISH studies using BAC clones that correspond to all 17 linkage groups are necessary as in citrus, in which all nine (n = 9) chromosomes were identified based on the results of BAC-FISH (Mendes et al. 2011). In this kind of study, genome study of apple as well as that of pear seems to be very important. Apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) and pears (Pyrus spp.) belong to the subfamily Spiraeoideae, tribe Pyreae and share a basic chromosome number of x = 17. All chromosomes of pear and apple show co-linearity based on anchored SSR markers (Yamamoto et al. 2007). In addition, chromosome configuration of both genera was quite similar (Schuster et al. 1997, Yamamoto et al. 2012). Thus, information of BAC-FISH of a given genus is considered to be informative in the other genus. However, considerable differences in the genome sizes were found in the tribe Pyreae, which range from 1.11 pg/2C to 1.57 pg/2C (Dickson et al. 1992, Dirlewanger et al. 2009). The difference in size between the apple and pear genomes is mainly due to the presence of repetitive sequences (predominantly transposable elements), whereas genic regions and protein-coding genes are similar in both species. In general, same repeated sequences seem to be present in the same taxonomic group, but it can also be species specific (Mendes et al. 2011). In species belonged to Pyrae also, presence and distribution of repetitive sequences are considered to be species specific. Thus adequate experimental condition of BAC-FISH in pear can be revealed by an experiment of pear itself. In addition, since repetitive sequences present in BAC clones differ depending on the BAC clone, adequate experimental conditions of BAC-FISH should be investigated. Thus, an examination is necessary in each individual case; a combination of species and BAC clone.

Since visualization of useful genes is important in genetic and genome studies, several useful genes have been visualized on somatic chromosome of some plants (Fukui and Ohmido 2000, Iwano et al. 1998, Mendes et al. 2011, Minamikawa et al. 2010, Ohmido et al. 1998, 2005, Suzuki et al. 2001). In the present study, thus we conducted physical mapping with BAC-FISH on pear somatic chromosomes. This is considered to be the first step in chromosome and FISH studies in pear. Pachytene chromosomes at the meiotic stage are 25 times longer than those at the mitosis stage, and more accurate gene positioning by FISH is possible because of its high resolution (Ross et al. 1996). FISH to extended DNA fibers is also promising to detect accurate gene location on chromosomes (Fransz et al. 1996). However, there has been no report about FISH to meiotic chromosomes and extended DNA fiber in pear. These kinds of FISH studies are essential for genetic and genome studies.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the location of black spot disease-related genome regions on chromosomes by BAC-FISH in pear. This result could provide useful information on pear chromosomes, and is considered to contribute to the progress of breeding and genome studies in pear. In particular, the results in the present study are essential for chromosome engineering as in the study of transferring of Fusarium head blight resistance gene in wheat (Cainong et al. 2015). This result also indicates the effectiveness of the physical mapping of agronomic important genes on pear chromosomes achieved by the BAC-FISH method. However, in the present study we used the BAC clone adjacent to black spot disease-related gene. Hence, in the future, it is necessary to repeat BAC-FISH using responsible gene(s) of black spot disease resistance/susceptibility. In addition, physical mapping of several other useful genes, such as for scab resistance and self-incompatibility, should be conducted in pear.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C), Grant Number 24580046.

Literature Cited

- Ashikawa, I., Hayashi, N., Yamane, H., Kanamori, H., Wu, J., Matsumoto, T., Ono, K. and Yano, M. (2008) Two adjacent nucleotide-binding site–leucine-rich repeat class genes are required to confer Pikm-specific rice blast resistance. Genetics 180: 2267–2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker, R.F., Harberd, N.P., Jarvis, M.G. and Flavell, R.B. (1988) Structure and evolution of the intergenic region in a ribosomal DNA repeat unit of wheat. J. Mol. Biol. 201: 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cainong, J.C., Bockus, W.W., Feng, Y., Chen, P., Qi, L., Sehgal, S.K., Danilova, T.V., Koo, D.-H., Friebe, B. and Gill, B.S. (2015) Chromosome engineering, mapping, and transferring of resistance to Fusarium head blight disease from Elymus tsukushiensis into wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 128: 1019–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagné, D., Crowhurst, R.N., Pindo, M., Thrimawithana, A., Deng, C., Ireland, H., Fiers, M., Dzierzon, H., Cestaro, A., Fontana, P.et al. (2014) The draft genome sequence of European pear (Pyrus communis L. ‘Bartlett’). PLoS ONE 9: e92644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, E.E., Arumuganathan, K., Kresovich, S. and Doyle, J.J. (1992) Nuclear DNA content variation within the Rosaceae. Am. J. Bot. 79: 1081–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Dirlewanger, E., Denoyes-Rothan, B., Yamamoto, T. and Chagné, D. (2009) Genomics Tools across Rosaceae Species. In: Gardiner, S.E. and Folta K.M. (eds.) Plant Genetics/ Genomics vol 6: Genetics and Genomics of Rosaceae. Springer, New York, pp. 539–561. [Google Scholar]

- Fransz, P.F., Alonso-Blanco, C., Liharska, T.B., Peeters, A.J.M., Zabal, P. and de Jong, J.H. (1996) High-resolution physical mapping in Arabidopsis thaliana and tomato by fluorescence in situ hybridization to extended DNA fibres. Plant J. 9: 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, K. (1996) Plant chromosome at mitosis. In: Fukui, K. and Nakayama S. (eds.) Plant chromosome. Laboratory methods. CRC press, Boca Raton, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, K. and Ohmido, N. (2000) Visual detection of useful genes on plant chromosomes. JARQ 34: 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, W.L. and Bedbrook, J.R. (1979) Cloning and characterization of ribosomal RNA genes from wheat and barley. Nucleic Acids Res. 7: 1869–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iketani, H., Katayama, H., Uematsu, C., Mase, N., Sato, Y. and Yamamoto, T. (2012) Genetic structure of East Asian cultivated pears (Pyrus spp.) and their reclassification in accordance with the nomenclature of cultivated plants. Plant Syst. Evol. 298: 1689–1700. [Google Scholar]

- Iwano, M., Sakamoto, K., Suzuki, G., Watanabe, M., Takayama, S., Fukui, K., Hinata, K. and Isogai, A. (1998) Visualization of a self-incompatibility gene in Brassica campestris L. by multicolor FISH. Theor. Appl. Genet. 96: 751–757. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J., Gill, B.S., Wang, G.-L., Ronald, P.C. and Ward, D.C. (1995) Metaphase and interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization mapping of the genome with bacterial artificial chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 4487–4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H., Yamamoto, M., Hosaka, F., Terakami, S., Nishitani, C., Sawamura, Y., Yamane, H., Wu, J.Z., Matsumoto, T., Matsuyama, T.et al. (2011) Molecular characterization of novel Ty1-copia-like retrotransposons in pear (Pyrus pyrifolia). Tree Genet. Genomes 7: 845–856. [Google Scholar]

- Kozaki, I. (1973) Black spot disease resistance in Japanese pear. I. Heredity of the disease resistance. Bull. Hort. Res. Stn. A12: 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, T., Yoshioka, T., Sanada, T., Kotobuki, K., Nagara, M., Uchida, M., Inoue, K., Murata, K., Kitagawa, K. and Yoshida, A. (1998) A new Japanese pear cultivar ‘Osa Gold’, resistant mutant to the black spot disease of Japanese pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) induced by chronic irradiation of gamma-rays. Bull. Natl. Inst. Agrobiol. Resour. 12: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, S., Moraes, A.P., Mirkov, T.E. and Pedrosa-Harand, A. (2011) Chromosome homeologies and high variation in heterochromatin distribution between Citrus L. and Poncirus Raf. as evidenced by comparative cytogenetic mapping. Chromosome Res. 19: 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamikawa, M., Kakui, H., Wang, S., Kotoda, N., Kikuchi, S., Koba, T. and Sassa, H. (2010) Apple S locus region represents a large cluster of related, polymorphic and pollen-specific F-box genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 74: 143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmido, N. and Fukui, K. (1996) A new manual for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in plant chromosomes. Rice Genet. Newsl. 13: 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmido, N., Akiyama, Y. and Fukui, K. (1998) Physical mapping of unique nucleotide sequences on identified rice chromosomes. Plant Mol. Biol. 38: 1043–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmido, N., Fukui, K. and Kinoshita, T. (2005) Advances in rice chromosomes research. Proc. Japan. Acad. Ser. B 81: 382–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani, H., Kohmoto, K., Nishimura, S., Nakashima, T., Ueno, T. and Fukami, H. (1985) Biological activities of AK-toxins I and II, host-specific toxins from Alternaria alternata Japanese pear pathotype. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 51: 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, K.J., Fransz, P.F. and Jones, G.H. (1996) A light microscopic atlas of meiosis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Chromosome Res. 4: 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Y. (1993) Breeding of self-compatible Japanese pear. Tech. Gene Diag. Breed. 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, Y., Saito, T., Takada, N., Yamamoto, T., Kimura, T., Hayashi, T. and Kotobuki, K. (2004) Identification pf parentage of Japanese pear ‘Hosui’. J. Japan. Soc. Hort. Sci. 73: 511–518. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, M., Fuchs, J. and Schubert, I. (1997) Cytogenetics in fruit breeding—localization of ribosomal RNA genes on chromosomes of apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 94: 322–324. [Google Scholar]

- Shishido, R., Ohmido, N. and Fukui, K. (2001) Chromosome painting as a tool for rice genetics and breeding. Methods Cell Sci. 23: 125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, G., Ura, A., Saito, N., Do, G.S., Seo, B.B., Yamamoto, M. and Mukai, Y. (2001) BAC FISH analysis in Allium cepa. Genes Genet. Syst. 76: 251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terakami, S., Adachi, Y., Iketani, H., Sato, Y., Sawamura, Y., Takada, N., Nishitani, C. and Yamamoto, T. (2007) Genetic mapping of genes for susceptibility to black spot disease in Japanese pears. Genome 50: 735–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terakami, S., Adachi, Y., Yamane, H., Wu, J., Matsumoto, T., Kunihisa, M., Nishitani, C., Saito, T. and Yamamoto, T. (2012) Fine mapping and BAC contigs construction of the susceptible gene to black spot disease in Japanese pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai). Breed. Res. 14 (Suppl. 1): 272. [Google Scholar]

- Terakami, S., Moriya, S., Adachi, Y., Kunihisa, M., Nishitani, C., Saito, T., Abe, K. and Yamamoto, T. (2016) Fine mapping of the gene for susceptibility to black spot disease in Japanese pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai). Breed. Sci. 66: 271–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, R., Zharkikh, A., Affourtit, J., Dhingra, A., Cestaro, A., Kalyanaraman, A., Fontana, P., Bhatnagar, S.K., Troggio, M., Pruss, D.et al. (2010) The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Nat. Genet. 42: 833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., Wang, Z.W., Shi, Z.B., Zhang, S., Ming, R., Zhu, S.L., Khan, M.A., Tao, S.T., Korban, S.S., Wang, H.et al. (2013) The genome of the pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.). Genome Res. 23: 396–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, M., Terakami, S., Yamamoto, T., Takada, N., Kubo, T. and Tominaga, S. (2010) Detection of the ribosomal RNA gene in pear (Pyrus spp.) using fluorescence in situ hybridization. J. Japan. Soc. Hort. Sci. 79: 335–339. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, M., Takada, N., Yamamoto, T., Terakami, S., Shigeta, N., Kubo, T. and Tominaga, S. (2012) Fluorescent staining and fluorescence in situ hybridization of rDNA of chromosomes in pear (Pyrus spp.). J. Japan. Soc. Hort. Sci. 81: 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T., Kimura, T., Terakami, S., Nishitani, C., Sawamura, Y., Saito, T., Kotobuki, K. and Hayashi, T. (2007) Integrated reference genetic linkage maps of pear based on SSR and AFLP markers. Breed. Sci. 57: 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Zwick, M.S., Hanson, R.E., Isram-Faridi, M.N., Stelly, D.M., Wing, R.A., Price, H.J. and McKnight, T.D. (1997) A rapid procedure for the isolation of Cot-1 DNA from plants. Genome 40: 138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]