Abstract

Background:

Given the early age of onset (AOO) of psychotic disorders, it has been assumed that psychotic experiences (PEs) would have a similar early AOO. The aims of this study were to describe (a) the AOO distribution of PEs, (b) the projected lifetime risk of PEs, and (c) the associations of PE AOO with selected PE features.

Methods:

Data came from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. A total of 31 261 adult respondents across 18 countries were assessed for lifetime prevalence of PE. Projected lifetime risk (at age 75 years) was estimated using a 2-part actuarial method. AOO distributions were described for the observed and projected estimates. We examined associations of AOO with PE type metric and annualized PE frequency.

Results:

Projected lifetime risk for PEs was 7.8% (SE = 0.3), slightly higher than lifetime prevalence (5.8%, SE = 0.2). The median (interquartile range; IQR) AOO based on projected lifetime estimates was 26 (17–41) years, indicating that PEs commence across a wide age range. The AOO distributions for PEs did not differ by sex. Early AOO was positively associated with number of PE types (F = 14.1, P < .001) but negatively associated with annualized PE frequency rates (F = 8.0, P < .001).

Discussion:

While most people with lifetime PEs have first onsets in adolescence or young adulthood, projected estimates indicate that nearly a quarter of first onsets occur after age 40 years. The extent to which late onset PEs are associated with (a) late onset mental disorders or (b) declining cognitive and/or sensory function need further research.

Key words: epidemiology, psychotic experiences, age of onset, lifetime prevalence, World Mental Health Survey

Introduction

Population-based surveys have provided important new insights into the prevalence of hallucinations and delusions (collectively referred to as psychotic experiences; PEs). A recent cross-national study based on 18 countries reported a lifetime prevalence of PEs of 5.8% (SE = 0.2),1 an estimate comparable to that reported in a recent systematic review.2 Given that psychotic disorders tend to emerge in late adolescence and young adulthood,3 there has been an expectation that PEs would also share an early age of onset (AOO) distribution.2,4

To date, studies have generally reported on the association between age-at-interview and lifetime prevalence of PEs.1,2 To the best of our knowledge, no studies have reported on their AOO. Understanding the AOO of PEs is important for 2 reasons. First, AOO distributions can be used to estimate lifetime morbid risk (ie, projected estimate of the proportion of the population who will develop PE during of their lifetime).5 Lifetime prevalence estimates the proportion of the population who have experienced a PE up to the age at interview. In contrast, projected lifetime risk estimates the proportion of the population who will have PEs throughout their lifetime.

Lifetime risk cannot be estimated directly from community surveys because respondents in surveys differ in age and, therefore, in number of years of expected future risk. The projected estimates can also be used to define standardized AOO percentiles, which provide a more valid indication of the age range during which PEs would be expected to first occur. These estimates are more informative for service planning. Second, an accurate understanding of the AOO distribution is required to design studies of antecedent predictors of PE onset, thus disentangling causal pathways from consequences (eg, temporally secondary symptoms or disorders). We had the opportunity to examine the AOO distribution of PEs in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. The objectives of the present study were to describe (a) the projected lifetime risk of PEs, (b) the observed and projected AOO distributions, and (c) the association between PE-related metrics and AOO.

Methods

Samples

The WMH surveys are a coordinated set of community surveys administered in probability samples of the household population in countries throughout the world (www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/WMH).6 Eighteen of the 29 WMH surveys administered the CIDI Psychosis Module. These 18 countries are distributed across North and South America (Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Sao Paulo in Brazil, United States); Africa (Nigeria); the Middle East (Iraq, Lebanon); Asia (Shenzhen in the People’s Republic of China); the South Pacific (New Zealand); and Europe (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Spain). All the surveys were based on multi-stage, clustered area probability household sampling designs (supplementary table S1). A total of 31 401 respondents in these surveys were evaluated for PEs. The weighted average response rate across the surveys was 72.1%. Data were grouped for purposes of analysis into 3 country-level income strata according to the World Bank classification of low, middle, and high income countries.7

In keeping with previous studies of PEs,1,4,8–10 we made the a priori decision to exclude individuals who had PEs and also screened positive for possible schizophrenia/psychosis or manic-depression/mania (ie, respondents who (a) reported (1) schizophrenia/ psychosis or (2) manic-depression/mania in response to the question “What did the doctor say was causing (this/these) experiences?”; and/or (b) those who ever took any antipsychotic medications for these symptoms). This resulted in the exclusion of 140 respondents (0.4% of all respondents), leaving 31 261 respondents for this study (supplementary table S1).

Procedures

All surveys were conducted face-to-face by trained lay interviewers in the respondents’ homes. Informed consent was obtained before beginning interviews in all countries. Procedures for obtaining informed consent, and ethical approvals were monitored for compliance by the institutional review boards of the collaborating organizations in each country.11 Standardized interviewer training and quality control procedures were used consistently in the surveys. Full details of these procedures are described elsewhere.12,13

All WMH interviews had 2 parts. Part I, administered to all respondents, contained assessments related to core mental disorders. Part II included additional information relevant to a wide range of survey aims, including assessment of PEs. All Part I respondents who met criteria for any DSM IV mental disorder, as well as a probability sample of other respondents were administered Part II. Within the different sites, items related to PEs were either administered to all Part II respondents or a random sample of Part II respondents. Part II respondents were weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection into Part II to adjust for differential sampling. For example, if only 25% of non-cases from Part 1 were administered Part II, we gave each of these respondents a weight of 1/0.25 = 4, so that the undersampled subset that progresses to Part II were weighted to represent the original set. Because all of the cases progress to Part II (100% sampling), then respondent in this set each have a weighting of only 1/1 = 1. Additional weights were used to adjust for differential probabilities of selection within households, nonresponse, and to match the samples to population sociodemographic distributions. Thus, the weighted estimates shown below are representative of the original sampling frame. Further details of the construction of the analyses weights are provided elsewhere.12

Data Collection and Data Items.

The instrument used in the WMH surveys was the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI),14 a validated fully-structured diagnostic interview (http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi/instruments_download.php) designed to assess the prevalence and correlates of a wide range of mental disorders according to the definitions and criteria of both the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic systems. WHO translation, back-translation, and harmonization protocols were used to adapt the CIDI for use in each participating country.15

Psychotic Experiences.

The CIDI Psychosis Module included questions about 6 PE types—2 related to hallucinatory experiences (HEs; visual hallucinations, auditory hallucinations) and 4 related to delusional experiences (DEs; thought insertion/withdrawal, mind control/passivity, ideas of reference, plot to harm/follow; supplementary tables S2a and S2b). The module began by asking respondents if they ever experienced the PEs (eg, “Have you ever seen something that wasn’t there that other people could not see?”; “Have you ever heard any voices that other people said did not exist?” etc.). Respondents were also asked to confirm if the reported PEs ever occurred when the person was “not dreaming, not half-asleep, or not under the influence of alcohol or drugs” (the wording of this component of the PE screen differed slightly between 2 versions of the CIDI—see supplementary tables S2a and S2b). Only responses of the latter type are considered here. Respondents who reported PEs were then asked several probe questions about: (a) frequency of the PEs in their lifetime, and (b) the AOO of PEs (ie, How old were you the very first time [this/either of these things/any of these things] happened to you?). In the 8.0% of cases where PE AOO was missing, we used imputation to assign predicted values based on a set of predictors that included all the variables in the substantive model.14 Key summary statistics (n, mean, SE, median, interquartile range [IQR]) for the observed data (without imputation) and the entire dataset after imputation are shown in supplementary table S3. In order to explore possible differences in the AOO of PE types (eg, do HEs typically precede DEs?), we present AOO estimates for any PE, any HE (with or without DEs), any DE (with or without HEs), “pure” HE (without DEs), and “pure” DE (without HEs).

Statistical Analysis

In a previous publication,1 we described 2 PE-related metrics used to characterize PEs in the WMH data—the Type metric and Frequency metric. The Type metric reports on the count of different types of PEs experienced by respondents (exactly 1 type, exactly 2 types, 3 or more types). The Frequency metric reported the cumulative lifetime number of PE episodes. For the current analyses, we also derived an “Annualized PE Frequency Rate,” by dividing the cumulative total number of PEs between onset and age at interview by the number of years since onset. In order to avoid zero values in the denominator of the new rate (eg, in those with onsets at the same age as when interviewed), we added 1 to the years-since-onset value. We examined PE AOO when stratified according to (a) PE type metrics and (b) annualized frequency rate (divided into tertiles).

Proc LIFETEST in SAS was used to generate the AOO distributions of PE and undertake related comparisons. Time-to-event analysis of AOO took into account right-censored observations; thus graphical displays and related analyses based on Proc LIFETEST may be right shifted (ie, later AOO) compared to analyses based on observed data. Projected lifetime risk as of age 75 years was estimated using the actuarial method.16 This method assumes a constant conditional risk of onset during a given year of life across age cohorts and allows for accurate estimations of the onset timings within a year. As the WMH data are both clustered and weighted, the design-based Taylor series linearization17 implemented in version 11 of the SUDAAN software system software18 was used to estimate means, IQR ranges of AOO distributions, and SEs and to evaluate statistical significance. Tests of significance were evaluated using F tests or Wald Chi-square tests based on design-corrected coefficient variance–covariance matrices. Statistical significance was evaluated consistently using 2-tailed 0.05-level tests.

Results

Estimated lifetime prevalence and lifetime projected risks for PEs and related subtypes are shown in table 1. For PEs, HEs, DEs, pure HEs and pure DEs, the projected lifetime risks (SEs) were 7.8% (0.3), 6.8% (0.3), 1.9% (0.1), 5.9% (0.3) and 1.0% (0.1), respectively. These projected estimates were 31%–46% higher than the comparable lifetime prevalence estimates for the different PE types. The means (SEs) for the observed AOO and selected quantiles (including median and IQR) for projected AOO for key PE types are also shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence, Projected Risk at Age 75 Years, Mean and SE of the Observed Age of Onset, and Percentiles of the Projected Age of Onset Distributions of Psychotic Experiences (PEs)

| Prevalence | Projected Risk at Age 75 | Observed Age of Onset | Ages at Selected Percentiles of Projected Age of Onset Distributions | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n a | %b | SE | % | SE | Mean | SE | 10 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 90 | 99 | |

| I. PE type | |||||||||||||

| Lifetime psychotic experiences | 2385 | 5.8 | 0.2 | 7.8 | 0.3 | 24.4 | 0.5 | 10 | 17 | 26 | 41 | 52 | 62 |

| Lifetime hallucinatory experiences | 2078 | 5.2 | 0.2 | 6.8 | 0.3 | 24.0 | 0.6 | 9 | 16 | 25 | 40 | 50 | 62 |

| Lifetime delusional experiences | 658 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 24.5 | 1.0 | 11 | 18 | 27 | 45 | 54 | 61 |

| Lifetime pure hallucinatory experiences | 1727 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 5.9 | 0.3 | 24.3 | 0.6 | 9 | 16 | 26 | 40 | 50 | 62 |

| Lifetime pure delusional experiences | 307 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 26.9 | 1.3 | 14 | 20 | 30 | 45 | 54 | 61 |

| II. PE type metricsc,d | |||||||||||||

| Exactly 1 type | 1631 | 4.2 | 0.2 | 5.7 | 0.3 | 25.0 | 0.6 | 11 | 17 | 26 | 40 | 52 | 65 |

| Exactly 2 types | 544 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 23.8 | 1.2 | 11 | 15 | 26 | 42 | 48 | 61 |

| 3 or more types | 210 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 18.7 | 1.2 | 6 | 9 | 18 | 24 | 58 | 58 |

Note: aCounts were based on unweighted data.

bEstimates were based on weighted data.

cType of PE: visual, auditory, thought insertion/withdrawal, mind control/passivity, ideas of reference, plot to harm/follow.

dBivariate linear regression to test for significant differences in means of observed age of onset between PE type metrics, adjusted for country. Overall F test = 14.1, P < .001. Pairwise comparison between exactly 1 and 2 types (F = 1.5, P = .129); between exactly 1 and 3 types (F = 5.3, P < .001); between exactly 2 and 3 types (F = 3.3, P = .001). Significant level for all pairwise comparisons is being set at the .01 level.

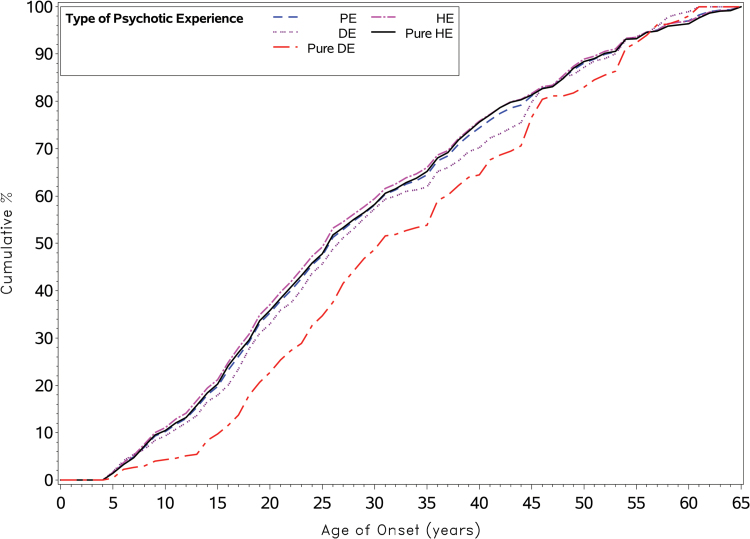

Figure 1 shows the cumulative AOO distributions of PE and related subtypes based on projected data for the various PE subgroups, including those with PEs, pure HEs, DEs, and pure DEs. A key feature that emerges from these distributions relates to the delayed AOO for those with pure DE. Those with pure HE have an earlier AOO distribution, and PE types that contain any HEs also share comparable (closely overlapping) distributions. The AOO for pure HEs was significantly earlier than that for pure DEs (, P < .001). The cumulative distributions have a linear (vs sigmoidal) pattern. Based on the standardized AOO (table 1), the age range encompassed by the IQR (25th–75th percentiles) for PEs was 17 to 41 years (a range of 24 years). Similar patterns were found for the PE subgroups (IQR gap ranged from 24 to 27 years for pure HEs to DEs, respectively). The AOO distributions for PEs, DEs and HEs did not differ by sex (supplementary table S4).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative distribution of projected age of onset by Psychotic Experience type (truncated at age 65 years).

Table 1 also shows mean (SE) and median (IQR) for AOO distributions of lifetime PEs when stratified by the PE type metric. The AOO was monotonically lower in those reporting more PE types (mean AOOs were 25.0, 23.8, 18.7 years for exactly 1 type, exactly 2 types, and 3 or more types, respectively (F = 14.1, P < .001).

The annualized frequency rate by type of PE (and count) is provided in supplementary table S5. Table 2 shows AOO distributions when stratified by tertiles of annualized frequency rates. Those with higher annualized frequency rates had later AOO (mean AOOs for lowest, middle, and highest tertiles were 21.6, 25.5, and 26.1 years, respectively; F = 8.0, P < .001).

Table 2.

Mean and Interquartile Range (IQR) of Age of Onset Distribution of Psychotic Experiences (PEs) by Annualized PE Frequency Metric (n = 2385)

| Tertiles of Frequency of PE per Yeara | n b | Meanc | SE | Median (IQR) | F Testd | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest tertile (≤0.1 episodes per year) | 786 | 21.6 | 0.8 | 18 (10–28) | 8.0 | <.001 |

| Middle tertile (0.1 to 0.8 episodes per year) | 763 | 25.5 | 1.1 | 21 (14–34) | ||

| Highest tertile (>0.8 episodes per year) | 836 | 26.1 | 0.8 | 22 (15–35) |

Note: aAnnualized PE (Frequency of PE per year) = Frequency of PE/ (age at interview − age of onset + 1).

bUnweighted number of respondents.

cEstimates were based on weighted data.

dBivariate linear regression to test for significant differences in means of age of onset, adjusted for country. Overall F test = 8.0, P < .001. Pairwise comparison between the lowest and middle tertile (F = 2.9, P = .004); between the lowest and highest tertile (F = 3.8, P < .001); between the middle and highest tertile (F = 0.0, P = .99). Significant level for all pairwise comparisons is being set at the .01 level.

We also examined AOO in the 140 individuals who were screen positive for a psychotic disorder (ie, who were excluded from the main analyses). For this group the mean (SE) AOO was 25.9 (1.1) years, and the median (IQR) was 23 (18–33) years. The comparable values for the main PE analyses (n = 2385) were mean (SE) = 24.4 (0.5), and median (IQR) = 26 (17–41). The 2 distributions were not significantly different (t = 0.7, P = 0.41).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to present the AOO distributions for PEs. Based on projected AOO values, the median AOO for PEs was 26 years, with a 24-year interval between the 25th and 75th percentiles. There is a lack of comparable standardized AOO estimates for schizophrenia although the Northern Finnish Birth Cohort reported that the median (IQR) AOO for schizophrenia was 23 (19–27) years.19 Thus, while PEs have a comparable median onset in the 20s, the onset of schizophrenia is concentrated in a narrower age range compared to PEs. The IQR difference is 8 years for schizophrenia vs 24 years for PEs. Strikingly, approximately a quarter of individuals who will experience PEs during their life will have their first experience after age 40 years.

In contrast to the AOO of schizophrenia3 we found no sex difference in the AOO of PEs (nor in HEs and DEs). The projected lifetime risk for PEs was 7.8% (SE = 0.3), indicating that approximately 1 in 13 people can expect to have at least 1 PE by the age 75 years. The projected risk is 34% higher than the lifetime risk (5.8%, SE = 0.2). This finding is broadly consistent with the estimates of projected lifetime risk of DSM-IV disorders in the WMH surveys, which were also approximately one-third higher (IQR 28%–44%) than estimated lifetime prevalence estimates.20 In addition, based on the difference between projected and lifetime risks, it is feasible to generate population-based estimates related to the future risk of PEs (eg, 3 people are likely to experience the first onset of PEs at some time in the future for every 10 people who have already experienced PEs). Projected lifetime estimates of PEs may be of use to researchers interested in identifying individuals at high risk of psychotic disorders.21

Because early work in this field concentrated on PEs as predictors of later psychosis,22–24 and because psychosis has a modal AOO in the early 20s,3 later PE onsets has not previously been a topic of interest. We have recently reported on the bi-directional relationship between PEs and key mental disorders assessed within the World Mental Health Survey.25 While the association between PEs and an increased risk of subsequent psychosis has been well recognized,26 we found that a wide range of mental disorders predicted the later first onset of PEs (18 of 21 primary mental disorders). Several of the mental disorders associated with the later onset of PEs tend to have a wide AOO.20 These include mood disorders (median and IQR AOO; 30, 18–43 years), generalized anxiety disorder (31, 20–47 years) and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (23, 15–39 years). While we cannot discount the impact of age-related differential recall (leading to older individuals forgetting early life PEs resulting in older AOO), we speculate that later onset PEs (eg, after age 40 years) may arise as a consequence of temporally primary mental disorders. We plan to explore if the temporal order and lag between mental disorders and PEs varies across the age range, and also compare early vs late AOO according to sociodemographic and clinical factors.

Apart from disorders with peak onsets in young adulthood, hallucinations and delusions can also be features of dementia and aging-related sensory impairments.27 Furthermore, there are links between cognitive capacity and proneness to PEs.28,29 We speculate that age-related cognitive decline may contribute to the emergence of PE in later life (eg, a “release” phenomenon associated within diminishing cognitive capacity). Prospective studies would be better able to explore the associations between late-onset PEs and age-related cognitive decline and/or aging-related sensory impairments.

We found that the AOO for HEs was significantly earlier than for DEs. As noted previously,1 studies that report on PEs as a broad class will miss subtle nuances in the epidemiological profile of HEs and DEs. Previously, we found that the lifetime prevalence of HEs were substantially higher than DEs (5.2% vs 1.3%, respectively). Here we report an additional epidemiological feature that differentiates HEs and DEs. The AOOs for pure HEs are left-shifted (ie, earlier) compared to pure DEs. Smeets and colleagues30,31 have previously proposed that delusional misinterpretations of prior hallucinations may characterize the progression of phenomenology in emerging psychosis. Furthermore, in future studies we will explore if preceding substance use may differentially “bring forward” the AOO of HEs vs DEs.

With respect to PE metrics, we found that those with more PE types had an earlier AOO. This finding may indicate that among those with lifetime PEs, individuals with a more severe phenotype (eg, more types of HEs and/or DEs) tend to have an earlier AOO. Curiously, when we analyzed AOO distributions according to the annualized PE frequency rate, we found a different pattern. Those with higher frequency rates tended to have later onsets, which suggests that factors related to (a) the mix of PE types, and (b) PE annualized frequency rate, may vary across the lifespan. This study provides the first report of the annualized PE rate. While this measure makes the simplifying assumption that PE episodes are evenly spaced across the years since onset, it provides a more valid metric for comparing PE frequency rates across groups with different PE AOO and age at interview. Describing the AOO of PEs alongside type and frequency metrics allows us to build a more nuanced understanding of how PEs relate to mental disorders across the lifespan. In particular, these metrics may provide an empirical framework to better understand shared and discrete features of PEs and clinical psychotic disorders.

While the current study has many strengths (eg, large sample size, range of countries, uniform methodology for data collection), it also has several important limitations. We relied on lay interviewers to administer the questionnaire. Different instruments will detect different PEs prevalence estimates, and the brief CIDI items may underestimate the true lifetime prevalence of PEs. Moreover, we did not have access to clinical validations of psychotic disorders, although we excluded individuals who screened positive for psychosis. Most importantly, we relied on retrospective reports about AOO. The latter might have led to recall bias despite the use of special AOO probes in the CIDI that have been shown to improve the accuracy of retrospective AOO reporting.32 In addition, age-related recall bias can impact on projected life time risk (eg, if older respondents differentially forget earlier PEs, then this will result in higher projected lifetime estimates). Large prospective surveys with repeated assessment of PE-related metric will be needed to address these issues.

Conclusions

Based on responses to the CIDI, approximately 1 in 13 people can expect to have at least 1 PE by age 75 years. While the median AOO for PEs is comparable to the AOO for schizophrenia (ie, early 20s), the AOO distribution is wider, with approximately a quarter of individuals having their first PE at or after age 40 years. Earlier AOO is associated with a higher PE type metric, and a lower PE annualized frequency rate. A better understanding of how PEs unfold across the lifespan and interact with mental disorders may help contextualize the epidemiologic landscape of PEs.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

Each World Mental Health (WMH) country obtained funding for its own survey. The Sao Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey is supported by Thematic Project Grant 03/00 204-3 from the State of Sao Paulo Research Foundation; the Shenzhen Mental Health Survey, by the Shenzhen Bureau of Health and the Shenzhen Bureau of Science, Technology, and Information; the Colombian National Study of Mental Health, by the Ministry of Social Protection and the Saldarriaga Concha Foundation; the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders project, by contracts QLG5-1999-01042 and 2004123 from the European Commission, the Fondo de Investigacion Sanitaria (the Piedmont Region [Italy]), grant FIS 00/0028 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spain), grant SAF 2000-158-CE from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnologia (Spain), grants Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red CB06/02/0046 and Redes Tematicas de Investigacion Cooperativa en Salud RD06/0011 REM-TAP from the Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, other local agencies, and an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline; the Iraq Mental Health Survey (IMHS), by funding from the Japanese and European funds through United Nations Development Group Iraq Trust Fund; the Lebanese National Mental Health Survey, by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the World Health Organization (WHO) (Lebanon), anonymous private donations to the Institute for Development, Research, Advocacy and Applied Care, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from Janssen Cilag, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Novartis; the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS), by grant INPRFMDIES 4280 from The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente, grant CONACyT-G30544-H from the National Council on Science and Technology, and supplemental support from the Pan American Health Organization; the New Zealand Mental Health Survey, by the New Zealand Ministry of Health, Alcohol Advisory Council, and the Health Research Council; the Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Well-being, by the WHO (Geneva), the WHO (Nigeria), and the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja; the Peruvian World Mental Health Study, by the National Institute of Health of the Ministry of Health of Peru; and the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication, by grant U01-MH60220 from the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, grant 044708 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the John W. Alden Trust.

The Portuguese Mental Health Study was carried out by the Department of Mental Health, Faculty of Medical Sciences, NOVA University of Lisbon, with the collaboration of the Portuguese Catholic University, and was funded by the Champalimaud Foundation, the Gulbenkian Foundation, the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and the Ministry of Health.

The Romania WMH study projects “Policies in Mental Health Area” and “National Study regarding Mental Health and Services Use” were carried out by the National School of Public Health and Health Services Management (former the National Institute for Research and Development in Health, present National School of Public Health Management and Professional Development, Bucharest), with technical support from Metro Media Transylvania, the National Institute of Statistics—National Center for Training in Statistics, Cheyenne Services SRL, Statistics Netherlands and were funded by the Ministry of Public Health (formerly the Ministry of Health) with supplemental support from Eli Lilly Romania SRL.

The surveys discussed in this article were administered in conjunction with the WHO WMH Survey Initiative. The WMH staff assisted with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis, and these activities were supported by grant R01MH070884 from the US National Institute of Mental Health, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, grants R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558 from the US Public Health Service, Fogarty International Research Collaboration award R01-TW006481 from the Fogarty International Center, the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views or policies of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the WHO. During the past 3 years, R.C.K. has been a consultant for Hoffman-La Roche, Inc, Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, and Sanofi and has served on advisory boards for Mensante Corporation, Plus One Health Management, Lake Nona Institute, and US Preventive Medicine. No other disclosures were reported. E.J.B. has funding from CDC/NIOSH (U01OH010712; R. Kotov; PI; U01OH010718, B. Luft, PI; and U01OH010718, A. Gonzalez, PI) and NIA (R01AG049953, S. Clouston, PI). J.J.M. received John Cade Fellowship APP1056929 from the National Health and Medical Research Council. All other authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Psychotic experiences in the general population: a cross-national analysis based on 31,261 respondents from 18 countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Linscott RJ, van Os J. An updated and conservative systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence on psychotic experiences in children and adults: on the pathway from proneness to persistence to dimensional expression across mental disorders. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1133–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thorup A, Waltoft BL, Pedersen CB, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M. Young males have a higher risk of developing schizophrenia: a Danish register study. Psychol Med. 2007;37:479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scott J, Welham J, Martin G, et al. Demographic correlates of psychotic-like experiences in young Australian adults. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustün TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Bank. World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saha S, Scott JG, Johnston AK, et al. The association between delusional-like experiences and suicidal thoughts and behaviour. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saha S, Scott JG, Varghese D, Degenhardt L, Slade T, McGrath JJ. The association between delusional-like experiences, and tobacco, alcohol or cannabis use: a nationwide population-based survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Varghese D, Scott J, Welham J, et al. Psychotic-like experiences in major depression and anxiety disorders: a population-based survey in young adults. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:389–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heeringa SG, Wells JR, Hubbard F, et al. Sample designs and sampling procedures. In: Kessler RC, Üstün TB, eds. The WHO World Mental Health Survey: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:14–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pennell B, Mneimneh ZN, Bowers A, et al. Implementation of the World Mental Health Surveys. In: Kessler RC, Üstün TB, eds. The WHO World Mental Health Survey: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:33–57. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview. In: Kessler RC, Üstün TB, eds. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:58–90. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harkness J, Pennell B, Villar A, Gebler N, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Bilgen I. Translation procedures and translation assessment in the World Mental Health Survey initiative. In: Kessler RC, Üstün TB, eds. The WHO World Mental Health Survey: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:91–113. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Halli SS, Rao VK. Advanced Techniques of Population Analysis. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 18. SUDAAN: Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data [Computer Program] Version. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lauronen E, Miettunen J, Veijola J, Karhu M, Jones PB, Isohanni M. Outcome and its predictors in schizophrenia within the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:168–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fusar-Poli P, Schultze-Lutter F, Cappucciati M, et al. The dark side of the moon: meta-analytical impact of recruitment strategies on risk enrichment in the clinical high risk state for psychosis. Schizophr Bull. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hanssen M, Bak M, Bijl R, Vollebergh W, van Os J. The incidence and outcome of subclinical psychotic experiences in the general population. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44:181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Poulton R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, Murray R, Harrington H. Children’s self-reported psychotic symptoms and adult schizophreniform disorder: a 15-year longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1053–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Werbeloff N, Drukker M, Dohrenwend BP, et al. Self-reported attenuated psychotic symptoms as forerunners of severe mental disorders later in life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. The bi-directional associations between psychotic experiences and DSM-IV mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaymaz N, Drukker M, Lieb R, et al. Do subthreshold psychotic experiences predict clinical outcomes in unselected non-help-seeking population-based samples? A systematic review and meta-analysis, enriched with new results. Psychol Med. 2012;42:2239–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Borsje P, Wetzels RB, Lucassen PL, Pot AM, Koopmans RT. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in community-dwelling patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:385–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khandaker GM, Stochl J, Zammit S, Lewis G, Jones PB. A population-based longitudinal study of childhood neurodevelopmental disorders, IQ and subsequent risk of psychotic experiences in adolescence. Psychol Med. 2014;44:3229–3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barnett JH, McDougall F, Xu MK, Croudace TJ, Richards M, Jones PB. Childhood cognitive function and adult psychopathology: associations with psychotic and non-psychotic symptoms in the general population. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smeets F, Lataster T, van Winkel R, de Graaf R, Ten Have M, van Os J. Testing the hypothesis that psychotic illness begins when subthreshold hallucinations combine with delusional ideation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127:34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smeets F, Lataster T, Dominguez MD, et al. Evidence that onset of psychosis in the population reflects early hallucinatory experiences that through environmental risks and affective dysregulation become complicated by delusions. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:531–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Knäuper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC. Improving accuracy of major depression age-of-onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Method Psychiatr Res. 1999;8:39–48. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.