Abstract

Propeptides of proprotein convertases regulate activation of their protease domains by sensing the organellar pH within the secretory pathway. Earlier experimental work highlighted the importance of a conserved histidine residue within the propeptide of a widely studied member, furin. A subsequent evolutionary analysis found an increase in histidine content within propeptides of secreted eukaryotic proteases compared with their prokaryotic orthologs. However, furin activates in the trans-golgi network at a pH of 6.5 while a paralog, proprotein convertase 1/3, activates in secretory vesicles at a pH of 5.5. It is unclear how a conserved histidine can mediate activation at two different pH values. In this manuscript, we measured the pKa values of histidines within the propeptides of furin and proprotein convertase 1/3 using a histidine hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry approach. The high density of histidine residues combined with an abundance of basic residues provided challenges for generation of peptide ions with unique histidine residues, which were overcome by employing ETD fragmentation. During this analysis, we found slow hydrogen–deuterium exchange in residues other than histidine at basic pH. Finally, we demonstrate that the pKa of the conserved histidine in proprotein convertase 1/3 is acid-shifted compared with furin and is consistent with its lower pH of activation.

Graphical abstract

The addition or removal of a proton represents the smallest possible chemical alteration of a protein, but it can change the charge by one unit and alter the status of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors.1 Changes in cellular proton concentrations (pH) can therefore induce rapid reversible chemical modifications by shifting the equilibrium of titratable amino acid side chains between their unprotonated and protonated forms, thus perturbing the electrostatic potential to drive changes in protein structure, dynamics, and interactions. Hence, there is significant interest in experimentally measuring equilibrium constants (pKa’s) for protonation/deprotonation of specific amino acid residues within a protein.2

Histidine is a unique amino acid because the pKa of its imidazole side chain is close to physiological pH, thus positioning the side chain as a charge relay system within the catalytic sites of proteins and as a sensor that recognizes subtle perturbations in local pH.3 The slow hydrogen–deuterium (HD) exchange within the imidazole ring of histidine residues can be exploited to assess the local pKa of histidine residues.4 In proteins, the C2 hydrogen in imidazole rings can be exchanged with deuterium with a half-life of days, which is substantially slower than hydrogen bound to oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur atoms. Therefore, by incubating a protein in deuterated buffer for several days, followed by a shorter incubation (~30 min) in hydrogen-containing buffer, one can selectively label the imidazole ring with deuterium. This uptake can then be quantified with mass spectrometry. Because the exchange rate depends on the protonation state of the histidine residue, one can determine histidine pKa’s by performing this experiment at different pH values. This method has been successfully used to determine the pKa of individual histidine residues in RNase A4 and dihydrofolate reductase5 and helped to probe the mechanism by which long-range interactions can stabilize the formation of a complex between anthrax protective antigen and its receptor capillary morphogenesis protein-2.6

Proprotein convertases (PCs) take inactive proteins and peptides and, via endoproteolytic cleavage, produce active hormones, enzymes, and other critical components of the cellular machinery along the secretory pathway, in the extracellular matrix, and at the cell surface.7 The PC family includes nine members: furin, PC1/3, PC2, PC4, PACE4, PC5/PC6, PC7/LPC/PC8, SKI/S1P, and NARC-1/PCSK9, all of which are initially synthesized as proproteins at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and undergo folding and primary cleavage in the ER lumen. Final activation requires a second cleavage within the propeptide, which occurs only after the propeptide/PC complex traffics into the correct organellar compartment.8

Organellar pH seems to be the major biochemical cue that triggers the final activation step of PCs because individual paralogs display differences in their pH-dependent activation. For example, furin activates at pH 6.5, the pH of the early trans-golgi network (TGN),9 whereas PC1/3, a neuroendocrine-specific PC activates at pH 5.5, the pH of mature, dense-core, secretory granules.10 Swapping propeptides between furin and PC1/3 switches their sensitivity to pH-dependent activation, demonstrating that the pH sensor, which recognizes organellar pH and regulates protease activation, is localized within the propeptide.11 Studies identify histidine 69 (His69) as the pH sensor in the furin propeptide (PROFUR) because its substitution with a leucine blocks pH-mediated activation12 through a local conformational change.13

Although the pH sensor in furin has been identified,12 several important questions about the mechanism of pH-mediated activation of PCs remain unanswered. For example, the residue corresponding to His69 in PROFUR is conserved in the propeptide of PC1/3 (PROPC1). Nevertheless, PC1/3 requires a 10-fold higher proton concentration for its activation when compared with furin, suggesting that additional factors are critical for fine-tuning pH sensitivities of individual PC paralogs. In this study, we address these important mechanistic questions about the pH-mediated activation of PCs by measuring the histidine pKa values in PROFUR and PROPC1 using hydrogen–deuterium (HD) exchange mass spectrometry. The high density of histidines and positively charged residues in these propeptides provides challenges for proteolytic separation, which we overcome by combining the use of electron-transfer dissociation (ETD), collision-induced dissociation (CID), and proteolysis using pepsin. Analysis of this data demonstrated a thus far unappreciated slow-dynamic HD exchange in residues other than histidine, which may provide an approach to probe the local environment of additional amino acid residues. We find that His72 in PROPC1, which corresponds to the established His69 pH sensor of PROFUR, has an acid-shifted pKa of ~5.6, a value that is consistent with its pH for activation. These results now provide a chemical basis for how PROFUR controls activation of its cognate catalytic domain at the more neutral pH in the TGN (pH~ 6.5) when compared with PROPC1, which requires a more acidic pH for activation of the catalytic domain of PC1/3 in the dense-core secretory granules (pH ~ 5.5).

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Purification of Propeptides

PROFUR and PROPC1 were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21/DE3 and purified by ion-exchange chromatography in 5 M urea. After purification, proteins were concentrated and stored in 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride. Before experiments were performed, the proteins were refolded by dialyzing twice against a 100× volume of 50 mM Tris pH 7.4/50 mM NaCl. After refolding, the protein was centrifuged for 30 min at 100000g to remove aggregates, and the concentration was determined by the absorption at 280 nm. Point mutations in PROFUR were generated using the Quikchange protocol and purified via a process identical to that for wild-type PROFUR.

HD Exchange

D2O buffers contained 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 3.5–4.5), 50 mM MES (pH 5.0–7.5), and 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0–9.0). The pH was adjusted using DCl or NaOD, with a pH electrode calibrated with standard buffer solution without correcting for the isotope effect, as in previous studies.4,5 Conductivity was adjusted with sodium chloride to match a 50 mM MES/50 mM NaCl buffer at pH 5.0. About 20 µg of propeptides was diluted 1:50 into 100 µL of deuterium buffer. A control sample was diluted into the same amount of H2O buffer. The samples were kept at 37 °C for 72 h. After this incubation, the exchange was quenched by addition of 10 µL of formic acid, and the samples were dried using a SpeedVac. For pepsin digestion, the sample was resuspended in 20 µL of potassium phosphate buffer at pH 2.3 containing 0.4 µg of pepsin. After a 30 min digest at 37 °C, the samples were dried again and resuspended in 50 µL of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature to allow for back-exchange of polar hydrogens. Samples for whole-protein ETD analysis were directly resuspended in ammonium bicarbonate and allowed to back-exchange for 30 min. After drying in a SpeedVac, the samples were stored at −80 °C until measurement.

Mass Analysis

Mass analysis was performed using an Orbitrap Fusion instrument (Thermo Scientific). Samples were resuspended in 30 µL of 0.1% formic acid. For whole-protein ETD analysis, the sample was automatically desalted using a 1 × 10 mm protein Opti-Trap cartridge (Optimize Technologies, Oregon City, OR) and eluted using 50% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (v/v) directly into an electrospray ionization (HESI-II) probe (Thermo Scientific). The instrument was set up to cycle between different ETD reaction times (5 ms/10 ms/20 ms) and MS3 analysis using collision-induced dissociation (CID) as indicated in the Results section. Data were collected using the OrbiTrap mass analyzer in a mass range from m/z 500 to 1600 at 60 000 resolution, and ETD was performed on the most intense +14 charge state of the propeptide. For peptic digest analysis, the sample was desalted using a peptide 1 × 10 mm Opti-Trap cartridge and then separated on a 0.5 × 150 mm SB C-18 reversed-phase column (Agilent Technologies). Peptides were eluted at a 10 µL/min flow rate using a linear gradient from 2% to 50% actetonitrile in water containing 0.1% formic acid (v/v). The instrument was set up to collect survey scans at a mass range from m/z 400–2000 and cycle with ETD MS2 scans targeting histidine containing peptides at specific elution times. Specific elution times were determined by an initial test digest of unexchanged propeptide with the instrument set up for data-dependent MS2 fragmentation using higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) for peptides with charge states 1–2 and ETD for peptides with higher charge states.

Data Processing

For the whole protein ETD analysis, scans during the elution of the protein were averaged. The spectra generated using the three different reagent reaction times were searched for the expected isotopic distribution of all possible c and z fragments at charge states from +1 to +10. Fragments were considered identified if the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the expected and measured isotopic distribution was smaller than 10% at one of the different reaction times. If a fragment was found at multiple reaction times, the reaction time with the best RMSD was chosen. MS3 spectra were processed similarly by searching for features with the expected mass of all theoretical fragments. To identify peptic peptides, survey scans were searched for the expected isotopic distribution of all possible peptides, assuming no preferential cleavage of pepsin. Matches were ordered by intensity, and the identity of peptides with histidines was verified by manual inspection of triggered MS2 scans.

To determine the rate of hydrogen–deuterium exchange, one must calculate the deuterium uptake from mass measurements of the peptide or fragment ions. This information is encoded in the shifting pattern of the isotopic distribution. Previously, the uptake has been derived either from the ratio of the monoisotopic (I) and I + 1 peak4 or by calculating the average mass from the isotopic distribution, where the difference from the unexchanged average mass is used to quantify the uptake of deuterium.14 The first method has the disadvantage that it cannot be used in the cases of peptides containing two or more histidines. We also found that using the average mass was susceptible to artifacts due to the lowest-intensity peaks’ being unreliably detected. To overcome these problems, we chose to calculate the uptake by a fit of the observed isotopic distribution with a linear combination of the theoretical isotopic distributions of the nonexchanged and fully exchanged peptides, which, in the case of peptides containing single histidines, can be derived by simply shifting the peaks by one mass unit. Similar approaches have been used to determine ionic distributions15 for amide HDX16 and isotopic labeling.17 This concept can easily be extended to peptides containing multiple histidines by deriving theoretical models of complete exchange at two or more sites by shifting the peaks by two or more mass units. It also allows calculation of the uptake with only a subset of peaks, as long as the number of peaks is larger than the number of exchanging sites. For analysis of exchange at pH 10.0, where the number of exchanging site was unknown, we used the average mass for quantification of deuterium uptake. After calculation of uptake, the exchange rate was calculated using the following formula,4 where u is the calculated uptake and t is the exchange time:

| (1) |

The pKa and kmax values were derived by fitting the exchange rates at different pH values to the following equation:4

| (2) |

Data processing was performed using python scripts based on the mass spectrometry library of the mMass program.18

Homology Modeling and pKa Prediction

Homology models of PROFUR were built using the Modeler program19 using the automodel module. Five models were built for each of the 20 models deposited for PROPC1 NMR structure.20 pKa values were predicted using the PROPKA program version 3.1.21

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identifying Ions Containing a Single Histidine Residue Using Whole-Protein Electron-Transfer Dissociation and Proteolytic Digestion

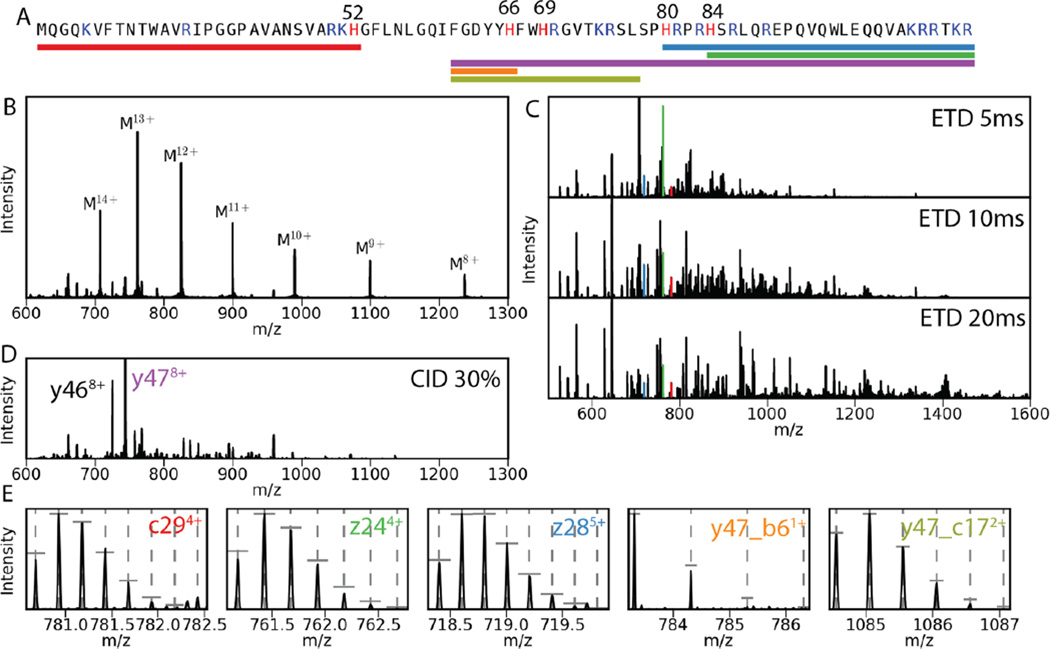

To measure deuterium uptake at individual histidines within a protein, it is essential to obtain peptides that contain a single histidine residue.4 This is often achieved using trypsin, a protease that cleaves proteins mainly at the C-terminus of lysine and arginine amino acids. However, a tryptic digestion of PROFUR fails to produce peptides that contain a single histidine residue, most likely because of the abundance of lysine (6%), arginine (13%), and histidine (6%) residues, as well as the presence of a 15-amino acid region that contains nine positively charged residues—four histidines and five arginine and lysines—as illustrated in Figure 1A. On the other hand, the high positive charge makes PROFUR a promising candidate for electron transfer dissociation (ETD), a process that induces fragmentation along the peptide backbone in a sequence-independent manner. Hence, we initially employed the easy-ETD module of the OrbiTrap Fusion instrument to fragment PROFUR inside the mass spectrometer in a “top-down” manner.

Figure 1.

Identification of ions for HD exchange measurements for individual histidines using the whole-protein ETD/CID approach. (A) Sequence of PROFUR with histidines colored red and other basic residues colored blue. Numbers indicate sequence position of histidines. Colored bars indicate the fragments that were used to measure individual histidine masses. (B) Mass spectrum of whole PROFUR. (C) Mass spectra after ETD reaction of the M14+ ion. Reaction time of ETD is indicated. Colored peaks indicate fragments used for later analysis. (D) Mass spectra after CID fragmentation at 30% collision energy. Most abundant fragments y47 and y46 are indicated. (E) Close-up of isotopic peaks of fragments used to measure deuterium uptake. Dashed vertical lines indicate expected m/z, and horizontal vertical lines indicate expected relative intensity given the natural isotopic abundances in the given peptides.

Injections of PROFUR into the OrbiTrap produce multiple charged states that range from +8 to +14 (Figure 1B). ETD fragmentation of PROFUR with a +14 charge produces a fragmentation pattern that is highly dependent on the reaction time (Figure 1C), where many fragments can be identified only at specific reaction times, either because they are not present or because they overlap with other fragments. Using various reaction times, 15 and 21 of the 83 possible c and z fragments, respectively, can be identified from the resulting MS2 spectra. A peptide fragment is considered suitable to quantify deuterium uptake only when the root-mean-square deviation between the observed and the expected isotopic distribution is smaller than 10%. The above criteria identify fragment ions c29 and z24 containing His52 and His84, respectively, along with ion z28 that includes His84 and His80, which can be used to calculate deuterium uptake of His80 by subtracting the deuterium uptake of His84. Although the fragment c46, which includes His52, His66, and His69, is observable, differentiating mass increases between His66 and His69 is not feasible because of the lack of appropriate smaller fragment ions.

To overcome this problem, we subjected PROFUR with a +14 charge to CID, which is a process that displays greater sequence-specific cleavage than ETD. Top-down methods for hydrogen/deuterium exchange of backbone amide hydrogen have been shown to be successful only when using ETD as a fragmentation mode22,23 because CID causes scrambling of exchanged deuterium along the protein backbone.24 However, scrambling during CID appears not to affect deuterium bound to the C2 of the imidazole side chain.25,26 The CID-MS2 spectrum identifies fragment y47 (+8 charged state) as the most intense ion (Figure 1D). The OrbiTrap Fusion allows the selection of the y47 ion for subsequent MS3 fragmentation using CID, which yields the fragment y47_b6, that only which contains only His66. The ETD fragmentation of y47 generates the y47_c17 ion, which contains both His66 and His69. The difference between the masses of y47_c17 and y47_b6 ions yields the mass increase of His69. Figure 1E shows the observed isotopic distribution of the fragment ions used for deuterium uptake determination.

To test whether this whole protein CID/ETD approach allows for accurate measurements of deuterium uptake into the imidazole side chain, we repeated the experiment by cleaving PROFUR using pepsin. Cleavage by pepsin produces peptides that allow the measurement of His52 and His66 (Figure 2A–B). Although pepsin digest produces a peptide containing His69 alone, it is of very low abundance because of low probability for cleavage at Phe67 and Thr73 and poor retention of the resulting peptide on the reverse phase chromatography column. Moreover, cleavage between His80 and His84 residues is not observed when using pepsin, and hence, ETD was employed to obtain accurate masses of fragments that contain His69, His80, and His84 (Figure 2C). Although this results in lower intensity of the fragment ions when compared with the whole peptide masses, it does not require determination of deuterium uptake by subtracting two mass measurements. Thus, using a combination of both ETD and CID in a “top-down” approach or pepsin cleavage and ETD, we successfully measured the mass of fragments that contain individual histidine residues.

Figure 2.

Identification of ions for HD exchange measurements for individual histidines using the pepsin/ETD approach. (A) Sequence of PROFUR with histidines colored red and other basic residues colored in blue. Numbers indicate sequence position of histidines. Colored bars indicate the peptides that were used to measure individual histidine masses. (B) Close up of isotopic peaks of peptides used to measure deuterium uptake. Dashed vertical lines indicate expected m/z, and horizontal vertical lines indicate expected relative intensity given the natural isotopic abundances in the given peptides. On the right, MS2 spectra generated by indicated fragmentation methods are shown to verify identification. Peaks associated with expected fragments are colored in green and labeled. (C) Close-up of isotopic peaks of ETD generated peptide fragments used to measure deuterium uptake. Dashed vertical lines indicate expected m/z, and horizontal vertical lines indicate expected relative intensity given the natural isotopic abundances in the given peptides.

Individual Histidine Residues in PROFUR Display Comparable pKa Values, But Vary in Their Solvent Accessibility

To calculate the pKa and kmax values for protonation of individual histidine residues, we performed HD exchange for 72h at 37 °C at different pH values as described in the methods and fitted the exchange rates of individual histidine residues to eq 2 (Figure 3). Since the fit indicates more than one exchanging site at high pH, we excluded the data points at pH 8.5 and 9.0 for His52 generated using the whole protein ETD/CID approach. Moreover, since PROFUR displays changes in conformation as a function of pH,11 the precise fitting of the exchange rates to eq 2, which assumes no changes in protein conformation, can report only the apparent pKa values (pKaapp) for the protonation of histidine residues.

Figure 3.

(A) Rate of HD exchange as a function of pH for individual histidine residues as determined by the whole-protein ETD/CID approach for PROFUR. Three data points for each pH are shown and are derived from independent experiments. The result of a nonlinear fit against eq 2 is shown as a solid line. Results of the fit are listed in Table 1. (B) Same as in panel A, but with data derived from the pepsin/ETD approach.

Both whole protein ETD/CID and pepsin digestion approaches demonstrate that the pKaapp values for all histidine residues are close to 6.0, whereas measurement of the maximal exchange rate kmax at the imidazole ring shows that individual histidine residues in PROFUR differ substantially in their solvent accessibility (Table 1). For example, His52 displays the highest rate of HD exchange when compared with all other histidine residues in PROFUR. It is worth noting that the kmax values obtained by the two methods are different for His52, His66, and His69, but are equal within measurement error for His80 and His84 (Table 1). The anomaly in kmax values for His52, His66, and His69 obtained using the different approaches is due to at least two factors: First, although the pepsin digest approach measures the mass increase in 10 residues around His52, the whole-protein ETD approach measures the mass increase in 28 residues N-terminal of His52. The analyses of these peptides demonstrate additional deuterium incorporation occurs in the R-group of amino acids located within the extra 19 residues present in the ETD, but not the pepsin digestion approach. The additional exchange is greatest at alkaline pH, explaining the multisite exchange observed at pH 8.5 and 9.0. This finding is described in more detail below (Figure 4). Second, the lower maximal exchange rate for His66 identified in the ETD/CID approach is likely a result of the low intensity of the y47_b7 fragment, which may lead to an underestimation of HD exchange. The exchange at His69 in the ETD/CID approach is computed by subtracting the exchange of His66 from the exchange into the y47_c16 ion, which likely leads to overestimation of deuterium uptake in His69. In retrospect, the pepsin digest approach appears to be less prone to artifacts, although the ETD approach provides insights into additional amino acids that could undergo HD exchange under alkaline conditions. Since in-instrument fragmentation techniques, such as CID and ETD, generate a single break in the peptide backbone, only exchange in the first N-terminal and C-terminal histidines can be directly measured using MS2 spectra. To quantify deuterium uptake at internal histidine residues, one must either use the difference between two fragments, or employ MSn spectra to further fragment peptide ions. Although the first approach correctly assigns deuterium uptake at His80 and His84 in PROFUR, it poses a disadvantage because errors in the measurement of the mass of individual fragments tend to be magnified. However, the second approach, which employs the MS3 spectra to measure the mass increase of His66, poses a disadvantage by severely reducing the intensity of the fragment ions, which may lead to the underestimation of histidine uptake. Certainly further advances in top-down mass spectrometry, such as charge-state pooling using Multi-Notch precursor selection,27 will help to overcome these difficulties.

Table 1.

Parameters of Histidine HD Exchange Rate Fits for PROFUR at Different pH Values Using eq 2

| whole protein ETD/CID | pepsin/ETD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| histidine | pKaapp | kmax | pKaapp | kmax |

| H52 | 6.04 ± 0.04 | 0.0175 ± 0.0003 | 6.07 ± 0.02 | 0.0124 ± 0.0001 |

| H66 | 5.84 ± 0.08 | 0.0045 ± 0.0002 | 5.98 ± 0.03 | 0.0069 ± 0.0001 |

| H69 | 6.13 ± 0.05 | 0.0155 ± 0.0003 | 6.04 ± 0.05 | 0.0063 ± 0.0002 |

| H80 | 6.04 ± 0.08 | 0.0112 ± 0.0003 | 6.02 ± 0.03 | 0.0094 ± 0.0002 |

| H84 | 5.96 ± 0.08 | 0.0077 ± 0.0003 | 6.04 ± 0.07 | 0.0073 ± 0.0002 |

Indicated errors are asymptotic standard parameter errors derived from a nonlinear fit using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm with three replicate measurements concatenated into one data set.

Figure 4.

(A) Deuterium uptake as a function of pH into fragment c29 of PROFUR determined by a fit of the isotopic distributions against a model of two exchanging sites. (B) Deuterium uptake into histidine-free peptides as a function of pH. (C) Deuterium uptake at pH 10.0 into histidine-free peptides in either H2O or D2O buffer. (D, E) Deuterium uptake into CID-generated (D) or ETD-generated (E) fragments of the 25MQGQKVFTNTW36 and 25MQGQKVFTNT35 peptides after exchange for 72 h at pH 10. The different ion series are color-coded and connected by lines. Uptake as determined by whole peptide masses is indicated in green, including the uptake into the 25MQGQKVFT33 peptide. (F) Deuterium uptake into CID-generated fragments of the 37AVRIPGGPAVANS49 peptide after exchange for 72 h at pH 10. The b and y series are color-coded and connected by lines. Uptake as determined by whole peptide masses is indicated in green, including the uptake into the 37AVRIPGGPAVA47 peptide.

Overall, these finding suggest that the local protein environment only marginally influences the protonation equilibrium of the imidazole side chain in PROFUR, but influences the maximal HD exchange rates. The maximal exchange rates normally cannot be directly compared between histidines because they depend on the pKa. In this case, when the pKa values are equal, the higher kmax values for His52 and His80 compared to His66, His69, and His84 must be due to differences in the local protein environment, for example, in solvent accessibility or hydrogen bonding patterns.5,14

Alkaline pH Induces HD Exchange in Carbon-Bound Protons in Addition to the C2 Proton of the Imidazole Ring

Because the c29 fragment in PROFUR appears to exchange at more than one site under conditions of alkaline pH (pH ≥ 8.5), as described earlier, we next investigated whether (i) carbon-bound protons residues other than the C2 proton of the imidazole ring in histidine can undergo HD exchange and (ii) deuterium uptake can be analyzed in pepsin-derived peptides that lack histidine residues. Quantification of deuterium uptake by fitting the experimental data to a model with two exchanging sites shows that an increase in pH above 8.0 enhances deuterium uptake into the c29 fragment (Figure 4A). This indicates that the additional exchange at high pH is not due to conformational changes that might influence the exchange rates, but instead is due to exchange at a site different from the C2 of His52. Analysis of pepsin-generated peptides establishes that peptides 25MQGQKVFTNTW36 and 37AVRIPGGPANSVA49, which are N-terminal of His52 and are part of the c29 fragment ion, demonstrate deuterium uptake at pH 8.5 and 9.0 (Figure 4B). The magnitude of these mass increases is consistent with the additional HD exchange observed in the c29 fragment obtained using ETD. However, peptides 57GQIFGGDY64 and 88QREPQVWL95, which also lack histidine residues, demonstrate no deuterium uptake at pH 8.5 and 9.0. Because the additional HD exchange at alkaline pH may result from the fact that an increasing OH− concentration likely removes carbon-bound protons at other residues, experiments were also conducted at a pH of 10.0. The results demonstrate the magnitude of deuterium uptake increases in the peptides 25MQGQKVFTNTW36 and 37AVRIPGGPANSVA49, but also causes deuterium uptake within peptides 57GQIFGGDY64 and 88QREPQVWL95, which display no HD exchange at pH of 9.0 (Figure 4C). Identical experiments conducted in nondeuterated buffer at pH 10.0 show no mass increase, thus confirming the mass increase observed in deuterated buffers results from HD exchange and as a result of chemical modifications, such as a deamidation event that would also cause a 1 Da mass increase.28

To investigate which residues undergo HD exchange at alkaline pH, we monitored deuterium uptake within CID fragments of 25MQGQKVFTNTW36 and 37AVRIPGGPANSVA49 at pH 10.0 (Figure 4D, F). Our analyses show that in both cases, asparagine residues are most prone to uptake of deuterium, with additional (albeit smaller) uptake in glycine, glutamine, and threonine residues. Although in the 25MQGQKVFTNTW36 peptide deuterium uptake seems to be mediated by multiple residues, in the 37AVRIPGGPANSVA49 peptide, deuterium uptake is clearly limited to Asn46 and Gly43, and Gly42 shows no uptake. This indicates that slow HD exchange in residues other than histidine is dependent not only on the chemical nature of the side chain, but also on the context of the local environment within the protein. To test whether scrambling of bound deuterons might obfuscate our measurements,29 we also performed ETD fragmentation. Because of the low charge state (+2) of the peptides, we could obtain usable data only for MQGQKVFTNTW (Figure 4E). Consistent with the CID data, the measured deuterium uptake suggests uptake into glycine, glutamate, threonine, and asparagine residues.

The mass increases may be due to HD exchange of backbone amides with very slow kinetics, as they are occasionally noted in proteins;30 however, they are still observed after back-exchange of already digested protein. It is hard to imagine that small peptides could provide such strong protection of backbone amides. This leads to the possibility that protons bound to carbon atoms other than the C2 carbon of the imidazole ring can exchange at alkaline pH. On the basis of previous literature, the most likely candidate is protons bound to Cα atoms, which can exchange with solvent during a racemization reaction. Indeed, we did observe deuterium uptake in residues that are prone to racemization. Whereas the racemization of glycine normally has no effect, it leads to exchange of Cα protons with the solvent, as has been observed in N-substituted glycine-containing peptides at a pD of 12.3.29 However, the majority of the exchange at pH 8.5 and 9.0 can be attributed to asparagine (Figure 4 D–F). Asparagine is prone to racemization because of formation of a succinimide intermediate31 whose product due to the low concentration of ammonia compared to water is almost always an aspartate. The tetrahedral intermediate during succinimide formation, however, can racemize back to an asparagine-containing peptide.32 We therefore propose that the observed HD exchange in asparagine is due to transient formation of the tetrahedral intermediate. Our data furthermore suggest that threonine residues could make minor contributions. HD exchange in small polar residues has been observed in immunoglobulins, where serine residues show deuterium uptake after incubation at pH 8 and 40 °C for 4 weeks, also due to racemization reactions.33

This observation shows that caution must be used when measuring histidine pKa by HD exchange to remove this influence from curve fittings. This is easily achieved in practice because this exchange shows a characteristic pH profile, whereas no saturation of the exchange rate is observed at basic pH. Although in this study the unexpected exchange observed at residues other than histidine was an artifact, it may be useful in the study of protein aging and misfolding. Because racemization depends on local flexibility of the protein backbone, it may also be helpful in studying disordered protein regions and warrants further study.

His72 in PROPC1 Displays a pKaapp Shifted to a More Acidic Value

PROFUR and PROPC1 adopt similar three-dimensional structures but differ in the density and distribution of histidine residues within their otherwise conserved sequences. Circular dichroism studies demonstrate that PROPC1 requires an ~10-fold higher proton concentration to undergo a 50% loss in its secondary structure when compared with PROFUR.11 Consistent with these studies, biochemical approaches show that PROFUR mediates activation of MATFUR at a pH of 6.5, whereas its paralog, PROPC1, modulates activation of MATPC1 at a pH of 5.5. The lower pH of activation of PROPC1 may result from lower pKa values of a subset or all histidine residues in the propeptide. To examine this possibility, we measured the pKa values of individual histidine residues in PROPC1 using the pepsin/ETD hybrid approach that gives the best results for PROFUR (Figure 5). The results demonstrate that three of the four histidine residues have pKaapp values of ~6.0, similar to those in PROFUR. However, His72, displays a substantially lower pKaapp value of 5.6 (Table 2). Although the maximal exchange rates are slightly less than those observed for PROFUR, this finding is consistent with the higher structural stability PROPC1.

Figure 5.

Rate of HD exchange as a function of pH for individual histidine residues in PROPC1. Three data points for every pH are shown and are derived from independent experiments. The result of a nonlinear fit against eq 2 is shown as a solid line. Results of the fit are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of Histidine HD Exchange Rate Fits for PROPC1 at Different pH Values Using eq 2

| histidine | pKaapp | kmax |

|---|---|---|

| H67 | 6.31 ± 0.03 | 0.0068 ± 0.0001 |

| H72 | 5.61 ± 0.06 | 0.0034 ± 0.0001 |

| H75 | 5.97 ± 0.03 | 0.0057 ± 0.0001 |

| H85 | 5.85 ± 0.04 | 0.0052 ± 0.0001 |

Indicated errors are asymptotic standard parameter errors derived from a nonlinear fit using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm with three replicate measurements concatenated into one data set.

A Structural Interpretation of Histidine pKa Values

Our data suggest that histidines within PROFUR display similar pKaapp values but differ in their observed exchange rates, whereas individual histidines in PROPC1 display substantial differences in their pKaapp values. How can one rationalize these differences using available sequence and structural information? A sequence alignment between PROFUR and PROPC1 establishes that only one histidine, His69 in PROFUR, has a direct equivalent in His72 within PROPC1 (Figure 6A). His52 in PROFUR is unique with no direct counterpart in PROPC1. The other histidine residues are not directly identical in their positions but are all situated around the second cleavage site, Arg72 and Arg78, in PROFUR and PROPC1, respectively. To analyze this in a structural context, we created homology models of PROFUR based on the solution NMR structure of PROPC1 (Figure 6B,C).

Figure 6.

(A) Sequence alignment of human PROFUR and PROPC1. Conserved residues are shaded in gray, and histidines are shown in red. (B) Solution NMR structure of PROPC1.20 All 20 deposited structures are superimposed. Histidine residues are shown in stick representation and color coded according to Figure 5. (C) Homology model of PROFUR based on PROPC1. Best scoring model based on each of the 20 deposited structures of PROPC1 are superimposed. Histidine residues are shown in stick representation and color-coded according to Figure 3. (D) Histidine pKa predictions of PROFUR using the PROPKA program. Predictions based on five models per template structure are shown as a boxplot with the median shown as a bold line, the interquartile range shown as a box, and the range defined as 1.5 times the interquartile range shown as whiskers. Outliers are shown as black spheres. The experimentally determined pKaapp values are shown as a dashed red line. (E) Histidine pKa predictions of PROPC1 using the PROPKA program. Predictions are based on each of the 20 deposited structures. Data are depicted as described for panel D.

To rationalize the measured pKaapp values, we used the PROPKA program to predict histidine pKa values based on the NMR solution structures of PROPC1 and the PROFUR homology models (Figure 6D,E). In the case of PROPC1, the predicted pKa values are consistent with the measured pKaapp values for His67, His75, and His85. His72 is predicted to have the most basic pKa values of all histidines, and it has the most acidic pKaapp. Interestingly, for two of the 20 NMR structures, the pKa of His72 is predicted to be strongly acidic. In these structures, the imidazole side chain is not exposed to the solvent but is packed under residues of the cleavage loop. Theoretical consideration of pH sensing suggests that titratable residues involved in pH-driven structural changes should have divergent theoretical pKa values in the two different structural states with an observed pKa value that is between these two values.34 Because the observed pKaapp is between the pKa predicted for His72 buried within the loop and His72 pointing toward the solvent, this suggests that movement of His72 from the buried conformation toward the solvent is part of the pH-sensing mechanism. The fact that His72 is the residue corresponding to the previously identified primary pH sensor His69 in PROFUR confirms a central role in pH-sensing, although specific histidine residues are likely to augment the sensitivity of His72 in PROPC1 (Williamson, D. M.; Elferich, J.; Shinde, U. Mechanism of Fine-tuning pH Sensors in Proprotein Convertases: Identification of a pH-sensing Histidine Pair in the Propeptide of Proprotein Convertase 1/3. Manuscript submitted for publication).

Predicted pKa values for PROFUR vary substantially between histidines compared with the consistent pKaapp values that were measured. The predicted pKa for His52 is especially acidic, probably because of burial of His52 between the two alpha helices. The observed maximal exchange rates are also not consistent with the homology model. His52, which is buried in the homology model, has the highest exchange rate, and His66, which is completely solvent-exposed in the model, has one of the slowest exchange rates. This might be due to low quality of the homology model due to the low sequence identity (~40%) and the fact that PROFUR in solution shows strong structural dynamics and probably is in a molten-globule-like state.35

Because association with the protease likely stabilizes the propeptide structure, this might change the effect of histidine protonation. However, because the propeptide/protease complex is not stable enough in vitro (data not shown) we are currently limited to studying isolated propeptides. Because the PROPC1 solution structure is similar to structures of propeptides in complex with proteases,20 it is likely that principles observed in isolated propeptides also apply to the complex.

CONCLUSION

Previous knowledge about the pH sensing mechanism of proprotein convertases was based on mutagenesis of histidine residues, which might introduce artifacts in addition to the removal of a titratable group. Therefore, the use of the histidine HD exchange method on wild-type propeptides provides orthogonal knowledge. We show that although all histidines in PROFUR show a similar pKaapp, they do experience different local environments. We furthermore show that the activation of PC1/3 at lower pH can be explained by a shift of the pKa of the primary pH sensor His72 to a more acidic value. Comparison of this value with predictions based on a NMR structure suggests the movement of the conserved primary pH sensor His72 from a protected pocket toward the solvent may be one of the key events in pH-mediated activation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (Career Award MCB0746589), the U.S. National Institutes of Health (5F30DK096752 NRSA fellowship to D.M.W.), and the American Heart Association (predoctoral training Grant 12PRE11470005 to J.E., who is currently a Vertex scholar). We thank Gary Thomas for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schoönichen A, Webb BA, Jacobson MP, Barber DL. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013;42:289–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimsley GR, Scholtz JM, Pace CN. Protein Sci. 2009;18(1):247–251. doi: 10.1002/pro.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11(1):50–61. doi: 10.1038/nrm2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyagi M, Nakazawa T. Anal. Chem. 2008;80(17):6481–6487. doi: 10.1021/ac8009643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullangi V, Zhou X, Ball DW, Anderson DJ, Miyagi M. Biochemistry. 2012;51(36):7202–7208. doi: 10.1021/bi300911d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullangi V, Mamillapalli S, Anderson DJ, Bann JG, Miyagi M. Biochemistry. 2014;53(38):6084–6091. doi: 10.1021/bi500718g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seidah NG, Prat A. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2012;11(5):367–383. doi: 10.1038/nrd3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinde U, Thomas G. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;768:59–106. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-204-5_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson ED, VanSlyke JK, Thulin CD, Jean F, Thomas G. EMBO J. 1997;16(7):1508–1518. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S-N, Prodhomme E, Lindberg I. J. Endocrinol. 2004;182(2):353–364. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1820353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillon SL, Williamson DM, Elferich J, Radler D, Joshi R, Thomas G, Shinde U. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;423(1):47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feliciangeli SF, Thomas L, Scott GK, Subbian E, Hung C-H, Molloy SS, Jean F, Shinde U, Thomas G. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(23):16108–16116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600760200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson DM, Elferich J, Ramakrishnan P, Thomas G, Shinde U. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288(26):19154–19165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.442681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi N, Kuyama H, Nakajima C, Kawahara K, Miyagi M, Nishimura O, Matsuo H, Nakazawa T. Biochemistry. 2014;53(11):1818–1826. doi: 10.1021/bi401260f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senko MW, Beu SC, McLaffertycor FW. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1995;6(4):229–233. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chik JK, Vande Graaf JL, Schriemer DC. Anal. Chem. 2006;78(1):207–214. doi: 10.1021/ac050988l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dasari S, Wilmarth PA, Reddy AP, Robertson LJG, Nagalla SR, David LL. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8(3):1263–1270. doi: 10.1021/pr801054w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strohalm M, Kavan D, Novák P, Volný M, Havlíček V. Anal. Chem. 2010;82(11):4648–4651. doi: 10.1021/ac100818g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eswar N, Eramian D, Webb B, Shen M-Y, Sali A. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;426:145–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tangrea MA, Bryan PN, Sari N, Orban J. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320(4):801–812. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olsson MHM, SØndergaard CR, Rostkowski M, Jensen JH. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:525–537. doi: 10.1021/ct100578z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rand KD, Zehl M, Jørgensen TJD. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:3018–3027. doi: 10.1021/ar500194w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan J, Han J, Borchers CH, Konermann L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12801–12808. doi: 10.1021/ja904379w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jørgensen TJD, Gårdsvoll H, Ploug M, Roepstorff P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2785–2793. doi: 10.1021/ja043789c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyagi M, Wan Q, Ahmad MF, Gokulrangan G, Tomechko SE, Bennett B, Dealwis C. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cebo M, Kielmas M, Adamczyk J, Cebrat M, Szewczuk Z, Stefanowicz P. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014;406(30):8013–8020. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8218-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McAlister GC, Nusinow DP, Jedrychowski MP, Wühr M, Huttlin EL, Erickson BK, Rad R, Haas W, Gygi SP. Anal. Chem. 2014;86(14):7150–7158. doi: 10.1021/ac502040v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H, Zubarev RA. Electrophoresis. 2010;31(11):1764–1772. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachor R, Setner B, Kluczyk A, Stefanowicz P, Szewczuk Z. J. Mass Spectrom. 2014;49:43–49. doi: 10.1002/jms.3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kheterpal I, Zhou S, Cook KD, Wetzel R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97(25):13597–13601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250288897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radkiewicz JL, Zipse H, Clarke S, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:9148–9155. doi: 10.1021/ja0026814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li B, Borchardt RT, Topp EM, VanderVelde D, Schowen RL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125(38):11486–11487. doi: 10.1021/ja0360992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang L, Lu X, Gough PC, De Felippis MR. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:6363–6369. doi: 10.1021/ac101348w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Russo NV, Martí MA, Roitberg AE. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014;118(45):12818–12826. doi: 10.1021/jp507971v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhattacharjya S, Xu P, Xiang H, Chrétien M, Seidah NG, Ni F. Protein Sci. 2001;10(5):934–942. doi: 10.1110/ps.41301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]