Abstract

Molecular markers associated with known quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for type 2 resistance to Fusarium head blight (FHB) in bi-parental mapping population usually have more than two alleles in breeding populations. Therefore, understanding the association of each allele with FHB response is particularly important to marker-assisted enhancement of FHB resistance. In this paper, we evaluated FHB severities of 192 wheat accessions including landraces and commercial varieties in three field growing seasons, and genotyped this panel with 364 genome-wide informative molecular markers. Among them, 11 markers showed reproducible marker-trait association (p < 0.05) in at least two experiments using a mixed model. More than two alleles were identified per significant marker locus. These alleles were classified into favorable, unfavorable and neutral alleles according to the normalized genotypic values. The distributions of effective alleles at these loci in each wheat accession were characterized. Mean FHB severities increased with decreased number of favorable alleles at the reproducible loci. Chinese wheat landraces and Japanese accessions have more favorable alleles at the majority of the reproducible marker loci. FHB resistance levels of varieties can be greatly improved by introduction of these favorable alleles and removal of unfavorable alleles simultaneously at these QTL-linked marker loci.

Keywords: wheat, Fusarium head blight, breeding population, association analysis, molecular markers, allelic effects

Introduction

Fusarium head blight (FHB) caused by Fusarium graminearum is a destructive disease in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) worldwide (Bai and Shaner 2004). Frequent FHB epidemics endanger both food security and food safety due to huge yield losses and accumulated toxins that render infected grain unsuitable for human or animal consumption (Trail 2009). In China, FHB has been reported in more than 3.3 million ha of wheat in 9 of 11 years since 2000. Severe FHB epidemics occurred in more than 10 million ha and caused yield losses of up to 100% in some locations in 2012 (Zeng and Jiang 2013).

FHB resistance is quantitatively inherited and controlled by a few major QTLs (or genes) and several modifying QTLs (or genes) (Buerstmayr et al. 2009). Mapping studies using bi-parental populations have identified more than 200 quantitative trait loci (QTL) for FHB resistance on all 21 chromosomes, and most of them were associated with type 2 resistance (Buerstmayr et al. 2009, Liu et al. 2009). Consistent and reliable QTL for FHB resistance were identified on chromosomes 2D, 3B, 3A, 5A, 6B and 7A across multiple mapping populations (Häberle et al. 2009, Liu et al. 2009, Löffler et al. 2009). Fhb1 on 3BS in ‘Sumai 3’ and its derivatives has been extensively utilized in breeding programs worldwide due to its relatively stable effects on FHB resistance when introduced into different genetic backgrounds. Breeders have strong interests in knowing the marker diagnosability and allelic variations when they are used in breeding. Despite impressive progresses in discovery of QTLs for FHB resistance, utilization of this information to develop FHB resistant varieties via marker-assisted selection (MAS) is still a challenge because most published QTLs have minor effects, or inconsistent chromosomal localization of markers and corresponding QTL among studies. Also the QTL-linked markers in one genotype may not work in a breeding panel either due to weak linkage between markers and QTLs, or due to false positives in the panel.

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) is an alternative method that compensates deficiencies of bi-parental linkage mapping and allows for examination of whether the markers that were declared to be associated with a certain QTL in bi-parental mapping population have diagnostic power in breeding panels of diverse sources, and also for characterization of allelic associations with FHB resistance in such panels (Hall et al. 2010). GWAS has recently been used in genome-wide mapping of QTL associated with FHB resistance in breeding populations of both barley (Massman et al. 2011, Navara and Smith 2014) and European wheat (Ghavami et al. 2011, Kollers et al. 2013, Miedaner et al. 2011).

Some Chinese and Japanese wheat accessions, particularly landraces, show high levels of FHB resistance (Li et al. 2011, Yu et al. 2006, Zhang et al. 2012) and therefore might harbor unique QTL or novel alleles for FHB resistance. A panel of wheat accessions consisting of both landraces and commercial varieties are ideal materials for verification of previously published QTLs/markers in bi-parental mapping populations and for identification of potentially novel QTLs or alleles associated with FHB responses. The objectives of this study were to assess FHB responses of 192 wheat accessions that were collected from diverse geographic regions to FHB infection under field conditions to identify QTLs associated with FHB resistance, and to identify effective marker alleles for use in MAS.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

A panel of 192 accessions consisting of 48 Chinese landraces, 71 Chinese commercial varieties, 27 Japanese accessions, 26 American accessions, and 19 accessions from other countries or organizations.

Evaluation of FHB responses

FHB were evaluated in the KSU FHB field nursery in three years (2011, 2012, and 2013). The nursery was arranged in a randomized complete block design. About 50 seeds per entry were planted in a 3-foot-row plot, with two replications (blocks) in each experiment. At anthesis, about 10 spikes per row were inoculated by injecting 10 μl of a conidial spore suspension (100 conidia/μl) into a central spikelet of a spike. Plants in the FHB nursery were misted for 10 min every hour using sprinklers between heading and late dough stage (Li et al. 2011). Symptomatic and total spikelets in an inoculated spike were counted at 21 d post inoculation. The percentage of symptomatic spikelets (PSS) was calculated as FHB severity. All tested accessions were classified into four classes based on FHB severity, highly resistant (0 < PSS ≤ 0.25), moderately resistant (0.25 < PSS ≤ 0.50), moderately susceptible (0.50 < PSS ≤ 0.75) and highly susceptible (0.75 < PSS ≤ 1.00).

Marker analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from two-week-old wheat leaves of each genotype using a modified CTAB method (Maguire et al. 1994). Harvested leaf tissue was dried in a freeze-dryer (ThermoSavant, Holbrook, NY, USA) for 48 h and ground using a Mixer Mill (MM 300, Retsch, Germany) for DNA isolation. A total of 364 selected informative SSR and STS primer pairs were used to genotype the population. PCR amplification followed Li et al. (2012) and amplified PCR fragments were separated in an ABI3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Marker data were scored using GeneMarker 1.6 (Softgenetics Inc. LLC, State College, PA).

Data analysis

Broad sense heritability (H2) was calculated for PSS based on analysis of variance (ANOVA) results using the formula H2 = σ2G/(σ2G + (σ2GE/e) + (σ2ɛ/re)), where σG2 = genotypic variance, σ2ɛ = residual error variance, σ2GE = genotype × environment variance, r = number of replicates (pots) and e = number of experiments following Jayatilake et al. (2011).

PSS among groups of accessions harboring different numbers of favorable alleles were compared using Turkey method at α = 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Matlab software (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

Number and frequency of alleles per locus, genetic diversity and polymorphism information content (PIC) were evaluated by PowerMarker v3.25 (Liu and Muse 2005). Population structure was determined using STRUCTURE 2.3.4 (http://pritchardlab.stanford.edu/structure.html).

TASSEL V4.3.1 (http://www.maizegenetics.net/#!tassel/c17q9) was used to identify marker-PSS associations using mixed linear model (MLM) of y = Xβ + Sα+Qv + Zu + e to minimize spurious correlations (Yu et al. 2006), where Xβ represents fixed effects other than molecular markers under test and population structure; y is a vector of phenotypic observations; β is a vector of fixed effects other than molecular marker or population group effects; α is a vector of marker effects; v is a vector of population effects; u is a vector of polygenic background effects; e is a vector of residual effects; Q is a matrix from STRUCTURE relating y to v; and X, S and Z are incidence matrices of 1s and 0s relating y to β, α and u, respectively. The variances of the random effects are assumed to be Var(u) = 2KVg, and Var(e) = RVR, where K is an n × n matrix of relative kinship coefficients defining the degree of genetic covariance between a pair of individuals; R is an n × n matrix in which the off-diagonal elements are 0 and the diagonal elements are the reciprocal of the number of observations for which each phenotypic datapoint was obtained; Vg is the genetic variance; and VR is the residual variance. Only markers that showed associations at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 were declared to be significant.

The normalized allelic values (NAV) were estimated as pi = ∑xij/ni – χ̄, where pi represents the phenotypic effect of the ith allele, xij indicates PSS of the jth variety carrying the ith allele, ni is the number of varieties carrying the ith allele, and χ̄ is the overall mean of PSS of all the varieties carrying different alleles at the marker locus of interest. The allele without significant effect on PSS across experiments was classified into a neutral or ineffective allele. If pi was significantly lower than 0, the ith allele was defined as favorable (resistant) or otherwise defined as unfavorable (susceptible). Only those accessions carrying effective alleles were regarded as a carrier of that allele.

Results and Discussion

Phenotypic variation in FHB severities

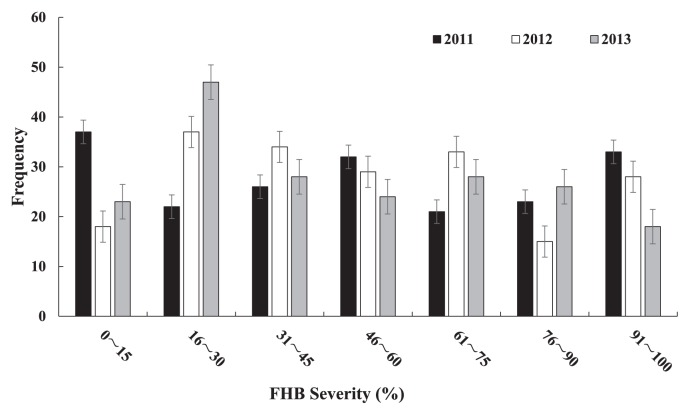

This panel of 192 wheat accessions including wheat landraces, commercial varieties and elite breeding lines were collected from 12 countries. The mean PSS of 192 accessions ranged from 5 to 100% over the three experiments (Fig. 1) with a mean of 48%. Phenotypic variation was significant among genotypes (p = 2.70e−127) and genotype-by-environment interactions (p = 3.32e−16), but not between environments (p = 7.75e−02). The PSSs were significantly correlated among the three experiments (r1–2 = 0.514, r1–3 = 0.698 and r2–3 = 0.580 at p < 0.001), and the mean heritability (H2) of PSS was 0.87 over the three experiments, suggesting the high repeatability of FHB data. Based on the mean PSSs, 43 accessions were classified highly resistant (PSS = 16.3%), 55 accessions moderately resistant (PSS = 35.5%), 60 moderately susceptible (PSS = 61.9%), and 34 highly susceptible (PSS = 83.2%). The frequencies for the accessions with high resistance, moderate resistance, moderate susceptibility, and high susceptibility were 0.23, 0.28, 0.31 and 0.18, respectively. The PSS variation of this population is of great importance for evaluation of marker diagnosability for known QTLs and for understanding allelic variation in breeding populations.

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution of the 192 wheat accessions in FHB severity (PSS) in the three experiments.

Population structure

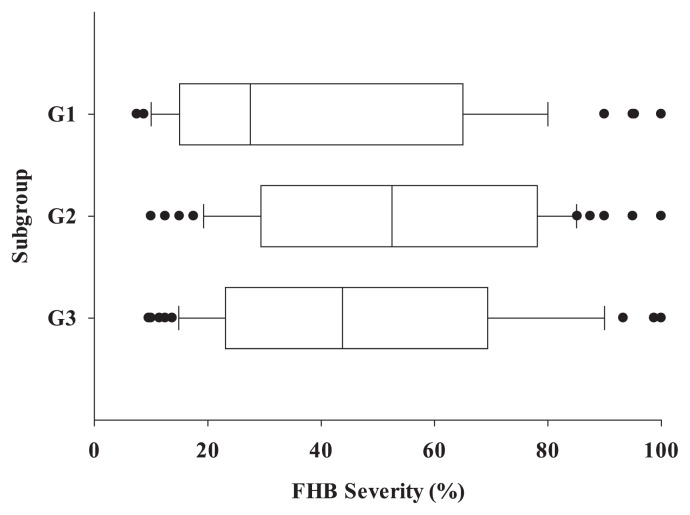

The population was divided into three groups (G1, G2 and G3) (k = 3) using the mixed model (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Fig. 1). G1 includes 60 Chinese accessions and three accessions with one each from Italy, Brazil and Japan (Supplemental Table 2). Only one Chinese landrace “Qiaomaixiaomai” fell into this group. Two well-known resistant varieties with Fhb1, ‘Sumai3’ and ‘Ning7840’, are in this group. Up to 28 of 57 commercial varieties in G1 have ‘Funo’ in their pedigrees, suggesting close relationships among these varieties. “Funo” from Italy is susceptible to FHB with a mean PSS of 70%, however, it is one of the most important backbone parents in Chinese wheat breeding programs, and more than 300 commercial varieties in China have “Funo” in their pedigrees (Si et al. 2009). The number of accessions showing high resistance, moderate resistance, moderate susceptibility and high susceptibility was 9, 21, 20 and 10, respectively. The mean PSS of G1 was 48%, ranging from 9 to 93%.

G2 includes 66 accessions with 22 from China, nine of which are Chinese landraces, 26 from the USA, and 18 from Brazil, Japan, Austria, France, Russia, Ukraine, South Korea and CIMMYT (Supplemental Table 3). As expected, G2 has the highest within-group polymorphism information content (PIC) and genetic diversity (Supplemental Table 1) due to the multiple origins of the accessions in this group. The PSS of accessions ranged from 14% to 95% with an average PSS of 52%.

G3 consists of 40 Chinese landraces, 24 Japanese accessions, one Korean accession and one Chinese commercial variety (Supplemental Table 4), therefore they are accessions from Asian countries. “Wangshuibai” (Lin et al. 2006, Yu et al. 2008), “Huangfangzhu” (Li et al. 2012), “Nyubai” (Ban et al. 2008, Cuthbert et al. 2006) carrying Fhb1 were assigned to this group. The PSS of the accessions in this group ranged from 7 to 95% with an average PSS of 38%.

The mean PSSs in order from the lowest to the highest is G3, G1 and G2, and they are significantly different among groups (p = 2.7e−03) (Fig. 2). Nei’s genetic distances of G1–G2, G1–G3 and G2–G3 were 0.090, 0.161 and 0.115, respectively. Chinese landraces and Japanese accessions were distributed in all the three groups, but predominantly in G3, suggesting a close genetic relationship among them.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the three groups in FHB severities (PSS) in the three experiments (×represents the outliers in the group).

Markers associated with PSS

In the current study, QTL repeatability over experiments was determined based on the markers that were significantly associated with FHB resistance in at least two experiments. In single experiments, 30, 32 and 13 markers were significantly associated with PSS and explained 4.1–17%, 2.5–19% and 8–16% of phenotypic variations, respectively (Supplemental Table 5). Among them, 11 markers were significant in two to three experiments (Table 1). QTLs linked to Xbarc133 and Xgwm533 on 3BS, Xgwm160 on 4AL, Xgwm261 on 2DS, Xwmc273 and Xwmc47 with undetermined chromosomal locations were reproducible across the three experiments, and each QTL explained an average 11.3% of the phenotypic variation, suggesting these QTLs are stable and these markers tightly linked to the QTLs are useful in marker-assisted breeding.

Table 1.

The phenotypic variances explained by the 11 reproducible markers in the three experiments

| Marker | Chromosome | Phenotypic variance (R2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | Mean | ||

| Xcfa2263 | 2A | 0.122 | ns | 0.158 | 0.140 |

| Xgwm249 | 2A | 0.068 | 0.069 | ns | 0.069 |

| Xgwm275 | 2A | ns | 0.0959 | 0.125 | 0.110 |

| Xgwm261 | 2DS | 0.151 | 0.163 | 0.163 | 0.159 |

| Xbarc133 | 3B | 0.105 | 0.09 | 0.118 | 0.104 |

| Xbarc147 | 3B | 0.17 | ns | 0.117 | 0.144 |

| Xgwm533 | 3B | 0.108 | 0.068 | 0.089 | 0.088 |

| Xgwm160 | 4AL | 0.09 | 0.172 | 0.113 | 0.125 |

| Xcfa2040 | 1D,2D,7A,7B,7D | ns | 0.102 | 0.098 | 0.100 |

| Xwmc150 | 2A,3A,5A,5D,6A,7D | 0.072 | 0.095 | ns | 0.084 |

| Xwmc47 | 4BL,5A,5B | 0.092 | 0.084 | 0.08 | 0.085 |

| Xwmc273 | 7A,7B,7D | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.112 | 0.117 |

ns: non-significant at α = 0.05.

Three markers Xcfa2263, Xgwm249 and Xgwm275 on 2A were significant in two experiments (Supplemental Table 5). The genetic distances between Xgwm249 and Xgwm275, and between Xgwm249 and Xcfa2263 are 2.0 cM and 3.0 cM, respectively, on composite map (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov), suggesting these three markers linked to the same QTL. Three previously published QTL are located on chromosome 2A, with one from ‘Ning7840’, ‘NK93604’ or ‘Freedom’, the second from ‘Ning8026’, ‘Spark’, ‘Wangshuibai’ and ‘Rubens’, and the third from ‘Stoa’, ‘Arina’ and ‘Renan’ (Buerstmayr et al. 2009). These three QTLs were distinct from each other according to the meta-analysis (Liu et al. 2009). Searching for the closed linked markers to Xgwm275, Xgwm249 and Xcfa2263 in the GrainGenes database (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/) found that all the three markers are tightly linked to the markers Xgwm515, Xgwm328 and Xgwm425 that are associated with the QTL in ‘Ning8026’ and ‘Spark’, suggesting the QTL on 2A in this study may be the same as the one in ‘Ning8026’ and ‘Spark’.

Xgwm261-2DS was significantly associated with FHB resistance in all the three experiments (Supplemental Table 5). This marker was associated with FHB resistance QTL in ‘Sumai3’, ‘Alondra’, ‘Nyubai’, ‘Romanus’, ‘Biscay’, ‘Gamenya’ and ‘Wangshuibai’ (Buerstmayr et al. 2009, Handa et al. 2008, Jia et al. 2005, Liu et al. 2006, Shen et al. 2003). Therefore, the marker Xgwm261 is a useful marker for the QTL. Another QTL was reported to be at the proximal region of 2DS in ‘Wuhan11’, ‘CJ9306’ and ‘DH181’ (Buerstmayr et al. 2009), but it was not detected in the current study.

Xbarc133, Xbarc147 and Xgwm533 were significant in at least two experiments (Supplemental Table 5). Xbarc133 explained a larger proportion of phenotypic variation than Xbarc147 and Xgwm533 did, thus it can be a powerful marker for Fhb1. These three markers have been frequently reported to be associated with Fhb1 (Bernardo et al. 2012, Chen et al. 2006, Hao et al. 2012, Li et al. 2012, Liu et al. 2008), and extensively used in wheat breeding programs worldwide due to a relatively consistent major effect in different backgrounds and to an enhanced resistance when combining with other QTLs.

Xgwm160-4AL was significant in all three experiments (Supplemental Table 5). This marker was associated with FHB resistance only in ‘Arina’ (Buerstmayr et al. 2009, Paillard et al. 2004).

Xwmc150 was significant in two of the three experiments (Supplemental Table 5). This marker is assigned to six chromosomal locations. Xwmc47 was significant in all the three experiments, and explained an average of 8.5% of the phenotypic variation. Xwmc47 was assigned to three chromosomal locations (Table 1). Xcfa2040 also was detected in all three experiments and explained an average of 10.0% of the phenotypic variation. This marker was assigned to five chromosomal locations (Table 1). It was also associated with the QTL on 7E chromosome in Thinopyrum (Shen and Ohm 2007). Xwmc273 was detected in all the three experiments and explained an average of 11.7% of the phenotypic variation. This marker was assigned to all three chromosomes of group 7. This marker was associated with the QTL for FHB resistance on 7D for type 2 resistance in Chinese wheat landrace ‘Haiyanzhong’ (Li et al. 2011), and also associated with QTL for FHB resistance on 7E chromosome in Thinopyrum (Shen and Ohm 2007).

QTL repeatability was determined mainly by marker-trait associations over the experiments, and these markers can be used to identify linked QTLs for FHB resistance in breeding schemes. However, due to FHB phenotyping complexities, the significant QTLs/ markers may disagree with each other in different experiments or among different labs. In the current experiments, some closely linked markers that associated with known QTLs were significant in different experiments, for example, Xgwm11 and Xbarc80 were significant in 2011 and 2012, respectively, and these two markers were closely linked to the QTL on chromosome 1B; Xgwm526 and Xwmc332 were detected in 2011 and 2012, respectively, and they were associated with the QTL on chromosome 2B; Xwmc705 on 5A was significant in 2011, Xbarc56, Xgwm304, Xbarc117 and Xbarc186 on the same chromosome were significant in 2012, and all of these five markers are associated with a known QTL on 5A and closely linked to each other according to the published maps (Buerstmayr et al. 2009, Liu et al. 2009), thus they most likely represent the same QTL. Although these markers might be not as diagnostic as the markers in Table 1, these markers explaining the largest phenotypic variation could be used to select the linked QTL.

Allelic variation at significant markers and their associations with PSS

In bi-parental mapping populations, individual marker locus may have only two alleles, whereas more than two alleles per marker locus are very common in a breeding population consisting of diverse germplasms due to accumulation of historical recombination and mutation events. In the current study, each marker significant in at least two experiments has more than two alleles. When more than one reproducible marker within same region was detected, only the markers that were reproducible and/or explaining the largest phenotypic variation (R2) was used to represent the QTL, and the NAV of the alleles at this marker locus was calculated. In the case that one marker is significant in one experiment but other linked markers were detected in another experiment, we calculated the allelic values only for the marker with the largest R2. The alleles at the preferential markers were classified into resistant (R), susceptible (S) and neutral alleles (N) (Table 2 lists only effective alleles).

Table 2.

The effective alleles at the preferential markers in the three experiments (2011, 2012, and 2013)

| Marker | Allele | Obs | Frequency (%) | Effect | Mean PSS | Allele feature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | ||||||

| Xcfa2263 | 144 | 19 | 9.79 | ns | 0.12 | 0.042 | 0.56 | S |

| 156 | 22 | 11.34 | ns | 0.172 | 0.112 | 0.61 | S | |

| 158 | 23 | 11.86 | −0.163 | −0.211 | −0.174 | 0.30 | R | |

| Xwmc332 | 225 | 7 | 3.61 | −0.285 | −0.239 | ns | 0.25 | R |

| Xgwm261 | 202 | 7 | 3.61 | −0.357 | −0.276 | −0.278 | 0.17 | R |

| 208 | 58 | 29.90 | ns | 0.086 | 0.071 | 0.55 | S | |

| Xbarc133 | 111 | 22 | 11.34 | −0.128 | −0.143 | −0.124 | 0.35 | R |

| 132 | 10 | 5.15 | 0.256 | ns | 0.258 | 0.68 | S | |

| 136 | 5 | 2.58 | 0.289 | ns | 0.231 | 0.71 | S | |

| 140 | 57 | 29.38 | ns | 0.095 | 0.072 | 0.56 | S | |

| 142 | 55 | 28.35 | −0.17 | −0.174 | −0.172 | 0.31 | R | |

| Xgwm160 | 193 | 45 | 23.20 | −0.13 | −0.169 | −0.152 | 0.33 | R |

| 210 | 15 | 7.73 | −0.18 | −0.235 | ns | 0.3 | R | |

| 223 | 67 | 34.54 | 0.08 | 0.154 | 0.107 | 0.59 | S | |

| Xwmc705 | 151 | 14 | 7.22 | 0.154 | 0.132 | 0.145 | 0.62 | S |

| 157 | 15 | 7.73 | 0.238 | 0.177 | 0.191 | 0.68 | S | |

| 174 | 6 | 3.09 | −0.239 | −0.194 | ns | 0.29 | R | |

| 178 | 8 | 4.12 | ns | 0.193 | 0.174 | 0.65 | S | |

| 184 | 27 | 13.92 | ns | −0.153 | −0.106 | 0.36 | R | |

| 188 | 7 | 3.61 | −0.207 | −0.185 | −0.204 | 0.28 | R | |

| 192 | 12 | 6.19 | −0.260 | −0.161 | −0.200 | 0.27 | R | |

| Xgwm276 | 102 | 24 | 12.37 | −0.158 | −0.185 | −0.112 | 0.33 | R |

| 110 | 12 | 6.19 | −0.347 | −0.254 | −0.288 | 0.18 | R | |

| 112 | 6 | 3.09 | 0.232 | ns | 0.282 | 0.71 | S | |

| Xwmc273 | 200 | 18 | 9.28 | ns | 0.123 | 0.133 | 0.6 | S |

| 202 | 77 | 39.69 | ns | 0.088 | 0.1 | 0.56 | S | |

| 206 | 12 | 6.19 | 0.271 | 0.225 | ns | 0.68 | S | |

| 207 | 42 | 21.65 | −0.151 | −0.19 | −0.16 | 0.31 | R | |

| 208 | 27 | 13.92 | −0.246 | −0.169 | −0.219 | 0.27 | R | |

| Xcfa2040 | 261 | 18 | 9.28 | ns | 0.123 | 0.133 | 0.6 | S |

| 263 | 74 | 38.14 | ns | 0.089 | 0.096 | 0.56 | S | |

| 267 | 64 | 32.99 | −0.104 | −0.106 | −0.133 | 0.36 | R | |

| Xwmc150 | 285 | 8 | 4.12 | 0.281 | 0.194 | 0.192 | 0.7 | S |

| 290 | 21 | 10.82 | 0.184 | 0.279 | 0.127 | 0.67 | S | |

| Xwmc47 | 150 | 105 | 54.12 | 0.043 | 0.076 | 0.050 | 0.53 | S |

| 153 | 25 | 12.89 | −0.246 | −0.251 | −0.228 | 0.24 | R | |

R/the resistant allele; S/the susceptible allele; ns/ not significant.

The size of alleles in this Table were tailed with an extra adpator of 18 bp.

In total, 36 effective alleles (p < 0.05) at the 11 preferential marker loci were identified, with 17 favorable (i.e. resistant) alleles, and 19 unfavorable (susceptible) alleles (Table 2). Nine preferential markers (Xcfa2263, Xgwm261, Xbarc133, Xgwm160, Xwmc705, Xgwm276, Xwmc273, Xcfa2040, Xwmc47) carried both alleles for resistance and susceptibility. However, only two unfavorable alleles at Xwmc150 and only one favorable allele at Xwmc332 were identified. At least two favorable and two unfavorable alleles were at Xwmc705 on 5A, Xbarc133 on 3BS, and Xwmc273 with undetermined locations. Frequencies of favorable alleles per marker ranged from 3.09 % at Xwmc705 to 32.99% at Xcfa2040, and those of unfavorable alleles per marker ranged from 2.58 % at Xbarc133 to 54.12% at Xwmc47 (Table 2).

The number of favorable and unfavorable alleles at the 11 preferential marker loci varied among accessions (Table 3). Chinese landraces and Japanese accessions had higher frequencies of the favorable alleles at most of the reproducible marker loci than other sources. Chinese commercial varieties also had high frequencies of favorable alleles at Xbarc133, Xwmc273 and Xcfa2040, suggesting the favorable alleles at the three QTLs for FHB resistance might undergo strong positive selections during the historical breeding process. The top seven favorable alleles that presented in higher frequencies in this population than an average favorable allele frequency of 12.73% are (from high to low) Xcfa2040_267, Xbarc133_142, Xgwm160_193, Xgwm273_207/208, Xwmc705_184, and Xwmc47_153, suggesting the QTLs for FHB resistance probably experienced positively natural and/or artificial selections. The favorable allele Xcfa2040_267 presents in 64 accessions (33%) including 39 from China and 15 from Japan, and 11 from other countries. Xbarc133 was associated with Fhb1 on 3BS and two favorable alleles of Xbarc133_142 and Xbarc133_111 were identified. The Xbarc133_142 allele was identified in 55 accessions (28.4%), including 12 Chinese landraces (such as ‘Meiqianwu’, ‘Y155’, ‘Canlaomai’ and ‘Hongjianzi’, ‘Sanchahoh’), 17 Chinese commercial varieties (such as ‘Sumai3’, ‘Ning7840’, ‘Huai69-6’ and ‘Xiangnong3’, ‘Fu5114’), 21 Japanese accessions (such as ‘NobeokaBozu’ and ‘Shinchunaga’) and five other accessions (such as ‘Ernie’) (Supplemental Table 6). However, Xbarc133_111 presented in a high frequency in Chinese landraces but was not detected in Chinese commercial varieties, and it also presented in much lower frequencies in other sources (Supplemental Table 6), indicating this allele might undergo a negative selection and might be associated with inferior agronomical or yielding performances. It is also possible that landraces have not been used in commercial breeding because breeders focus on elite × elite crosses. Interestingly, ‘HFZ’, ‘Nyubai’, ‘Tokai66’ and ‘WSB’ in G3 have the favorable allele Xbarc133_111, whereas ‘Sumai3’ and ‘Ning7840’ in G1 have the favorable allele Xbarc133_142. Our results agree with Cuthbert et al. (2006) who reported that Fhb1 from ‘Nyubai’ was mapped to the same locus as that of Fhb1 derived from ‘Sumai3’ but with different allele sizes. The FHB favorable allele Xgwm160_210 shares a similar trend to Xbarc133_111 that present in a much higher frequency in the Chinese wheat landraces but was not detected in Chinese commercial varieties. The favorable alleles of Xgwm261_202 and Xcfa2263_158 present only in Chinese and Japanese accessions, suggesting that the QTL associated with the two alleles are most likely specific to Asian accessions. Frequencies lower than 10% of the seven favorable alleles Xwmc705_174, Xwmc705_188, Xwmc705_192, Xwmc332_225, Xgwm261_202, Xgwm276_110 and Xgwm160_210 were observed at five marker loci. It is also possible that these alleles might be associated with unfavorable agronomical or yielding performances, thus have been gradually eliminated during the modern breeding process.

Table 3.

The accessions from different sources that carry the favorable alleles at the preferential markers

| Marker | The favorable allele | Source | Number of carriers | Frequency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| China (landrace) | China (variety) | Japan | USA | others | ||||

| Xcfa2263 | 158 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 11.9 |

| Xwmc332 | 225 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3.6 |

| Xgwm261 | 202 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3.6 |

| Xbarc133 | 111 | 15 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 11.3 |

| 142 | 12 | 17 | 21 | 2 | 3 | 55 | 28.4 | |

| Xgwm160 | 210 | 11 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 7.7 |

| 193 | 16 | 9 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 45 | 23.2 | |

| Xwmc705 | 174 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3.1 |

| 184 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 27 | 14 | |

| 188 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3.6 | |

| 192 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 6.2 | |

| Xgwm276 | 102 | 15 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 24 | 12.4 |

| 110 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 6.2 | |

| 112 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3.1 | ||

| Xwmc273 | 208 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 26 | 13.4 |

| 207 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 42 | 21.6 | |

| Xcfa2040 | 267 | 18 | 21 | 15 | 7 | 4 | 64 | 33.0 |

| Xwmc47 | 153 | 16 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 14 |

The size of alleles in this Table were tailed an extra adpator of 18 bp.

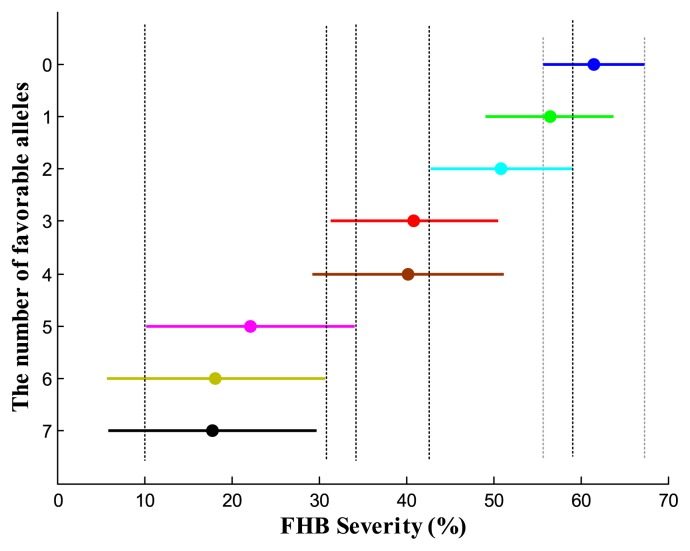

Based on seven important loci, altogether marked by 11 molecular markers, we classified 192 genotypes into eight groups (Fig. 3). The average PSS differed significantly among the eight groups (p = 6.27e−15). Mean PSSs increased as the number of favorable alleles decreased, and the accessions that carried seven favorable alleles without any of the unfavorable alleles had the lowest PSS, whereas the accessions carrying only the unfavorable alleles without any favorable alleles had the highest PSS, suggesting the significant markers identified here are reliable and the estimations of the allelic values are veritable. The genotype combinations with seven favorable alleles had significantly lower PSS than those combinations carrying 4 or fewer favorable alleles (Fig. 3). However, differences were not significant among combinations with 5 to 7 favorable alleles, nor among combinations with 1 to 3 favorable alleles. The accessions carrying 7 to 8 favorable alleles include nine Chinese landraces and nine Japanese accessions, and none of the unfavorable alleles were detected in these accessions (Supplemental Table 6). In total, 39 of 194 accessions from China and Japan do not have any of the identified unfavorable alleles, thus are valuable for FHB improvement in breeding. One hundred and fifty-five accessions have at least one unfavorable allele. Eighty-six accessions have both favorable and unfavorable alleles.

Fig. 3.

Comparisons of FHB severity (PSS) over the three seasons among the eight groups with different number of favorable alleles. The filled circle on the vertical line is the mean PSS of each group and the length of the line represents the confidence interval. Two groups not sharing a horizontal dashed line are significantly different at Turkey 0.05.

In summary, that most of the loci identified in this study confirmed previously published QTL and the negative correlations of PSS with number of favorable alleles of the significant FHB resistance markers indicates that the QTLs identified in this study are reliable and estimation of allelic values were convincing. However, the significant QTLs detected in this study were not exhaustive due to limited marker coverage. For those markers with multiple chromosomal locations, the chromosomal locations of the effective alleles remain to be decided in specifically designed populations derived from the cross of favorable and unfavorable donors.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support by the National Major Project of Breeding for New Transgenic Organisms (2012ZX08009003-004), NSFC (31171537), the Innovative Research Team of Universities in Jiangsu Province, and A Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Literature Cited

- Bai, G. and Shaner, G. (2004) Management and resistance in wheat and barley to Fusarium head blight. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 42: 135–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban, T., Kawad, N., Yanagisawag, A. and Takezaki, A. (2008) Progress and future prospects of resistance breeding to fusarium head blight in Japan. Cereal Res. Commun. 36: 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, A., Ma, H., Zhang, D. and Bai, G. (2012) Single nucleotide polymorphism in wheat chromosome region harboring Fhb1 for Fusarium head blight resistance. Mol. Breed. 29: 477–488. [Google Scholar]

- Buerstmayr, H., Ban, T. and Anderson, J.A. (2009) QTL mapping and marker-assisted selection for Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat: a review. Plant Breed. 128: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Griffey, C.A., Maroof, M.A.S., Stromberg, E.L., Biyashev, R.M., Zhao, W., Chappell, M.R., Pridgen, T.H., Dong, Y. and Zeng, Z. (2006) Validation of two major quantitative trait loci for fusarium head blight resistance in Chinese wheat line W14. Plant Breed. 125: 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert, P.A., Somers, D.J., Thomas, J., Cloutier, S. and Brule-Babel, A. (2006) Fine mapping Fhb1, a major gene controlling fusarium head blight resistance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 1465–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami, F., Elias, E.M., Mamidi, S., Ansari, O., Sargolzaei, M., Adhikari, T., Mergoum, M. and Kianian, S.F. (2011) Mixed model association mapping for Fusarium head blight resistance in Tunisian-derived durum wheat populations. G3 (Bethesda) 1: 209–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häberle, J., Holzapfel, J., Schweizer, G. and Hartl, L. (2009) A major QTL for resistance against Fusarium head blight in European winter wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119: 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D., Tegstrom, C. and Ingvarsson, P.K. (2010) Using association mapping to dissect the genetic basis of complex traits in plants. Brief Funct. Genomics 9: 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa, H., Namiki, N., Xu, D. and Ban, T. (2008) Dissecting of the FHB resistance QTL on the short arm of wheat chromosome 2D using a comparative genomic approach: from QTL to candidate gene. Mol. Breed. 22: 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, C., Wang, Y., Hou, J., Feuillet, C., Balfourier, F. and Zhang, X. (2012) Association mapping and haplotype analysis of a 3.1-mb genomic region involved in Fusarium head blight resistance on wheat chromosome 3BS. Plos ONE 7: 046444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayatilake, D.V., Bai, G.H. and Dong, Y.H. (2011) A novel quantitative trait locus for Fusarium head blight resistance in chromosome 7A of wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122: 1189–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, G., Chen, P., Qin, G., Bai, G., Wang, X., Wang, S., Zhou, B., Zhang, S. and Liu, D. (2005) QTLs for Fusarium head blight response in a wheat DH population of Wangshuibai/Alondra‘s’. Euphytica 146: 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kollers, S., Rodemann, B., Ling, J., Korzun, V., Ebmeyer, E., Argillier, O., Hinze, M., Plieske, J., Kulosa, D., Ganal, M.W.et al. (2013) Whole genome association mapping of Fusarium head blight resistance in European winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plos ONE 8: 057500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, T., Bai, G., Wu, S. and Gu, S. (2011) Quantitative trait loci for resistance to fusarium head blight in a Chinese wheat landrace Haiyanzhong. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122: 1497–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, T., Bai, G.H., Wu, S.Y. and Gu, S.L. (2012) Quantitative trait loci for resistance to Fusarium head blight in the Chinese wheat landrace Huangfangzhu. Euphytica 185: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F., Xue, S.L., Zhang, Z.Z., Zhang, C.Q., Kong, Z.X., Yao, G.Q., Tian, D.G., Zhu, H.L., Li, C.J., Cao, Y.et al. (2006) Mapping QTL associated with resistance to Fusarium head blight in the Nanda2419 × Wangshuibai population. II: type I resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 528–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.J. and Muse, S.V. (2005) PowerMarker: an integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics 21: 2128–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S., Zhang, X., Pumphrey, M., Stack, R., Gill, B. and Anderson, J. (2006) Complex microcolinearity among wheat, rice, and barley revealed by fine mapping of the genomic region harboring a major QTL for resistance to Fusarium head blight in wheat. Funct. Integr. Genomics 6: 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S., Pumphrey, M.O., Gill, B.S., Trick, H.N., Zhang, J.X., Dolezel, J., Chalhoub, B. and Anderson, J.A. (2008) Toward positional cloning of Fhb1, a major QTL for Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Cereal Res. Commun. 36: 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S., Hall, M.D., Griffey, C.A. and McKendry, A.L. (2009) Meta-analysis of QTL associated with Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Crop Sci. 49: 1955–1968. [Google Scholar]

- Löffler, M., Schön, C.-C. and Miedaner, T. (2009) Revealing the genetic architecture of FHB resistance in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by QTL meta-analysis. Mol. Breed. 23: 473–488. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, T., Collins, G. and Sedgley, M. (1994) A modified CTAB DNA extraction procedure for plants belonging to the family proteaceae. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 12: 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- Massman, J., Cooper, B., Horsley, R., Neate, S., Dill-Macky, R., Chao, S., Dong, Y., Schwarz, P., Muehlbauer, G.J. and Smith, K.P. (2011) Genome-wide association mapping of Fusarium head blight resistance in contemporary barley breeding germplasm. Mol. Breed. 27: 439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Miedaner, T., Würschum, T., Maurer, H.P., Korzun, V., Ebmeyer, E. and Reif, J.C. (2011) Association mapping for Fusarium head blight resistance in European soft winter wheat. Mol. Breed. 28: 647–655. [Google Scholar]

- Navara, S. and Smith, K.P. (2014) Using near-isogenic barley lines to validate deoxynivalenol (DON) QTL previously identified through association analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 127: 633–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillard, S., Schnurbusch, T., Tiwari, R., Messmer, M., Winzeler, M., Keller, B. and Schachermayr, G. (2004) QTL analysis of resistance to Fusarium head blight in Swiss winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 109: 323–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X., Zhou, M., Lu, W. and Ohm, H. (2003) Detection of Fusarium head blight resistance QTL in a wheat population using bulked segregant analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106: 1041–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X. and Ohm, H. (2007) Molecular mapping of Thinopyrum-derived Fusarium head blight resistance in common wheat. Mol. Breed. 20: 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Q., Liu, X., Liu, Z., Wang, C. and Ji, W. (2009) SSR analysis of Funo wheat and its derivatives. Acta Agronomica Sinica 35: 615–619. [Google Scholar]

- Trail, F. (2009) For blighted waves of grain: Fusarium graminearum in the postgenomics era. Plant Physiol. 149: 103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.B., Bai, G.H., Cai, S.B. and Ban, T. (2006) Marker-assisted characterization of Asian wheat lines for resistance to Fusarium head blight. Theor. Appl. Genet. 113: 308–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.B., Bai, G.H., Zhou, W.C., Dong, Y.H. and Kolb, F.L. (2008) Quantitative trait loci for Fusarium head blight resistance in a recombinant inbred population of Wangshuibai/Wheaton. Phytopathology 98: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.M., Pressoir, G., Briggs, W.H., Bi, I.V., Yamasaki, M., Doebley, J.F., McMullen, M.D., Gaut, B.S., Nielsen, D.M., Holland, J.B.et al. (2006) A unified mixed-model method for association mapping that accounts for multiple levels of relatedness. Nat. Genet. 38: 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J. and Jiang, Y. (2013) The causal factors for the epidemics of wheat Fusarium head blight in the year of 2012 in China and the strategies for continuous monitoring and prevention. China Plant Protection 33: 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Pan, H. and Bai, G. (2012) Quantitative trait loci responsible for Fusarium head blight resistance in Chinese landrace Baishanyuehuang. Theor. Appl. Genet. 125: 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.