Abstract

Introduction:

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Smoking Initiative has developed item banks for assessing six smoking behaviors and biopsychosocial correlates of smoking among adult cigarette smokers. The goal of this study is to evaluate the performance of the Spanish version of the PROMIS smoking item banks as compared to the original banks developed in English.

Methods:

The six PROMIS banks for daily smokers were translated into Spanish and administered to a sample of Spanish-speaking adult daily smokers in the United States (N = 302). We first evaluated the unidimensionality of each bank using confirmatory factor analysis. We then conducted a two-group item response theory calibration, including an item response theory-based Differential Item Functioning (DIF) analysis by language of administration (Spanish vs. English). Finally, we generated full bank and short form scores for the translated banks and evaluated their psychometric performance.

Results:

Unidimensionality of the Spanish smoking item banks was supported by confirmatory factor analysis results. Out of a total of 109 items that were evaluated for language DIF, seven items in three of the six banks were identified as having levels of DIF that exceeded an established criterion. The psychometric performance of the Spanish daily smoker banks is largely comparable to that of the English versions.

Conclusions:

The Spanish PROMIS smoking item banks are highly similar, but not entirely equivalent, to the original English versions. The parameters from these two-group calibrations can be used to generate comparable bank scores across the two language versions.

Implications:

In this study, we developed a Spanish version of the PROMIS smoking toolkit, which was originally designed and developed for English speakers. With the growing Spanish-speaking population, it is important to make the toolkit more accessible by translating the items and calibrating the Spanish version to be comparable with English-language scores. This study provided the translated item banks and short forms, comparable unbiased scores for Spanish speakers and evaluations of the psychometric properties of the new Spanish toolkit.

Introduction

The National Institute of Health (NIH) has supported the building of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) using modern psychometric techniques based on Item Response Theory (IRT). PROMIS tools provide researchers and clinicians with reliable, precise measures of patient-reported health status for physical, mental, and social well-being by asking what patients are able to do and how they feel. The PROMIS Smoking Initiative1 has developed an assessment toolkit that enables efficient measurement of six distinct, unidimensional constructs of central importance to smoking research on current adult cigarette smokers: Nicotine Dependence,2 Coping Expectancies,3 Positive Emotional and Sensory Expectancies,4 Negative Health Expectancies,5 Negative Psychosocial Expectancies,6 and Social Motivations.7 Development of the smoking item banks involved extensive qualitative1 and quantitative analyses8 of an English-speaking sample (4201 daily smokers and 1183 nondaily smokers). Fixed-length short forms (SFs) and dynamic computer adaptive test (CAT) administrations are available for all banks.9

This toolkit was originally designed and developed for English speakers. However, individuals of Hispanic origin constitute the largest racial/ethnic minority group in the United States, and one that is projected to comprise 28% of the population by 2060.10 Smoking is a significant health concern among Hispanic adults in the United States, with 17% of men and 7% of women being current smokers.11 Furthermore, one-third of all Hispanic adults in the United States report not speaking English very well12; worldwide, Spanish is spoken by more individuals than English.13 Thus, it is important to make the toolkit more accessible for the Spanish-speaking population by translating the items and calibrating the Spanish version to be comparable with English-language scores.

Many PROMIS measures have been translated into Spanish (eg, see a 2013 study by Paz et al.14 for evaluating the PROMIS physical functioning items in Spanish). This process involves not only the translation from English, but also the analytic evaluation of cross cultural differences to ensure that the items function in a similar manner across the different languages. For example, due to possible differences in social norms regarding smoking or quitting behaviors across different cultures,15 an item assessing the expected social benefits of smoking may be rated higher by Spanish-speaking smokers than English-speaking smokers, given the same level of social motivation for smoking. If cultural differences such as these are unaccounted for, they may possibly bias scores for Spanish-speaking participants. In this study, we aim to evaluate the equivalence of Spanish and English item banks via IRT and Differential Item Functioning (DIF) detection, to provide a means of computing comparable unbiased scores for Spanish speakers, and evaluate the psychometric properties of the Spanish-language scores.

Method

Data Sources and Measures

Samples

The sample of Spanish-speaking daily smokers (N = 302) was recruited through the YouGov panel, a proprietary opt-in survey panel comprised of 1.2 million US residents who have agreed to participate in YouGov’s Web surveys. Panel members are recruited by a number of methods to ensure the panel’s diversity, including Web advertising campaigns (public surveys), permission-based email campaigns, partner sponsored solicitations, telephone-to-Web recruitment (RDD) based sampling, and mail-to-Web recruitment (voter registration based sampling). Participants are not paid to join the YouGov panel, but do receive incentives through a loyalty program to take individual surveys. Sample recruitment was targeted to reflect the demographic composition of Spanish-speaking US adult smokers in terms of gender, race/ethnicity, and age. Individuals were eligible if they were 18 years or older, had been smoking for at least a year, had smoked in the past 30 days, did not have plans to quit in the next 30 days, and were Spanish-speaking. Although bi-lingual (Spanish and English) respondents were allowed, participants were not eligible if they responded that they spoke English “well” or “extremely well” as the goal was to enroll participants who were primarily Spanish speakers. All participants reported their ethnicity as Hispanic; when asked about their main racial group, 72.9% self-identified as white, 4.3% as black, 0.7% as Asian, and 22.2% as “other.” They completed Spanish versions of the six PROMIS daily smoking banks via the internet.

The comparison sample of English-speaking daily smokers was obtained from the sample used to develop the PROMIS smoking item banks (N = 4201). This sample was recruited by Harris Interactive through their online panel membership with assessments completed via the Internet.16 Similar to the Spanish-speaking sample, recruitment was targeted to reflect the demographic composition of US adult smokers in terms of gender, race/ethnicity, and age. Eligibility criteria were the same as for the Spanish-speaking sample, except that participants were English-speaking.

Demographic and smoking characteristics of the two samples are displayed in Table 1. As can be seen, statistically significant differences in some basic demographic characteristics and smoking patterns between the Spanish- and English-speaking samples were observed. For example, the English-speaking sample had a higher mean age (46.4 years) and a higher proportion of female participants (54.8%) than the Spanish-speaking sample (mean age = 37.4 years and 41.7% female, both P < .01). The English-speaking sample also included more individuals who smoked at least a ½ pack of cigarettes per day in the past 30 days (about 70%) than those in the Spanish-speaking sample (about 35%, P < .01).

Table 1.

Demographic and Smoking Characteristics of the English- and Spanish-Speaking Daily Smoker Samples

| Characteristic | English sample (N = 4201) | Spanish sample (N = 302) | Difference test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 46.4 (11.6) | 37.43 (10.96) | P < .0001 |

| Female, % | 54.8 | 41.7 | P < .0001 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||

| Hispanic | 11.3 | 100 | P < .0001 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 72.2 | ||

| African American | 12.1 | ||

| Asian | 1.76 | ||

| Other | 2.62 | ||

| Education, % | |||

| <High school graduate | 3.1 | 8 | P < .0001 |

| High school graduate | 16.5 | 29.6 | |

| Some college | 38.2 | 17.9 | |

| AA degree | 12.5 | 12 | |

| BA/BS degree | 17.5 | 16.6 | |

| Graduate degree | 12.3 | 16 | |

| Employment, % | |||

| Full-time | 52.9 | 57.3 | P < .0001 |

| Part-time | 12.2 | 7.6 | |

| Unemployed/retired/student/homemaker | 34.2 | 35.1 | |

| Missing | 0.8 | ||

| Marital status, % | |||

| Never married | 20.5 | 19.7 | P < .0001 |

| Married/ civil union/living with partner | 57.7 | 71 | |

| Divorced/ separated/ widowed | 21.8 | 9.3 | |

| Income, % | |||

| <$20 000 | 22.5 | 27.5 | P < .0001 |

| $20 000–$49 999 | 32.3 | 43.7 | |

| $50 000–$99 999 | 33.8 | 23.7 | |

| ≥$100 000 | 11.5 | 5.1 | |

| Smoking patterns | |||

| Number of days smoked in past 30 days, % | |||

| <1 per day | 0.2 | 3.6 | P < .0001 |

| 1 per day | 0.6 | 9.6 | |

| 2–5 per day | 7.4 | 29.5 | |

| 6–10 per day | 22 | 22.2 | |

| 11–20 per day | 47.3 | 25.2 | |

| >20 per day | 22.6 | 9.9 | |

| Interest in quitting, % | |||

| Not at all | 18.5 | 9.6 | P < .001 |

| A little bit | 19.8 | 20.9 | |

| Somewhat | 25.9 | 25.8 | |

| Quite a bit | 21 | 29.5 | |

| Very much | 14.8 | 14.2 | |

| Recency (when was the last attempt to quit for longer than a day), % | |||

| Didn’t quit | 22.5 | 17.5 | P < .0001 |

| Within the past month | 2 | 34.1 | |

| 2–5 months ago | 8.6 | 23.2 | |

| 6–11 months ago | 11.1 | 9.6 | |

| A year or more ago | 55.8 | 15.6 | |

Measures

Translation. All survey materials were translated into Spanish following the PROMIS translation guidelines.17 Prior to translation, we first conducted two focus groups with 19 monolingual Spanish-speaking participants with varying levels of smoking experience. The focus groups explored the need for new item content and identified terms that are most used in Spanish to inform the translation and ensure harmonization. Focus group participants were recruited, screened, and scheduled by a recruitment firm in California. In order to be eligible for the focus group, individuals had to be monolingual Spanish-speaking smokers between 18 and 64 years of age. The recruiter used a scripted recruitment/screener guide for recruitment and ensured that participants varied by education, Latino sub-group, gender, and smoking status (nondaily, moderate, and heavy smokers). After obtaining informed consent, respondents were asked to complete a brief demographic information form prior to the discussion. The focus group moderator, who was fully bilingual, generally followed a scripted focus group discussion guide; however, she probed further as necessary to obtain as much information as possible. The focus group sessions were audiotaped. Respondents were paid $100 for their participation.

Following the focus groups, our translation approach began with two independent forward translations of the English item set conducted by professional translators who were native speakers (one from Mexico, the other from Venezuela) to translate independently from the source English document to Spanish, using broadcast Spanish to capture the words or phrases used by the majority of the Spanish-speaking population so as to avoid regional wording and linguistic differences in different ethnicities and targeting an educational level of 6th to 8th grade. Next, a review committee comprised of these two professional translators and a bilingual research team member conducted an item-by-item review to resolve any translation discrepancies and to ensure consensus on key items. If no consensus was obtained among the three members on a given item, a second bilingual research team member was consulted and provided input. Items that were problematic (term or concept) were flagged for additional cognitive testing.

We conducted cognitive interviews with 20 Spanish-speaking smokers using a protocol similar to that used for the English cognitive interviews.1 For items that had been flagged for further testing due to problematic wording or concepts we added additional probes to test variants in wording (eg, for “coping” we used “lidiar” and “manejar”; for “daily activities” we used “actividades diarias” and “actividades cotidianas” to explore potential differences in understanding and meaning). Two professional translators and two bilingual research team members met to review the findings from the cognitive interviews and to further refine some questions to finalize the Spanish translation before it was fielded.

Item Banks. The item banks include Nicotine Dependence (27 items; α = 0.98)2 which assesses craving, withdrawal that occurs upon brief cessation of smoking, smoking temptations, compulsive use, and tolerance (eg, “When I run out of cigarettes, I find it almost unbearable”); Coping Expectancies (15 items; α = 0.97)3 which assesses smoking as a means of coping with negative affect and stress (eg, “I rely on smoking to deal with stress”); Positive Emotional and Sensory Expectancies (16 items; α = 0.97)4 which assesses perceptions of improved cognitive abilities, positive affective states, and pleasurable sensorimotor sensations due to smoking (eg, “I feel better after smoking a cigarette”); Negative Health Expectancies (19 items; α = 0.95)5 which assesses perceptions of current and long-term consequences of smoking on one’s health (eg, “Smoking is taking years off my life”); Negative Psychosocial Expectancies (20 items; α = 0.95)6 which assesses social disapproval of smoking, normative values associated with smoking, and negative beliefs about one’s appearance when smoking (eg, “People think less of me when they see me smoking”); and Social Motivations (12 items; α = 0.92)7 which assesses the expected social benefit of smoking and the social cues that induce cigarette craving (eg, “Smoking makes me feel better in social situations”). Items were rated on 5-point quantity (1 = not at all to 5 = very much) or frequency (1 = never to 5 = always) scales.

Smoking and Quitting History. All respondents completed three items that assessed their smoking and quitting history. Average number of cigarettes smoked per day in the past 30 days was rated on a 7-point scale (1 = less than one in the past 30 days to 7 = more than 20 per day). Interest in quitting was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = very much). Recency of most recent quit attempt was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = didn’t quit, 2 = within the past month to 5 = a year or more ago).

Statistical Analysis

Unidimensionality

We first evaluated the unidimensionality of each Spanish smoking item bank by fitting one-factor models to the Spanish-speaking sample data in IRTPRO.18 We used the root mean square error of approximation and non-normed fit index values to evaluate fit of these models. Preferably, root mean square error of approximation values <0.08 indicate adequate fit,19,20 and values of non-normed fit index ≥ 0.95 are considered reflective of good fit.21

Spanish Item Bank Calibrations

For each smoking domain, a two-group (English and Spanish) IRT DIF analysis with full-information estimation was used to concurrently calibrate the smoking items and evaluate the equivalence of the parameters generated for the English-speakers and the Spanish-speakers. The two-group IRT-based DIF model used the English-speaking group as the reference group (with an assumed standard normal distribution). The Spanish-speaking group was treated as the focal group where the domain means and standard deviations were freely estimated. Model estimation generated a set of unique item parameters for each Spanish item bank item. The same procedure was repeated for each domain.

Identifying Items With Nonignorable DIF

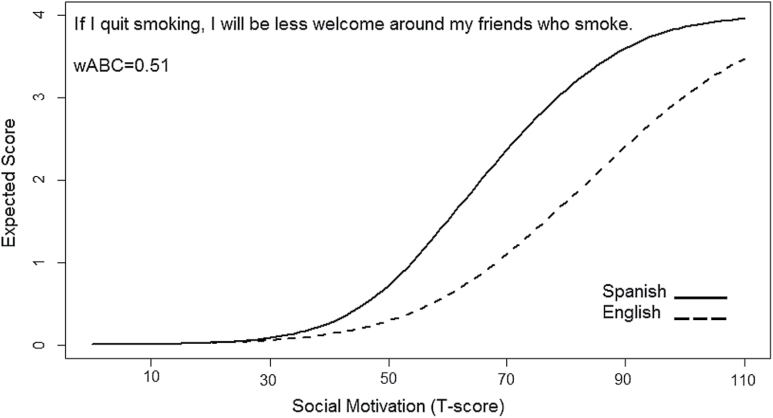

The two-group IRT model described above was used to identify items with potential DIF according to language (English vs. Spanish). DIF occurs when the probability of responding to an item is more different across groups than expected given domain mean differences across groups. We quantified DIF using the weighted Area Between the expected score Curve (“wABC”)22 which was calculated using the computer software R.23 We also generated item-level DIF plots to visually illustrate the area between the expected score curves of the two groups.24 After visually examining the plots, we used wABC > 0.4 as the guideline to flag items with substantial DIF. For those items identified as displaying nonignorable language DIF, we generated unique IRT item parameters based on the two-group DIF model. For items that did not display problematic DIF, the IRT item parameters from the original English calibration were imposed. This process allowed the DIF items to be retained while producing unbiased score estimates.25

Generating Scores and Obtaining Initial Descriptive Information

Following PROMIS conventions,26 expected a posteriori (EAP) scores for each item bank were placed on a T-score metric (mean = 50, standard deviation = 10). Since the Spanish item banks were calibrated with the English-speaking daily smokers as the reference population, the means and standard deviations for each Spanish item bank were uniquely estimated and used as priors during the scoring procedures. Full bank scores were calculated using response pattern scoring from IRTPRO. We also generated Spanish domain SFs using the same items as those in the existing English SFs. However, the scoring of the Spanish SFs differs due to (1) new item parameters for the DIF items and (2) newly estimated domain means and standard deviations for the Spanish-speaking population. SF questionnaires and score translation tables for the Spanish translation are provided in the online Supplementary Material and are also posted on the project website (www.rand.org/health/projects/promis-smoking-initiative.html).

Preliminary validity evidence for the Spanish full bank and SF scores was evaluated by obtaining SF reliabilities, correlations among the bank scores as well as with the measures of smoking quantity, quitting interest, and recency of quit attempts.

Results

Unidimensionality

The one-factor models for each Spanish-language item bank resulted in root mean square error of approximations ranging from 0.06 to 0.10 and non-normed fit indices were 0.93 or above. Although not all indices reached the strict cut-off criteria, taken together, the factor analytic results of each of the six translated banks support the essential unidimensionality required for IRT analysis.

Spanish Item Bank Calibrations and DIF detection

Using the two-group IRT-based DIF models, seven out of the 109 items (three from Positive Emotional and Sensory Expectancies, three from Health Expectancies, one from Social Motivations) were flagged as exhibiting DIF based on the wABC values > 0.4 criterion. Table 2 lists these items with their Spanish (in normal type) and English (in italics) parameter estimates. In general, the slope parameters do not appear to be very different across the two language groups, although items 4 (“smoking causes me to get tired easily”) and 7 (“if I quit smoking I will be less welcome around my friends who smoke”) have notably stronger slopes for the Spanish sample relative to the English. With respect to location parameters, DIF items 1, 2, and 5 have location parameters that are higher for Spanish relative to English-speakers indicating that Spanish speakers are less likely than expected to endorse these items, producing lower scores than expected. In contrast, the other four DIF items have lower location parameters for the Spanish speakers indicating they are more likely than expected to endorse these items producing higher scores than expected. To illustrate the typical magnitude of an item exhibiting DIF in this direction, Figure 1 presents the expected score curves for the focal group (solid, Spanish) and the reference group (dotted, English) for the Social Motivation bank DIF item: “If I quit smoking, I will be less welcome around my friends who smoke.” The x-axe uses the standard PROMIS T-score scale with mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. The non-overlapping curves illustrate that Spanish-speakers score higher than expected relative to English-speakers given the underlying group difference. The size of DIF for this item is quantified by a wABC value of 0.51, which is reflected by the area between the curves.

Table 2.

Spanish (Normal Type) and English (Italics) Parameter Estimates for Items Showing DIF According to Language

| Domain | Item | wABC | a | b 1 | b 2 | b 3 | b 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Emotional and Sensory Expectancies | 1. When I stop what I’m doing to have a cigarette it feels like “my time.” | 0.62 | 1.96 (0.14) | −0.94 (0.11) | −0.20 (0.07) | 0.79 (0.08) | 1.98 (0.14) |

| 1.63 (0.06) | −1.73 (0.07) | −0.79 (0.04) | 0.16 (0.04) | 1.00 (0.05) | |||

| 2. Smoking is relaxing. | 0.83 | 2.09 (0.14) | −1.56 (0.15) | −0.50 (0.08) | 0.46 (0.07) | 1.57 (0.11) | |

| 2.07 (0.08) | −2.83 (0.11) | −1.55 (0.05) | −0.5 (0.03) | 0.55 (0.04) | |||

| 3. I enjoy the sensations of a long, slow exhalation of smoke. | 0.47 | 1.57 (0.13) | −2.74 (0.28) | −1.25 (0.15) | 0.14 (0.08) | 1.34 (0.12) | |

| 1.84 (0.06) | −1.31 (0.05) | −0.42 (0.04) | 0.57 (0.04) | 1.50 (0.05) | |||

| Negative Health Expectancies | 4. Smoking causes me to get tired easily. | 0.43 | 2.31(0.16) | −0.46 (0.07) | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.80 (0.08) | 1.57 (0.12) |

| 1.69 (0.07) | −0.12 (0.04) | 0.63 (0.04) | 1.52 (0.07) | 2.11 (0.09) | |||

| 5. If I quit smoking I will breathe easier. | 0.43 | 2.32 (0.19) | −1.43 (0.15) | −0.72 (0.10) | 0.08 (0.07) | 0.90 (0.08) | |

| 2.60 (0.10) | −1.89 (0.06) | −1.04 (0.04) | −0.28 (0.03) | 0.34 (0.03) | |||

| 6. Smoking gives me a headache. | 0.44 | 1.18 (0.13) | 0.44 (0.11) | 1.16 (0.14) | 2.22 (0.23) | 3.24 (0.34) | |

| 1.08 (0.08) | 1.39 (0.09) | 2.49 (0.15) | 3.76 (0.23) | 4.69 (0.32) | |||

| Social Motivations | 7. If I quit smoking I will be less welcome around my friends who smoke. | 0.51 | 1.24 (0.12) | 0.40 (0.10) | 0.94 (0.12) | 1.87 (0.18) | 3.30 (0.31) |

| 0.88 (0.08) | 1.85 (0.14) | 2.67 (0.20) | 4.04 (0.30) | 5.02 (0.38) |

DIF = Differential Item Functioning; wABC = weighted Area Between the expected score Curve. Spanish-language parameters are in normal type and English-language parameters are in italics. Standard errors for parameter estimates are in parentheses.

Figure 1.

Item #7 from the Social Motivation bank showing weighted Area Between the expected score Curves (wABC) to quantify Differential Item Functioning (DIF). Note: Larger area between the two curves represents higher wABC values. We identified a total of seven items from three domains with wABC > 0.4 as DIF items.

Spanish Item Bank Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 displays descriptive information for the Spanish items banks compared to the English. As can be seen, all bank means are higher for the Spanish sample compared to the English sample; standard deviations for the Spanish sample also tended to be slightly higher. With respect to reliability, the full bank and SF score reliabilities for the Spanish translation are comparable to the English. Correlations among full bank scores and correlations of the bank scores with the measures of smoking quantity, quitting interest and recent quitting attempt are also displayed in Table 3. The pattern of interbank correlations for the Spanish translation is similar to that observed for the English version.27 With the exception of the correlation between health expectancies and emotional and sensory expectancies (r = 0.06), all correlations among item banks were significant at P < .01. The inter-bank correlations ranged in magnitude from 0.06 to 0.88. Associations among coping expectancies, emotional and sensory expectancies, and social motivations are strong as are the correlations between the two negative expectancies (ie, health and psychosocial). Although nicotine dependence scores were relatively highly correlated with scores from all other banks, the coping expectancies bank scores were most strongly associated with nicotine dependence.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for the Spanish (Normal Type) and English (Italics) Item Banks Including Mean (SD), SF Score Reliability, Correlations Among Bank Score and With Other Smoking Measures

| Nicotine Dependence | Coping Expectancies | Emotional and Sensory Expectancies | Health Expectancies | Psychosocial Expectancies | Social Motivations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bank mean (SD) | 51.9 (11.2) | 51.3 (11.1) | 56.5 (12.9) | 55.3 (10) | 54.0 (11.7) | 55.6 (12.1) |

| 50.0 (10) | 50.0 (10) | 50.0 (10) | 50.0 (10) | 50.0 (10) | 50.0 (10) | |

| Bank score reliability | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.92 |

| 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.90 | |

| SF score reliability | 4-item: 0.77, 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.77 |

| 8-item: 0.88, 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.80 | |

| Coping Expectancies | 0.88 | |||||

| 0.73 | ||||||

| Emotional and Sensory Expectancies | 0.84 | 0.88 | ||||

| 0.51 | 0.70 | |||||

| Health Expectancies | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.06 | |||

| 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.04 | ||||

| Psychosocial Expectancies | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.77 | ||

| 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.80 | |||

| Social Motivations | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.18 | 0.39 | |

| 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.28 | 0.31 | ||

| Smoking Quantity | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.17 | |

| Quitting Interest | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.18 | 0.34 | 0.26 | −0.16 |

| 0.25 | 0.13 | −0.09 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.08 | |

| Recent Quitting Attempt | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.07 |

| 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.22 | −0.23 | −0.03 |

SF = short form. Quitting interest high score = more interested; recency of last quit attempt high score = less recent. All correlations in bold are significant at P < .01.

As also shown in Table 3, the magnitude and pattern of Spanish item bank correlations with smoking and quitting items generally follow that found in the English sample, providing preliminary evidence for validity of the use of the Spanish banks. Nicotine dependence is most strongly correlated with smoking quantity (r = 0.31, P < .01), interest in quitting is mostly related to negative health expectancies (r = 0.34, P < .01) and psychosocial expectancies (r = 0.26, P < .01). However, contrary to those observed in the English sample, recency of quitting is not significantly correlated with any of the Spanish bank scores.

Discussion

Developing a Spanish version of the PROMIS smoking toolkit is important and timely given that the size of the Spanish-speaking population in the world is surpassing that of the English-speaking population. We calibrated the Spanish version of the PROMIS smoking item banks using a sample of Spanish-speaking Hispanic daily adult smokers and an English-speaking subsample from the original calibration study of the PROMIS daily smoking item banks. The Spanish and English (daily smoker) item banks include the same items, but the Spanish item parameters are updated for a small number of items (seven out of 109) that exhibited DIF between languages, while retaining the original item parameters for the rest of the items. These new item banks can be used in future data collection efforts in either fixed form or CATs. We also provide updated summed score to scaled score translation tables for the Spanish SFs.

In this study, we focused on language DIF because other conditioning variables (eg, gender, age and, ethnicity) have been addressed previously in the English item bank construction.8 We also focused on the use of wABC as a practical effect size measure to quantify DIF. This mitigates the problems associated with using null hypothesis significance testing for DIF analysis, which may be overly sensitive when used with large samples. The current study is not without limitations. For example, the cross-sectional calibration sample does not offer an opportunity for us to investigate prospective validity of scores from the assessment instruments. Further, although the Spanish-speaking sample was selected to represent Spanish-speaking smokers in the United States with respect to gender and age, they may not be entirely representative as they were recruited from an internet panel.

Future Directions

PROMIS measures are changing the landscape of patient reported outcomes measurement. As an NIH Roadmap initiative, PROMIS was developed, in part, to increase the availability and use of a common set of standardized assessment tools that in the long term would enhance the comparability of findings across studies examining patient-reported constructs, reduce respondent burden, and increase measurement precision.28 Although the PROMIS development efforts have always started with the English language, researchers have been working on translation and recalibration of the PROMIS tools into different languages in order to benefit broader populations. With this study, the PROMIS smoking item banks join the ranks of a multitude of other PROMIS banks that have been translated into Spanish (http://nihpromis.org/measures/translations). When used in other Spanish-speaking countries, minor revisions using local words can be applied to fit the regional culture, but are not supposed to change the meaning or content of the items. In addition to validating the translated bank scores in future studies of Spanish-speaking smokers, it may be fruitful to translate the smoking item banks into other languages such as Chinese, following the trend of the larger PROMIS effort to maximize the usefulness of these robust measurement tools (eg, Chinese translation of pediatric anxiety and depression SFs29).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material can be found online at http://www.ntr.oxfordjournals.org

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA026943).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Edelen MO, Tucker JS, Shadel WG, Stucky BD, Cai L. Toward a more systematic assessment of smoking: development of a smoking module for PROMIS®. Addict Behav. 2012;37(11):1278–1284. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shadel WG, Tucker JS, Edelen MO, Stucky BD, Hansen M, Cai L. Development of the PROMIS Nicotine Dependence item bank. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(suppl 3):S190–S201. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shadel WG, Edelen MO, Tucker JS, Stucky BD, Hansen M, Cai L. Development of the PROMIS Coping Expectancies of Smoking item bank. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(suppl 3):S202–S212. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tucker JS, Shadel WG, Edelen MO, et al. Development of the PROMIS® Positive Emotional and Sensory Expectancies of Smoking Item Banks. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(suppl 3):S212–S222. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntt281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edelen MO, Tucker JS, Shadel WG, et al. Development of the PROMIS® Health Expectancies item banks. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(suppl 3):S223–S231. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stucky BD, Edelen MO, Tucker JS, et al. Development of the PROMIS® Negative Psychosocial Expectancies of Smoking item banks Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(suppl 3):S232–S240. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntt282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tucker JS, Shadel WG, Edelen MO, et al. Development of the PROMIS® Social Motivations for Smoking Item Banks. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(suppl 3):S241–S249. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntt283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hansen M, Cai L, Stucky BD, Tucker JS, Shadel WG, Edelen MO. Methodology for developing and evaluating the PROMIS® smoking item banks. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(suppl 3):S175–S189. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntt123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stucky BD, Huang W, Edelen MO. The psychometric performance of the PROMIS Smoking Assessment Toolkit: comparisons of real-data CATs, short forms, and mode of administration [published online ahead of print April 8, 2015]. Nicotine Tob Res. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2014:P25–1143. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(47):1108–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krogstad JM, Stepler R, Lopez MH. English Proficiency on the Rise Among Latinos: U.S. Born Driving Language Changes. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paul LM, Simons GF, Fennig CD. Ethnologue: Language of the World, Eighteenth Edition Dallas, TX: SIL International; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paz SH, Spritzer KL, Morales LS, Hays RD. Evaluation of the patient reported outcomes information system (PROMIS®) Spanish-language physical functioning items. Qual Life Res. 2012;22(7):1819–1830. doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0292-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bock BC, Niaur RS, Neighbors CJ, Carmona-Barros R, Azam M. Differences between Latino and non-Latino White smokers in cognitive and behavioral characteristics relevant to smoking cessation. Addict Behav.2005;30(4):711–724. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edelen MO. The PROMIS® smoking assessment toolkit-background and introduction to supplement. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(suppl 3):S170–174. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cella D, Hernandez L, Bonomi AE, et al. Spanish language translation and initial validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy quality-of-life instrument. Med Care. 1998;36(9):1407–1418. doi:10.1097/00005650-199809000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cai L, du Toit SHC, Thissen D. IRTPRO: Flexible, Multidimensional, Multiple Categorical IRT Modeling [Computer Software]. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, eds. Testing Structural Equation Models. London, United Kingdom: Sage Ltd; 1993:136–162. [Google Scholar]

- 20. MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods. 1996;1(2):130–149. doi:10.1037//1082-989X.1.2.130. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Edelen MO, Stucky BD, Chandra A. Quantifying ‘Problematic’ DIF within an IRT Framework: Application to a Cancer Stigma Index. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(1):95–103. doi:10.1007/s11136-013-0540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. www.R-project.org/ Accessed October 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Steinberg L, Thissen D. Using effect sizes for research reporting: examples using item response theory to analyze differential item functioning. Psychol Methods. 2006;11(4):402–415. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.11.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Edelen MO, Thissen D, Teresi JA, Kleinman M, Ocepek-Welikson K. Identification of differential item functioning using item response theory and the likelihood-based model comparison approach: application to the Mini-Mental State Examination. Med Care. 2006;44(11)(suppl 3):S134–142. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000245251.83359.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med Care. 2007;45(suppl 1):S22–S31. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Edelen MO, Stucky BD, Hansen M, Tucker JS, Shadel WG, Cai L. The PROMIS® smoking initiative: initial validity evidence for six new smoking item banks. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(suppl 3):S250–S260. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Edelen MO. The PROMIS® smoking assessment toolkit – background and introduction to supplement. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(suppl 3):S170–S174. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu Y, Wang J, Hinds PS, et al. The emotional distress of children with cancer in China: an item response analysis of C-Ped-PROMIS Anxiety and Depression short forms. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(6):1491–1501. doi:10.1007/s11136-014-0870-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.