Abstract

The main purpose of the current investigation was to determine whether the Vocal Development Landmarks Interview—Experimental Version (VDLI-E) was sensitive to variation in the vocal development of infants and toddlers who are hard of hearing. The VDLI-E is an interactive parent interview that uses audio samples of authentic infant vocalizations to make targeted vocal behaviors clear and understandable to parents without the need for technical terms, verbal descriptions, or adult modeling of infant productions. The VDLI-E was found to be sensitive to age and hearing and was related to performance on concurrent measures of early auditory skills, expressive vocabulary, and overall expressive language abilities. These findings provide preliminary support for the utility of this measure in monitoring the impact of early auditory experiences on vocal development for 6- to 18-month-old children who are hard of hearing.

Auditory experience and feedback are critically important in the development of the ability to coordinate phonation and articulation. This ability is essential for the production of the early speech sounds that serve as the foundation for developing spoken language (Koopmans-van Beinum, Clement, & van den Dikkenberg-Pot, 2001). Hearing loss during infancy restricts access to auditory input and feedback, which has historically resulted in delays in the development of early speech-like sounds for these infants (Moeller et al., 2007a; Oller & Eilers, 1988; von Hapsburg & Davis, 2006). Such delays in reaching early vocal development milestones are associated with subsequent delays in spoken language development. However, for children with hearing loss, universal newborn hearing screening programs have opened the door for early provision of well-fit hearing assistance devices (e.g., hearing aids and cochlear implants) and enrollment in early intervention within the first year of life. These early interventions should serve to optimize auditory access and development when spoken language is the goal. To determine whether these interventions are successful in doing so, there is a need for sensitive measures of early development (Eisenberg et al., 2007), including those that monitor expected changes related to auditory experience and feedback.

Given the known contributions of auditory abilities to vocal development, one method for gaining insight into children’s auditory development is to examine their early vocalizations (Kishon-Rabin, Taitelbaum-Swead, Ezrati-Vinacour, & Hildesheimer, 2005; Kishon-Rabin, Taitlebaum-Swead, & Segal, 2009; Oller & Eilers, 1988; von Hapsburg & Davis, 2006). The examination of early vocal development for infants with hearing loss has both theoretical and clinical implications. Theoretically, such investigations may shed light on the role of auditory experience in early vocal development. Clinically, the ability to assess the early vocal development of infants with hearing loss may provide intervention teams with a means of monitoring the effectiveness of amplification and intervention strategies (Moeller, Bass-Ringdahl, Ambrose, VanDam, & Tomblin, 2011). However, traditional assessments of early vocal behavior have often relied on collecting recordings of vocalizations in laboratory settings, which are then analyzed through labor intensive transcriptions or scoring. These procedures require extensive training and commitment of substantial time and financial resources (Eilers & Oller, 1994; Iyer & Oller, 2008; Stark, 1983; von Hapsburg & Davis, 2006). Additionally, these measures lack ecological validity, as infants may not vocalize in the same manner during a short session in a laboratory setting as they would throughout the day in their natural environments. More recently developed tools have turned toward parent report to assess the early vocal development of infants (Cantle-Moore, 2004; Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005). Although these tools have proved helpful, reliance on verbal description and adult modeling of targeted infant vocal behaviors may fall short of providing parents with the information they need to accurately distinguish among specific vocal behaviors and report on the types of vocalizations their child is producing.

In an effort to address the potential limitations of existing strategies for assessing children’s early vocalizations through parent report, the Vocal Development Landmarks Interview—Experimental Version (VDLI-E) was developed. The VDLI-E is an interactive parent interview that uses audio samples of authentic infant vocalizations to make vocal behaviors clear and understandable to parents without the need of technical terms, verbal descriptions, or adult modeling of infant productions. The main purpose of the current investigation was to determine whether the VDLI-E is sensitive to variation in the vocal development of infants and toddlers with hearing loss.

Early Vocal Development of Infants With Typical Hearing

The development of prelexical and early lexical behavior is an essential component of human development. Infants’ prelinguistic vocalizations serve as an index of auditory abilities (Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005, 2009) and a precursor to speech and language development (Oller, Eilers, Neal, & Schwartz, 1999; Stark, 1980). As with the development of gross motor skills, prelexical and early lexical development in infants with typical hearing (TH) tends to follow a continuum of predictable yet distinct phases (Nathani, Ertmer, & Stark, 2006; Oller et al., 1999; Stoel-Gammon, 2011). When they are first born, infants can only produce vegetative and reflexive sounds (e.g., burps, coughs, cries, squeals) that are mostly physiological in nature. As infants begin to develop, they start to gain control over their motor and speech movements and thus, control of their vocalizations (Stoel-Gammon, 2011). This process happens quite slowly, beginning around 3 months of age, with explorations of the vocal tract and the production of vowel-like sounds, followed by more refined and controlled vocal behaviors. Between 3 and 8 months of age, infants begin to produce a variety of vocalizations, usually consisting of vowels, vowel glides, growls, ingressives (e.g., sounds produced on inhalation), and high-pitch squeals (Nathani et al., 2006). Children also begin primitive attempts at combining consonant-like and vowel-like sounds, known as marginal babbling, around this time (Oller, 2000). Sometime between the ages of 5 and 10 months, infants begin to coordinate the behaviors of multiple systems, including the neurophysiological-motor, tactile, perceptual, and auditory systems (von Hapsburg & Davis, 2006). During this time infants begin to produce canonical syllables. These are differentiated from marginal syllables by the quick production of the vowel and consonant without any breaks in phonation or drawn out transitions (Oller, 2000). Infants at this stage also tend to produce both reduplicated [bababa] and variegated [bagugee] strings of syllables (Ertmer & Iyer, 2010). The final stage of prelinguistic vocal development is reached by infants sometime after 9 months of age and tends to just precede the onset of formal word production (Ertmer & Iyer, 2010). Vocalizations produced at this stage include complex combinations of phonemes, such as those ending with a consonant, and strings of variegated syllables that sound speech-like in timing and intonation, but are unintelligible (i.e., jargon). Overall, children’s vocal productions at this stage are becoming more sophisticated and word-like, laying the framework for the single word stage of development that includes a mix of prelinguistic vocalizations and words (Robb, Bauer, & Tyler, 1994). First words typically emerge between 10 and 13 months, although some typically developing children may not use first words until closer to 16 months (Bates, Bretherton, & Snyder, 1991). Two-word combinations typically emerge after a child has a vocabulary of at least 50 words, which may occur around 18 months of age (Bates, Dale, & Thal, 1995; Nelson, 1973).

Early Vocal Development of Infants With Hearing Loss

For children with hearing loss, the predictable pattern of vocal development that occurs for infants with TH may be disrupted or delayed due to limitations in accessing auditory information (Eilers & Oller, 1994; Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005, 2009). For example, infants with hearing loss have been found to have delays in the onset of canonical babbling relative to their hearing peers, although the delays are found less consistently for children who are hard of hearing (HH) as opposed to deaf (Eilers & Oller, 1994; Moeller et al., 2007a; Nathani & Oller, 2007; von Hapsburg & Davis, 2006). Additionally, after the onset of canonical babbling, the sounds used in babble differ from those used by peers with TH, with children with hearing loss having more restricted consonant and vowel inventories (Moeller et al., 2007a; Stark, 1983; Stoel-Gammon & Otomo, 1986; Stoel-Gammon, 1988; von Hapsburg & Davis, 2006). Among other differences, the consonant inventories of children with hearing loss were noted to have more labial consonants and fewer alveolar consonants than those of TH peers. Differences have also been noted in the rate of progression toward using more complex syllable shapes (Moeller et al., 2007a). These differences are maintained as children progress to the first word stage, a transition that is also often delayed in children with hearing loss (Moeller et al., 2007b). Although the majority of these studies included children with a wide range of hearing losses, the groups were weighted toward inclusion of infants with severe and profound losses, including a small number who used cochlear implants. Consequently, it is unclear to what extent findings apply to children with mild-to-severe hearing losses.

Further evidence that these delays and differences in early vocal development are attributable to the limited auditory access experienced by infants with hearing loss can be found in research documenting changes in vocal development that occur following cochlear implantation. That is, when provided with auditory access via a cochlear implant, the speech development trajectories of young children who are deaf have been shown to change dramatically. Ertmer and Jung (2012) followed a group of 13 children implanted between 8 and 35 months of age and 11 peers with TH who were matched for hearing age. They found that the children with cochlear implants demonstrated relatively rapid progress in early vocal development. For example, at the end of 1 year with hearing, less than 40% of the vocalizations of the cochlear implant group were at the precanonical level, as compared to 80% of those of the TH group. Similarly, the cochlear implant group needed fewer months with hearing than the TH group to achieve the benchmark of 20% of vocalizations being canonical. Ertmer and Jung’s finding that vocal development occurs with relative rapidity after receipt of a cochlear implant is in agreement with findings of other studies (Ertmer, Strong, & Sadagopan, 2003; Ertmer, Young, & Nathani, 2007; Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005; Moore & Bass-Ringdahl, 2002; Schauwers, Gillis, Daemers, De Beukelaer, & Govaerts, 2004).

Although there are numerous studies exploring the vocal development of children following the receipt of a cochlear implant, there is less research focused on early vocal development of children who are HH and who use hearing aids. Exploration of the early vocal and speech development of this group could shed light on the effects of limited, but not absent, access to auditory input, and how increased access via hearing aids influences the rate at which early vocal milestones are achieved. Additionally, an ecologically valid means of assessing and monitoring the quality and quantity of early vocalizations in infants with hearing loss could provide clinicians and practitioners with an indirect measure of these infants’ developing auditory abilities in response to the provision of amplification (Eilers & Oller, 1994; Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005, 2009). Such information would be extremely valuable when planning and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions for these children.

Measures of Early Vocal Development

Parents are in a unique position to provide valuable insight into the auditory and linguistic capabilities of their children. Studies that examine early vocal development of infants often employ the use of parent report due to the limited cooperation and linguistic capabilities of infants (Ben-Itzhak, Greenstein, & Kishon-Rabin, 2014). Another reason parent report is often used is the unique ability parents have to recognize subtle changes in their children’s development (Oller, Eilers, & Basinger, 2001). Furthermore, unlike direct testing, which tends to be expensive, time consuming, and lacks strong ecological validity (Lichtenstein, 1984; Rescorla & Alley, 2001), parent report tends to have high ecological validity and is relatively inexpensive. Parent report has also been shown to yield valid and reliable estimates of children’s early vocal behaviors (Dale, 1991; Moeller et al., 2011; Oller et al., 2001).

Currently, only a limited number of clinical measures exist that are appropriate for assessing the early vocal development of infants and toddlers (Kishon-Rabin et al., 2009). One such measure, the Production Infant Scale Evaluation (PRISE; Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005, 2009), is an 11-item parent-report questionnaire that evaluates the quality and frequency of prelexical vocalizations of infants. Another measure, the Infant Monitor of Vocal Production (IMP; Cantle-Moore, 2004), is a 16-item criterion-referenced parent-report scale that evaluates changes in the early vocal development of infants with hearing loss during the first year after they receive a cochlear implant or hearing aids. The PRISE and the IMP emerged out of the need for efficient, sensitive, and developmentally accurate measures that could help guide intervention efforts of clinicians and practitioners. Unlike measures of vocal development that require the clinician to elicit child vocalizations, the PRISE and the IMP are both measurement tools that rely on parent-report of child vocal behaviors and can be easily administered in the comfort of a parent’s home.

Early reports on these two measures provide promising results regarding the potential for use with young children with hearing loss. In a validation study, several findings indicated that the PRISE scores were sensitive to children’s auditory abilities: (a) a strong positive relationship between scores on the PRISE and scores on a measure of early auditory development for children with TH, (b) a negative relationship between scores on the PRISE and degree of hearing loss for children with mild to profound hearing loss, and (c) the ability of the PRISE to identify infants with unilateral hearing loss who were delayed in speech development per the results of a formal communication assessment (Kishon-Rabin et al., 2009). A similar pilot study was recently conducted with the IMP. Cantle Moore (2014) used the measure to track the vocal development of 18 infants with hearing loss after fitting of devices and nine infants with TH during the first year of life. Findings indicated that the IMP was sensitive to changes in vocal development for both groups and that the developmental trajectories of the two groups mirrored one another.

However, there are obvious limitations to parent report. Situations that require parents to report on behaviors that are rarely observed may result in poor reliability. Research has revealed that the most reliable behaviors reported on by parents include current, observable behaviors that do not involve much inference or interpretation (Lichtenstein, 1984). Parent report that is based on verbal description of unfamiliar terms and behaviors may also affect the reliability of parent report (Moeller et al., 2011). This particular limitation may apply to both the PRISE and IMP, which are both dependent on the verbal description of targeted vocal behaviors. Some of the words used in these measures are technical and may not be broadly understood by caregivers. For example, one of the items on the PRISE asks “Does the infant reduplicate syllables? For example: when the infant is in the crib or playing alone or with one of the family members, does he produce sounds such as mamama, bababa, etc., or sounds such as: babi, gadu?” Although the authors of the PRISE and IMP make a concerted effort to provide clear and accurate descriptions of targeted vocal behaviors, such descriptions may fall short of providing parents with the information they need to accurately distinguish whether their child is producing the targeted vocal behaviors. Furthermore, these measures assume that administration is being carried out by individuals who have a thorough understanding of early vocal development. However, the typical early interventionist may not possess such expertise, which could lead to administration issues with these scales. The VDLI-E was specifically designed to overcome these limitations by providing parents with audio examples of authentic infant vocalizations that are often presented in contrasting pairs to ensure full understanding of the characteristics of vocal behaviors being queried. Such an approach is designed to allow the examiner to support parental understanding of the targeted vocal behaviors and reduce the ambiguity of the information being sought (Moeller et al., 2011).

The Vocal Development Landmarks Interview—Experimental Version (VDLI-E)

The VDLI-E was originally developed for use with 6- to 21-month-old children in the Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss (OCHL) project, a 5-year longitudinal study which measured a broad range of child and family outcomes in a group of children with mild-to-severe hearing loss (Moeller et al., 2011). The VDLI-E queries parents regarding children’s use of 17 early vocal behaviors. To overcome the perceived limitations of other parent-report measures of early vocal development, the VDLI-E utilizes two innovative techniques: providing audio samples of authentic infant vocalizations of targeted VDLI-E items and, for similar vocal behaviors, providing contrasting audio samples. The interview is presented with the aid of a PowerPoint presentation, which allows for playing the audio samples. The audio samples are each paired with colorful images of children for visual interest. Parents are told prior to viewing the first slide that the pictures are only provided for interest and do not suggest that a child of a certain age produced the sounds. See Figure 1 for an example of a slide from the VDLI-E PowerPoint presentation. This slide presents one of the contrasting audio samples. In this example, to determine whether children are producing reduplicated and/or variegated babble sequences, the examiner says “Notice that the little ones on the top row repeat the same sound in a sequence.” The examiner pauses to play three examples of infants producing reduplicated babble sequences. The examiner then says “The children on the bottom row are mixing up the consonants. They use more than one.” The examiner then plays two examples of variegated babble sequences. After the parent reports on which vocalization type is most common for his or her child, the examiner queries how frequently the parent hears the child produce the vocalization on a typical day (never, rarely, sometimes, frequently/a lot) and records the answers. This contrast technique is also used for other behaviors that could easily be confused, for example, to highlight how marginal syllables differ from true canonical syllables, how variegated canonical sequences contrast with jargon-like utterances, and how the production of ingressive and egressive vocalizations differ.

Figure 1.

Slide used when querying parents regarding reduplicated and variegated babble sequences.

Research Questions

The current work addresses four research questions that serve to support the goal of determining whether the VDLI-E is sensitive to variation in the vocal development of infants and toddlers with hearing loss:

- Is the VDLI-E sensitive to development of prelexical and early lexical vocal behaviors of infants who are HH at 6, 12, and 18 months of age?It was predicted that the VDLI-E total score and subscale scores would be sensitive to age using both cross-sectional and longitudinal data.

- Does severity of hearing loss relate to outcomes on the VDLI-E?It was predicted that severity of hearing loss would be negatively related to VDLI-E total scores.

- Is the VDLI-E sensitive to differences in early vocal development between groups of 18-month-old infants who have TH and who are HH?It was predicted that the TH group would outperform the HH group on the VDLI-E total score and word score. However, differences were predicted to be less pronounced on the two scales representing earlier development (precanonical and canonical), as most children were predicted to be at the word stage by 18-months of age.

- How do VDLI-E scores relate to scores on concurrent measures of auditory development and expressive language for HH 12 and 18 month olds?It was predicted that the VDLI-E total scores would be strongly correlated with scores on concurrent measures of early communication abilities.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 80 children with mild-to-severe hearing loss and a group of 21 children with TH who were matched for socioeconomic status (as represented by maternal education). All children were participants in the aforementioned OCHL study. Recruitment was completed by research teams at Boys Town National Research Hospital, the University of Iowa, and the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, as described in Tomblin et al. (2015). For HH children in the OCHL study, inclusion criteria at the time of recruitment were (a) chronological age between 6 months and 7 years, (b) better-ear pure tone average (BEPTA) between 25 and 75 dB HL, (c) no cochlear implant, (d) reside in a home where English was the primary language, and (e) no significant cognitive or motor delays. The latter two criteria also applied to children with TH in the OCHL study, along with the additional criterion of a four-frequency PTA ≤20 dB HL in both ears. See Table 1 for additional demographic information on the participants, broken down by subgroups as described in a forthcoming section.

Table 1.

Demographic and audiologic characteristics for the participants for subgroups of participants

| Characteristic | HH–cross-sectional (n = 80) | HH-longitudinal (n = 16) | HH-18 month (n = 74) | TH-18 month (n = 21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal education | ||||

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| High school or less | 13 (16.3%) | 1 (6.3%) | 12 (16.2%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| Some college | 25 (31.2%) | 3 (18.8%) | 23 (31.1%) | 4 (19.0%) |

| College graduate | 29 (23.8%) | 4 (25.0%) | 18 (24.3%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| Graduate education | 23 (28.7%) | 8 (50%) | 21 (28.4%) | 7 (33.3%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 47 (58.7%) | 7 (43.8%) | 41 (55.4%) | 11 (52.4%) |

| Female | 33 (41.3%) | 9 (56.3%) | 33 (44.6%) | 10 (47.6%) |

| Age HA fitting (months) | ||||

| Mean | 5.10 | 3.77 | 5.15 | NA |

| SD | 3.34 | 1.56 | 3.44 | NA |

| Range | 1–17 | 1–7 | 1–17 | NA |

| BEPTAa | ||||

| Mean | 49.63 | 49.22 | 49.82 | NA |

| SD | 12.57 | 15.95 | 12.81 | NA |

| Range | 16.25–77.50 | 25.00–77.50 | 16.25–77.50 | NA |

| BESIIb | ||||

| Mean | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.76 | NA |

| SD | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.16 | NA |

| Range | 0.19–0.96 | 0.40–0.93 | 0.19–0.96 | NA |

Note. HH, hard of hearing; TH, typical hearing; HA, hearing aid; BEPTA, better-ear pure tone average; BESII, better-ear Speech Intelligibility Index.

aAlthough eligibility criteria for HH children included a BEPTA no better than 25 dB HL, exceptions to this criterion were made to allow for inclusion of children with bilateral, high-frequency hearing loss. Additionally, children with BEPTAs that progressed beyond 75 dB HL during the course of the study were retained in the study unless they received a cochlear implant.

bBESII was unavailable for seven children, two of whom were in the HH-longitudinal group and four of whom were in the HH-18 month group.

Procedures

Upon enrollment in the OCHL study, parents provided information regarding the child’s audiologic history (e.g., age at which HH children were fit with hearing aids) and family background (e.g., maternal education). After enrollment, children participated in scheduled assessments tied to the child’s age, as described in Tomblin et al. (2015). The OCHL assessment visits of relevance to the present work occurred within a 3 month window of when children were 6, 12, and 18 months of age. Thus, while some participants completed all three visits, other participants completed only the 12 and 18 month visits, or only the 18 month visit. Few TH children were enrolled prior to 18 months of age, thus the TH group only includes children contributing VDLI-E data at 18-months. Each visit included administration of the VDLI-E and, for HH children, an audiologic assessment. Additionally, at the 12-month visit, parents completed questionnaires describing their child’s auditory skills and expressive vocabulary and children were engaged in a clinician-elicited measure of overall expressive language abilities. At the 18-month visit, parents completed questionnaires describing their child’s auditory skills, expressive vocabulary, and overall expressive language abilities. Each of these measures is described below.

Administration of the VDLI-E

The VDLI-E was administered by a research assistant in a face-to-face setting with the parent. A laptop was utilized to display the PowerPoint presentation and play the audio samples. Parents were presented with open-ended warm up questions before being asked the questions that contributed to scoring for the measure. The first open-ended question was “What sounds does your child make on a typical day”? This allowed the examiner to make an early determination of whether the child appeared to be at the precanonical, canonical, or word stage. Before proceeding to the items targeting specific vocal behaviors, parents were instructed that for each item they should think about their child on a typical day and determine whether their child produced any vocalizations like the ones that would be played. Parents were told that they would be asked whether their child makes sounds like any of the audio samples and, if so, how often. Parents were then presented with a scale showing four frequency options (never, rarely, sometimes, frequently/a lot) and told they could look at the scale each time when making a determination of how often their child sounded like the set of audio samples.

Fifteen slides containing audio examples were used to query parents about the 17 vocal behaviors targeted on the VDLI-E. The VDLI-E is divided into four subscales: vocal quality, precanonical, canonical, and word. The vocal quality subscale, which is not scored, is utilized to determine whether there are any concerns regarding the quality of the child’s vocalizations (excessive use of pitch variation, growls, glottal stops, or ingressives). This subscale is not further described, as it is beyond the scope of this manuscript. The vocal behaviors queried on the remaining three subscales and their scoring are outlined in Table 2. The precanonical subscale includes six behaviors related to early vocal imitation, vowel use, glide-vowel sequences, and marginal syllables. The canonical subscale queries four behaviors: single canonical syllables, reduplicated canonical sequences, variegated canonical sequences, and jargon-like utterances. The word subscale examines three behaviors: imitation of words, single word use, and use of word combinations.

Table 2.

Vocal behaviors sampled in the precanoncial, canonical, and word subscales of the VDLI-E

| Subscale | Vocal behavior | Scoring |

|---|---|---|

| Precanonical | Attempts to imitate vocalizations | Frequency |

| Egressive production (production of sounds while breathing out) | Frequency | |

| Vowel and glides + vowel production | Frequency | |

| Variety of vowels produced | Inventory | |

| Reduplicated glides + vowel production | Frequency | |

| Marginal syllable production | Frequency | |

| Canonical | Single canonical syllable production—4 items | Frequency |

| Reduplicated canonical sequence production—3 items | Frequency | |

| Variegated canonical sequence production | Frequency | |

| Jargon-like utterance production | Frequency | |

| Word | Single word imitation | Accuracy |

| Variety of words used | Inventory | |

| Variety of word combinations used | Inventory |

The items in the precanonical, canonical, and word subscales are scored using one of three methods. When frequency is of interest, scoring is based on whether the parent reports that a behavior is demonstrated frequently (3 points), sometimes (2 points), rarely (1 point), or never (0 points). When imitation accuracy is of interest, scoring is based on whether the parent reports that the child’s imitation is very close (3 points), somewhat close (2 points), far off (1 point), or the child does not imitate (0 points). When an inventory of vocal or speech behaviors is of interest, scoring corresponds to the number of items reported, with a report of three or more resulting in a score of 3. For example, if the parent reports that the child is not yet using words, the child receives a score of 0 for the word inventory, but a report of five words yields a score of 3. Two behaviors (single canonical syllables and reduplicated canonical sequences) were queried multiple times and thus each behavior is represented as an average of the respective scores. Total scores for each subscale are summed, divided by the total number of possible points (18 for precanonical, 12 for canonical, and 9 for word), and multiplied by 100, yielding a percent score for each subscale. Children with a score above 50% on the word subscale were deemed to be beyond the precanonical stage, thus their precanonical subscale score was replaced with a value of 100. Similarly, children with scores of 100% on the word subscale were deemed to be beyond the canonical stage, thus their canonical score was replaced with a value of 100. This prevented these children from having artificially low scores as a result of replacing these earlier vocalizations types with more advanced vocalizations. The total score was calculated by averaging the percent scores for each of the three subscales.

Audiologic assessment.

Audiologic evaluations were completed for HH children at each test visit by a certified audiologist with pediatric experience and a test assistant. The audiologist attempted to obtain air-conduction and bone-conduction thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz at a minimum by using visual reinforcement audiometry or conditioned play audiometry, depending on the age of the child. When ear-specific thresholds could not be collected using insert earphones, circumaural headphones, or the child’s own earmolds paired with insert earphones, the child’s audiologist provided a copy of the most recent reliable audiogram. To estimate the proportion of the amplified speech spectrum that was audible to the children when they were wearing their hearing aids, real ear speechmapping measurements were completed using the Audioscan Verifit. The aided Speech Intelligibility Index (ANSI, 1997) for the standard male speech signal (carrot passage) at an input level of 65 dB SPL was calculated for both right and left ears, and the higher of these values is considered the better-ear aided Speech Intelligibility Index (BESII).

Auditory development and expressive language measures.

At the 12- and 18-month visits, parents were asked to complete the LittlEars Auditory Questionnaire (Tsiakpini et al., 2004) and the age-appropriate form of the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (MBCDI; Fenson et al., 2007). The LittlEars includes 35 questions regarding auditory and communication behaviors and asks the parent to report whether or not their child demonstrates the behavior, yielding scores of 1 or 0 respectively, for a maximum total score of 35 points. The measure does not provide normative data, thus each child’s performance is represented by a raw score. The MBCDI Words and Gestures form was provided to parents of children 18 months of age and younger and the MBCDI Words and Sentences form was provided to parents of children 19 months of age and older. Both forms include a vocabulary checklist for parents to report the words their child produces. Tallies of words are converted to percentiles based on normative data from the manual.

At the 12-month visit only, the receptive and expressive scales of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995) were administered. The Mullen combines clinician-elicited and parent-reported items. Raw scores are used to calculate an age-normed T-score with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. Of relevance to the present work is the expressive scale T-score. At the 18-month visit only, parents completed the caregiver questionnaire of the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales-Developmental Profile (CSBS-DP; Wetherby & Prizant, 2002). The caregiver questionnaire queries the parent about the child’s abilities in seven areas within three domains: social communication (emotion and eye gaze, communication, and gestures), speech (sounds and words), and symbolic functioning (understanding and object use). Of relevance to the present work is the speech composite, which is represented by an age-normed scaled score with a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 3.

Participants in Each Analysis

To answer the first question, which addresses the sensitivity of the VDLI-E to age for HH children, both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses were conducted. Each of the 80 HH children were represented only once in the cross-sectional analyses. Children who contributed data at 6 months were represented in the 6-month cross-sectional data. Children who only contributed data at 18 months were represented in the 18-month data set. The children who contributed data at both 12 and 18 months, but not 6 months, were randomly assigned to one of the two time points in a manner that allowed for equal group sizes. This yielded data from 22 children in the 6-month age group, and 29 children each for the 12- and 18-month age groups. The longitudinal analyses included the 16 HH children who contributed data at all three time points, all of whom are represented only in the 6-month data for the cross-sectional analyses.

To examine the second question, which explores the relationships of hearing variables to HH children’s VDLI-E scores, all 80 HH children were included and the analyses involved the same VDLI-E data that were utilized in the cross-sectional analysis for Question 1. For the third research question, which examines the sensitivity of the VDLI-E to differences in vocal development between TH and HH 18 month olds, all HH children with a completed VDLI-E at 18-months were included, yielding 18-month VDLI-E data from 74 (of the 80) HH children. Comparisons were made to data for the 21 children with TH whose parents were administered the measure at the child’s 18-month visit. For the fourth research question, in which relationships are examined between VDLI-E scores and scores for the auditory development and expressive language measures, each correlation represents all HH children for whom data was available for both the specified VDLI-E (12 or 18 months) and the respective auditory development or expressive language measure. The n for each correlation is presented in the results.

Results

Question 1: Sensitivity of VDLI-E to Age for HH Children

To determine whether the VDLI-E was sensitive to age for HH children, both cross-sectional and longitudinal data were utilized.

Cross-sectional

To determine whether the age groups were comparable on hearing variables that may contribute to variance in VDLI-E scores, three one-way between-groups analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted with age group (6, 12, 18 months) as the independent variable and each hearing variable (BEPTA, BESII, age at hearing aid fitting) serving as a dependent variable in a separate analysis. BEPTA [F(2, 77) = 0.08, p = .920] and BESII [F(2, 77) = 0.23, p = .798] did not differ between groups. However, age at hearing aid fitting did differ [F(2, 77) = 3.78, p = .027], as the younger children were fit with hearing aids earlier. To determine whether it was necessary to control for age at hearing aid fitting in future analyses, correlations were calculated between age at hearing aid fitting and total score for each of the age groups. No significant correlations were identified (6 month: r = .08, p = .718; 12 month: r = −.11, p = .577; and 18 month: r = .08, p = .685), thus age at hearing aid fitting was not further considered.

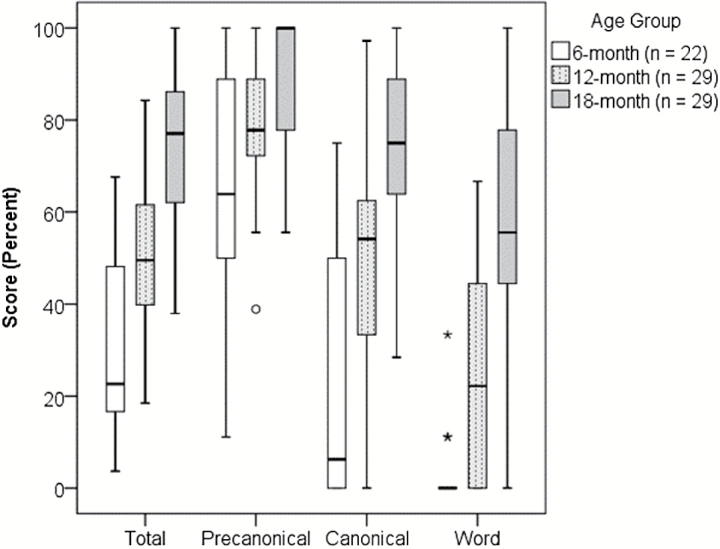

To determine whether the VDLI-E total score was sensitive to differences in age for the cross-sectional data, an ANOVA was conducted with age group (6, 12, 18 months) as the independent variable and total score as the dependent variable. See Table 3 and Figure 2 for descriptive data, between-group comparisons, and boxplots of the cross-sectional total and subscale scores for each age group. There was a statistically significant difference in total score for the three age groups: F(2, 77) = 37.10, p < .001. The effect size, calculated using eta squared, was 0.49. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean scores for all three groups were significantly different at the .01 level. This result supports the prediction that the VDLI-E total score would be sensitive to age using cross-sectional data.

Table 3.

Descriptive data for cross-sectional VDLI-E total and subscale scores by age group (6, 12, and 18 months)

| Score | 6 month (n = 22) | 12 month (n = 29) | 18 month (n = 29) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Total | 30.29 | 18.22 | 50.42 | 17.86 | 73.67 | 17.85 |

| Precanonical | 65.15 | 25.03 | 79.50 | 14.70 | 90.42 | 14.23 |

| Canonical | 23.20 | 27.64 | 47.63 | 23.85 | 73.49 | 19.02 |

| Word | 2.53 | 7.61 | 24.14 | 22.63 | 57.09 | 26.84 |

Figure 2.

Boxplots displaying subscale and total scores for each age group in cross-sectional data for the hard-of hearing-group. The boxes represent the 25th to 75th percentile (interquartile range) and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values, except where indicated by circles and asterisks representing outlier scores. Solid lines represent the medians.

To examine the sensitivity of the subscales to age in the cross-sectional data, two separate analysis techniques were used. Given that the majority of children in the 18-month group were at ceiling on the precanonical subscale and similarly, the majority of children in the 6-month group were at floor on the word subscale, data for these subscales did not meet the assumptions for inclusion in one-way between-groups ANOVA. Thus, for these subscales Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted with age group as the independent variable and either precanonical score or word score as the dependent variable. For the canonical subscale, an ANOVA was conducted with age group as the independent variable and canonical score as the dependent variable. For the precanonical subscale, the Kruskall–Wallis test revealed a statistically significant difference in score across the three age groups, χ2(2, n = 80) = 19.58, p < .001. Post-hoc comparisons using Mann–Whitney U tests indicated that the mean precanonical scores for all three groups were significantly different at the .01 level. For the canonical subscale, the one-way between-groups ANOVA indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in score for the three age groups, F(2, 77) = 29.23, p < .001. The effect size, calculated using eta squared, was 0.43. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean scores for all three groups were significantly different at the .01 level. For the word subscale, the Kruskal–Wallis test also revealed a statistically significant difference in score across the three ages groups, χ2(2, n = 80) = 43.40, p < .001. Post hoc comparisons using Mann–Whitney U tests indicated that the mean word scores for all three groups were significantly different at the .01 level. These results support the prediction that the VDLI-E subscale score would be sensitive to age using cross-sectional data.

Longitudinal

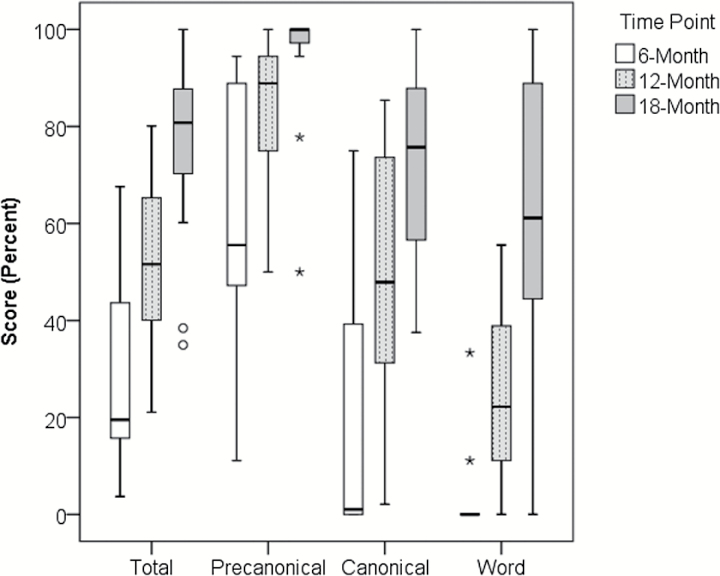

To further examine the sensitivity of the total and subscale scores of the VDLI-E to age for the HH group, longitudinal data were analyzed for the 16 HH children who contributed data at the 6, 12, and 18-month time points. See Table 4 and Figure 3 for descriptive data, between-group comparisons, and boxplots of the longitudinal total and subscale scores by time point. For the total score, a repeated-measures ANOVA with time point as the within-subjects variable was conducted. A significant effect of time point was identified for total score, Wilks’ Lambda = .131, F(2, 14) = 46.36, p < .001. Pairwise comparisons indicated that differences between the three time points in total score were significant at the .01 level for all comparisons. This result supports the prediction that the VDLI-E total score would be sensitive to age using longitudinal data.

Table 4.

Descriptive data for longitudinal VDLI-E total and subscale scores by time point (6, 12, and 18 months)

| Score | 6 month | 12 month | 18 month | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Total | 27.53 | 19.48 | 52.59 | 16.53 | 75.80 | 18.41 |

| Precanonical | 60.42 | 25.89 | 83.68 | 14.27 | 94.73 | 13.22 |

| Canonical | 19.40 | 29.60 | 49.78 | 25.64 | 72.18 | 19.98 |

| Word | 2.78 | 8.61 | 24.31 | 18.69 | 60.42 | 28.10 |

Figure 3.

Boxplots displaying total and subscale scores for each time point for the 16 hard-of-hearing children contributing longitudinal data. The boxes represent the 25th to 75th percentile (interquartile range) and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values, except where indicated by circles and asterisks representing outlier scores. Solid lines represent the medians.

For the subscales, it was again necessary to use two different analysis strategies (parametric and nonparametric) due to normality concerns for the precanonical and word subscales. Friedman tests were utilized to make comparisons across age for the precanonical and word scores, whereas a repeated-measures ANOVA was utilized to examine data for the canonical subscale. For the precanonical subscale, the Friedman test indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in score across the three time points, χ2(2, n = 16) = 24.82, p < .001. Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests indicated that differences between the three time points in precanonical score were significant at the .01 level. For the canonical subscale, a significant effect of time point was also identified, Wilks’ Lambda = .189, F(2, 14) = 30.04, p < .001. Pairwise comparisons indicated that differences between the three time points in canonical score were significant at the .01 level for all comparisons. Finally, for the word subscale, the Friedman test indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in score across the three time points, χ2(2, n = 16) = 28.53, p < .001. Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests indicated that differences between the three time points in word score were all significant at the .01 level. These results support the prediction that the VDLI-E subscale score would be sensitive to age using longitudinal data.

Question 2: Relationships of Severity of Hearing Loss to Outcomes on the VDLI-E

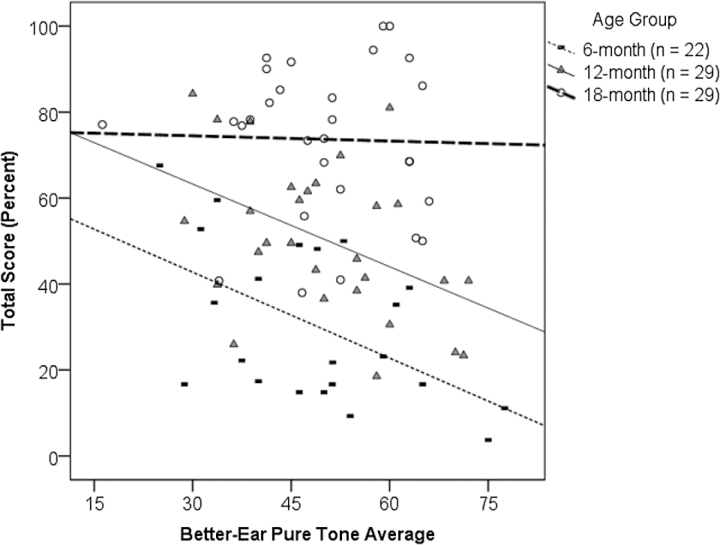

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to examine the contributions of BEPTA to VDLI-E total scores for the full HH group after controlling for the influence of age group. Age group was entered in Step 1. This model was significant, F(1, 79) = 74.89, p < .001, with age group explaining 49.0% of the variance in total score. BEPTA was entered in Step 2. This model was also significant, F(2, 79) = 46.19, p < .001, with BEPTA explaining an additional 5.6% of the variance in total score. See Figure 4 for a scatterplot of the relationship between BEPTA and VDLI-E total score. Regression lines for individual groups show that the relationship between BEPTA and VDLI-E total score was driven by the 6- and 12-month age groups (6 month r = −.53, p = .012, 12 month r = −.45, p = .016). The relationship did not hold for the 18-month age group (r = −.026, p = .892). The results from the 6- and 12-month age groups, but not the 18-month age group, support the prediction that hearing loss would be negatively related to BEPTA.

Figure 4.

Scatterplot of the relationship between better-ear pure tone average and total score for 80 hard-of-hearing children in the cross-sectional data set, with regression lines for each age group.

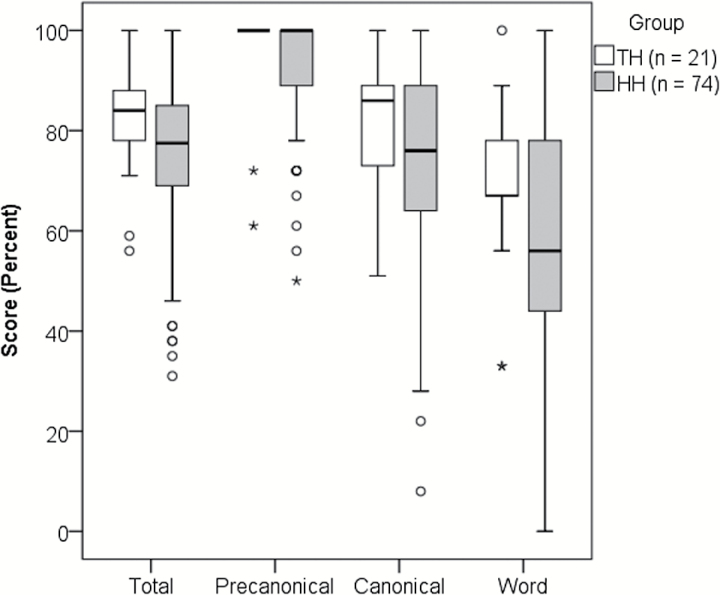

Question 3: Sensitivity of VDLI-E to Differences in Vocal Development Between HH and TH Groups at 18 Months

Given the potential contribution of age to variance in scores, an independent samples t-test was conducted to ensure comparability of the TH and HH 18-month groups on age (TH M = 19.01 months, SD = 1.14; HH M = 19.69, SD = 1.25). The groups did not differ significantly (t = 1.34, p = .183), thus it was not necessary to control for age in further analyses. To compare groups on VDLI-E total score, a t-test with a Satterthwaite adjustment (due to unequal variances between groups) was conducted. Results indicated that the TH group performed significantly better than the HH group (p = .013). See Table 5 and Figure 5 for descriptive data, between-group comparisons, and boxplots of the VDLI-E total and subscale scores for the TH and HH 18-month groups. To compare groups on the precanonical scale, a Mann–Whitney U-test was conducted due to violations of the normality assumption for both groups. Results indicated that the TH group outperformed the HH group, p = .043. To compare groups on the two subscale scores that did not violate assumptions of normality, two separate t-tests were conducted. No significant difference was identified between groups for canonical score (p = .125), but a significant difference was identified for word score (p = .037), with the TH group outperforming the HH group. These results support the prediction that the TH group would outperform the HH group on the VDLI-E total score and word score.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics and between-group comparison of VDLI-E total and subscale scores for TH and HH 18-month olds

| Score | TH group (n = 21) | HH group (n = 74) | Between group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | Test statistics | ||

| Total | 82.05 | 10.61 | 74.28 | 16.75 | t = 2.60a | d = 0.56* |

| Precanonical | 96.83 | 10.18 | 93.02 | 12.10 | U = 595.00 | z = −2.03* |

| Canonical | 80.59 | 13.43 | 73.37 | 20.11 | t = 1.55 | d = 0.42* |

| Word | 68.79 | 16.72 | 56.46 | 25.07 | t = 2.12 | d = 0.58* |

aIndicates a Satterthwaite adjustment in the t-test.

*p < .05.

Figure 5.

Boxplots displaying total and subscale scores for typically hearing (TH) and hard of hearing (HH) 18-month groups. The boxes represent the 25th to 75th percentile (interquartile range) and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values, except where indicated by circles and asterisks representing outlier scores. Solid lines represent the medians.

Question 4: Relationships of VDLI-E Scores With Concurrent Measures of Communication Abilities for HH Children at 12 and 18 Months

Pearson correlation coefficients were explored between total scores on the VDLI-E and the available measures of auditory development, expressive vocabulary, and overall expressive language at 12 and 18 months for the HH group. For each correlation, all HH children who contributed data for the VDLI-E and the communication measure at the specified age were included. See Table 6 for descriptive information regarding performance on the measures and the numbers of children contributing data for each explored relationship. At 12 months, total score was significantly correlated with scores for all measures: LittlEars (r = .49, p < .001), MBCDI words produced (r = .58, p < .001), and Mullen expressive scale (r = .72, p < .001). Similarly, at 18 months, total score was significantly correlated with scores for all measures: LittlEars (r = .61, p < .001), MBCDI words produced (r = .67, p < .001), and the speech composite of the CSBS-DP (r = .79, p < .001). These results support the prediction that VDLI-E scores would be strongly related to concurrent measures of early communication abilities.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics for hard-of-hearing children completing the VDLI-E and one or more concurrent measures of communication abilities

| Measure | 12 months | 18 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |

| LittlEars (raw score) | 49 | 22.92 | 5.32 | 68 | 29.79 | 4.96 |

| MBCDI words produced (percentile) | 49 | 42.68 | 27.33 | 68 | 30.74 | 23.74 |

| Mullen expressive scale (T-score) | 53 | 44.02 | 14.62 | |||

| CSBS-DP speech composite (scaled score) | 70 | 9.29 | 2.74 | |||

Discussion

This study examined the use of the VDLI-E with young children who are HH, including whether the measure was sensitive to age and hearing and whether their VDLI-E performance was related to performance on other measures of early communication abilities. As predicted, the VDLI-E was found to be sensitive to age (6, 12, and 18 months) for HH children, both when examined with cross-sectional and longitudinal data. Additionally, the measure was found to be sensitive to the effects of hearing loss on early vocal development, as evidenced by the relationship between VDLI-E scores and BEPTA and the differences between scores for 18-month-old children who are HH and TH. Strong, positive relationships were also identified between the performance of HH children on the VDLI-E and other measures of early communication skills. These findings provide preliminary support for the utility of this measure in monitoring the impact of early auditory experiences on vocal development for 6- to 18-month-old children who are HH.

Another positive finding was that the measure was generally sensitive to severity of hearing loss for the HH children, with significant correlations between BEPTA and VDLI-E scores at the 6- and 12-month visits. It is unclear why the relationship between BEPTA and VDLI-E scores was not evident for children at the 18-month visit. In addition to the finding that severity of hearing loss was related to vocal development for younger children in the present work, other recent studies, including studies from the OCHL project with 2- and 3-year-old HH children, have found relationships between severity of hearing loss and speech development (Ambrose et al., 2014; Tomblin, Oleson, Ambrose, Walker, & Moeller, 2014; Wiggin, Sedey, Awad, Bogle, & Yoshinaga-Itano, 2013). These findings would lead to the expectation that this relationship would also exist at 18 months. Thus, this unexpected finding may be a result of the VDLI-E items for older children not being sensitive enough to the effects of varying degrees of hearing loss. Further work should examine whether modification of the word section to capture more variance in development results in the measure being sensitive to differences in hearing loss severity at this age, or perhaps why this relationship may not exist at this point in development.

Although severity of hearing loss and VDLI-E scores were not significantly correlated at 18 months, the measure was sensitive to hearing status at this age, with the TH group outperforming the HH group. This finding indicates that even when children with mild-to-severe hearing loss have the benefit of early hearing aid fittings and enrollment in early intervention, the resulting increases in access to auditory input and feedback are not sufficient for all children to achieve typical vocal development by 18 months of age. This finding fits with predictions that were made based on the inconsistent access hypothesis proposed by the OCHL team. The hypothesis posits that children who are HH experience limitations in access to the linguistic input that shapes pre-lexical and lexical speech and language development (Moeller & Tomblin, 2015). Although access to well-fit hearing aids should serve to increase children’s access to linguistic input, these HH children still have early auditory experiences that differ as compared to their peers with TH. Given the importance of access to auditory input and feedback for vocal development (Koopmans-van Beinum et al., 2001), it is unsurprising that HH children are at risk for phonological delays. However, it should be noted that although the difference between groups was significant, the effect size for total VDLI-E scores was only .56, with the mean score of the HH group falling less than one standard deviation (.73) below the TH group mean. It is difficult to compare the magnitude of this difference to the difference that might have existed for previous generations of HH children, as previous generations were not typically identified until much later, thus research on their early vocal development is sparse. Consequently, we are just beginning to learn about how auditory experience and early vocal development are impacted by early identification and intervention. It is possible that the relatively small difference between groups is a reflection of some children experiencing positive benefits from early intervention services and early hearing aid fitting, the latter of which occurred at an average of approximately 5 months of age for this group of 18-month-old HH children.

Scores on the VDLI-E for 12- and 18-month-old HH children were found to be strongly correlated (rs = 0.49–0.67) with scores on concurrent measures of auditory development (LittlEars) and expressive vocabulary (MBCDI words produced). Additionally, very strong correlations (rs = 0.72 and 0.79) were identified between VDLI-E scores and concurrent measures of overall expressive language (Mullen expressive scale and CSBS-DP speech composite). The magnitude of these correlations indicates that these assessments capture similar, but not identical, information about children’s early communication development. Given that the VDLI-E measures abilities most similar to those assessed by the overall measures of expressive language, one of which relies heavily on clinician observation and elicitation as opposed to parent report, the very strong correlations lend support to the argument that parents are able to reliably report on their child’s early vocal behaviors when provided with supports of the nature provided by the VDLI-E (e.g., audio samples of queried behaviors paired with non-technical language). Additionally, the strong relationships with LittlEars scores lends support to the concept that early vocalizations are reflective of the auditory abilities of HH children (Kishon-Rabin et al., 2005, 2009). These relationships are similar, albeit lower, than those found by Kishon-Rabin et al. (2005) between scores for children with TH on the PRISE and on a questionnaire that queries parents about their child’s everyday listening behaviors.

Future Research and Tool Development

The present work provides preliminary support for the utility of the VDLI-E with HH children, and suggests the appropriateness of pursuing additional steps in revising and validating the instrument.

Future directions: Potential data-driven revisions to the scale

As highlighted earlier, the VDLI-E could be improved in numerous ways. Although not unexpected, floor effects were present for the 6-month age group on the word subscale and ceiling effects were present for the 18-month age group on the precanonical subscale. Given that these effects were anticipated based on the developmental stages of these age groups, it may be warranted to establish basal and ceiling rules that allow for only the relevant subscales to be administered to each child. Additionally, a slight ceiling effect on the total score was identified for some children at 18 months. Thus, efforts should be made to include additional items, especially at the upper end of the scale, and to modify scoring to ensure more sensitivity to individual differences (e.g., for inventory items, the maximum score is currently assigned for use of three or more vowels or words, but this could be broadened so that scoring captures variance between children who have more than three vowels or words). These changes may also allow the measure to be more sensitive to severity of hearing loss for children at the upper end of the age range for the measure.

Future directions: Validity, reliability, and sensitivity

After the measure is revised, work will be needed to examine the validity, reliability, and sensitivity of the measure. Validity analyses should include concurrent validity with another measure of early vocal development and predictive validity for persistence of delays or lack thereof in speech development. Additionally, although the vocal quality items were added to the measure with the hypothesis that frequent demonstration of these features at specific time points in development may serve as red flags for HH children who are most at risk for later delays in speech and language development, the validity of their inclusion has yet to be explored.

Reliability of parent report utilizing this tool should also be explored, with comparisons made to the current gold-standard used in research programs, which is clinician evaluation of observed vocal behaviors. One innovative strategy for comparing reliability of parent report to clinician evaluation being explored by this team involves collecting naturalistic recordings of children in their home environments. This is now feasible due to recent technological advancements, including availability of the Language Environment Analysis (LENA) software and the corresponding digital language processor, which is a 2 ounce device that can be worn by children to collect 16-hr audio recordings (LENA Foundation, Boulder, CO). This type of recording would allow the clinical judge to document children’s observed vocal behaviors and judge the quality of their vocalizations in audio samples collected in the same settings where parents are observing their child’s vocal behaviors. This strategy may be more ecologically valid than evaluations that occur in clinical settings, where children may not demonstrate the wide array of vocalizations they use at home. This analysis could also lead to further revision of the model; if parent-report is generally reliable, but one or more items yields poorer-than-expected reliability, an argument could be made for eliminating those items from the interview.

The VDLI-E was found to be sensitive to age at three discrete points in time and to hearing status at one age in the present work. However, further investigations involving larger samples are needed to ensure that the measure is sensitive to narrower age categories and hearing status across the full range of ages for which the measure was designed for use (6–21 months). As a first step toward these goals the research team recently collected normative data with 160 children with TH across the measure’s targeted age range. Analyses of these data are underway.

Future directions: Broadening the measure’s utility

Another future direction is to increase flexibility of the format of administering the interview. In the present work, the measure was administered in a face-to-face setting with parents. However, the utility of the measure would be broadened if it could be administered at a distance, thus allowing research programs to use the measure to reach larger and more varied participant populations and allowing clinicians to use the measure when providing teleintervention services. Thus, the potential for presentation of the PowerPoint slides and audio samples via the web or an app is being explored.

Although this measure was designed to assess the impact of auditory experience on the vocal development of children who are HH, the measure may have both clinical and research utility for other populations. These include not only children who are deaf and may use cochlear implants, but also children who may be at risk for delays in vocal development secondary to other concerns, such as a premature birth or brain injury. Thus, the value of using this measure with other populations should be explored. Similarly, further development of this measure to allow it to be more readily used by professionals working with young children is warranted. This includes creation of a manual with descriptions of how to administer, score, and interpret the measure and development of professional learning modules with information on how to utilize the results to select and monitor progress toward intervention goals.

Summary

The findings of the present work suggest that early auditory experience contributes to the vocal development of infants and support the use of the VDLI-E to track vocal development for infants and toddlers who are HH. Future work will further examine the reliability and validity of a revised version of the VDLI-E.

Funding

National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders [R01DC009560, R01DC006681, and R03DC012647].

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest were reported.

Acknowledgments

We thank the children and families who participated in this project. We thank Sandie Bass-Ringdahl for her contributions to development of the VDLI-E and Carol Stoel-Gammon and David Ertmer for their helpful comments on the measure. In addition, gratitude for statistical support is extended to Ryan McCreery and Jacob Oleson.

References

- Ambrose S. E. Unflat Berry L. M. Walker E. A. Harrison M. Oleson J., & Moeller M. P (2014). Speech sound production in 2-year-olds who are hard of hearing. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23, 91–104. doi:10.1044/2014_AJSLP-13–0039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANSI (1997). Methods for calculation of the speech intelligibility index. Technical Report S3.5-1997. New York, NY: American National Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Bates E. Bretherton I., & Snyder L (1991). From first words to grammar: Individual differences and dissociable mechanisms. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bates E. Dale P. S., & Thal D (1995). Individual differences and their implications for theories of language development. In Fletcher P., MacWhinney B. (Eds.), The handbook of child language (pp. 96–151). Oxford, UK: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Itzhak D., Greenstein T., Kishon-Rabin L. (2014). Parent report of the development of auditory skills in infants and toddlers who use hearing aids. Ear and Hearing, 35, e262–e271. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantle-Moore R. (2004). Infant monitor of vocal production. North Rocks, New South Wales, Australia: Royal Institute for Deaf and Blind Children. [Google Scholar]

- Cantle Moore R. (2014). The infant monitor of vocal production: Simple beginnings. Deafness & Education International, 16, 218–236. doi:10.1179/1464315414Z.00000000067 [Google Scholar]

- Dale P. S. (1991). The validity of a parent report measure of vocabulary and syntax at 24 months. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34, 565–571. doi:10.1044/ jshr.3403.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers R. E., & Oller D. K (1994). Infant vocalizations and the early diagnosis of severe hearing impairment. Journal of Pediatrics, 124, 199–203. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(94)70303–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg L. S., Widen J. E., Yoshinaga-Itano C., Norton S., Thal D., Niparko J. K., Vohr B. (2007). Current state of knowledge: Implications for developmental research–key issues. Ear and Hearing, 28, 773–777. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e318157f06c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertmer D. J., & Iyer S. N (2010). Prelinguistic vocalizations in infants and toddlers with hearing loss: Identifying and stimulating auditory-guided speech development. In Marschark M., Spencer P. E. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education (pp. 360–375). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ertmer D. J., Jung J. (2012). Prelinguistic vocal development in young cochlear implant recipients and typically developing infants: year 1 of robust hearing experience. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 17, 116–132. doi:10.1093/deafed/enr021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertmer D. J. Strong L. M., & Sadagopan N (2003). Beginning to communicate after cochlear implantation: Oral language development in a young child. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46, 328–340. doi:10.1044/1092–4388(2003/026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertmer D. J., Young N. M., Nathani S. (2007). Profiles of vocal development in young cochlear implant recipients. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 393–407. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2007/028) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L. Marchman V. A. Thal D. Dale P. S. Reznick J. S., & Bates E (2007). MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: User guide and technical manual. 2nd edn. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S. N., Oller D. K. (2008). Prelinguistic vocal development in infants with typical hearing and infants with severe-to-profound hearing loss. The Volta Review, 108, 115–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishon-Rabin L. Taitelbaum-Swead R. Ezrati-Vinacour R., & Hildesheimer M (2005). Prelexical vocalization in normal hearing and hearing-impaired infants before and after cochlear implantation and its relation to early auditory skills. Ear and Hearing, 26(4 Suppl.), 17S–29S. doi:00003446-200508001-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishon-Rabin L. Taitlebaum-Swead R., & Segal O (2009). Prelexical infant scale evaluation: From vocalization to audition in hearing-impaired infants. In Eisenberg L. S. (Ed.), Clinical management of children with cochlear implants (pp. 325–368). San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans-van Beinum F. J. Clement C. J., & van den Dikkenberg-Pot I (2001). Babbling and the lack of auditory speech perception: A matter of coordination? Developmental Science, 4, 61–70. doi:10.1111/1467–7687.00149 [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein R. (1984). Predicting school performance of preschool children from parent reports. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 12, 79–94. doi:10.1007/BF00913462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller M. P. Bass-Ringdahl S. Ambrose S. E. VanDam M., & Tomblin J. B (2011). Understanding communication outcomes: New tools and insights. In Seewald R. C., Bamford J. M. (Eds.), A sound foundation through early amplification: Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference (pp. 245–259). Chicago, IL: Phonak AG. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller M. P. Hoover B. Putman C. Arbataitis K. Bohnenkamp G. Peterson B., … Stelmachowicz P (2007. a). Vocalizations of infants with hearing loss compared with infants with normal hearing: Part I–phonetic development. Ear and Hearing, 28, 605–627. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e31812564ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller M. P. Hoover B. Putman C. Arbataitis K. Bohnenkamp G. Peterson B., … Wood S (2007. b). Vocalizations of infants with hearing loss compared with infants with normal hearing: Part II—Transition to words. Ear and Hearing, 28, 628–642. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e31812564c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller M. P., & Tomblin J. B (2015). An introduction to the Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss study. Ear and Hearing, 36(Suppl. 1), 4S–13S. doi:10.1097/ AUD.0000000000000210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. A., & Bass-Ringdahl S (2002). Role of infant vocal development in candidacy for and efficacy of cochlear implantation. The Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 189, 52–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen M. E. (1995). Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Nathani S., Ertmer D. J., Stark R. E. (2006). Assessing vocal development in infants and toddlers. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 20, 351–369. doi:10.1080/02699200500211451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathani S., Oller D. K. (2007). On the robustness of vocal development: An examination of infants with moderate-to-severe hearing loss and additional risk factors. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 50, 1425–1444. doi:10.1044/1092–4388(2007/099) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K. (1973). Structure and strategy in learning to talk. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 38(1–2, Serial No. 149). doi:10.2307/1165788 [Google Scholar]

- Oller D. K. (2000). The emergence of the speech capacity. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Oller D. K., & Eilers R. E (1988). The role of audition in infant babbling. Child Development, 59, 441–449. doi:10.2307/1130323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oller D. K. Eilers R. E., & Basinger D (2001). Intuitive identification of infant vocal sounds by parents. Developmental Science, 4, 49–60. doi:10.1111/1467–7687.00148 [Google Scholar]

- Oller D. K. Eilers R. E. Neal A. R., & Schwartz H. K (1999). Precursors to speech in infancy: The prediction of speech and language disorders. Journal of Communication Disorders, 32, 223–246. doi:10.1016/S0021-9924(99)00013-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L., & Alley A (2001). Validation of the Language Development Survey (LDS): A parent report tool for identifying language delay in toddlers. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 44, 434–445. doi:10.1044/1092–4388(2001/035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb M. P. Bauer H. R., & Tyler A. A (1994). A quantitative analysis of the single-word stage. First Language, 14, 37–48. doi:10.1177/014272379401404003 [Google Scholar]

- Schauwers K. Gillis S. Daemers K. De Beukelaer C., & Govaerts P. J (2004). Cochlear implantation between 5 and 20 months of age: The onset of babbling and the audiologic outcome. Otology & Neurotology, 25, 263–270. doi:10.1097/00129492-200405000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark R. E. (1980). Stages of speech development in the first year of life. In Yeni-Komshian G. Kavanagh J., & Ferguson C. A. (Eds.), Child phonology (Vol. 1, pp. 73–90). New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R. E. (1983). Phonatory development in young normally hearing and hearing-impaired children. In Hochberg I. Levitt H., & Osberger M. J. (Eds.), Speech of the hearing-impaired: Research, training, and personnel preparation (pp. 251–266). Baltimore, MD: University Park. [Google Scholar]

- Stoel-Gammon C. (1988). Prelinguistic vocalizations of hearing-impaired and normally hearing subjects: A comparison of consonantal inventories. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 53, 302–315. doi:10.1044/jshd.5303.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoel-Gammon C. (2011). Relationships between lexical and phonological development in young children. Journal of Child Language, 38, 1–34. doi:10.1017/S0305000910000425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoel-Gammon C., & Otomo K (1986). Babbling development of hearing-impaired and normally hearing subjects. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 51, 33–41. doi:10.1044/jshd.5101.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin J. B., Oleson J. J., Ambrose S. E., Walker E., Moeller M. P. (2014). The influence of hearing aids on the speech and language development of children with hearing loss. JAMA Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, 140, 403–409. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2014.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin J. B. Walker E. A. McCreery R. W. Arenas R. M. Harrison M., & Moeller M. P (2015). Outcomes of children with hearing loss: Data collection and methods. Ear and Hearing, 36(Suppl. 1), 14S–23S. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiakpini L. Weichbold V. Kuehn-Inacker H. Coninx F. D’Haese P., & Almadin S (2004). LittlEars Auditory Questionnaire. Innsbruck, Austria: MED-EL. [Google Scholar]

- von Hapsburg D., Davis B. L. (2006). Auditory sensitivity and the prelinguistic vocalizations of early-amplified infants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 809–822. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2006/057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby A. M., & Prizant B. M (2002). Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales—Developmental profile. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggin M. Sedey A. L. Awad R. Bogle R. M., & Yoshinaga-Itano C (2013). Emergence of consonants in young children with hearing loss. The Volta Review, 113, 127–148. [Google Scholar]