Abstract

Objective:

Increased susceptibility to emotional triggers and poor response inhibition are important in the etiology of violence in schizophrenia. Our goal was to evaluate abnormalities in neurophysiological mechanisms underlying response inhibition and emotional processing in violent patients with schizophrenia (VS) and 3 different comparison groups: nonviolent patients (NV), healthy controls (HC) and nonpsychotic violent subjects (NPV).

Methods:

We recorded high-density Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) and behavioral responses during an Emotional Go/NoGo Task in 35 VS, 24 NV, 28 HC and 31 NPV subjects. We also evaluated psychiatric symptoms and impulsivity.

Results:

The neural and behavioral deficits in violent patients were most pronounced when they were presented with negative emotional stimuli: They responded more quickly than NV when they made commission errors (ie, failure of inhibition), and evidenced N2 increases and P3 decreases. In contrast, NVs showed little change in reaction time or ERP amplitude with emotional stimuli. These N2 and P3 amplitude changes in VSs showed a strong association with greater impulsivity. Besides these group specific changes, VSs shared deficits with NV, mostly N2 reduction, and with violent nonpsychotic subjects, particularly P3 reduction.

Conclusion:

Negative affective triggers have a strong impact on violent patients with schizophrenia which may have both behavioral and neural manifestations. The resulting activation could interfere with response inhibition. The affective disruption of response inhibition, identified in this study, may index an important pathway to violence in schizophrenia and suggest new modes of treatment.

Key words: aggression, response inhibition, emotional triggers, impulsivity, electrophysiology

Introduction

Aggressive behavior in individuals with schizophrenia has serious clinical and societal consequences, but is still poorly understood. It is often associated with dysregulation of emotion and impaired impulse control.1,2 The ability to adequately inhibit responses in the context of emotion, in particular negative emotions, is essential for control of violent behavior. Heightened susceptibility to affective triggers disrupts emotion regulation and interferes with response inhibition; this may lead to violence,3 more specifically to “impulsive-emotional violence.”4,5 People with schizophrenia are at increased risk for this type of violence, possibly due to affective dysregulation and impaired response inhibition, which are core deficits in this disorder.6,7

Individuals predisposed to aggression may have abnormalities in the neural circuitry responsible for response inhibition and emotional processing.3 Imaging studies indicate that the neural activity related to these 2 processes are closely interrelated.8,9 Activation of limbic areas by affective stimuli suppresses activity in prefrontal cognitive control areas.10,11 The emotional impact of stimuli can interfere with response inhibition, as it places extra demands on neural resources.12 This is particularly true of schizophrenia where these resources are already compromised.

The Go/NoGo Task has been used as a measure of response inhibition in many electrophysiological studies. It elicits 2 important event-related potential (ERP) components: N2 (200–400ms post-stimulus) and P3 (300–500ms post-stimulus).13 The emotional Go/NoGo Task, which uses emotional stimuli, assesses also emotional reactivity; the affective valence of stimuli can independently modulate ERP outcomes.14

Enhanced NoGo P3 is considered a prominent index of response inhibition.15,16 Reduced P3 had been reported in violent subjects,17,18 including violent schizophrenic patients,19 subjects with impulsive or reactive aggression,17,18 or impaired impulsivity.20

The significance of the NoGo N2 component in cognitive control is not as clearly defined. It may indicate a wide range of cognitive control processes, such as response activation,21 or conflict monitoring22 rather than response inhibition itself. N2 reflects also aspects of emotional processing.23,24 Unpleasant or threatening stimuli, in particular, increase N2 amplitude.25 This may be the result of rapid amygdala activity in the processing of aversive information.26 N2 increase to unpleasant/threatening stimuli is particularly strong in subjects who are sensitized to such stimuli, such as subjects with higher suspiciousness or anxiety.27

Because violent patients with schizophrenia may share characteristics with nonpsychotic violent subjects (NPV) and with nonviolent schizophrenic patients, we compared neurophysiological mechanisms underlying response inhibition and emotional processing in these groups. This allows us to disentangle the effects related to schizophrenia from those related to violence.

We hypothesized that increased emotional reactivity to negative stimuli contributes to deficient response inhibition in violent patients with schizophrenia. This is reflected in an increase in commission errors and in faster responding when committing such errors. It is expected that violent patients with schizophrenia will have the greatest number of commission errors and faster responding when committing such errors. It is also expected that they will exhibit a particular ERP pattern, ie, higher N2 and lower P3 when presented with negative stimuli.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Thirty-five violent patients (VS), 24 nonviolent patients (NV), 31 NPV and 28 healthy controls (HC) participated. They had no significant medical/neurological illnesses, no seizure disorder, and had not received ECT treatment. History of alcohol/drug abuse and dependence were obtained as part of the diagnostic assessment with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). Participants in all 4 groups who presented with any drug or alcohol abuse in the preceding 6 months were excluded from the study, so that the results would not be confounded by this factor. We obtained information about childhood/adolescence behavior problems (prior to age 15), including school truancy, school disciplinary problems (eg, suspension, expulsion from school), and fire-setting.

The SCID was administered to confirm diagnosis of schizophrenia in the patients (Patient Version) and the absence of any psychotic disorder in the non-patient groups (Non-Patient Version), as well as for drug and alcohol abuse. Patients were recruited from inpatient and outpatient units of a large state suburban hospital; non-patient participants were recruited from the community. All participants provided written informed consent according to a protocol approved by the institutional review boards and compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedures

Life History of Aggression.28

This scale was completed on the basis of all available information, including self-report, chart review, and official records of arrests, convictions, parole, and probation obtained from the Division of Criminal Justice Services. For inclusion as violent (VS or NPV), the participant was required to have a confirmed episode of physical assault within the past year, and a Life History of Aggression (LHA) score of ≥20. For inclusion as a nonviolent participant (HC or NV), the subject was required to have a LHA score ≤ 15, as indicated by the scale authors,28 and no episode of physical aggression over the past year, or any lifetime episode of severe physical aggression (ie, resulting in an injury requiring medical treatment).

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.29

This scale was used to assess psychiatric symptoms in patients. Interrater reliability, estimated by intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), exceeded 0.90. Five factors were used as determined by a factor analysis study30: Positive symptoms, negative symptoms, excitation, cognitive impairment and depression.

The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Version 11.31

This measure of impulsive traits often complements the Go/No Go Task, as it assesses personality traits, while behavioral procedures, such as the Go/No Go task, are more state-dependent.31

The Wide Range Achievement Test—Third Edition, Reading Subtest.32

The Wide Range Achievement Test—Third Edition, Reading Subtest (WRAT-3) is a well-accepted method of estimating premorbid academic skills and IQ.33

Stimuli and Go/NoGo Task

One of the most commonly used paradigms to assess behavioral inhibition is the Go/NoGo Task. The “emotional” Go/NoGo task yields the same measure of inhibition, but the substitution of affective stimuli for the usual cues provides additional information about emotional modulation of response inhibition.34 We used 478 images from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS).35

We applied a sampling with replacement procedure choosing images from a pool of 148 negative (average valence of 2.56); 158 neutral (average valence 5.2); and 172 positive (average valence: 7.4) pictures. Each block of stimuli consisted of 180 trials. Emotionally valenced and neutral stimuli were randomly presented with an approximately equal probability (25%, 25% and 50% rate for negative, positive and neutral stimuli, respectively). Images were presented centrally every 1000ms for 800ms with an inter-stimulus-interval of 200ms. Images subtended 8.6° horizontally by 6.5° vertically. Participants had to respond to all stimuli, except for stimuli that were repeated twice in a row. The probability of No-Go trials was .15. Images were selected so that neutral, positive and negative images did not differ in luminance, contrast and spatial frequency, based on the Delplanque procedure.36

Procedure

Participants sat in a sound-attenuated, electrically shielded room, 115cm from the monitor. A central fixation cross superimposed to the images was presented and participants were instructed to fixate the cross to minimize eye movements. Participants completed at least 1 mandatory practice block prior to the experiment. Fourteen experimental blocks were run, each lasting 3.5 minutes with mandatory 1 to 2 minutes breaks after 2 blocks to prevent fatigue.

ERP Recordings and Analysis

ERPs were acquired through the ActiveTwo Biosemi (Biosemi, Amsterdam, Netherlands) electrode system from 72 scalp electrodes (sampling rate: 512Hz, band-pass: D.C. −150 Hz). EEG signal processing was performed using Brain Electrical Source Analysis software (BESA GmbH; Version 5.1.8). Data were referenced offline to the nasion electrode-site. Epochs of 900ms, including a 100ms pre-stimulus baseline, were analyzed. Trials with eye movements and blinks were rejected offline using vertical and horizontal EOG records with an artefact criterion of ±120 µV relative to baseline. An automatic artefact rejection criterion of ±70 µV was used at all other scalp sites. After these artefact rejection procedures, the average number of accepted NoGo trials was 44, 27, 25 for HC, 36, 20, 21 for NV, 26, 16, 17 for VS, and 33, 24, 23 for NPV participants for neutral, positive, and negative stimuli, respectively.

We compared N2 and P3 activity evoked by neutral, negative, or positive stimuli in the 3 groups. N2 and P3 amplitudes were measured by defining time-windows centered on the latency of the peak amplitude. For N2, peak latency was 280ms with a time-window of ±50ms; for P3, peak latency was 450ms, with a time-window of ±75ms.37,38 Scalp regions-of-interest (ROIs) were computed by averaging across frontal (FP1/FPz/FP2/AF7/AF3/AFz/AF4/AF8/F7/F5/F3/F1/Fz/F2/F4/F6/F8), central (FC5/FC3/FC1/FCz/FC2/FC4/FC6/C5/C3/C1/Cz/C2/C4/C6), parietal (CP5/CP3/CP1/CPz/CP2/CP4/CP6/P5/P3/P1/Pz/P2/P4/P6), temporal (FT7/FT8/T7/T8/TP7/TP8) and occipital (PO7/PO3/POz/PO4/PO8/O1/Oz/O2) sites.

Statistical Procedures

We used Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) which takes into consideration group heterogeneity and incorporates the time-dependent correlation structure of the sampling points.39 Repeated measurements of the ERP amplitudes (in microvolts) in each time window of interest served as the dependent variables in the analyses. The independent variable was “group.” Age, gender, years of education, WRAT scores, inpatient/outpatient status, alcohol abuse/dependence (yes/no) and drug abuse/dependence (yes/no) served as fixed-effect covariates in all analyses.

A first-order autoregressive moving average correlation structure of the sampling points allowing for heterogeneity among groups was specified in the HLM model. Test of the Least Squares Mean (LSM) for each emotion indicated whether there was a statistically significant N2/P3 effect within a given group. In order to investigate valence effect between groups, we formulated pairwise contrasts between the within-group LSM estimates for each valence. Analyses were repeated for each of the 5 ROIs. The adaptive Hochberg procedure was used to adjust for multiple testing. For behavioral results (accuracy/reaction times) and clinical evaluations, we used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with group as between-subject and stimulus valence as within-subject factors.

For ERP data, in order to characterize statistical effect sizes for each valence in each group, we computed Cohen’s d for the effect magnitude in the above-mentioned time windows at each of the 5 ROIs. Cohen’s d was computed as the LSM estimate for the waveform divided by the pooled within-group standard deviation estimate from the primary HLM model. We considered absolute values of Cohen’s d between 0.20 and 0.39 as small, between 0.40 and 0.69 as medium, and from 0.70 as large effect sizes.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Variables

Table 1 displays demographic and clinical information. Overall and pairwise comparisons are provided. There were no group differences in gender or ethnicity, but there was a significant difference in years of education. The 2 patients groups differed in years of education, but were almost identical on the WRAT-3 (P = .99), a measure of premorbid level of education and premorbid IQ.33

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Healthy Controls (HC), and Non-Psychotic Violent Subjects (NPV), of Nonviolent (NV) and Violent (VS) Patients With Schizophreniaa

| Characteristics | HC N = 28 | NPV N = 31 | NV N = 24 | VS N = 35 | χ2, P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, N (%) | 22 (78.6) | 29 (93.5) | 19 (79.2) | 28 (80.0) | 3.31, .35 |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |||||

| Caucasian | 11 (39.3) | 7 (22.6) | 9 (37.5) | 7 (20.0) | |

| African American | 16 (57.1) | 21 (67.7) | 13 (54.2) | 26 (74.3) | 5.21, .52 |

| Hispanic | 1 (3.6) | 3 (9.7) | 2 (8.3) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Subjects with any abuse/dependenceb N (%) | 3 (10.7) | 22 (71.0) | 7 (29.2) | 21 (60.0) | |

| Alcohol abuse | 3 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 8.1, .04c |

| Alcohol dependence | 0 | 7 | 1 | 2 | |

| Cannabis abuse | 0 | 5 | 3 | 12 | 37.1, <.0001d |

| Cannabis dependence | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | |

| Cocaine abuse | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |

| Cocaine dependence | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other substance abuse | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Other substance dependence | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Childhood & adolescence problems (before age 16)e N (%) | 10 (35.7) | 26 (83.9) | 9 (37.5) | 24 (68.6) | 20.7, .0001 |

| School truancy | 3 | 19 | 6 | 14 | |

| Other school discipline problem | 10 | 17 | 4 | 22 | |

| Fire setting | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | |

| Inpatient status N (%) | __ | __ | 11 (45.8) | 27 (77.1) | 6.1, .01 |

| F, P | |||||

| Mean age, in years | 40.1 (9.8) | 39.4 (10.3) | 41.6 (9.4) | 35.3 (11.0) | 2.2, .09 |

| Years of education | 14.7 (1.7) | 12.4 (1.7) | 12.9 (2.0) | 11.7 (1.9) | 14.9, <.001 |

| Age at first hospitalization | __ | __ | 24.2 (6.2) | 22.4 (9.1) | 0.7, .41 |

| WRAT-3f scores | 48.4 (5.8) | 44.3 (5.3) | 43.6 (5.9) | 43.8 (5.7) | 5.6, .001 |

| PANSSg scores | |||||

| Total score | __ | __ | 76.5 (16.6) | 80.4 (15.6) | .02, .88 |

| Positive symptoms factor | __ | __ | 2.9 (1.2) | 3.4 (1.1) | 1.76, .19 |

| Negative symptoms factor | __ | __ | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.9) | 5.38, .02 |

| Excitation factor | __ | __ | 1.7 (0.8) | 2.2 (1.0) | 1.51, .22 |

| Cognitive impairment factor | __ | __ | 2.7 (0.9) | 2.6 (0.7) | 1.52, .22 |

| Depression factor | __ | __ | 2.2 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.9) | 3.66, .06 |

| Life History of Aggression (LHA) totalh | 13.2 (5.9) | 33.4 (9.2) | 10.1 (5.5) | 25.7 (5.5) | 73.3, <.001 |

| LHA aggressioni | 8.9 (3.9) | 19.7 (6.4) | 6.6 (4.7) | 15.9 (3.9) | 44.8, <.001 |

| LHA self directed aggressionj | 0.07 (0.37) | 0.77 (1.6) | 0.17 (0.48) | 0.76 (1.4) | 2.96, .04 |

| LHA, social consequences and antisocial behaviork | 4.3 (2.9) | 12.9 (3.0) | 3.0 (2.5) | 8.2 (3.4) | 62.3, <.001 |

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11l | 55.3 (8.3) | 66.5 (11.2) | 60.2 (11.5) | 62.4 (11.1) | 5.71, .001 |

| Antipsychotic dosage (chlorpromazine equivalents) | __ | __ | 1103.2 (660.4) | 1245.5 (649.6) | 0.71, .40 |

Note: aFor categorical variables data are presented as relative frequencies; for continuous variables means and SD’s are provided.

bThe table provides information about incidence of abuse or dependence. Some subjects present with abuse or dependence to more than 1 substance (subjects with abuse/dependence within 6 months prior to evaluation were not enrolled in the study).

cOverall chi-square is reported for alcohol abuse or dependence in the 4 groups. The HC-NPV comparison was the only to reach statistical significance (P = .005).

dOverall chi-square is reported for substance abuse or dependence in the 4 groups. All pairwise comparisons reached statistical significance (P < .05), except for the NPV-VS comparison which was not significant.

eOverall chi-square is reported for people presenting with any 1 of 3 problems, truancy, school discipline problems or fire setting. Frequency of these problems were significantly higher in each of the violent group as compared to each of the nonviolent group in pairwise comparisons (P < .01), but there were no significant differences between the 2 violent pairs and the 2 nonviolent pairs.

fWRAT-3. Wide Range Achievement Test (third edition) Reading Subtest.

gPANSS. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. For all PANSS factors, the score indicated in the table is the total score on that factor divided by the number of items which compose the factor.

hIn pairwise comparisons for the LHA Total score, NPV had higher aggression scores than each of the other 3 groups (P < .001); VS had higher violence than NV’s and HC’s (P < .001).

iIn pairwise comparisons for the LHA Aggression score, NPV had higher scores than all 3 groups (P < .01); VS higher than HC and NV (P < .01 for each); there was no difference between HC and NV.

jIn pairwise comparisons for the LHA Self-Directed Aggression, HC had lower score than VS and NPV (<.05 for both). There were no other differences.

kIn pairwise comparisons for the LHA Social Consequences and Antisocial Behavior, NPV had higher violence than each of the other 3 groups (P < .001); VS had higher violence than NV’s and HC’s (P < .001). There was no significant difference between HC’s and NV’s.

lIn pairwise comparisons for the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Version 11 (BIS-11), NPV’s score was significantly higher than HC’s (P < .001) and NV’s (P = .03), but not VS. VS’s score was higher than HC (P = .01) but not NV’s.

There was a significant pairwise difference in alcohol abuse/dependence between NPV’s and HC’s but not between the other groups. For drug abuse/dependence, all pairwise differences were significant except for NPV-VS. Childhood and adolescence behavior problems were more frequent in the violent groups as compared to the nonviolent groups (P < .01).

Diagnostic information was also obtained. In HC’s, 1 subject had a past history of major depressive disorder. In NPV’s, 7 subjects had a past history of major depressive disorder and 1 of anxiety disorder.

In pairwise comparisons for impulsivity, NPV’s Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Version 11 (BIS-11) score was significantly higher than HC’s and NV’s, but not VS’s. VS’s score was higher than NV’s, but the difference was not statistically significant. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Total score was similar in the 2 schizophrenic groups, but NV had significantly more severe negative psychotic symptoms, while VS had marginally higher Depression score. Depression was the only PANSS factor that was related to Total LHA score in the VS’s (r = .42, N = 35, P = .01).

Life History of Aggression

Differences in LHA between the violent and the nonviolent groups were expected, as this was a criterion for group formation. In pairwise comparisons, NPV had significantly higher LHA Total, “Aggression,” and “Social Consequences and Antisocial Behavior” scores than the other groups, including VS. To contrast the aggressive behaviors present in the 2 violent groups, we compared the LHA Aggression subscale items in the 2 groups. NPV had significantly more frequent episodes of tantrums (ie, “screaming, ranting and raving etc. in response to frustration”), verbal fighting, and assaults on property than VS (P < .001 for each pairwise comparison). There were no significant differences for the other 2 items, “physical fights” and “specific assaults on other people.”

Go/No Go Commission Errors: Accuracy and Reaction Times

There were significant overall group differences in commission errors for neutral (F = 14.9, df = 3,115, P < .001), positive (F = 17.9, df = 3,115, P < .001) and negative (F = 13.9, df = 3,115, P < .001) valences. Both patient groups made significantly more commission errors than HC and NPV for all 3 valences (P < .01 for all pairwise comparisons). NPV’s made more commission errors than HC’s. This difference was significant for the neutral (P = .02), positive (P < .01) and negative (P = .02) valences. The VS-NV difference, however, was not significant (P > .1).

There was an overall difference in reaction time for commission errors on stimuli with neutral (F = 6.0, df = 3,115, P < .001), positive (F = 10.6, df = 3,115, P < .001) and negative (F = 12.1, df = 3,115, P < .001) valences. In pairwise comparisons, patient groups responded more slowly than HC (P < .001) and NPV (P < .01) for all valences, while HC and NPV did not differ (P > .1). VS were significantly faster than NV for negative valence (P = .02), and marginally faster for positive valence (P = .07); there was no difference for neutral valences (P = .29).

In order to understand better the association between commission errors and certain schizophrenic symptoms, we obtained Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Commission errors were positively related to the PANSS Negative Symptom subscale among schizophrenic subjects (N = 56; r = .27, P = .04; r = .26, P = .05; r = .27, P = .04 for neutral, positive and negative valences, respectively). Furthermore, commission errors were positively related to the PANSS Poor Attention item, which provides a clinical assessment of general alertness including “difficulties in shifting focus to new stimuli”40 (p.243). This association was present for all patients with schizophrenia (N = 56; r = .28, P = .04; r = .35; P = .009; r = .29, P = .03, for neutral, positive and negative valences respectively), but was stronger in NV’s (r = .43, N = 23, P = .04; r = .56, P = .005; r = .50, P = .01, for neutral, positive and negative stimuli).

ERP Responses in the 4 Groups

Table 2 presents the statistical results for N2 and P3 in the different scalp regions. The left-side columns present Cohen’s d values for ERP amplitudes and indicate whether these are significantly different from zero. The right side of the table presents pairwise group comparisons for all groups.

Table 2.

ERP Activation Elicited by Neutral, Negative and Positive Stimuli for Healthy (HC) and Violent (NPV) Controls, Nonviolent (NV) and Violent (VS) Patients Over 5 Scalp Regionsa

| Least Square Means (LSM) for Event-related Component Expressed in Cohen d and P-Values in the 3 Groups | Group Difference LSM for Valence Effect: P-Values | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | HC (N = 28) | NPV (N = 31) | NV (N = 24) | VS (N = 35) | NV | VS | |||||

| HC-NPV | NV-HC | NV-NPV | HC-VS | NPV-VS | NV-VS | ||||||

| Neutral stimuli | |||||||||||

| N2 | Front | −0.84, <.0001*** | −0.77, .0002*** | −0.02, .92 | −0.22, .27 | .88 | .005*** | .009** | .05 | .08 | .44 |

| Cent | −1.02, <.0001*** | −0.77, .0002*** | 0.02, .92 | −0.16, .42 | .43 | .005*** | .006** | .009*** | .05 | .49 | |

| Pari | −0.80, <.0001*** | −0.70, .0006*** | 0.18, .37 | 0.03, .87 | .79 | .001** | .003** | .01** | .02* | .59 | |

| Temp | −1.07, <.0001*** | −0.89, <.0001*** | −0.26, .20 | −0.27, .18 | .60 | .006*** | .02* | .01** | <.05 | .92 | |

| Occi | −0.70, .0007*** | −0.62, .002*** | 0.20, .30 | 0.02, .91 | .86 | .002*** | .005*** | .03* | .04* | .51 | |

| P3 | Front | 0.95, <.0001*** | 0.71, .0006** | 0.93, <.0001*** | 0.59, .004** | .59 | .89 | .51 | .13 | .37 | .10 |

| Cent | 1.40, <.0001*** | 1.01, <.0001*** | 0.94, <.0001*** | 0.79, .0002*** | .35 | .19 | .73 | .01* | .15 | .28 | |

| Pari | 1.59, <.0001*** | 1.07, <.0001*** | 0.98, <.0001*** | 0.87, <.0001 | .17 | .07 | .66 | .004** | .16 | .35 | |

| Temp | 1.15, <.0001*** | 0.79, .0002*** | 0.82, .0001*** | 0.60, .004** | .35 | .34 | .99 | .03* | .24 | .23 | |

| Occi | 1.25, <.0001*** | 0.81, .0001 | 0.76, .0003*** | 0.67, .001** | .23 | .14 | .79 | .02* | .30 | .24 | |

| Negative stimuli | |||||||||||

| N2 | Front | −1.10, <.0001*** | −0.90, <.0001*** | 0.24, .23 | −0.43, .03 | .53 | <.0001*** | .0001*** | .04* | .13 | .01* |

| Cent | −1.32, <.0001*** | −0.98, <.0001*** | 0.12, .56 | −0.63 .002** | .26 | <.0001*** | .0002*** | .04* | .25 | .005* | |

| Pari | −1.11, <.0001*** | −0.97, <.0001*** | 0.12, .55 | −0.51, .01* | .73 | <.0001*** | .0002*** | .07 | .14 | .02* | |

| Temp | −1.41, <.0001*** | −1.12, <.0001*** | −0.29, .15 | −0.69, .0007*** | .37 | .0002*** | .003*** | .03* | .16 | .11 | |

| Occi | −0.84, <.0001*** | −0.84, <.0001*** | 0.11, .58 | −0.47, .02 | .89 | .001** | .001** | .26 | .22 | .03* | |

| P3 | Front | 0.92, <.0001*** | 0.64, .002** | 1.08, <.0001*** | 0.30, .14 | .54 | .38 | .16 | .02* | .13 | .002** |

| Cent | 1.24, <.0001*** | 0.83, <.0001*** | 1.02, <.0001*** | 0.32, .11 | .35 | .68 | .61 | .0007*** | .03 | .005** | |

| Pari | 1.37, <.0001*** | 0.81, <.0001*** | 1.02, <.0001*** | 0.33, .10 | .15 | .92 | .41 | .0002*** | .04 | 005** | |

| Temp | 0.88, <.0001*** | 0.58, .005** | 0.80, .0001*** | 0.19, .34 | .50 | .99 | .52 | .01* | .10 | .02* | |

| Occi | 1.11, <.0001*** | 0.56, .006** | 0.86, <.0001*** | 0.19, .34 | .14 | .59 | .36 | .0009*** | .11 | .0009*** | |

| Positive stimuli | |||||||||||

| N2 | Front | −1.20, <.0001*** | −0.81, <.0001*** | 0.07, .74 | −0.27, .18 | .19 | <.0001*** | .003* | .005*** | .08 | .21 |

| Cent | −1.39, <.0001*** | −0.88, <.0001*** | 0.12, .54 | −0.22, .27 | .08 | <.0001*** | .0006*** | .0004*** | .03* | .20 | |

| Pari | −1.10, <.0001*** | −0.82, <.0001*** | 0.19, .34 | −0.05, .81 | .36 | <.0001*** | .0006*** | .001*** | .01* | .38 | |

| Temp | −1.43, <.0001*** | −1.07, <.0001*** | −0.21, .30 | −0.42, .04 | .24 | <.0001*** | .002** | .002*** | .04* | .40 | |

| Occi | −0.87, <.0001*** | −0.73, <.0001*** | 0.08, .69 | −0.10, .63 | .68 | .001*** | .005*** | .02* | .04* | .51 | |

| P3 | Front | 0.88, <.0001*** | 0.71, .0006*** | 1.13, <.0001*** | 0.69, .001** | .33 | .28 | .18 | .33 | .55 | .04* |

| Cent | 1.25, <.0001*** | 0.90, < .0001*** | 1.14, <.0001*** | 0.77, .0002*** | .25 | .48 | .67 | .07 | .53 | .28 | |

| Pari | 1.46, < .0001*** | 0.85, <.0001*** | 1.12, < .0001*** | 0.72, .0005*** | .08 | .36 | .42 | .004** | .30 | .05 | |

| Temp | 0.92, < .0001*** | 0.51, .01* | 1.00, < .0001*** | 0.44, .03* | .23 | .63 | .11 | .06 | .56 | .02* | |

| Occi | 1.14, < .0001*** | 0.43, .04 | 0.81, .0001*** | 0.52, .01* | .03* | .34 | .21 | .01* | .97 | .15 | |

Note: ERP, Event-Related Potential.

aHierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was used to investigate the group differences.

*P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001. Values highlighted in bold remain significant after the adaptive Hochberg's procedure for correction for multiple testing.

In HC and NPV, N2 and P3 are salient (ie, significantly different from zero) in all scalp regions for all valences, with some increase in N2 and some decrease in P3 as a result of emotional modulation. In both schizophrenic groups, N2 is reduced. It is absent in NV in all scalp areas for all 3 valences. In VS it is absent for neutral and positive valences, but present in all regions for negative valences. P3 is present in all groups for all stimuli, except in VS for negative stimuli where it is absent in all regions.

Pairwise Group Comparisons

N2 is significantly smaller in patients than in HC for all regions and valences. It is also smaller in patients than in NPV except for the NPV-VS differences for the negative valence, where no significant differences were found.

Pairwise P3 differences are not as pronounced. NV’s do not differ significantly from either NPV or HC in any pairwise comparison. VS exhibit reduced P3 and differ from HC for all valences, but much more so for the negative valence. They differ from NPV more rarely, as the latter also exhibit reduced P3.

VS-NV pairwise comparisons indicate no N2 differences for positive and neutral stimuli, but large differences for negative stimuli, as VS present with larger amplitudes than NV in all scalp areas. The opposite is true for P3 with few differences for neutral and positive valences, and many large differences for negative valences, VS presenting with smaller amplitudes than NV in all scalp areas.

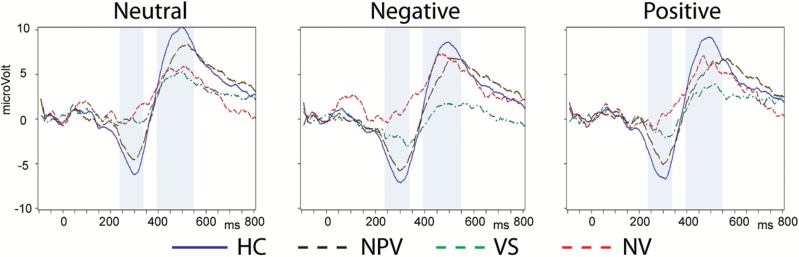

To illustrate these differences, we present (figure 1) grand mean ERP averages indicating ERP responses to neutral and affective stimuli. The shaded areas show the time windows in which N2 and P3 were examined. ERP waveforms were computed across electrodes in the central area, an area in which the differences in the N2/P3 complex are prominent. In the schizophrenic groups, in the neutral condition, N2 and P3 are reduced. In VS, N2 is partially recovered with negative stimuli, and the P3 is most reduced with these stimuli.

Fig. 1.

Grand mean Event-Related Potential (ERP) averages across electrodes in the central area capturing differential ERP responses to affective stimuli (neutral, negative and positive) during the N2 and P3 in healthy controls (N = 28), nonpsychotic violent subjects (N = 31), and in nonviolent (N = 24) and violent (N = 35) patients with schizophrenia.

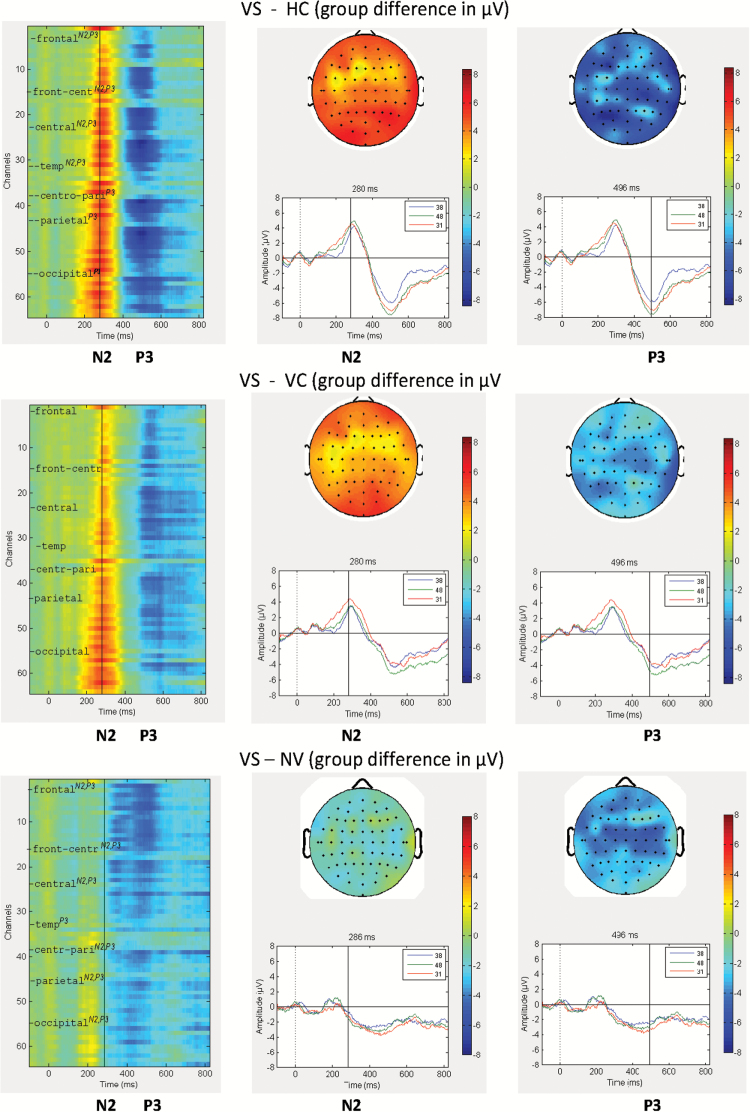

As mentioned above, significant group differences with negative stimuli were detectable across all broad brain regions in the inferential statistical analyses. For a further illustration of this topographical pattern, a graphical summary of the detailed spatio-temporal dynamics of ERPs is provided in figure 2. The figure displays ERP group differences across the entire time course in terms of heatmaps and ERP waveforms, and in terms of topographical distribution for N2 and P3 over the entire scalp. VS show a reduction in N2 and P3 compared to HC and, to a lesser extent, NPV. Compared to NV, VS show larger N2 and smaller P3.

Fig. 2.

Heat maps, topographical distribution, and Event-Related Potential (ERP) waveforms for the group difference in averaged ERPs in response to stimuli with negative valence in violent subjects with schizophrenia (VS) contrasted to Healthy Controls (HC), Nonpsychotic Violent subjects (NPV), and Nonviolent patients (NV). Notes: (1) In each panel (top, middle, bottom), the figures show the heatmap, the topograpical map (ie, voltage distribution in microvolts) over the scalp (at cursor position for N2 and P3), and the ERP curves at Fz, Cz and Pz electrodes. (2) Color coding: Color bars indicate pairwise group differences of grand averages in microvolts. (3) Channels for the topograpical map are ordered from frontal to occipital, with left and right side interleaved. (4) Channel assignments for the heatmap for the broader scalp regions (frontal, fronto-central, central, fronto-temporal, temporal, temporo-parietal, centro-parietal, parietal, parieto-occipital, occipital) are indicated by the tickmarks. Superscripts indicate significant group differences for a given ERP component (N2, P3). (5) Inlets display: ERP group difference waveform for channels Fz (=38), Cz (=48) and Pz (=31), respectively.

Role of Negative Emotional Valence

As mentioned above, N2 increases and P3 decreases in VS are particularly prominent for negative stimuli. We therefore examined further the electrophysiological differentiation between negative and neutral stimuli by computing the difference wave for negatively-valenced stimuli (ERPnegative − ERPneutral) in all 4 groups.

The difference wave was significant in VS only. For N2, it was significant in 3 regions (N = 32): central (Cohen’s d = −0.44, P = .03), parietal (Cohen’s d = −0.55, P = .006), and occipital (Cohen’s d = −0.53, P =.008). It was marginally significant in the temporal area (Cohen’s d = −0.32, P = .06).

For P3, the difference wave was significant in the same 3 regions (N = 32): central (Cohen’s d = −0.48, P = .02), parietal (Cohen’s d = −0.57, P = .005) and occipital (Cohen’s d = −0.47, P = .02). It was marginally significant in the temporal area (Cohen’s d = −0.36, P = .08). In the other 3 groups of subjects there was not a single significant difference wave for either N2 or P3.

Impulsivity and Change in ERP Amplitude With Emotion

We examined how impulsivity traits, a major contributor to impulsive-emotional violence, are related to the changes in ERP amplitude from neutral to negative valences. We investigated the relationship between BIS-11 Total score and the difference wave for N2 and P3 (table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship Between Differential Activation Elicited by Negative vs Neutral Stimuli (ERPnegative − ERPneutral) and the Barratt Impulsiveness-Version 11 (BIS-11) Total Score for the 4 Groups in the 5 Scalp Regionsa

| ERP Component | Scalp-Region | Relationship of ERPnegative − ERPneutral With the BIS-11 Total Score (Spearman ρ) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC (N = 28) | NPV (N = 31) | NV (N = 24) | VS (N = 35) | ||||||

| r | P | r | P | r | P | r | P | ||

| N2 | Frontal | .29 | .12 | .33 | .07 | −.04 | .86 | −.54 | .001** |

| Central | .35 | .06 | .29 | .12 | .01 | .95 | −.55 | .001** | |

| Parietal | .43 | .02* | .27 | .14 | .03 | .90 | −.55 | .001** | |

| Temporal | .27 | .17 | .31 | .09 | .05 | .80 | −.49 | .005** | |

| Occipital | .31 | .11 | .14 | .46 | .006 | .98 | −.57 | <.001** | |

| P3 | Frontal | .25 | .19 | .25 | .17 | −.11 | .62 | −.40 | .02* |

| Central | .19 | .33 | .14 | .44 | −.08 | .70 | −.40 | .02* | |

| Parietal | .17 | .38 | .05 | .78 | −.16 | .46 | −.42* | .01* | |

| Temporal | .13 | .53 | .26 | .16 | −.13 | .55 | −.41 | .02* | |

| Occipital | .06 | .75 | .09 | .62 | −.20 | .34 | −.51 | .003** | |

Note: aSpearman correlation coefficients were used because the distribution was not normal. For N2 a negative correlation indicates larger amplitude (greater negativity); for P3 it means reduced positivity.

*P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01. Values highlighted in bold remain significant after the adaptive Hochberg's procedure for correction for multiple testing.

Table 3 indicates that higher impulsivity is associated with significantly greater N2 enhancement as well as P3 reduction for negative compared to neutral valences in the violent group, in all scalp areas. There was no such association in the other groups.

Supplementary Secondary Analyses

Our main focus in this article was the contrast between the VS and the other groups, but it is possible to consider violence as a dimension across the groups rather than emphasizing group differences. In order to investigate the common neurophysiological mechanism that characterizes violence as a separate dimension independently of psychosis, we classified the groups in an a priori fashion on the basis of presence/absence of violence and presence/absence of psychosis. We investigated the relationship between this categorical classification and measures of N2 and P3 amplitudes in a multivariate way, through canonical correlation analysis, in 4 scalp areas for the stimuli with negative valence. This approach allows us to determine independent dimensions (canonical factors) of the clinical/behavioral variables (violence and psychosis) and to examine their multivariate association with ERP components.

There were 2 significant sets of correlations between these binary variables (ie, the dimensions of psychosis and violence) and the ERP components (supplementary table). The correlation for the first pair, which indexes psychosis, had a P value of <.0001. The correlation for the second pair, which indexes violence, had a P value of .039. These 2 dimensions were independently related to the ERP variables. The loadings of the ERP components on these 2 dimensions are presented in the supplementary table. The first canonical dimension, psychosis, was associated with large N2 reductions in all 4 scalp areas and mild to moderate P3 reductions in the central and parietal areas. The second canonical dimension, violence, is statistically independent of the first and hence the loadings on this dimension contributed by VS reflect only violence with no effect for psychosis. It was associated with P3 reductions in all scalp areas (with moderate to large reductions in the frontal, central and parietal areas) and with mild to moderate “increases” in N2 in the frontal and parietal areas.

Discussion

In order to get a better understanding of violent behavior in patients with schizophrenia, we investigated the neurobiological mechanisms underlying response inhibition and emotional processing, which are associated with violence. The patients in this study present with severe chronic mental illness and it is therefore not surprising that they are more impaired than the nonpsychotic groups on many behavioral and ERP parameters. This included also slower responding to the stimuli for all 3 valences. These differences in reaction time may be related to psychomotor retardation which is common in patients with schizophrenia, although the reaction times in our study were not significantly related to the PANSS Psychomotor Retardation item.

The patients made more commission errors than HC or NPV. There was no VS-NV difference in commission errors, but there was a difference in the reaction time for these errors. VS responded significantly faster than NV on negative stimuli. This fast responding when, in fact, they were required to withhold response, may indicate a failure in inhibition when emotional arousal is present. In NV, these commission errors may reflect a different impairment, ie, a more general cognitive/behavioral deficit. The literature reports that commission errors are associated not only with violence but also with other symptoms, such as negative symptoms.41,42 In our study, these symptoms were more severe in NV than VS (table 1), and commission errors were positively associated with negative symptoms and with deficits in attention, including difficulties shifting focus to new stimuli.

Neurophysiological Differences Among the Groups

There were important neurophysiological group differences. N2 was smaller in both patient groups. It was absent in NVs for all stimuli; in VSs, while it was completely absent with neutral stimuli, it emerged with emotional stimuli, and in particular negative ones, which are known to provoke greater emotional arousal.25 The Emotional Go/NoGo task assesses also emotional reactivity besides response inhibition, and affective valence can independently modulate the N2 component.14 Thus, it would seem that in HC and NPV, N2 reflects primarily cognitive control and may be related to response activation,21 or conflict monitoring22; it was therefore present with neutral stimuli. In the VS, however, it appears to be associated only with emotional reactivity.

As P3 reflects response inhibition,15,16 smaller P3 may indicate lesser neural activation for response inhibition. It was smallest in VS and largest in HC, with intermediate values for NV and NPV. This is consistent with the above literature which reports P3 attenuation in both schizophrenia and impulsive violence.18,19

The effect of negative emotional provocation on P3 amplitude (ie, reduction) was quite pronounced in VS. It may reflect a reduction in response inhibition efficiency, as emotional arousal draws away cognitive resources.43 The electrophysiological differentiation between negative and neutral stimuli (ie, the difference wave) was significant only in VS; furthermore P3 was significantly lower in that group than in NV for negative stimuli in all scalp areas. This deficit may also be reflected in the VS’s faster responding at the expense of accuracy (ie, increased speed when making commission errors), discussed above.

ERPs provide a unique tool to follow the temporal stages for emotional and cognitive processing in violent patients; the emotional arousal (suggested by N2 increase) is followed by impairment in response inhibition (suggested by P3 decrease). This relationship between the 2 ERP components is consistent with the significant correlations obtained between N2 and P3 in the VS group, such that the larger the N2 (ie, “more” negative), the smaller the P3. This relationship was strongest in the frontal region (r = .63, N = 35, P < .001), but was also present in central (r = .39, N = 35, P = .02), temporal (r = .46, N = 35, P = .005), and occipital (r = .34, N = 35, P = .04) regions. There were no significant relationships between N2 and P3 in the other groups.

This time frame could provide an explanation for brain activation findings in imaging studies. It suggests that negative emotions capture attentional resources, at the expense of cognitive processing, probably due to their survival value.12,25,43

In contrast to the hyper-reactive pattern in violent patients, NV were minimally responsive to emotional stimuli, evidencing no significant change in reaction time, in N2 or P3. Their poor task performance is not associated with impulsive/reactive propensities, as is the case with VS, but instead reflects cognitive perseveration and negative symptoms, which also interfere with response inhibition.41,42

These different patterns in the 2 groups can be related to their dissimilar emotional impairments. VS evidenced disturbed emotional reactivity; they presented with more depressive symptoms and these symptoms were related to aggression. NV’s, on the other hand, presented with more severe negative symptoms, including blunted affect. Their lack of emotional reactivity on the Go/NoGo can be seen as part of this particular affective dysfunction, which has been associated with lower levels of violence.44

Impulsive Traits and ERP Changes

Impulsive traits also play a role in the neurophysiological results. Greater impulsivity and reactivity are associated with greater N2 enhancement and greater P3 reduction in VS with negative stimuli. This is consistent with reports of N2 increases in subjects who are more sensitive to emotional provocation.27 There was no significant difference in impulsivity between the 2 patient groups, but our results suggest that it may play a different role in the VS, as it is associated with important ERP changes in that group, when there is negative emotional provocation.

In our study, impulsivity was associated with broadly distributed ERP changes across scalp regions. While the frontal cortex plays a prominent role as the neural substrate of impulsivity, other regions are also involved, such as the inferior parietal cortex,45 posterior cingulate46 and a distributed fronto-temporal network.47 Considering these findings and the fact that volume conduction may lead to widespread scalp distributions, even for sources that predominantly originate from the frontal cortex, we can understand why impulsivity was associated with broadly distributed ERP changes across scalp regions.

Interestingly, the relationship between N2 and the BIS-11 was in the opposite direction for HC’s. As mentioned above, in the HC’s, N2 is associated predominantly with cognitive control processes, such as response activation,21 or conflict monitoring.22 Greater impulsivity is associated with decreased efficiency in these cognitive processes and hence with smaller N2 amplitude.

The 2 Violent Groups: Shared Characteristics

We included the NPV group in order to investigate the effect of psychosis and violence independently from each other. The NPV evidence various disturbances, some of which are shared with the VS, including a history of substance abuse, past psychiatric problems, and childhood/adolescence behavioral problems. They have more severe antisocial behavior and aggression than VS, including reactive-expressive aggressive behaviors, such as temper tantrums, verbal and property aggression. NPV made more commission errors than HC’s. This is consistent with reports of higher number of commission errors in violent populations, mentioned above.

In supplementary analyses, we focused on unique neurophysiological patterns related to violence as a dimension. This dimension is associated with a decrease in P3 and some increase in N2. It is therefore possible that the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie violence in the 2 violent groups are shared to some extent, and that the univariate differences found between these 2 groups are more in degree than in kind.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study included a nonpsychotic violent group which provides a unique opportunity to examine distinct as well as shared neurophysiological characteristics of 2 groups of violent individuals. The use of HLM for ERP data provides a more precise modeling than is usually used in ERP studies. Our study also removed an important confound in the neurophysiological assessment of violent behavior, ie, substance abuse within 6 months of entry in study. Comorbid substance abuse is common in violent patients,48 but may produce its own set of neurophysiological abnormalities.

There were also a number of limitations. This exclusion of subjects with substance abuse restricts the generalizability of our results with regard to dual diagnosis patients. Furthermore, patients in our study had chronic illness, and our results may not apply to acutely psychotic patients. In addition, the current design is cross-sectional; a prospective design which would follow over time people with the deficits defined in our study would provide greater evidence for our model. Future studies using such a design would determine whether these deficits are true pathways to violence.

Conclusions

Some factors have been over-emphasized in research on violence in patients with major mental disorders, such as psychotic symptoms, while other variables, which are often more relevant, have been ignored. In one study of patients with major mental illness,44 psychotic symptoms preceded a violent incident only in a small percentage of cases. The present results support the idea that behavioral disinhibition and emotional dysregulation are important factors for violent behavior. The violent patients evidenced strong reactivity to negative stimuli; this may interfere with response inhibition and lead to impulsive violence. We found further evidence for this interpretation of the ERP changes in the fact that the degree of impulsivity and emotional reactivity in VS are associated with N2 enhancements and P3 reductions when presented with negative stimuli. In contrast, NVs’ decreased emotional reactivity, while clearly abnormal, does not lead to violence, and may even have a protective effect. Our findings provide greater understanding of impulsive-emotional aggression. Recent work in schizophrenia suggests that emotionally based impulsivity is increased in schizophrenia and that this increase is correlated with aggression.49

Our study also considered violence as a dimension independent of psychosis, and found that, to some extent, the ERP patterns which were most prominent in the VS were more generally associated with this dimension.

The neural patterns associated with response inhibition identified in this study may represent altered interactions between a dorsal brain system involved in what has been termed “cold” executive processing and a ventral system involved in “hot” emotional processing.10,49,50 Thus, our findings on the affective disruption of response inhibition provide important insights into the neurobiological underpinning of these altered interactions, and suggest new modes of treatment which would target these specific underlying impairments.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (MH074767).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Witt K, van Dorn R, Fazel S. Risk factors for violence in psychosis: systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 110 studies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krakowski M, Czobor P. Depression and impulsivity as pathways to violence: implications for antiaggressive treatment. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:886–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation–a possible prelude to violence. Science. 2000;289:591–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blair RJ. The roles of orbital frontal cortex in the modulation of antisocial behavior. Brain Cogn. 2004;55:198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berkowitz L. Aggression: Its Causes, Consequences and Control. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kiehl KA, Smith AM, Hare RD, Liddle PF. An event-related potential investigation of response inhibition in schizophrenia and psychopathy. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:210–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lipszyc J, Schachar R. Inhibitory control and psychopathology: a meta-analysis of studies using the stop signal task. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16:1064–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elliott R, Ogilvie A, Rubinsztein JS, Calderon G, Dolan RJ, Sahakian BJ. Abnormal ventral frontal response during performance of an affective go/no go task in patients with mania. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:1163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shafritz KM, Collins SH, Blumberg HP. The interaction of emotional and cognitive neural systems in emotionally guided response inhibition. Neuroimage. 2006;31:468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dolcos F, McCarthy G. Brain systems mediating cognitive interference by emotional distraction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2072–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dolcos F, Miller B, Kragel P, et al. Regional brain differences in the effect of distraction during the delay interval of a working memory task. Brain Res 2007;1152:171–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ramos-Loyo J, González-Garrido AA, García-Aguilar G, Del Río-Portilla Y. The emotional content of faces interferes with inhibitory processing: an event related potential study. Int J Psychol Studies. 2013;5:52–65. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bokura H, Yamaguchi S, Kobayashi S. Electrophysiological correlates for response inhibition in a Go/NoGo task. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:2224–2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Olofsson JK, Nordin S, Sequeira H, Polich J. Affective picture processing: an integrative review of ERP findings. Biol Psychol. 2008;77:247–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Polich J. Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:2128–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bruin KJ, Wijers AA, van Staveren ASJ. Response priming in a go/nogo task: do we have to explain the go/nogo N2 effect in terms of response activation instead of inhibition? Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1660–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Branchey MH, Buydens-Branchey L, Lieber CS. P3 in alcoholics with disordered regulation of aggression. Psychiatry Res. 1988;25:49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gerstle JE, Mathias CW, Standford MS. Auditory P300 and self-reported impulsive aggression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1998;22:575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stanford MS, Greve KW, Mathias CW, Houston RJ. Murderers not guilty by reason of insanity and impulsive aggressive psychiatric outpatients: an EEG/ERP comparison. Psychophys. 1998;35:S79. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Substance use disorders, externalizing psychopathology, and P300 event-related potential amplitude. Int J Psychophysiol. 2003;48:147–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bruin KJ, Wijers AA, van Staveren ASJ. Response priming in a go/nogo task: do we have to explain the go/nogo N2 effect in terms of response activation instead of inhibition? Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1660–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Donkers FCL, van Boxtel GJM. The N2 in go/no-go tasks reflects conflict monitoring not response inhibition. Brain Cogn. 2004;56:165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Olofsson J, Polich J. Affective visual event-related potentials: arousal, repetition, and time-on-task. Biol Psychol. 2007;75:101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carretié L, Hinojosa JA, Martín-Loeches M, Mercado F, Tapia M. Automatic attention to emotional stimuli: neural correlates. Hum Brain Mapp. 2004;22:290–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ohman A, Mineka S. Fears, phobias, and preparedness: toward an evolved module of fear and fear learning. Psychol Rev. 2001;108:483–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. LeDoux JE. Emotion: clues from the brain. Annu Rev Psychol. 1995;46:209–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sehlmeyer C, Konrad C, Zwitserlood P, Arolt V, Falkenstein M, Beste C. ERP indices for response inhibition are related to anxiety-related personality traits. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:2488–2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coccaro EF, Berman ME, Kavoussi RJ. Assessment of life history of aggression: development and psychometric characteristics. Psychiatry Res. 1997;73:147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kay SR, Sevy S. Pyramidical model of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wilkinson GS: Wide-Range Achievement Test 3: Administration Manual. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gladsjo JA, Heaton RK, Palmer BW, Taylor MJ, Jeste DV. Use of oral reading to estimate premorbid intellectual and neuropsychological functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999;5:247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Drevets WC, Raichle ME. Reciprocal suppression of regional cerebral blood flow during emotional versus higher cognitive processes: implications for interactions between emotion and cognition. Cogn Emot. 1998;12:353–385. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. Technical Report A-8. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Delplanque S, N’diaye K, Scherer K, Grandjean D. Spatial frequencies or emotional effects? A systematic measure of spatial frequencies for IAPS pictures by a discrete wavelet analysis. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;165:144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morie KP, De Sanctis P, Garavan H, Foxe JJ. Executive dysfunction and reward dysregulation: a high-density electrical mapping study in cocaine abusers. Neuropharmacology. 2014;85:397–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith JL, Johnstone SJ, Barry RJ. Movement-related potentials in the Go/NoGo task: the P3 reflects both cognitive and motor inhibition. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119:704–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Czobor P, Volavka J. Positive and negative symptoms: is their change related? Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kay S. Positive and Negative Syndromes in Schizophrenia: Assessment and Research. New York, NY: Brunner Mazel, Inc; 1991:243. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ettinger U, Picchioni M, Hall MH, et al. Antisaccade performance in monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia: the Maudsley twin study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:543–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Karoumi B, Ventre-Dominey J, Dalery J. Predictive saccade behavior is enhanced in schizophrenia. Cognition. 1998;68:B81–B91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fenske MJ, Eastwood JD. Modulation of focused attention by faces expressing emotion: evidence from flanker tasks. Emotion. 2003;3:327–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, et al. A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Siever LJ, Buchsbaum MS, New AS, et al. d,l-fenfluramine response in impulsive personality disorder assessed with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. New AS, Hazlett EA, Buchsbaum MS, et al. Blunted prefrontal cortical 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography response to meta-chlorophenylpiperazine in impulsive aggression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:621–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Crews FT, Boettiger CA. Impulsivity, frontal lobes and risk for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Skeem J, Kennealy P, Monahan J, Peterson J, Appelbaum P. Psychosis uncommonly and inconsistently precedes violence among high-risk individuals. Clin Psychol Sci 2016;4:40–49. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hoptman MJ, Antonius D, Mauro CJ, Parker EM, Javitt DC. Cortical thinning, functional connectivity, and mood-related impulsivity in schizophrenia: relationship to aggressive attitudes and behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:939–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mayberg HS. Limbic-cortical dysregulation: a proposed model of depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.