Abstract

Background

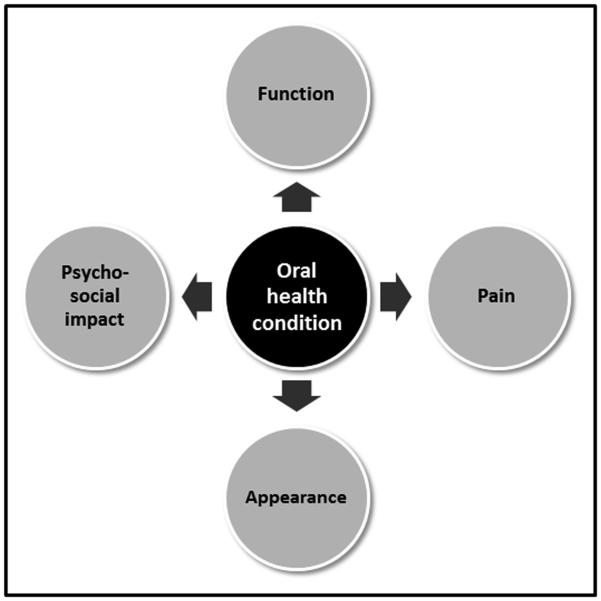

How dental patients are affected by oral conditions can be described with the concept of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). This concept intends to make the patient experience measurable. OHRQoL is multidimensional and Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact were suggested as its four dimensions and consequently four scores are needed for comprehensive OHRQoL assessment. When only the presence of dimensional impact is measured, a pattern of affected OHRQoL dimensions would describe in a simple way how oral conditions’ influence the individual.

Objective

By determining which patterns of impact on OHRQoL dimensions (Oral Function-Orofacial Pain-Orofacial Appearance-Psychosocial Impact) exist in prosthodontic patients and general population subjects, we aimed to identify in which combinations oral conditions’ functional, painful, aesthetical, and psychosocial impact occurs.

Methods

Data came from the Dimensions of OHRQoL Project with OHIP-49 data from 6,349 general population subjects and 2,999 prosthodontic patients in the Learning Sample (N=5,173) and the Validation Sample (N=5,022). We hypothesized that all 16 patterns of OHRQoL dimensions should occur in these individuals who suffered mainly from tooth loss, its causes and consequences. A dimension was considered impaired when at least one item in the dimension was affected frequently.

Results

The 16 possible patterns of impaired OHRQoL dimensions were found in patients and general population subjects in both Learning and Validation Samples.

Conclusions

In a four-dimensional OHRQoL model consisting of Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact, oral conditions’ impact can occur in any combination of the OHRQoL dimensions.

Keywords: oral health-related quality of life, dimensions, prosthodontic patients, general population

Introduction

Patients seek care from oral health professionals to address their current oral health problems or, even better, in order to prevent future problems. How the patient perceives the oral health situation can be characterized with the concept of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). It intends to capture how oral conditions impact patients’ everyday life. It makes this complex impact measurable, i.e., by providing a score by using OHRQoL questionnaires. The concept is multidimensional (1), i.e., several attributes within the construct OHRQoL, so called dimensions, exist. In international prosthodontic patients and general population subjects, Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact were identified as a parsimonious and clinically intuitive set of OHRQoL dimensions (2, 3). While conceptually each OHRQoL dimension has a score that characterizes the severity of the impairment; in the simplest way oral conditions’ influence on the individual can be characterized by which individual or combination of the four dimensions are affected or not. A set or pattern of affected OHRQoL dimensions would result. Such an approach is clinically meaningful because it would characterize a particular patient as suffering mainly from functional, painful, aesthetical, or broader problems, or a combination of problems. Treatment strategies could consequently be tailored to these problem areas. Our theory of oral health would also advance by using OHRQoL dimensions. These dimensions represent core areas where pathogenetically very different oral diseases influence individuals in similar ways, and general principles can be derived from what patients report to experience as soon as a disease affects them.

Because these OHRQoL dimensions occur as sets, a first step would be to characterize which patterns of impaired dimensions exist for a certain condition in a target population. Caries and periodontitis are dentistry’s most common conditions, with tooth loss as their final stage of disease progression. Tooth loss can be seen as dentistry’s typical physical outcome (4), but tooth loss itself can influence oral structures in various ways and can result in even further outcomes. Tooth loss is often treated by fixed or removable prosthodontic appliances, which become an integral part of a patient’s physical oral health situation. Therefore, tooth loss, together with the oral diseases leading to it and the structural sequelae following it, represents the principal factor influencing the oral health condition of many individuals (5). How dentistry’s most comprehensive concept to measure perceived oral health (OHRQoL) would be affected by this broader concept of tooth loss, its related diseases, and structural consequences, is of theoretical and practical interest. To approach this question first on the OHRQoL dimensional level is parsimonious but informative to detect general principles relevant to which dimensions are individually, or in combination, affected. Typical dental patients and also general population subjects, the population where dental patients conceptually arise from and return after successful treatment, would be appropriate target populations for the research question. The Dimensions of OHRQoL Project (4) contains such patients and general population subjects and would be suitable to investigate the occurrence of OHRQoL patterns in a large and diverse sample of subjects.

It was the aim of this study to determine which patterns of impact on OHRQoL dimensions of Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact exist in international prosthodontic patients and general population subjects.

Material and methods

Subjects and data

Data came from the Dimensions of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (DOQ) Project (4). The project contained 49-item OHIP (6) data from prosthodontic patients and general population subjects from Croatia, Germany, Hungary, Japan, Slovenia, and Sweden - countries with validated OHIP instruments (7-12). The current study used the Learning Sample of the DOQ Project, containing 5,173 subjects (3,177 general population subjects and 1,996 prosthodontics patients), to explore which dimensional patterns existed, and the Validation Sample, containing 5,022 subjects (3,172 general population subjects and 1,850 prosthodontic patients), to validate the findings about presence of patterns. More details about OHIP and the levels of impaired OHRQoL were provided in the overview about the DOQ Project (4).

Data analysis

Four OHRQoL dimensions were identified in previous exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (Table 1): Oral Function (10 items), Orofacial Pain (7 items), Orofacial Appearance (6 items), and Psychosocial Impact (18 items) (2, 3).These dimensions can appear in 16 combinations (Table 2): 1 set of dimensions without impact (none of the dimensions is notably affected), 4 sets of only one dimension impacted, 6 sets of two dimensions impacted, 4 sets of three dimensions impacted, and 1 set with all four dimensions impacted. We were most interested in a substantial dimensional impact. Therefore, because OHRQoL impacts are measured with OHIP items in a frequency metric, we considered only frequent items’ responses. We counted a dimension as being affected when at least one OHIP item of this dimension had occurred ‘fairly often’ or ‘very often’. For each of the 16 combinations of dimension impact, we computed the percentage of occurrence separately for prosthodontic patients and general population subjects in both the Learning Sample and the Validation Sample.

Table 1.

Forty-one items of the Oral Health Impact Profile assigned to the OHRQOL dimensions Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact

| Oral Function | Orofacial Appearance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Item no.* | Content | Item no.* | Content |

| 1. | Difficulty chewing | 3. | Noticed tooth which doesn't look right |

| 2. | Trouble pronouncing words | 4. | Appearance affected |

| 6. | Taste worse | 19. | Worried |

| 16. | Uncomfortable to eat | 20. | Self-conscious |

| 24. | Speech unclear | 22. | Uncomfortable about appearance |

| 25. | Others misunderstood | 31. | Avoid smiling |

| 26. | Less flavor in food | ||

|

|

|||

| 28. | Avoid eating | Psychosocial Impact | |

|

|

|||

| 29. | Diet unsatisfactory | 23. | Tense |

| 32. | Interrupt meals | 33. | Sleep interrupted |

| 34. | Upset | ||

|

|

|||

| Orofacial Pain | 35. | Difficult to relax | |

|

|

|||

| 10. | Painful aching | 36. | Depressed |

| 11. | Sore jaw | 37. | Concentration affected |

| 12. | Headaches | 38. | Been embarrassed |

| 13. | Sensitive teeth | 39. | Avoid going out |

| 14. | Toothache | 40. | Less tolerant of others |

| 15. | Painful gums | 41. | Trouble getting on with others |

| 17. | Sore spots | 42. | Irritable with others |

| 43. | Difficulty doing jobs | ||

| 44. | Health worsened | ||

| 45. | Financial loss | ||

| 46. | Unable to enjoy people's company | ||

| 47. | Life unsatisfying | ||

| 48. | Unable to function | ||

| 49. | Unable to work | ||

Item number in original 49-item OHIP (6)

Table 2.

Frequency of patterns of affected OHRQoL dimensions in patients and general population subjects from the Dimensions of OHRQoL Project

| OHRQoL dimension pattern | Learning Sample | Validation Sample | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Pattern # | Number of affected dimensions |

Oral

Function |

Orofacial

Pain |

Orofacial

Appearance |

Psychosocial

Impact |

Patients | General population |

Patients | General population |

|

| |||||||||

| Impact present or absent [X/-] | Proportion of subjects with pattern [%] | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| 1 | 0 | - | - | - | - | 46.9 | 73.2 | 52.3 | 73.0 |

|

| |||||||||

| 2 | 1 | X | - | - | - | 5.2 | 1.6 | 4.5 | 2.2 |

| 3 | 1 | - | X | - | - | 7.4 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 5.8 |

| 4 | 1 | - | - | X | - | 4.1 | 4.5 | 2.9 | 3.8 |

| 5 | 1 | - | - | - | X | 3.8 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 2.9 |

|

| |||||||||

| 6 | 2 | X | X | - | - | 4.4 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 0.8 |

| 7 | 2 | X | - | X | - | 1.9 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 0.7 |

| 8 | 2 | X | - | - | X | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| 9 | 2 | - | X | X | - | 2.5 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2.0 |

| 10 | 2 | - | X | - | X | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| 11 | 2 | - | - | X | X | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

|

| |||||||||

| 12 | 3 | X | X | X | - | 3.6 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 1.0 |

| 13 | 3 | X | X | - | X | 3.9 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 1.5 |

| 14 | 3 | X | - | X | X | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| 15 | 3 | - | X | X | X | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

|

| |||||||||

| 16 | 4 | X | X | X | X | 10.1 | 2.5 | 9.6 | 3.0 |

Research hypothesis

We hypothesized that all combinations of frequent dimensional impact are present in prosthodontic patients as well as general population subjects.

We based our hypothesis on the various functional, painful, aesthetical, and psychosocial influences of tooth loss, and the diseases and processes leading to it and sequelae arising from it. We anticipated individually-affected dimensions, combinations of two or three dimensions affected, but also the co-occurrence of all (four) dimensions affected. We expected that all 16 combinations can occur because the mechanisms that lead to an individually-affected dimension can coexist. Finally, the oral conditions’ direct (primary) dimensional impact can lead to an indirect (secondary) dimensional impact. This situation would also give rise to a pattern of multiple dimensions being compromised. All patterns should occur in both populations because the broader concept of tooth loss affects individuals in general, and not just patients.

Results

Patterns of impacted dimensions in the Learning Sample

In prosthodontic patients, we found all 16 combinations of the four dimensions (Table 2). About half of the patients did not present with a frequent dimensional impact. When frequent impacts were found, most often only one dimension was affected compared to sets of two, three, or four dimensions. As individual effects, functional and painful impacts occurred most often. The combination that occurred most often (among frequent impacts) was four affected dimensions.

In general population subjects, we also found all 16 combinations (Table 2). The majority of subjects (about three-quarters) did not present with a frequent dimensional impact. Findings for affected dimensions were different in general population subjects compared to the patients described previously. In the general population, the painful and aesthetical dimensional patterns were affected most, and the most prevalent pattern was an isolated effect on the dimension of Orofacial Pain.

Patterns of impacted dimensions in the Validation Sample

Findings in this sample were very similar to those in the Learning Sample for prosthodontic patients as well as for general population subjects. Overall, patients had slightly fewer problems but the prevalence for patterns did not change substantially, confirming the results in the Learning Sample.

Model of pathways among OHRQoL dimensions

Based on the observed patterns of frequent dimensional impact, a graphical presentation (Figure 1) can be derived, presenting pathways from oral disease/conditions to major areas of patient-perceived impact (Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact as dimensions OHRQoL.) The four dimensions can be impacted individually as well as in 11 unique combinations.

Figure:1.

Oral health conditions’ influence on OHRQoL dimensions Oral Function, Oro-facial Pain, Oro-facial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact.

Discussion

Oral diseases’ impact can occur in four major areas: Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact. These areas are called the dimensions of OHRQoL. All clinically plausible combinations of the four dimensions can be observed in typical dental patients and in general population subjects.

Dimensional influence of oral conditions, in particular tooth loss

Dimensions of OHRQoL have been investigated with different methods. For example, studies used structural equation models (13), exploratory factor analysis (14), confirmatory factor analysis (15), or experts’ assignment of items to dimensions (16). Previous studies have also considered a variety of subject populations such as Turkish patients with Behcet's disease and recurrent aphthous stomatitis (14) or non-patient populations such as Spanish healthy workers (15). Using the population of prosthodontic patients, who we considered typical dental patients (4), we discuss how physical oral health – mainly determined by tooth loss, its causes and consequences - can influence OHRQoL dimensions. The examples and principles derived from the patients apply in a very similar fashion to general population subjects.

A single affected dimension – a focused influence

Patients (and general population subjects) can have, in its simplest form, an impact in one of the four OHRQoL dimensions. This finding is consistent with a 4-dimensional OHRQoL model and it strengthens its conceptual basis – that each dimension is important in its own right and represents an essential component of perceived oral health. For the dimensions Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, and Orofacial Appearance, this finding is intuitive. There are many conceivable clinical situations that can lead to a focused influence. In fact, certain dimensional impact can be attributed to certain oral structures. For example, posterior tooth loss can have a substantial functional impact (17, 18), e.g., though impaired chewing (19, 20), and anterior tooth loss can have a notable aesthetical impact (21). The various oral, dental, and orofacial pain conditions certainly represent another source of impact, e.g., temporomandibular disorder pain (22, 23). These pain conditions can accompany structural changes, but don’t necessarily have to, i.e., pain can occur without substantial structural deterioration of a hard and/soft oral tissue(s), leading to an isolated effect on Orofacial Pain. It is noteworthy that Psychosocial Impact can occur as a single dimension. Although a majority of psychosocial influence can be expected to be the consequence of a functional, painful, or aesthetical problem (see discussion of two affected dimensions in the next paragraph), e.g., certain situations can lead to a substantial Psychosocial Impact independently of other factors. For example, posterior tooth loss may not cause a substantial functional, painful, or aesthetical impact; however, patients may be mindfully worried or experience concerns about the situation. Also, low-grade functional, painful, or aesthetical problems may not be enough to cause a substantial dimensional impact, but the cumulative Psychosocial Impact related to several dimensions may result in Psychosocial Impact as the most affected dimension.

Multiple dimensions affected – complex influence with direct and indirect effects

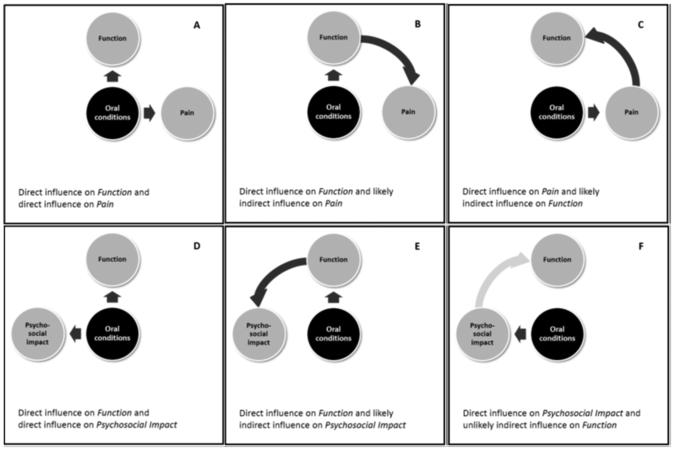

We observed combinations of affected dimensions. Unfortunately, our cross-sectional study design was not able to use time to differentiate between two important scenarios for two affected dimensions (three dimensions just represent an extension of the discussed principles): (i) the two dimensions are simultaneously affected by the oral condition, or (ii) one dimension is primarily affected and the other dimension is affected as a consequence. For example, anterior and posterior tooth loss can co-exist, leading to two simultaneously affected dimensions (Figure 2, Panel A). Conversely, functional limitations due to an impaired occlusion are sometimes treated with occlusal adjustment and prosthodontic appliances, leading to (long-term) functional improvement but occasionally also to (acute) pain and discomfort related to the adaption to the new situation. A direct functional impact in the stomatognathic system, e.g., hyper-, hypo- or dysfunction caused by an oral or systemic condition, can lead to an indirect effect on pain and discomfort (Figure 2, Panel B.). Certainly, pain as an oral condition’s primary impact (again a direct effect) can lead to functional problems, e.g., tooth pain can result in chewing restrictions (Figure 2, Panel C). The functional influence would be an indirect affect. Clinical experience is even more informative for scenarios involving the Psychosocial Impact dimension. Again, a simultaneous (direct) impact can occur with other dimensions (Figure 2, Panel D). Direct effects of the oral condition on the dimensions of Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, and Orofacial Appearance can be followed by an indirect Psychosocial Impact (Figure 2, Panel E). Less likely and less frequent seems the opposite scenario (Figure 2, Panel F). While clinical experience is informative about the direction of effects and the frequency of certain scenarios, even more information can be expected from treatment studies. When tooth loss is “reversed” by fixed and removable prosthodontics, dimensional impacts are expected to change. For the majority of patients, impact should subside after completed treatment and OHRQoL should improve. But in some cases, new impact may appear as a side effect from treatment (24). In other cases, treatment may not be able to address the patient’s condition substantially. In fact, in a consecutive series of prosthodontic patients from two treatment centers, almost every fifth patient reported that the oral health situation after treatment was the same or worse despite the fact that more than half of the patients felt a lot better after therapy (25).

Figure:2.

Direct and indirect influence of oral conditions when two or more OHRQoL dimensions are affected demonstrated for two scenarios (Panel A–C: Oral Function and Oro-facial Pain, Panel D–F Oral Function and Psychosocial Impact).

The previously explained mechanisms of how dimensional impact can occur translate easily to the situation when four dimensions are affected. Impact from lost posterior teeth (mainly function), lost anterior teeth (mainly appearance), the presence of a dental/oral/orofacial pain, and a general worry/concern about the oral health situation can lead to direct effects on all four dimensions. More likely are a combination of direct and indirect effects, e.g., that functional, painful, and aesthetical problems also have a secondary psychosocial influence.

Comparison with the literature

The approach of using OHRQoL questionnaire items to inform about dimensional patterns is not new. OHIP-14 responses in general UK and Australian population subjects targeted the 7 original OHIP domains in a smaller set of four major dimensions (Functional Limitation, Pain and Discomfort, Disability, and Handicap). Of the 16 possible combinations, 13 combinations existed in the data based on the authors’ criteria. While instruments (OHIP-14 versus OHIP-49) and dimensions measured were different in the study of Nuttall et al. and our study, some findings were similar. Both studies agreed on the number (four) of basic components within the concept OHRQoL and, therefore, had 16 available combinations of OHRQoL dimensions.

Nuttall’s study found most patterns occurred, whereas we observed all. However, despite the similarity, two major differences between the models exist. First, our dimension Orofacial Appearance does not have a direct counterpart in the other study. Second, the Nutall study’s dimensions were related in a hierarchical system (Functional Limitation as well as Pain and Discomfort represent one level, Disability a second, and Handicap a third). The last two levels (Disability and Handicap) would represent in our opinion, just different degrees of a broader, psychosocial influence rather than two separate categories. Support for this opinion comes from a previous study where psychological impact and social impact were identified by experts as a more parsimonious grouping of OHIP items rather than the original domains psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap (16). Our OHRQoL model is not hierarchical due to conceptual reasons and because the cross-sectional nature of our data does not support inference about time effects. However, the concept of a hierarchy from less to more severely impaired oral health is incorporated in the continuous nature of our four dimensions. Each of our four dimensions represents a spectrum, or continuum, from the perception of less to more affected oral health. This hierarchical and spectrum character of (oral) health-related quality of life models (26, 27) is well documented.

Methodological considerations

We measured dimensional impact derived from problems occurring “fairly often” or “very often.” These responses represent a frequent, i.e., considerable, impact; therefore, dimensional impacts are substantial for the individual. OHIP questionnaires are often evaluated using frequent impacts. For example, frequent impacts were often presented to characterize the prevalence of important oral health problems (28, 29) or (only) frequent item responses were used in the calculation of OHIP summary scores (30, 31). Nevertheless, other thresholds could have been chosen. For example, in the above mentioned study by Nuttall et al. (32), authors counted also “occasional” impacts. Other studies used “frequent” impacts (33). For the purpose of identifying combinations of dimensions, the impact threshold is less relevant. Obviously, “frequent” impact is a subset of “any” impact. We were interested in whether a particular and substantial dimensional impact existed rather than how frequently it occurred. Using a lower threshold of impact would not change the principal findings that all combinations of the four dimensions were identified. Only the frequency of patterns would change. The absolute frequency for a dimensional impact pattern should also be interpreted with caution because it also depends on the number of items in the particular dimension, which can differ from one dimension to the other. Finally, we used OHIP to characterize OHRQoL dimensions, but we believe dimensional structure findings generalize well to other instruments measuring the same construct as discussed in previous work (2, 3).

Finally, we would emphasize again that this is a cross-sectional study. Consequently, we did not observe time nor a change in dimensions. Our patterns characterized a certain situation and it is not known which dimensional impact came first (for sets of two to four dimensional impacts) and whether, in addition to direct effects, indirect influences were also present. An individual could be just affected by the oral condition or could be affected for a long time. To improve our understanding of dimensional OHRQoL impacts, a longitudinal perspective would complement the presented cross-sectional findings.

Conclusions

Individuals perceive the impact of oral disorders and the effects of dental interventions in the dimensions of OHRQoL. In prosthodontics patients and general population subjects, this dimensional impact can occur in isolation, affecting only one of the four dimensions, but it can also be complex, influencing two, three, or even all four dimensions. While not all oral diseases will present all dimensional patterns, the presence of 16 dimensional response patterns can serve as a general framework for how important areas of perceived oral health are affected.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Andrea Medina (University of Minnesota) for her valuable comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DE022331.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest declared.

References

- 1.Gilbert GH, Duncan RP, Heft MW, Dolan TA, Vogel WB. Multidimensionality of oral health in dentate adults. Med Care. 1998;36:988–1001. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.John MT, Reissmann DR, Feuerstahler L, Waller N, Baba K, Larsson P, et al. Exploratory factor analysis of the Oral Health Impact Profile. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41:635–643. doi: 10.1111/joor.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John MT, Feuerstahler L, Waller N, Baba K, Larsson P, Celebic A, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Oral Health Impact Profile. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41:644–652. doi: 10.1111/joor.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.John MT, Reissmann DR, Feuerstahler L, Waller N, Baba K, Larsson P, et al. Factor analyses of the Oral Health Impact Profile - overview and studied population. J Prosthodont Res. 2014;58:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerritsen AE, Allen PF, Witter DJ, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NH. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:126-7525–8-126. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health. 1994;11:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szentpetery A, Szabo G, Marada G, Szanto I, John MT. The Hungarian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petricevic N, Celebic A, Papic M, Rener-Sitar K. The Croatian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile Questionnaire. Coll Antropol. 2009;33:841–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.John MT, Patrick DL, Slade GD. The German version of the Oral Health Impact Profile--translation and psychometric properties. Eur J Oral Sci. 2002;110:425–433. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2002.21363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rener-Sitar K, Celebic A, Petricevic N, Papic M, Sapundzhiev D, Kansky A, et al. The Slovenian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile Questionnaire (OHIP-SVN): translation and psychometric properties. Coll Antropol. 2009;33:1177–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsson P, List T, Lundstrom I, Marcusson A, Ohrbach R. Reliability and validity of a Swedish version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-S) Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62:147–152. doi: 10.1080/00016350410001496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamazaki M, Inukai M, Baba K, John MT. Japanese version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-J) Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2007;34:159–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2006.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker SR, Gibson B, Locker D. Is the oral health impact profile measuring up? Investigating the scale's construct validity using structural equation modelling. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:532–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mumcu G, Hayran O, Ozalp DO, Inanc N, Yavuz S, Ergun T, et al. The assessment of oral health-related quality of life by factor analysis in patients with Behcet's disease and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:147–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montero J, Bravo M, Vicente MP, Galindo MP, Lopez JF, Albaladejo A. Dimensional structure of the oral health-related quality of life in healthy Spanish workers. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.John MT. Exploring dimensions of oral health-related quality of life using experts’ opinions. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:697–704. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baba K, Igarashi Y, Nishiyama A, John MT, Akagawa Y, Ikebe K, et al. Patterns of missing occlusal units and oral health-related quality of life in SDA patients. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baba K, Igarashi Y, Nishiyama A, John MT, Akagawa Y, Ikebe K, et al. The relationship between missing occlusal units and oral health-related quality of life in patients with shortened dental arches. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:72–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim HY, Jang MS, Chung CP, Paik DI, Park YD, Patton LL, et al. Chewing function impacts oral health-related quality of life among institutionalized and community-dwelling Korean elders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:468–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inukai M, John MT, Igarashi Y, Baba K. Association between perceived chewing ability and oral health-related quality of life in partially dentate patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:118-7525–8-118. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sukumar S, John MT, Schierz O, Aarabi G, Reissmann DR. Location of prosthodontic treatment and oral health-related quality of life–An exploratory study. Journal of prosthodontic research. 2015;59:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahlström L, Carlsson GE. Temporomandibular disorders and oral health-related quality of life. A systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68:80–85. doi: 10.3109/00016350903431118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durham J, Steele JG, Wassell RW, Exley C, Meechan JG, Allen PF, et al. Creating a patient-based condition-specific outcome measure for Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs): Oral Health Impact Profile for TMDs (OHIP-TMDs) J Oral Rehabil. 2011;38:871–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2011.02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szentpetery AG, John MT, Slade GD, Setz JM. Problems reported by patients before and after prosthodontic treatment. Int J Prosthodont. 2005;18:124–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.John MT, Reissmann DR, Szentpetery A, Steele J. An approach to define clinical significance in prosthodontics. J Prosthodont. 2009;18:455–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2009.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brondani MA, MacEntee MI. Thirty years of portraying oral health through models: what have we accomplished in oral health-related quality of life research? Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1087–1096. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, Buelow JM, Otte JL, Hanna KM, et al. Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:134-7525–10-134. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schierz O, John MT, Reissmann DR, Mehrstedt M, Szentpetery A. Comparison of perceived oral health in patients with temporomandibular disorders and dental anxiety using oral health-related quality of life profiles. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:857–866. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durham J, Fraser HM, McCracken GI, Stone KM, John MT, Preshaw PM. Impact of periodontitis on oral health-related quality of life. J Dent. 2013;41:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen PF, Locker D. Do item weights matter? An assessment using the oral health impact profile. Community Dent Health. 1997;14:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moufti MA, Wassell RW, Meechan JG, Allen PF, John MT, Steele JG. The Oral Health Impact Profile: ranking of items for temporomandibular disorders. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119:169–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2011.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nuttall NM, Slade GD, Sanders AE, Steele JG, Allen PF, Lahti S. An empirically derived population-response model of the short form of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Jundi MA, Szentpetery A, John MT. An Arabic version of the Oral Health Impact Profile: translation and psychometric properties. International Dental Journal. 2007;57:84–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2007.tb00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]