Abstract

Molecular self-assembly, a phenomenon widely observed in nature, has been exploited through organic molecules, proteins, DNA and peptides to study complex biological systems. These self-assembly systems may also be used in understanding the molecular and structural biology which can inspire the design and synthesis of increasingly complex biomaterials. Specifically, use of these building blocks to investigate protein folding and misfolding has been of particular value since it can provide tremendous insights into peptide aggregation related to a variety of protein misfolding diseases, or amyloid diseases (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, type-II diabetes). Herein, the self-assembly of TK9, a 9 residue peptide of the extra membrane C-terminal tail of the SARS Corona virus envelope, and its variants were characterized through biophysical, spectroscopic and simulated studies, and it was confirmed that the structure of these peptides influence their aggregation propensity, hence, mimicking amyloid proteins. TK9, which forms a beta-sheet rich fibril, contains a key sequence motif that may be critical for beta-sheet formation, thus making it an interesting system to study amyloid fibrillation. TK9 aggregates were further examined through simulations to evaluate the possible intra- and inter peptide interactions at the molecular level. These self-assembly peptides can also serve as amyloid inhibitors through hydrophobic and electrophilic recognition interactions. Our results show that TK9 inhibits the fibrillation of hIAPP, a 37 amino acid peptide implicated in the pathology of type-II diabetes. Thus, biophysical and NMR experimental results have revealed a molecular level understanding of peptide folding events, as well as the inhibition of amyloid-protein aggregation are reported.

INTRODUCTION

The formation of nanostructures through molecular self-assembly has been demonstrated to be a ubiquitous process in nature as seen by organic molecules (polymers), proteins, peptides and DNA. These nanostructures have been characterized by their highly ordered aggregate formation through non-covalent interactions (e.g., electrostatic, hydrogen bonds, van der Waals, and aromatic π-stacking and cation-π). The emerging field of nanotechnology has exploited self-assembly systems due to the key advantage that their physical, chemical, optoelectronic, magnetic and mechanical properties are tunable via control of their size and shape.1 Interestingly, all the aforementioned non-covalent forces are quite weak in nature, individually, but cumulatively they support the self-organization of simple units into complicated and controlled structures.2 Despite tremendous research efforts, the relative involvement of these forces in self-assembly processes is yet to be more clearly understood. Recently, substantial attention has been intended for the rational design and structural analysis of peptide based self-assembly due to their widespread diversity in chemical, structural and functional aspects.1,3 Furthermore, the complex nature of biomolecules limits the comprehensive understanding of the factors controlling the self-assembling properties. To examine this in more detail, short peptides or peptide fragments can be constructed relatively quickly and may serve as the competent building blocks for self-assembled systems thus avoiding the complexities of forming and studying large protein structures. .

Self-assembled peptide systems have also been utilized in studying protein-folding events in order to provide insight into the thermodynamic properties of protein folding and misfolding. These investigations have also helped gain information about specific structural motifs adopted by specific amino acid sequences and combinations which may be responsible for protein misfolding and amyloid formation. Therefore, studying the self-assembly of peptides has been utilized as an important tool for analyzing the local structure (e.g., secondary structure) of peptide fragments in the context of the global protein structure.4 These peptide nanostructures are generally formed from beta (β)-sheet motifs, although a few helical-based assemblies have also been reported.5,6 Based on various structural, chemical and physical properties they are classified according to the following categories: a) lipid-like peptides, b) surfactant peptides, c) amphiphilic peptides, d) aromatic di-peptide motifs, e) cyclodextrin-based polyionic amino acids from known self assembled protein, e) cyclic peptides and f) arbitrarily chosen peptide sequence based on amino acid properties.7 The unique supramolecular assemblies can be readily tuned by modifying structural properties such as changing the amino acid sequence or conjugating chemical groups or by varying experimental parameters such as pH or solvent. Peptide nanostructures have also been utilized in vast miscellaneous fields, from antibacterial agents to molecular electronics with a great achievement and therefore have become of great interest to study.8, 9

Importantly, investigating self-assembly systems at the molecular level have been of particular value in studying the complex phenomena behind the aggregation of amyloid proteins and aggregation of other proteins related to fatal protein conformational disorders.10 It has been found that amyloid-related diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Prion diseases, Type II diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease) are connected by the aggregation of relatively unstructured monomers into a β-sheet rich fibrillar aggregates.11,12 In spite of the diversity in sequence homology, the fibrillar network have similar morphologies; however, the precise biochemical/biophysical pathways and mechanism of protein fibrillation still remain elusive. Self-assembled short peptides have the potential to serve as model systems to studying amyloid aggregation by simplifying the study of amyloidosis as seen in a study by Lynn and co-workers.13 This can help probe specific protein-protein interactions between the small peptide assemblies and translate this information to elucidating the aggregation properties of the native peptide/protein. Furthermore, small peptide fragments from amyloid proteins (KLVFF in amyloid-β and NFGAIL in hIAPP) have demonstrated to have inhibitory properties, thus modifying or in some cases halting the aggregation pathway. Therefore, studying self-assembled peptide fragments may also help potentially uncover possible motifs that may be utilized for amyloid inhibition and eventually therapeutic applications.

In the present study, we have investigated and analyzed the self assembly of a 9 residue peptide (hereafter denoted as TK9) and its derivatives taken from the sequence of the carboxyl terminal (55-63) of SARS Corona Virus Envelope protein (Scheme 1).14 Generally, corona viruses are enveloped and this enveloped (E) region may be the main culprit in causing virulence related to various respiratory diseases such as, common colds, bronchiolitis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans and other.15 The E regions are peptide fragments consisting of 76-108 amino acids and composed of a flexible region at both N- and C- terminals and α-helical transmembrane (TM) region.16 This region has shown to adopt mainly helical structure in the presence of SDS micelles, suggesting that a membrane surface may influence its secondary structure.16 Upon mutation of the 56VYVY59 region of the C-terminal tail in the SARS Corona virus, the secondary structure has changed to a more discrete β-structure.16

Scheme 1.

(A) SARS CoV-E sequence with TK9 region shown in blue. (B) The three-dimensional solution structure of SARS CoV-E protein in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) micelle (2MM4.pdb). The C-terminal tail, Thr55 – Lys 63 adopted alpha helical conformation in micelle, makerd by circle, used in this study. (C) The primary sequence of C-terminal tail, TK9 or its shorter fragments.

To gain further insight, whether the short peptide, TK9 and its variants have a self-assembling tendency, we carried out detailed biophysical and high resolution analyses of TK9. These data demonstrated that TK9 self assembles and forms a β-sheet secondary structure in solution. To support our experimental findings and also to extract out the atomic level interactions acting as a driving force for this self-assembly process we performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Furthermore, we also studied the ability of TK9 to inhibit the aggregation of a 37-residue human islet amyloid polypeptide protein (hIAPP) in order to obtain possible structural motifs that may be beneficial for the mitigation of hIAPP aggregation. Previous studies have shown that unstructured hIAPP monomers aggregate to form toxic intermediates and amyloid fibers that composed of β-sheet peptide structures that are implicated in type II diabetes. Therefore, there is considerable current interest in developing compounds to inhibit hIAPP aggregation and islet cell toxicity. In this context, the amyloid-inhibiting ability of TK9 could be useful and aid in the development of potent amyloid inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and preparation of stock solutions

The parent peptide, TK9 and its shorter fragments (Scheme 1) were synthesized on a solid phase peptide synthesizer (Aapptec Endeavor 90) using Fmoc protected amino acids and Rink Amide MBHA resin (substitution 0.69 mmol/g; Novabiochem, San Diego, California) by following a solid phase peptide synthesis protocol described elsewhere.17,18 All the crude peptides were further purified by reverse phase HPLC (SHIMADZU, Japan) using a Phenomenix C18 column (dimension 250 × 10 mm, pore size 100 Å, 5-μm particle size) by linear gradient elution technique using Water and Methanol as solvent both containing 0.1% TFA as the ion pairing agent. The purity and molecular weight of the eluted peptides were confirmed by MALDI-TOF (Bruker, Germany). 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS) and deuterium oxide (D2O) were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Tewksbury, MA). Thioflavin T dye was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Throughout the experiment HPLC grade water was used for sample preparation. hIAPP was purchased from Genscript (Piscataway, NJ). hIAPP was prepared by dissolving the peptide in hexafluoroisopropanol (Sigma Aldrich) followed by lyophilization. Peptide stock was dissolved in 100 μM HCl (pH 4), sonicated for 1 min, diluted into the appropriate buffer system and kept on ice until use.

Circular dichroism

All circular dichroism experiments were performed on Jasco J-815 spectrometer (Jasco International Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan) furnished with a Peltier cell holder and temperature controller CDF-426L at 25 °C. The peptide concentrations were 25 μM for all CD measurements. The samples were scanned between 190 to 260 nm wavelength at a scanning speed of 100 nm min−1. The data interval was 1 nm and path length 2.0 mm. All data-points are the resultant of an average of 4 repetitive scans. All experiments were performed in 10 mM phosphate buffer of pH 7.0. Each spectrum was baseline corrected with reference to buffer. The data obtained in mill degrees were converted to molar ellipticity (ME) (deg.cm2.dmol−1) and plotted against wavelength (nm).

Fluorescence assays

Tyrosine fluorescence experiments were performed using Hitachi F-7000 FL spectrometer with a 0.1 cm path length quartz cuvette at 25 °C. Intrinsic tyrosine fluorescence property was used to monitor the self assembly property for tyrosine containing peptides TK9, TY5, YR5 using an excitation wavelength of 274 nm and emission in a range of 290-370 nm.19 The excitation and emission slit both were 5 nm. The peptide concentrations were 25 μM throughout the experiment. Thioflavin-T (ThT) experiments were performed on a BioTek multiplate reader using an excitation wavelength of 440 nm and emission wavelength of 485 nm. Samples were prepared by adding hIAPP (10 μM) to a buffer solution (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) containing ThT (20 μM) and varying concentrations of TK9 monomer (0.5 – 2 equiv). TK9 aggregates for the ThT assay were prepared by incubation at 37 °C for 7 days.

Dynamic light scattering

DLS experiments were performed using Malvern Zetasizer Nano S (Malvern Instruments, UK) equipped with a 4-mW He-Ne gas laser (beam wavelength = 632.8 nm) and 173° back scattering measurement facility. All samples were filtered using 0.25-μm filter paper (Whatman Inc, NJ) and degassed before use and measured at 298 K using a low volume disposable sizing cuvette. The peptide concentration was kept at 10 μM in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) during the duration of the experiment.

Nuclear magnetic resonance

The synthetic peptide, TK9 and its analogues were dissolved in milli-Q water (pH 7.0). All NMR spectra were recorded at 298 K using Bruker Avance III 500 MHz NMR spectrometer, equipped with a 5 mm SMART probe. Two-dimensional total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) and rotating frame nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY) spectra of TK9 were acquired in water containing 10% D2O and DSS (2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane 5-sulfonate sodium salt) as an internal standard (0.0 ppm for methyl protons). The peptide concentration was kept at 1 mM for the sequential assignment and relaxation studies, respectively. TOCSY mixing time was set to 80 ms using the MLEV-17 spin-lock sequence to ensure coherence transfer via scalar couplings, whereas a 150 ms spin-lock mixing time was used for ROESY experiments. The TOCSY and ROESY experiments were performed with 456 t1 increments and 2048 t2 data points. The residual water signal was suppressed by excitation sculpting techniques. The spectral widths were set to 10 ppm in both dimensions with a saturation delay of 1.5 sec. Data acquisition and data processing were carried out using Topspin™ v3.1 software (Bruker Biospin, Switzerland).

The two-dimensional NMR data were assigned and analyzed using SPARKY20 program. The cross peak intensities measured from ROESY spectra were qualitatively classified as strong, medium, and weak, which were then converted to upper bound distance limits of 3.0, 4.0, and 5.5 Å, respectively. The lower bound distance was constrained to 2.0 Å to avoid van der Waals repulsion. The backbone dihedral angle (phi, ϕ) was varied from −30° to −120° to restrict the conformational space for all residues. Finally, Cyana 2.1 software was used for structure calculation with the help of distance and dihedral angle restraints.21 Several rounds of refinement were performed based on the NOE violations, and the distance constraints were accustomed accordingly. A total of 100 structures were calculated, and 20 conformers with the lowest energy values were selected to present the NMR ensemble and staring structure for coarse grain molecular dynamics simulation.

A series of one-dimensional proton NMR spectra for TK9 and its analogues were recorded at different time intervals to determine their aggregation tendency. The spectra were acquired with water suppression with a spectral width of 12 ppm, 128 transients, a relaxation delay of 1.5 sec. The spectra were processed and plotted with TopSpin software (Bruker, Switzerland) using a line broadening of 1.0 Hz.

Saturation transfer difference (STD) NMR experiments for a sample containing TK9 (0.5 mM) and hIAPP monomers (10 μM) were carried at 25 °C for 12 hours consecutively with an interval of 15 min using a Bruker 600 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a cryo probe. The peptide, hIAPP or its fibril was irradiated at −1 (on-resonance) and at 40 ppm (off-resonance) for a duration of 2 s and 128 scans were co-added to get the spectrum. The selective irradiation was achieved by a train of Gaussian pulses with 1% truncation for a duration of 49 ms with an interval of 1 ms at 50 dB.

Relaxation studies

To gain access the atomic level dynamics present one-dimensional spin-spin (T1) and spin-lattice (T2) relaxation experiments for TK9 were performed using 500 MHz Bruker Avance III NMR spectrometer. T1 experiments were performed using the same protocol that we published earlier with different inversion recovery delays starting from 50 ms to 5 s.22 Similarly, T2 measurements were carried out using the CPMG sequence for a set of delays: 2, 6, 32, 100, 200, 400, 800, 2000, 3000 and 4000 ms.23

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The incubated peptide solutions were deposited on a glass slide (1 cm2) and dried oven night in air. The slide was then coated with gold for 120 s at 10 kV voltage and 10 mA current. The samples were viewed on a ZEISS EVO-MA 10 scanning electron microscope equipped with a tungsten filament gun operating at 10 kV.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The 500 μM peptide stock solutions were incubated at room temperature for up to 15 days and 10 μL aliquots of the solution were placed on 300 mesh Formvar/carbon coated copper TEM grids (Ted Pella, Redding, CA 96049, USA). It was allowed to adsorb on TEM grid for about 3-4 minutes and excess volume was removed with filter paper. The grid was negatively stained with 5 % (v/v) freshly prepared uranyl acetate in water. After 5 minute excess dye was removed and the grids were viewed on a JEOL JEM 2100 HR TEM microscope operating at 80 kV. A set of TEM samples for TK9 were also viewed on a Philips Model CM-100 transmission electron microscope (80 kV, 25,000× magnification) Digital images were acquired using Gatan Digital Micrograph 2.3.0 image Capture Software.

Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Coarse-Grained (CG) molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of TK9 was performed using Martini model.24,25 Using this model, TK9 is mimicked by 24 beads in a single chain, as shown in Figure S1. Simulation systems were built with 20 chains of beaded TK9 placed randomly in a box of size 12 nm. Energy minimization was initially conducted on peptide in a vacuum using the steepest descent method with a maximum step size of 0.01 nm and a force tolerance of 10 kJ mol−1 nm−1. Solvation of the system was carried out with 59652 CG water molecules (each CG water molecule corresponds to 4 all atom water molecules). The solvated system was further minimized using the same parameters as that of energy minimization in a vacuum. Then MD simulation was performed using NPT. The velocities were assigned according to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at 320 K. Temperature was kept at 310 K by the Berendsen method with a time constant of 0.3 ps, and the pressure was maintained at 1 bar with a time constant of 3 ps and a compressibility of 3×10−5 bar−1. The periodic boundary conditions (PBC) were applied. The non-bonded Lennard-Jones (LJ) and electrostatic interactions were calculated using a cut off of 1.2 nm. Furthermore, the standard shift function in GROMACS was used to reduce undesired noise.26 Specifically, the LJ potential and electrostatic potentials were shifted to zero from 0.9 and 0.0 nm, respectively, to the cut off distance (1.2 nm). A time step of 30 fs was used and trajectory was saved every 150 ps for analysis. The simulation duration was 1 μs. Structural changes in the assembly during the simulation run are captured at different time step as shown in Figure S2.

Reverse construction of all atom system

Reconstruction of all atom (AA) system from CG was carried out to regain the atomic details. At first, AA particles were placed near to the corresponding CG beads and coupled to CG beads by harmonic restraints. This restrained the system further and then was processed by simulated annealing (SA); the final relaxed atomic model was obtained by the gradual removal of the restraints.27

There construction simulations started from the snapshot at 999 ns time step of the CG simulations as illustrated in Figure S3. The atomistic simulations were carried out with a 2-fs integration time step, and the temperature was controlled by coupling to a Nosé–Hoover thermostat with a time constant of 0.1 ps.28 Because of the random initial placement of the atomistic particles, no constraints were applied in the reconstruction simulations, except for SPC water.

For the simulations of the TK9, the 53 a6 parameter set of the GROMOS united atom force field was used.29 The system was simulated within periodic boundary conditions. Non-bonded interactions were calculated using a triple-range cut off scheme: interactions within 0.9 nm were calculated at every time step from a pair list, which was updated every 20 fs. At this time steps, interactions between 0.9 and 1.5 nm were also calculated and kept constant between updates. A reaction-field contribution was added to the electrostatic interactions beyond this long-range cut off, with Єr=62. In the simulations of bulk SPC water, at win range cut off scheme was used, with a single cut off at 0.9 nm and a pair list up dated every 20 fs. Here, along-range dispersion correction was applied in addition to the reaction field. Other simulation parameters are as given in Table S1.

RESULTS

Design considerations for TK9 and its variants

The SARS-CoV Envelope region (Cov E) (Scheme 1a) contains a relatively hydrophobic C-terminal region (Scheme 1B), composed of an alpha helix (α-helix) at the trans-membrane followed by a β-structured region,55TVYVYSRVK63, or TK9, which has been considered an essential sequence content for its function. This region has been predicted to be responsible for directing the protein to the Golgi region.16,30,31 It should be mentioned that this type of motif remains conserved in other corona viruses and is abundantly expressed in infected cells and may also be critically involved in viral protein assembly.32,33 Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy investigations have also shown that this portion of the protein can intrinsically adopt both a random coil and β-sheet conformation in the absence of a membrane environment.30 The folding domain (β-structured region), which contains the sequence of TVYVYSRVK and its fragments (Scheme 1B) contain residues and sequences similar to those of amyloid proteins. This has led to the hypothesis that TK9 may have similar properties to the folding domains of amyloid proteins (e.g., amyloid-β), where certain residue regions have limited water solubility and adopt a β-sheet structure and may aggregate to form amyloid-like fibrillar species. This observation has made TK9 and its derivatives insightful nanostructure systems to study protein assembly and mechanism of folding.34 Specifically, residues I46 – V62 contain branched and bulky side chains which may favor the formation of β-sheet structures.35 The first five resides of TK9 and TY5 (TVYVY) (Scheme 1C) also contain a peptide motif demonstrated to form amyloid-like fibrils; therefore, this short peptide fragment and its derivatives namely, TY5, YR5 and SK4 (Scheme 1C) were chosen as model systems to give possible insights into amyloid folding events.

TK9 and TY5 are more prone to aggregation with increased incubation time

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) is an analytical method used to establish the size distribution of an ensemble of particles from Brownian motion property in solution.36 Here, we employed DLS to access the size distribution of the supramolecular structures formed during different incubation periods. It is seen that freshly prepared TK9 or its analogues, TY5, YR5 and SK4 (Scheme 1C) show a narrow size distribution pattern with a hydrodynamic diameter of ~ 27 nm (Figure 1A and Figure S4). The narrow distribution confirms that the peptides are monomer in freshly dissolved solution at early time points. However, with increasing the incubation time period for TK9, TY5 and YR5, the size distribution profile became wider, which accounts for the presence of polymeric subunits in solution (Figure S4). After 15-days of incubation, clear distinction in the hydrodynamic diameters were observed for the peptides. TK9 and TY5 showed the highest change in hydrodynamic diameter, whereas YR5 showed a moderate change in size distribution only after 25 days of incubation (Figure S4). On the other hand, SK4 showed a negligible amount of change in hydrodynamic diameter within a period of 25 days of incubation, which suggests its lower aggregating propensity. This trend pointed out that aromatic amino acids (Tyr) of these peptides may contribute significantly to the shape and size of their nanostructure assemblies and that polar amino acids may not directly influence their size. Overall, our DLS results proved a similar aggregation behavior of the parent peptide TK9 and its N-terminal fragments TY5 and YR5 can be seen after 25 days of incubation.

Figure 1.

(A) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) plot for TK9 (red), TY5 (blue), YR5 (green) and SK4 (pink);the intensity vs. size distribution bar diagram are plotted at different time intervals. (B – E) Circular Dichroism (CD) plots of secondary structure of TK9 and its fragments measured after freshly preparation and incubation with 15 days.

Furthermore, circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was used to monitor the secondary structure of the peptide fragments at different incubation time (Figure 1B-E). Freshly prepared TK9 and its truncated shorter fragments showed a strong negative maximum at ~195 nm, characteristic of random coil conformation of the peptides or proteins (Figure 1B-E). Interestingly, after 15 days of incubation, samples containing TK9 and TY5 showed distinct β-sheet type CD spectral signature consisting of positive maximum at 200 nm and a negative maximum at 215 nm due to n - π* and π - π* transition (Figure 1B and 1C). In contrary, the CD spectrum of YR5 showed two peaks, one at ~ 198 nm and another broad peak at ~ 215 nm (Figure 1D). Similarly, SK4 showed a large broadening of peaks (Figure 1E). This result clearly signifies that both YR5 and SK4 are highly dynamic in nature and there may be conformational exchange between random coils to β-sheet in a dynamic state (Figure 1D-E). Overall the CD data identified that TK9 and TY5 undergo structural reorganization from random coil to β-sheet over time while the other fragments are not prone to this similar conformational change.

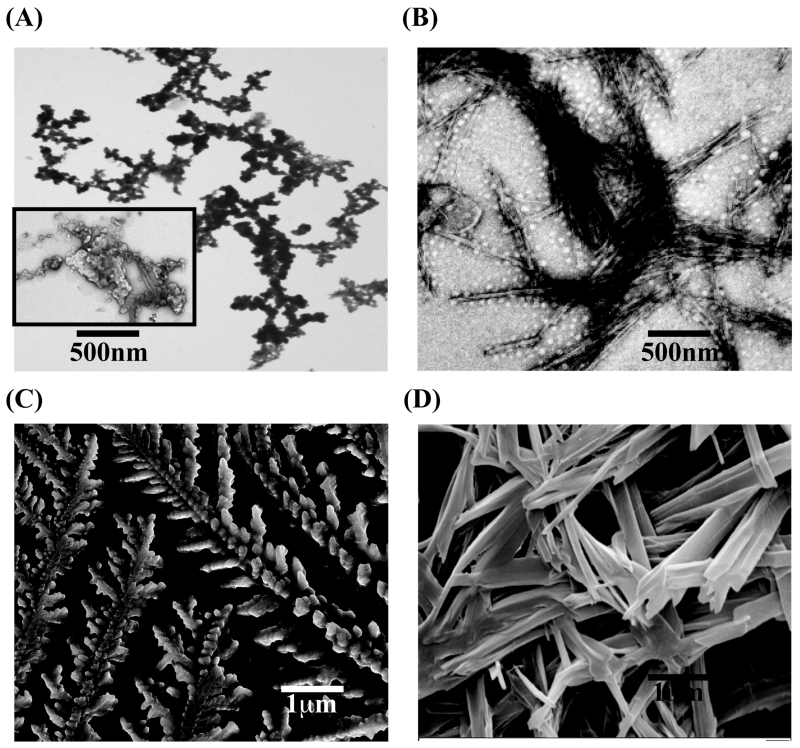

Morphology of TK9 and its variants

To understand further about the morphological change of the nanostructures of the peptide self-assembly, various electron microscopic techniques such as transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were employed. TEM data revealed that freshly prepared TK9 did not show any measureable structure (data not shown), which is in very good agreement with the CD data (Figure 1B). However, TEM analysis of the sample containing TK9 alone with 10 days of incubation displayed a dense fibrillar network which has slight amorphousity and unbranched characteristics (Figure 2A and inset, respectively), suggesting that the peptide region are able to form β-sheet morphology, which could be in good agreement with the TEM images of β-sheet forming amyloid fibrils originated from either Aβ or hIAPP.37 This structure also emphasized that the rate of nucleation for the β-sheet formation could be slower due to presence of two positive charge residues, Arg7 and Lys9 at the C-terminal of the peptide sequence. However, the effect of fibrillation was more pronounced in case of TY5 peptide sequence consisting beta branched amino acids such as Thr1-Val2-Tyr3-Val4-Tyr5 residues. In addition, these residues may be more prone to form a plane of β-sheet structures (Figure 2B). Hence, TY5 showed distinct nano-rod type of morphology (Figure 2B) after 25 days of static incubation at 37 °C. In contrast, YR5 and SK4 did not show any defined nanostructure by TEM (data not shown), which could be attributed to the sole presence of charged residues at the C-terminal of TK9 sequence which did not allows the peptides to self assemble.

Figure 2.

Transmission and scanning electron micrographs showing fibrillar nanostructure morphology for TK9 (A and C) and TY5 (B and D), respectively.

Subsequently, SEM experiments were performed to understand the self-assembly propensity of TK9 and its analogues after incubation at 37 °C for several days (Figure 2 C-D). TK9 exhibited well-defined, branched, long rod-like fibers (Figure 2C) after 25 days. The truncated analogue, TY5 showed a dense nano-tubular architecture (Figure 2D). These results indicate that both TK9 and TY5 form well-packed molecular fibrils in solution. In contrary, the central region of the peptide sequence, YR5 showed an amorphous like architecture rather than uniformly well-defined fibers and tubes (Figure S5). The C-terminal truncated peptide, SK4 consists of the charged residues (Ser6, Arg7 and Lys9) did not allow the peptide to adopt any particular structure (Figure S5). Taken together, TK9 and TY5 self assembled to adopt a well defined nanostructure confirmed by both TEM and SEM.

Fluorescence measurements to monitor peptide aggregation

The intrinsic fluorescence property of tyrosine (Tyr) for TK9, TY5 and YR5 was used as a probe to determine structural perturbation of the peptides upon incubation and the putative role of the interactions involved. It is noteworthy to mention that there are two Tyr residues in each of the peptide. The intensity for emission maxima of Tyr was increased gradually with increasing the incubation time period for TK9 as well as TY5 and YR5 (Figure 3A). This enhancement was attributed to the change in the local environment of the fluorophore from a hydrophilic to a more hydrophobic environment. Initially, the Tyr residues were randomly oriented in solution where solvent molecule could easily quench their fluorescence intensity. However, the fluorescence emission maxima increased almost 4 times for TK9 and TY5 from 5 days of incubation time to 25 days of incubation time (Figure 3A). In contrast, the emission maxima of YR5 increased much less compared to that of TK9 (Figure 3A). Conversely, the incremental increase in fluorescence intensity of emission maxima for YR5 was negligible and reached a plateau after 25 days of incubation (Figure 3A), suggesting YR5 may not form an ordered aggregate in solution.

Figure 3.

(A) Tyrosine fluorescence of TK9 (red), TY5 (black) and YR5 (blue) monitoring increase in Tyr fluorescence signal as peptide aggregates. (B) Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assay measuring β-sheet rich fibril formation of freshly dissolved TK9 (black) and after 16 days of TK9 incubation (red).

Furthermore, thioflavin T (ThT) assays was performed to measure the higher order aggregation of TK9 over time. It is noteworthy to mention that, ThT is small molecule and specifically bind to the β-sheet rich amyloid fibrils.38 Figure 3B shows the fluorescence intensity of ThT, binding to peptide, TK9. The freshly dissolved TK9, incubated with ThT demonstrated very low fluorescence intensity. However as TK9 allowed to self assemble for 16-days, a greater extent of fluorescence intensity of ThT at approx. 490 nm was displayed, indicative of the presence of a β-sheet rich species. This result further confirms that the aggregation propensity of TK9 in solution increases over time. Collectively, these results suggest that the non-covalent π-π stacking interaction between the Tyr residues in the supramolecular structures of the aggregated states create a hydrophobic environment (β-sheet structure) where the entrance of water molecule is restricted and hence enhances the fluorescence emission maxima and interacts with the ThT dye.

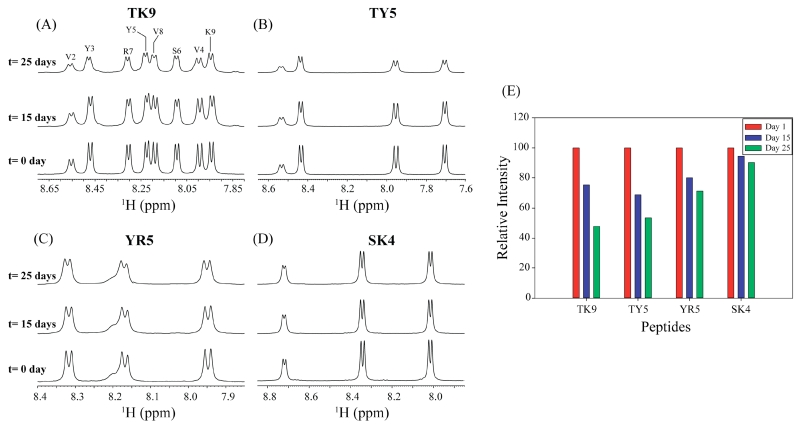

1H NMR confirms the aggregation propensity of TK9

NMR spectrum of TK9, or its analogs, exhibited well-resolved narrow amide proton peaks indicating that the peptides are highly dynamic in aqueous solution (Figure 4). A 2D TOCSY, in conjunction with ROESY, spectrum was used to assign the peaks (Figure S6). The ROESY spectrum of TK9 contained intra-residue αN (i, i) as well as sequential, αN (i, i+1) ROEs between backbone and side chain resonances (Figure S6A), and no medium range αN (i to i+2/i+3/i+4) or long-range αN (i to ≥i+5) cross peaks were observed, indicating that the peptide does not adopt any folded conformation (Figure S6 and S7). In addition, ΔHα values of the residues did not show any pattern of secondary structure (data not shown). A total of 47 ROEs (Table S2) were used to calculate the random coil structure of TK9 (Figure S7), which is also confirmed by the CD data (Figure 1).

Figure 4.

(A) Amide proton chemical shift regions of 1HNMR spectra of TK9 (A), TY5 (B), YR5 (C) and SK4 (D); (E) average decrease in peak intensity for each peptide. Spectra obtained after 0, 15 and 25 days incubation period are overlaid.

To determine the extent of aggregation as a function of time, we collected a series of 1D 1H NMR spectra of all the peptides in different time intervals of incubation. Figure 4 shows the amide proton chemical shift regions for TK9 and its analogues at the same time intervals. While freshly prepared peptides exhibited well-dispersed narrow peaks from amide protons, line broadening was observed with time of incubation (Figure 4A-4D). TK9 and TY5 showed the highest amount of line broadening with respect to time, whereas SK4 showed the least line broadening (Figure 4E). The observed line broadening in NMR spectra due to the chemical exchange process, occurring in millisecond to microsecond time scale can be attributed to peptide aggregation, which could result in the formation of high molecular weight assemblies. This effect was further confirmed by proton relaxation studies.

1H NMR relaxation studies are used extensively as a sensitive probe to investigate the weak interactions (dissociation constant, Kd ~ μM to mM range) in peptide oligomerization.39 The formation of oligomers with high molecular weights gives rise to increased correlation times (τc), is revealed by the longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) relaxation rates that they have direct relationships with the correlation time (τc) of a molecule. Interestingly, the N-terminal residues of TK9, Val2-Arg7 show a drastic decrease of R1 values for aged samples of TK9 in comparison to freshly prepared TK9, indicating the restricted dynamics of its oligomeric form (Figure 5A). The R1 values of Val8 and Lys9 of aged sample and freshly prepared TK9 were almost equal. A similar profile was observed for the R2 profile. The increase in R2 was a direct consequence of the increased line widths (Figure 5B). Qualitatively, all the residues of aged TK9 sample showed higher R2 values in comparison to the freshly prepared TK9. However, the C-terminal residues, Arg7-Val8-Lys9 showed less increment of R2 values for the aged sample of TK9. Overall, the relaxation data suggest the presence of high molecular weight oligomers in aged samples of TK9.

Figure 5.

The residue wise relaxation profile for freshly prepared TK9 (blue) and 25 days incubated TK9 (red). (A) Longitudinal relaxation rate (R1) and (B) transverse relaxation rate (R2) are plotted for each residue of TK9.

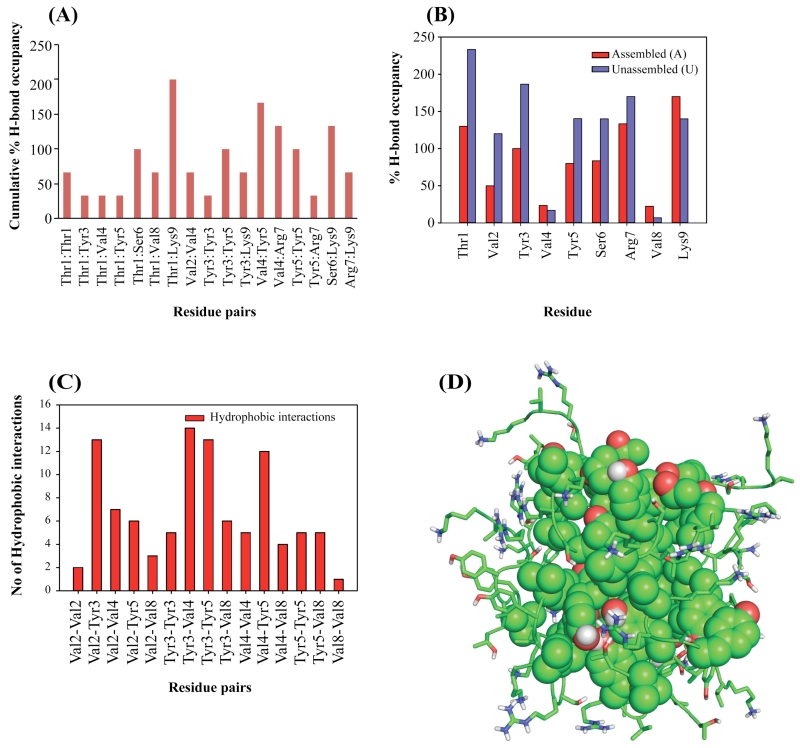

Simulations suggest that both local and global orientation of TK9 may influence aggregation

The above experimental result motivated us to determine the mechanism of aggregation of a small peptide, TK9. Interestingly, among the nine amino acid residues, there are two aromatic amino acid residues, Tyr, three hydrophobic Val residues, two positive charge Lys and Arg and two β-branched amino acid residues, Thr and Ser. The NMR derived extended conformation of TK9 (Figure S6C) was used as an initial structure for the coarse grained (CG) molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. It is noteworthy to mention that the self-assembly of a short peptide occurs at a μs time scale, and hence it is a time consuming process to carry out all atom MD simulation.40 To overcome this problem, coarse-grained MD simulation was adopted to study the aggregation of TK9 with twenty TK9 peptide chains.

Figure S2 summarizes the stages of aggregation of TK9. Interestingly, the scattered monomers started self-assembling after 27 ns of simulation and the cluster size was increasing as the time progressed. Finally, after 999 ns of simulation, fifteen out of twenty TK9 peptide chains were self-assembled to form the TK9 aggregate (Figure S2). The remaining five TK9 monomers were still scattered after 1 μs of simulation. Next, we wanted to understand the driving force of the aggregation for TK9. The secondary structure analysis of the assembled as well as the scattered molecules were performed using the Stride web interface.41 Interestingly, we found that the 60% of conformation of assembled peptide possess a beta turn and more than 35% of conformation exists as random coil (Table S3).

Closer inspection indicated that the self-assembly of TK9 (Figure 6) was stabilized by a variety of interactions, such as H-bonding, electrostatic, π-cation and van der Waals. The C-terminal positively charged Lys9 residue of TK9 contributed for a H-bonding interaction with Thr1 and with Ser6. In addition, H-bonding contributions were also observed between Thr1-Ser6, Tyr3-Tyr5, Val4-Tyr5, Val2-Val4 and Thr1-Thr1 of TK9 in an assembled state. Apart from the H-bonding interactions between two self-assembled monomers, polar residues such as Arg7 and Lys9 formed numerous intermolecular salt bridge interactions (Table S4). Hydrophobic contacts were also observed between Val2-Tyr3, Val4-Tyr3, TYR5-Val4, Val2-Val4, Val2-Tyr5 and Tyr3-Val8, which may also play an important role in the aggregated form of TK9 (Figure 6). Interestingly, Tyr3-Tyr3, Tyr5-Tyr5 and Tyr3-Tyr5 aromatic interactions between two monomers of TK9 aggregates were crucial for stabilization. This result was in very good agreement with the Tyr fluorescence intensity enhancement in the aggregated state (Figure 6). A few cation-π interactions between Tyr3-Arg7, Tyr5-Arg7 and Tyr5-Arg9 were also observed in the fibrillar TK9 (Table S5).

Figure 6.

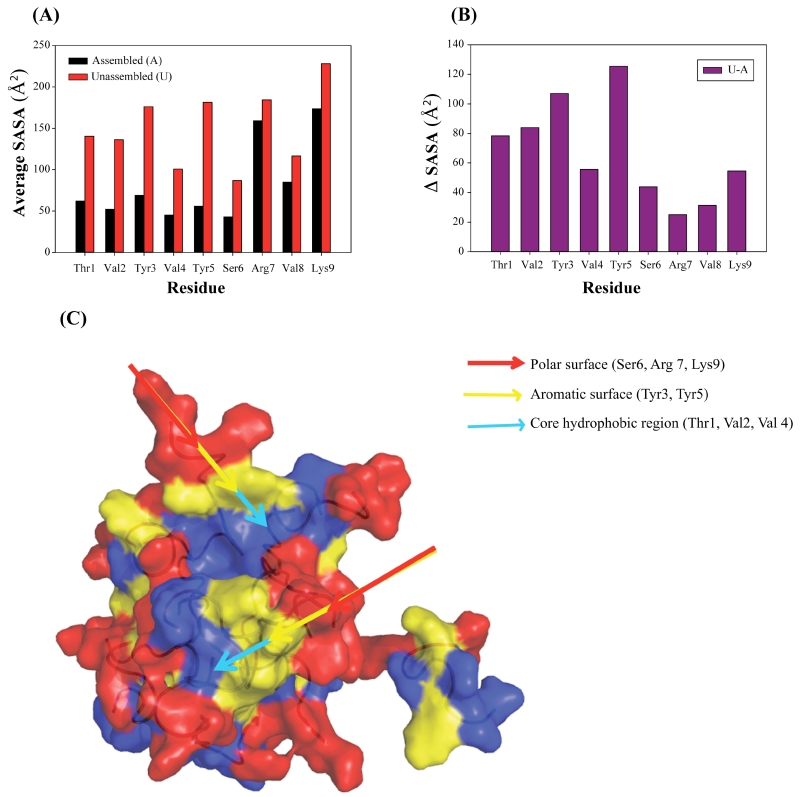

(A) Pairwise hydrogen bond analysis between any two monomers. Cumulative % H bond occupancy is calculated for respective residue pair in each peptide. (B) Percentage of H-bond occupancy of respective residue in each monomer was calculated to understand the amino acid-solvent interactions. Red bar represents the assembled and blue bar represents unassembled aggregation of each monomer of TK9. (C) Total number of hydrophobic interactions for respective residue pair is calculated for all the peptides forming cluster. (D) Oligomeric structure of TK9 is stabilized by hydrophobic hub consisting Tyr, Val, Ser and Thr residues. Positively charged residues are exposed to water.

Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) data was evaluated to suggest the conformation of the biomolecule. The SASA values of each residue of TK9 aggregate as well as in the scattered monomers after 1 μs of simulation were calculated (Figure 7) and it was clear that the overall SASA values for all the residues in the cluster or aggregated form was lower, whereas, the same amino acid residues in the scattered peptides (monomer) were much higher. The standard deviation of SASA values of each residue of scattered peptides was less compared to that of aggregated peptides. This behavior could be due to folded conformation in the aggregated form and hence they were less accessible to the solvent. On the other hand, the short peptide TK9 is highly dynamic in nature and therefore, the peptide is more solvent exposed in the unfolded form. Interestingly, the C-terminal residues, Arg7, Val8 and Lys9 showed comparably higher SASA values both in the scattered as well as in the aggregated form (Figure 7). Taken together, the central stabilization of the assembly of TK9 was due to the strong van der Waals interactions between hydrophobic Val residues as well as between aromatic Tyr residues. In comparison, the Arg7 and Lys9 residues of TK9 aggregates were pointing towards the solvent to form H-bond with the solvent water molecules.

Figure 7.

(A) Comparative analysis of the average SASA for each residue in assembled and unassembled state. Black represents the assembled state while red represents the unassembled state. (B) ΔSASA (ΔSASA=SASAunassembled - SASAassembled) values for each residue. (C) Surface view of cluster illustrating polarities of residues with color discrimination.

TK9 inhibits hIAPP aggregation

In order to uncover the potential role of the self-assembling TK9 peptide on amyloid aggregation, it was co-incubated with freshly dissolved hIAPP and assayed using ThT to monitor β-sheet rich fibril formation. At a stoichiometric concentration of TK9 monomer, hIAPP still adopted a normal course of aggregation; however, the lag phase was increased and the total fibrillar hIAPP fluorescence intensity was decreased (Figure 8A). With the increased concentration of TK9, hIAPP aggregation was completely diminished. Similarly, incubation of freshly dissolved hIAPP with excess TK9 over 8 hr displayed mainly a random coil peptide in solution as shown by CD experiments (Figure 8B). When TK9 fibril was added to hIAPP solution, aggregation of hIAPP was slightly modified, suggesting possible interactions between TK9 and hIAPP.

Figure 8.

(A) ThT fluorescence assay of hIAPP (black) solution incubated with 1 (red) and 2 (blue) equivalents of TK9; ThT aggregation of TK9 peptide in solution is shown in the green trace. (B) CD spectra of freshly dissolved hIAPP (black) and hIAPP incubated over 6 hours with 2 equivalents of TK9 at the indicated time intervals of aggregation. (C) One dimensional 1H NMR spectrum of freshly dissolved TK9 in hIAPP (monomer) (top, control); STD spectrum in the presence of hIAPP monomer at t = 12 h. (middle) and in the presence of hIAPP fibril (bottom).

The inhibition of hIAPP aggregation by TK9 was further confirmed by 1H STD NMR experiments. STD has become a valuable technique to map the interaction of ligands with biomolecules.42-44 Freshly prepared hIAPP monomers were added to a solution of TK9 monomers and monitored by NMR for more than 12 hr. Both the receptor, hIAPP, as well as the ligand, TK9, are low-molecular weight molecules; therefore, no STD signals from TK9 in the presence of hIAPP monomers were observed due to the fast tumbling of TK9. However, if hIAPP fibrillizes, it should be possible to transfer the magnetization from the large-size hIAPP fibrils to TK9 peptide in STD experiments. But, the fact that we did not observe STD signal within a period of 12 hours indicates that hIAPP did not exist in fibrillar form (Figure 8C), as hIAPP (in the absence of TK9) completely fibrilizes within 3 hours at the same condition as seen by the ThT assay (Figure 8C). In addition, when TK9 monomers were incubated with hIAPP fibrils, a pronounced STD signal was observed from aromatic as well as aliphatic amino acid residues, indicating that the aromatic and methyl protons are responsible for interacting with fibrillar hIAPP. These observations confirm the ability of TK9 to inhibit hIAPP aggregation to form an ordered secondary structure.

DISCUSSION

According to the current trend in nanoscience, synthetic amphiphilic small peptides emerge as versatile building block for the fabrication of supramolecular architecture.45 The ability of these peptides to assemble into ordered nanostructures may help to better understand the natural misfolding pathway of systems such as amyloid proteins.46 In these systems, short peptide fragments in the wild-type sequence (KLVFF for amyloid-β and NFGAIL for hIAPP) have been identified to be responsible for β-sheet formation thus more clearly investigating the properties and features of small peptide assemblies can help in better understanding larger protein systems.47-49 The self-assembly regions have also served as a template to rationally design amyloid inhibitors by blocking β-sheet formation, therefore; short peptide fragments of amyloid proteins can also help elucidate possible sequence motifs for therapeutic design and development.50-52

The aim of this study has been to reveal self-assembly activity of the ultra small peptide, TK9 and its variants through biophysical, NMR and computational methods. TK9 and TY5 both contain branched, bulky amino acids and a specific sequence (VxVx, Scheme 1) that has been shown to be prone to amyloid-like aggregation.53 Over time, TK9 spontaneously aggregated in aqueous solution as seen by DLS (Figure 1) to adopt rod-like fibrillar morphology, confirmed by microscopic studies (Figure 2). Interestingly, the aggregation was β-sheet rich, examined by the increase in ThT fluorescence (Figure 3). All four peptides adopt a random coil monomeric conformation at early time points; however, CD experiments confirmed that TK9 and TY5 form into a β-sheet containing fibrillar species after incubation over days (Figure 1B and 1C). In addition, because of the presence of the “amyloid aggregation-prone” sequence motif, a further explanation for the aggregation propensity of TK9 and TY5 may be the increase in hydrophobic and aromatic residues, which may favor hydrophobic contacts and π-π interactions as well as undergo a transition to β-sheet during self-assembly more readily than peptides with aliphatic residues.53

Structurally different, YR5 and SK4, which do not contain the aggregation-prone sequence, did not show this transition to β-sheet nor did they show an enhanced ThT fluorescence, suggesting an ill-defined secondary structure. The distribution profile of the peptides is also varied upon aggregation as suggested by the DLS studies (Figure 1A). As the peptides were incubated, the size of the species increased, which may be attributed to the fibril-like aggregates formed in the case of TK9 and TY5. The π-π interactions could be the governing factor for the folding of the peptide into supramolecular assemblies as seen by Tyr fluorescence experiments (Figure 3). As TK9 is allowed to self-assemble, it forms a hydrophobic core, which does not allow for interactions with water, and thus an enhancement in the Tyr fluorescence signal by neighboring Tyr residues. Coarse grain MD simulation confirms that the self-assembled oligomer of TK9 is stabilized by hydrophobic amino acid residues such as, Tyr and Val from individual monomers to form a hydrophobic hub and all the charge residues such as Arg7 and Lys9 are exposed to water (Figure 6). In contrary, the solvent quenches the fluorescence intensity of TK9 or TY5 monomer (Figure 3). However, a well-defined secondary structure of YR5, the central region of TK9, was not observed. In order to probe the mechanistic insights of self-assembly of a short peptide at an atomic resolution, NMR spectroscopy was carried out.

Proton NMR and relaxation studies further confirm the presence of high molecular weight oligomers in aged samples. In 1H NMR spectra, amide resonances are observed for all of the peptides at initial time points. As the peptides are allowed to self-assemble, significant line broadening is visible for TK9 and TY5, whereas a lesser broadening is seen for YR5 and SK4 over the time course (Figure 4). The line broadening observed for TK9 or TY5 peptides confirms that there is a conformational exchange between several states that occur at the millisecond to microsecond time scale. This dynamic behavior may further confirm an aggregation process occurring in solution, specifically the formation of high molecular weight assemblies that tumble slowly in NMR time scale, which gave rise to an increased rotational correlation time (Figure 5). The TOCSY and ROSEY data, taken of freshly prepared monomers, show no medium or long range cross peaks (or ROEs), confirming the absence of a well-defined secondary structure (possibly random coil) prior to incubation (Figure S6).

Furthermore, the applications of these self-assembled peptides are of great value since they do have interesting intrinsic properties; however, their role in understanding protein-protein interactions may also be useful. Investigations of the interaction between amyloid proteins and other biologically relevant proteins have been of great interest. Specifically, reports regarding the interaction of co-secreted proteins, hIAPP and insulin, has shed light into the involvement of a protein on amyloid formation.54,55 Aforementioned, small peptide sequence from the native protein have been utilized in the design of amyloid inhibitors due to their ability to contain self-recognition motifs which can interact with the target protein through hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions and prevent polymerization to fibrils.50,56,57 In order to study this, we tested the inhibitory activity of TK9 against hIAPP, an amyloid protein suggested to be a pathological feature of type-2 diabetes. Our experimental results indicate that the amyloid-inhibition properties of TK9 monomers are concentration dependent as shown in Figure 8. This observation is similar to that shown for amyloid-inhibiting properties of a 9-residue peptide, NK9 (or 45NIVNVSLVK53) adopted from SARS CoV E-protein, against the fibrillation of insulin.58 Interestingly, TK9 monomers are able to modify the aggregation kinetics of hIAPP and completely inhibit the fibril formation upon incubation with excess amount of a TK9. This result was further verified by STD NMR experiments, which showed that upon incubation of hIAPP monomers with excess TK9 monomers, no pronounced STD effect was observed indicating the presence of a small, insufficient amount of hIAPP fibers. On the other hand, when TK9 monomers are present in a solution along with hIAPP fibrils, a strong STD signal was observed, confirming an interaction between the two peptides.

Overall, the study of self-assembled peptides nanostructures can serve, as useful systems for understanding more global systems, like amyloid proteins kinetics and aggregation at the atomic level. Herein, the aggregation properties of TK9 and its variants were characterized through biophysical, spectroscopic and simulated studies, and it was confirmed that the structure of these peptides influence their aggregation propensity and fibrillar morphology. TK9 underwent a transition to a more β-sheet rich structure, which adopted a fibril-like shape. These aggregates were further investigated through simulations to understand more clearly the possible intra- and inter peptide interactions at the molecular level. As described here, self-assembly peptides may also be useful templates for designing amyloid inhibitor. These self-assembly systems may also be used in understanding the molecular and structural biology which will inspire the design and synthesis of increasingly complex self assembled biomaterials for biomedicine. Furthermore, investigations to probe the structural characteristics of these peptides in the presence of membrane can also be of great value since the amyloid beta or hIAPP protein interacts with membrane before going to fibrillation.59-61 Therefore, instead of using the entire protein of amyloid-β or hIAPP in membrane, this peptide can be a nanoindicator to understand the structural insight at the membrane surface for the mechanism of fibrillation process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

AB would like to thank Bose Institute, Kolkata, India for financial support. AG thanks CSIR, Govt. of India for senior research fellowship. SB thanks Bose Institute, Kolkata for M. Sc. – Ph.D fellowship. Central instrument facility (CIF) of Bose Institute is greatly acknowledged. Part of this study, and AB and ASP were supported by funds from NIH (GM084018 to A.R.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- hIAPP

human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide Protein

- DLS

Dynamic Light Scattering

- CD

Circular Dichroism

- NMR

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

- MD

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

- SEM

Scanning Electron Microscopy

- ROESY

Rotating Frame Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy

- STD

Saturation Transfer Difference spectroscopy

- TEM

Transmission Electron Microscopy

- ThT

thioflavin T

- TOCSY

Total Correlation Spectroscopy

Footnotes

This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Gazit E. Self-assembled peptide nanostructures: the design of molecular building blocks and their technological utilization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1263–1269. doi: 10.1039/b605536m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Zhao X, Pan F, Xu H, Yaseen M, Shan H, Hauser CA, Zhang S, Lu JR. Molecular self-assembly and applications of designer peptide amphiphiles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:3480–3498. doi: 10.1039/b915923c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zhang S. Fabrication of novel biomaterials through molecular self-assembly. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1171–1178. doi: 10.1038/nbt874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Whitesides G, Mathias J, Seto C. Molecular self-assembly and nanochemistry: a chemical strategy for the synthesis of nanostructures. Science. 1991;254:1312–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1962191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Lecommandoux S, Achard M-F, Langenwalter JF, Klok H-A. Self-assembly of rod-coil diblock oligomers based on α-helical peptides. Macromolecules. 2001;34:9100–9111. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lawrence DS, Jiang T, Levett M. Self-assembling supramolecular complexes. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:2229–2260. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lakshmanan A, Zhang S, Hauser CA. Short self-assembling peptides as building blocks for modern nanodevices. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hosseinkhani H, Hong P-D, Yu D-S. Self-assembled proteins and peptides for regenerative medicine. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:4837–4861. doi: 10.1021/cr300131h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Yemini M, Reches M, Rishpon J, Gazit E. Novel electrochemical biosensing platform using self-assembled peptide nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2005;5:183–186. doi: 10.1021/nl0484189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ross CA, Poirier MA. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Knowles TP, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM. The amyloid state and its association with protein misfolding diseases. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2014;15:384–396. doi: 10.1038/nrm3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Chiti F, Dobson CM. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lu K, Jacob J, Thiyagarajan P, Conticello VP, Lynn DG. Exploiting amyloid fibril lamination for nanotube self-assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6391–6393. doi: 10.1021/ja0341642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wilson L, Mckinlay C, Gage P, Ewart G. SARS coronavirus E protein forms cation-selective ion channels. Virology. 2004;330:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Verdiá-Báguena C, Nieto-Torres JL, Alcaraz A, DeDiego ML, Torres J, Aguilella VM, Enjuanes L. Coronavirus E protein forms ion channels with functionally and structurally-involved membrane lipids. Virology. 2012;432:485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Li Y, Surya W, Claudine S, Torres J. Structure of a Conserved Golgi Complex-targeting Signal in Coronavirus Envelope Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:12535–12549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.560094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Chan WC, White PD. Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis. Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ghosh A, Datta A, Jana J, Kar RK, Chatterjee C, Chatterjee S, Bhunia A. Sequence context induced antimicrobial activity: insight into lipopolysaccharide permeabilization. Molecular BioSystems. 2014;10:1596–1612. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00111g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lakowicz JR. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Goddard T, Kneller D. SPARKY 3. Vol. 14. University of California; San Francisco: 2004. p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Güntert P. Protein NMR Techniques. Springer; 2004. Automated NMR structure calculation with CYANA; pp. 353–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ghosh A, Kar RK, Jana J, Saha A, Jana B, Krishnamoorthy J, Kumar D, Ghosh S, Chatterjee S, Bhunia A. Indolicidin Targets Duplex DNA: Structural and Mechanistic Insight through a Combination of Spectroscopy and Microscopy. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:2052–2058. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ghosh A, Kar RK, Krishnamoorthy J, Chatterjee S, Bhunia A. Double GC: GC Mismatch in dsDNA Enhances Local Dynamics Retaining the DNA Footprint: A High-Resolution NMR Study. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:2059–2064. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Marrink SJ, de Vries AH, Mark AE. Coarse grained model for semiquantitative lipid simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:750–760. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Marrink SJ, Risselada HJ, Yefimov S, Tieleman DP, de Vries AH. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hess B, Kutzner C, Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rzepiela AJ, Schäfer LV, Goga N, Risselada HJ, De Vries AH, Marrink SJ. Reconstruction of atomistic details from coarse-grained structures. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:1333–1343. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hoover WG. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A. 1985;31:1695. doi: 10.1103/physreva.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Oostenbrink C, Villa A, Mark AE, Van Gunsteren WF. A biomolecular force field based on the free enthalpy of hydration and solvation: The GROMOS force-field parameter sets 53A5 and 53A6. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1656–1676. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Cohen JR, Lin LD, Machamer CE. Identification of a Golgi complex-targeting signal in the cytoplasmic tail of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein. J. Virol. 2011;85:5794–5803. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00060-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Fukushi S, Mizutani T, Sakai K, Saijo M, Taguchi F, Yokoyama M, Kurane I, Morikawa S. Amino acid substitutions in the s2 region enhance severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infectivity in rat angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-expressing cells. J. Virol. 2007;81:10831–10834. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01143-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Nieto-Torres JL, DeDiego ML, Álvarez E, Jiménez-Guardeño JM, Regla-Nava JA, Llorente M, Kremer L, Shuo S, Enjuanes L. Subcellular location and topology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein. Virology. 2011;415:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ruch TR, Machamer CE. The hydrophobic domain of infectious bronchitis virus E protein alters the host secretory pathway and is important for release of infectious virus. J. Virol. 2011;85:675–685. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01570-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Halverson K, Fraser PE, Kirschner DA, Lansbury PT., Jr Molecular determinants of amyloid deposition in Alzheimer’s disease: conformational studies of synthetic. beta.-protein fragments. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2639–2644. doi: 10.1021/bi00463a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Remington JS, Klein JO, Wilson CB, Nizet V, Maldonado Y. Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn. Infectious disease of the fetus and newborn. 2001;12:643–681. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Berne BJ, Pecora R. Dynamic light scattering: with applications to chemistry, biology, and physics. Courier Dover Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Westermark P, Engström U, Johnson KH, Westermark GT, Betsholtz C. Islet amyloid polypeptide: pinpointing amino acid residues linked to amyloid fibril formation. PNAS. 1990;87:5036–5040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Levine H. Thioflavine T interaction with synthetic Alzheimer’s disease β-amyloid peptides: Detection of amyloid aggregation in solution. Protein Sci. 1993;2:404–410. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Esposito V, Das R, Melacini G. Mapping polypeptide self-recognition through 1H off-resonance relaxation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9358–9359. doi: 10.1021/ja051714i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Klein ML, Shinoda W. Large-scale molecular dynamics simulations of self-assembling systems. Science. 2008;321:798–800. doi: 10.1126/science.1157834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Heinig M, Frishman D. STRIDE: a web server for secondary structure assignment from known atomic coordinates of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W500–W502. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Bhunia A, Bhattacharjya S, Chatterjee S. Applications of saturation transfer difference NMR in biological systems. Drug Discovery Today. 2012;17:505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Mayer M, Meyer B. Characterization of ligand binding by saturation transfer difference NMR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:1784–1788. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990614)38:12<1784::AID-ANIE1784>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Yesuvadian R, Krishnamoorthy J, Ramamoorthy A, Bhunia A. Potent γ-secretase inhibitors/modulators interact with amyloid-β fibrils but do not inhibit fibrillation: A high-resolution NMR study. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;447:590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Rajagopal K, Schneider JP. Self-assembling peptides and proteins for nanotechnological applications. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Dobson CM. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature. 2003;426:884–890. doi: 10.1038/nature02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Tjernberg LO, Näslund J, Lindqvist F, Johansson J, Karlström AR, Thyberg J, Terenius L, Nordstedt C. Arrest of-amyloid fibril formation by a pentapeptide ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:8545–8548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Kapurniotu A, Schmauder A, Tenidis K. Structure-based design and study of non-amyloidogenic, double N-methylated IAPP amyloid core sequences as inhibitors of IAPP amyloid formation and cytotoxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;315:339–350. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Gazit E. Self assembly of short aromatic peptides into amyloid fibrils and related nanostructures. learning. 2007;17:18. doi: 10.4161/pri.1.1.4095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Tatarek-Nossol M, Yan L-M, Schmauder A, Tenidis K, Westermark G, Kapurniotu A. Inhibition of hIAPP amyloid-fibril formation and apoptotic cell death by a designed hIAPP amyloid-core-containing hexapeptide. Chemistry & biology. 2005;12:797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Watanabe K.-i., Nakamura K, Akikusa S, Okada T, Kodaka M, Konakahara T, Okuno H. Inhibitors of fibril formation and cytotoxicity of β-amyloid peptide composed of KLVFF recognition element and flexible hydrophilic disrupting element. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;290:121–124. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Gazit E. Mechanisms of amyloid fibril self-assembly and inhibition. Febs Journal. 2005;272:5971–5978. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).de la Paz ML, Serrano L. Sequence determinants of amyloid fibril formation. PNAS. 2004;101:87–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2634884100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Brender JR, Lee EL, Hartman K, Wong PT, Ramamoorthy A, Steel DG, Gafni A. Biphasic effects of insulin on islet amyloid polypeptide membrane disruption. Biophys. J. 2011;100:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Susa AC, Wu C, Bernstein SL, Dupuis NF, Wang H, Raleigh DP, Shea J-E, Bowers MT. Defining the Molecular Basis of Amyloid Inhibitors: Human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide-Insulin Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12912–12919. doi: 10.1021/ja504031d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Tjernberg LO, Lilliehöök C, Callaway DJ, Näslund J, Hahne S, Thyberg J, Terenius L, Nordstedt C. Controlling amyloid β-peptide fibril formation with protease-stable ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:12601–12605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Mishra A, Misra A, Vaishnavi TS, Thota C, Gupta M, Ramakumar S, Chauhan VS. Conformationally restrictred short peptides inhibit human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP) fibrillization. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:2688–2690. doi: 10.1039/c3cc38982k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Banerjee V, Kar RK, Datta A, Parthasarathi K, Chatterjee S, Das KP, Bhunia A. Use of a small peptide fragment as an inhibitor of insulin fibrillation process: A study by high and low resolution spectroscopy. PloS one. 2013;8:e72318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Brender JR, Salamekh S, Ramamoorthy A. Membrane disruption and early events in the aggregation of the diabetes related peptide IAPP from a molecular perspective. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;45:454–462. doi: 10.1021/ar200189b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Patel HR, Pithadia AS, Brender JR, Fierke CA, Ramamoorthy A. In Search of Aggregation Pathways of IAPP and other Amyloidogenic Proteins: Finding Answers Through NMR Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:1864–1870. doi: 10.1021/jz5001775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Qiang W, Akinlolu RD, Nam M, Shu N. Structural Evolution and Membrane Interaction of the 40-Residue beta Amyloid Peptides: Differences in the Initial Proximity between Peptides and the Membrane Bilayer Studied by Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2014;53:7503–7514. doi: 10.1021/bi501003n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.