Abstract

Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome is a rare but fatal disease, which occurs commonly in immunocompromised patients. Strongyloidiasis among patients with chronic kidney disease is rarely reported.

A 55-year-old Chinese male presented to hospital with diarrhea and abdominal pain. He developed acute respiratory failure and progressed to diffuse alveolar hemorrhage owing to disseminated strongyloidiasis immediately. The bronchoalveolar lavage revealed filariform larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis.

This patient was diagnosed with Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome. Although albendazole, mechanical ventilator support, fluid resuscitation, vasopressor support, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, hydrocortisone, and broadspectrum antimicrobials were actively used, the patient eventually died.

Similar cases in patients with chronic kidney disease in the literature are also reviewed. Through literature review, we recommend that strongyloidiasis should be routinely investigated in patients with chronic kidney disease who will undergo immunosuppressive therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Strongyloides stercoralis (S stercoralis) is a parasite that is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions and occurs sporadically in temperate areas.1,2 Adult worms live in the host's small intestine, such as humans, dogs, cats, etc. The larvae can invade the lung, brain, liver, and kidney, as well as other tissues or organs, causing strongyloidiasis. The clinical presentation of strongyloidiasis varies from asymptomatic infection and mild symptomatic abdominal disease to fatal disseminated infection in immunosuppressed patients.3,4 Pulmonary strongyloidiasis is one of the most important signs of disseminated strongyloidiasis.

Corticosteroids are commonly used for chronic kidney diseases. However, steroids also cause immunosuppression, which could be life-threatening in patients infected with S stercoralis seen in worldwide. We report a fatal case of S stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome in a patient with chronic kidney disease and review the literatures of S stercoralis infections in patients with kidney disease.

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old man had a 3-week history of diarrhea, 1-week history of cough, expectoration, and shortness of breath after activity. Two days before, he presented with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, accompanied by fever. The patient is a farmer who was originated from a rural area in Zhejiang Province, China. He used to work barefoot in the farm. A low-dose of oral methylprednisolone (25 mg/day) and Tripterygium wilfordii (TwHF) therapy had been initiated for chronic kidney disease (nephrotic syndrome) 2 months before presentation.

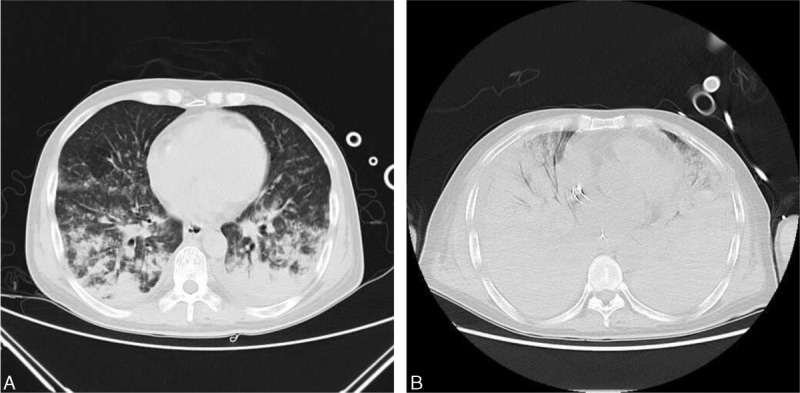

On arrival to the emergency ICU, he was found to be hypotensive and hypoxemic. His temperature was 38.6°C, blood pressure was 78/35 mmHg, and arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) was 63.7 mmHg. He was given a preliminary diagnosis of septic shock from abdominal source, and acute respiratory failure. Mechanical ventilation, aggressive volume resuscitation, and vasopressor support were rapidly used. Piperacillin/tazobactam was administered for empirical anti-infection treatment. His computed tomographic scan of the chest revealed widespread bilateral infiltrates surrounded by ground-glass opacification (Figure 1A). His computed tomographic scan of the abdomen revealed peripancreatic, peritoneal effusion, ascites, and the stomach diffuse edema. On admission, the patient's blood cultures were negative. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative and the CD4+ count was normal. He had an increased C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 118 (normal, <10) mg/L, a white blood cell imaging count of 12.4 (normal, 4.0–10.0) × 109 cells/L, and a neutrophil percentage of 91.8% (normal, 50%–70%). His eosinophil count was zero. Coagulation-related tests, hemoglobin (Hb) concentration, his platelet count, and Hb concentration were normal. His creatinine concentration (157 μmol/L) had been above the “normal range” (50–120 μmol/L) (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Computed tomography of the chest with contrast. (A) Computed tomography of the chest on day 1 of admission. It revealed widespread bilateral infiltrates surrounded by ground-glass opacification. (B) Computed tomography of the chest on day 4 of admission. It revealed extensive bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, which was worse than the first day.

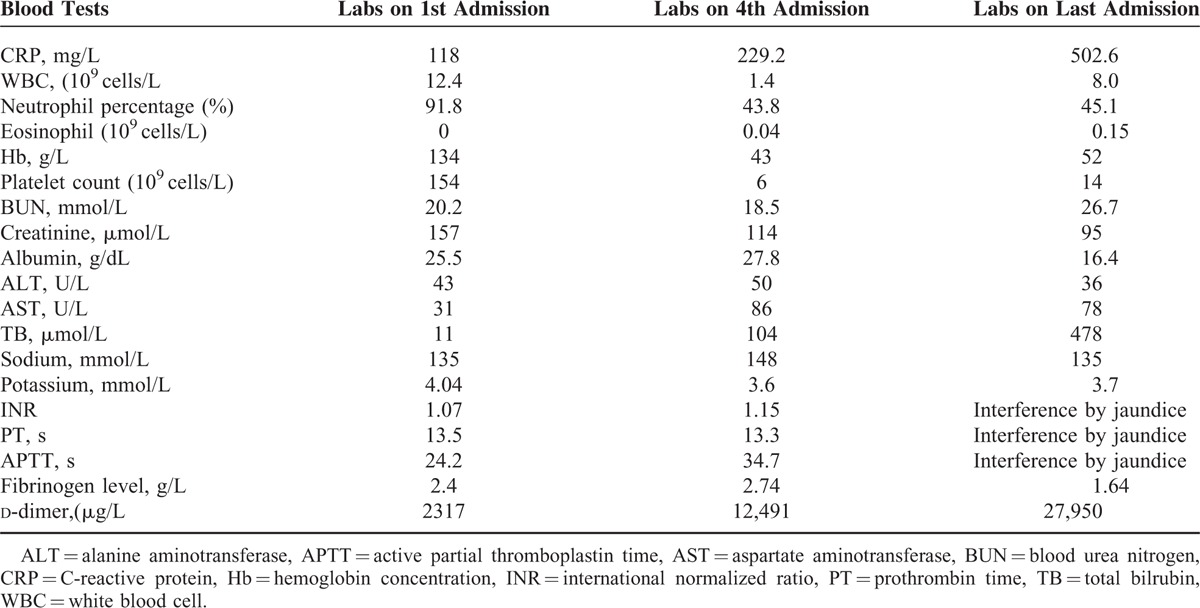

TABLE 1.

Results of Blood Tests

On day 4 of admission, laboratory results revealed that white blood cell count was reduced to 1.4 (normal, 4.0–10.0) × 109 cells/L (43.8% neutrophils), Hb concentration was 43 g/L, and the platelet count was 6 (normal, 83–303) × 109 cells/L. CRP level increased to 229.2 (normal, <10) mg/L. Total bilrubin increased to 104 μmol/L. The results of blood tests were shown in Table 1. A computed tomography scan of the chest revealed extensive bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, which was worse than the first day (Figure 1B). The computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed small bowel wall thickening and ascites. His level of consciousness was reduced, with ecchymosis in large area of trunk limbs.

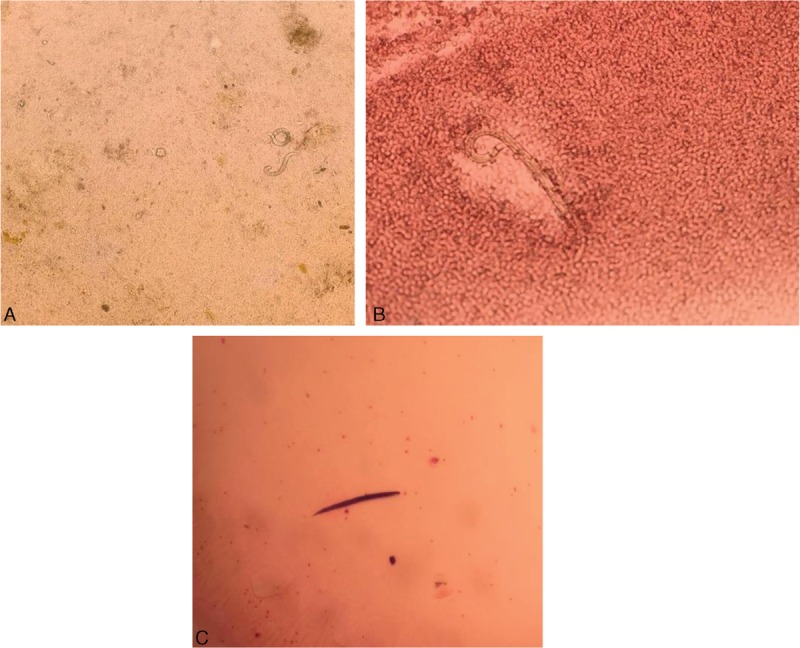

A stool specimen revealed the presence of Strongyloides (Figure 2A). A flexible bronchoscopy was performed on day 2 of admission. The bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) showed severe diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). The BAL revealed filariform larvae of S stercoralis (Figure 2B and Figure 2C). The remaining stains for fungi were negative. The cytology from the BAL also did not reveal any malignant cells. The results of blood and sputum cultures were negative. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with disseminated S stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome resulting in severe DAH.

FIGURE 2.

Strongyloides stercoralis under the microscope. (A) Strongyloides stercoralis larva in stool sample. (B) Strongyloides stercoralis larva in the bronchoalveolar lavage. (C) Strongyloides stercoralis larva Gram stain.

The patient was given albendazole (400 mg/day) on day 2 of admission because ivermectin is not available in our country. The patient continued to be in severe hypoxic and respiratory failure without improvement. Although mechanical ventilator support, fluid resuscitation, vasopressor support, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, hydrocortisone, and broadspectrum antimicrobials were also actively used, he eventually developed cardiac arrest and expired after 1 week. The results of blood tests on the last day admission are presented in Table 1.

We obtained an exempt status from the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University to use these data.

DISCUSSION

Infection with S stercoralis is a significant global public health problem. Worldwide, S stercoralis infects 30 to 100 million people in 70 countries.5–7 In China, Zhejiang Province belongs to a subtropical monsoon zone. However, strongyloidiasis has rarely been reported in Zhejiang Province. Infection usually results in asymptomatic chronic disease of the gut, which can remain undetected for decades. This can also lead to polymicrobial bacteremia, gram-negative bacillary meningitis, pneumonitis, and alveolar hemorrhage. However, hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease usually develop as a result of immune suppression caused by HIV infection, in addition to immunocompromised states like administration of corticosteroids, tumor necrosis factor-αantagonists, or transplantation.4 When immunosupression develops, autoinfection accelerates and hyperinfection occurs. Major complaints were fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, abdominal distension, weight loss, vomiting, cough, anemia, hemoptysis. It is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The mortality rate for disseminated strongyloidiasis is as high as 77% among compromised hosts.1,8 In patients receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy, hyperinfection can occur, resulting in high mortality rates (up to 87%).9 Our patient had oral administration of corticosteroids because of chronic kidney disease for 2 months. Early detection of strongyloidiasis in such individuals is extremely important, as hyperinfection is potentially fatal.

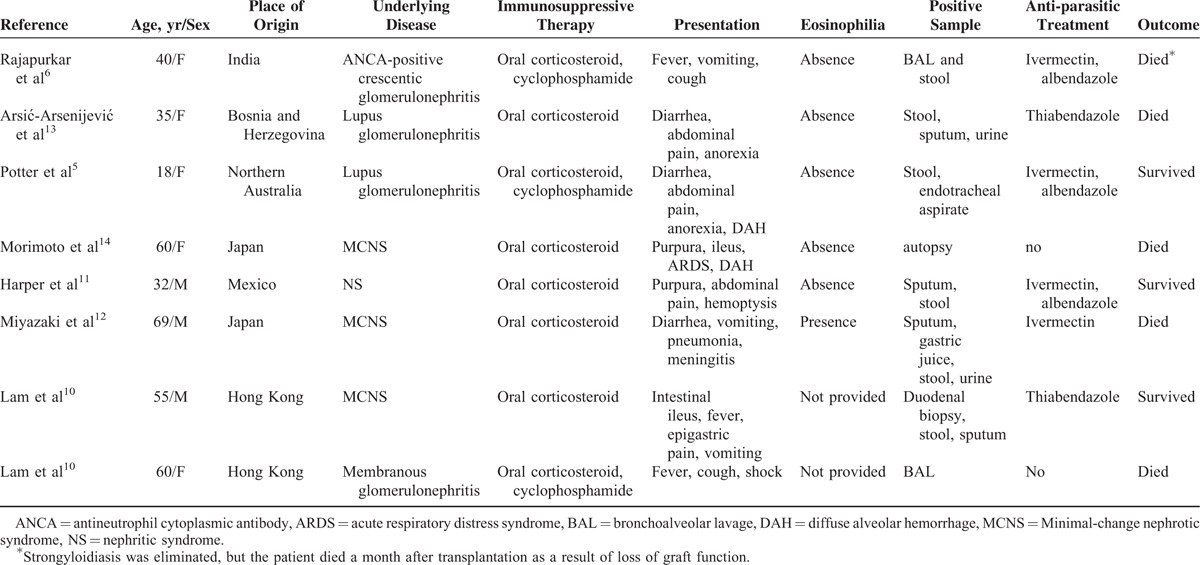

Strongyloidiasis among patients with chronic kidney disease is rarely reported. We performed a literature search using the terms “Strongyloides stercoralis AND kidney disease,” “Strongyloides stercoralis AND renal disease,” “Strongyloides stercoralis ND nephropathy,” “Strongyloides stercoralis AND nephrotic syndrome,” and “Strongyloides stercoralis AND renal failure” on PubMed. Articles in English were included. Transplant or HIV patients were excluded. In some articles dealing with strongyloidiasis cases with kidney involvement, acute nephritis was the presentation of strongyloidiasis and this renal injury might be brought on by severe infection of S stercoralis. These articles were also excluded. Only reports on strongyloidiasis in patients with kidney disease including the main clinical and biological data and the survival status were taken into account. In total, 7 studies (8 cases) met the inclusion criteria describing S stercoralis infection in patients with kidney disease (Table 2).5,6,10–14 All of the 8 patients have oral corticosteroids to treat kidney disease before S stercoralis infection. The use of corticosteroids is the important risk factor of strongyloidiasis. Among these 8 cases in the medical literature, 7 cases were of hyperinfection, of which 4 cases have reported fatal outcomes because of strongyloidiasis (Table 2). In most cases, in the literature, primary complaints were occasionally evaluated as different diagnosis than strongyloidiasis; but, after that duodenal biopsy, BAL, stool and sputum samples showed the parasite. Especially in Morimoto et al and Larn et al's reports, the patients were made the definite diagnosis after death. In our case, the patient has been on low-dose steroid therapy and finally died of the S stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome complicated by DAH. To avoid fatal outcomes because of strongyloidiasis, routine investigation and early treatment of strongyloidiasis in patients with chronic kidney disease who will undergo immunosuppressive therapy is necessary.

TABLE 2.

Reported Cases of Strongyloides stercoralis Infection in Patients With Kidney Disease

The diagnosis of hyperinfection and disseminated disease is usually established by examining stool as well as other normally sterile sites for filariform or rhabditiform larvae.15,16 Because the parasite load is low and the larval output is irregular, strongyloidiasis is difficult to diagnose. Up to 70% of cases were failed to be diagnosed according to a single stool examination by use of conventional techniques.9,17 However, immunodiagnostic assays always show extensive cross-reactivity with other parasites such as hookworms, filariae, and schistosomes. For early detection of S stercoralis infection, further research is necessary.

The larvae of S stercoralis that were found in the patient's BALF and feces provide diagnostic proof of disseminated strongyloidiasis; however, the decreased eosinophil count remained elusive because most parasitic diseases are accompanied by an increased number of eosinophils. Boulware et al reported that about 84% of strongyloidiasis cases have an eosinophil percentage of >5%.1,18 The other patients, especially immunocompromised patients with disseminated strongyloidiasis who have a secondary response to S stercoralis, may have a normal or reduced eosinophil count, as this case did. Eosinophils and neutrophils contribute to larval killing during the primary immune response, and neutrophils are effector cells in the secondary response to S stercoralis.19,20 Thus, we also highlight that a normal or reduced eosinophil count does not exclude a parasitic infection.

We considered there were 2 main reasons of the treatment failure in this case. First, delay in diagnosis reduces the therapy efficacy and leads to treatment failure. Second, in hyperinfection cases, ileus and small-bowel obstruction may prevent enteral absorption of anthelminthics. Ivermectin and albendazole are the first-line treatments only for uncomplicated infection.21 The optimal therapeutic approach remains uncertain in hyperinfection cases. The mortality rate of hyperinfection is likely to be around 100% without effective treatment.22 The published experience of parenteral ivermectin use was limited.22 More data are needed to guide dosing schedules and monitoring for toxicity.

CONCLUSIONS

Owing to increased risk of developing disseminated disease or hyperinfection syndrome, early detection and treatment of strongyloidiasis are extremely important. A high level of clinical suspicion is required to make the diagnosis of strongyloidiasis in at-risk patients presenting with diarrhea, acute or subacute cough, wheezing, or alveolar hemorrhage. Strongyloidiasis should be routinely investigated in patients with chronic kidney disease who will undergo immunosuppressive therapy.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ALT = alanine aminotransferase, ANCA = antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, APTT = active partial thromboplastin time, ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, AST = aspartate aminotransferase, BAL = bronchoalveolar lavage, BUN = blood urea nitrogen, CRP = C-reactive protein, DAH = diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, Hb = hemoglobin concentration, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, INR = international normalized ratio, MCNS = Minimal-change nephrotic syndrome, NS = nephritic syndrome, PT = prothrombin time, S stercoralis = Strongyloides stercoralis, TB = total bilrubin, TwHF = Tripterygium wilfordii, WBC = white blood cell.

T-TQ and QY contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by the research grant from the National Natural Science Foundations of China (No.NSFC81371859).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guo J, Sun Y, Man Y, et al. Coinfection of Strongyloides stercoralis and Aspergillus found in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from a patient with stubborn pulmonary symptoms. J Thorac Dis 2015; 7:E43–E46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.M.O J, Gracia S, Villoria F, et al. Disseminated strongyloidiasis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Eur J Intern Med 2004; 15:529–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uparanukraw P, Phongsri S, Morakote N. Fluctuations of larval excretion in Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999; 60:967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004; 17:208–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potter A, Stephens D, De Keulenaer B. Strongyloides hyper-infection: a case for awareness. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2003; 97:855–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajapurkar M, Hegde U, Rokhade M, et al. Respiratory hyperinfection with Strongyloides stercoralis in a patient with renal failure. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2007; 3:573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geri G, Rabbat A, Mayaux J, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome: a case series and a review of the literature. Infection 2015; 43:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Namisato S, Motomura K, Haranaga S, et al. Pulmonary strongyloidiasis in a patient receiving prednisolone therapy–. Intern Med (Tokyo, Japan) 2004; 43:731–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam CS, Tong MK, Chan KM, et al. Disseminated strongyloidiasis: a retrospective study of clinical course and outcome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2006; 25:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper G, Ong JL. Anasarca, renal failure, hemoptysis, and rash in a 32-year-old male Mexican immigrant. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:601–602.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyazaki M, Tamura M, Kabashima N, et al. Minimal change nephrotic syndrome in a patient with strongyloidiasis. Clin Exp Nephrol 2010; 14:367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arsic-Arsenijevic V, Dzamic A, Dzamic Z, et al. Fatal Strongyloides stercoralis infection in a young woman with lupus glomerulonephritis. J Nephrol 2005; 18:787–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morimoto J, Kaneoka H, Sasatomi Y, et al. Disseminated strongyloidiasis in nephrotic syndrome. Clin Nephrol 2002; 57:398–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segarra-Newnham M. Manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Ann Pharmacother 2007; 41:1992–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayaprakash B, Sandhya S, Anithakumari K. Pulmonary strongyloidiasis. J Assoc Physicians India 2009; 57:535–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montes M, Sawhney C, Barros N. Strongyloides stercoralis: there but not seen. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2010; 23:500–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boulware DR, Stauffer WM, Hendel-Paterson BR, et al. Maltreatment of Strongyloides infection: case series and worldwide physicians-in-training survey. Am J Med 2007; 120:e541–e548.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Connell AE, Hess JA, Santiago GA, et al. Major basic protein from eosinophils and myeloperoxidase from neutrophils are required for protective immunity to Strongyloides stercoralis in mice. Infect Immun 2011; 79:2770–2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galioto AM, Hess JA, Nolan TJ, et al. Role of eosinophils and neutrophils in innate and adaptive protective immunity to larval strongyloides stercoralis in mice. Infect Immun 2006; 74:5730–5738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Datry A, Hilmarsdottir I, Mayorga-Sagastume R, et al. Treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis infection with ivermectin compared with albendazole: results of an open study of 60 cases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1994; 88:344–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrett J, Broderick C, Soulsby H, et al. Subcutaneous ivermectin use in the treatment of severe Strongyloides stercoralis infection: two case reports and a discussion of the literature. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 86:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]