Abstract

Introduction:

Cigars remain a widely used tobacco product among adolescent and adult populations. The appeal of a certain type of cigar, the cigarillo, may be enhanced by users’ beliefs that their harm potential can be reduced by removing the inner tobacco liner before use (a.k.a. “hyping”). The purpose of this within-subject study was to compare the acute effects of smoking an original cigarillo, a modified (“hyped”) cigarillo, and an unlit cigarillo.

Methods:

Twenty smokers (19 males, 1 female; 19 non-Hispanic blacks, 1 Hispanic “other”) of at least 7 Black&Mild (B&M) cigarillos/week and at most 5 cigarettes/day completed the study. All participants reported hyping their cigarillos at least occasionally. Primary outcomes, assessed over two, 30-minute smoking bouts, included plasma nicotine, expired air carbon monoxide (CO) concentration, subjective ratings (product effects, nicotine abstinence symptoms), and puff topography.

Results:

Mean plasma nicotine concentration increased significantly within (pre- to post-bouts), but not between, original and modified B&M conditions. Mean CO concentration was significantly lower for modified, relative to original, B&M smoking at all post-administration timepoints. Both smoked conditions significantly increased ratings of positive product effects (satisfaction, pleasant) and decreased abstinence symptom magnitude; however, ratings generally did not differ between these conditions. Overall, topography outcomes did not differ between modified and original B&M smoking.

Conclusions:

Results are consistent with a previous report in that “hyping” may decrease users’ CO, but not nicotine, exposure. While these data collectively suggest reduced exposure to CO acutely with engagement in “hyping,” longer-term assessments are needed to determine the impact on individual and public health.

Introduction

Cigar products remain a widely used tobacco product among adolescent and adult populations in the United States. Past month use among middle and high school students is 2.8% and 12.6%, respectively.1 Among adults aged 18 or older, 12.8% reported current everyday use.2 Prevalence rates are even higher among those who also smoke cigarettes; as many as 42.6% of adolescent cigarette smokers and 10.6% of adult cigarette smokers report use of cigars.3–5 These prevalence rates may or may not include the use of all cigar types: small cigars, cigarillos, and large cigars. Small cigars most resemble a cigarette in terms of size, weight, and the inclusion of a filter.1 Cigarillos are classified as a large cigar based on their weight,6 though these products are longer, slimmer, and may have a wood or plastic tip.1 All of these cigar products, however, share certain characteristics that likely enhance their preference among users.

One appealing characteristic of cigars is their relatively low price. US excise taxes in many states are much lower for cigarillos and large cigars than for cigarettes.7 Additionally, flavors that are banned in cigarette products under the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, such as cherry or vanilla, are still permitted for cigar products.8 In fact, the flavor chemical profile for flavored tobacco products is similar to that for candy (eg, Swisher Sweet grape small cigars vs. Kool-Aid grape mix), and flavored tobacco products may also have higher levels of some flavor ingredients per serving.9 Importantly, users report that cigar products are appealing for reasons such as affordability and palatability, and these factors also predict their use.10–12

The appeal of cigars may also be enhanced by users’ belief that they are less lethal than cigarettes. Tobacco users have noted that the media warns only of the dangers of cigarette smoking.13,14 Thus, some may believe that the lack of anti-cigar messages signals the lack of adverse health risks associated with their use. Focus groups reveal some currently held beliefs about cigars: “(less) gas, toxic gases,…,” “natural,” “fresh”.13,14 Moreover, users of the Black&Mild (B&M) brand of cigarillos have been known to modify their product in the belief that doing so will reduce associated health risks. This behavior, known as “hyping” (a.k.a., “freaking,” “champing”),13,15 typically involves four steps: the tobacco filler is loosened, this filler is dumped out, the inner tobacco binder is removed, and the tobacco filler is dumped back into the leaf wrapper.16 The binder, referred to by users as the “cancer paper,”13 is removed prior to cigarillo use because “it cause(s) cancer,” “ruins the flavor,” and “causes the (cigarillo) to burn slower”.16 The extent to which smokers of cigarillo brands other than B&M, that also contain an inner liner, hold these same beliefs is unknown. Available work on this practice has reported only on use of the B&M brand.13,15–17 Either way, such beliefs for B&M cigarillos persist in the absence of any empirical evidence to support the notion that binder removal engenders these effects.

One published study has compared directly the effects of a cigarillo that is smoked in its original form versus after the binder has been removed.17 Smokers were required to have used B&M cigarillos in their lifetime, but were not required to report engagement in “hyping”. Following the ad libitum smoking of their condition-assigned product, expired air carbon monoxide (CO) levels were significantly lower for modified, relative to original, B&M smoking. Plasma nicotine levels were increased significantly from pre- to post-smoking for both B&M products, though did not differ between conditions. These results suggest that removal of the inner binder may, in fact, reduce exposure to some toxicants.17 On the other hand, participants may have changed the manner in which they smoke a B&M that is “hyped”. That is, they may have taken fewer (number), smaller (volume), shorter (duration), and/or more frequent (inter-puff-interval [IPI]) puffs from the modified cigarillos. Consequently, the amount of smoke toxicants delivered per puff may have been comparable between these conditions.

The purpose of this within-subject study was to compare the effects of smoking ad libitum an original B&M cigarillo, a modified B&M cigarillo (hyped), and an unlit B&M cigarillo (sham control). Each of these 2.5-hour conditions was preceded by overnight nicotine/tobacco abstinence and included the smoking of two of the condition-assigned products. Primary outcomes, assessed before and after each product use, included nicotine and CO delivery, and subjective ratings of product effects and withdrawal suppression. Additionally, smokers’ topography was assessed.

Method

Participants

Study participants, recruited by advertisements and word-of-mouth, included 19 men (18 non-Hispanic blacks; 1 Hispanic “other”) and one woman (non-Hispanic black) aged 18–35 years [mean (SD) = 24.6 (3.3) years]. Participants were required to report smoking at least seven B&M cigarillos per week [19.2 (15.8); range = 7–35], and no more than five cigarettes per day, for the past year. Of the 10 participants who reported current cigarette smoking, their average number smoked per week was 17.3 (16.4) (range 1–5 per day) for an average of 3.0 (3.5) years. Importantly, all participants reported current engagement in “hyping” their B&M cigarillos, even if only occasionally. We imposed this lenient criterion for inclusion given the lack of data available on “hyping” patterns for guidance. At screening, the average expired air CO level for all participants was 16.6 (9.3) parts per million (ppm). Exclusion criteria included self-reported chronic health or psychiatric conditions, regular use of medications (except vitamins or birth control), and pregnancy (verified via urinalysis) or breastfeeding.

Study Design and Procedures

In this within-subjects study, participants experienced three randomly ordered, 2.5-hour conditions: original B&M cigarillo smoking, modified B&M cigarillo smoking, or sham control (SHAM; puffing on an unlit B&M cigarillo). All conditions were separated by at least 48 hours and preceded by objectively-verified overnight tobacco abstinence (CO ≤ 10 ppm). Upon arrival to the laboratory, a catheter was inserted into a forearm vein for plasma sampling, and then continuous monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure commenced. Thirty minutes later, participants completed baseline measures of subjective effects, provided another CO sample, and had 10mL of blood collected. Next, participants used their condition-assigned product ad libitum for 30 minutes. Puff topography was measured via computerized device for the smoking of original and modified products, while sham smoking consisted of a directed smoking procedure (modified from18). Blood samples were collected again during the cigarillo bout, at 10 and 20 minutes after the onset of smoking. At the end of the 30-minute bout, participants completed measures of subjective effects, and provided CO and blood samples. These same procedures (baseline measures, 30-minute ad libitum cigarillo smoking with blood sampling and topography measurement, post-smoking measures) were repeated 30 minutes later for a second bout. The session then ended with catheter removal and participant payment ($50, $100, and $150 for sessions 1, 2, and 3, respectively). These procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Cigarillo Products and Smoking Procedures

The cigarillo brand used was B&M, which is the most highly preferred brand nationally across all age groups19 and also the only brand that cigarillo smokers appear to use for “hyping”. In all conditions, participants were provided with the B&M cigarillo of their preferred flavor (17 regular, 2 wine, 1 apple) and tip type (20 plastic).

For the modified B&M cigarillo condition, participants were required to “hype” their own cigarillos prior to the onset of session. Thus, participants were not blinded to study condition. Although participants’ proficiency with “hyping” was not documented in a formal manner, they were observed by experimenters during the process to ensure that they could, in fact, perform this behavior without problem. All participants were noted to engage in the four common steps previously reported in the literature: loosen the tobacco filler (eg, rolling between the hands), remove the loose filler, remove the inner liner, and replace the filler into the leaf wrapper.

Sham smoking is a commonly accepted negative control condition used to control for the motoric components of smoking. That is, sham smoking does not expose users to any tobacco toxicants (eg, nicotine, CO) or certain sensory stimuli (eg, smoke, taste). The directed smoking procedure ensures that participants engage in the process regularly throughout the 30-minute bout.20,21 For this study, participants were required to take at least 1 puff every minute for the entire 30-minute bout.

Physiological Measures

Expired air CO levels were measured via a BreathCo monitor (Vitalograph, Lenexa, KS). Blood samples were centrifuged and the plasma separated and stored at −70°C. Plasma was analyzed for nicotine using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry.18 Heart rate was measured every 20 seconds, and blood pressure every 5 minutes, via noninvasive computerized equipment (Model 507E, Criticare Systems).

Subjective Measures

Participants used a computer to respond to each of the four subjective measures, as described below.

Hughes–Hatsukami Withdrawal Scale

This scale was developed from the original22 questionnaire and consists of 11 visual analog scale items (Table 1) that measure individual nicotine/tobacco withdrawal symptoms. All items are presented as a word or phrase centered above a horizontal line that ranges from 0 (“not at all”) to 100 (“extremely”). The score for each item is the distance of the vertical mark from the left anchor, expressed as a proportion of the total length of the horizontal line.

Table 1.

Statistical Analysis Results for All Outcome Measures

| Conditiona | Boutb | Timec | Cond × bout | Cond × time | Bout × time | Cond × bout × time | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | |

| Physiological measures | ||||||||||||||

| Plamsa nicotined | 28.3 | <.001 | 21.8 | <.001 | 49.2 | <.001 | 8.6 | <.01 | 20.7 | <.001 | 3.8 | <.05 | 1.1 | ns |

| Heart ratee | 12.7 | <.001 | 11.5 | <.01 | 25.5 | <001 | 3.7 | <.05 | 16.8 | <.001 | 3.3 | <.05 | 3.3 | <.05 |

| COf | 41.7 | <.001 | 85.5 | <.001 | 87.6 | <.001 | 48.6 | <.001 | 52.2 | <.001 | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns |

| Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scalef | ||||||||||||||

| Anxious | 1.7 | ns | 8.5 | <.01 | 5.2 | <.05 | <1.0 | ns | 3.4 | <.05 | 4.5 | <.05 | 1.2 | ns |

| Craving | 23.4 | <.001 | 4.7 | <.05 | 25.8 | <.001 | 8.0 | <.01 | 6.2 | <.01 | <1.0 | ns | 2.1 | ns |

| Depression/feeling blue | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 4.2 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 2.5 | ns | 4.9 | <.05 | 1.7 | ns |

| Desire for sweets | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 4.4 | ns | 1.2 | ns | 1.2 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 1.8 | ns |

| Difficulty concentrating | <1.0 | ns | 10.7 | <.01 | 6.0 | <.05 | 1.4 | ns | 1.9 | ns | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns |

| Drowsiness | 1.1 | ns | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 1.2 | ns | <1.0 | ns |

| Hunger | <1.0 | ns | 2.8 | ns | 4.7 | <.05 | <1.0 | ns | 1.1 | ns | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns |

| Impatient | 1.2 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 3.4 | ns | 2.3 | ns | 1.6 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 1.5 | ns |

| Irritability/frustration/anger | 3.6 | ns | 1.6 | ns | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 2.1 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 1.2 | ns |

| Restlessness | 1.3 | ns | 2.6 | ns | 2.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 1.4 | ns | <1.0 | ns |

| Urges to smoke | 15.8 | <.001 | 11.4 | <.01 | 21.2 | <.001 | 1.4 | ns | 10.6 | <.01 | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns |

| Tiffany–Drobes Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Brieff | ||||||||||||||

| Factor 1 | 26.7 | <.001 | 32.9 | <.001 | 17.0 | <.01 | 15.1 | <.001 | 12.9 | <.001 | 1.5 | ns | 1.6 | ns |

| Factor 2 | 7.7 | <.01 | 6.8 | <.05 | 4.9 | <.05 | 7.5 | <.01 | 7.9 | <.01 | <1.0 | ns | 1.9 | ns |

| Direct effects of tobaccof | ||||||||||||||

| Was the B&M satisfying? | 28.4 | <.001 | 13.7 | <.01 | 52.6 | <.001 | 5.2 | <.05 | 14.0 | <.001 | 14.1 | <.01 | 8.2 | <.01 |

| Was the B&M pleasant? | 28.6 | <.001 | 22.5 | <.001 | 39.0 | <.001 | 8.8 | <.01 | 10.9 | <.001 | 20.3 | <.001 | 7.3 | <.01 |

| Did the B&M taste good? | 11.5 | <.01 | 21.1 | <.001 | 45.8 | <.001 | 5.2 | <.05 | 13.0 | <.001 | 28.0 | <.001 | 3.3 | <.05 |

| Did the B&M make you dizzy? | 4.2 | <.05 | 3.0 | ns | 12.1 | <.01 | <1.0 | ns | 6.3 | <.01 | 4.3 | ns | 1.6 | ns |

| Did the B&M calm you down? | 12.2 | <.001 | 5.0 | <.05 | 26.7 | <.001 | 3.7 | <.05 | 8.5 | <.01 | 27.5 | <.001 | 5.3 | <.05 |

| Did the B&M help you concentrate? | 6.0 | <.05 | 6.2 | <.05 | 10.5 | <.01 | 1.8 | ns | 4.5 | <.05 | 10.5 | <.01 | 5.3 | <.05 |

| Did the B&M make you feel more awake? | 8.8 | <.01 | 9.0 | <.01 | 16.5 | <.01 | 2.2 | ns | 5.9 | <.01 | 8.8 | <.01 | 2.6 | ns |

| Did the B&M reduce your hunger for food? | 5.2 | <.05 | <1.0 | ns | 15.1 | <.01 | <1.0 | ns | 2.9 | ns | 12.4 | <.01 | 3.6 | <.05 |

| Did the B&M make you sick? | <1.0 | ns | 2.7 | ns | 2.6 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 1.1 | ns | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns |

| Did the product taste like your own brand of B&M? | 9.1 | <.01 | 27.0 | <.001 | 42.1 | <.001 | 4.5 | <.05 | 11.9 | <.001 | 36.4 | <.001 | <1.0 | ns |

| Did the product feel like your own brand of B&M? | 16.8 | <.001 | 22.7 | <.001 | 30.7 | <.001 | 4.1 | <.05 | 11.1 | <.001 | 41.0 | <.001 | 5.5 | <.01 |

| Did the product feel as harsh as your own brand of B&M? | 13.1 | <.001 | 21.5 | <.001 | 21.4 | <.001 | 5.2 | <.05 | 12.5 | <.001 | 22.0 | <.001 | 3.4 | <.05 |

| Did the product feel as mild as your own brand of B&M? | 14.7 | <.001 | 35.4 | <.001 | 27.5 | <.001 | 5.5 | <.01 | 14.0 | <.001 | 21.8 | <.001 | 4.5 | <.05 |

| Would you like to smoke another B&M right now? | <1.0 | ns | 2.6 | ns | 14.7 | <.01 | <1.0 | ns | 4.0 | <.05 | 29.2 | <.001 | 1.9 | ns |

| Smoking topographyg | ||||||||||||||

| Number | 8.8 | <.01 | 1.1 | ns | <1.0 | ns | ||||||||

| Average volume | 6.9 | <.01 | 1.3 | ns | 1.6 | ns | ||||||||

| Total volume | 18.2 | <.001 | 1.7 | ns | 1.8 | ns | ||||||||

| Duration | 3.9 | <.05 | 2.2 | ns | 2.5 | ns | ||||||||

| Peak | 23.1 | <.001 | 1.5 | ns | <1.0 | ns | ||||||||

| Inter-puff-interval | 61.5 | <.001 | <1.0 | ns | <1.0 | ns | ||||||||

| Amount product usedh | 3.1 | ns | <1.0 | ns | 1.7 | ns | ||||||||

B&M = Black&Mild; CO = carbon monoxide; ns = nonsignificant. Statistical analysis results for the Direct Effects of Nicotine Scale items were exluded due to the lack of significant main and interaction effects.

aCondition factors: 3 (original, modified, and sham B&M smoking).

bBout factors: 2 (1, 2).

cTime factors: levels vary according to measure.

d df condition = (2, 36); df bout = (1, 18); df time = (3, 54); df cond × bout = (2, 36); df cond × time = (6, 108); df bout × time = (3, 54); df cond × bout × time = (6, 108).

e df condition = (2, 36); df bout = (1, 18); df time = (2, 36); df cond × bout = (2, 36); df cond × time = (4, 72); df bout × time = (2, 36); df cond × bout × time = (4, 72).

f df condition = (2, 36); df bout = (1, 18); df time = (1, 18); df cond × bout = (2, 36); df cond × time = (2, 36); df bout × time = (1, 18); df cond × bout × time = (2, 36).

g df condition = (2, 32); df bout = (1, 16); df cond × bout = (2, 32).

h df condition = (1, 18); df bout = (1, 18); df cond × bout = (1, 18).

Tiffany–Drobes Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Brief

The Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Brief23 consists of 10 Likert-scale items (Table 1) rated on a 7-point scale (0 = “Strongly disagree” to 6 = “Strongly agree”). Items were collapsed into two factors, previously defined by factor analysis: “intention to smoke” (Factor 1) and “anticipation of relief from withdrawal” (Factor 2). Factor 1 scores range from 0 to 30, while Factor 2 scores range from 0 to 24.

Direct Effects of Tobacco Scale

This visual analog scale measure was developed to assess the subjective effects of smoking tobacco.20,24 Fourteen items were included in this study (Table 1), though items were modified such that the word “cigarette” was replaced with “B&M.”

Direct Effects of Nicotine Scale

This visual analog scale consisted of items chosen to measure nicotine-related side effects.20,21,25 Ten items were included in this study: confused, dizzy, excessive salivation, headache, heart pounding, lightheaded, nauseous, nervous, sweaty, and weak.

Product Use Measures

Smoking Topography

Smoking topography was measured using the desktop version of the Clinical Research Support System (Borgwaldt, KC, Richmond, VA). To ensure direct contact with the participants’ lips, thus simulating real-world B&M use, the plastic tip of the cigarillo was placed on the proximal end of the device mouthpiece. The cigarillo rod was placed on the distal end of this same mouthpiece, which was adapted to fit the wider circumference of a cigarillo. Inhalation-induced changes in pressure were amplified, digitized, and sampled at 1000 Hz, and then converted to air flow (mL/s) using software (Borgwaldt, KC). Topography indices of puff number, volume (mL), duration (seconds), IPI (seconds), and peak (maximum value, mL/s) were produced.

Amount Smoked

Cigarillos were weighed before and after each smoking bout for the original and modified conditions. The difference in weight is expressed in grams.

Data Preparation and Analysis

Data for a single participant were removed from all analyses due to baseline plasma nicotine values for two conditions (7.2 and 15.9ng/mL) that suggested noncompliance with the overnight nicotine/tobacco abstinence requirement. Two additional participants were removed from the smoking topography analyses due to device malfunctioning during the original B&M condition. Thus, analyses reported here are based on 17 completers for smoking topography outcomes, and 19 completers for all other outcomes.

Plasma values below the limit of quantification were replaced with values of 2.0ng/mL. For plasma measures, the timepoints were baseline and 10, 20, and 30 minutes post-smoking onset for both bouts. Data for heart rate were averaged into the following bins for each smoking bout: 5 minutes prior to cigarillo administration (baseline), as well as 5 and 25 minutes post-smoking onset. Expired air CO and subjective measure timepoints included 5 minutes prior to cigarillo administration (baseline) and 5 minutes post-cigarillo use (ie, 5 minutes after the 30-minute smoking bout ended). Data for these aforementioned measures were analyzed using a condition (original, modified, sham) by bout (1, 2) by time (levels varied by measure) repeated-measures analysis of variance. Topography data were averaged within smoking bouts to obtain a single value for each variable and analyzed using condition (original, modified, sham) and bout (1, 2) as the within-subject factors. Huynh–Feldt corrections were used to adjust for violations of the sphericity assumption.26 Differences between means were examined using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference.27 Comparisons for which P < .05 are reported as significant.

Results

Statistical analysis results are displayed in Table 1. Means (±standard error of the mean [SEM]) for main effects are presented in Table 2; where appropriate, means (±SEM) for interaction effects are described in the text below. No main or interaction effects for the Direct Effects of Nicotine Scale items were observed to be significant, and thus these items are excluded from both tables.

Table 2.

Means (±1 SEM) for Main Effects for All Outcome Measures

| Condition | Bout | Timea | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | Modified | Sham | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Physiological measures | |||||||||||||

| Plasma nicotine (ng/mL) | 11.9 (0.8) | 10.6 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.0) | 6.9 (0.6) | 9.4 (0.6) | 2.0 (0.0) | 11.3 (1.6) | 8.2 (1.1) | 6.2 (0.7) | 4.2 (0.5) | 12.0 (1.3) | 11.4 (1.3) | 10.1 (1.2) |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 71.9 (0.8) | 71.1 (0.8) | 64.4 (0.6) | 69.8 (0.6) | 68.5 (0.6) | 66.6 (0.6) | 71.5 (0.8) | 69.3 (0.8) | |||||

| CO (ppm) | 19.3 (1.5) | 14.1 (0.9) | 5.1 (0.2) | 9.5 (0.9) | 16.1 (1.3) | 5.8 (0.3) | 13.3 (1.1) | 12.5 (1.0) | 19.7 (1.9) | ||||

| Hughes–Hatsukami Withdrawal Scale | |||||||||||||

| Anxious | 17.9 (3.6) | 20.4 (3.9) | 26.4 (4.3) | 24.4 (3.3) | 18.9 (3.1) | 30.1 (5.0) | 18.6 (4.2) | 20.5 (4.6) | 17.2 (4.1) | ||||

| Craving | 33.2 (4.0) | 34.8 (4.1) | 58.5 (4.5) | 45.1 (3.6) | 39.2 (3.6) | 52.1 (5.2) | 38.2 (4.7) | 46.5 (5.1) | 31.9 (4.8) | ||||

| Depression/feeling blue | 9.7 (2.6) | 6.9 (2.1) | 7.7 (2.2) | 8.3 (1.9) | 7.9 (1.8) | 8.5 (2.8) | 8.1 (2.6) | 10.0 (2.8) | 5.8 (2.2) | ||||

| Desire for sweets | 18.3 (3.7) | 16.8 (3.5) | 15.8 (3.5) | 16.7 (2.9) | 17.2 (2.9) | 17.7 (4.2) | 15.7 (4.1) | 17.4 (4.2) | 16.9 (4.1) | ||||

| Difficulty concentrating | 12.5 (2.7) | 11.8 (2.2) | 12.0 (2.8) | 13.3 (2.2) | 10.9 (2.0) | 16.8 (3.4) | 9.9 (2.8) | 12.8 (3.0) | 9.0 (2.7) | ||||

| Drowsiness | 21.1 (3.5) | 22.3 (3.6) | 27.6 (4.1) | 24.2 (3.0) | 23.1 (3.1) | 23.1 (4.3) | 25.4 (4.3) | 25.8 (4.4) | 20.4 (4.3) | ||||

| Hunger | 33.3 (4.1) | 33.1 (4.0) | 30.2 (4.0) | 29.5 (3.2) | 34.9 (3.3) | 26.5 (4.4) | 32.4 (4.6) | 34.2 (4.8) | 35.7 (4.7) | ||||

| Impatient | 14.5 (2.9) | 14.4 (2.8) | 20.1 (3.8) | 16.6 (2.6) | 16.0 (2.7) | 19.1 (3.8) | 14.1 (3.6) | 16.8 (3.9) | 15.2 (3.7) | ||||

| Irritability/frustration/anger | 10.3 (2.5) | 10.7 (2.5) | 19.3 (3.5) | 14.4 (2.4) | 12.4 (2.3) | 15.0 (3.3) | 13.8 (3.4) | 12.4 (3.4) | 12.4 (3.3) | ||||

| Restlessness | 10.4 (2.2) | 14.3 (2.9) | 16.3 (3.1) | 15.2 (2.4) | 12.1 (2.1) | 17.9 (3.7) | 12.5 (3.0) | 12.3 (3.0) | 11.9 (3.0) | ||||

| Urges to smoke | 31.8 (3.8) | 36.0 (4.2) | 58.8 (4.3) | 46.6 (3.5) | 37.9 (3.5) | 53.6 (5.0) | 39.6 (4.8) | 44.3 (4.9) | 31.4 (4.9) | ||||

| Tiffany–Drobes Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Brief | |||||||||||||

| Factor 1 | 12.5 (1.1) | 13.7 (1.1) | 21.1 (1.0) | 17.4 (0.9) | 14.2 (1.0) | 20.0 (1.2) | 14.8 (1.3) | 16.1 (1.3) | 12.3 (1.4) | ||||

| Factor 2 | 6.4 (0.8) | 6.4 (0.7) | 9.1 (0.9) | 7.7 (0.7) | 6.8 (0.7) | 8.3 (0.9) | 7.1 (1.0) | 7.5 (1.0) | 6.2 (1.0) | ||||

| Direct effects of tobacco | |||||||||||||

| Was the B&M satisfying? | 36.9 (4.3) | 43.5 (4.7) | 5.7 (2.0) | 20.9 (3.1) | 36.6 (3.7) | 2.6 (1.6) | 39.2 (4.9) | 28.0 (4.7) | 45.1 (5.5) | ||||

| Was the B&M pleasant? | 34.5 (4.2) | 41.7 (4.6) | 8.1 (2.6) | 20.4 (3.2) | 35.8 (3.6) | 0.5 (0.3) | 40.2 (5.1) | 28.5 (4.6) | 43.2 (5.4) | ||||

| Did the B&M taste good? | 35.4 (4.3) | 45.2 (4.8) | 16.2 (3.6) | 23.0 (3.3) | 41.5 (3.8) | 0.5 (0.2) | 45.6 (5.2) | 35.3 (5.3) | 47.7 (5.3) | ||||

| Did the B&M make you dizzy? | 13.0 (2.6) | 6.8 (2.5) | 2.8 (1.2) | 5.6 (1.5) | 9.4 (2.1) | 0.5 (0.2) | 10.8 (2.8) | 8.6 (3.0) | 10.2 (3.0) | ||||

| Did the B&M calm you down? | 27.9 (4.0) | 26.7 (4.1) | 5.3 (1.8) | 16.9 (2.8) | 23.0 (3.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 33.5 (4.7) | 19.1 (3.9) | 27.0 (4.8) | ||||

| Did the B&M help you concentrate? | 18.1 (3.5) | 16.4 (3.3) | 4.5 (1.7) | 10.7 (2.4) | 15.3 (2.5) | 0.5 (0.3) | 20.9 (4.3) | 13.7 (3.4) | 16.8 (3.7) | ||||

| Did the B&M make you feel more awake? | 16.0 (2.6) | 17.1 (2.9) | 4.3 (1.5) | 10.0 (1.9) | 15.2 (2.1) | 0.5 (0.3) | 18.9 (3.4) | 14.0 (2.8) | 16.4 (3.3) | ||||

| Did the B&M reduce your hunger for food? | 12.9 (2.5) | 8.9 (1.9) | 3.9 (1.2) | 8.0 (1.7) | 9.2 (1.5) | 0.5 (0.3) | 15.4 (3.1) | 10.3 (2.4) | 8.2 (1.8) | ||||

| Did the B&M make you sick? | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.7) | ||||

| Did the product taste like your own brand of B&M? | 34.9 (4.5) | 42.1 (4.6) | 14.2 (3.2) | 21.9 (3.3) | 38.9 (3.6) | 0.5 (0.3) | 43.3 (5.3) | 36.1 (5.2) | 41.8 (5.1) | ||||

| Did the product feel like your own brand of B&M? | 39.3 (4.6) | 42.6 (4.6) | 11.2 (2.8) | 22.4 (3.4) | 39.7 (3.6) | 0.5 (0.2) | 44.3 (5.3) | 36.5 (5.1) | 43.0 (5.2) | ||||

| Did the product feel as harsh as your own brand of B&M? | 27.2 (3.7) | 27.8 (3.8) | 4.0 (1.2) | 14.4 (2.5) | 24.9 (2.9) | 0.6 (0.3) | 28.3 (4.2) | 21.3 (3.8) | 28.5 (4.4) | ||||

| Did the product feel as mild as your own brand of B&M? | 30.2 (4.2) | 39.0 (4.5) | 6.5 (1.7) | 17.7 (2.9) | 32.7 (3.4) | 0.4 (0.2) | 35.1 (4.9) | 29.7 (4.7) | 35.8 (4.9) | ||||

| Would you like to smoke another B&M right now? | 23.0 (3.4) | 22.7 (3.7) | 28.4 (4.7) | 21.7 (3.1) | 27.8 (3.3) | 2.2 (1.7) | 41.1 (4.7) | 31.7 (4.9) | 23.8 (4.5) | ||||

| Smoking topography | |||||||||||||

| Number | 22.2 (1.9) | 22.2 (1.3) | 30.2 (0.1) | 25.5 (1.2) | 24.2 (1.2) | ||||||||

| Average volume (mL) | 53.6 (3.7) | 90.0 (8.9) | 98.7 (8.9) | 82.5 (6.4) | 79.1 (7.0) | ||||||||

| Total volume (mL) | 1106.7 (94.7) | 1901.5 (150.8) | 2972.6 (266.1) | 2093.9 (192.5) | 1893.3 (176.2) | ||||||||

| Duration (s) | 1.6 (0.1) | 2.1 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.1) | 1.9 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.1) | ||||||||

| Peak (mL/s) | 32.5 (1.9) | 46.1 (3.3) | 56.0 (3.5) | 45.4 (2.8) | 44.5 (2.8) | ||||||||

| Inter-puff-interval (s) | 34.7 (3.1) | 25.0 (2.0) | 57.9 (0.3) | 38.8 (2.7) | 39.5 (2.5) | ||||||||

| Amount product used (g) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.0) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) | |||||||||

B&M = Black&Mild; CO = carbon monoxide; SEM = standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis results for the DENS items were exluded due to the lack of significant main and interaction effects.

aTime levels: Plasma nicotine (baseline and 10, 20, 30min post-smoking); Heart rate (baseline and 5, 25min post smoking); CO levels and subjective items (pre- and post-smoking)

Plasma Nicotine

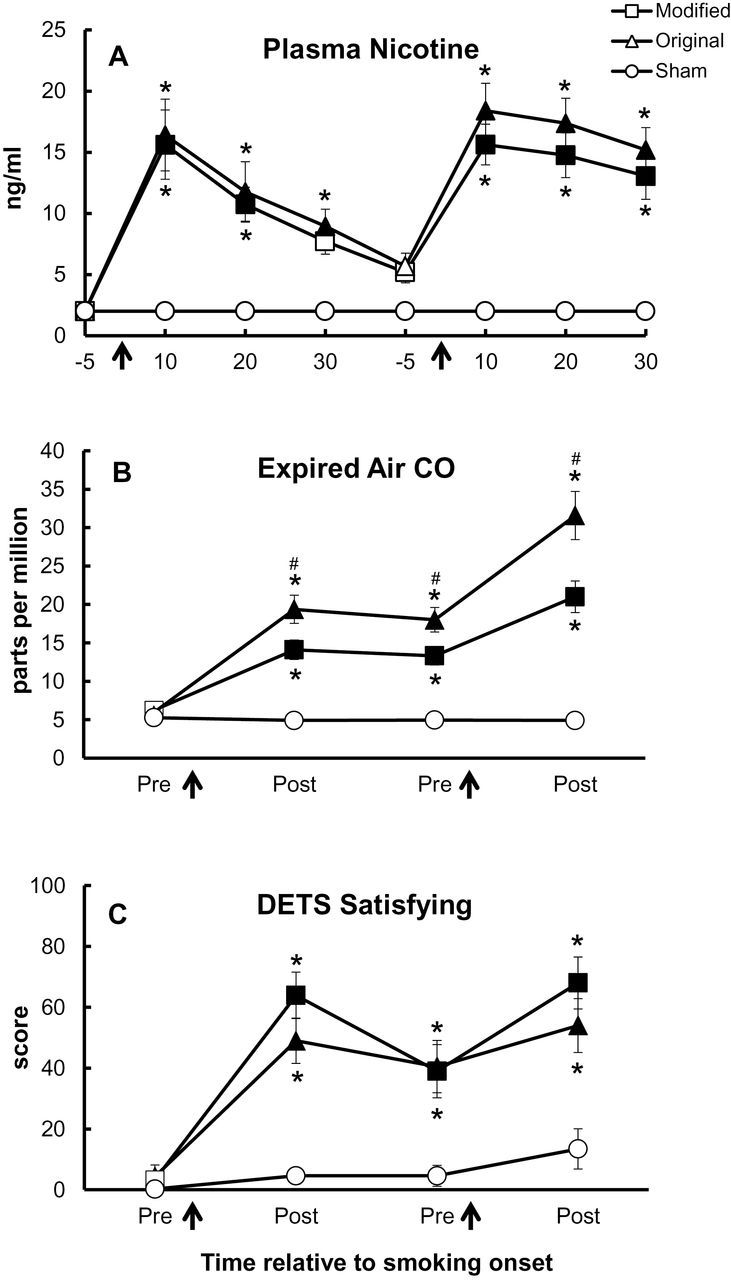

Significant interactions were observed for condition × bout, condition × time, and bout × time. Figure 1A demonstrates that mean (±SEM) plasma nicotine concentration for SHAM remained stable at 2.0±0.0ng/mL across all timepoints (ns). For original and modified B&M conditions, mean concentration increased significantly from pre- to post-smoking at each bout, with the largest increases occurring 10 minutes after the onset of smoking (Ps < .05). For modified B&M, mean plasma concentration increased from 2.0±0.0ng/mL at baseline to 15.6±2.8ng/mL at 10 minutes post-bout 1 onset, as well as from 5.2±0.9ng/mL at 5 minutes prior to bout 2 to 15.6±1.7ng/mL at 10 minutes post-bout 2 onset. A similar pattern was observed for original B&M: 2.0±0.0ng/mL at baseline, 16.4±2.9ng/mL at 10 minutes post-bout 1 onset, 5.7±1.1ng/mL at 5 minutes prior to bout 2, and 18.4±2.2ng/L at 10 minutes post-bout 2 onset (Ps < .05). Significant differences were observed between these two B&M conditions relative to SHAM at most timepoints, though no differences were observed between modified and original B&M at any timepoint (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Mean data (±1 SEM) for plasma nicotine (Panel A), expired air carbon monoxide (CO) (Panel B), and the Direct Effects of Tobacco Scale (DETS) item “Was the B&M satisfying?” (Panel C). Arrows indicate product administration, filled symbols indicate a significant difference from baseline within that condition, asterisks (*) indicate a significant difference from SHAM at that timepoint, and number signs (#) indicate a significant difference from modified Black&Mild smoking at that timepoint (Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference; P < .05).

Expired Air CO

For expired air CO, significant interactions were observed for condition × bout and condition × time (Figure 1B). Mean CO concentration for SHAM was 5.4±0.4 ppm at baseline and 4.9±0.4 ppm at the end of session (ns). Within original and modified B&M conditions, mean CO concentration increased significantly from baseline at all timepoints (all Ps < .05). For original B&M smoking, mean CO concentration was 6.2±0.5 ppm at baseline, 14.1±1.3 ppm post-bout 1, and 21.0±2.1 ppm at post-bout 2. For original B&M smoking, mean CO concentration was 5.6±0.6 ppm at baseline, 19.4±1.8 ppm at post-bout 1, and 31.6±3.1 ppm at post-bout 2. Additionally, mean CO concentration was significantly higher for original B&M than for modified B&M at all timepoints except baseline (Ps < .05).

Heart Rate

A significant condition × bout × time interaction was observed for heart rate. For the SHAM condition, average heart rate values remained stable across timepoints relative to baseline (67.0±1.3 bpm at baseline vs. 63.2±1.3 bpm at the end of session; ns). For the modified and original B&M conditions, heart rate increased significantly from pre- to post-smoking at each bout and the largest increases were observed immediately after the onset of smoking. For modified B&M, average values increased from 66.9±1.4 bpm at baseline to 76.9±2.0 bpm at 5 minutes post-bout 1 onset and 73.7±1.8 bpm at 5 minutes post-bout 2 onset (P < .05). For original B&M, average values increased from 67.7±1.6 bpm at baseline to 73.4±1.8 bpm at 5 minutes post-bout 1 onset and 74.6±1.5 at 5 minutes post-bout 2 onset (P < .05). While average heart rate for these two smoking conditions were significantly different from SHAM at all timepoints, heart rate did not differ between modified and original B&M conditions at any timepoint (ns).

Hughes–Hatsukami Withdrawal Scale

Modified and original B&M smoking, but not SHAM smoking, significantly decreased some withdrawal symptoms relative to baseline. Significant condition × time interactions were observed for the items “urges to smoke,” “craving,” and “anxious” (Fs > 3.4, Ps < .05). For the item “urges to smoke” (item with the largest F value for this interaction), average scores for SHAM remained high across session: 61.0±7.9 at pre-bout 1 to 57.8±9.3 at post-bout 2 (ns). Scores for modified and original B&M smoking were significantly decreased at both post-bout timepoints, as compared to baseline scores (Ps < .05). For instance, ratings for “urges to smoke” were decreased from 53.0±8.8 at baseline to 18.1±6.4 by the end of session for modified B&M, and from 46.9±9.2 to 18.3±6.1 for original B&M. These decreases for modified and original B&M were significantly lower than scores for SHAM at most timepoints (Ps < .05), though no significant differences were observed between modified and original B&M at any timepoint (ns). This same pattern of results was observed for the items “craving” and “anxious”.

Scores for “difficulty concentrating” (significant main effects of bout and time) generally decreased from baseline across timepoints for original and modified B&M, but not for SHAM. However, significant differences were only observed within the original B&M condition for baseline versus post-bouts 1 and 2 (Ps < .05). No other significant differences within or between conditions were observed (ns). A significant bout × time interaction was observed for the item “depression/feeling blue”. Scores were similar from pre- to post-smoking for bout 1 (8.5±2.8 vs. 8.1±2.6), and decreased from pre- to post-smoking for bout 2 (10.0±2.8 vs. 5.8±2.2; ns). The item “hunger” had a significant main effect of time in that scores increased from 26.5±4.4 at baseline to 35.7±4.7 by the end of session (ns across timepoints).

Tiffany–Drobes Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Brief

Factor 1 (“intention to smoke”) and Factor 2 (“anticipation of relief from withdrawal”) subscales were significant for condition × bout (Fs > 7.5, Ps < .01) and condition × time (Fs > 7.9, Ps < .01) interactions. Factor 1 scores for SHAM did not change across timepoints, but decreased significantly from pre- to post-smoking at each bout for modified and original B&M smoking. Scores for modified B&M were 18.2±2.2 for pre-bout 1, 13.2±2.2 for post-bout 1, 14.1±2.3 for pre-bout 2, and 8.8±2.3 for post-bout 2 (P < .05). Scores for original B&M were 19.9±2.3 for pre-bout 1, 10.3±2.1 for post-bout 1, 12.2±2.2 for pre-bout 2, and 7.1±1.4 for post-bout 2. Scores did not differ significantly between modified and original B&M conditions (ns). A similar pattern was observed for Factor 2 scores, though post-hoc tests revealed that these differences within and across conditions were less reliable.

Direct Effects of Tobacco Scale

Most Direct Effects of Tobacco Scale items were significant for a condition × bout × time interaction (Fs > 3.3, Ps < .05), as shown in Table 1. The majority of these items (“satisfying,” “pleasant,” “taste good,” “harsh as OB,” “mild as OB,” “feel like OB,” “calm you down,” and “help you concentrate”) revealed a similar pattern of results in that scores for original and modified B&M products were significantly increased relative to SHAM; however, few differences were observed between the B&M smoking conditions. For the item “Was the B&M satisfying?” (Figure 1C; the item with the largest F value), scores were significantly increased from baseline to post-smoking at both bouts for the modified and original B&M conditions (Ps < .05 at all timepoints within each condition). For modified B&M, scores increased significantly from 3.3±2.7 to 63.9±7.6 for pre- to post-bout 1, and also from 39.0±8.8 to 68.0±8.5 for pre- to post-bout 2 (Ps < .05). For original B&M, scores were 4.3±3.8, 49.0±7.5, 40.5±8.6, 54.0±8.9 for pre- and post-bouts 1 and 2, respectively (Ps < .05 for all timepoints relative to pre-bout 1). These ratings for modified and original B&M were significantly higher than those for SHAM (Ps < .05 between conditions), with the highest rating for SHAM occurring after the second bout (13.4±6.6; ns across all SHAM timepoints). However, scores did not differ between modified and original B&M at any timepoint (ns). Other Direct Effects of Tobacco Scale items (eg, “dizzy”, “awake”) revealed a similar pattern (increased ratings from pre- to post-bouts, increased ratings for original and modified B&M relative to SHAM), though the results were less reliable (very few significant differences within or between conditions).

Direct Effects of Nicotine Scale

No main or interaction effects were observed for any of the Direct Effects of Nicotine Scale items (all Fs < 4.4, Ps > .05).

Smoking Topography

All topography outcomes were significant for a main effect of condition (Fs > 3.9, Ps < .05). No main effects of bout, or condition × bout interactions, were observed for any topography outcomes (Fs < 2.5, Ps > .05). Collapsed across bouts, no significant differences were observed between any conditions for average puff number or duration (Ps > .05). Additionally, no significant differences were observed between modified and original B&M smoking for average and total puff volume, as well as IPI (Ps > .05). However, average puff volumes for original B&M smoking (53.6±3.7mL) were significantly lower than those for SHAM (98.7±8.9mL; P < .05). For IPI, values were significantly lower for modified (25.0±2.0 seconds) and original (34.7±3.1 seconds) B&M relative to SHAM (57.9±0.3 seconds; Ps < .05). Average peak flow was significantly lower for original B&M (32.5±1.9mL/s), relative to modified B&M (46.1±3.3mL/s) and SHAM (56.0±3.5mL/s; P < .05).

Amount Smoked

No main or interaction effects (Fs > 3.1, Ps < .05) were observed for the amount of tobacco smoked in the modified or original conditions.

Discussion

Users of B&M cigarillos may engage in the practice of “hyping,” or removing the inner tobacco binder before smoking, for reasons that include the reduction of smoking-related health risks. An analysis of YouTube videos depicting the practice of B&M modification supports this idea, as many users recommended removal of the “cancer paper” prior to smoking.16 Results reported here and elsewhere17 demonstrate that B&M smokers are exposed to less CO, but similar levels of nicotine, when they remove this inner binder. This reduction in CO exposure cannot be explained by differences in smoking topography, however. Average peak flow was the only topography outcome that revealed significant differences between these smoking conditions; values were lower for original than for modified B&M across bouts (mean difference = 13.6±3.1mL/s; P < .05). Still, whether this decreased level of CO exposure results in clinical meaningful outcomes remains unknown.

Of course, the modification process naturally changes the nature of a B&M cigarillo. Perhaps the constituents of the removed reconstituted tobacco binder generate more CO than the remaining components, the loose tobacco filler wrapped in a leaf lamina. Additionally, the binder from an original B&M cigarillo may inhibit airflow that would normally dilute the smoke with each puff. Also notable is that less product is available for consumption, and thus CO production, when modified. The average pre-smoking weight of modified versus original B&M cigarillos was 2.1±0.05 grams versus 3.0±0.04 grams, respectively (collapsed across bouts). These differences in weight may be due not only to the removal of the binder, but also the loss of some filler during the modification process. Notable is that these product changes are touted by users as a way to change the burn rate of cigarillos, and making them smoother for puffing,16 despite the fact that study results do not support this idea. That is, neither smokers’ topography nor their amount of product used differed as a function of product modification.

Product modification also did not alter participants’ subjective experience. Very few significant differences were shown between modified and original B&M smoking on subjective measures of product acceptability and nicotine/tobacco withdrawal symptomatology. Still, both smoking conditions increased positive ratings of drug effects (pleasant, satisfying, tastes good) and decreased the magnitude of withdrawal symptoms (craving, anxiousness) following overnight abstinence. Our previous work20 showed that smoking original B&M cigarillos produces a variety of pleasant product-related effects, though does not suppress withdrawal symptoms reliably. These contrasting findings may be due to participants’ differing levels of nicotine/tobacco dependence. Participants’ average number of B&M cigarillos per day was 1.9 (SD = 2.5; median = 0.9) in our previous work,20 compared to 2.6 (SD = 2.1; median = 2.0) for those in our current study. Also notable is that, in our previous work, the effects of B&M cigarillos were assessed using a standardized puffing procedure: 10 puffs with 30-second IPIs. Mean peak plasma concentration for this puffing regimen was 6.5±1.1ng/mL, while that for the ad libitum smoking of original cigarillos in this study was 22.5±2.9ng/mL. Consequently, the average plasma nicotine levels reported here—11.8±0.7ng/mL for modified and 13.4±0.9ng/mL for original—approach those for ad libitum cigarette smoking (collapsed across bouts = 12.9±0.6ng/mL21). Importantly, results add to the growing literature17,20 that B&M smoking exposes users to pharmacologically active doses of nicotine, as well as relatively high levels of CO. B&M users are clearly inhaling the smoke when they puff on these products. Specifically, these levels of nicotine in plasma immediately after smoking are indicative of lung, rather than buccal, absorption.28

Study results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Participants were not blinded to study conditions, possibly affecting their response to the products administered. We requested that participants “hype” their own B&M cigarillos to demonstrate that they were skilled at performing this behavior and to simulate their natural smoking experience. Participants were largely non-Hispanic black males (n = 18 out of 20), and thus results may not generalize to smokers of other racial/ethnic groups or to females. However, most available surveys suggest that cigar use is more prevalent among males than females,3,29,30 as well as among non-Hispanic blacks.31,32 The demographics of B&M smokers who engage in hyping have not been examined systematically, though existing work suggests that it is a popular practice among black males.13,15,16

Another limitation may include the questionnaire items, or lack thereof, used to assess subjective outcomes. Cigarillo smokers claim that their impetus for hyping is, in part, to enhance the product flavor and “smoothness” for puffing. This sample of “hypers” did not reveal many significant differences in subjective ratings despite the fact that they were not blinded to study condition. Perhaps the subjective items used in this study (eg, “Does the product taste good?”, “Was the product satisfying?”) were not sensitive enough to capture these specific effects. Also notable is that our sample of cigarillo “hypers” ranged in age from 19 to 32 years. The smoking of cigarillos is a popular practice among younger age groups, and a portion of these groups may be engaging in “hyping”. Unfortunately, the extant literature describing this practice among youth include only testimonials15 and YouTube video observations (ie, age of “hypers” unable to be verified).16

Combined with previous work—qualitative interviews,13,15 content analysis of social media,16 and clinical laboratory methods17—our results help clarify the relationship between reasons for and effects of “hyping” a B&M cigarillo. Unorthodox tobacco use behavior is an important area for future study, particularly in light of impending Food and Drug Administration regulatory action for cigar products.33 More work is needed on the pervasiveness of this practice, the impact of users’ beliefs on behavior, and the impact on toxicant exposure.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R21CA161317, as well as the National Institute on Drug Abuse under Award Number P50DA036105 and the Center for Tobacco Products of the US Food and Drug Administration. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Kilgalen and Janet Austin for their diligent efforts on data collection and management, as well as Dustin Long for help with statistical analyses during the review process.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011 and 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(45):893–897. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6245a2.htm. Accessed August 12, 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 national survey on drug use and health: detailed tables 2013. www.gjmboard.org/index.php/results-from-the-2012-national-survey-on-drug-use-and-health-summary-of-national-findings-and-detailed-tables/ Accessed November 8, 2014.

- 3. Nasim A, Blank MD, Cobb CO, Eissenberg T. Patterns of alternative tobacco use among adolescent cigarette smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(1–2):26–33. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Prev Med. 2014;62:14–19. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saunders C, Geletko K. Adolescent cigarette smokers’ and non-cigarette smokers’ use of alternative tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(8):977–985. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigars: Fact sheet 2007. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/tobacco_industry/cigars/ Accessed November 29, 2014.

- 7. Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. State excise tax rates for non-cigarette tobacco products 2014. www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0169.pdf Accessed November 29, 2014.

- 8. Villanti AC, Richardson A, Vallone DM, Rath JM. Flavored tobacco product use among U.S. young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):388–391. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown JE, Luo W, Isabelle LM, Pankow JF. Candy flavorings in tobacco. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2250–2252. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1403015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Foulds J, Steinberg MB. Cigar use before and after a cigarette excise tax increase in New Jersey. Addict Behav. 2004;29(9):1799–1807. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soldz S, Dorsey E. Youth attitudes and beliefs toward alternative tobacco products: cigars, bidis, and kreteks. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32(4):549–566. doi:10.1177/1090198105276219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wray RJ, Jupka K, Berman S, Zellin S, Vijaykumar S. Young adults’ perceptions about established and emerging tobacco products: results from eight focus groups. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(2):184–190. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jolly DH. Exploring the use of little cigars by students at a historically black university. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(3):A82 www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/jul/07_0157.htm. Accessed March 24, 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malone RE, Yerger V, Pearson C. Cigar risk perceptions in focus groups of urban African American youth. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(4):549–561. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Page JB, Evans S. Cigars, cigarillos, and youth: emergent patterns in subcultural complexes. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2003;2(4):63–76. doi:10.1300/J233v02n04_04. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nasim A, Blank MD, Cobb CO, Berry BM, Kennedy MG, Eissenberg T. How to freak a Black & Mild: a multi-study analysis of YouTube videos illustrating cigar product modification. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(1):41–57. doi:10.1093/her/cyt102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fabian LA, Canlas LL, Potts J, Pickworth WB. Ad lib smoking of Black & Mild cigarillos and cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(3):368–371. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Breland AB, Kleykamp BA, Eissenberg T. Clinical laboratory evaluation of potential reduced exposure products for smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(6):727–738. doi:10.1080/14622200600789585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Ambrose BK, Corey CG, Conway KP. Preference for flavoured cigar brands among youth, young adults and adults in the USA [published online ahead of print April 10, 2014]. Tob Control. 2014. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013–051408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blank MD, Nasim A, Hart A, Jr, Eissenberg T. Acute effects of cigarillo smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(9):874–879. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cobb CO, Weaver MF, Eissenberg T. Evaluating the acute effects of oral, non-combustible potential reduced exposure products marketed to smokers. Tob Control. 2010;19(5):367–373. doi:10.1136/tc.2008.028993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43(3):289–294. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3(1):7–16. doi:10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Foulds J, Stapleton J, Feyerabend C, Vesey C, Jarvis M, Russell MA. Effect of transdermal nicotine patches on cigarette smoking: a double blind crossover study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1992;106(3):421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Evans SE, Blank M, Sams C, Weaver MF, Eissenberg T. Transdermal nicotine-induced tobacco abstinence symptom suppression: nicotine dose and smokers’ gender. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14(2):121–135. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huynh H, Feldt LS. Estimation of the box correction for degrees of freedom from sample data in randomized block and split-plot designs. J Educ Behav Stat. 1976;1(1):69–82. doi:10.3102/10769986001001069. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Keppel G. Design and Analysis: A Researcher’s Handbook. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benowitz NL, Porchet H, Sheiner L, Jacob P., III Nicotine absorption and cardiovascular effects with smokeless tobacco use: comparison with cigarettes and nicotine gum. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988;44(1):23–28. doi:10.1038/clpt.1988.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Backinger CL, Fagan P, O’Connell ME, et al. Use of other tobacco products among U.S. adult cigarette smokers: prevalence, trends and correlates. Addict Behav. 2008;33(3):472–489. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bombard JM, Rock VJ, Pederson LL, Asman KJ. Monitoring polytobacco use among adolescents: do cigarette smokers use other forms of tobacco? Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(11):1581–1589. doi:10.1080/14622200802412887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2012–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):542–547. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm632 5a3.htm. Accessed September 20, 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Messer K, White MM, Strong DR, et al. Trends in use of little cigars or cigarillos and cigarettes among U.S. smokers, 2002–2011 [published online ahead of print September 19, 2014]. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Food and Drug Administration. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the federal food, drug, and cosmetic act, as amended by the family smoking prevention and tobacco control act; regulations on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products 2014. www.federalregister.gov/articles/2014/04/25/2014–09491/deeming-tobacco-products-to-be-subject-to-the-federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act-as-amended-by-the Accessed November 29, 2014.