Abstract

Subcortical structural alterations have been implicated in the neuropathology of schizophrenia. Yet, the extent of anatomical alterations for subcortical structures across illness phases remains unknown. To assess this, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used to examine volume differences of major subcortical structures: thalamus, nucleus accumbens, caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, amygdala and hippocampus. These differences were examined across four groups: i) healthy comparison subjects (HCS, n=96); ii) individuals at high risk (HR, n=21) for schizophrenia; iii) early-course schizophrenia patients (EC-SCZ, n=28); and iv) chronic schizophrenia patients (C-SCZ, n=20). Raw gray matter volumes and volumetric ratios (volume of specific structure / total gray matter volume) were extracted using automated segmentation tools. EC-SCZ group exhibited smaller bilateral amygdala volumetric ratios, compared to HCS and HR subjects. Findings did not change when corrected for age, level of education and medication use. Amygdala raw volumes did not differ among groups once adjusted for multiple comparisons, but the smaller amygdala volumetric ratio in EC-SCZ survived Bonferroni correction. Other structures were not different across the groups following Bonferroni correction. Smaller amygdala volumes during early illness course may reflect pathophysiologic changes specific to illness development, including disrupted salience processing and acute stress responses.

Keywords: Early course, Amygdala, Illness stage

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe chronic illness associated with psychosis, thought disorganization and cognitive impairment (Tamminga, 2009). The significant functional decline of patients and 0.55% global lifetime prevalence (Saha et al., 2005) make understanding schizophrenia neurobiology important from both scientific and clinical perspectives. While cortical dysfunction, specifically in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the temporal cortex, is thought to be responsible for cognitive deficits and hallucinations (Barch et al., 2003; Deserno et al., 2012; Jardri et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2005), complementary studies have increasingly documented significant impairments in emotion processing, with nodes of dysfunction located in subcortical regions (Dowd and Barch, 2010; Nielsen et al., 2012; Pinkham et al., 2011; Schlagenhauf et al., 2014). For instance, abnormal amygdala function in response to emotional faces and decreased blood-oxygen level dependent (BOLD) activation in the ventral striatum during reward processing have been demonstrated in patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls (Anticevic et al., 2012b; Pinkham et al., 2011; Schlagenhauf et al., 2014). Such functional alterations are likely linked to structural abnormalities of subcortical nuclei, and these local changes in structure and function may ultimately be reflected in the disruption of large-scale neural networks in patients with schizophrenia (Anticevic et al., 2014a; Cole et al., 2011; Meda et al., 2009).

Schizophrenia symptoms are hypothesized to reflect dynamical changes in structure and function over the illness course (Douaud et al., 2009; Mane et al., 2009). Indeed, structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in humans have revealed prefrontal and temporal cortical thinning among patients with schizophrenia, compared to healthy controls (Nesvag et al., 2008; Voets et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2010), even at early stages of illness (Narr et al., 2005a; Narr et al., 2005b). Examination of structural abnormalities of subcortical nuclei has yielded mixed findings. In general, meta-analyses of subcortical regions have suggested that patients with schizophrenia tend to have decreased gray matter volumes of subcortical regions, compared to healthy controls (Bora et al., 2011; Ellison-Wright et al., 2008; Haijma et al., 2013; Shepherd et al., 2012). Temporal lobe structures, including the amygdala and hippocampus, have been shown to be smaller in patients with schizophrenia, compared to control subjects (Anderson et al., 2002; Gur et al., 2000; Marsh et al., 1994; Namiki et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008) (though see: (Killgore et al., 2009; Sanfilipo et al., 2000)). Thalamic volumes have also been shown to be smaller in patients with schizophrenia, including at first-episode (Ananth et al., 2002; Andreasen et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2007; Staal et al., 2001). Striatal (caudate and/or putamen) findings have been mixed, with studies demonstrating increased, decreased, or similar volumes in patients with schizophrenia, compared to control subjects (Glahn et al., 2008; Oertel-Knochel et al., 2012; Okugawa et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008). Finally, inclusion of subcortical structural abnormalities in a statistical model of gray matter changes yielded accurate classification of subjects with or without schizophrenia, highlighting the importance of understanding subcortical structural changes in disease states (Kawasaki et al., 2007).

Differences in subcortical anatomical findings may reflect the heterogeneity of schizophrenia disease presentation. Illness duration, in particular may be a factor that significantly moderates findings (Insel, 2010), and examining patients at different illness stages may lead to more specific information on changes in subcortical structures. We hypothesized that stages of illness may differentially affect subcortical regions. Specifically, we a priori hypothesized that the hippocampus, amygdala and nucleus accumbens, regions involved in sensory and emotion processing, may be altered in the early phase of illness when initial acutely psychotic symptoms are prominent. Those regions involved in motor processes, such as the globus pallidus, caudate nucleus and putamen, were hypothesized to be affected later in disease when negative symptoms dominate. Finally, a region such as the thalamus was hypothesized to be structurally abnormal across all phases of illness, as it is involved in an array of functions, including both sensory and motor processes. To test these hypotheses we employed a cross-sectional clinical design to quantify differences in subcortical gray matter volume across disease stages. Any other examinations of the effect of illness stage on subcortical regional volume were done in a post hoc, exploratory analysis.

Total gray matter volume was controlled for to account for decreases in overall gray matter volume, a finding well-documented in both chronic and first-episode schizophrenia (Andreasen et al., 2011; Bose et al., 2009; Glahn et al., 2008; Gur et al., 1999; Hulshoff Pol et al., 2002; Vita et al., 2012). White matter changes have also been documented in schizophrenia (Bose et al., 2009; Ho et al., 2003; Hulshoff Pol et al., 2002; Pasternak et al., 2012), but only gray matter was corrected for because of the differential trajectories of progressive gray versus white matter changes, likely reflecting different pathophysiologic processes (Bose et al., 2009; Hulshoff Pol et al., 2002). Gray matter volumes of major subcortical structures were analyzed in healthy subjects (HCS), subjects at high-risk (HR) for schizophrenia, subjects in the early-course of schizophrenia (EC-SCZ), and subjects with chronic schizophrenia (C-SCZ). We specifically focused on the thalamus, caudate nucleus, putamen, globus pallidus (GP), nucleus accumbens (NAc), amygdala and hippocampus. Across all examined regions, results revealed a significant group effect only for amygdala volumetric ratios corrected for whole-brain gray matter differences, which were driven by a specific reduction in amygdala volumes in the early course of illness.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

All participants were recruited from the clinics and community of China Medical University, Shengyang, China. The clinical samples (C-SCZ, n=20; EC-SCZ, n=28; HR, n=21) were recruited from outpatient clinics of the Department of Psychiatry, First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University. All patients met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, schizophreniform or brief psychotic disorder, exclusive of any other Axis I diagnosis. Two independent psychiatrists trained to use the Chinese translation of the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) for DSM-IV (First, 2001; http://www.scid4.org/trans.html) assessed those patients older than 18 years of age. Those younger than 18 were assessed using the Schedule for the Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL (Kaufman et al., 1997)). Of the 48 patients with schizophrenia, 28 were within 1 year of their initial clinical presentation (defined as early course, EC-SCZ, mean=4.27 months of illness duration). This time frame was defined as the difference between the age of first evident symptoms (as reported by participants and confirmed with medical records and family) and the age at the time of scanning. EC-SCZ patients were then followed and confirmed to meet DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia by trained clinicians. In contrast, C-SCZ patients met diagnostic criteria for at least 12 consecutive months (mean=64.45 months). While the distinction between EC-SCZ and C-SCZ is certainly arbitrary, we have employed this definition here for the purposes of a cross-sectional study, with additional analyses using duration of illness as a continuous measure. Of note, the EC-SCZ group does not necessarily encompass only those experiencing a first-episode. However, there is a large literature on neurobiological differences in first-episode schizophrenia, and the criteria for recruitment and average duration of illness for the EC-SCZ group in our study encompasses the time course of those recruited with first-episode in other studies (Gelber et al., 2004; Gupta et al., 1997; Lieberman et al., 2005; Nenadic et al., 2015; Rais et al., 2008; Wheeler et al., 2014). HR subjects were comprised of offspring of individuals with schizophrenia (at least one parent), and who were not past the age of peak illness risk (<30 y/o) – these subjects therefore still had potential to develop illness. Of note, HR subjects were unrelated to any of the other clinical groups. Exclusion criteria for patients included current nicotine, alcohol or drug abuse/dependence, though subjects were allowed to have a history of nicotine and/or alcohol use. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS (Overall and Gorham, 1962)) was used to evaluate patient symptoms. 95% of chronic patients and 43% of early course patients were taking antipsychotics at the time of data acquisition, and all medications and dosing were converted to chlorpromazine (CPZ) equivalents (Andreasen et al., 2010) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics (mean ± S.D.). HCS = healthy comparison subjects; HR = high risk subjects; EC-SCZ = early course schizophrenia patients; C-SCZ = chronic schizophrenia patients. BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; M, Mean; SD, Standard Deviation; CPZ, chlorpromazine equivalents; df, degrees of freedom. Age, education levels, and age at diagnosis are expressed in years; duration of illness is expressed in months. The educational attainment was used as a proxy for occupation status (SES) of the participants’ parents and was scored according to The International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI)(Ganzeboom and Treiman, 1996). CPZ equivalents were calculated using recently revised approaches(Andreasen et al., 2010). No participants had current alcohol/drug use, or past history of drug dependence.

| Demographic | HCS (n=96) | HR (n=21) | EC-SCZ(n=28) | C-SCZ(n=20) | p-value (F/T-Value or Chi-Square, df) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 28.84 ± 10.51 | 19.95 ± 5.24 | 25.00 ± 9.70 | 31.43 ± 8.20 | <0.001*** (6.73, 161) |

| Gender (% male) | 45 | 57 | 43 | 45 | 0.75 (1.23, 3) |

| Mother’s Education Attainment | 36.67 ± 21.89 | 31.26 ± 15.14 | 34.00 ± 19.72 | 37.06 ± 22.48 | 0.38 (0.77, 161) |

| Father’s Education Attainment | 37.63 ± 22.69 | 30.22 ± 14.43 | 34.54 ± 19.39 | 28.79 ± 18.25 | 0.28 (1.28, 161) |

| Subject’s Education (# of yrs) | 14.79 ± 3.11 | 12.70 ± 2.83 | 11.54 ± 3.02 | 11.48 ± 3.52 | <0.001*** (13.06, 161) |

| Handedness (% right) | 88.54 | 71.43 | 78.57 | 90.00 | 0.44 (8.97, 9) |

| Medication CPZ equivalents | N/A | N/A | 96.40 ± 71.33 | 240.00 ± 132.22 | <0.01** (2.57, 46) |

| Percent Treated | N/A | N/A | 43.00 | 95.00 | <0.001*** (13.86, 46) |

| BPRS Total Symptoms | N/A | 18.11 ± 0.46 | 36.67 ± 15.68 | 25.56 ± 10.58 | <0.001*** (14.42, 46) |

| Duration of Illness (months) | N/A | N/A | 4.27 ± 3.20 | 64.45 ± 38.26 | <0.001*** (8.32, 46) |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

Healthy comparison subjects (HCS, n=96) were recruited at China Medical University through advertisement, and mean-matched to the clinical samples (HR, EC-SCZ, C-SCZ) by age, sex, ethnicity, handedness and parental socio-economic status (represented using parental education attainment) though not individual educational attainment. HCS also underwent a clinical evaluation with SCID or K-SADS-PLS by a trained psychiatrist to rule out a current or lifetime Axis I disorder, history of medical or neurological disorders, and history of psychotic, mood or other Axis I disorders in first-degree relatives (assessed by detailed family history). All participants were excluded based on the following criteria: i) History of neurological conditions (e.g. epilepsy, migraine, head trauma, loss of consciousness); ii) Any MRI contraindications; and iii) Any concomitant major medical disorder. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, as approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University and Yale University.

2.2. Image acquisition

All images were acquired on a GE Signa HDX 3.0T magnetic resonance (MR) scanner. High-resolution images were collected with a T1-weighted, 3D fast spoiled gradient-echo (FSPGR) sequence (TR/TE=7.1/3.2 ms, flip angle=13°, field of view=24×x24 cm2, 176 slices, voxel size=1 mm3). Resting state BOLD data collected in the same subjects in the same session were analyzed as part of a previous study (Anticevic et al., 2014b).

2.3. Structural volume analyses

For each individual subject, images were skull-stripped and segmented using fully automated FreeSurfer software (Segonne et al., 2004). Gray matter voxels were extracted based on each subject’s unique anatomy using FreeSurfer. While FreeSurfer has allowed for efficient, automated segmentation, isolation of smaller regions, such as the amygdala, have been shown to have variable accuracy, necessitating the need for manual inspection (Fischl et al., 2002). All results were visually inspected for quality by a trained rater (AA) and visualized qualitatively across samples in FSLView (Smith et al., 2004) (Fig. 1). Images were discarded if there was evidence for gross anatomical segmentation errors. All of the final segmentations were deemed of sufficient quality for inclusion in the analyses in terms of within-group anatomical overlap. Total gray matter volume was calculated for each subject. For each region of interest (thalamus, NAc, caudate nucleus, putamen, GP, amygdala and hippocampus), anatomic boundaries were defined bilaterally through FreeSurfer segmentation (Fischl et al., 2002; Fischl et al., 2004), and inspected for quality by a trained rater (AA). The right and left volumes of each region were combined and analyzed jointly (as there were no hemispheric interactions). Absolute individual regional volumes (mm3) for each region, as well as the relative mean volume (regional volume / total gray matter) were calculated for each subject and entered into 2nd level analyses as described in Section 2.4. Here the relative mean volume for each structure provided a way of identifying specific regional changes while controlling for total gray matter volume changes on an individual subject basis.

Fig. 1.

Probabilistic maps across groups and subcortical structures. Probabilistic structural maps across all four groups: (A) healthy comparison subjects (HCS), (B) high-risk subjects (HR), (C) early-course schizophrenia patients (EC-SCZ), (D) chronic schizophrenia patients (C-SCZ). Structures are shown in columns. The statistical maps indicate the probability of overlap across all subjects within a given sample, ranging from 0% to 100% overlap. The overall subcortical segmentation for each group was highly comparable in terms of within-group anatomical overlap, providing strong quality assurance of FreeSurfer-derived segmentation. Note that while these data reflect results after registration, and some of the differences across groups may be minimized, gross errors in segmentation would still be seen because non-linear deformation algorithms were not used (see Methods). Specifically, linear registration will by definition not obscure relative shape and alignment differences across groups.

2.4. Statistical methods

To quantify the effect of illness stage on each brain region, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were calculated for each individual region with Group as a four-level factor (HCS, EC-SCZ, C-SCZ, HR). Either absolute individual regional volumes or relative mean volumes were dependent measures. For those ANOVAs with significant F-values, planned comparisons as described in the Introduction (EC-SCZ vs. HCS for hippocampus, amygdala and nucleus accumbens; C-SCZ vs HCS for caudate nucleus, putamen and GP; HR, EC-SCZ, C-SCZ vs. HCS for thalamus), as well as all remaining post-hoc comparisons, were examined with Fisher’s Least Significant Differences t-tests. Bonferroni correction was applied. Those demographics that were significantly different among the groups were also correlated with amygdala volumes and amygdala volume ratios. Any correlations that were significant across all groups were entered as covariates.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Demographics across groups are shown in Table 1. The age of participants significantly differed among the groups (F(3,161)=6.73, p<0.001), with post-hoc comparisons showing a significantly younger HR group (mean=19.95 years), as compared with the HCS (mean=28.84 years) and C-SCZ (mean=31.43 years). The age difference was expected given the inherent cross-sectional design of the current study. Age was statistically controlled for across all analyses. Additional post-hoc age-matched analyses such as correlation mapping were conducted to verify that reported changes were not driven by age. Educational achievement also significantly differed among groups (F(3,161)=13.06, p<0.001), with the HCS group obtaining, on average, higher educational levels. These group differences in education likely reflect the well-known epidemiologic finding indicating that schizophrenia emerges in late adolescence, likely curtailing the typical educational trajectory (Hafner et al., 1994). Given the cross-sectional study design, groups significantly differed with respect to level of medication (measured in CPZ equivalents), percent of subjects receiving treatment, BPRS symptoms, and duration of illness. A higher percent of those in the C-SCZ group received treatment, and with higher medication levels, as compared to the EC-SCZ or HR groups. Of note, these variables were controlled for statistically and did not alter reported effects. Furthermore, we conducted careful follow-up age-matched analyses to rule out neuro-maturational effects (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Correlation of age with mean volume and volumetric ratios for the amygdala. (A) Mean amygdala volume and (B) amygdala volumetric ratio as a function of age, revealing weak relationships. As evident from panel B, across the age range, the EC-SCZ group was associated with lower amygdala volumetric ratio (red data points). Correlations examined for each group separately revealed that the significance of the positive correlation was driven by the HCS group. The HR, E-SCZ and C-SCZ had non-significant correlations and negative r-values (see text for details).

3.2. Mean volumetric analyses across group

Given that there were no effects of laterality for any region, the bilateral mean volumes of each region were entered into one-way ANOVAs with group as a 4 level factor. The mean volumes of the thalamus, NAc, caudate nucleus, putamen, GP and hippocampus did not significantly differ among the four groups (all p>0.05, see Table 2, Fig. 2). Difference in mean amygdala volume were significant across the groups (F(3,161)=2.99, p=0.033), though this did not survive Bonferroni correction when correcting for comparisons across all structures. The trend towards significance of this main effect was primarily driven by the EC-SCZ group having significantly smaller bilateral amygdala volumes (3694 ± 70.86 mm3), as compared with the HCS group (3987 ± 36.23 mm3) (p=0.0002, Cohen’s d=0.69) (see Table 3 and Fig. 2). There were no significant differences between any other pairwise comparisons across any structures.

Table 2.

Mean raw volume of each subcortical region for each group, and associated one-way ANOVA (group). Mean Volume (mm3) ± S.E.M. Degrees of freedom = 161.

| Region | HCS (n=96) | HR (n=21) | EC-SCZ (n=28) | C-SCZ (n=20) | p-value (F-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thalamus | 16382 ± 142.57 | 16808 ± 267.26 | 16245 ± 272.58 | 16399 ± 328 | 0.474 (0.84) |

| NAc | 1525 ± 16.03 | 1533 ± 34.40 | 1543 ± 37.40 | 1478 ± 35.20 | 0.474 (0.84) |

| Caudate Nucleus | 8505 ± 101.3 | 8393 ± 216.6 | 8840 ± 162.8 | 8855 ± 169.5 | 0.167 (1.71) |

| Putamen | 14234 ± 113.81 | 14478 ± 299.90 | 14449 ± 245.49 | 14715 ± 309.87 | 0.536 (0.73) |

| GP | 3963 ± 31.41 | 4041 ± 64.94 | 4007 ± 79.78 | 4100 ± 52.23 | 0.448 (0.89) |

| Amygdala | 3987 ± 36.23 | 3896 ± 88.64 | 3694 ± 70.86 | 3862 ± 93.66 | 0.033* (2.99) |

| Hippocampus | 10675 ± 88.15 | 10378 ± 171.93 | 10386 ± 165.37 | 10211 ± 228.20 | 0.26 (1.35) |

| Total Gray Matter | 795049 ± 3460.14 | 780467 ± 6796.27 | 815422 ± 6156.19 | 791596 ± 8824.42 | 0.002** (5.1) |

p<0.05,

p<0.01.

Fig. 2.

Mean volumes of subcortical structures. Mean bilateral volumes (mm3) of: (A) amygdala, (B) caudate nucleus, (C) globus pallidus, (D) hippocampus, (E) nucleus accumbens, (F) thalamus, and (G) putamen across groups. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). HCS, healthy comparison subjects, HR, high-risk subjects, EC-SCZ, early-course schizophrenia, C-SCZ, chronic schizophrenia. * denotes a significant difference for the EC-SCZ group relative to the HCS group.

Table 3.

Pairwise between-group comparisons of mean raw amygdala volumes.

| Comparison | Cohen’s d | t-value | p-value (2-tailed, equal variance) | Survived Bonferroni Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCS vs. HR | 0.194 | 1.04 | 0.3 | N.S. |

| HCS vs. EC-SCZ | 0.686 | 3.79 | <0.001** | YES |

| HCS vs. C-SCZ | 0.260 | 1.39 | 0.17 | N.S. |

| HR vs EC-SCZ | 0.525 | 1.8 | 0.08 | N.S. |

| HR vs. C-SCZ | 0.083 | 0.26 | 0.8 | N.S. |

| C-SCZ vs. EC-SCZ | 0.428 | 1.45 | 0.15 | N.S. |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

N.S., not significant.

3.3. Mean volumetric ratio analyses across group

As noted, schizophrenia may be associated with overall gray matter loss that may be differential across distinct illness stages. This could fundamentally confound the mean volumetric comparisons reported above. To control for distributed loss of gray matter across the brain we next computed the ratio of each regional volume relative to overall gray matter volume. The main purpose of this analysis was to provide an explicit control for the total volume of gray matter present in each individual. This in turn allowed for an interpretation of regional reduction in the context of whole-brain alterations that may occur as a function of illness progression or neuro-maturation. As above, mean volumetric ratios (defined as the mean volume of the region of interest / total volume of gray matter) of each region were entered into one-way ANOVAs with group as a 4-level factor. The mean volumetric ratios of the thalamus, NAc, caudate nucleus, putamen, GP and hippocampus did not significantly differ among the groups (Table 4 and Fig. 3). In contrast, the mean volumetric ratio of the amygdala significantly differed across the groups (F(3,161) = 6.30, p=0.001). Again the effect was primarily driven by the EC-SCZ group as for the regional mean volume analyses. The EC-SCZ group (mean=0.0045 ± 1.0*10−4) had significantly smaller bilateral amygdala mean volumetric ratios than the HCS group (mean=0.0050 ± 4.50*10−5) (p<0.0001, Cohen’s d=0.92) and HR group (0.005 ± 1.0*10−4) (p<0.0015, Cohen’s d=0.99), which survived Bonferroni correction. While there was a trend towards significance of the EC-SCZ volumetric ratios being smaller than the C-SCZ group (p<0.05, Cohen’s d=0.7), this did not survive Bonferroni correction (Table 5). There were no significant differences between any other pairwise comparisons across any structures.

Table 4.

Mean volumetric ratio (mean volume of region (mm3) / volume of total GM (mm3)) of each subcortical region for each group, and associated one-way ANOVA (group). Mean Volumetric Ratio ± S.E.M. Degrees of freedom = 161.

| Region | HCS (n=96) | HR (n=21) | EC-SCZ (n=28) | C-SCZ (n=20) | p-value (F-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thalamus | 0.0206 ± 1.71*10−4 | 0.0207 ± 4.10*10−4 | 0.0204 ± 3.62*10−4 | 0.0211 ± 3.75*10−4 | 0.485 (0.82) |

| NAc | 0.0019 ± 1.95*10−5 | 0.0020 ± 4.79*10−5 | 0.0019 ± 4.63*10−5 | 0.0019 ± 5.10*10−5 | 0.372 (1.05) |

| Caudate Nucleus | 0.0107 ± 1.29*10−4 | 0.0108 ± 2.83*10−4 | 0.0108 ± 1.99*10−4 | 0.0112 ± 2.64*10−4 | 0.404 (0.98) |

| Putamen | 0.0179 ± 1.26*10−4 | 0.0186 ± 4.19*10−4 | 0.0177 ± 2.77*10−4 | 0.0186 ± 4.77*10−4 | 0.049* (2.68) |

| GP | 0.0050 ± 4.30*10−5 | 0.0052 ± 9.56*10−5 | 0.0049 ± 1.01*10−4 | 0.0052 ± 1.06*10−4 | 0.05* (2.66) |

| Amygdala | 0.0050 ± 4.50*10−5 | 0.0050 ± 1.0*10−4 | 0.0045 ± 1.0*10−4 | 0.0049 ± 1.0*10−4 | 0.001** (6.3) |

| Hippocampus | 0.0134 ± 1.0*10−4 | 0.0133 ± 2.0*10−4 | 0.0128 ± 2.0*10−4 | 0.0129 ± 3.0*10−4 | 0.11 (2.02) |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

Fig. 3.

Mean volumetric ratios of subcortical structures. Mean volumetric ratios of: (A) amygdala, (B) caudate nucleus, (C) globus pallidus, (D) hippocampus, (E) nucleus accumbens, (F) thalamus, and (G) putamen across groups. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). HCS, healthy comparison subjects, HR, high-risk subjects, EC-SCZ, early-course schizophrenia, C-SCZ, chronic schizophrenia. ** denotes a significant difference for the EC-SCZ group relative to the HCS and HR groups. Note: the amygdala effect for this analysis survived Bonferroni correction across all comparisons.

Table 5.

Pairwise between-group comparisons of mean amygdala volumetric ratios.

| Comparison | Cohen’s d | t-value | p-value (2-tailed, equal variance) | Survived Bonferroni Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCS vs. HR | 0.045 | 0.24 | 0.8108 | N.S. |

| HCS vs. EC-SCZ | 0.923 | 5.1 | <0.0001*** | YES |

| HCS vs. C-SCZ | 0.204 | 1.09 | 0.28 | N.S. |

| HR vs. EC-SCZ | 0.992 | 3.4 | <0.0015** | YES |

| HR vs. C-SCZ | 0.189 | 0.59 | 0.56 | N.S. |

| C-SCZ vs. EC-SCZ | 0.696 | 2.36 | <0.025* | N.S. |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

N.S., not significant.

3.4. Correlations between volume and demographic characteristics

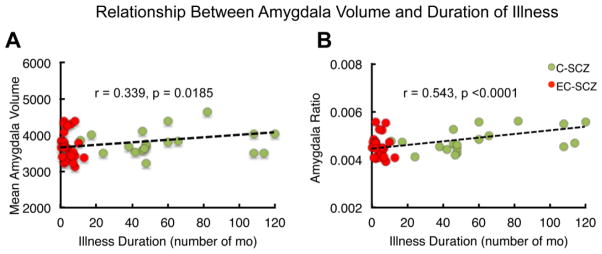

Because the four groups significantly differed in age, amount of education, and CPZ equivalents, amygdala volumes were correlated with these demographics to test for presence of any relationships. Amygdala raw volumes were not significantly correlated with age (r=−0.0336, p=0.67, Fig. 4), level of education (r=0.1111, p=0.16), or CPZ equivalents (r=0.1990, p=0.37). Amygdala volumetric ratios showed a significant correlation with age (r=0.162, p<0.04, Fig. 4). Examination of the groups separately showed that this was mostly driven by the HCS group (r=0.332, p=0.001); the relationship differed in direction and was non-significant for patient groups (HR(r=−0.161, p=0.50), EC-SCZ(r=−0.216, p=0.279), C-SCZ(r=−0.0407, p=0.87)). Because amygdala ratios were not significantly correlated with age within each group no further correction was applied to second-level analyses. Amygdala ratios were not significantly correlated with level of education (r=0.0608, p=0.44) or CPZ equivalents (r=0.1903, p=0.40). However, both amygdala raw volumes and volumetric ratios were significantly correlated with duration of illness ((r=0.339, p=0.0185) and (r=0.543, p<0.0001), respectively)) (Fig. 5). Neither amygdala raw volumes nor ratios were significantly correlated with BPRS total scores (r=−0.074, p=0.571; r=−0.1274, p=0.302). In addition, examination of gender effects revealed a non-significant interaction of gender with amygdala volume and a non-significant main effect of gender (both p>0.05).

Fig. 5.

Correlation of illness duration (number of months) with mean volume and volumetric ratios of the amygdala. Illness duration was significantly positively correlated with both mean amygdala volume (A) and amygdala volumetric ratio (B). Correlation reflects the significantly smaller amygdala volumes and ratios found in the EC-SCZ group using ANOVA and pairwise comparisons.

4. Discussion

In this focused cross-sectional investigation we tested the specific hypothesis that subcortical volumes may differ in schizophrenia as a function of illness stage. Examination of subcortical gray matter volumes revealed differences in amygdala volume across different illness stages. Bilateral mean volumetric ratios of the amygdala were smaller in the EC-SCZ, as compared to the healthy-control (HCS) and the high-risk (HR) groups. This finding possibly reflects the specificity in amygdala volume changes, as lower total cerebral volumes have been noted in patients with schizophrenia (Wright et al., 2000). Unlike some previous studies, however, significant group differences in thalamic, nucleus accumbens, putamen, GP or hippocampal raw volumes or volumetric ratios were not found in the present samples (Rimol et al., 2010; Watson et al., 2012a). Group differences in age, amount of education or medication treatment did not account for the group differences in amygdala volume. However, duration of illness was inversely correlated with amygdala volume. Collectively, these effects suggest that early illness course may be particularly associated with loss of volume in subcortical structures mediating the stress response.

4.1. Amygdala volume reductions in early course of illness

The principal finding of decreased amygdala volumes in schizophrenia illness is consistent with previous studies (Niu et al., 2004; Shenton et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2008). However, these results provide a key extension: by examining different phases of illness, present findings demonstrated that patients more proximal to their illness onset (mean illness duration = 4.27 months) had smaller bilateral amygdala mean volumetric ratios than the HCS and HR groups. Previous studies have shown mixed results, with patients in the early phase of illness exhibiting amygdala volumes that are either smaller (Joyal et al., 2003; Watson et al., 2012b; Witthaus et al., 2009), or similar (Bodnar et al., 2010; Vita et al., 2006) to healthy controls and those at high-risk for schizophrenia. Meta-analytic findings are similarly mixed. Meta-analysis of volumetric studies failed to detect volume differences in the amygdala in patients with first-episode schizophrenia, compared to control subjects (Vita et al., 2006). Meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies has shown decreased left amygdala volumes in patients with chronic, compared to first-episode, schizophrenia (Chan et al., 2011), though an earlier meta-analysis demonstrated similarly decreased left amygdala volume in patients with first-episode schizophrenia and chronic schizophrenia (Ellison-Wright et al., 2008). Differing methodologies across studies may account for these differences, as many of these studies examined raw amygdala volume (Bodnar et al., 2010; Joyal et al., 2003; Watson et al., 2012b), or used voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analyses (Chan et al., 2011; Ellison-Wright et al., 2008; Witthaus et al., 2009). A prior volumetric study across illness phases demonstrated bilateral amygdala enlargement among patients with a non-schizophrenic first-episode of psychosis only, compared to healthy subjects, and found no differences in amygdala volume between healthy control subjects and those with first-episode schizophrenia (Velakoulis et al., 2006). Yet, longitudinal examination of the amygdala-hippocampal complex has the suggested acute insult at early stages of illness without differential progression of volume reduction in chronic schizophrenia (Yoshida et al., 2009). Our finding of reduced amygdala volumetric ratios in those with early-course schizophrenia compared to healthy control and high-risk subjects warrants replication with larger sample sizes.

In our study, amygdala volumes were similar between the EC-SCZ and C-SCZ groups, though there was no difference in amygdala volumes between the C-SCZ and HCS groups. Correlation analysis demonstrated a significant positive correlation with amygdala volume and amygdala volumetric ratio and age. Yet, reduced amygdala volume among patients with chronic schizophrenia has been demonstrated in other studies (Bora et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2011; Niu et al., 2004; Shepherd et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2010), though see (Tanskanen et al., 2005). The lack of difference in amygdala volume between C-SCZ and HCS in our study may have occurred for two reasons: i) this finding may have been obscured in our study due to the strict separation of subjects with schizophrenia according to duration of illness, whereas perhaps prior studies included a broader range of patients; and ii) there may be important methodological differences in amygdala extraction, given that the current study employed automated segmentations tools – namely, FreeSurfer (as opposed to manual definitions). Accurate segmentation of the amygdala is challenging, due to its small size, and FreeSurfer remains one of the more accurate methods for automatic segmentation of the amygdala (Morey et al., 2009). Amygdala volumes have been shown to be significantly correlated between FreeSurfer and manual segmentation, with similar sample sizes needed to detect a variety of effect sizes for volume changes between the methods (Morey et al., 2009). Of note, the sample sizes in this study are close to the sample sizes needed to detect large effects in differences in amygdala volume (Morey et al., 2009). Still, differences in other parameters of segmentation may account for differences among studies. FreeSurfer segmentation of additional subcortical regions, including thalamus and hippocampus, has also been shown to be similar to manual segmentation (Keller et al., 2012; Morey et al., 2009).

Amygdala volume has been shown to be negatively correlated with memory in schizophrenia (Killgore et al., 2009). The specificity of decreased amygdala volumes in EC-SCZ may also reflect neurodevelopmental, rather than neurodegenerative, processes marked by specific insults early in disease process and development (Chiapponi et al., 2013). In our study duration of illness was also positively correlated with amygdala raw volume and volumetric ratio, reflecting the smaller volumes found in early schizophrenia. In longitudinal studies, gray matter volumes of the amygdala (and other subcortical regions) show limited differences in the progression of volumetric changes across time between patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls, despite earlier noted volumetric differences (Andreasen et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2008). In addition, the rate of decreases in overall gray matter and white matter volume appears to differ between patients and control subjects, though studies vary on whether patients or control subjects demonstrate faster rates of volume loss (Bose et al., 2009; Hulshoff Pol et al., 2002). However, a recent study measuring free water in diffusion weight images has demonstrated increased extracellular volume in gray matter among patients with first-episode psychosis, suggesting possible neurodegenerative processes such as inflammation (Pasternak et al., 2012). The lack of effects in the HR group suggests that these structural findings may be specific to disease process rather than risk for disease. Of note, we were unable to detect group differences in gray matter volume of other subcortical regions, which have previously been detected in other studies. This discrepancy may stem from methodological differences in region extraction, and analysis (e.g. shape abnormalities as opposed to volume or thickness) (Anticevic et al., 2010; Cobia et al., 2012; Harms et al., 2007).

4.2. Lack of volume differences in other regions

In contrast to a number of studies, this study did not find volumetric differences across illness phase in the hippocampus, nucleus accumbens, putamen, GP and thalamus. Of these, hippocampal and thalamic volume differences in SCZ have been most prominently documented. Overall, reduced hippocampal volumes have been identified in patients with SCZ, as confirmed by meta-analyses (Adriano et al., 2012; Steen et al., 2006). Hippocampal volumes have been shown to be decreased in chronic SCZ (Rimol et al., 2010; Velakoulis et al., 2006), as well as in early course SCZ (Adriano et al., 2012; Velakoulis et al., 2006). Interestingly, these volume changes remain across development, with increased volume reduction with aging in SCZ (Nugent et al., 2007; Pujol et al., 2014). Thalamic volume has also been shown to be reduced in chronic and early course SCZ (Ananth et al., 2002; Crespo-Facorro et al., 2007b; Staal et al., 2001) (though see (Preuss et al., 2005; Womer et al., 2014). This volumetric reduction of the thalamus has been demonstrated with meta-analysis for both chronic and early course SCZ (Ellison-Wright et al., 2008). Despite this evidence, our current study demonstrated no difference in hippocampal or thalamic volumes across any illness phase. Methodological differences in volume extraction or anatomical delineation, or limited sample sizes may account for our null findings. Volume changes of the caudate, putamen, nucleus accumbens, and GP in schizophrenia have been less consistently documented. Caudate nucleus volumes have been shown to be smaller in patients with schizophrenia (Ellison-Wright et al., 2008; Mitelman et al., 2009), though others have shown larger caudate, putamen and GP volumes in patients with schizophrenia (Glahn et al., 2008; Mamah et al., 2007). Nevertheless, other studies found no differences in caudate nucleus, nucleus accumbens and GP volumes in patients with SCZ (Crespo-Facorro et al., 2007a; Wang et al., 2008). Our study also observed no differences in caudate, putamen, nucleus accumbens and GP volumes between a control population and patients with SCZ. Collectively, some of the null effects observed in the current study may reflect reduced power for more subtle differences. These discrepancies notwithstanding, the core effect identified in this study provides a possible novel direction for dynamic structural alterations along the illness course.

4.3. Potential mechanisms underlying disrupted amygdala structure and function

The prodromal phase of schizophrenia may involve aberrant salience processing, with abnormal attention attributed to typically ‘neutral’ external stimuli (Kapur, 2003). The present results showing altered amygdala volumes among patients with EC-SCZ may in part reflect this pathological process, though the exact contribution of the amygdala dysfunction to schizophrenia pathophysiology continues to be examined. The amygdala is known to play an important role in assigning salience to external stimuli (LeDoux, 2000). Moreover, this structure is functionally important for various aspects of emotion processing, including fear conditioning (Phillips and LeDoux, 1992), fear extinction (Herry et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009), and reward processing (Baxter and Murray, 2002). Studies using BOLD functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) also demonstrate disturbances in amygdala functioning in response to emotional stimuli in schizophrenia, consistent with hypotheses of altered emotion processing in this illness (Bleich-Cohen et al., 2009). In addition, fMRI studies of patients with schizophrenia have demonstrated increased BOLD signal activation of the amygdala in response to neutral stimuli, consistent with altered salience processing accounts in schizophrenia (Anticevic et al., 2012a). Some of the functional amygdala abnormalities in schizophrenia may stem from disrupted connectivity with other structures. For instance, analyses of BOLD signal during resting-state show decreased amygdala-prefrontal cortex connectivity among EC-SCZ and C-SCZ compared to HCS (Anticevic et al., 2013b). It remains to be determined in future studies if structural disturbances in the amygdala in part reflect functional alterations with distributed neural systems.

While the present results are statistically robust they cannot reveal causal mechanisms for observed amygdala reductions. Stressful early and adult life events are thought to be major contributing factors to the onset and recurrence of psychosis (Beards et al., 2013; Varese et al., 2012), and animal studies have demonstrated stress-induced alterations of amygdala neuroplasticity, and neuronal size (Hubert et al., 2014; Maroun et al., 2013; Suvrathan et al., 2014; Vyas et al., 2002). It is possible that stress-induced amygdala changes play a role in the timing of the emergence of schizophrenia, but this interpretation remains speculative. The exact mechanisms of reduced amygdala size in schizophrenia remain poorly understood. Post-mortem studies demonstrate a number of molecular and neuronal changes in the amygdala of patients with schizophrenia (Benes and Berretta, 2001; Berretta et al., 2007; Kreczmanski et al., 2007). For instance, decreased total number of neurons in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala has been noted in post-mortem studies of patients with schizophrenia (Kreczmanski et al., 2007; Varea et al., 2012). Changes in mechanisms responsible for inhibitory signaling have been found in the amygdala of patients with schizophrenia, specifically decreases in GAD67 (glutamic-acid-decarboxylase-67), as well as a general marker of synapses, synaptophysin (Benes and Berretta, 2001; Varea et al., 2012). Finally, the expression of specific molecules has been found to be upregulated in the amygdala of patients with schizophrenia, including Apo-D (apolipoprotein-D)(Thomas et al., 2003) and CSPG (chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans) (Pantazopoulos et al., 2010), an important element of the extracellular matrix. Collectively, these post-mortem findings may point to some mechanistic insights regarding the nature of molecular changes that underlie volume reductions.

4.4. Limitations

The cross-sectional, as opposed to longitudinal design, limited some of the interpretations available to this study. We were unable to infer changes in subcortical volumes that might occur as one transitions from a person at-risk for schizophrenia to a person who develops schizophrenia. Similarly, we were unable to inform changes that occur from an early disease to chronic disease state. Of note, results did not reveal a relationship between amygdala volume and symptomology, which may point to a ‘state’ rather than a ‘trait’ effect. Present analyses were also unable to replicate some prior findings showing gray matter volume differences for other regions such as the thalamus and nucleus accumbens, which may, in part, reflect distinct methodological approaches and choice of dependent measures (e.g. shape versus volume). Similarly, we lacked information on total intracranial volume, a measure previously shown to differ between patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls (Gur et al., 1999). In addition, our sample sizes may not have been large enough to detect more subtle differences across some of these structures. Also, the variable accuracy of FreeSurfer (as opposed to strict manual approaches) in delineating subcortical structures may also have contributed to inability to detect size differences in other structures, which are perhaps more subtle. Thus, it will be important to re-examine these questions as the quality of structural imaging and associated processing improves for clinical applications (Glasser et al., 2013). Each subcortical region was also examined as a single, solitary structure, and potential differences among the subregions of each structure (ex: among nuclei of the thalamus or amygdala) could not be explored. Our analysis also used total amygdala volumes as the dependent variable, and comparisons to VBM studies is therefore limited.

4.5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated smaller amygdala volumetric ratios among patients with early-course schizophrenia relative to other groups. While other subcortical structures were examined, no significant group differences in the volumes of the thalamus, nucleus accumbens, putamen, globus pallidus or hippocampus were found. Smaller amygdala volumetric ratios in early-course schizophrenia may reflect neurodevelopmental aspects of the illness, disrupted connectivity, as well as aberrant salience processing characteristic of early illness phases. Finally, smaller amygdala volumes in early-course schizophrenia could arise due to stress-sensitive molecular and synaptic changes associated with the burden of developing the illness, many of which remain to be fully characterized. Future studies examining these findings in a more longitudinal manner, and in direct conjunction with functional task activation may elucidate the role of amygdala volume in schizophrenia pathophysiology.

Highlights.

Results revealed specifically smaller amygdala volumes in early course schizophrenia

Findings did not change when corrected for age, education and medication

Volumes for other subcortical structures were not significantly different across groups

Acknowledgments

Funding sources included the following: National Institutes of Health (DP5OD012109-02 to A.A.); National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2P50AA012870-11 to J.H.K., K01MH086621 to F.W.); National Natural Science Foundation of China (81071099 and 81271499 to Y.T.); National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression to A.A. and F.W.; Fulbright Foundation to A.S. National Institute of Mental Health (5R25MH071584-07 for Y.T.C., PI: Robert Malison).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

J.H.K. consults for several pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies with compensation less than $10 000 per year. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adriano F, Caltagirone C, Spalletta G. Hippocampal volume reduction in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. The Neuroscientist. 2012;18(2):180–200. doi: 10.1177/1073858410395147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananth H, Popescu I, Critchley HD, Good CD, Frackowiak RS, Dolan RJ. Cortical and subcortical gray matter abnormalities in schizophrenia determined through structural magnetic resonance imaging with optimized volumetric voxel-based morphometry. Am J psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1497–1505. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JE, Wible CG, McCarley RW, Jakab M, Kasai K, Shenton ME. An MRI study of temporal lobe abnormalities and negative symptoms in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;58(2–3):123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00372-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Magnotta V, Pierson R, Ziebell S, Ho BC. Progressive brain change in schizophrenia: a prospective longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(7):672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Pressler M, Nopoulos P, Miller D, Ho BC. Antipsychotic dose equivalents and dose-years: a standardized method for comparing exposure to different drugs. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anticevic A, Cole MW, Repovs G, Murray JD, Brumbaugh MS, Winkler AM, Savic A, Krystal JH, Pearlson GD, Glahn DC. Characterizing thalamo-cortical disturbances in schizophrenia and bipolar illness. Cereb Cortex. 2014a;24(12):3116–3130. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anticevic A, Repovs G, Krystal JH, Barch DM. A broken filter: prefrontal functional connectivity abnormalities in schizophrenia during working memory interference. Schizophr Res. 2012a;141(1):8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anticevic A, Repovs G, Van Snellenberg JX, Csernansky JG, Barch DM. Subcortical alignment precision in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1–3):76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anticevic A, Tang Y, Cho YT, Repovs G, Cole MW, Savic A, Wang F, Krystal JH, Xu K. Amygdala connectivity differs among chronic, early course, and individuals at risk for developing schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2014b;40(5):1105–1116. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anticevic A, Van Snellenberg JX, Cohen RE, Repovs G, Dowd EC, Barch DM. Amygdala recruitment in schizophrenia in response to aversive emotional material: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012b;38(3):608–621. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Sheline YI, Csernansky JG, Snyder AZ. Working memory and prefrontal cortex dysfunction: specificity to schizophrenia compared with major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(5):376–384. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01674-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter MG, Murray EA. The amygdala and reward. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(7):563–573. doi: 10.1038/nrn875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beards S, Gayer-Anderson C, Borges S, Dewey ME, Fisher HL, Morgan C. Life events and psychosis: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(4):740–747. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM, Berretta S. GABAergic interneurons: implications for understanding schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(1):1–27. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta S, Pantazopoulos H, Lange N. Neuron numbers and volume of the amygdala in subjects diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(8):884–893. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich-Cohen M, Strous RD, Even R, Rotshtein P, Yovel G, Iancu I, Olmer A, Hendler T. Diminished neural sensitivity to irregular facial expression in first-episode schizophrenia. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30(8):2606–2616. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar M, Malla AK, Czechowska Y, Benoit A, Fathalli F, Joober R, Pruessner M, Pruessner J, Lepage M. Neural markers of remission in first-episode schizophrenia: a volumetric neuroimaging study of the hippocampus and amygdala. Schizophr Res. 2010;122(1–3):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Fornito A, Radua J, Walterfang M, Seal M, Wood SJ, Yucel M, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Neuroanatomical abnormalities in schizophrenia: a multimodal voxelwise meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1–3):46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose SK, Mackinnon T, Mehta MA, Turkheimer FE, Howes OD, Selvaraj S, Kempton MJ, Grasby PM. The effect of ageing on grey and white matter reductions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;112(1–3):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RC, Di X, McAlonan GM, Gong QY. Brain anatomical abnormalities in high-risk individuals, first-episode, and chronic schizophrenia: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of illness progression. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(1):177–188. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiapponi C, Piras F, Fagioli S, Piras F, Caltagirone C, Spalletta G. Age-related brain trajectories in schizophrenia: a systematic review of structural MRI studies. Psychiatry Res. 2013;214(2):83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobia DJ, Smith MJ, Wang L, Csernansky JG. Longitudinal progression of frontal and temporal lobe changes in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;139(1–3):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MW, Anticevic A, Repovs G, Barch DM. Variable global dysconnectivity and individual differences in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Roiz-Santianez R, Pelayo-Teran JM, Gonzalez-Blanch C, Perez-Iglesias R, Gutierrez A, de Lucas EM, Tordesillas D, Vazquez-Barquero JL. Caudate nucleus volume and its clinical and cognitive correlations in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007a;91(1–3):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Roiz-Santianez R, Pelayo-Teran JM, Rodriguez-Sanchez JM, Perez-Iglesias R, Gonzalez-Blanch C, Tordesillas-Gutierrez D, Gonzalez-Mandly A, Diez C, Magnotta VA, Andreasen NC, Vazquez-Barquero JL. Reduced thalamic volume in first-episode non-affective psychosis: correlations with clinical variables, symptomatology and cognitive functioning. NeuroImage. 2007b;35(4):1613–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deserno L, Sterzer P, Wustenberg T, Heinz A, Schlagenhauf F. Reduced prefrontal-parietal effective connectivity and working memory deficits in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2012;32(1):12–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3405-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douaud G, Mackay C, Andersson J, James S, Quested D, Ray MK, Connell J, Roberts N, Crow TJ, Matthews PM, Smith S, James A. Schizophrenia delays and alters maturation of the brain in adolescence. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 9):2437–2448. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd EC, Barch DM. Anhedonia and emotional experience in schizophrenia: neural and behavioral indicators. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):902–911. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison-Wright I, Glahn DC, Laird AR, Thelen SM, Bullmore E. The anatomy of first-episode and chronic schizophrenia: an anatomical likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(8):1015–1023. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, van der Kouwe A, Killiany R, Kennedy D, Klaveness S, Montillo A, Makris N, Rosen B, Dale AM. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33(3):341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, van der Kouwe AJ, Makris N, Segonne F, Quinn BT, Dale AM. Sequence-independent segmentation of magnetic resonance images. NeuroImage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S69–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzeboom HBG, Treiman DJ. Internationally comparable measures of occupational status for the 1988 international standard classification of occupations. Soc Sci Res. 1996;25:201–239. [Google Scholar]

- Gelber EI, Kohler CG, Bilker WB, Gur RC, Brensinger C, Siegel SJ, Gur RE. Symptom and demographic profiles in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2–3):185–194. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn DC, Laird AR, Ellison-Wright I, Thelen SM, Robinson JL, Lancaster JL, Bullmore E, Fox PT. Meta-analysis of gray matter anomalies in schizophrenia: application of anatomic likelihood estimation and network analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(9):774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser MF, Sotiropoulos SN, Wilson JA, Coalson TS. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage. 2013;80:105–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Andreasen NC, Arndt S, Flaum M, Hubbard WC, Ziebell S. The Iowa Longitudinal Study of Recent Onset Psychosis: one-year follow-up of first episode patients. Schizophr Res. 1997;23(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(96)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RE, Turetsky BI, Bilker WB, Gur RC. Reduced gray matter volume in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(10):905–911. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RE, Turetsky BI, Cowell PE, Finkelman C, Maany V, Grossman RI, Arnold SE, Bilker WB, Gur RC. Temporolimbic volume reductions in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(8):769–775. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner H, Maurer K, Loffler W, Fatkenheuer B, an der Heiden W, Riecher-Rossler A, Behrens S, Gattaz WF. Br J Psychiatry. Supplement. 1994. The epidemiology of early schizophrenia. Influence of age and gender on onset and early course; pp. 29–38. 1994/04/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haijma SV, Van Haren N, Cahn W, Koolschijn PC, Hulshoff Pol HE, Kahn RS. Brain volumes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis in over 18 000 subjects. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(5):1129–1138. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms MP, Wang L, Mamah D, Barch DM, Thompson PA, Csernansky JG. Thalamic shape abnormalities in individuals with schizophrenia and their nonpsychotic siblings. J Neurosci. 2007;27(50):13835–13842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2571-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herry C, Trifilieff P, Micheau J, Luthi A, Mons N. Extinction of auditory fear conditioning requires MAPK/ERK activation in the basolateral amygdala. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(1):261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, Magnotta V, Flaum M. Progressive structural brain abnormalities and their relationship to clinical outcome: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study early in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(6):585–594. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert GW, Li C, Rainnie DG, Muly EC. Effects of stress on AMPA receptor distribution and function in the basolateral amygdala. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;219(4):1169–1179. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0557-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Bertens MG, van Haren NE, van der Tweel I, Staal WG, Baare WF, Kahn RS. Volume changes in gray matter in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):244–250. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468(7321):187–193. doi: 10.1038/nature09552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardri R, Pouchet A, Pins D, Thomas P. Cortical activations during auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia: a coordinate-based meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(1):73–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyal CC, Laakso MP, Tiihonen J, Syvalahti E, Vilkman H, Laakso A, Alakare B, Rakkolainen V, Salokangas RK, Hietala J. The amygdala and schizophrenia: a volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study in first-episode, neuroleptic-naive patients. Bio Psychiatry. 2003;54(11):1302–1304. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00597-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):13–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y, Suzuki M, Kherif F, Takahashi T, Zhou SY, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Sumiyoshi T, Seto H, Kurachi M. Multivariate voxel-based morphometry successfully differentiates schizophrenia patients from healthy controls. NeuroImage. 2007;34(1):235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SS, Gerdes JS, Mohammadi S, Kellinghaus C, Kugel H, Deppe K, Ringelstein EB, Evers S, Schwindt W, Deppe M. Volume estimation of the thalamus using freesurfer and stereology: consistency between methods. Neuroinformatics. 2012;10(4):341–350. doi: 10.1007/s12021-012-9147-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WD, Rosso IM, Gruber SA, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Amygdala volume and verbal memory performance in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Cognitive Behav Neurology. 2009;22(1):28–37. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e318192cc67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Kim DJ, Kim TG, Seok JH, Chun JW, Oh MK, Park HJ. Volumetric abnormalities in connectivity-based subregions of the thalamus in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;97(1–3):226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreczmanski P, Heinsen H, Mantua V, Woltersdorf F, Masson T, Ulfig N, Schmidt-Kastner R, Korr H, Steinbusch HW, Hof PR, Schmitz C. Volume, neuron density and total neuron number in five subcortical regions in schizophrenia. Brain. 2007;130(Pt. 3):678–692. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Nair SS, Quirk GJ. A biologically realistic network model of acquisition and extinction of conditioned fear associations in lateral amygdala neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101(3):1629–1646. doi: 10.1152/jn.90765.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Tollefson GD, Charles C, Zipursky R, Sharma T, Kahn RS, Keefe RS, Green AI, Gur RE, McEvoy J, Perkins D, Hamer RM, Gu H, Tohen M, Group HS. Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):361–370. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamah D, Wang L, Barch D, de Erausquin GA, Gado M, Csernansky JG. Structural analysis of the basal ganglia in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;89(1–3):59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mane A, Falcon C, Mateos JJ, Fernandez-Egea E, Horga G, Lomena F, Bargallo N, Prats-Galino A, Bernardo M, Parellada E. Progressive gray matter changes in first episode schizophrenia: a 4-year longitudinal magnetic resonance study using VBM. Schizophr Res. 2009;114(1–3):136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroun M, Ioannides PJ, Bergman KL, Kavushansky A, Holmes A, Wellman CL. Fear extinction deficits following acute stress associate with increased spine density and dendritic retraction in basolateral amygdala neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38(4):2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh L, Suddath RL, Higgins N, Weinberger DR. Medial temporal lobe structures in schizophrenia: relationship of size to duration of illness. Schizophr Res. 1994;11(3):225–238. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda SA, Stevens MC, Folley BS, Calhoun VD, Pearlson GD. Evidence for anomalous network connectivity during working memory encoding in schizophrenia: an ICA based analysis. PloS One. 2009;4(11):e7911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman SA, Canfield EL, Chu KW, Brickman AM, Shihabuddin L, Hazlett EA, Buchsbaum MS. Poor outcome in chronic schizophrenia is associated with progressive loss of volume of the putamen. Schizophrenia research. 2009;113(2–3):241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey RA, Petty CM, Xu Y, Hayes JP, Wagner HR, 2nd, Lewis DV, LaBar KS, Styner M, McCarthy G. A comparison of automated segmentation and manual tracing for quantifying hippocampal and amygdala volumes. NeuroImage. 2009;45(3):855–866. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namiki C, Hirao K, Yamada M, Hanakawa T, Fukuyama H, Hayashi T, Murai T. Impaired facial emotion recognition and reduced amygdalar volume in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2007;156(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narr KL, Bilder RM, Toga AW, Woods RP, Rex DE, Szeszko PR, Robinson D, Sevy S, Gunduz-Bruce H, Wang YP, DeLuca H, Thompson PM. Mapping cortical thickness and gray matter concentration in first episode schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2005a;15(6):708–719. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narr KL, Toga AW, Szeszko P, Thompson PM, Woods RP, Robinson D, Sevy S, Wang Y, Schrock K, Bilder RM. Cortical thinning in cingulate and occipital cortices in first episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2005b;58(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenadic I, Maitra R, Langbein K, Dietzek M, Lorenz C, Smesny S, Reichenbach JR, Sauer H, Gaser C. Brain structure in schizophrenia vs. psychotic bipolar I disorder: a VBM study. Schizophr Res. 2015;165(2–3):212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesvag R, Lawyer G, Varnas K, Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Frigessi A, Jonsson EG, Agartz I. Regional thinning of the cerebral cortex in schizophrenia: effects of diagnosis, age and antipsychotic medication. Schizophr Res. 2008;98(1–3):16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MO, Rostrup E, Wulff S, Bak N, Lublin H, Kapur S, Glenthoj B. Alterations of the brain reward system in antipsychotic naive schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(10):898–905. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu L, Matsui M, Zhou SY, Hagino H, Takahashi T, Yoneyama E, Kawasaki Y, Suzuki M, Seto H, Ono T, Kurachi M. Volume reduction of the amygdala in patients with schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2004;132(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent TF, 3rd, Herman DH, Ordonez A, Greenstein D, Hayashi KM, Lenane M, Clasen L, Jung D, Toga AW, Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, Thompson PM, Gogtay N. Dynamic mapping of hippocampal development in childhood onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;90(1–3):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel-Knochel V, Knochel C, Matura S, Rotarska-Jagiela A, Magerkurth J, Prvulovic D, Haenschel C, Hampel H, Linden DE. Cortical-basal ganglia imbalance in schizophrenia patients and unaffected first-degree relatives. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(2–3):120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okugawa G, Nobuhara K, Takase K, Saito Y, Yoshimura M, Kinoshita T. Olanzapine increases grey and white matter volumes in the caudate nucleus of patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology. 2007;55(1):43–46. doi: 10.1159/000103575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- Pantazopoulos H, Woo TU, Lim MP, Lange N, Berretta S. Extracellular matrix-glial abnormalities in the amygdala and entorhinal cortex of subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):155–166. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Westin CF, Bouix S, Seidman LJ, Goldstein JM, Woo TU, Petryshen TL, Mesholam-Gately RI, McCarley RW, Kikinis R, Shenton ME, Kubicki M. Excessive extracellular volume reveals a neurodegenerative pattern in schizophrenia onset. J Neurosci. 2012;32(48):17365–17372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2904-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106(2):274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Loughead J, Ruparel K, Overton E, Gur RE, Gur RC. Abnormal modulation of amygdala activity in schizophrenia in response to direct- and averted-gaze threat-related facial expressions. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(3):293–301. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss UW, Zetzsche T, Jager M, Groll C, Frodl T, Bottlender R, Leinsinger G, Hegerl U, Hahn K, Moller HJ, Meisenzahl EM. Thalamic volume in first-episode and chronic schizophrenic subjects: a volumetric MRI study. Schizophr Res. 2005;73(1):91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol N, Penades R, Junque C, Dinov I, Fu CH, Catalan R, Ibarretxe-Bilbao N, Bargallo N, Bernardo M, Toga A, Howard RJ, Costafreda SG. Hippocampal abnormalities and age in chronic schizophrenia: morphometric study across the adult lifespan. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(5):369–375. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.140384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rais M, Cahn W, Van Haren N, Schnack H, Caspers E, Hulshoff Pol H, Kahn R. Excessive brain volume loss over time in cannabis-using first-episode schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):490–496. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimol LM, Hartberg CB, Nesvag R, Fennema-Notestine C, Hagler DJ, Jr, Pung CJ, Jennings RG, Haukvik UK, Lange E, Nakstad PH, Melle I, Andreassen OA, Dale AM, Agartz I. Cortical thickness and subcortical volumes in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanfilipo M, Lafargue T, Rusinek H, Arena L, Loneragan C, Lautin A, Feiner D, Rotrosen J, Wolkin A. Volumetric measure of the frontal and temporal lobe regions in schizophrenia: relationship to negative symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(5):471–480. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlagenhauf F, Huys QJ, Deserno L, Rapp MA, Beck A, Heinze HJ, Dolan R, Heinz A. Striatal dysfunction during reversal learning in unmedicated schizophrenia patients. NeuroImage. 2014;89:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segonne F, Dale AM, Busa E, Glessner M, Salat D, Hahn HK, Fischl B. A hybrid approach to the skull stripping problem in MRI. NeuroImage. 2004;22(3):1060–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenton ME, Gerig G, McCarley RW, Székely G, Kikinis R. Amygdala-hippocampal shape differences in schizophrenia: the application of 3D shape models to volumetric MR data. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2002;115(1–2):15–35. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(02)00025-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd AM, Laurens KR, Matheson SL, Carr VJ, Green MJ. Systematic meta-review and quality assessment of the structural brain alterations in schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(4):1342–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staal WG, Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, van Haren NE, Seifert N, Kahn RS. Structural brain abnormalities in chronic schizophrenia at the extremes of the outcome spectrum. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1140–1142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen RG, Mull C, McClure R, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA. Brain volume in first-episode schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:510–518. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.6.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvrathan A, Bennur S, Ghosh S, Tomar A, Anilkumar S, Chattarji S. Stress enhances fear by forming new synapses with greater capacity for long-term potentiation in the amygdala. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences. 2014;369(1633):20130151. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA. Concept of schizophrenia. 9. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2009. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry; p. 1432. Chapter 12.1. [Google Scholar]

- Tan HY, Choo WC, Fones CS, Chee MW. fMRI study of maintenance and manipulation processes within working memory in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1849–1858. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanskanen P, Veijola JM, Piippo UK, Haapea M, Miettunen JA, Pyhtinen J, Bullmore ET, Jones PB, Isohanni MK. Hippocampus and amygdala volumes in schizophrenia and other psychoses in the Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort. Schizophr Res. 2005;75(2–3):283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EA, Dean B, Scarr E, Copolov D, Sutcliffe JG. Differences in neuroanatomical sites of apoD elevation discriminate between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2003;8(2):167–175. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varea E, Guirado R, Gilabert-Juan J, Marti U, Castillo-Gomez E, Blasco-Ibanez JM, Crespo C, Nacher J. Expression of PSA-NCAM and synaptic proteins in the amygdala of psychiatric disorder patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46(2):189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varese F, Barkus E, Bentall RP. Dissociation mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and hallucination-proneness. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(5):1025–1036. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velakoulis D, Wood SJ, Wong MT, McGorry PD, Yung A, Phillips L, Smith D, Brewer W, Proffitt T, Desmond P, Pantelis C. Hippocampal and amygdala volumes according to psychosis stage and diagnosis: a magnetic resonance imaging study of chronic schizophrenia, first-episode psychosis, and ultra-high-risk individuals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):139–149. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vita A, De Peri L, Deste G, Sacchetti E. Progressive loss of cortical gray matter in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of longitudinal MRI studies. Translational Psychiatry. 2012;2:e190. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vita A, De Peri L, Silenzi C, Dieci M. Brain morphology in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging studies. Schizophr Res. 2006;82(1):75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets NL, Hough MG, Douaud G, Matthews PM, James A, Winmill L, Webster P, Smith S. Evidence for abnormalities of cortical development in adolescent-onset schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2008;43(4):665–675. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas A, Mitra R, Shankaranarayana Rao BS, Chattarji S. Chronic stress induces contrasting patterns of dendritic remodeling in hippocampal and amygdaloid neurons. J, Neurosci. 2002;22(15):6810–6818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06810.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Mamah D, Harms MP, Karnik M, Price JL, Gado MH, Thompson PA, Barch DM, Miller MI, Csernansky JG. Progressive deformation of deep brain nuclei and hippocampal-amygdala formation in schizophrenia. Bio Psychiatry. 2008;64(12):1060–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson DR, Anderson JM, Bai F, Barrett SL, McGinnity TM, Mulholland CC, Rushe TM, Cooper SJ. A voxel based morphometry study investigating brain structural changes in first episode psychosis. Behav Brain Res. 2012a;227(1):91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson DR, Bai F, Barrett SL, Turkington A, Rushe TM, Mulholland CC, Cooper SJ. Structural changes in the hippocampus and amygdala at first episode of psychosis. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2012b;6(1):49–60. doi: 10.1007/s11682-011-9141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AL, Chakravarty MM, Lerch JP, Pipitone J, Daskalakis ZJ, Rajji TK, Mulsant BH, Voineskos AN. Disrupted prefrontal interhemispheric structural coupling in schizophrenia related to working memory performance. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(4):914–924. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]