Abstract

Background

In June 2012, Canada implemented new pictorial warnings on cigarette packages, along with package inserts with messages to promote response efficacy (i.e., perceived quitting benefits) and self-efficacy (i.e., confidence to quit). This study assessed smokers’ attention towards warnings and inserts and its relationship with efficacy beliefs, risk perceptions and cessation at follow-up.

Methods

Data were analysed in 2015 from a prospective online consumer panel of adult Canadian smokers surveyed every four months between September 2012 and September 2014. Generalized Estimating Equation models assessed associations between reading inserts, reading warnings and efficacy beliefs (self-efficacy, response efficacy), risk perceptions, quit attempts of any length, and sustained quit attempts (i.e., 30 days or more) at follow-up. Models adjusted for socio-demographics, smoking-related variables, and time-in-sample effects.

Results

Over the study period, reading warnings significantly decreased (p<0.0001) while reading inserts increased (p=0.004). More frequent reading of warnings was associated independently with stronger response efficacy (Boften/very often vs never=0.28, 95% CI: 0.11–0.46) and risk perceptions at follow-up (Boften/very often vs never=0.31, 95% CI: 0.06–0.56). More frequent reading of inserts was associated independently with stronger self-efficacy to quit at follow-up (Btwice or more vs none=0.30, 95% CI: 0.14–0.47), quit attempts (ORtwice or more vs none= 1.68, 95% CI: 1.28–2.19), and quit attempts lasting 30 days or longer (ORtwice or more vs none=1.48, 95% CI: 1.01 – 2.17).

Conclusions

More frequent reading of inserts was associated with self-efficacy to quit, quit attempts, and sustained quitting at follow-up, suggesting that inserts complement pictorial HWLs.

Introduction

Prominent pictorial health warning labels (HWLs) on tobacco packaging were first implemented in Canada in 2000, with more than 70 countries adopting them since then.1 Countries print HWLs on package exteriors; however, package inserts (i.e., small leaflets inside of packs) remain underutilized, even though tobacco companies have long used them for promotions.2 Canada is the only country to use inserts to supplement HWLs,3 providing an important case study for understanding whether inserts can help enhance pictorial HWL effects.

Background

Experimental and observational studies indicate that pictorial HWLs are more effective than text-only HWLs in increasing consumer understanding of smoking-related risks and promoting cessation-related behaviors.4–10 Pictorial HWLs appear to work, at least partly, because they are threatening.11 Reviews of threat appeals in general,12,13 as well as of smoking cessation campaigns14 and cigarette package HWLs,7,8 indicate that strong, threatening communications promote desired risk perceptions and behaviors to avoid risks. Nevertheless, threatening pictorial HWLs have been critiqued for not increasing response efficacy beliefs (e.g., benefits of quitting) or self-efficacy beliefs (e.g., perceived ability to quit).11,15

The extended parallel process model (EPPM) predicts that threatening messages will be most effective when both perceived threat is high and efficacy beliefs are strong.12,13 Some experimental evidence suggests that fear arousing pictorial HWLs with loss-framed messages generate stronger quit intentions amongst smokers with relatively high compared to low self-efficacy to quit,16,17 consistent with other framing research on smoking cessation.18 Research on gain-framed messages that promote response efficacy beliefs is more mixed.16,19–22 While studies have compared framing alternatives, research has not assessed HWLs with both efficacy and threat messages. According to EPPM, this message combination should be the most effective.

Whether fear arousing pictorial HWLs can be optimized by promoting efficacy beliefs generally remains unexplored. Interventions often promote quitting by increasing self-efficacy.23–26 Although HWLs with cessation resource information increase awareness and utilization of cessation resources,3,27–30 self-efficacy’s role in this process is not clear. No study of which we are aware has examined longitudinal changes in efficacy beliefs as a function of HWL policy.

Study context

In June 2012, Canada implemented 16 new pictorial HWLs on different smoking-related risks, along with eight new package inserts with coloured graphics (see Appendix) to replace text-only inserts used since 2000. Inserts were enhanced to emphasize benefits of quitting (i.e., response efficacy) and to provide behavioural recommendations and coping information that may promote self-efficacy to quit. This goes beyond providing a telephone number (i.e., quitline) and/or cessation resource website, which many countries include on HWLs. A brief research report indicates that Canadian smokers who read inserts were more likely to try to quit.3,31 However, this study did not assess the psychological mechanisms by which reading inserts influenced quitting nor did it assess sustained cessation attempts.

The current study aims to determine trends in smokers’ attention toward package inserts and pictorial HWLs, while also determining their effects on efficacy beliefs, risk perceptions, and cessation behaviour at follow-up. We hypothesize that reading inserts will be associated with stronger self-efficacy to quit at follow-up, while reading inserts and HWLs will be associated with stronger response efficacy at follow-up. Reading HWLs, but not inserts, should be associated with stronger risk perceptions. We also hypothesize that reading both inserts and HWLs will be associated with cessation behaviour at follow-up, with efficacy beliefs and risk perceptions mediating these associations. Finally, we assess whether associations between reading HWLs, reading inserts and cessation behaviour are moderated by efficacy beliefs, risk perceptions or quit intentions, and whether reading HWLs and inserts interact.

Methods

Sample

Data were analyzed in 2015 from an online consumer panel of Canadian residents purposively recruited by diverse methods to for Internet-based market research on key consumer segments (www.gmi-mr.com). Recruitment involved sending invitation emails to panelists of eligible age (18 – 64 years old) who were either known smokers or whose smoking status was unknown. Eligible panelists had smoked at least once in the prior month and more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Participant follow-up also involved email invitations. To address attrition and maintain sample sizes of approximately 1,000 participants at each wave, samples were replenished with eligible, new participants. From September 2012 to September 2014, seven waves of data were collected at four month intervals. Across waves, the survey response rate for panellists to whom study invitations were sent was 15% (range=8%–22%) with 57% follow-up (range=53%–62%). The current study used all data from the first six waves, as well as a longitudinal subsample of participants with two or more surveys (n=1,432 individuals, 4,734 observations).

Measures

All questions were asked at every wave, with “don’t know” recoded to missing unless otherwise specified.

Reading HWLs and inserts

Participants were asked: “In the last month, how often, if at all, have you read or looked closely at the warning labels on cigarette packages?” Response options (i.e., “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “often”, “very often”) were recoded, combining “often” and “very often” for adequate sample size in analyses. Participants were also asked: “In the last month, how often have you read the health warnings on the inside of cigarette packs?” Responses (i.e., “not at all”, “once”, “a few times”, “often”, “very often”) were recoded, combining the three highest categories for adequate sample size in analyses.

Efficacy beliefs

Self-efficacy to quit was measured by asking: “If you decided to give up smoking completely in the next 6 months, how sure are you that you would succeed?”32 with responses on a 1- to 9-point scale, using verbal anchors for every other option (i.e., not at all, a little, moderately, very much, extremely). Response efficacy was measured by asking: “How much do you think you would benefit from health and other gains if you were to quit smoking permanently in the next 6 months?”32 with the same response options.

Risk perceptions

Questions were combined on awareness of smoking-related diseases and perceived personal risk for these diseases. Awareness was assessed by asking participants to indicate which illnesses, if any, are caused by smoking, followed by a list of diseases shown in random order, including three (i.e., heart attacks, bladder cancer, and blindness) described on Canadian HWLs (responses=yes; no; don’t know). Personal risk was assessed by asking: “Let’s say that you continue to smoke the amount that you do now. How would you compare your own chance of getting [heart attacks/bladder cancer/blindness] in the future to the chance of a non-smoker?” with responses options from 1 (Just as likely) to 4 (Much more likely), with a “Don’t know” option.33 For the three diseases on HWLs, participants were classified into three levels: 0=“no” or “don’t know” response to awareness of the smoking-related disease; 1=“yes” to awareness, but either “don’t know” or “no” for increased personal risk for the disease; 2=“yes” to awareness and increased personal disease risk. These indicators were summed (range=0 to 6).

Quit attempts

Participants were classified as making a quit attempt if they no longer smoked at follow-up (and smoked at the prior wave) or if they reported attempting to quit in the prior four months.28,29 These participants were asked about the longest time quit during this period, and 30 days or more was classified as a sustained quit attempt, because longer abstinence predicts better cessation success.34–36

Covariates

Socio-demographic variables included sex, age, race (white vs. non-white), educational attainment (high school or less; some college or university; completed university or higher), and annual household income ($29,999 or less; $30,000 to $59,999; $60,000 or more). Smoking-related variables included intention to quit within six months (yes, no); daily or non-daily cigarette smoking; the Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) (range=0–6);37 and use of cessation resources in the prior four months through quitlines (yes, no) or websites (yes, no). To adjust for prior survey participation, a variable was created for the number of prior surveys to which the participant had responded (range=0–5).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using Stata, version 13. Chi-square tests assessed differences between subsamples with and without follow-up. Data from the first six surveys were analyzed using generalized estimating equation (GEE) models, treating data from each wave as a separate observation and using an exchangeable correlation matrix to adjust for repeated observations. Using all data from the first six waves, linear trends were assessed by regressing any reading of inserts and, separately, any reading of HWLs on survey wave. Additional analyses included only the followed-up subsample. Separate bivariate and adjusted linear GEE models were estimated for follow-up (i.e., t+1) reports of response efficacy, self-efficacy, and smoking risk perceptions, with these outcomes regressed on prior wave assessments (i.e., t) for reading HWLs, reading inserts, and covariates, including the dependent variable. Similarly, bivariate and adjusted logistic GEE models were estimated for having made an attempt to quit and, separately, making a sustained quit attempt over the follow-up period (i.e., t+1), regressing these outcomes on prior wave efficacy beliefs, risk perceptions, reading HWLs, reading inserts, and control variables. In the models regressing quit attempts on study variables, we conducted mediation analyses using the −khb command to test whether association between cessation behaviors at follow-up and reading inserts or HWLs was mediated by efficacy beliefs or risk perceptions.38 Multiplicative interactions between the dummy coded reading variables as well as between these variables and response efficacy, self-efficacy, risk perceptions (treated as continuous variables) and quit intentions were assessed separately in fully adjusted models. An overall F-test for differences across levels of the interaction term was assessed, and, if statistically significant, stratified analyses were conducted.

Sensitivity analyses

Because of the skewed distribution for response efficacy, all models were re-run after dichotomizing response efficacy (“extremely” vs lower; “very much” or higher vs lower). Self-efficacy responses were multimodal, so all models were re-run using a five-level variable that combined response options with verbal anchors and adjacent response options. Finally, because participants were from an undefined sampling frame, analyses were re-run, using weights based on the age, gender and educational profile of smokers in Canada;39 these weighted analyses admit inference in terms of the general population of Canadian smokers. To assess potential biases from differential attrition, propensity score analyses40 adjusted for the likelihood of survey completion at the person-wave level. The predicted probability from the propensity score model represents a measure of confounding against which the coefficients of interest are adjusted. This adjustment removes biases from imbalance in the propensity score model covariates (i.e., employment, marital status, number of online surveys and smoking in the prior four months, health status, reasons for quitting smoking) among participant groups (attrition participants versus non-attrition participants). The pattern of results from sensitivity analyses was consistent in direction, magnitude, and statistical significance of effects, although a few results from the weighted models became marginally non-significant.

Results

Sample characteristics

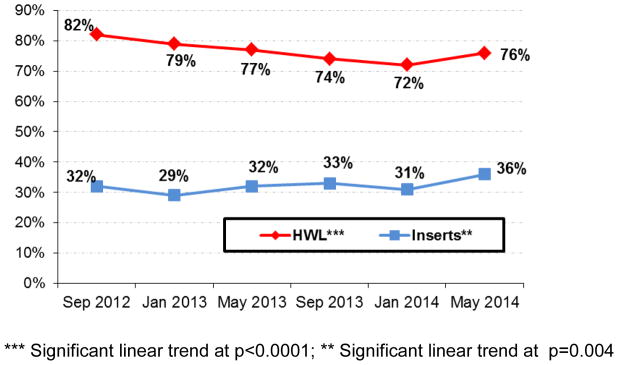

In addition to some socio-demographic and smoking-related differences between the follow-up sample (n=1,432 smokers, 4,734 observations) and smokers who participated in only one survey wave (n=1,748 smokers), smokers in the follow-up sample were more likely to report lower self-efficacy to quit, lower response efficacy, greater risk perceptions, and less frequent reading of HWLs and inserts (see Table 1). At each wave, 72% to 82% of the entire sample read HWLs in the prior month, with 29% to 36% reading inserts (Figure 1). In bivariate models with the entire sample, there was a significant linear trend indicating increased frequency of reading inserts over time (B=0.04, 95% CI 0.01–0.07; p=0.004), whereas reading HWLs decreased over time (B=−0.10; 95% CI −0.13– −0.07; p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics for Canadian smokers with and without follow-up data,* September 2012-September 2014

| Variable of Interest | Follow-up sample | No follow- up sample | Total Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agec | |||

| 18–24 | 7% | 21% | 12% |

| 25–34 | 20% | 28% | 23% |

| 35–44 | 22% | 22% | 22% |

| 45–54 | 25% | 16% | 21% |

| 55–64 | 26% | 14% | 22% |

| Sexc | |||

| Female | 51% | 61% | 55% |

| Educationc | |||

| High school or less | 27% | 39% | 31% |

| some College or University | 45% | 44% | 45% |

| University or more | 28% | 17% | 24% |

| Incomec | |||

| $29,999 or less | 24% | 32% | 26% |

| $30,000-$59,999 | 30% | 34% | 31% |

| $60,000 or more | 46% | 34% | 42% |

| Race | |||

| White | 85% | 84% | 85% |

| Non-White | 15% | 16% | 15% |

| Heaviness of Smoking Index | |||

| Mean (SE) | 2.4 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.6) |

| Cigarette consumptionb | |||

| Nondaily | 20% | 22% | 21% |

| Daily | 80% | 78% | 79% |

| Quit attempt in prior 4 monthsb | |||

| Yes | 41% | 44% | 42% |

| Quit Intentions in next 6 monthsc | |||

| Yes | 42% | 49% | 45% |

| Self-efficacyc | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.0 (2.1) | 5.3 (2.2) | 5.1 (2.2) |

| Response-efficacyc | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.4 (1.8) | 7.7 (1.7) | 7.5 (1.8) |

| Frequency of reading inserts in past monthb | |||

| Not at all | 72% | 68% | 71% |

| Once | 10% | 11% | 10% |

| A few times | 15% | 17% | 15% |

| Often | 2% | 3% | 3% |

| Very often | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Frequency of reading HWLs in past monthc | |||

| Never | 26% | 19% | 24% |

| Rarely | 35% | 32% | 34% |

| Sometimes | 26% | 28% | 26% |

| Often | 8% | 12% | 9% |

| Very often | 6% | 9% | 7% |

| Frequency of reading inserts in past monthb | |||

| Not at all | 72% | 68% | 71% |

| Once | 9% | 11% | 10% |

| Two or more times | 18% | 21% | 19% |

| Frequency of reading HWLs in past monthc | |||

| Never | 26% | 18% | 24% |

| Rarely | 35% | 32% | 34% |

| Sometimes | 26% | 28% | 26% |

| Often / very often | 14% | 22% | 16% |

| Risk Perceptionsc | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (2.0) | 3.0 (1.8) | 3.2 (1.9) |

| Called quitline in past four monthsb | |||

| Yes | 3% | 5% | 4% |

| Visited cessation website in past four months | |||

| Yes | 6% | 7% | 6% |

Seven survey waves were conducted every 4 months for two years. The follow-up sample included all individuals with two or more waves of data (nsmokers = 1,432 providing for 4,734 observations); the no follow-up sample included smokers who participated in only one wave (nsmokers = 1,748). 21% of smokers in the entire sample provided exactly two waves of data, and 29% of smokers more than two. Follow-up vs. no follow-up sample:

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

HWLs: Health warning labels

Figure 1. Reading HWLs and reading inserts in past month over the study period among all participants from wave-I to wave-VI.

Efficacy beliefs and risk perceptions at follow-up

In adjusted GEE models regressing follow-up self-efficacy on study variables (Table 2), reading inserts was independently associated with stronger follow-up self-efficacy (Bonce vs none=0.29, 95%CI 0.09–0.50; Btwice or more vs none= 0.30, 95%CI 0.14–0.47), but not with reading HWLs. In adjusted GEE models that regressed follow-up response efficacy on study variables (Table 2), more frequent HWL reading was associated with stronger follow up response efficacy (Boften/very often vs none= 0.28, 95%CI 0.11–0.46). In adjusted, but not bivariate models, reading inserts once in past month was associated with weaker response efficacy at follow-up (Bonce vs none=−0.18, 95%CI −0.36– −0.00). Adjusted GEE models that regressed follow-up risk perceptions on study variables (Table 2) indicated that reading HWLs, but not reading inserts, was independently associated with stronger follow-up risk perceptions (Brarely vs none = 0.19, 95%CI 0.01–0.36; Boften/very often vs none=0.31, 95%CI 0.06–0.56).

Table 2.

Predictors of efficacy beliefs and risk perceptions at follow-up, Canada, September 2012-September 2014

| Independent Variables | Self-efficacy at follow-up (t+1) | Response-efficacy at follow-up (t+1) | Risk Perceptions at follow-up (t+1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate Model Estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted Model~1 Estimate (95% CI) | Bivariate Model Estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted Model~2 Estimate (95% CI) | Bivariate Model Estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted Model~3 Estimate (95% CI) | |

| Reading Insert | ||||||

| Not at all | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Once | 0.25 [0.05 – 0.46] | 0.29 [0.08 – 0.50] | −0.15 [−0.34 – 0.04] | −0.18 [−0.36 – −0.00] | 0.06 [−0.14 – 0.27] | 0.05 [−0.17 – 0.28] |

| Two or more times | 0.37 [0.19 – 0.55] | 0.30 [0.14 – 0.47] | 0.10 [−0.05 – 0.25] | −0.09 [−0.24 – 0.05] | 0.20 [0.02 – 0.39] | 0.05 [−0.16 – 0.25] |

| Reading HWLs | ||||||

| Never | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Rarely | −0.11 [−0.27 – 0.05] | −0.14 [−0.30 – 0.02] | −0.01 [−0.15 – 0.13] | 0.07 [−0.06 – 0.20] | 0.22 [0.05 – 0.38] | 0.19 [0.01 – 0.36] |

| Sometimes | 0.06 [−0.12 – 0.24] | −0.16 [−0.33 – 0.02] | 0.08 [−0.08 – 0.24] | 0.13 [−0.01 – 0.27] | 0.26 [0.08 – 0.45] | 0.09 [−0.11 – 0.29] |

| Often/very often | 0.07 [−0.16 – 0.31] | −0.17 [−0.38 – 0.04] | 0.29 [0.11 – 0.48] | 0.28 [0.11 – 0.46] | 0.48 [0.26 – 0.69] | 0.31 [0.06 – 0.56] |

Models adjust for the independent variables listed in the table, as well as for age, gender, education, income, race, heaviness of smoking index, cigarette consumption, quit intention, quit attempts, using cessation resources (i.e., quitline or website) in previous four-months, visited cessation website in previous month, survey wave and time in sample

Model adjusted for self-efficacy at time ‘t’;

Model adjusted for response-efficacy at time ‘t’;

Model adjusted for both efficacy believes and risk perceptions at time ‘t’

HWLs: Health warning labels

Quit attempts at follow-up

Independent, positive associations with any follow-up quit attempt were found for self-efficacy (AOR=1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.12), response efficacy (AOR=1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.14), and more frequent reading of inserts (AORtwice or more vs none=1.68, 95% CI 1.28–2.19). Models for sustained quit attempts over the follow-up period found similar results for self-efficacy (AOR=1.14, 95% CI 1.05–1.24) and more frequent reading of inserts (AOR twice or more vs none=1.48, 95% CI 1.01–2.17). Quit intentions were positively associated with both making a quit attempt and making a sustained quit attempt.

Interactions between reading variables and efficacy beliefs, risk perceptions, and quit intentions were mostly not statistically significant (range p=0.057–0.814). For models predicting either quit attempt outcome, a statistically significant interaction was found between reading inserts and response efficacy (p=0.044 and p=0.032, respectively). After stratifying smokers into high and low response efficacy (i.e., “very much” or more; less than “very much”), independent associations were found for reading inserts and quit attempts of any length only amongst smokers with high response efficacy (AORtwice or more vs none=1.56; 95%CI=1.16–2.09). However, in the stratified models regressing sustained quit attempts on study variables, no statistically significant independent associations were found with reading inserts at either response efficacy level. In the sustained quit attempt model, a statistically significant interaction was found between reading inserts and risk perceptions (p=0.016). After stratifying smokers into high and low risk perceptions (using median risk perception), an independent association was found for reading inserts and sustained quit attempts amongst only smokers with low risk perceptions (AORtwice or more vs none=1.97; 95%CI=1.14–3.40]. In mediation analysis, neither efficacy beliefs nor risk perceptions mediated the relationship between reading HWLs or inserts and follow-up cessation behaviors (range p=0.194–0.695).

Discussion

This study suggests that reading cigarette package inserts with efficacy messages enhances follow-up self-efficacy to quit and promotes smoking cessation above and beyond reading pictorial HWLs on cigarette package exteriors. Reading inserts was associated not only with a greater likelihood of subsequent quit attempts, as in prior research,3 but also with sustained quit attempts that are more indicative of successful cessation.34–36 These associations were independent of reading HWLs, self-efficacy, response efficacy, and risk perceptions, with some indication that reading inserts was most effective for smokers with lower risk perceptions and higher response efficacy. Hence, inserts appear to complement threatening pictorial HWLs by influencing different smoker subpopulations and working along pathways that HWLs do not address. The relative importance of cessation messages on inserts was further suggested by higher rates of reading inserts (29%–36% across waves) than accessing cessation resources (3–6%).41 As expected, only reading inserts, not HWLs, was associated with self-efficacy at follow-up, providing evidence for the specificity of its effects.

Reading inserts was unassociated with response efficacy beliefs (i.e., benefits of quitting), contrary to hypotheses based on insert content. Compared to smokers who did not read inserts in the prior month, those who read them once had marginally lower downstream response efficacy, although only in adjusted models. No association was found with more frequent insert reading, suggesting that over-adjustment for potential confounders may account for this contradictory finding. By contrast, reading threatening pictorial HWLs was associated with stronger downstream response efficacy. Alongside the lack of support for mediation by either type of efficacy belief, this finding suggests that the effects of reading inserts on cessation behavior may be through pathways that we did not assess. Future research should consider enriched measurement of efficacy constructs to better reflect specific insert content. Improved understanding of the pathways through which inserts work should help with designing more effective content.

Reading HWLs was independently associated with stronger downstream response efficacy (i.e., beliefs about benefits of quitting) and risk perceptions, but not with cessation outcomes. Prior observational research with longer intervals between surveys (1–2 years) has also found that attention to HWLs, which includes reading HWLs, does not directly lead to downstream cessation,42 although attention promotes psychological elaboration of HWL messages that is associated with cessation.10,42 Similarly, prior research with our study sample found greater elaboration of HWL content appears to promote cessation attempts.3 Indeed, prominent pictorial HWLs, which cover 75% of Canadian cigarette packages, may promote cessation-related thoughts and behaviors independent of purposeful processing captured by self-reported HWL reading.

The salience of HWLs may explain the higher percentage of smokers who read HWLs (72%–82%) than inserts (29%–36%). The relatively low prevalence of reading inserts may also be due to message relevance, as only 42% of our sample intended to quit in the next six months, similar to other studies.35,43 Nevertheless, the percentage of smokers who read inserts increased over time, suggesting that their relevance can increase, even as attention to threatening pictorial HWLs declines. While other studies also have found evidence of wear out,44,45 this is the first to evince “wear in,” signifying the importance of future research in this area. Future research should examine the impact of different design features (e.g., colors; rotating designs) and message content (e.g., economic incentives to quit) that could promote attention to inserts and enhance their effects.46

Study results did not support hypotheses that reading pack inserts with efficacy messages would be most effective in promoting quit attempts for smokers who intend to quit, who have greater self-efficacy to quit, or who read HWLs more often. Prior research has not examined moderation of HWL message type by quit intention; however, experiments have found that loss-framing of pictorial HWLs appear more effective for influencing quit intentions amongst smokers with higher self-efficacy,16,17 whereas gain-frame text for pictorial HWLs is more effective for smokers with low self-efficacy. That we did not find evidence for moderation may be due to the more elaborated efficacy messaging on Canadian inserts, as well as the observational nature of our study. That efficacy and fear messages exhibit main, but not interactive effects, is consistent with prior research.12,13 Future research should examine how smokers with different levels of self-efficacy respond to diverse content and extent of efficacy message elaboration, whether through inserts or package HWLs.

Limitations

Self-reported reading variable may be biased, although correlations between these variables and related theory-based constructs in this and other studies support their validity. Furthermore, some smokers may have also considered inserts when responding to questions about HWLs. Nevertheless, discriminant validity is suggested by independent associations with theorized correlates (i.e., inserts with self-efficacy and HWLs with response efficacy and risk perceptions). Our single-item measures for efficacy beliefs may be limited, although they have been recommended for policy evaluation research,32 may be more accurate than multi-item measures,47 and show evidence of predictive validity.48 Nevertheless, future research may benefit from richer measurement that more tightly links question content with insert message content. We did not examine quit success because too few smokers successfully quit over the study period. By examining sustained cessation behavior (30 days or more), we advanced prior research that only assessed cessation attempts.3,10 Furthermore, our assessment of self-efficacy involved a key mediator of cessation success. Future research with larger sample sizes may be necessary to study quit success.

The study recruitment rate was low (12%). Although no data are available to directly assess selection bias, they may be similar to attrition biases. Attrition was associated with greater self-efficacy to quit, higher response efficacy, lower risk perceptions and more frequent reading of HWLs and inserts. Hence, we may have underestimated effects if smokers with these characteristics are more responsive to HWLs and inserts. However, sensitivity analyses to adjust for potential biases from differential attrition produced very similar results. Finally, our sample came from a consumer panel purposefully selected to represent the key market segments, but without a defined sampling frame. Lack of Internet access may not have substantially biased results, as 82% of Canadians are Internet users.49 Still, smoking is disproportionately concentrated among low socioeconomic groups,50 which also have lower Internet access. However, other research suggests that lower SES smokers are equally or more responsive to pictorial HWLs than higher SES smokers.51,52 Furthermore, analyses weighted to make our sample more similar to the general population of Canadian smokers produced similar results, suggesting our conclusions would not substantially change with a more representative sample. Even if our study population meaningfully differed from the general population, our longitudinal design with relatively short intervals between surveys (i.e., four months) advances prior research by allowing closer examination of how warning responses are associated with follow-up perceptions and behaviors. Prior observational studies have longer intervals between surveys (typically one to two years), allowing intervening variables, such as other tobacco control policies, to provide alternative explanations for study findings.

Conclusions

This study suggests that cigarette package inserts influence key psychosocial variables and promote sustained quitting behavior. Inserts have long been used by the tobacco industry, and the elaborated messaging inserts provide is commonly used in integrated marketing approaches to communicate with different consumer segments.53

Table 3.

Predictors of quit attempts and sustained quit attempts during follow-up period, Canada, September 2012-September 2014

| Quit attempt during follow-up | Sustained quit attempt during follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Independent Variables | 42% | Bivariate Model Estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted Model~ Estimate (95% CI) | 11% | Bivariate Model Estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted Model Estimate (95% CI) |

| Reading Insert | ||||||

| Not at all | 33% | REF | REF | 7% | REF | REF |

| Once | 51% | 1.39 [1.14 – 1.71] | 1.20 [0.89 – 1.62] | 12% | 1.65 [1.15 – 2.38] | 1.30 [0.83 – 2.03] |

| Two or more times | 61% | 1.91 [1.58 – 2.30] | 1.68 [1.28 – 2.19] | 16% | 2.07 [1.55 – 2.77] | 1.48 [1.01 – 2.17] |

| Reading HWLs | ||||||

| Never | 36% | REF | REF | 12% | REF | REF |

| Rarely | 36% | 0.87 [0.75 – 1.03] | 0.95 [0.75 – 1.18] | 9% | 0.79 [0.62 – 1.02] | 0.94 [0.64 – 1.38] |

| Sometimes | 47% | 1.08 [0.90 – 1.3] | 1.04 [0.79 – 1.36] | 12% | 0.90 [0.67 – 1.22] | 0.95 [0.61 – 1.46] |

| Often/very often | 56% | 1.38 [1.12 – 1.72] | 1.25 [0.90 – 1.73] | 15% | 1.15 [0.81 – 1.64] | 1.22 [0.73 – 2.04] |

| Quit Intentions in next 6-months | ||||||

| No | 24% | REF | REF | 5% | REF | REF |

| Yes | 62% | 2.65 [2.25 – 3.13] | 2.04 [1.66 – 2.51] | 14% | 2.44 [1.90 – 3.14] | 1.67 [1.20 – 2.33] |

| Self-efficacy at time ‘t’ | 1.16 [1.12 – 1.21] | 1.07 [1.02 – 1.12] | 1.27 [1.20 – 1.36] | 1.14 [1.05 – 1.24] | ||

| Response-efficacy at time ‘t’ | 1.10 [1.05 – 1.14] | 1.08 [1.02 – 1.14] | 1.11 [0.88 – 1.42] | 0.94 [0.86 – 1.03] | ||

| Risk perceptions at time ‘t’ | 1.00 [0.97 – 1.04] | 0.97 [0.92 – 1.02] | 0.95 [0.90 – 1.00] | 0.97 [0.902 – 1.046] | ||

Models adjust for the independent variables listed in table, as well as for age, gender, education, income, race, heaviness of smoking index, cigarette consumption, quit intention, quit attempts, using cessation resources (i.e., quitline or website) in previous four-months, survey wave and time in sample

HWLs: Health warning labels

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: This work was supported by the U.S. National Cancer Institute (R01 CA167067). The funding agency had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial disclosure: KMC has received grant funding from the Pfizer, Inc., to study the impact of a hospital based tobacco cessation intervention. KMC and DH receive funding as an expert witness in litigation filed against the tobacco industry. Authors JFT, KS, DA, DMK and JWH have no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society. Cigarette package warning labels: International status report. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt AM. The cigarette century. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thrasher JF, Osman A, Abad-Vivero EN, et al. The Use of Cigarette Package Inserts to Supplement Pictorial Health Warnings: An Evaluation of the Canadian Policy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17(7):870–875. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thrasher JF, Arillo-Santillan E, Villalobos V, et al. Can pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages address smoking-related health disparities? Field experiments in Mexico to assess pictorial warning label content. Cancer Causes & Control. 2012;23(Suppl 1):69–80. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9899-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang J, Chaloupka FJ, Fong GT. Cigarette graphic warning labels and smoking prevalence in Canada: a critical examination and reformulation of the FDA regulatory impact analysis. Tobacco Control. 2014;23(Suppl 1):i7–12. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond D, Thrasher J, Reid JL, Driezen P, Boudreau C, Santillan EA. Perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings among Mexican youth and adults: a population-level intervention with potential to reduce tobacco-related inequities. Cancer Causes & Control. 2012;23(Suppl 1):57–67. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9902-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tobacco Control. 2011;20(5):327–337. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noar SM, Hall MG, Francis DB, Ribisl KM, Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: a meta-analysis of experimental studies. Tobacco Control. 2015 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051978. Published Online First: 6 May 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond D, Reid JL. Health warnings on tobacco products: international practices. Salud Publica de Mexico. 2012;54(3):270–280. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342012000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yong HH, Borland R, Thrasher JF, et al. Mediational pathways of the impact of cigarette warning labels on quit attempts. Health Psychology. 2014;33(11):1410–1420. doi: 10.1037/hea0000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters GJ, Ruiter RA, Kok G. Threatening communication: a critical re-analysis and a revised meta-analytic test of fear appeal theory. Health Psychology Review. 2013;7(Suppl 1):S8–S31. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2012.703527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witte K. Fear control and danger control; a test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM) Communication Monographs. 1994;61:113–134. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education and Behavior. 2000;27(5):591–615. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durkin S, Brennan E, Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tobacco Control. 2012;21(2):127–138. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruiter RA, Kok G. Saying is not (always) doing: cigarette warning labels are useless. European Journal of Public Health. 2005 Jun;15(3):329. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mays D, Turner MM, Zhao X, Evans WD, Luta G, Tercyak KP. Framing Pictorial Cigarette Warning Labels to Motivate Young Smokers to Quit. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17(7):769–775. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romer D, Peters E, Strasser AA, Langleben D. Desire versus efficacy in smokers’ paradoxical reactions to pictorial health warnings for cigarettes. PloS One. 2013;8(1):e54937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van ’t Riet J, Ruiter R, Werrij M, Vries H. What difference does a frame make? Potential moderators of framing effects and the role of self-efficacy. European Health Psychologist. 2009;11:26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodall C, Appiah O. Adolescents’ perceptions of Canadian cigarette package warning labels: investigating the effects of message framing. Health Communication. 2008;23(2):117–127. doi: 10.1080/10410230801967825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nan X, Zhao X, Yang B, Iles I. Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels: examining the impact of graphics, message framing, and temporal framing. Health Communication. 2015;30(1):81–89. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.841531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toll BA, Rojewski AM, Duncan LR, et al. “Quitting smoking will benefit your health”: the evolution of clinician messaging to encourage tobacco cessation. Clinical Cancer Research. 2014;20(2):301–309. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao X, Nan X, Yang B, Alexandra lles I. Cigarette warning labels: graphics, framing, and identity. Health Education. 2014;114(2):101–117. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews JO, Felton G, Ellen Wewers M, Waller J, Tingen M. The effect of a multi-component smoking cessation intervention in African American women residing in public housing. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30(1):45–60. doi: 10.1002/nur.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandon TH, Tiffany ST, Obremski KM, Baker TB. Postcessation cigarette use: the process of relapse. Addictive behaviors. 1990;15(2):105–114. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90013-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cinciripini PM, Wetter DW, Fouladi RT, et al. The effects of depressed mood on smoking cessation: mediation by postcessation self-efficacy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(2):292–301. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Hea EL, Boudreaux ED, Jeffries SK, Carmack Taylor CL, Scarinci IC, Brantley PJ. Stage of change movement across three health behaviors: the role of self-efficacy. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2004;19(2):94–102. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.2.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavalcante TM. Labelling and packaging in Brazil. World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller CL, Hill DJ, Quester PG, Hiller JE. Impact on the Australian Quitline of new graphic cigarette pack warnings including the Quitline number. Tobacco Control. 2009;18(3):235–237. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.028290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thrasher JF, Pérez-Hernández R, Arillo-Santillán E, Barrientos-Gutierrez I. Towards informed tobacco consumption in Mexico: Effects of pictorial warning labels among smokers. Salud Pública de México. 2012;(54):242–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson N, Weerasekera D, Hoek J, Li J, Edwards R. Increased smoker recognition of a national quitline number following introduction of improved pack warnings: ITC Project New Zealand. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(Suppl):S72–77. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thrasher JF, Osman A, Abad-Vivero EN, et al. Are cigarette package inserts to supplement pictorial health warnings effective?: An evaluation of the Canadian policy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu246. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.IARC. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, Tobacco Control, Vol. 12: Methods for Evaluating Tobacco Control Policies. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costello MJ, Logel C, Fong GT, Zanna MP, McDonald PW. Perceived risk and quitting behaviors: results from the ITC 4-country survey. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2012;36(5):681–692. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.5.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dale LC, Olsen DA, Patten CA, et al. Predictors of smoking cessation among elderly smokers treated for nicotine dependence. Tobacco Control. 1997;6(3):181–187. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferguson JA, Patten CA, Schroeder DR, Offord KP, Eberman KM, Hurt RD. Predictors of 6-month tobacco abstinence among 1224 cigarette smokers treated for nicotine dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28(7):1203–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garvey AJ, Bliss RE, Hitchcock JL, Heinold JW, Rosner B. Predictors of smoking relapse among self-quitters: a report from the Normative Aging Study. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17(4):367–377. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90042-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the Heaviness of Smoking: Using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Addiction. 1989;84:791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohler W, Karlson B, holm A. Comparing coefficients of nested nonlinear probability models. The STATA Journal. 2011;11(3):420–438. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canadian Research Data Centre Network. [Accessed February 10, 2016];Canadian Community Health Survey. 2012 http://www.rdc-cdr.ca/datasets/cchs-canadian-community-health-survey.

- 40.Dorsett R. Adjusting for Nonignorable Sample Attrition Using Survey Substitutes Identified by Propensity Score Matching: An Empirical Investigation Using Labour Market Data. Journal of Official Statistics. 2010;26(1):105–125. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thrasher JF, Osman A, Moodie C, et al. Promoting cessation resources through cigarette package warning labels: a longitudinal survey with adult smokers in Canada, Australia and Mexico. Tobacco Control. 2015;24(e1):e23–31. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borland R, Wilson N, Fong GT, et al. Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: findings from four countries over five years. Tobacco Control. 2009;18(5):358–364. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.028043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prochaska JO, Norcross JC, Diclemente CC. Applying the stages of change. Psychother Aust. 2013;19(2):10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borland R, Yong HH, Wilson N, et al. How reactions to cigarette packet health warnings influence quitting: findings from the ITC Four-Country survey. Addiction. 2009;104(4):669–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, Cummings KM, McNeill A, Driezen P. Text and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: findings from the international tobacco control four country study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(3):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strahan EJ, White K, Fong GT, Fabrigar LR, Zanna MP, Cameron R. Enhancing the effectiveness of tobacco package warning labels: a social psychological perspective. Tobacco Control. 2002;11(3):183–190. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA. Dynamic self-efficacy and outcome expectancies: prediction of smoking lapse and relapse. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2005;114(4):661–675. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan M. Test-retest reliability and predictive validity for selected questions in the ITC Four Country Survey. ITC Project technical report. Canada: University of Waterloo; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.GMI. GMI Global Panel Book. Bellevue, WA: Global Market Insight, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reid JL, Hammond D, Driezen P. Socio-economic status and smoking in Canada, 1999–2006: has there been any progress on disparities in tobacco use? Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2010;101(1):73–78. doi: 10.1007/BF03405567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagelhout GE, Willemsen MC, de Vries H, et al. Educational differences in the impact of pictorial cigarette warning labels on smokers: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Europe surveys. Tobacco Control. 2015 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thrasher JF, Carpenter MJ, Andrews JO, et al. Cigarette warning label policy alternatives and smoking-related health disparities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43(6):590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krugman DM, Quinn WH, Sung Y, Morrison M. Understanding the role of cigarette promotion and youth smoking in a changing marketing environment. Journal of Health Communication. 2005;10(3):261–278. doi: 10.1080/10810730590934280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]