Abstract

As the global burden of cardiovascular disease continues to increase worldwide, nurturing the development of early-career cardiologists interested in global health is essential in order to create a cadre of providers with the skill set to prevent and treat cardiovascular diseases in international settings. As such, interest in global health has increased among cardiology trainees and early-career cardiologists over the past decade. International clinical and research experiences abroad present an additional opportunity for growth and development beyond traditional cardiovascular training. We describe the American College of Cardiology International Cardiovascular Exchange Database, a new resource for cardiologists interested in pursuing short-term clinical exchange opportunities abroad, and report some of the benefits and challenges of global health cardiovascular training in both resource-limited and resource-abundant settings.

Keywords: cardiovascular training, delivery of health care, early career, fellowships and scholarships, mentors

Introduction

Noncommunicable diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide, of which cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality, accounting for 46.2% of noncommunicable deaths (1). Three-quarters of all CVD-related deaths occur within low- and middle-income countries (1,2). Significant resources and financial investment are required for the prevention and treatment of CVD (3,4), and many patients in low- and middle-income countries do not have access to treatment strategies considered standard of care in higher income countries (5,6). The call has been made for CVD, along with other noncommunicable diseases, to rise in priority on the global health agenda (7,8). For the past 3 years, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) has advised the United Nations on efforts to curb the incidence of noncommunicable diseases. Most recently, the ACC endorsed the global effort to reduce premature deaths from noncommunicable diseases by “25 percent by 2025” and published a statement as part of the Global Cardiovascular Disease Taskforce urging the adoption of stringent targets in this initiative (9).

In addition to advocacy, there is a need to train providers with the skill set to prevent and treat CVD in international settings (10). Over the past decade, interest in global health has increased and programs that offer international clinical and research rotations are becoming more desirable to future trainees (11), including cardiology fellows and early-career cardiologists. In 2009, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), increased their commitment and funding towards reducing the global burden of noncommunicable diseases (12) with the creation of 11 Centers of Excellence worldwide, focusing on the development of research infrastructure and training programs, and providing new research opportunities for cardiology trainees. Despite the growing interest in global CVD, there are few structured opportunities for trainees and early-career cardiologists to participate in global health initiatives. Furthermore, the impact of global health experiences on cardiovascular training among those who have participated in international clinical or research activities remains unclear., We herein briefly describe the current international educational efforts fostered by the ACC Early Career International Working Group and provide reflections from the authors’ collective international experiences regarding the challenges and importance of global health experiences in the development of early-career cardiologists.

The ACC International Cardiovascular Exchange Database

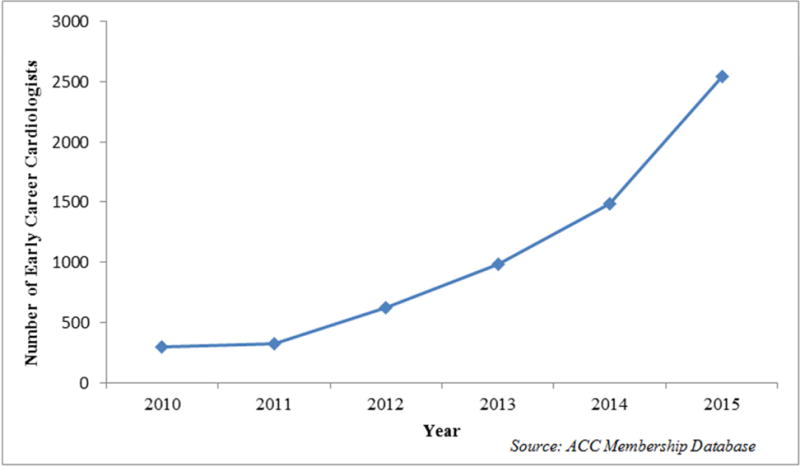

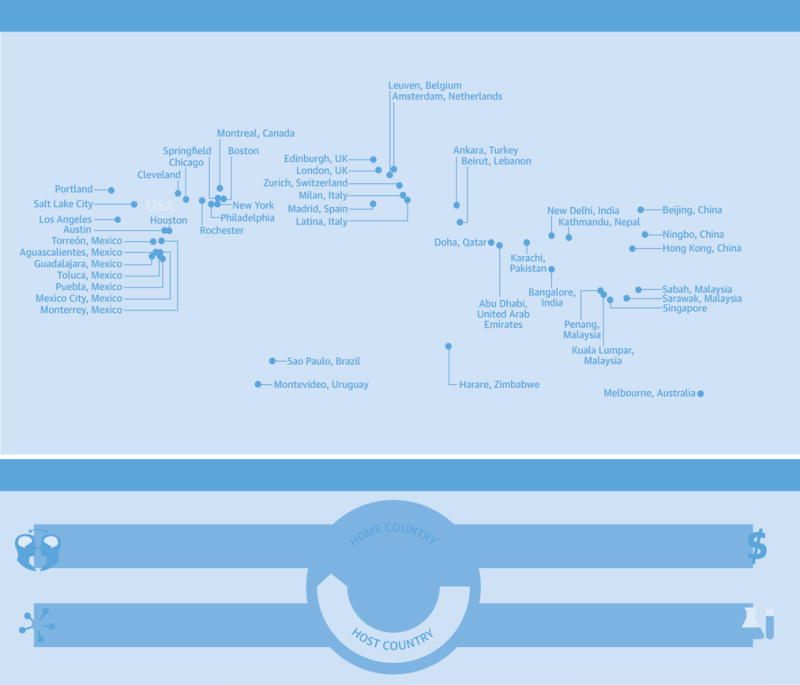

An increase in access to technology, the globalization of medical collaboration, and the speed of dissemination of care processes all create a unique and exciting opportunity for multinational educational exchange that can greatly benefit the global approach to treatment of CVD, as well as the professional growth of early-career cardiologists. One of the Early Career Section’s latest initiatives to support the growth of our colleagues and promote the exchange of cardiovascular medical skills, expertise, and knowledge has been the creation of the ACC “International Cardiovascular Exchange” database (13). This database leverages the ACC’s international network to generate a list of institutions interested in hosting visiting cardiologists. With contact information for more than 50 institutions from 24 countries (Table 1), the database aims to provide a starting point for health care professionals who would like to pursue an international cardiovascular exchange. As the number of early-career cardiologists internationally grows (Table 2 and Figure 1), significant interest in gaining experience outside one’s country has developed. Although this is a relatively new resource, and a formal feedback process is currently being developed, the database has already drawn interest and generated international exchange opportunities among participants (14). The logistics of arranging an international exchange experience, including costs and application process, vary by location. Further information on required documentation and point of contact within a selected country can be found at the International Cardiovascular Exchange website (13). Table 3 also lists additional resources available to early-career cardiologists interested in global health.

TABLE 1.

List of Participating Institutions Within the ACC International Exchange Database (13)

| Country/Region | City | Institution |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | Melbourne | The Royal Melbourne Hospital |

| Belgium | Leuven | University Hospitals Leuven |

| Brazil | Sao Paulo | Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo |

| University Hospital–University of Sao Paulo | ||

| Canada | Montreal | Jewish General Hospital |

| China | Beijing | Fu Wai Hospital |

| Ningbo | Ningbo First Hospital | |

| Hong Kong | Hong Kong | Hong Kong Academy of Medicine |

| India | Bangalore | Sri Jayadeva Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences and Research |

| New Delhi | All India Institute of Medical Sciences | |

| New Delhi | Kalra Hospital & SRCNC Pvt. Ltd. | |

| Italy | Latina | Ospedale Santa Maria Goretti |

| Milan | IRCCS Policlinico san Donato Milanese | |

| Lebanon | Beirut | American University of Beirut |

| Beirut | Makassed General Hospital | |

| Malaysia | Kuala Lampur | National Heart Institute |

| Kuala Lampur | University Malaya Medical Centre | |

| Penang | Penang Hospital Heart Centre | |

| Sarawak | Sarawak General Hospital Heart Centre | |

| Sabah | Queen Elizabeth Hospital | |

| Mexico | Aguascalientes | Cardiológica de Aguascalientes |

| Guadalajara | Social Security Mexican Institute, Western National Medical Center | |

| Mexico City | Hospital “20 de Noviembre” ISSSTE | |

| Mexico City | Instituto Nacional de Cardiología “Ignacio Chávez” | |

| Monterrey | Hospital San José Tecnológico de Monterrey | |

| Puebla | Hospital de Especialidades de la Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad IMSS | |

| Toluca | Hospital ISSEMYM de Toluca | |

| Torreón | Hospital Torreon IMSS | |

| Nepal | Kathmandu | Shahid Gangalal National Cardiac Centre |

| Netherlands | Amsterdam | Our Lady Hospital |

| Pakistan | Karachi | National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases |

| Qatar | Doha | Heart Hospital, Hamad Medical Corporation |

| Singapore | Singapore | The National Heart Centre |

| Singapore | The National University Heart Centre | |

| Spain | Madrid | University Hospital of La Paz |

| Madrid | Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda | |

| Madrid | Hospital Universitario La Paz | |

| Switzerland | University Hospital of Zürich | |

| Turkey | Ankara | Hacettepe University School of Medicine |

| United Arab Emirates | Abu Dhabi | Shaikh Khalifa Medical City |

| United Kingdom | London | The Heart Hospital |

| Edinburgh | University of Edinburgh | |

| Uruguay | Montevideo | Facultad De Medicina UDELAR |

| Zimbabwe | Harare | Parirenyatwa General Hospital |

| Institutes Within the United States Hosting Exchange Opportunities | ||

| California | Los Angeles | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center |

| Illinois | Chicago | Swedish Covenant Hospital |

| Massachusetts | Boston | Massachusetts General Hospital |

| Springfield | Baystate Medical Center | |

| Minnesota | Rochester | Mayo Clinic |

| New York | New York City | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center |

| New York City | Mount Sinai Beth Israel | |

| Ohio | Cleveland | Cleveland Clinic |

| Oregon | Portland | Oregon Health Sciences University |

| Pennsylvania | Philadelphia | Drexel University College of Medicine |

| Texas | Austin | St. David’s Medical Center-Texas Cardiac Arrhythmia Institute |

| Houston | Houston Methodist Hospital | |

| Houston | Texas Heart Institute | |

| Utah | Salt Lake City | University of Utah |

ACC = American College of Cardiology

TABLE 2.

International Early Career Cardiologists ACC Membership by Country in 2015

| Country | EC Cardiologists | Country | EC Cardiologists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 25 | Kuwait | 1 |

| Australia | 14 | Lebanon | 1 |

| Bahrain | 2 | Macedonia | 3 |

| Bangladesh | 1 | Malaysia | 75 |

| Barbados | 5 | Mexico | 220 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 16 | Myanmar | 1 |

| Brazil | 56 | Netherlands | 4 |

| Canada | 241 | New Zealand | 1 |

| Cayman Islands | 1 | Nigeria | 1 |

| Chile | 12 | Norway | 1 |

| China | 97 | Oman | 1 |

| Denmark | 1 | Pakistan | 43 |

| Dominican Republic | 9 | Panama | 1 |

| Egypt | 9 | Philippines | 1 |

| El Salvador | 1 | Russia | 15 |

| France | 3 | Saudi Arabia | 28 |

| Germany | 4 | Senegal | 1 |

| Greece | 2 | Singapore | 47 |

| Guatemala | 1 | South Korea | 25 |

| Honduras | 1 | Spain | 407 |

| Hong Kong | 5 | Sri Lanka | 2 |

| Hungary | 1 | Sweden | 3 |

| India | 231 | Switzerland | 1 |

| Iran | 1 | Taiwan | 35 |

| Iraq | 1 | Thailand | 140 |

| Ireland | 19 | Trinidad and Tobago | 4 |

| Israel | 118 | Turkey | 315 |

| Italy | 39 | Turkmenistan | 1 |

| Jamaica | 1 | Uganda | 1 |

| Japan | 12 | United Arab Emirates | 11 |

| Jordan | 4 | United Kingdom | 3 |

| Kazakhstan | 2 | Venezuela | 210 |

| Total 2,538 | |||

ACC = American College of Cardiology; EC = early-career

Figure 1.

Number of Early-Career Cardiologists Within the American College of Cardiology by Year (2010 to 2015)

TABLE 3.

Selected Resources and Research Funding Opportunities Available to Trainees and Early Career Cardiologists Interested in Global Health

| Research Funding Resources |

| 1) NIH |

| a) Fogarty International Center |

| List of Fogarty Programs for research funding (24) |

Examples of current funding opportunities available via Fogarty International Center

|

b) NHLBI:

|

2) Canadian Institutes of Health Research: provides a list of funding opportunities for global health researchers (30)

|

| 3) European Commission: provides a list of grants for European researchers including those interested in global health (32) |

| 4) List of non-NIH Funding Opportunities in global health research maintained by the Fogarty International Center (33) |

|

Additional Resources and Programs |

| 1) World Heart Federation Emerging Leaders Programme (34) |

| 2) IC-Health: Initiative for Cardiovascular Health Research in the Developing Countries (35) |

| 3) World Health Organization: provides a list of publications, programs, tools focusing on CVD worldwide (36) |

CVD = cardiovascular diseases; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Lessons Learned Abroad: Reflections from the Perspective of Early Career Cardiologists

Although the expense and time investment required for participating in international experiences can be daunting, the benefits gained by both the travelling physician and the local institution are often worth the effort. Table 4 lists the most commonly cited benefits of global health experiences for trainees. These benefits develop through personal interactions and are learned primarily through experience. Thus, they reflect similar life lessons that can be gained from exposure to a broad range of cultures and environments available internationally. In the following sections, the authors describe some of their own global health experiences, including some common challenges of global health training, provide examples of additional lessons learned that are unique to cardiovascular trainees within a global health setting, and reflect on the importance of these experiences for trainees and early-career cardiologists.

TABLE 4.

| Exposure to diseases not endemic within one’s own country |

| Exposure to patients with severe manifestations and late presentations of common diseases |

| Improvement of physical examination and procedural skills |

| Reduced dependency on laboratory testing |

| Improvement of interpersonal communication and foreign language skills |

| Development and improvement of cultural competency |

| Exposure to new technologies |

Lesson 1: Mastering the Bedside Physical Exam and Mobile Technology in Resource-Limited Settings

“Over the past several years, the use of mobile health technologies and interventions has had a positive impact on patient care and health care service delivery processes within developed nations (15). Mobile technologies can also be leveraged to address current health care system needs and delivery challenges, especially in resource-limited settings (16), a lesson I learned while working as a cardiologist and educator in Blantyre, Malawi. Practicing in areas with limited resources as a trainee was a powerful career development experience. Given the resource constraints within the hospital, such as difficulties in obtaining a basic metabolic panel or chest x-ray, careful history taking and mastery of the beside exam were essential tools for providing good patient care. Additionally, bedside availability of electrocardiograms (ECGs) and transthoracic echocardiograms were extremely limited. For example, without an echocardiogram to confirm the diagnosis, a patient with massive ascites, exophthalmos, elevated jugular venous pressure, and no lower extremity edema often had either endomyocardial fibrosis or Burkitt’s lymphoma. Now, with the introduction of smartphones capable of providing an instant ECG rhythm strip and a pocket-sized echocardiogram, patients can get more rapid cardiovascular diagnoses. For trainees, using this technology has improved their physical exam and hands-on skills. Although it is an unusual dichotomy that a more advanced technology has become an essential extension of the history and physical exam in a resource-limited setting, it helps trainees develop more detailed assessments and plans, while simultaneously increasing the availability of an otherwise limited resource for patients.”

Lesson 2: Learning New Skills and Using Technologies Not Yet Available in the United States

“European markets often have experience in devices and interventions years earlier than the United States, mostly due to the differences in approval processes between the Conformité Européenne mark and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (17). This leads to delayed or limited access to new treatment choices in the United States, and a preference by medical device companies for European markets for initial release, which has specific implications for U.S. physicians, as well as patients.

For an early-career cardiologist in the United States interested in an emerging field, such as interventional structural heart disease, it is often difficult to obtain enough clinical volume during the early phase. This is due to a combination of late access to technology, early restriction of devices to only within the context of clinical trials, and, in many cases, preferential case assignment to established and more senior physicians at a center. Having had further training and now being on the staff of the Cardiovascular Center in Frankfurt, Germany after completing a U.S.-based interventional cardiology fellowship program has provided exposure to a much larger clinical volume and to new technologies at an earlier career stage. Exposure to new technologies at an earlier career stage and to operators with more experience enhances one’s clinical competence. In addition, connections made with key opinion leaders abroad allow a closer relationship and partnership, which fosters clinical research, innovation, and intercontinental scientific collaborations. This can help disseminate new techniques and findings to the U.S. community, as well as provide common ground to test and validate these interventions in the future.”

Lesson 3: Combining Work Efficiency and “Big Data”

“As a trainee, one of the biggest challenges is learning how to work quickly and efficiently in a busy clinical practice. This is a challenge across many academic health care systems, but one that was actively addressed at The Fu Wai Hospital in Beijing, China. The hospital has 12 catheterization laboratories that run 2 shifts totaling 18 h per day. The efficiency with which complex cases were performed and patients were treated was extraordinary, and can be a significant case study for those interested in running a more lean and streamlined cardiovascular division. Additionally, there are over 100 fellows and research statisticians working side by side with clinicians and every patient is placed into a large data registry. Despite their high clinical volume, internal quality review programs were essential in maintaining and delivering high-quality care. Having this experience allowed me to witness, in real-time, how ‘big data’ can be used for individual patient care, research, and improvement of workflow processes. Whereas,, in places like the United States, the potential for ‘big data’ to revolutionize cardiovascular care is still in its infancy, in some countries it is already a reality.”

Lesson 4: Using Evidence-Based Medicine When No “Evidence” Exists

“Understanding how to manage and treat hypertension in resource-limited settings, such as Khartoum, Sudan, is complex. First, the majority of physician visits are for urgent care and not for the management of noncommunicable diseases. Secondly, whereas U.S.-based hypertension treatment guidelines suggest that first-line antihypertensive treatment for a black population should include diuretic agents or calcium-channel blockers (18), these medications may not always be available in the pharmacy. For those who are prescribed diuretic agents, medication choice is also influenced by whether patients will return for a laboratory visit to check a basic metabolic profile. Although these challenges are certainly not unique to Sudan and are also challenges in the United States, having this experience while a trainee underscores the various social determinants of health that one must continuously consider when treating patients both here and abroad.

Recognizing the unique challenges to diagnosis and treatment of CVD within low- and middle-income countries, such as Sudan, is crucial in developing cost-effective and culturally relevant treatment plans, when addressing the growing burden of noncommunicable diseases in countries within sub-Saharan Africa. Additionally, given the growing evidence that CVD varies with ethnic origin (19), this training experience in Sudan also helped highlight the challenges in adopting U.S.-based cardiovascular treatment guidelines that have not been validated in the particular population where one is practicing, and underscores the need for further epidemiological research in global health settings.”

Lesson 5: Forming New Global Cardiovascular Disease Research Collaborations

“Lessons learned while spending time working as an NIH Fogarty International Clinical Research Fellow in Buenos Aires, Argentina at the Institute of Clinical Effectiveness and Health policy as part of the Southern Cone American Center of Excellence of Cardiovascular Health team on the study entitled “Southern Cone Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Factors Detection and Follow up” include developing multidisciplinary grant applications, analyzing epidemiological data, and learning how to navigate many different hospital systems at multiple international sites with varying degrees of research resources. The main lesson learned was that to successfully implement research in this setting, it was impactful to focus on local research priorities and common large-scale issues, such as hypertension or smoking cessation. Furthermore, successful partnerships, such as that between the Institute of Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy in Argentina and Tulane University in the United States, can lead to collaborative problem solving and development for both groups. Forming these global cardiovascular research and mentorship relationships as a trainee provides one with a broader network of collaborators at a critical time in the transition to an academic early-career cardiologist.”

Lesson 6: “Choosing Wisely:” Learning Cost-Effectiveness

“The dichotomy of medical care in low- and middle-income countries was evident during time spent at an academic hospital in Mumbai, India. Those with financial means have access to advanced contemporary cardiovascular services, such as percutaneous left ventricular assist devices and transcatheter aortic valve replacements. Unfortunately, poorer patients are often managed medically until their families can accumulate monetary funds to purchase more costly treatments, and medical wards are often overcrowded with patients. The cardiac catheterization laboratory highlights the lack of resources available to treat the burgeoning hospital census: all disposables, including the drapes, shield covers, syringes, and needles, are resterilized and reused to contain costs. The choice of pharmacological therapy, devices, and products depend on the resources available to the patient’s family. It was rather a revelation of what is taken for granted in the health care system in the United States. Thus, careful triage, was paramount, and one learned early on how to choose from limited resources. In the current U.S. health care environment and for the future, it is crucial for the practitioner to learn how to best utilize the available health care resources to provide the highest quality of care for patients. These experiences teach one the concept of ‘choosing wisely’ and enables one to better teach students, residents, and fellows the fundamental health care concepts of triage and resource allocation.”

International Exposure Shapes and Refines the Cardiology Trainee

As these aforementioned experiences highlight, there are many benefits of global health experiences for cardiology trainees, from both a clinical and a research perspective. Because global health clinical training opportunities often challenge trainees to deliver health care in resource-limited settings, trainees who spend time abroad develop cost-effective skills that can be applied within their own domestic communities. These are essential practices to acquire as early-career cardiologists during the current economic environment and the era of health care reform (20). Additionally, techniques learnt in resource-limited environments can have an impact on care provided in higher-income countries: as an example, care provided in large natural disasters usually requires experience in improvised medical treatments and therapeutics, as well as in triaging of critically-wounded patients. Besides learning cost-effectiveness, trainees spending time in low- and middle-income countries may be exposed to the use of low-cost diagnostic mobile imaging devices used for point-of-care testing, which can also be adapted and used in underserved areas within their own countries. Lastly, for trainees spending time abroad in higher-income countries, the exposure to new technologies at an earlier career stage and to operators with more experience enhances one’s clinical competence.

In addition to clinical training, the experience of working abroad can also influence a trainee’s decision to pursue a research career focusing on global health and cardiology. For those interested in global CVD research, there are several funding pathways via the NIH, as well as nonprofit organizations and foundations (Table 3) (21). These intercontinental research collaborations improve local research capacity for both low- and middle-income countries and domestic-based U.S. researchers. Additionally, as more multinational cardiovascular data registries are created and an increasing number of prospective cohort and randomized clinical trials are being conducted via international collaborations, more opportunities for translational cardiovascular research via multidisciplinary collaborations will be available.

A new emerging field within global health is implementation science or “global health delivery.” Although current evidence-based interventions exist for noncommunicable diseases, one of the unique challenges in low- and middle-income countries is implementing these interventions in resource-constrained settings (22). Furthermore, many of these evidence-based interventions have been validated mostly in American and European populations, and not necessarily in the population where one is practicing. Additionally, there is often a health care delivery “gap” due to a lack of human resources, medications, and/or availability of adequate health care facilities and programs for noncommunicable disease management. Because implementation research can generate knowledge applicable to a variety of resource-limited settings in low- and middle-income countries, and even within high-income countries (22), early-career cardiologists with these global health research experiences will provide a complementary perspective and an additional skill set to the academic research environment, both domestically and internationally. Furthermore, these trainees may be uniquely equipped to influence future policies and research priorities.

Additional Challenges Faced by the Global Health Trainee

In addition to the time investment and financial costs associated with international clinical and/or research experiences, there can be some unexpected challenges and untoward consequences secondary to the local geopolitical environment that can negatively impact training. As a consequence of the increased interest in global health, there has been a rise in the importance of global health issues across the international political landscape (23). Global health issues are now often linked with foreign policies (23) and influenced by a country’s local geopolitical environment. For example, in countries with minimal health care capacity and infrastructure, a local outbreak of an infectious disease can rapidly shift health care priorities away from noncommunicable diseases, such as CVD. Priorities across major funding institutions within high-income countries can likewise shift, depending on the far-reaching consequences of an emerging infectious disease threat on the global economy. Political instability within a country can also hinder clinical experiences, and disrupt longitudinal research projects and multinational collaborations. This can be detrimental, especially for those supported by early-career development awards. Furthermore, political turmoil often leads to increased migration within countries and immigration to higher-income countries, such as the United States, and may ultimately affect population demographics and common disease pathologies domestically. As a result, early-career global health cardiologists must be mindful of the local geopolitical environment within countries abroad and the impact it may have on one’s training, both domestically and internationally. Learning how to successfully navigate the local geopolitical environment will be an essential part of global health training.

Lastly, for those interested in a global health cardiovascular research career and/or long-term clinical experiences abroad, additional challenges may also arise with regard to career planning, mentorship, and dedicated institutional support during extended time away (21).

Conclusion

International clinical exposure is a key component in the development of many early-career cardiologists. Immersion in a foreign culture with new sets of challenges, whether in a resource-limited or resource-abundant environment, tends to forge the best traits in practitioners: courage, persistence, creativity, and innovation. Global health experiences have the potential to create truly impactful clinical situations, combined with an appreciation for practice in an environment where resources may not always be readily available. These experiences create a deep desire for improved collaboration worldwide and create clinicians who value every resource made available in whichever country they ultimately practice. Finally, the potential for research, early use of novel technologies, and new discovery remains a key driver for those seeking such experiences. Early-career cardiologists, in particular, are urged to spend time outside their comfort zones, in global health rotations or experiences, in an effort to grow their individual health care perspectives, create new collaborative relationships, and further their careers. Ultimately, the prevention and treatment of the growing burden of CVD worldwide will require a cadre of cardiologists with global health skills and expertise.

Central Illustration. Global Health Training for New Cardiologists: International Opportunities.

(A) Countries with sites participating in the ACC International Cardiovascular Exchange Program available to host visiting cardiologists. (B) Areas of international collaboration and global health cardiology training opportunities for cardiovascular trainees participating in exchange programs.

ACC = American College of Cardiology

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristin West, Amalea Hijar, and Stefan Lefebvre from the American College of Cardiology for their assistance in the preparation of the paper.

Funding: Dr. Abdalla is supported by HL117323-02S2 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Vedanthan is supported by K01 TW 0099218-04 from the NIH. Dr. El Chami is supported by a research grant from Medtronic. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or of Medtronic.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACC

American College of Cardiology

- CVD

cardiovascular disease(s)

- EC

early-career

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- NHLBI

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors have reported that they have no relationships related to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable disease 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2014. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/148114/1/9789241564854_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed November 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moran AE, Tzong KY, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Variations in ischemic heart disease burden by age, country, and income: the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors 2010 study. Glob Heart. 2014;9:91–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendriks ME, Bolarinwa OA, Nelissen HE, et al. Costs of cardiovascular disease prevention care and scenarios for cost saving: a micro-costing study from rural Nigeria. J Hypertens. 2015;33:376–684. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim SS, Gaziano TA, Gakidou E, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular disease in high-risk individuals in low-income and middle-income countries: health effects and costs. Lancet. 2007;370:2054–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giday A, Weldeyes E, O’Mara J. Characteristics and management of patients with acute coronary syndrome at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababab, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2013;51:269–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moustaghfir A, Haddak M, Mechmeche R. Management of acute coronary syndromes in Maghreb countries: The ACCESS (ACute Coronary Events - a multinational Survey of current management Strategies) registry. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;105:566–77. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. Lancet NCD Action Group; NCD Alliance. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011;377:1438–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuster V, Voute J, Hunn M, et al. Low priority of cardiovascular and chronic diseases on the global health agenda: a cause for concern. Circulation. 2007;116:1966–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.733444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith SC, Jr, Chen D, Collins A, et al. Moving from political declaration to action on reducing the global burden of cardiovascular diseases: a statement from the Global Cardiovascular Disease Taskforce. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2151–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truglio J, Graziano M, Vedanthan R, et al. Global health and primary care: increasing burden of chronic diseases and need for integrated training. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012;79:464–74. doi: 10.1002/msj.21327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, et al. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med. 2009;84:320–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181970a37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nabel EG, Stevens S, Smith R. Combating chronic disease in developing countries. Lancet. 2009;373:2004–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ACC International Cardiovascular Exchange Database. American College of Cardiology. Available at: www.acc.org/internationalexchange. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 14.Kalra A. Organizing an international elective: a unique opportunity for cardiovascular fellows. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2429–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.10.014. discussion 2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, et al. The effectivenss of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Medicine. 2012:10.e1001362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakrabarti R, Perera C. The growth of mHealth in low resource settings. J Mob Technol Med. 2013;2:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodall S, Tom J. Regulation and access to innovative medical technologies: a comparison of the FDA and EU approval processes and their impact on patients and industry. Boston Consulting Group; Jun, 2012. Available at: http://www.eucomed.org/uploads/ModuleXtender/Newsroom/97/2012_bcg_report_regulation_and_access_to_innovative_medical_technologies.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311:507–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhillon RS, Clair K, Fraden M, et al. Hypertension in populations of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2014(384):234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61211-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panosian C, Coates TJ. The new medical “missionaries”–grooming the next generation of global health workers. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1771–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bloomfield GS, Huffman MD. Global chronic disease research training for fellows: perspectives, challenges, and opportunities. Circulation. 2010;121:1365–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.923144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vedanthan R. Global health delivery and implementation research: a new frontier for global health. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78:303–5. doi: 10.1002/msj.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feldbaum H, Lee K, Michaud J. Global health and foreign policy. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32:82–92. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fogarty Programs. NIH Fogarty International Center. Available at: http://www.fic.nih.gov/Programs/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 25.Fogarty Emerging Global Leader Award. NIH Fogarty International Center. 2015 Available at: http://www.fic.nih.gov/Programs/Pages/emerging-global-leader.aspx. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 26.Global Health Program for Fellows and Scholars. NIH Fogarty International Center. 2015 Available at: http://www.fic.nih.gov/Programs/Pages/scholars-fellows-global-health.aspx. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 27.Fulbright-Fogarty Fellows and Scholars in Public Health. NIH Fogarty International Center. 2015 Available at: http://www.fic.nih.gov/Programs/Pages/fulbright-fellowships.aspx. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 28.United Health and NHLBI Collaborating Centers of Excellence. NIH National Heart. Lung and Blood Institute; 2015. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/org/globalhealth/centers/index.htm. Accessed November 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases. NIH National Heart. Lung and Blood Institute; 2013. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/org/globalhealth/alliance-chronic-diseases/index.htm. Accessed November 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.International and global health: Funding. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. 2013 Available at: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/27173.html. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 31.Transatlantic Networks of Excellence. Fondation Leducq. Available at: https://www.fondationleducq.org/transatlantic-networks-of-excellence/overview/. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 32.Kollar SJ, Ailinger RL. International clinical experiences: long-term impact on students. Nurse Educ. 2002;27:28–31. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200201000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller WC, Corey GR, Lallinger GJ, et al. International health and internal medicine residency training: the Duke University experience. Am J Med. 1995;99:291–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Funding Opportunities. European Commission. Available at : http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/portal/desktop/en/opportunities/index.html. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 35.Non-NIH Funding Opportunities – Grants and Fellowships. NIH Fogarty International Center. Available at: http://www.fic.nih.gov/Funding/NonNIH/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 36.Emerging Leaders Programme. World Heart Federation. 2015 Available at: http://www.world-heart-federation.org/what-we-do/the-emerging-leaders-programme/. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 37.Initiative for Cardiovascular Health Research in the Developing Countries. IC-Health. Available at: http://www.ichealth.org. Accessed November 24, 2015.

- 38.Cardiovascular Diseases. World Health Organization; 2015. Available at: http://www.who.int/topics/cardiovascular_diseases/en/. Accessed November 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]