Abstract

Corals are the marine organism that belongs to the phylum Cnidaria, and are one of the common causes of superficial injury in the marine environment. In addition to acute reactions such as burning or stinging pain and erythema, coral injuries may present with complications such as foreign body reactions, bacterial infections, and/or localized eczematous reactions. A 23-year-old male presented with an erythematous edematous tender patch with centrally grouped vesicles on the left ankle; the injury had occurred during skin-scuba diving 2 days before. A biopsy of the lesion treated with hematoxylin-eosin stain showed epidermal necrosis with subepidermal blisters and neutrophilic panniculitis. Herein we report a case of cellulitis caused by the nematocyst stings of corals.

Keywords: Cellulitis, Coral

INTRODUCTION

One of the most common injuries in the marine environment is the stings caused by Cnidarians including jellyfish, the Portuguese man of war, hydroids, sea anemones, and coral1,2. Corals are a member of the class Anthozoa, which is composed of many calcified polyps that containing tentacles with nematocysts, venom-filled cells that are responsible for stings and lacerations1,3. Coral injuries present with acute reactions such as pain, erythema, and swelling and may also be complicated by foreign-body reactions, secondary bacterial infections, and/or localized eczematous reactions1.

Herein we report a case of cellulitis associated with coral injury of the ankle of 23-year-old man who had been wounded during skin-scuba diving in island of Hainan, China 2 days before his presentation to our clinic.

CASE REPORT

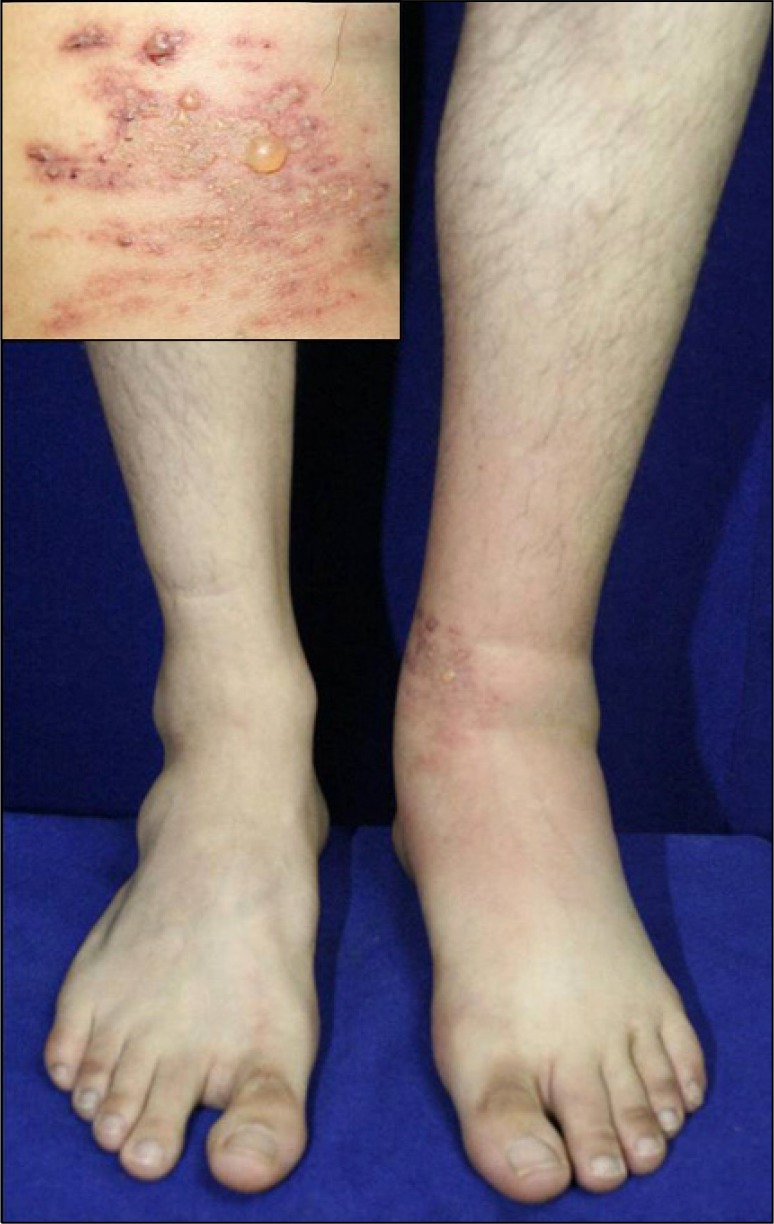

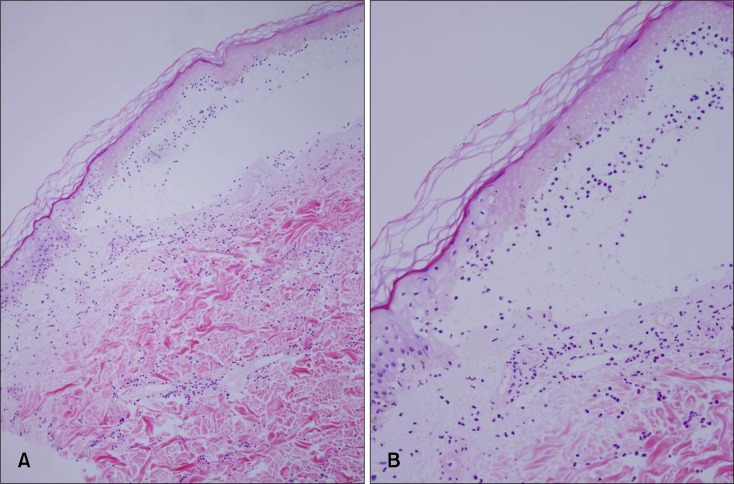

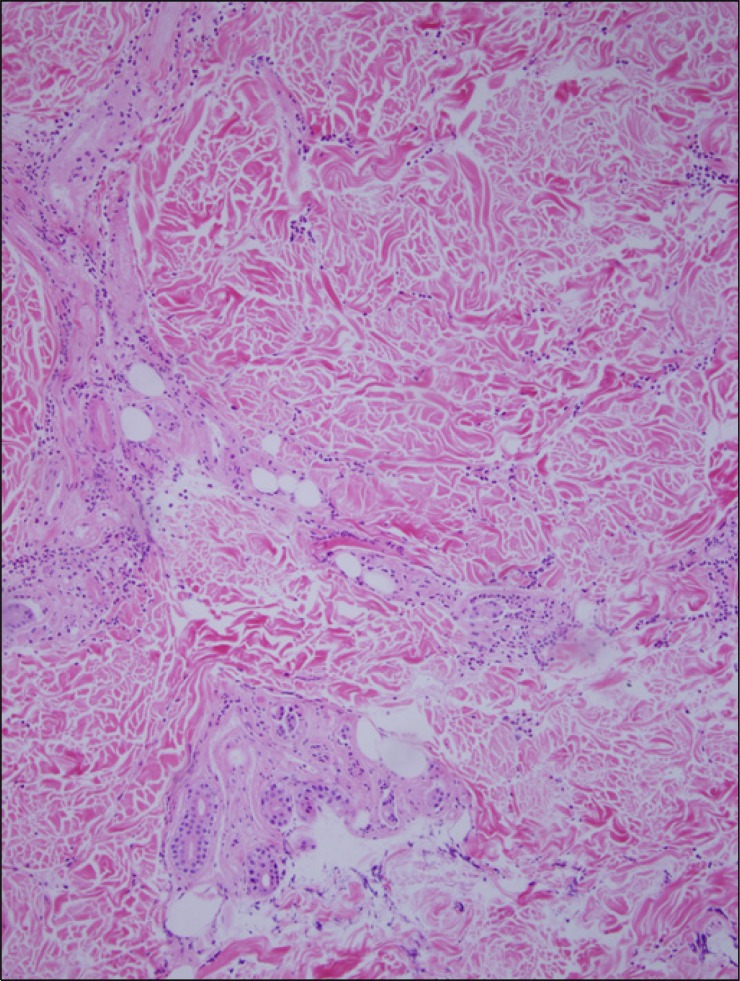

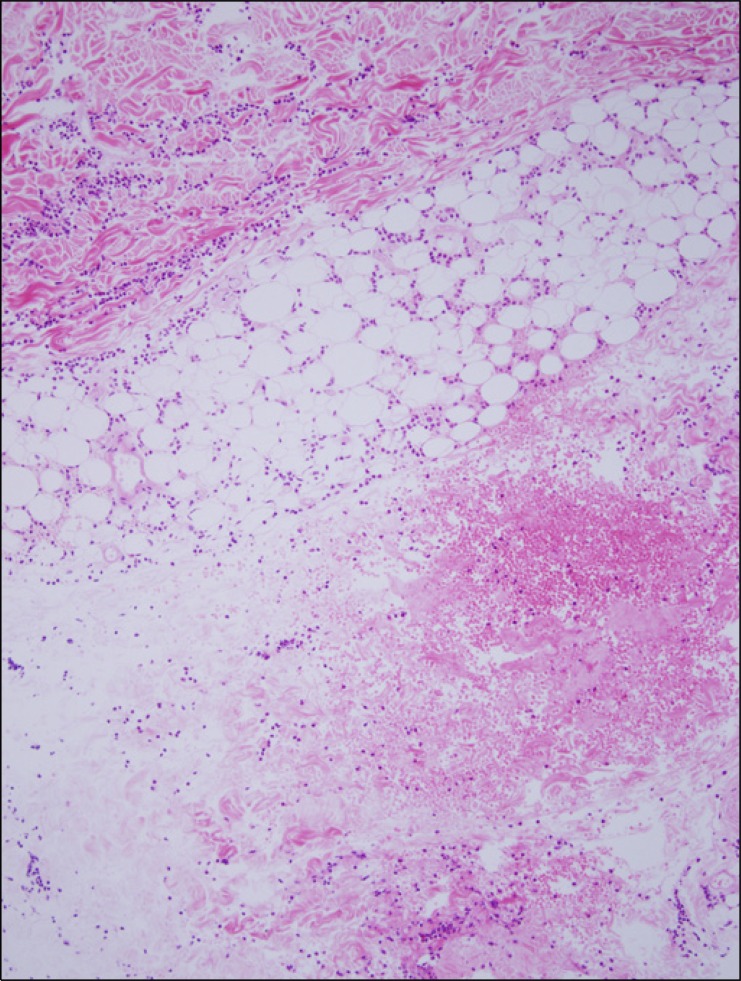

A 23-year-old man presented with an erythematous edematous patch with centrally grouped vesicles on the left ankle (Fig. 1). The skin lesion occurred following a coral injury while he was skin-scuba diving at the island of Hinan, China 2 days prior to his presentation. This was associated with stinging pain and mild itching. He stated that the accident had occurred near the coral reef and at the time, he had felt stinging pain on his left ankle which was not covered by the diving suit. On physical examination, there were no remarkable findings including a normal body temperature except for the skin lesion. His past medical history was not significant. Histopathologic findings revealed the extensive epidermal necrosis with subepidemal blisters and neutrophils in the blister cavity (Fig. 2) and interstitial, perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory cell infiltration throughout the dermis (Fig. 3). There was also panniculitis predominantly infiltrated with neutrophils and some eosinophils and lymphohistiocytes without the evidence of foreign body granulomas (Fig. 4). Radiological examination of his left ankle showed non-specific findings and no foreign body materials, and laboratory testing showed only leukocytosis including neutrophilia with a mildly elevated ESR. We did not perform a bacterial culture and sensitivity test.

Fig. 1. Erythematous edematous patch with central grouped vesicles on the left ankle.

Fig. 2. (A) Histopathologic findings show extensive epidermal necrosis with subepidermal blisters (H&E, ×10). (B) There are some neutrophils within the blister cavity (H&E, ×20).

Fig. 3. Mild to moderate interstitial, perivascular, and periadnexal inflammatory cell infiltrate of neurophils in the dermis (H&E, ×10).

Fig. 4. Panniculitis mainly infiltrated with neutrophils, some eosinophils, and lymphohistiocytes (H&E, ×10).

Because his vaccination history was uncertain, we gave him an anti-tetanus immunoglobulin injection and treated him with systemic steroids in combination with antibiotics (a 1st generation cephalosporin for 1 week and a 3rd generation cephalo sporin for the following 2 weeks). For local therapy, we applied mupirocin ointment and a topical steroid cream. After 3 days of treatment, the pain and erythema were both improved but the swelling on the left lower leg was still present. So we changed the antibiotic regimen to levofloxacin for 7 days; afterwards, his symptoms began to resolve slowly. We have observed him for 5 months and his skin lesion is almost completely resolved without any signs of delayed hypersensitivity reactions.

DISCUSSION

Coral is an aquatic organism that belongs to the phylum Cnidaria1,2. It is composed of many calcified polyps that contain tentacles with venom-filled cells called nematocysts1,3. There are two types of coral injuries: stings and lacerations. Of the two, stings are caused injected nematocysts which contain toxins like calcium carbonate and are generated from hard coral reef structures2. The coral injuries occur most commonly on forearms, elbows, knees, and other areas unprotected by gloves or the diving suits which are used for sports diving and other marine-related activities. The initial responses of coral injuries including stinging pain, erythema, and swelling occur immediately to within several hours around the wound4. These symptoms result from coral poisoning. Systemic symptoms such as low grade fever also may be present but do not necessarily indicate an infection4.

Coral injuries can be complicated with foreign body reactions, localized eczematous reactions, and/or secondary bacterial infections1. Foreign body reactions, which result in granuloma formation, may occur because of retained bits of calcareous material and proteins from injected nematocysts5. A delayed and persistent contact dermatitis has also been reported to occur following coral stings which occur off the eastern coastline of the Red Sea. In that report, the shiny and lichenoid coalescent papules with severe itching developed 3 weeks later after injuries which occurred to people who had a history of seafood allergy, atopic dermatitis, or previous contact with coelenterates6,7. The delayed reactions to cnidarians stings are not uncommon and may occur 2~14 days after the occurrence of a sting injury2,8. It usually presents as a erythematous papular or papulonodular eruption with severe itching at the same site of the stings2. It takes several weeks to heal and may respond to topical or systemic steroids in combination with antihistamines2,8. Injuries that occur in the marine environment can be also infected with marine organisms such as Streptococcus species, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Mycobacterium marinum, Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio vulnificus, or Vibrio parahaemolyticus which are the most common pathogens isolated from seawater and marine wounds3. Therefore, coral injury accompanied with a secondary bacterial infection may lead to cellulitis with ulceration and tissue necrosis. As all the factors mentioned above are responsible for the slow healing of a coral injury, we need to deal with the appropriate management for each of them.

In our case, no foreign body materials of his left ankle were found on physical and radiological examination. However, there were clinical and laboratory findings of cellulitis including redness, swelling, local heating, tenderness, and leukocytosis with neutrophilia and an elevated ESR. In addition, the histopathologic findings showed epidermal necrosis with diffuse infiltrate, composed mainly of neutrophils that extended throughout the dermis and into the subcutaneous fat. An initial outpatient therapy for secondary bacterial infection in the marine environment should be targeted against Vibrio species, which includes ciprofloxacin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. In the case of inpatients, parenteral antibiotics appropriate for initial therapy include cefotaxime, ceftazidime, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, and tobramicin. In our case, we treated him with cephalosporin in combination with systemic corticosteroids for 3 weeks. Although the erythema and pain were getting better, the swelling on the leg was not. We then replaced cephalosporin with levofloxacin, a quinolone derivative. As for local therapy, mupirocin ointment and topical corticosteroids were applied along with aspiration and saline wet dressing of vesicles.

According to previous reports, the complete healing period varies from 1 week to 15 weeks1,4,8. It may be more delayed if a secondary infection or delayed hypersensitivity reaction occurred. In our case, the acute reaction accompanied with cellulitis began to subside slowly and we considered the possibility of a delayed reaction; we arranged for follow up observation. We report a case of cellulitis caused by a coral injury which revealed extensive epidermal necrosis with subepidermal blisters and neutrophilic panniculitis on histopathologic examination.

References

- 1.Scharf MJ, Daly JS. Bites and stings of terrestrial and aquatic life. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. pp. 2270–2271. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke WA. Cnidarians and human skin. Dermatol Ther. 2002;15:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zoltan TB, Taylor KS, Achar SA. Health issues for surfers. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:2313–2317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auerbach PS, Burgess GH. Injuries from nonvenomous aquatic animals. In: Auerbach PS, editor. Wilderness medicine [Internet] 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007. [cited 2008 May 2]. Available from: http://www.mdconsult.com/das/book/body/93629417-2/0/1483/692.html?tocnode=54238530&fromURL=692.html#4-u1.0-B978-0-323-03228-5..50077-X--cesec56_4329. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habif TP. Dermatitis associated with swimming. In: Habif TP, editor. Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy. 4th ed. Chile: Mosby; 2004. pp. 539–543. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miracco C, Lalinga AV, Sbano P, Rubegni P, Romano C. Delayed skin reaction to Red Sea coral injury showing superficial granulomas and atypical CD30+ lymphocytes: report of a case. Br J Der matol. 2001;145:849–851. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Addy JH. Red sea coral contact dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:271–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb04636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagregorio G, Guillet G. Delayed dermal hypersensitivity reaction to coral. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:534–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]