Abstract

Primary urethral carcinoma (PUC) is a rare and aggressive cancer, often underdetected and consequently unsatisfactorily treated. We report a case of advanced PUC, surgically treated with combined approaches.

A 47-year-old man underwent transurethral resection of a urethral lesion with histological evidence of a poorly differentiated squamous cancer of the bulbomembranous urethra. Computed tomography (CT) and bone scans excluded metastatic spread of the disease but showed involvement of both corpora cavernosa (cT3N0M0). A radical surgical approach was advised, but the patient refused this and opted for chemotherapy. After 17 months the patient was referred to our department due to the evidence of a fistula in the scrotal area. CT scan showed bilateral metastatic disease in the inguinal, external iliac, and obturator lymph nodes as well as the involvement of both corpora cavernosa. Additionally, a fistula originating from the right corpus cavernosum extended to the scrotal skin. At this stage, the patient accepted the surgical treatment, consisting of different phases. Phase I: Radical extraperitoneal cystoprostatectomy with iliac-obturator lymph nodes dissection. Phase II: Creation of a urinary diversion through a Bricker ileal conduit. Phase III: Repositioning of the patient in lithotomic position for an overturned Y skin incision, total penectomy, fistula excision, and “en bloc” removal of surgical specimens including the bladder, through the perineal breach. Phase IV: Right inguinal lymphadenectomy.

The procedure lasted 9-and-a-half hours, was complication-free, and intraoperative blood loss was 600 mL. The patient was discharged 8 days after surgery. Pathological examination documented a T4N2M0 tumor. The clinical situation was stable during the first 3 months postoperatively but then metastatic spread occurred, not responsive to adjuvant chemotherapy, which led to the patient's death 6 months after surgery.

Patients with advanced stage tumors of the bulbomembranous urethra should be managed with radical surgery including the corporas up to the ischiatic tuberosity attachment, and membranous urethra in continuity with the prostate and bladder. Neo-adjuvant treatment may be advisable with the aim of improving the poor prognosis, even if the efficacy is not certain while it can delay the radical treatment of the disease.

INTRODUCTION

The urethra is frequently involved in other genitourinary tumors as a secondary site, in both males and females. Primary urethral carcinoma (PUC) is a rare and aggressive cancer, often underdetected and consequently unsatisfactorily treated. The incidence in men is 1.6 cases per million in Europe and nearly 3 times higher in the United States. The median age at diagnosis is about 60 years in both genders, the age-standardized rate for ages <55 years being negligible (0.2 per million).1–3 A recent Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) analysis of 2065 males treated for PUC between 1988 and 2006 showed that at presentation 23% and 22% of patients had invasive disease and nodal involvement, respectively.4 Histologically, the most frequent subtype is transitional cell cancer (77.6%), followed by squamous cell neoplasm (11.9%) and adenocarcinoma (5%).3,4 In men, 59% of cancers affect the bulbomembranous urethra, while anterior and prostatic urethra account for 33% and 7%, respectively.5,6 Treatment depends on the stage and location of the tumor: while low stage cancers of the distal urethra may be treated with preserving surgery, in cases of higher stage tumors of the bulbomembranous urethra a radical approach is indicated, together with a chemo/radiotherapeutic regimen.7,8 Distal cancers of the male urethra exhibit significantly improved survival rates compared with proximal tumors, and present a cure rate which can reach 90% thanks to a generally earlier detection referable to more evident symptoms.7,9 Instead, proximal neoplasms are usually invasive and more aggressive at presentation and require extended surgery including resection of the penis, urethra, scrotum, and pubic bone with radical cystoprostatectomy. Disease-free survival (DFS) for these patients is reported to be between 33% and 45%.5,10,11

Cystoprostatectomy and penectomy can be performed through an exclusively prepubic incision or through a combined procedure that also includes a perineal approach.12 We report our experience of surgical management, through a prepubic and perineal approach, of a case of invasive squamous carcinoma of the bulbomembranous urethra.

Case Report

A 47-year-old man underwent, for the first time, urological assessment in 2009 for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and urethral bleeding lasting 2 months. Initially he underwent bladder ultrasound which resulted negative, and urinary cytology which raised suspicion. Urethrocystoscopy revealed a solid lesion, red and friable, of the bulbomembranous urethra, with a major extension of 3 cm in diameter. The prostatic urethra and bladder were lesion-free. The patient underwent transurethral resection of the urethral lesion, showing histological evidence of a poorly differentiated squamous cancer of the bulbomembranous urethra, with invasion of the superficial muscle layer but not vascular structures related to the corpus cavernosum. Computed tomography (CT) and bone scans excluded metastatic spread of the disease but showed the involvement of both corpora cavernosa, delineating a cT3N0M0 tumor. A radical surgical approach was advised, consisting of cystoprostatectomy and penectomy with local lymph node dissection. This treatment was declined by the patient and, after oncological counseling, a chemotherapeutic regimen based on 5-fluorouracyl (5-FU) and Cisplatin was started. Radiotherapy was not recommended by the oncologist, at this stage of the disease.

After 17 months follow-up without any evidence of disease progression, at the last imaging investigation the patient was referred to our department due to the evidence of a fistula in the scrotal area and a tough thickening of the penile shaft (Figure 1A and B). At the physical examination, enlargement of the lymph nodes in both groins was evident. CT scan showed bilateral metastatic disease in the inguinal, external iliac, and obturator lymph nodes, as well as the involvement of both corpora cavernosa (Figure 2A). Additionally, a fistula originating from the right corpus cavernosum extended—through a perineal collection with a maximum diameter of 4.5 cm and including several calcifications—to the scrotal skin (Figure 2B). Cystoprostatectomy, penectomy with iliac-obturator and inguinal lymph nodes dissection was suggested. At this stage of the disease, the patient accepted the suggested treatment.

FIGURE 1.

Fistula originating from the right corpus cavernosum was extended to the scrotal skin (A); infected wound with drainage of purulent material (B).

FIGURE 2.

Computed tomography scan evidence of bilateral metastatic disease in the inguinal, external iliac, and obturator lymph nodes with the involvement of both corpora cavernosa (A and B).

Written informed consent was given by the patient. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of University of Bari and conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki in 1995.

Surgical Procedure

Bowel preparation was done 18 h preoperatively, and low molecular weight heparin (0.4 mL/d) was administered as from 12 h before the procedure. The operation was performed under general anesthesia with preoperative placement of an epidural catheter, left in situ for 48 h to reduce postoperative pain.

The whole procedure was carried out by means of a double surgical approach using LigaSure 15 mm (Valleylab, Boulder, CO) and the UltraCision Harmonic Scalpel (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH) for sharp and blunt dissection. The surgical procedure consisted of different phases (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Skin incisions made during the surgical procedure.

Phase I: The first step, performed with the patient in supine position, consisted of radical extraperitoneal cystoprostatectomy with prior iliac-obturator lymph nodes dissection via a pubic-umbilical incision. The bladder was isolated and its peduncles were tied while the blunt and sharp dissection proceeded toward the bulbomembranous urethra following the previously positioned 24 Foley catheter. The proximal urethra was isolated around its circumference and dissected from the pelvic floor and the prepubic area, leaving a thin layer of urogenital diaphragm attached, but it was not sectioned in order to preserve its continuity with the penile urethra and to avoid cancer cells spillage. Phase II: At the end of this first demolitive step, urinary diversion through a Bricker ileal conduit was performed using a 15-cm section of distal ileum. Ureteroileal anastomosis was created according to the Wallace technique. In particular, we preferred a head-to-tail type anastomosis performed by suturing the apex of 1 ureter to the end of the other. The posterior medial walls were sewn together, and then the ends and lateral walls were sewn to the ileum.

The ileal conduit was completely extraperitonealized, and an omental flap was isolated for reconstruction of the perineal defect after the second demolitive phase. The isolated specimen composed of the bladder and the proximal mobilized urethra was left in situ and the abdominal wall was closed.

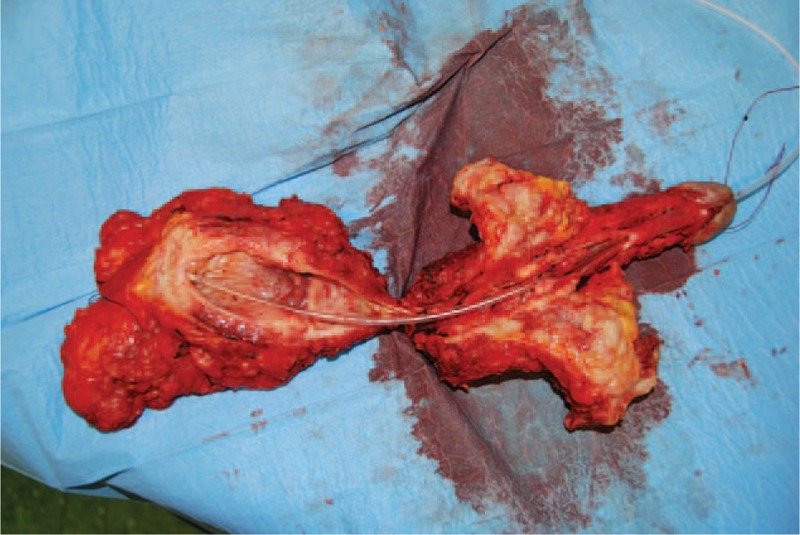

Phase III: The next part of the procedure started with repositioning of the patient in lithotomic position to achieve complete exposure of the perineal plane. A cutaneous overturned Y incision was made along the ventral side of the penile shaft from its tip to the ischial tuberosity projection on the perineal skin. The incision included the skin with the neoplastic fistula. The dartoic layer was dissected, exposing the corporas, penile urethra, and both testes with the spermatic cords. The latter structures were preserved, while the blunt and sharp dissection proceeded through the superficial toward the deep perineal space: the penile corporas were isolated dorsally to the crus and the bulbomembranous urethra was dissected from the rectum below. The neoplastic fistula was followed from the skin to its origin in the right corpus cavernosum and completely removed. The incision of the deeper layer proceeded along the proximal urethra toward the urogenital diaphragm, drawn back to expose the pelvis, and the whole specimen isolated during the first phase of the procedure was then removed “en bloc” through the perineal breach (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Whole specimen including the bladder, the prostate, the penis, and the fistula was removed “en bloc” through the perineal incision.

The wound was closed layer by layer starting from the deep perineal space and approaching the elevator ani and deep perineal transverse muscles. Aspiration drainage was positioned in the superficial perineal space, which was closed by suturing the Colles fascia on top. To strengthen the perineal area, the omental flap was attached to the pelvis through the abdominal incision before closure. At the end of the perineal phase, the skin was sutured with interrupted 3/0 Vicryl and the medial part of the scrotum was resurfaced using a penile skin flap that had previously been isolated and preserved from the shaft.

Phase IV: In this case, the patient had clinically enlarged right inguinal lymph nodes, so regional lymphadenectomy was performed through a vertical skin incision at the inguinal crease.

The whole procedure lasted 9-and-a-half hours, and was complication-free, with an intraoperative blood loss of 600 mL. The patient was discharged 8 days after surgery and postoperatively only a mild dehiscence of the perineal wound occurred, treated with local paraffin gauze dressing, resulting in complete healing within 3 weeks (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Perineal wound and the aspect of the scrotum resurfaced in its medial part with a penile skin flap, 3 wk postoperatively.

Pathological examination documented a poorly differentiated squamous cancer of the bulbomembranous and penile urethra with local invasion of the corpus spongiosum and both corpora cavernosa. The disease also involved the soft tissues of the penile shaft up to the reticularis derma, and 6 lymph nodes (T4N2M0).

The clinical situation was stable during the first 3 months postoperatively but then systemic metastatic spread of the disease occurred, not responsive to adjuvant chemotherapy based on the Methotrexate, Vinblastine, Doxorubicine, Cisplatin (MVAC) regimen, which led to the patient's death 6 months after surgery, 23 months after the onset of the first symptoms.

DISCUSSION

PUCs are rare diseases which account for only 1% of all male malignancies.2,3 The main predisposing factors in male urethral cancer are chronic inflammation, urethral stricture, radiotherapy, and urethritis in sexually transmitted diseases.7,13,14 In proximal urethral cancers, the signs are not always pathognomonic, because they can mimic LUTS and thus be confused with stricture or benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), while distal lesions are usually easier to detect and have a better prognosis.6 Furthermore, concomitant urethral disease such as urinary tract infection (UTI), lichen sclerosus or Human Papilloma Virus condyloma can disguise the underlying problem. In a recent series of 48 male patients with PUC, among major symptoms, Gingu et al15 reported obstruction and palpable mass in 93% of cases, followed by urethral bleeding in 66% and urethrocutaneous fistula in 26%. In the same report, the medical history was positive for UTI and multiple urethrotomies due to urethral strictures in 80% of patients. The first symptoms referred by our patient could have been related to a mild degree of obstruction due to BPH but the subsequent onset of urethral bleeding dictated further evaluations including urethroscopy, which allowed a correct diagnosis. Due to the poor quality of evidence in literature regarding treatment, the therapeutic strategy is still under debate. To improve the oncological efficacy and quality of life of patients with PUC, many efforts are being made, but prospective multi-institutional studies are needed to better define the optimal treatment strategy for this rare and devastating disease. Nowadays, available treatments are selected depending on the neoplasm location and its clinical stage, that are the 2 most important prognostic factors for male PUC.6 These features are inevitably linked to the prognosis: several case reports showed differences of up to 30% in 5-year DFS when comparing low stage and distal with high stage and proximal tumors.16,17 Radical surgery is usually performed when the tumor is documented in the bulbomembranous urethra, while in cases of distal location of the disease the approach can be less aggressive, consisting of preserving surgery together with a chemoradiotherapeutic regimen. Moreover, while surgery and radiation therapy are of benefit in lower stage disease, a high pathological stage PUC will demand multimodal treatment strategies to optimize local control and survival. These include surgery or radiotherapy with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy, with or without surgery.6–8,18–20 The role of the pathological grade appears less predictive, even if small patients series and recent literature updates indicate that high grade is a variable for a worse prognosis.3,10 In a retrospective evaluation of 2065 male patients with urethral cancer, Rabbani3 showed a negative correlation in the overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) in cases of nodal involvement, other histology versus transitional cell carcinoma and no surgery versus radical resection. Furthermore, according to the same author, radical surgery has a better outcome as compared to radiotherapy in those patients with locally advanced disease without signs of systemic spread. In accordance with prior studies, Gakis et al21 found that recurrence and OS are significantly associated with stage, grade, nodal involvement, and tumor location. Patients who desire organ preservation often have limited options for treatment. Besides, patients with proximal and invasive PUC are generally not candidates for this type of treatment.6 The therapeutic strategy adopted in the management of our patient reflected these preliminary considerations. In fact, the evidence of a high stage bulbomembranous squamous tumor with the involvement of both corpora cavernosa was an indication for a radical surgical approach already at the first diagnosis, but this option was initially refused by the patient. The treatment planned was chemotherapy based on 5-FU and Cisplatin but no local control of the disease was obtained. It is known that local recurrence is higher in male patients with bulbomembranous PUC (50–57%) compared to tumors located in the distal urethra (8–33%), because it is more difficult to achieve local control with a single treatment in cases of proximal tumors.22 The radical surgical approach previously counseled to the patient became necessary and was performed 17 months after the first diagnosis. The advanced local stage of the disease dictated an aggressive approach including cystoprostatectomy, penectomy with complete lymph node dissection, including the external and internal iliac, obturator and, because of involvement of the skin layers, superficial and deep inguinal nodes. This solution adopted in cases of invasive disease is reported in literature in 10.1% of patients according to a recent estimate but different techniques are described and there is no consensus regarding the best strategy to adopt.3 The first evidence suggesting radical resection in cases of bulbomembranous urethral cancer dates back to Marshall's case report in 1957, after which the DFS was 15 years.23 The surgical approach has since been discussed in further series in which, beyond cystoprostectomy and penectomy, resection of the inferior pubic rami was introduced in cases of locally advanced tumor of the proximal urethra.3,24 This radical technique resulted reliable in later case reports, in which a 27% difference in the 5-year OS was shown when comparing patients who underwent a radical surgical approach with those who did not.3,25 In a recent review article, the calculated local recurrence rate in patients with posterior disease who underwent exenteration, with or without lymph node dissection, decreased from 68% to 24% with the addition of en bloc pubectomy.6 Conversely, other case series have proposed a less aggressive surgical approach with bladder preservation and a continent urinary diversion. In 2005, Kobayashi et al26 described a case of T2N0M0 stage proximal urethral cancer in which urethrectomy was carried out together with prostatectomy and closure of the bladder neck, followed by a continent urinary diversion with Mitrofanoff procedure. After a follow-up of 4 years authors reported no signs of disease progression, complete continence without self-catheterization problems and a satisfactory overall quality of life. The same procedure has been adopted in other recent series for the treatment of squamous invasive carcinoma of the bulbomembranous urethra, obtaining similar results in terms of quality of life and oncological outcomes after a follow-up of 42 months.27 In the case described we could not choose a sparing approach; we performed a wide dissection including removal of the bladder beyond the urethra and penile shaft due to massive local spread of the tumor associated with nodal involvement. For the same reason we combined umbilicus-pubic and perineal incision: a scrotal fistula was clinically evident and later shown at CT scan to be neoplastic, originating in the right corpus cavernosum. In view of this situation, a better examination of the tissues involved in the disease was mandatory and we chose this kind of approach rather than a purely prepubic 1 even if it is more extensive and burdened by more complications. In a retrospective evaluation of 186 patients who underwent radical cystourethrectomy, comparing the prepubic versus perineal approach, Elshal et al12 showed a lower incidence of serious complications, and a shorter operative time and hospitalization in the first group. Among the more frequent complications in the second group the authors included wound dehiscence and infection, rectal injuries, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, even if the low number of events dictate a certain caution in interpreting their conclusions. Although our sole complication was a mild dehiscence of the perineal wound, the prepubic approach alone should be feasible in cases of proximal urethral cancer associated to bladder involvement but lacking the dramatic neoplastic spread we found.

The role of lymph node dissection in the surgical management of PUC is quite controversial. In men, the lymphatics from the anterior urethra drain into the superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes and subsequently the pelvic (external, obturator, and internal iliac) lymph nodes. Conversely, lymphatic vessels of the posterior urethra drain into the pelvic lymph nodes. In literature, few studies have focused on the role of lymphadenectomy in urethral squamous cell carcinoma; however, if the biology of this cancer mirrors that of penile squamous carcinoma, then lymph node dissection should be evaluated for minimal nodal disease.28 In this scenario, MD Anderson Cancer Center studies have reported that disease control is possible only in cases with limited lymph node involvement.10,29

Radical surgery is widely adopted in the treatment of male urethral cancer even if other approaches including chemo and radiotherapy should be taken into consideration. Advanced PUC requires a multimodal approach to maximize survival; surgery alone and radiation monotherapy have similar unfavorable results, with survival rates ranging between 0% and 38%.13 The employment of radiotherapy alone in cases of bulbomembranous cancer resulted deleterious in several case reports,30,31 while combined use with chemotherapy showed positive results.11,32 In a recent series, Cohen et al32 described a 5-year OS of 60% and a 5-year DSS of 83% in 18 patients with locally advanced disease who underwent radiotherapy, like Nigro33 for squamous cancer of the anal canal, chemotherapy with 5-FU and Mytomicin. In a retrospective study of 29 patients with invasive PUC, Kent et al8 reported similar results. So combined chemoradiation for invasive male urethral cancer offers the potential for genital preservation and is an alternative therapeutic choice in patients unfit for surgery. In 2006, Thyavihally et al11 reported their experience of 36 male patients treated surgically and with neo-adjuvant radiochemotherapy based on 5 FU and Cisplatin: after 55.1 months the 5-year OS and DFS were 49% and 23%, respectively, with markedly lower rates in patients with proximal and higher stage tumors. Recent retrospective studies have reported that patients with clinically advanced tumor stages benefited most from neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and emphasized that modern platinum-based polychemotherapeutic regimens can be effective in prolonging survival even in lymph node-positive disease. In a series of 124 patients with clinically advanced tumor stage and/or node positive disease, Gakis et al34 demonstrated an advantage of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy over surgery alone or with adjuvant chemotherapy. In our case, the patient did not undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy, considering the poor response to the first treatment with 5-FU and Cisplatin. Rather, an adjuvant chemotherapeutic regimen11 was adopted after the surgical approach due to the massive spread of the tumor.

CONCLUSIONS

Male urethral cancer of the proximal urethra is a rare, aggressive disease. Treatments available depend on the neoplasm location and its stage: radical surgery is usually adopted in cases of high pathological stage bulbomembranous urethral cancer. In lower stage and distal locations of the disease, the approach can be less aggressive, consisting of preserving surgery together with a chemoradiotherapeutic regimen. There is no consensus in literature about the most effective treatment, due also to the fact that only case series have been reported. Different retrospective experiences of extensive local therapy suggest that a wide field surgical approach may be of benefit. Patients with high stage tumors of the bulbomembranous urethra, involving the corporas, should be managed with radical surgery including the corporas up to the ischiatic tuberosity attachment, and membranous urethra in continuity with the prostate and bladder. An external urinary diversion with an ileal conduit is easier and faster than other kinds of urinary diversion. Neoadjuvant treatment could be advisable to improve a poor prognosis, even if the efficacy is not certain and, as in our case, can delay the radical treatment of the disease. There is no standard chemotherapy, but platinum-based polychemotherapeutic regimens have been successfully used in different retrospective studies.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 5-FU = 5-fluorouracyl, BPH = benign prostatic hyperplasia, CT = computed tomography, DFS = disease-free survival, DSS = disease-specific survival, LUTS = lower urinary tract symptoms, OS = overall survival, PUC = primary urethral carcinoma, TCC = transitional cell carcinoma, UTI = urinary tract infection.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swartz MA, Porter MP, Lin DW, et al. Incidence of primary urethral carcinoma in the United States. Urology 2006; 68:1164–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Visser O, Adolfsson J, Rossi S, et al. Incidence and survival of rare urogenital cancers in Europe. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48:456–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabbani F. Prognostic factors in male urethral cancer. Cancer 2011; 117:2426–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. www.seer.cancer.gov Accessed February 01, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalbagni G, Zhang Z, Lacombe L, et al. Male urethral carcinoma: analysis of treatment outcome. J Urol 1999; 53:1126–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dayyani F, Hoffman K, Eifel P, et al. Management of advanced primary urethral carcinomas. BJU Int 2014; 114:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gakis G, Witjes JA, Compérat E, et al. EAU guidelines on primary urethral carcinoma. Eur Urol 2013; 64:823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kent M, Zinman L, Girshovich L, et al. Combined chemoradiation as primary treatment for invasive male urethral cancer. J Urol 2015; 193:532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandler JI, Pool TL. Primary carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol 1966; 96:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinney CPN, Johnson DE, Swanson DA, et al. Therapy and prognosis for male anterior urethral carcinoma: an update. Urology 1994; 43:506–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thyavihally YB, Tongaonkar HB, Srivastava SK, et al. Clinical outcome of 36 male patients with primary urethral carcinoma: a single center experience. Int J Urol 2006; 13:716–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elshal AM, Barakat TS, Mosbah A, et al. Complications of radical cystourethrectomy using modified Clavien grading system: prepubic versus perineal urethrectomy. BJU Int 2011; 108:1297–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharp DS, Angermeier KW. Wein A, Kavoussi L, Novick A, et al. Surgery of penile and urethral carcinoma. Campbell-Walsh Urology Elsevier, 10th edPhiladelphia:2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed K, Dasgupta R, Vats A, et al. Urethral diverticular carcinoma: an overview of current trends in diagnosis and management. Int Urol Nephrol 2010; 42:331–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gingu C, Patrascoiu S, Surcel C, et al. Primary carcinoma of the male urethra: diagnosis and treatment. Eur Urol Suppl 2012; 11:e405. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng L, Leibovich BC, Cheville JC, et al. Squamous papilloma of the urinary tract is unrelated to condyloma acuminate. Cancer 2000; 88:1679–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eng TY, Naguib M, Galang T, et al. Retrospective study of the treatment of urethral cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2003; 26:558–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan GW, Bulkley GJ, Grayhack JT. Carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol 1967; 98:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopkins SC, Nag SK, Soloway MS. Primary carcinoma of male urethra. Urology 1984; 23:128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Licht MR, Klein EA, Bukowski R, et al. Combination radiation and chemotherapy for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the male and female urethra. J Urol 1995; 153:1918–1920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gakis G, Morgan TM, Efstathiou JA. Prognostic factors and outcomes in primary urethral cancer: results from the international collaboration on primary urethral carcinoma. World J Urol 2015; 34:97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith Y, Hadway P, Ahmed S, et al. Penile-preserving surgery for male distal urethral carcinoma. BJU Int 2007; 100:82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall VF. Radical excision of locally extensive carcinoma of the deep male urethra. J Urol 1957; 78:252–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bracken RB. Exenterative surgery for posterior urethral cancer. Urology 1982; 19:248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrer JH, Lupu AN. Carcinoma of deep male urethra. Urology 1984; 24:527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi M, Nomura M, Yamada Y, et al. Bladdersparing surgery and continent urinary diversion using the appendix (Mitrofanoff procedure) for urethral cancer. Int J Urol 2005; 12:581–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reis LO, Murillo FF, Ferreira AU. Urethral carcinoma: critical view con contemporary consecutive series. Med Oncol 2011; 28:1405–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karnes RJ, Breau RH, Lightner DJ. Surgery for urethral cancer. Urol Clin North Am 2010; 37:445–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bracken RB, Henry R, Ordonez N. Primary carcinoma of the male urethra. South Med J 1980; 73:1003–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeidman EJ, Desmond P, Thompson IM. Surgical treatment of carcinoma of the male urethra. Urol Clin North Am 1992; 19:359–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raghavaiah NV. Radiotherapy in the treatment of carcinoma of the male urethra. Cancer 1978; 41:1313–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen MS, Triaca V, Billmeyer B, et al. Coordinated chemoradiation therapy with genital preservation for the treatment of primary invasive carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol 2008; 179:536–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nigro ND, Vaitkevicus VK, Cosidine B., Jr Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum 1974; 17:354–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gakis G, Morgan TM, Daneshmand S, et al. Impact of perioperative chemotherapy on survival in patients with advanced primary urethral cancer. Results of the international collaboration on primary urethral carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2015; 26:1754–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]