Abstract

Background

The etiology of porokeratosis (PK) remains unknown, but immunosuppression is known to be a factor in the pathogenesis of PK and it may also exacerbate PK.

Objective

The aim of this study was to examine the clinical characteristics of PK associated with immunosuppressive therapy in renal transplant recipients.

Methods

A total of 9 renal transplant patients diagnosed with biopsy-proven PK from January 2001 to December 2006 were enrolled. The authors analyzed the patient and medication histories, clinical characteristics, and associated diseases.

Results

The ages of the 9 patients ranged from 38 to 67 years (mean 52 years). All received multi-drug regimens comprised of two or three immunosuppressive agents (steroids, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine and/or tacrolimus). Times between transplantation and the onset of PK ranged from 2 to 9 years (mean 4.1 years). No family history of PK or a history of intense sun-exposure was elicited. The number of the lesions was less than ten in 8 of the 9. Lesions were mainly located in the extremities, though some affected the trunk or neck (3). Three patients had disseminated superficial actinic PK (DSAP), PK Mibelli, or both types. Associated diseases included verruca (4), recurrent herpes simplex (1), actinic keratosis (1), and cutaneous B cell lymphoma (1).

Conclusion

The three clinical patterns of PK occurred equally in our patients, namely, coexistent PK Mibelli and DSAP, or the DSAP and Mibelli types as independent forms. Our findings support the notion that the different variants of PK be viewed as parts of a heterogeneous clinical spectrum. Further studies are needed in order to establish the clinical patterns of PK in immunosuppressed patients.

Keywords: Immunosuppression, Porokeratosis, Renal transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Porokeratosis (PK) is a specific keratinization disorder, and is histologically characterized by the presence of a cornoid lamella, a thin column of closely stacked, parakeratotic cells that extend through the stratum corneum. Clinically, the basic lesion is sharply demarcated and hyperkeratotic, and may be annular with central linear or punctate atrophy. Five clinical variants are recognized, namely, PK Mibelli, PK palmaris et plantaris disseminata, linear PK, punctate PK, and disseminated superficial PK (DSP) and disseminated superficial actinic PK (DSAP)1.

The etiologies of the different PK variants have not been established, but they are certainly multifactorial. Additional factors are presumed to trigger clinical manifestations in genetically disposed skin.Irradiation with ultraviolet (UV) light and systemic immunosuppression have been considered to be factors that trigger lesion development in several cases, and it has been suggested that this occurs due to an impairment of the immune surveillance function of Langerhans cells2,3. A significant number of PK cases have been reported to be associated with chemotherapies administered due to malignancy, organ transplantation, or systemic corticosteroid therapy, and more recently due to human immunodeficiency virus infection4,5,6. In particular, two large series of renal transplant recipients, found PK prevalences of 0.34%7 and 10.68%8. The clinical pattern of PK associated with immunosuppression was DSAP in most patients, though a recent report found that the mixed pattern of PK Mibelli and DSAP was most prevalent8.

Overseas, multiple case reports and series have described the development of PK in the setting of immunosuppression, which is widely recognized following solid organ transplantation. To the best of our knowledge, only three cases of PK following renal or heart transplantation have been reported in the Korean dermatological literature9,10,11.

Here we report the clinical characteristics of 9 cases with PK associated with immunosuppressive therapy in renal transplant recipients who were treated at our hospital over the last 6 years. In addition, we include a review of the medical literature concerning the association between PK and immunosuppression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We reviewed the charts of 20 patients diagnosed with PK by skin biopsy at our Department of Dermatology from January 2001 to December 2006. Of these 20 patients, 9 patients with a history of renal transplantation were included, and their clinical characteristics and skin biopsy slides were reviewed. During this period, 298 renal transplantations were conducted at our hospital.

Clinical evaluations were performed on all 9 patients with respect to age, gender, medical and family history of PK and associated diseases. In addition, we examined the clinical features of the lesions, PK onsets after renal transplantation, regimen types, and durations of immunosuppressive therapy, and assessed therapeutic responses.

RESULTS

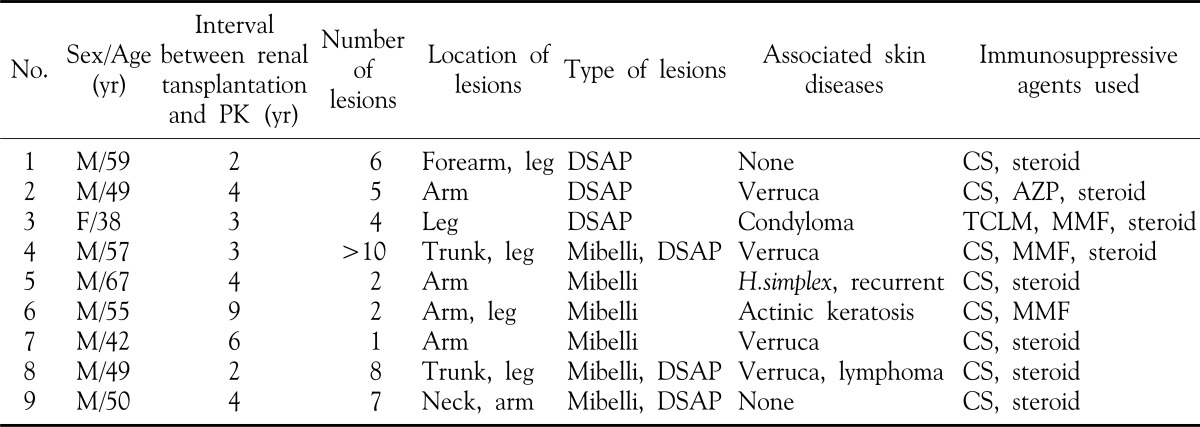

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the 9 renal transplant recipients with PK. At dermatological examinations, patient ages ranged from 38 to 67 years (mean age: 52 years). There were eight men and one woman, and no patient had previous or family history of PK. All patients had received renal allograft transplantation because of chronic renal failure. After renal transplantation, they received multi-drug regimens comprised of two or three immunosuppressive agents, namely, steroids, cyclosporine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and/or tacrolimus. History taking revealed that all lesions developed after transplantation. Times between transplantation and lesion onset ranged from 2 to 9 years (mean: 4.1 years). The most commonly associated skin disease was verruca (4), and the others were recurrent herpes simplex infection (1), actinic keratosis (1), and cutaneous B cell lymphoma (1).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the 9 renal transplant recipients with porokeratosis.

PK: porokeratosis, DSAP: disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis, CS: cyclosporine A, AZP: azathioprine, TCLM: tacrolimus, MMF: mycophenolate mofetil

Clinically, the lesions were characterized by welldemarcated hyperkeratotic papules or plaques with slightly elevated peripheries. Cases 1, 2, and 3 had less than ten lesions, and all developed in the extremities. Lesions were 5 to 8 mm in diameter and were superficial, and annular, corresponding to DSAP. Cases 4, 8, and 9 had many lesions in the extremities and almost of all were small and superficial, corresponding to DSAP (Fig. 1). Lesions of the trunk or neck presented as large, distinct hyperkeratotic plaque, corresponding to PK Mibelli (Fig. 2). Cases 5, 6 and 7 had one or two plaques several centimeters in diameter with a highly raised periphery, corresponding to PK Mibelli.

Fig. 1. Multiple erythematous annular papules and plaques with a hyperkeratotic border on the left lower leg of case 4.

Fig. 2. Two large erythematous annular plaques and a small plaque on the posterior side of the neck of case 9.

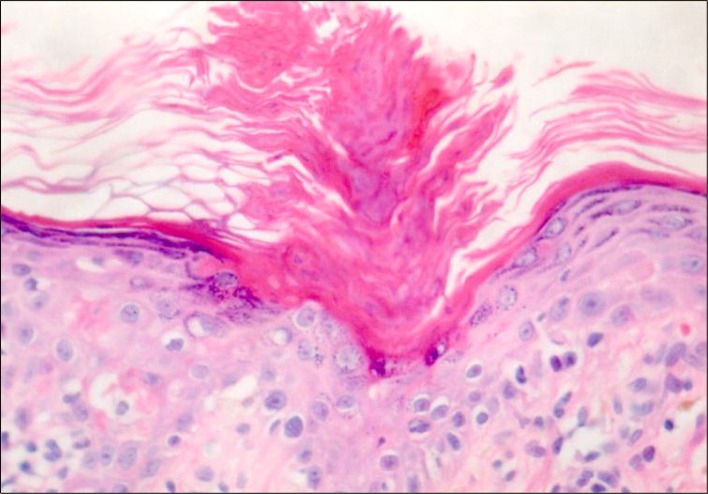

Histopathologically, lesions commonly showed a keratin-filled invagination of the epidermis with a central raised parakeratotic column, the so-called cornoid lamella. In PK Mibelli, this invagination extended downward at a sleeper angle than that observed in DSAP (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The cornoid lamella arises from a small indentation in the epidermis and extends like a thin column through the entire stratum corneum, and the underlying granular cell layer is diminished (H&E, × 400).

Three patients (cases 1, 2 and 8) were treated with imiquimod. In one patient (case 2) only the lesions improved slightly initially, but there was no significant overall change. The other patients refused treatment. No malignant change was observed during follow-up visits which ranged from 1 to 5 years.

DISCUSSION

Although the mechanism linking immunosuppression and PK remains unclear, there is growing evidence suggests that immunosuppression may give rise to a loss of immunosurveillance, which allows the proliferation of abnormal keratinocyte clones in PK lesions. This suggestion is supported by immunohistochemical studies that revealed defective expressions of HLA-DR antigens by epidermal Langerhans cells in the lesions of PK12. If this is the case, this could lead to the uninhibited expansion of mutant clones of epidermal keratinocytes, which corresponds with the clinical development of PK3,13

PK development after organ transplantation is by far the commonest type of immunosuppressionassociated PK, and this is most common after renal transplantation14. The delay between organ transplantation and the appearance of PK ranges from 4 months to 14 years according to published reports, with an average of 4~5 years2. In the present study, the average delay was also 4.1 years. It has been reported that the incidence of PK after renal transplantation varies from 0.38%7 to 10.86%8. Herranz et al8 mentioned that result discrepancies might be explained, in part, by the fact that the clinical picture of PK is easily overlooked by physicians. Immunosuppressant protocol differences might also explain these different incidences, though this suggestion is substantially unsupported 298 patients have undergone renal transplantation at our hospital over the past 6 years, and thus, we would estimate the incidence of PK to be approximately 3%. During this 6-year period, PK was constantly detected among renal transplant patients, and no significant changes were made to the immunosuppressive regimens used.

According to a study by Herranz et al8, the most common clinical pattern of PK has mixed characteristics of PK Mibelli and the superficial disseminated forms, that is, a few stable, less prominent lesions were scattered over sun-exposed areas of limbs. However, the definition of 'mixed characteristics' is unclear, and thus, we were unable to determine this terms means that DSAP and PK Mibelli coexist. In the present study, three cases (cases 4, 8, and 9) of the 9 cases enrolled showed coexisting PK Mibelli and DSAP, which prevents our confirming the dominant clinical variant of PK after renal transplantation. Further studies are required to elucidate this issue.

The premalignant potential of PK in immunocompetent patients has been well documented, as squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, or Bowen's disease arise in approximately 7% of reported cases15,16,17. This high incidence is probably related to chromosomal instability in fibroblasts and to the existence of abnormal clones in the epidermis of lesions. Interestingly, the frequency of squamous cell carcinoma has been estimated to be 40 to 250 times higher in renal transplant recipients than in the general population18. In addition to immunosuppressive agents, human papilloma virus infection and exposure to sunlight are risk factors of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients18,19. Because squamous cell carcinoma is much more aggressive and more frequently metastasizes in transplant recipients than in the general population, PK development after renal transplantation must be carefully followed up18,20. All of the patients in this study were followed-up for 1 to 5 years, but no malignant change was observed.

Physical destruction of lesions by electrodessication, cryotherapy, or carbon dioxide laser treatment is an effective therapy for PK, though these treatments have undesirable potentials for scarring and depigmentation. More superficial lesions may response temporarily to topical retinoids or photodynamic therapy21,22, and imiquimod (Aldara®; 3M, Loughborough, UK) was recently reported to be an effective treatment for PK23. However, in the present study, the single patient treated by imiquimod showed little improvement. Previous authors concur with the view that PK lesions in transplanted patients should be treated to prevent the development of squamous cell carcinoma20.

In conclusion, PK in renal transplant recipients can show coexistent clinical variants. Further studies on this topic are needed, and physicians should strive to avoid understanding PK in renal transplant recipients.

References

- 1.Wolff-Schreiner EC. Porokeratosis. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hil; 2003. pp. 532–537. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanitakis J, Euvrard S, Faure M, Claudy A. Porokeratosis and immunosuppression. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:459–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manganoni AM, Facchetti F, Gavazzoni R. Involvement of epidermal Langerhans cells in porokeratosis of immunosuppressed renal transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:799–801. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)80275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raychaudhur SP, Smoller BR. Porokeratosis in immunosuppressed and nonimmunosuppressed patients. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:781–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb04242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lugo-Janer G, Sanchez JL, Santiago-Delpin E. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of skin diseases in kidney transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:410–414. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanitakis J, Euvrard S, Claudy A. Porokeratosis in organ transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:144–146. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.109859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen EB, Komorowski RA, Clowry LJ. Cutaneous complications in renal transplant recipients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;88:32–37. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/88.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herranz P, Pizarro A, De Lucas R, Robayna MG, Rubio FA, Sanz A, et al. High incidence of porokeratosis in renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:176–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HW, Kim KJ, Lee MW, Choi JH, Moon KC, Koh JK. A case of porokeratosis following heart transplantation. Korean J Dermatol. 2004;42:1192–1194. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song JY, Kim CW, Kim HO. A case of porokeratosis developing after immunosuppression therapy in renal transplant patient. Korean J Dermatol. 2002;40:224–226. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho YH, Hann SK, Park YK. A case of disseminated superficial porokeratosis in immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipient. Korean J Dermatol. 1992;30:539–542. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sontheimer RD, Bergstresser PR, Gailiunas P, Jr, Helderman JH, Gilliam JN. Perturbation of epidermal Langerhans cells in immunosuppressed human renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1984;37:168–174. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198402000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imakado S, Otsuka F, Ishibashi Y, Ohara K. Abnormal DNA ploidy in cells of the epidermis in a case of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:331–332. doi: 10.1001/archderm.124.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanatakis J. Porokeratosis. In: Euvrard S, Kanitaki J, Claudy A, editors. Skin disease after organ transplantation. Montrouge: John Libbery Eurotext; 1998. pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasson M, Krain AD. Porokeratosis and cutaneous malignancy. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:339–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anzai S, Takeo N, Yamaguchi T, Sato T, Takasaki S, Terashi H, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma in a renal transplant recipient with linear porokeratosis. J Dermatol. 1999;26:244–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1999.tb03465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otsuka F, Someya T, Ishibashi Y. Porokeratosis and malignant skin tumors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1991;117:55–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01613197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penn I. Skin disorders in organ transplant recipients. External anogenital lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:221–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrandiz C, Fuente MJ, Ribera M, Bielsa I, Fernandez MT, Lauzurica R, et al. Epidermal dysplasia and neoplasia in kidney transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:590–596. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silver SG, Crawford RI. Fatal squamous cell carcinoma arising from transplant-associated porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:931–933. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)00469-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nayeemuddin FA, Wong M, Yell J, Rhodes LE. Topical photodynamic therapy in disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:703–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agrawal SK, Gandhi V, Madan V, Bhattacharya SN. Topical tretinoin in Indian male with zosteriform porokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:919–920. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison S, Sinclair R. Porokeratosis of Mibelli: successful treatment with topical 5% imiquimod cream. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:281–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2003.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]