Abstract

In the United States, state laws establish a minimum age of legal access (MLA) for most tobacco products at 18 years. We reviewed the history of these laws with internal tobacco industry documents and newspaper archives from 1860 to 2014.

The laws appeared in the 1880s; by 1920, half of states had set MLAs of at least 21 years. After 1920, tobacco industry lobbying eroded them to between 16 and 18 years. By the 1980s, the tobacco industry viewed restoration of higher MLAs as a critical business threat. The industry’s political advocacy reflects its assessment that recruiting youth smokers is critical to its survival.

The increasing evidence on tobacco addiction suggests that restoring MLAs to 21 years would reduce smoking initiation and prevalence, particularly among those younger than 18 years.

In the United States, state laws establish a minimum age of legal access (MLA) for tobacco. These laws first appeared in the 1880s, and by 1920, between 14 and 22 states had MLAs of 21 years (14 states explicitly at 21 years whereas 8 states restricted sales to “minors,” ranging from 14 to 24 years). As of 2015, 46 of 50 states and Washington, DC, had MLAs of 18 years, with the remaining 4 at 19 years. The 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act set a nonpreemptive national MLA of 18 years to be enforced by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and prohibited the FDA from setting a higher age.1 Between 2012 and October 2015, 93 localities raised their MLA to 21 years.2,3 In 2015, Hawaii raised its tobacco MLA to 21 years, effective in 2016.4

The tobacco industry claims to support restrictions on youth access to tobacco, but has consistently advocated against increasing the minimum age of legal access to 21 years5,6 to the point of denying that such laws ever existed.7 Increasing the MLA for tobacco to 21 years is feasible, was once the standard in one third of all states, and would reduce tobacco addiction and deaths.2

METHODS

We drew our data from internal tobacco industry documents and newspaper archives. Between August 2014 and March 2015, we searched the Truth Tobacco Documents Library (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu) by using a snowball strategy8 beginning with keywords (“age limits,” “minors”). We used information in the initial documents to refine search terms and dates. We used comparable search terms and the same time period to review newspaper databases (New York Times [1851–2003], Los Angeles Times [1881–1985], the Chronicling America archive, state government libraries) for information on dates that laws were passed, ages of minors covered by these laws, and arguments made in support and in opposition to them. We analyzed data from approximately 300 documents and newspaper articles dated between 1860 and 2015 by using an interpretive approach.9

RESULTS

By the late 1600s, there was widespread public awareness that those who used tobacco found it difficult to quit. In the 1700s, European studies reported that pipe smoking caused lip and throat cancers. The Bonsack cigarette-making machine, which reduced the cost of cigarette production, was patented in 1881.10 States began restricting the sale of tobacco to minors fearing that cigarettes, which could be sold individually and had become cheap, were uniquely appealing to children (see the box on the next page).11

Timeline of Health Knowledge of Tobacco, Tobacco Industry Activity, and Minimum Age of Legal Access Laws: United States

| late 1600s | Public awareness that tobacco use is addictive becomes widespread. |

| 1700s | European studies report that pipe smoking causes cancers of the lip and throat. |

| 1820s | German scientists isolate pure nicotine and identify it as a poison. |

| 1881 | James Bonsack’s cigarette-making machine is patented, with a production rate 500 times greater than hand laborers. |

| 1883 | New Jersey sets its minimum age of legal access (MLA) at 16 years. |

| 1886 | New York sets its MLA at 16 years; American Tobacco dramatically increases cigarette production with Bonsack machines. |

| 1890 | Twenty-six states and territories have set MLAs ranging from 14 to 24 years. |

| 1895 | States begin banning the sale of cigarettes entirely. |

| 1898 | German scientists hypothesize a link between tobacco and lung cancer. |

| 1904 | American Tobacco lobbyists are exposed bribing Indiana legislators to vote against a tobacco ban. |

| 1905 | American Tobacco arranges to have tabacum dropped from the US Pharmacopeoia. |

| 1906 | Tobacco is excluded from the Pure Food and Drug Act. |

| 1917 | Congress attempts to ban tobacco in the military; this effort is blocked by the tobacco industry. |

| 1918 | The War Department includes tobacco in soldiers’ daily rations. |

| 1920 | Forty-six of 48 states have set age limits on tobacco sales; South Carolina bans smoking in restaurants. |

| 1921 | Fifteen states have banned the sale of cigarettes since 1895; some bans have been overturned because of tobacco industry lobbying. |

| 1929 | First statistical evidence of a link between tobacco and lung cancer is reported. |

| 1939 | Last 2 states without age restrictions on tobacco sales pass laws: Ohio (18 years) and Rhode Island (16 years). |

| 1950s | Multiple states lower minimum age of legal access as tobacco marketing to children becomes widespread. |

| 1953 | Maryland repeals its MLA. |

| 1960s | Multiple states seek to increase, decrease, or overturn their MLAs. |

| 1963 | American Cancer Society suggests 18 years as an MLA; Alaska (18 years) and Hawaii (15 years) join the United States. |

| 1964 | Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health indicates that smoking causes lung cancer. |

| 1968 | Philip Morris studies seek to find the lowest politically feasible MLA. |

| 1971 | Lower MLAs are promoted by legislative advocates as a way to “ensure stricter enforcement” of tobacco laws. |

| 1985 | The American Medical Association proposes new restrictions on tobacco, including a national MLA of 21 years. |

| 1990 | The US Department of Health and Human Services proposes a model MLA set at 19 years. |

Tobacco Laws in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries

New Jersey forbade tobacco sales to those younger than 16 years in 1883,12 and New York in 1886 (except by written order of a parent or guardian) with legislators claiming that the progressive Women’s Christian Temperance Union would help enforce the law.13 In 1889, multiple states passed similar laws, including Connecticut,14 Michigan,15 and Oregon.14,16–18 The Salem Evening Capital Journal noted that,

tobacco dealers should take notice that the law has gone into effect and that they are now liable to prosecution for selling tobacco under any circumstances to minors.14(p4)

The belief by New York legislators that the Women’s Christian Temperance Union would help enforce cigarette laws was justified. The organization, best known for its efforts to pass the 18th Amendment to the Constitution banning alcohol sales, also opposed tobacco and gambling. With affiliated groups, it advocated laws that restricted the sale and use of cigarettes. By 1890, their efforts, combined with general distress over children smoking, led 26 states and territories to ban sale or use of cigarettes by minors, variously defined from those younger than 14 to 24 years.18–20

In the early 20th century, concerns about lax enforcement led to increasingly strict laws. The Los Angeles Times wrote in 1900 that,

There is scarcely a tobacconist in Los Angeles who does not violate [the statute prohibiting tobacco sales to those younger than 16 years] at least a dozen times a day, as it is notorious that youths of tender years form a large proportion of the great army of cigarette smokers. . . .21

The Times continued to write regularly on the use of tobacco by minors,22–24 reporting in 1908 that

Cigarette tobacco is very popular . . . it is not uncommon, it is said, to see a child not more than five years old smoking contentedly.25

California increased its MLA for tobacco from 16 to 18 years in 1911. Reporting on the legislation, the Times stated that

Radical changes were made, and dealers who have been making sales to youths upon the order of their parents or guardians, or upon the prescription of practicing physicians, may as well consign these orders to the scrap heap. . . . These orders may be genuine, and again the chances are good that many of them are spurious. In any event, the new law removes the temptation of procuring bogus orders.26

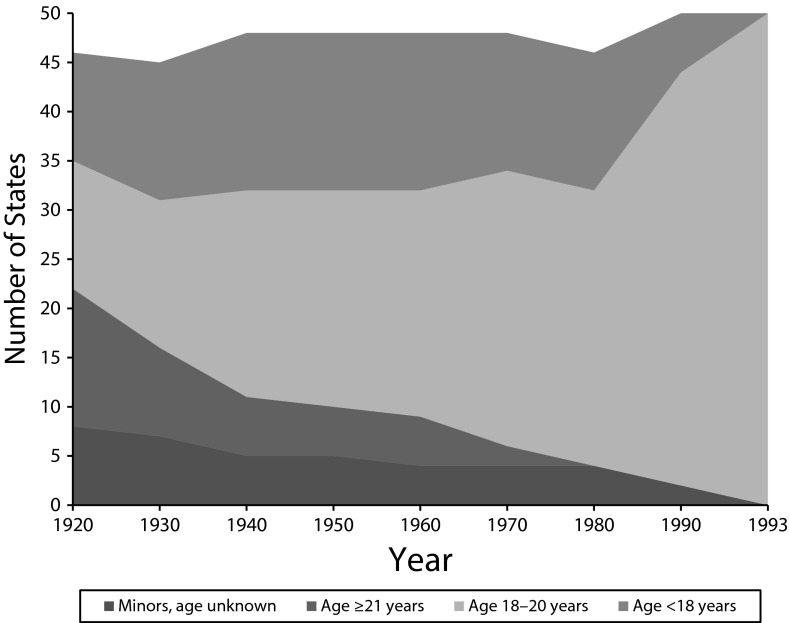

Between 1895 and 1921, 15 states banned the sale of cigarettes entirely.19 Although these statutes were repealed by 1927, restrictions on sales to minors remained and were steadily expanded.19 Until the 1940s, increasing numbers of states regulated the sale of cigarettes to minors and steadily increased their MLAs (Figure 1; states with bans were classified as having an MLA of at least 21 years). In 1920, when Oregon voters enacted a constitutional amendment banning tobacco altogether, South Carolina had banned smoking in restaurants, and 14 states had passed laws that prohibited the sale and advertisement of cigarettes.27 By the end of 1920, all but 2 states had enacted some kind of age limit on cigarette sales, and at least 14 had set an age limit of 21 years, with 8 more states limiting tobacco sales to “minors” without defining the term.

FIGURE 1—

State Minimum Ages of Legal Access to Tobacco: United States, 1920–1993

Note. The age at which minors in the United States could purchase cigarettes declined over the course of the 20th century; state minimum ages of legal access have remained at 18 or 19 years since 1993, although a minimum age of legal access of 21 years was enacted in Hawaii in 2015.

Cigarette manufacturers, at that time dominated by American Tobacco, developed extensive lobbying efforts against these new laws.11 Between 1890 and its court-ordered breakup in 1911, American Tobacco filed lawsuits challenging legislation that banned the sale of cigarettes, as well as recruited allies from the railroad industry, newspapers, and retailers to lobby on its behalf against license fees and tobacco bans.11 A historian of the Progressive Era noted in her book Cigarette Wars that the company had a reputation for attempting to bribe state legislators:

Yet another alleged attempt at bribery virtually forced the Indiana legislature to prohibit cigarette sales and manufacturing in 1904. Right before a critical vote in the House, Representative Ananias Baker dramatically held aloft a sealed envelope and announced that it had been given to him by a lobbyist from the “tobacco trust,” with instructions to vote against the bill. He opened it with a flourish: five $20 bills dropped out. It was widely assumed that similar envelopes had been distributed to other legislators. Baker left his colleagues little choice but to vote for the bill, lest their integrity be suspect.11(p35)

According to the Fort Collins Courier in 1920,

Action to forestall possible national legislation against the use of tobacco is being contemplated by producers in New England and elsewhere. . . . The Tobacco League of America, composed largely of Kentucky growers, with headquarters in Cincinnati, is likewise prepared to meet the “anti” forces with a heavy barrage. . . .27

The momentum to regulate tobacco faded after the United States entered World War I. Although Congress sought to ban tobacco in the military in 1917 on the grounds that it threatened the welfare of American troops, tobacco industry groups blocked the legislation by using organized letter-writing campaigns and press releases claiming that tobacco was an “absolute necessity” and that withholding it from soldiers would be “barbarous.”11 By 1918, the War Department included tobacco in soldiers’ daily rations, making the US government the world’s largest tobacco buyer.11 By the end of World War I, cigarette smoking had become widespread and socially accepted, even as medical evidence linking smoking to lung cancer was growing. In 1939, the longstanding holdouts of Ohio and Rhode Island set MLAs (of 18 and 16 years, respectively).

Reducing MLAs in the 1950s and 1960s

States chose different age limits when they first passed laws restricting the sale and use of tobacco and changed their MLAs over time. Illinois, for example, dropped its MLA from 18 to 16 years in 1920 then raised it to 18 years in 1964. By contrast, Iowa raised its MLA from 16 to 21 years in 1934 then reduced it to 18 years in 1964. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, legislators in multiple states repeatedly attempted to lower the minimum age of legal access to tobacco to 18 or 16 years, in some cases successfully. In 1953 and 1955, Maryland and Oregon temporarily repealed their prohibitions on selling cigarettes to minors. Between 1954 and 1963, 10 states lowered the age of access from 21 to 18 years (and 19 years in Utah).28–35 In the late 19th and early 20th century, higher age limits were viewed as a means of ensuring better enforcement; 50 years later, the press reported that lowered age limits were proposed as a means of ensuring “stricter enforcement.”36,37

In the 1950s, tobacco companies were openly marketing to children. In 1952, a California tobacco industry lobbyist, V. W. Miller, wrote RJ Reynolds suggesting that the company develop branded signs claiming that cigarettes were not sold to minors at the point of sale as a form of advertising in response to California laws prohibiting sales to those younger than 18 years.38 The company rejected this proposal to avoid “antagonizing” youngsters who would “sooner or later become . . . customers.”39

Tobacco companies also began devoting increasing resources to the sales of candy cigarettes.40 Beginning in 1953, Philip Morris arranged to have candy cigarettes distributed to children through its “Johnny Jr. Operation,” in which the company’s mascot distributed “candy Philip Morris 4s for children.”41 RJ Reynolds hosted tours of cigarette factories for school groups and scout troops with the expectation that the attendees would leave with a good image of the company.42–44 In a 1956 national sales meeting, American Tobacco representatives noted that, although college sales representatives were less productive than other employees, the company’s sampling programs at college campuses were an “excellent investment.”45 A 1961 marketing plan for Lorillard’s Spring cigarettes stated that those aged 15 to 24 years were the product’s “new market.”46 In 1962, students were recruited to represent tobacco companies and distribute samples on college campuses.47 Until 1963, multiple college newspapers were supported by revenues from cigarette advertisements and donations from the Tobacco Institute.48,49 All these programs explicitly targeted those younger than 21 years despite the fact that 5 states still had a minimum age of legal access for tobacco products of 21 years and 4 had ambiguous laws referring to “minors.”35

By the mid-1960s, several states were reconsidering the decisions to lower their MLAs. A 1963 paper by an American Cancer Society researcher in the Journal of Chronic Diseases noted that

18 years is the minimum age at which a substantial proportion of adults feel that a youngster might be permitted to choose his own course about smoking.50(p383)

Efforts to change MLAs were mentioned without comment in tobacco industry lobbyist reports tracking state legislative activity in 1959 and 1963.29,32 In 1963, attempts to raise the age of access back to 21 years in Massachusetts and Oregon failed at the same time that efforts to decrease the age of access from 21 years to 18 or 19 years were pending in Kansas, Michigan, Utah, Tennessee, and Washington.7,35,51,52 In 1960s and 1970s, 4 states—Colorado, Kentucky, Ohio, and Wisconsin—temporarily repealed their MLA laws.

These changes in state laws suggested that minimum ages could be lowered but not permanently eliminated. A 1968 public relations study for Philip Morris surveyed business leaders, theologians, academics, and newspaper editors in part to identify the lowest minimum age of legal access that would be politically feasible. Most respondents believed that 18 years was the youngest, although the survey proposed that respondents consider ages as low as 14 years.53 The study also polled a broader cross-section of respondents; of these

a majority (69%) of both smokers and nonsmokers feel that some minimum age limit for purchasing cigarettes should be strictly enforced.53(p9)

By 1969, an American Tobacco state legislative activities report mentioned that he industry “did not oppose” laws proposed to prohibit sales to minors younger than 18 years.54 However, industry lobbyists actively opposed proposals to restore the minimum age to 21 years, as well as any proposed legislation that would prohibit distribution of free cigarette samples to minors.54

The tobacco industry viewed state minimum ages of legal access to tobacco as onerous. A 1969 summary report on state legislation prepared by an American Tobacco lobbyist states that,

This summary of state legislative anti-tobacco proposals in 1969 clearly underscores the need for federal pre-emption of state and local action pertaining to the control and regulation of the advertising and distribution of cigarettes and other tobacco products.54(p61)

In 1971, a list of state minimum age laws compiled by the Tobacco Institute noted that,

In the last seven years, five States lowered the age at which the prohibition of sales to minors applies, usually in a context of ensuring stricter enforcement. Prior to that, six States had lowered the statutory age below which sales are prohibited from 21 to 18 or to 15.36(p1–2)

Tobacco Industry Resistance in the 1980s and 1990s

In the 1980s, the American Medical Association (AMA) and US Department of Health and Human Services viewed tobacco promotions targeting youths and the resulting youth tobacco use as an increasingly serious public health problem.55,56 In 1985, the AMA proposed new national restrictions on tobacco marketing, including increasing the national MLA to 21 years and banning vending machine sales.57,58

Tobacco companies viewed these proposals as a critical business threat. The 1986 Philip Morris 5-year corporate strategic plan noted in its “sociopolitical” section that “These [AMA] resolutions strike at the core of PM-USA’s business.”58(p9) The company was concerned that the combination of health concerns, tax increases, and decreasing social acceptability made tobacco use less appealing; moreover, because smoking initiation occurs at a young age and people smoke less as they age, recruitment of new, young smokers was the company’s highest priority.58 The report noted that “attitudes point to a reduction in peer pressure to smoke and continuing erosion in start rates for young adults.”57(pB5)

The tobacco industry’s market expansion historically depended on the industry’s ability to market to young adults, and through them, to younger smokers.59–61 The 1986 Philip Morris 5-year plan explained that

Raising the legal minimum age for cigarette purchaser [sic] to 21 could gut our key young adult market (17–20). . . . If we completely lost this market segment, it could cause nearly a $400 million drop in [sales]. Moreover 66% of all smokers begin smoking at or before age 18, 80% begin before age 21.62(p9)

Young adult smokers have the highest smoking rates of any age group in the United States, and the early years of smoking are critical to solidifying addiction.63–69 As a result, the Philip Morris 5-year plan stated that the company was willing to commit enormous resources to block the AMA’s proposals.

We regard the AMA’s action as a seminal event. . . . We will . . . create a force of lobbyists nationwide to insure [sic] through quiet persuasion that none of the AMA’s resolutions become law anywhere—especially the 21 year old minimum age and vending machine ban. We intend to see the AMA’s proposals die an unquiet death.62(p10)

Despite the AMA’s efforts, neither the federal government nor any state returned its MLA to 21 years. A 1986 strategy document written by the Ness Motley Law Firm for Philip Morris outlined the company’s lobbying efforts to forestall new tobacco control legislation. The firm explained that “Most state and local proposals are very onerous when first proposed . . . we are often able to change the final product.”58(p3)

The Tobacco Institute’s public position was that the tobacco industry did not engage in political activity supporting or opposing MLAs. When the United Press International reported in May 1987 that the Tobacco Institute supported a national minimum age, it responded that

The [Tobacco] Institute’s position on minimum age statutes for purchase or possession of tobacco products is that such statutes should be decided by state and local authorities. We neither oppose nor support them, and we do not suggest, endorse or oppose any specific minimum age.55

Proposals to increase MLAs grew more tentative over time. In 1990, the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General noted that enforcement of tobacco access laws was inadequate.56 In response, the Department of Health and Human Services proposed a model law for states that included an increase in the minimum age of access for tobacco to improve enforcement with a suggested age of 19 years, despite noting that “states may wish to consider age 21, because addiction often begins at ages 19 and 20, but rarely thereafter.”56(p2)

Throughout the 1990s, the tobacco industry continued to view the prospect of increased minimum age as a critical issue. A 1990 Tobacco Institute memo for its Executive Committee explained that

The so-called “issue of tobacco sales to minors” will continue to pose a threat to the industry in the areas of advertising, sampling, promotion, and sales.70(p2),71

Given that public opinion viewed restricting access to tobacco for minors as desirable, industry representatives at times found it difficult to take a position without further compromising the industry’s already limited popularity. In another memo, Tobacco Institute lobbyists suggested that

we gave up more than was necessary on [youth access] in 1991, therefore weakening potential PR value if we now come out in support of “youth purchase” laws.72(p9)

Another noted that “it is critical to advance our position that the tobacco industry believes that smoking is an adult custom and does not want minors to smoke.”73(p116)

In 1991, the Philip Morris 5-year corporate strategic plan proposed that the company take ownership of the minimum age issue by encouraging passage of a national minimum age of 18 years.73 Tobacco Institute lobbyists continued to monitor states that attempted to increase the minimum age above 18 years on a weekly, monthly, and quarterly basis.74,75 Despite the industry’s own records, which showed that the age of access had been 21 years in many states, industry representatives argued in radio programs and in press releases that any increase in MLAs was historically unprecedented.76

In 1992, Congress enacted the Synar Amendment in an effort to ensure that all states restricted the age of access to a minimum of 18 years by tying the receipt of Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant awards to enforcement of such laws.77 By 1993, all states had changed their MLAs to 18 or 19 years.

A Tobacco Institute 1998 public statement on age limits, which proposed industry-written legislation to states to permanently set MLAs to 18 years, conflated historical misrepresentation with claims that young adults were desperate to begin smoking:

The 18-year-old minimum sales age is appropriate and should not be changed. Eighteen-year-olds are deemed mature enough to serve in the military, to enter into contracts and to marry; and 18 typically is the age at which young people leave home for college. . . . Proposals to raise the minimum sales age simply do not address any “youth” issue—unless one adopts a new definition of “youths” to suit the occasion. . . . It is therefore difficult to see what purpose would served [sic] by raising the minimum sales age for tobacco. The main effect of doing so may simply be to drive 18–20 year-olds to find other means of obtaining tobacco, legal or illegal. . . . The 21-year-old minimum sales age for alcohol is an exception to the general rule that 18 is the age at which young people are treated as adults in our society [emphasis in original].7(p2)

The Tobacco Institute claimed that there was sufficient justification to retain a lower age limit indefinitely:

Under legislation passed by Congress in 1992, moreover, the states are encouraged to have in effect laws prohibiting the sale or distribution of tobacco products to persons under 18, and the FDA, in its tobacco rule, established 18 as the national minimum sales age [emphasis in original].7(p2)

In 1998 the Tobacco Institute continued to lobby in states that proposed to “increase smoking age to 21,” which at that point included Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, New York, Ohio, and Wisconsin, placing these states on its “problem” list.75 Lobbying reports written for Philip Morris between 1996 and 1999 explained that industry representatives were “proactively” opposing efforts to increase state MLAs as new proposals were drafted.78–80 By that time, many outside the industry no longer realized that MLAs had once been 21 years or more in many states.7

Resurrecting Higher MLAs in the 21st Century

Efforts to increase MLAs gained traction in the 21st century. In 2005, the board of health in Needham, Massachusetts, raised its MLA to 21 years with little media attention. Evidence showing that smoking rates in Needham had declined by 50% in the wake of the change led other Massachusetts localities to pass similar laws.81,82 Between 2012 and 2015, 93 localities in 7 states increased their MLAs from 18 to 21 years.83,84 These increases were opposed by Philip Morris and Lorillard, which actively lobbied against an effort to increase the MLA in Colorado, and against local proposals in Massachusetts, arguing that states and localities should wait for congressional or FDA action81 despite the fact that FDA is prohibited from increasing the MLA above 18 years.

DISCUSSION

Although MLAs greater than 18 or 19 years have been largely forgotten, they have extensive historical precedent. Restricting the sale and use of tobacco for individuals younger than 21 years was common throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the United States. During those years, higher MLAs were also viewed, with justification, as a means of improving enforcement of tobacco control laws.

Concern about smoking of cigarettes by youths, which in the late 19th century was observed in children aged as young as 5 years, triggered the first regulation of tobacco.25 In the Progressive Era, from the 1890s to the 1920s, laws restricting cigarette use mirrored laws restricting alcohol use, and 15 states banned the sale or possession of tobacco entirely. These laws were later overturned by courts (Washington state in 1893) or state legislatures (during the post–World War I smoking boom.)11 Cigarette MLAs, however, remained and expanded to other states. Unlike alcohol MLAs, tobacco MLAs declined throughout the 20th century because of aggressive tobacco industry lobbying. In 1992, the tobacco industry successfully used the federal government’s attempt to set a minimum MLA of 18 years through the Synar Amendment to get states to treat 18 years as the maximum age restriction.

The tobacco industry has made extensive efforts to maintain low MLAs for tobacco, arguing that proposals to increase MLAs are likely to face significant political opposition. In actuality, statutes increasing MLAs reflect broad public support.85

As the industry has known since at least the 1960s, raising tobacco MLAs would reduce tobacco use. Efforts in the 21st century to raise tobacco MLAs reflect increasing understanding of the process by which individuals become addicted to tobacco. Almost 90% of smokers begin using tobacco before the age of 21 years,60,86 and these years are associated with the transition from experimental or occasional smoking to daily smoking.82,87–89 Furthermore, young adult smokers aged 18 to 20 years often provide cigarettes to younger friends and family members.59 A 2015 Institute of Medicine report noted that an increase in tobacco MLAs to 21 years would reduce adult smoking prevalence by 12%, and an increase to 25 years would decrease prevalence by 16%, as well as reduce tobacco use by those aged 15 to 17 years.2

Our study has limitations. The Truth Tobacco Documents Library is not comprehensive, and is particularly limited between 1880 and 1920. Newspaper archives from this period are also incomplete. In multiple states, there was no record of how lawmakers defined the term “minor” at the time that laws were passed.

Throughout most of the 20th century, the tobacco industry aggressively encouraged and defended lowered MLAs for tobacco. This political advocacy reflects the tobacco industry’s assessment that recruiting youth smokers is critical to its economic survival. This assessment and the increasing body of evidence on tobacco addiction among young adults suggest that restoring MLAs to 21 years would reduce smoking initiation and prevalence, particularly in youths younger than 18 years.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grants (CA-140236, CA-87472, and CA-61021).

Note. The funder played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the article.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Human participants were not involved in the research reported in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, 21 USC §387f (2009).

- 2. Institute of Medicine. Public health implications of raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed]

- 3.Preventing Tobacco Addiction Foundation. Tobacco twenty-one. 2015. Available at: http://tobacco21.org. Accessed October 23, 2015.

- 4.Griggs B. Hawaii set to become first state to raise smoking age to 21. CNN. April 28, 2015. Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2015/04/27/us/hawaii-smoking-age-21-feat. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 5.Nelson S. Nationwide fight begins over raising tobacco age to 21. US News World Rep. October 31, 2013. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2013/10/31/nationwide-fight-begins-over-raising-tobacco-age-to-21. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 6.Caruso DB. Tobacco-buying age in NYC to be raised to 21 with new legislation. Huffington Post. November 19, 2013.

- 7. State Laws: Minors (Patti). Report. Tobacco Institute. August 28, 1998. Bates no. TI10371338. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zgv44b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 8.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control. 2000;9(3):334–338. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill M. Archival Strategies and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proctor RN. Golden Holocaust. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tate C. Cigarette Wars: The Triumph of “The Little White Slaver.”. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. New Jersey lawmaking. New York Times. March 13, 1883.

- 13. No tobacco for minors. New York Times. July 4, 1887.

- 14. Boys can’t buy tobacco. Evening Capital Journal. February 20, 1889.

- 15. The legislature: the session is rapidly drawing to a close. Evening Capital Journal. February 13, 1889.

- 16. No tobacco for minors. New York Times. March 22, 1889.

- 17. Michigan’s anti-tobacco legislation. Los Angeles Times. May 8, 1889.

- 18.Borio G. Tobacco timeline: the nineteenth century—the age of the cigar. In: The tobacco timeline. 1993. Available at: http://archive.tobacco.org/History/Tobacco_History.html. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 19.Alston LJ, Dupre R, Nonnenmacher T. Social reformers and regulation: the prohibition of cigarettes in the United States and Canada. Explor Econ Hist. 2002;39:425–445. [Google Scholar]

- 20. In the Supreme Court of the Hawaiian Islands. The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. September 23, 1897.

- 21. Protect the innocents. Los Angeles Times. July 26, 1900.

- 22. The cigarette boy. Los Angeles Times. November 28, 1911.

- 23. “The makings” cause arrests. Los Angeles Times. October 8, 1906.

- 24. Cigarettes and arrests. Los Angeles Times. October 2, 1906.

- 25. Lady nicotine tempts boys. Los Angeles Times. February 2, 1908.

- 26. Tobacco taboo under new law: dealers can’t sell or give it to minors; age is fixed at eighteen and heavy penalty imposed for violation when act becomes effective after next Tuesday. Los Angeles Times. May 21, 1911:sect 2.

- 27. Tobacco’s frends [sic] to fight “antis.” Fort Collins Courier. March 12, 1920.

- 28. Restrictive legislation affecting tobacco introduced in state legislatures. Tobacco Institute. October 1963. Bates no. TI06261575. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iwd55b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 29. Status of 1962 state tobacco legislation other than taxes. RJ Reynolds. 1963. Bates no. 500081536-500081538. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/suz89d00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 30.Tobacco Merchants Association. State legislative information bulletin. RJ Reynolds. February 11, 1959. Bates no. 501862717-501862721. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/giy29d00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 31.Tobacco Merchants Association. Sales to and smoking by minors. Tobacco Institute. February 6, 1959. Bates no. TI00150128. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sde14b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 32.Tobacco Merchants Association. State legislative information bulletin. RJ Reynolds. February 6, 1959. Bates no. 501862630-501862635. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ahy29d00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 33.Tobacco Merchants Association. Subject: sales to and smoking by minors. Tobacco Institute. April 2, 1969. Bates no. TI00150130-TI00150133. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eim69b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 34. History: age of tobacco purchase laws (state of Utah). Tobacco Institute. March 19, 1957. Bates no. TI31350178. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/btt45b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 35. State statutes prohibiting sale or gift of cigarettes to minors. Lorillard. April 25, 1963. Bates no. 03714636-03714643. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ftc71e00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 36.Tobacco Merchants Association. Special report: 47 states prohibit sales of cigarettes to minors and most ban sales of other tobacco products. March 2, 1971. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI54762520. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hkb68b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 37. New state law hits smoking by juveniles. Vernal Express. July 11, 1963;sect 1:8.

- 38.Miller V, Reynolds RJ. “There is a state law in California regarding sales to minors, which I am attaching to this letter.”. Letter. RJ Reynolds. January 24, 1952. Bates no. 500808204. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jzf69d00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 39.Sturmer F. “I have no doubt that we could get some long-lasting (practically permanent) point-of-sale advertising…”. Letter. RJ Reynolds. January 31, 1952. Bates no. 500808202. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hzf69d00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 40.Proctor RN. Candy Cigarettes. Golden Holocaust. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2011. pp. 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porterfield J. Subject: Johnny, Jr. Operation. Research. December 19, 1953. Bates no. 2010019434. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zrq76b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 42.Blakely L. We had 5,879 visitors this month.… Letter. RJ Reynolds. September 1, 1955. Bates no. 511366904-511366907. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/psz43d00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 43.Blakely L. The Prince Albert department had 62 visitors in September.… Report. RJ Reynolds. November 2, 1959. Bates no. 511367019-511367020. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ysz43d00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 44.Blakely L. The Prince Albert department had 697 visitors in November.… Report. RJ Reynolds. December 1, 1959. Bates no. 511367011-511367013. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wsz43d00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 45.JWG. Report on sales meeting held in New York office December 12, 13, 14 and 15, 1955. American Tobacco. January 25, 1956. Bates no. 991204483-991204517. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lyx41a00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 46.Ladd D. 1961 advertising plans for spring cigarettes. Research. Lorillard. February 1961. Bates no. 91523905-91524041. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uep76b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 47.Mooney E. “This letter will serve as authorization to select and employ a student representative(s) at the college(s) listed below.”. Letter. Brown & Williamson. August 28, 1962. Bates no. 621408030-621408050. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/loc01f00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 48.Crisp Crawford E. Tobacco Goes to College: Cigarette Advertising in Student Media, 1920–1980. Jefferson, NC: McFarland; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tobacco Institute moves to eliminate college ads. Utah Daily Chronicle. June 25, 1963.

- 50.Horn D. Behavioral aspects of cigarette smoking. J Chronic Dis. 1963;16:383–395. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(63)90115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tobacco Merchants Association. Tobacco tax guide: minors’ history. List. Tobacco Institute. August 1, 1993. Bates no. TI16980936-TI16980940. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wqy40c00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 52. States restricting sales of cigarettes to and use of cigarettes by minors. Report. Tobacco Institute. April 1969. Bates no. TITX0001448-TITX0001449. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/oli32f00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 53.Feinberg M, Katz M, Lefkowitz J, Thorner L. Appendix: Public relations study for Philip Morris, Inc. Report. Philip Morris. January 1968. Bates no. 2021280721-2021280870. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gzk71f00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 54.Welch F. Annual summary report on state legislative and packaging, weights & measures activities - 1969. Memorandum. American Tobacco. September 12, 1969. Bates no. 966020051-966020112. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/taj97h00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 55.Kloepfer B. Tobacco purchase/possession age limits. Research. Ness Motley Law Firm. June 29, 1987. Bates no. TIOK0021884. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hhq66b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 56. Model sale of tobacco products to minors control act: a model law recommended. Tobacco Institute. 1990. Bates no. TI06241291-TI06241299. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/htr82b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 57.Business Planning and Analysis. Philip Morris five year plan 1986–1990. Philip Morris. March 1986. Bates no. 2044799001-2044799142. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dxd12a00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 58. Sociopolitical strategy (draft 1/21/86). Research. Ness Motley Law Firm. January 21, 1986. Bates no. 2043440040-2043440049. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cnv56b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 59.DiFranza JR, Coleman M. Sources of tobacco for youths in communities with strong enforcement of youth access laws. Tob Control. 2001;10(4):323–328. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.4.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: US Surgeon General’s Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 61.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Center for Chronic Disease and Prevention Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Discussion draft sociopolitical strategy. Philip Morris. January 21, 1986. Bates no. 2043440040-2043440049. Available at: https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=zswh0127. Accessed April 22 2016.

- 63.Sepe E, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Smooth moves: bar and nightclub tobacco promotions that target young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):414–419. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schane RE, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Nondaily and social smoking: an increasingly prevalent pattern. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19):1742–1744. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ling PM, Neilands TB, Glantz SA. Young adult smoking behavior: a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):389–394.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry research on smoking cessation. Recapturing young adults and other recent quitters. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(5 pt 1):419–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):908–916. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Using tobacco-industry marketing research to design more effective tobacco-control campaigns. JAMA. 2002;287(22):2983–2989. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.22.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown-Johnson CG, England LJ, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Tobacco industry marketing to low socioeconomic status women in the U.S.A. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e139–e146. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boisse M. [Memo] to: Kurt Malmgren re: Draft overview of state “minors laws.” Tobacco Institute. 1990. Bates no. TI25262614. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wnk45b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 71.Berman M, Crane R, Hemmerich N. Running the Numbers. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University College of Public Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sales to minors. States are listed by category for sales. Tobacco Institute. 1991. Bates no. TI25262558. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cmk45b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 73. Philip Morris. Philip Morris USA five year plan 1991–1995. Philip Morris. 1995. Bates no. 2048980095-2048980289. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dfp92e00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 74. 1995 status report: on state tobacco legislation: cigarette excise taxes. Tobacco Institute. April 21, 1995. Bates no. TI38331165-TI38331177. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qoc53b00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 75. [Strategy chart] defensive. Philip Morris. June 1998. Bates no. 2077427438-2077427451. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/him79h00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 76. Radio TV reports: Jolly Ann Davidson interview. Transcript. Tobacco Institute. May 1951. Bates no. TMDA0009663-TMDA0009682. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nlg00c00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 77.Lempert LK, Grana R, Glantz SA. The importance of product definitions in US e-cigarette laws and regulations. Tob Control. 2014 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051913. Epub ahead of print December 14, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. State legislative assessment by issue and district. Report. Philip Morris. 1999. Bates no. 2064862388-2064862396. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sxi29h00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 79. 1997 draft forecast smoking restrictions (chart: states affected proactive/defensive). Tobacco Institute. 1997. Bates no. TI06292389-TI06292390. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xpx30c00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 80. Topic: corporate tax. Report. Philip Morris. February 1996. Bates no. 2078844353-2078844357. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ktv89h00. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 81. Mickle T. More cities raise tobacco age to 21; industry stands to lose $2 billion of sales, near term, if change is made nationally. Wall Street Journal. October 28, 2014. Available at: http://www.wsj.com/articles/more-cities-raise-tobacco-age-to-21-1414526579. Accessed May 12, 2016.

- 82.Kessel Schneider S, Buka SL, Dash K, Winickoff JP, O’Donnell L. Community reductions in youth smoking after raising the minimum tobacco sales age to 21. Tob Control. 2015 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052207. Epub ahead of print June 12, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Winickoff JP, Hartman L, Chen ML, Gottlieb M, Nabi-Burza E, DiFranza JR. Retail impact of raising tobacco sales age to 21 years. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):e18–e21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Winickoff JP, Gottlieb M, Mello MM. Tobacco 21—an idea whose time has come. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):295–297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1314626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Winickoff JP, McMillen R, Tanski S, Wilson K, Gottlieb M, Crane R. Public support for raising the age of sale for tobacco to 21 in the United States. Poster presentation at: American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference and Exhibition; October 11–14, 2014; San Diego, CA. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Mowery P, Brick P, Farrelly MC. Pathways to Established Smoking: Results From the 1999 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Washington, DC: American Legacy Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Park S, Weaver TE, Romer D. Predictors of the transition from experimental to daily smoking among adolescents in the United States. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2009;14(2):102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Colder CR, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Flaherty BP et al. The natural history of college smoking: trajectories of daily smoking during the freshman year. Addict Behav. 2006;31(12):2212–2222. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hassmiller KM, Warner KE, Mendez D, Levy DT, Romano E. Nondaily smokers: who are they? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1321–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]