Abstract

A case of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) presenting after surgery for facial trauma associated with multiple facial bone fractures is described. With regard to the oral and maxillofacial region, DIC has been described in the literature following head trauma, infection, and metastatic disease. Until now, only 5 reports have described DIC after surgery for facial injury. DIC secondary to facial injury is thus rare. The patient in this case was young and had no medical history. Preoperative hemorrhage or postoperative septicemia may thus induce DIC.

1. Introduction

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a dynamic pathologic process in which thrombin forms within the vascular system [1]. DIC is commonly associated with malignant neoplasm, major trauma, head injury, infection, and obstetric complications [2]. With regard to the oral and maxillofacial region, DIC has been described in the literature following head trauma, infection, and metastatic disease [3]. However, a review of literature shows only a small number of reports describing DIC in relation to oral and maxillofacial surgery [4]. In particular, few reports have mentioned DIC after surgery for facial injury. We report herein a rare case of DIC after surgery for facial trauma associated with multiple facial bone fractures.

2. Case Presentation

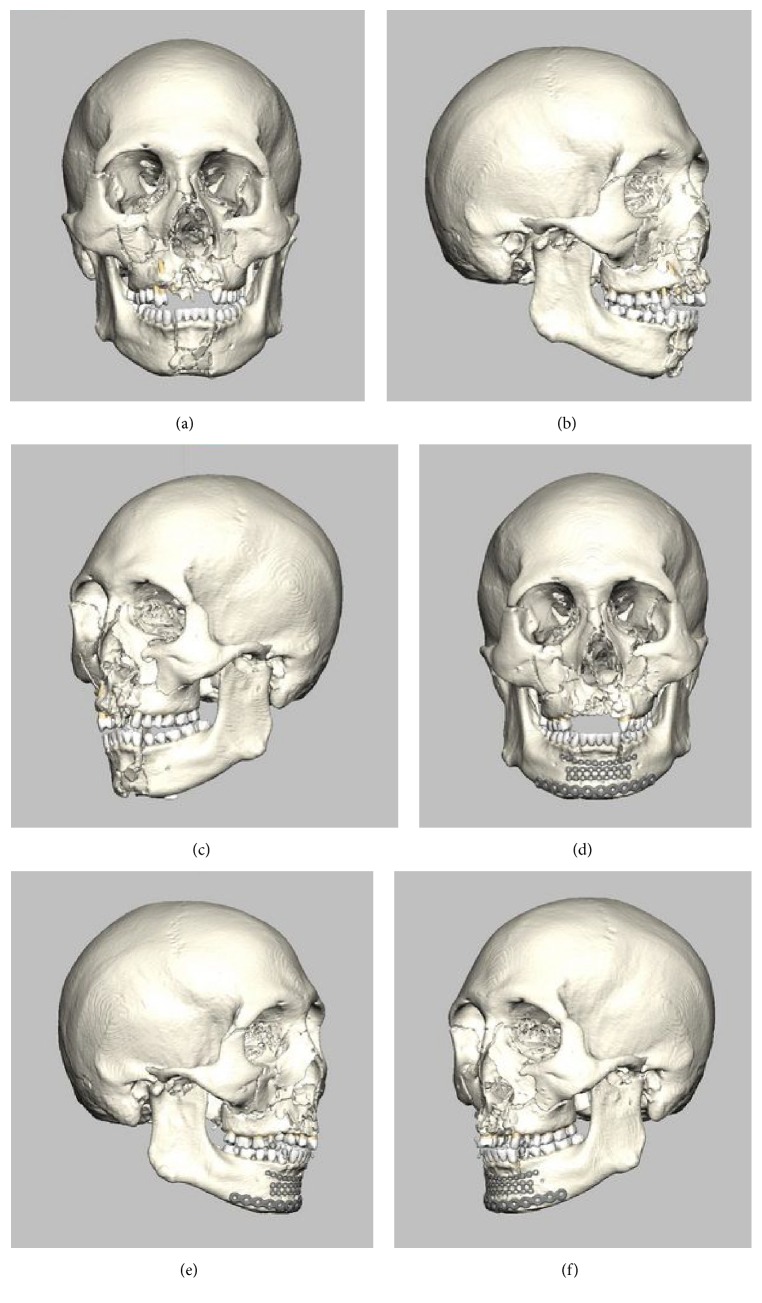

A 21-year-old man was brought to the emergency department at Yamagata University Hospital after becoming involved in a traffic accident while riding a motorbike. On arrival, he was fully conscious and complained of facial pain. Clinical examination showed facial swelling, persistent intraoral and nasal hemorrhage, and bloody otorrhea from the left ear. He showed gross malocclusion associated with discontinuity and mobilization of the maxillary and mandibular dentitions. He had no significant medical history and had been healthy before the accident. Computed tomography (CT) and plain radiography revealed right pulmonary contusion, fractures of a second rib and the right radius, and airway narrowing. In the maxillofacial region, bilateral condylar and mandibular fractures, LeFort II-type fracture, and blow-out fracture of the orbit were recognized (Figure 1). Airway control was achieved by awake orotracheal intubation. Hemostasis was performed by suture compression for oral hemorrhage and by gauze tamponade for nasal hemorrhage under local anesthesia, although nasal hemostasis proved extremely difficult to achieve. Respiratory management with a ventilator was conducted under intravenous sedation until general condition was stable. After another 2 days, the tracheal tube was removed, because no airway narrowing or obstruction was evident. Six days after the accident, tracheotomy and repositioning and fixation of the fractured facial bones, including the mandible, maxilla, zygoma, and blow-out fracture of the orbit, were performed under general anesthesia (Figure 1). Surgery lasted 7 h 16 min, with 30 mL of intraoperative bleeding. Intraoperatively, the patient received blood transfusion of 2 units of red blood cell concentrate due to low hemoglobin levels (7.3 g/dL). The postoperative course was uneventful. On postoperative day 5, however, fever over 39.0°C and shivering were noted. Laboratory examination showed increases in the white blood cell count to 14,060/μL and C-reactive protein (CRP) to 12.1 mg/dL and a decrease in platelets to 131 × 103/μL (down from 238 × 103/μL at the time of the accident). CT revealed no abnormalities other than those at the surgical sites. The next day, the patient showed preshock status with a significant decrease in blood pressure, fever over 39.0°C, and transient loss of consciousness. Emergency laboratory tests showed increases in CRP to 23.9 mg/dL, TBIL to 2.1 mg/dL, creatinine to 0.97 mg/dL, lactate to 4.07 mmol/L, prothrombin time to 21.7 s, FDP (fibrin degradation product) to 10.8 μg/mL, and PT-INR (prothrombin time-international normalized ratio) to 1.86, along with a decrease in platelets to 46 × 103/μL (Table 1). The bacteria was not detected in several tests of blood culture. In the evaluation of respiratory system, PaO2 was 68.2 mmHg, PaCO2 was 28.2 mmHg in blood gas analysis, and PaO2/FiO2 was 341. In circulatory dynamics, noradrenaline was administered sustainably by 0.04ɤ for keeping of blood pressure. In the evaluation of central nervous system, Glasgow Coma Scale was E4V5M6 and a total of 15. Therefore, SOFA (sequential organ failure assessment) score was 9. From the above results, septic shock was diagnosed and the patient was sent to the intensive care unit (ICU). According to the scoring algorithm criteria established by the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) for DIC [21], the patient scored 5. DIC was therefore diagnosed and treatment was initiated. To treat severe infection, cefozopran hydrochloride and freeze-dried polyethylene glycol-treated human normal immunoglobulin were applied by intravenous injection empirically. A total of 38,840 units of thrombomodulin α was administered for the treatment of DIC. After another 7 days, laboratory tests showed a return to nearly normal state, with CRP of 4.09 mg/dL; TBIL of 0.6 mg/dL, Crea of 0.67 mg/dL, WBC of 12,160/μL; platelet count of 175 × 103/μL; prothrombin time of 13.7 s; FDP of 5.3 μg/mL; and PT-INR of 1.17 (Table 1). The patient was then moved to a general ward and the subsequent course was uneventful.

Figure 1.

Images from preoperative and postoperative 3D-CT. (a)–(c) showed that bilateral condylar and mandibular fractures, LeFort II-type fracture, and blow-out fracture of orbit are apparent. (d)–(f) showed that mandibular fracture was fixed by titanium plates and LeFort II-type fracture and blow-out fracture of the orbit were fixed by absorbable plates. (a) Preoperative frontal view. (b) Preoperative lateral view of the right. (c) Preoperative lateral view of the left. (d) Postoperative frontal view. (e) Postoperative lateral view of the right. (f) Postoperative lateral view of the left.

Table 1.

Laboratory data.

| Examination | First visit | Preoperative | POD 5 | POD 6 (preshock) | POD 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (×103/μL) | 17.71 | 10.09 | 14.06 | 10.17 | 12.16 |

| RBC (×106/μL) | 4.69 | 2.33 | 2.91 | 2.7 | 2.55 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.7 | 7.3 | 9.0 | 8.2 | 7.7 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 44 | 22.3 | 26.4 | 25 | 24.1 |

| Platelets (×104/μL) | 23.8 | 9.8 | 13.1 | 4.6 | 17.5 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | <0.10 | 3.82 | 12.10 | 23.9 | 4.09 |

| TBIL (mg/dL) | 0.8 | 0.4 | — | 2.1 | 0.6 |

|

| |||||

| Crea (mg/dL) | 0.94 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.97 | 0.67 |

|

| |||||

| BUN (mg/dL) | 16 | 14 | 20 | 30 | 13 |

|

| |||||

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 4.07 | — | — | 4.07 | — |

|

| |||||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 169 | — | — | 118 | — |

|

| |||||

| PT (s) | — | 11 | — | 21.7 | 13.7 |

| PT (%) | — | 110 | — | 43 | 79 |

| PT-INR | — | 0.94 | — | 1.86 | 1.17 |

| aPTT (s) | — | 27.8 | — | 35 | 30.4 |

| Fbg (mg/dL) | — | — | — | 664 | 624 |

| FDP (μg/mL) | — | — | — | 10.8 | 5.3 |

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | — | — | — | 6.4 | 5.07 |

POD: postoperative day.

3. Discussion

In the oral and maxillofacial region, several reports have described DIC in patients with oral cancer [17], infection [11], injury [3, 13, 16, 17], orthognathic surgery [12], and tooth extraction [5–10, 14, 15, 18, 19]. To the best of our knowledge, however, the English literature contains only 19 reports of DIC in relation to oral and maxillofacial surgery except for oral cancer (Table 2). This means that DIC associated with oral and maxillofacial surgery is uncommon. Of these 19 cases, the most frequent surgery associated with DIC was tooth extraction, in 10 cases. On the other hand, including our case, only 5 cases involved facial injury related to DIC. Table 2 also shows the diseases underlying DIC, with prostatic adenocarcinoma and aortic aneurysm in 4 cases each, and septicemia in 3 cases. Among the 5 cases of facial injury, each patient showed prostatic adenocarcinoma, abruption, septicemia, or no underlying disease. In the remaining cases, Morimoto et al. [17] did not discuss the causative underlying disease. The present patient had no medical history before the traffic accident and preoperative hemostatic function tests yielded normal results. Two reasons could explain DIC in the present case. One is septicemia associated with severe postoperative systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Postoperative stress seemed to not only induce SIRS but also increase its severity. Under severe SIRS, DIC may have developed from hypercoagulability because of abnormally high activity of a chemical mediator [22]. The other is persistent intraoral and nasal hemorrhage after the accident. Laboratory testing showed prominent decreases in hemoglobin (14.7 g/dL to 7.3 g/dL) and platelets (23.8 × 104/μL to 9.8 × 104/μL) between the first visit and the surgery. DIC was possibly triggered in the patient from the large volume of blood loss, consumption of platelets and coagulation factors by acute massive hemorrhage, and a high volume of blood transfusion within a short period [22, 23]. Under such general conditions, the patient had already been in a chronic state of DIC before surgery, and this served to aggravate the symptoms.

Table 2.

DIC relevant to oral and maxillofacial surgery.

| Number | Author | Year | Age | Sex | Surgery | Underlying disease | Progress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Falace and Kelly [5] | 1976 | 85 | M | Extraction of 6 anterior teeth | Occult prostatic adenocarcinoma | Alive |

| 2 | Rawson et al. [6, 7] | 1976 | 45 | F | Extraction of a third molar and submandibular abscess | Septicemia | Dead |

| 3 | Samman [3] | 1984 | 28 | F | Forehead, lip, and tongue laceration from traffic accident | Abruption (38-week pregnancy) | Alive |

| 4 | McKechnie [8] | 1989 | 59 | M | Extraction of maxillary first molar | Occult prostatic adenocarcinoma | Dead |

| 5 | Chishiro [9] | 1989 | 86 | M | Extraction of maxillary molar | Known abdominal aortic aneurysm | Dead |

| 6 | Marshall et al. [10] | 1993 | 24 | F | Extraction of 3 third molars | Unknown | Dead |

| 7 | Currie and Ho [11] | 1993 | 31 | M | Acute dentoalveolar abscess | Septicemia | Dead |

| 8 | Christiansen and Soudah [12] | 1993 | 19 | M | LeFort I osteotomy | None | Alive |

| 9 | McLoughlin et al. [13] | 1994 | 62 | M | Lower lip laceration | Occult prostatic adenocarcinoma, multiple bone metastases | Alive |

| 10 | Herold and Falworth [14] | 1994 | 73 | M | Extraction of upper canine | Occult abdominal aortic aneurysm | Alive |

| 11 | Mehra et al. [4] | 1997 | 65 | M | Scaling, parotitis | Unknown | Alive |

| 12 | Sawaki et al. [15] | 1999 | 62 | M | Extraction of maxillary premolar and molar | Occult prostatic adenocarcinoma, multiple bone metastases | Alive |

| 13 | Cbo et al. [16] | 2001 | 28 | F | Fracture of mandible | None | Alive |

| 14 | Morimoto et al. [17] | 2001 | 37 | F | Infection after tooth extraction | Unknown | Alive |

| 15 | Morimoto et al. [17] | 2001 | 25 | M | Multiple injuries of the mandible | None | Alive |

| 16 | Ita et al. [18] | 2001 | 22 | F | Extraction of mandibular third molar | KTW syndrome | Alive |

| 17 | Peters et al. [19] | 2005 | 82 | M | Extraction of anterior tooth | Aortic aneurysm | Alive |

| 18 | Imai et al. [20] | 2010 | 88 | M | Spontaneous hemorrhage | Aortic aneurysm | Alive |

|

| |||||||

| 19 | Ozaki et al. | 2016 | 21 | M | Multiple facial injury from traffic accident | Septicemia | Alive |

The occurrence of DIC is difficult to predict in cases involving young patients with no underlying disease, as in the present case. Over the last 20 years, no fatal cases of DIC have been reported in association with oral and maxillofacial surgery (Table 2). Therefore, in cases with facial injury, symptoms must be detected and progression of DIC prevented by careful perioperative management.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are competing interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Spero J. A., Lewis J. H., Hasiba U. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Findings in 346 patients. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 1980;43(1):28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wada H., Thachil J., Di Nisio M., et al. Guidance for diagnosis and treatment of disseminated intravascular coagulation from harmonization of the recommendations from three guidelines. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2013;11(4):761–767. doi: 10.1111/jth.12155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samman N. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and facial injury. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1984;22(4):295–300. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(84)90086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehra P., Caiazzo A., Cataudella J. Disseminated intravascular coagulation associated with parotitis: a case report and review. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1997;55(12):1478–1482. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falace D. A., Kelly D. E. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and fibrinolysis as a cause of postextraction hemorrhage. Report of a case. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 1976;41(6):718–725. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rawson D. W., Harrison J. B., Alling C. C., Hamilton M. K. Clinicopathological conference. Case 13, part 1. Journal of Oral Surgery. 1976;34(1):62–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rawson D. W., Harrison J. B., Alling C. C., Hamilton M. K. Clinicopathological conference. Case 13, part 2. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Journal of Oral Surgery. 1976;34(2):173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKechnie J. Prostatic carcinoma presenting as a haemorrhagic diathesis after dental extraction. British Dental Journal. 1989;166(8):295–296. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chishiro T. A case of disseminated intravascular coagulation thought to be caused by tooth extraction in the hypercoagulable condition due to abdominal aortic aneurysm. Nippon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;78(12):1777–1778. doi: 10.2169/naika.78.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall D. A. S., Berry C., Brewer A. Fatal disseminated intravascular coagulation complicating dental extraction. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1993;31(3):178–179. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(93)90120-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Currie W. J. R., Ho V. An unexpected death associated with an acute dentoalveolar abscess—report of a case[a/t] British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1993;31(5):296–298. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(93)90063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christiansen R. L., Soudah H. P. Disseminated intravascular coagulation following orthognathic surgery. The International Journal of Adult Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery. 1993;8(3):217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLoughlin P., Chen S., Phillips J. G. Disseminated intravascular coagulation presenting as perioral haemorrhage. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1994;32(2):94–95. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herold J., Falworth M. A. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy presenting as a bleeding tooth socket. British Dental Journal. 1994;177(1):21–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawaki Y., Yamada M., Kasuya Y., Ueda M. Disseminated intravascular coagulation presenting as hemorrhage after tooth extraction. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1999;57(3):341–344. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(99)90686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cbo Y.-S., Kim K.-W., Yang S.-N. Disseminated intravascular coagulation after a surgery for a mandibular fracture. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2001;59(1):98–102. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.19304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morimoto Y., Ikeuchi M., Yamamoto K., Kirita T., Sugimura M. Clinical study of disseminated intravascular coagulation in oral and maxillofacial regions—predictors of onset and prognosis. Oral Diseases. 2001;7(5):291–295. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2001.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ita M., Okafuji M., Maruoka Y., Shinozaki F. An unusual postextraction hemorrhage associated with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2001;59(2):205–207. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters K. A., Triolo P. T., Jr., Darden D. L. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy: manifestations after a routine dental extraction. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology. 2005;99(4):419–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imai T., Michizawa M., Shimizu H., Yura Y., Doi Y. Spontaneous intraoral hemorrhage as manifestation of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation: case report and review. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2010;68(1):195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gando S., Iba T., Eguchi Y., et al. A multicenter, prospective validation of disseminated intravascular coagulation diagnostic criteria for critically ill patients: comparing current criteria. Critical Care Medicine. 2006;34(3):625–631. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000202209.42491.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handin R. I. Disorders of platelet and vessel wall. In: Issel Bacher K. J., Brauwald E., editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 13th. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill; 1994. pp. 1798–1804. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wada H., Minamikawa K., Wakita Y., et al. Hemostatic study before onset of disseminated intravascular coagulation. American Journal of Hematology. 1993;43(3):190–194. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830430306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]