Abstract

Trichilemmal carcinoma is a cutaneous adnexal tumor originating from the outer root sheath of hair follicle, and it was first described by Headington in 1976. Clinically, it usually occurs as an asymptomatic solitary papule, nodule or mass on the face or scalp. This neoplasm is a malignant counterpart of trichilemmoma, and it has been reported in the literature as trichilemmal carcinoma, tricholemmal carcinoma, malignant trichilemmoma, and tricholemmocarcinoma. Although histologically, trichilemmal carcinoma frequently has maliganant features, it has a relatively benign clinical behavior. We think Mohs micrographic surgery is a useful treatment modality in trichilemmal carcinoma because the final skin defect is smaller than a wide excision. We report a case of primary trichilemmal carcinoma which had developed on the face, treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Keywords: Mohs micrographic surgery, Trichilemmal carcinoma

CASE REPORT

A 70-year-old Korean man visited the Department of Dermatology at Dong-A University Hospital on February 4, 2004 with a 2-year history of a 1.0×1.0 cm ulcerated plaque on the left cheek. The lesion enlarged slowly with bleeding tendency on the surface (Fig. 1). He had a past history of liver cirrhosis with elevated liver enzymes and serologic markers of hepatitis B virus infection. Abdomen computerized tomography and ultrasonograghy showed hepatosplenomegaly without any evidence of regional lymph node metastasis. We could not find any abnormal findings on the head and neck computerized tomography either.

Fig. 1. 1.0×1.0 cm sized ulcerative plaque on the left cheek for 2 years.

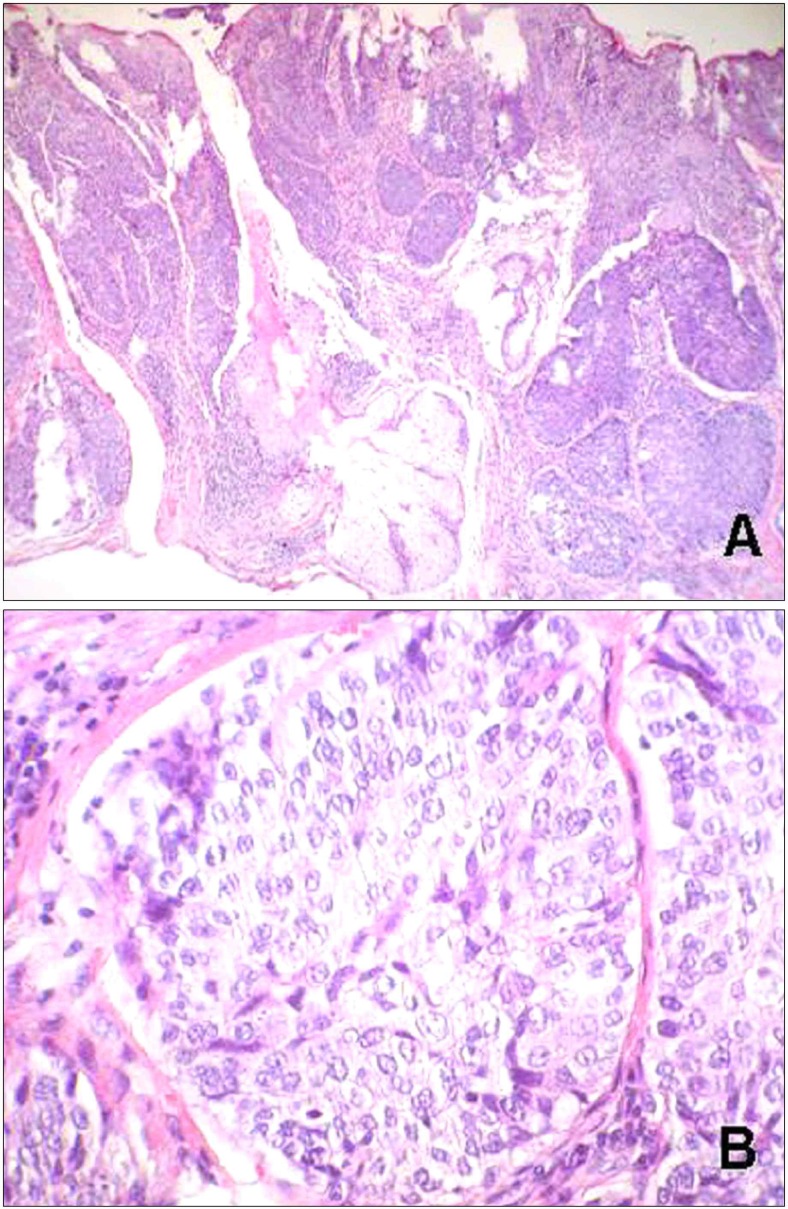

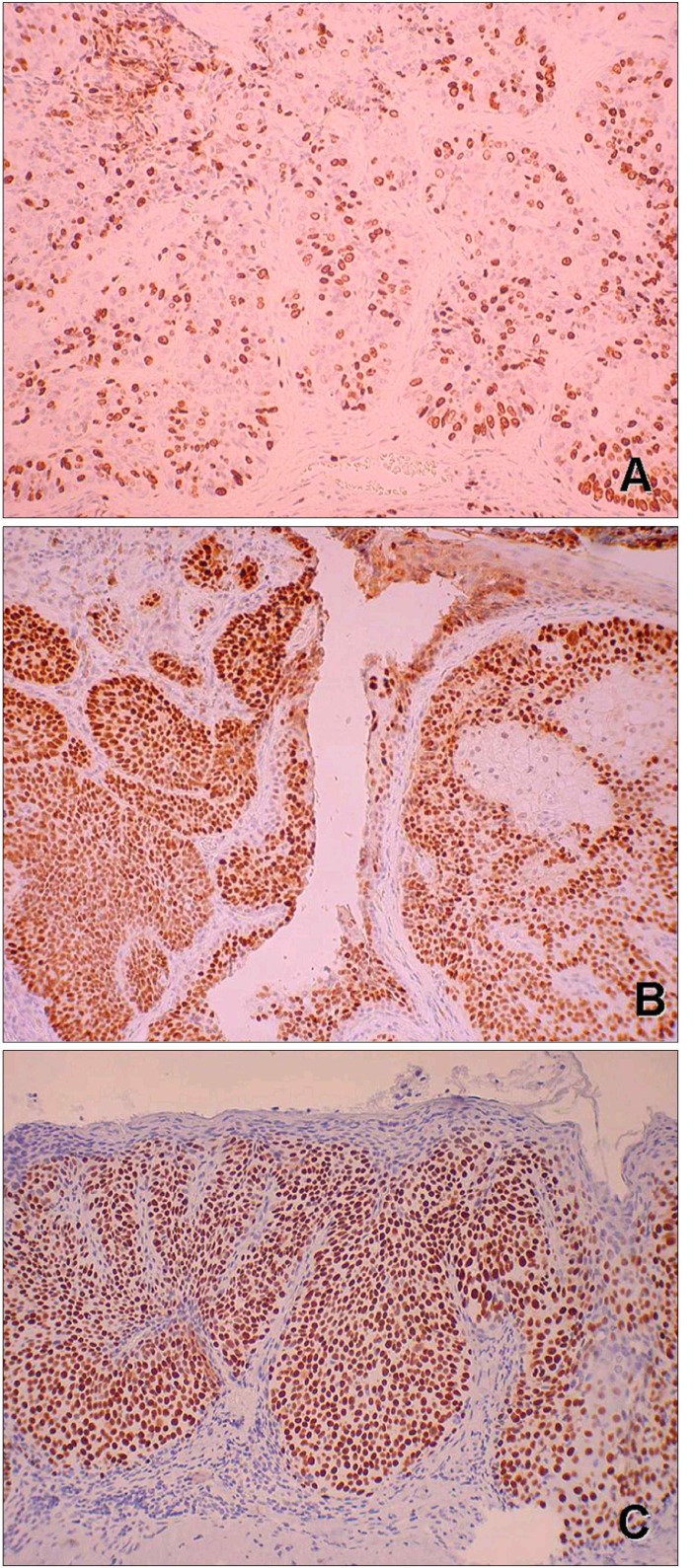

An incisional biopsy was done under the impression of squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathologically, we could observe a relatively well-circumscribed tumor, which was connected with the epidermis and extended throughout the dermis. The tumor mass showed the multiple lobular or trabecular pattern of proliferation. The central cells in each lobule had a pale or clear cytoplasm, and the peripheral cells of each lobule were in palisading arrangement and trichilemmal keratinization was observed within the lobules. Tumor cells showed pleomorphism and nuclear atypia with low grade of mitotic activity (Fig. 2). PAS staining revealed positive and diastase labile in the cytoplasms of clear cells. Immunohistochemistry studies resulted in positivity for high molecular weight cytokeratin and EMA, but negativity for CEA, S-100 protein, or cytokeratin 17. Many tumor cells expressed Ki-67, mutant p53 protein, and p63 abundantly in a diffuse pattern (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. (A) Infiltrative epithelial lobules and clear cells extended downward from the epidermis (H& E stain, ×40). (B) Nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic figures are remarkable and clear cells were in palisading arragement (H& E stain, ×200).

Fig. 3. (A) Ki-67 positive cells are diffusely present in tumor lobules (Ki-67 stain, ×100). (B, C) Tumor lobules were strongly positive for p53 and p63 (p53 protein, p63 stain, ×100).

Trichilemmal carcinoma was completely removed with Mohs micrographic surgery. When the incision is sufficient to reach the subcutaneous fat layer, then the basal area is cut with a single-11th bladed scalpel. The base was excised within the subcutaneous layer. Tumor was subdivided into 4 margins, 4 base dissections. Hematoxylin and eosin stains were used for all microscopic sections. The histologic findings were similar to the initial biopsy specimen. Clear margins were achieved after three stages of Mohs' surgery. The final surgical defects measured 1.8×1.8 cm. The tumor defect was covered by direct closure. The final shape and texture were satisfactory. A total of 19 months follow-up showed no evidence of metastasis or recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Trichilemmal carcinoma is a malignant tumor originating from the outer root sheath of the hair follicle described by Headington in 19761. Trichilemmal carcinoma, one of the malignant counterparts of trichilemmoma, usually occurs in the elderly in a 3:1.6 female-male ratio3. The lesion occurs as an asymptomatic solitary papule, keratotic nodule, and indurated plaque with crusted, smooth surfaced cover or ulceration on sun-exposed areas such as the face and scalp.

Histopathologically, trichilemmal carcinoma shows many features resembling the outer root sheath of the hair follicle. Tumors grow in lobular and infiltrative patterns, and the lobules are often centered on or expanding out of a pilosebaceous unit. The tumors are frequently connected to the follicular epithelium and the interfollicular epidermis and usually invade to the reticular dermis. The center of the lesion is composed of clear cells and palisading of tumor cells at the periphery of the tumor lobules can also be appreciated1,5,6,7. Clear tumor cells show a various growth pattern: (1) a solid growth pattern characterized by sheets of monotonous tumor cells with expansile, pushing borders, (2) a lobular pattern characterized by clear cells grouped into discrete nests and lobules, and (3) a trabecular pattern characterized by thick cords of tumor cell arranged in a serpiginous fashion8. Headington pointed out a characteristic finding, which tumor cells showed clear glycogen rich cytoplasms and atypical nuclei with high mitotic index and pleomorphism in contrast to those of trichilemmoma5,9,10. There have been few cases reported however that have been accompanied by either vascular or perineural invasion3,11,12.

Immunohistochemical studies have shown PAS-positive, diastase sensitive clear cytoplasm with negativity for CEA and EMA. But there were some reports that trichilemmal carcinoma showed positivity for EMA3. Trichilemmal carcinoma is known to originate from the bulge area of the outer root sheath, as recently it has been reported to show positivities for cytokeratin 17 and CD3412,13. However,in this case, tumor cells were negative for cytokeratin 17 and CD34. Most cases showed positivityfor low molecular weight cytokeratin (cytokeratin 1,5, 10, 14) like in this case.

Trichilemmal carcinoma could occur in a burn ulcer, a scar of discoid lupus erythematosus, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, and a lesion of solar keratosis14. Takata M et al4 reported a case of trichilemmal carcinoma arising in the wall of a proliferating trichilemmal cyst. And they reported the p53 mutation was a C to T transition within CpG dinucleotide, and Ki-67 antigen was as high as 42% in trichilemmal carcinoma.

In this case, overexpression of Ki-67 antigen, mutant p53 protein, and p63 were diffusely found (Fig. 3). A clonally patterned p53 immunoreactivity in tumor nests were prominent features in this case (Fig. 3A). Epidermal p53 clones have been reported to be closely associated with ultraviolet radiation exposure and skin cancer. p63 is a diagnostic marker of basal/progenitor cells of the adnexal tumors. p63 might block the apoptosis inducing activity of p53 and thus could maintain the proliferative capacity of basal/progenitor cells15,16. P63 expression was also reported in trichilemmal carcinoma15. In our case, the distribution of p63 positive cells in tumor nests is similar to p53 (Fig. 3B, C).

Trichilemmal carcinoma needs to be differentiated from many other clear cell tumors of the skin. The phenomenon of cytoplasmic clearing may be observed focally or represent the dominant feature in various kinds of tumors originating from the epidermis or within the dermis showing well-defined features of eccrine, sebaceous, and follicular lines of differentiation8. Hair follicle origin tumors include desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, tricofolliculoma, proliferating trichilemmal tumor, and malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor. In proliferating trichilemmal tumor, areas showing clear cell changes and palisading of columnar epithelium comprise only a minor proportion of proliferating trichilemmal tumors. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor is more keratinized and has a stronger tendency towards metastasis than trichilemmal carcinoma6. Non hair follicle origin tumors include clear cell squmous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, balloon cell melanoma, clear cell acanthoma, clear cell syringoma, sebaceous gland carcinoma, metastatic renal cell carcinoma17. Clear cell squamous cell carcinoma differs from trichilemmal carcinoma in that it lacks foci of the peripheral margination of nuclei with subnuclear vacuolization reminiscent of outer root sheath differentiation and increased intracellular glycogen deposition8.

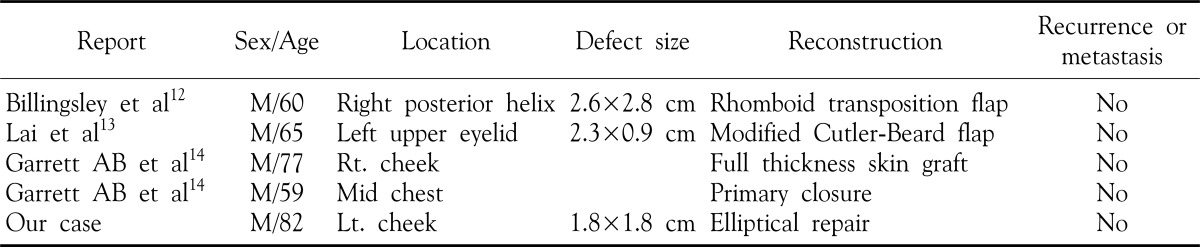

Wide excision is the preferred treatment for trichilemmal carcinoma. According to Wong and Suster, in the outcomes of 13 patients with wide excision, neither recurrence nor metastasis was found5. Mohs micrographic surgery has some advantages including high cure rate, smaller defect size, low recurrence rate and immediate reconstruction9. Billingsley, Lai, and Garrett performed Mohs micrographic surgery because of the histologically malignant feature of this tumor, although clinically, metastasis and recurrence are rare (Table 1)7,18,19. In this case, trichilemmal carcinoma was treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and no metastasis was found during the 19 months of follow-up. We recommend that Mohs micrographic surgery is an ideal option because it provides a tissue-sparing method to immediately assess tissue margins, allowing for complete surgical removal of the tumor.

Table 1. Reported cases of trichilemmal carcinoma treated by Mohs micrographic surgery in worldwide.

Footnotes

This study was supported by research funds from Dong-A University.

References

- 1.Headington JT. Tumors of the hair follicle. A review. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:479–514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boscaino A, Terracciano LM, Donfrio V. Trichilemmal carcinoma: a study of seven cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:94–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1992.tb01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reis JP, Tellechea O, Cunha MF, Baptista AP. Trichilemmal carcinoma: review of 8 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:44–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1993.tb01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takata M, Rehman I, Rees JL. A trichilemmal carcinoma arising from a proliferating trichilemmal cyst: the loss of the wild-type p53 is a critical event in malignant transformation. Human Pathol. 1998;29:193–195. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong TY, Suster S. Tricholemmal carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 13 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:463–473. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park HJ, Park YM, Yi JY, Kim TY, Cho BK, Kim CW, et al. A case of trichilemmal carcinoma. Ann Dermatol. 1996;8:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrett AB, Azmi FH, Ogburia KS. Trichilemmal carcinoma: a rare cutaneous malignancy: a report of two cases. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:113–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suster S. Clear cell tumors of the skin. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1996;13:40–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanson PE, Marrogi AJ, Williams DJ, Cherwitz DL, Wick MR. Tricholemmal carcinoma: clinicopathologic study of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:100–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1992.tb01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SY, Song WK, Hahm JH. A review of Mohs micrographic surgery and reconstruction of cutaneous malignant tumors over the past 10 years. Korean J Dermatol. 2005;43:1013–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Headington JT. Trichilemmal carcinoma. J Cut Pathol. 1992;19:83–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1992.tb01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allee JE, Cotsarelis G, Solky B, Cook JL. Multiply recurrent trichilemmal carcinoma with perineural invasion and cytokeratin 17 positivity. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:886–889. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurokawa I, Nishijima S, Kusumoto K, Senzaki H, Shikata N, Tsubura A. Trichilemmoma: an immunohistochemical study of cytokeratins. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:99–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misago N, Tanaka T, Kohda H. Trichilemmal carcinoma occurring in a lesion of solar keratosis. J Dermatol. 1993;20:358–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1993.tb01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivan D, Hafeez Diwan A, Prieto VG. Expression of p63 in primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasms and adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:137–142. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsujita-Kyutoku M, Kiuchi K, Danbara N, Yuri T, Senzaki H, Tsubura A. p63 expression in normal human epidermis and epidermal appendages and their tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:11–17. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.300102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim SH, Yang JK, Kim YS, Baek SC, Byun DG, Houh D. A case of trichilemmal carcinoma on the lower lip. Korean J Dermatol. 1999;37:1673–1675. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billingsley EM, Davidowski TA, Maloney ME. Trichilemmal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:107–109. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai TF, Huilgol SC, James CL, Selva D. Trichile-mmal carcinoma of the upper eyelid. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003;81:536–538. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]