Abstract

Painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN) is a type of peripheral neuropathic pain that is currently difficult to treat using clinically available analgesics. Recent work suggests a progressive depletion of nitric oxide (NO) in nerve cells may be responsible for the pathobiology of PDN. The nitric oxide donor, 3-methyl-4-furoxancarbaldehyde (PRG150), has been shown to produce dose-dependent analgesia in a rat model of PDN. To gain insight into the mechanism of analgesia, methods to radiolabel PRG150 were developed to assess the in vivo biodistribution in rats. The furoxan ring was labeled with 13N to follow any nitric oxide release and the 3-methyl substituent was labeled with 11C to track the metabolite using PET imaging. The in vitro metabolic stability of PRG150 was assessed in rat liver microsomes and compared to in vivo metabolism of the synthesized radiotracers. PET images revealed a higher uptake of 13N over 11C radioactivity in the spinal cord. The differences in radioactive uptake could indicate that a NO release in the spinal cord and other components of the somatosensory nervous system may be responsible for the analgesic effects of PRG150 seen in the rat model of PDN.

Keywords: Furoxan, nitric oxide (NO), 3-methyl-4-furoxancarbaldehyde (PRG150), positron emission tomography, biodistribution, metabolic stability

Nitric oxide (NO) is a well-known in vivo signaling molecule involved in many physiological and pathological processes.1,2 Biological synthesis occurs endogenously from l-arginine, oxygen, and NADPH by various nitric oxide synthase enzymes.1 The gaseous nature of NO facilitates its free diffusion across cellular membranes, making it ideal for paracrine and autocrine signaling.2 However, due to its existence as a gaseous free radical, NO is highly reactive and its in vivo action is restricted to limited areas. The extravascular half-life of NO is estimated at 0.09 to 2 s depending upon the O2 concentration and the distance between blood vessels.3 Apart from activating the soluble guanylate cyclase and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (sGC/cGMP) signaling pathways, NO also regulates protein function by two chemical reactions: tyrosine nitration4 and S-nitrosation, also known as S-nitrosylation.5 These protein modifications play key roles in maintaining homeostasis in the cardiovascular system,6 learning and memory formation in the central nervous system,1 modulation of skeletal muscle contractions,7 pain and nociception,8 and also play important roles in tumor biology and in inflammation.9,10

Over the past decade, there has been significant research on the development of NO prodrugs to overcome the instability and inconvenient handling of aqueous NO solutions.2 In particular, furoxans, a class of 5-membered heterocycles, have received significant attention as NO donors due to their wide range of NO-related bioactivities including: cytotoxicity,11,12 mutagenicity,13 central muscle relaxant,14 monamine oxidase inhibition,15 and blood pressure lowering activity.16−18 Pseudoaromatic properties help stabilize the ring against acids, electrophiles, and heat.19,20 However, they lack stability toward bases and nucleophiles.19 In furoxans, literature reports suggest that NO release occurs secondary to an attack by a thiolate at the 3- or 4- position leading to ring opening and elimination of nitrosyl anions.21−26

Painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN) is a long-term complication of diabetes that is a type of peripheral neuropathic pain notoriously difficult to treat with clinically available analgesic and adjuvant drugs due to lack of efficacy and/or dose-limiting side-effects.27 Recent work from the Smith laboratory has shown that the furoxan nitric oxide (NO) donor, PRG150 1 (3-methyl-4-furoxancarbaldehyde), produced potent dose-dependent pain relief in a rat model of PDN.27,28 However, information on the metabolic stability and biodistribution of PRG150 is lacking. Hence, the aims of the present study were to assess the in vitro metabolic stability of PRG150 using rat liver microsomes and to utilize PET-CT to assess the biodistribution of PRG150 following administration of single bolus intravenous (IV) and subcutaneous (SC) injection in adult male rats.

In nuclear medicine, positron emission tomography (PET) is a functional imaging technique that can be used to determine concentrations of radioactive tracers in the tissues of living organisms.29 A tracer is composed of a biologically active molecule containing a short-lived radioactive isotope such as oxygen-15 (2 min), nitrogen-13 (10 min), carbon-11 (20 min), or fluorine-18 (110 min).30 Using PET technology, biologic pathways can be traced to receptor sites of drug action. Combining a CT scan with a PET scan permits the images to be coregistered, which allows for accurate location of organs or other regions of interest (ROI). The mean activity in the ROI can be normalized using body weight and radioactivity injected to give standardized-uptake-values (SUV = ROI/(radioactivity injected × body weight)). The normalized data in the form of SUVs provides a more accurate comparison between separate imaging experiments. Furthermore, drug metabolites can be easily located by their radioactivity. In general, radiolabeling and subsequent in vivo PET imaging provides a sophisticated noninvasive way to analyze drug action. However, the analysis of nitric oxide releasing furoxans, such as PRG150, presents a unique challenge because if NO release is to be monitored by PET imaging, nitrogen-13 must be used, despite its short half-life (10 min). When working with 13N, procedures and purification must be rapid to obtain an adequate dose.31 Fortunately, carbon metabolites can be imaged with longer-lived carbon-11 isotopes. Herein, we report a facile method for labeling and purifying 13N and 11C labeled 3-methyl-4-furoxancarbaldehyde.

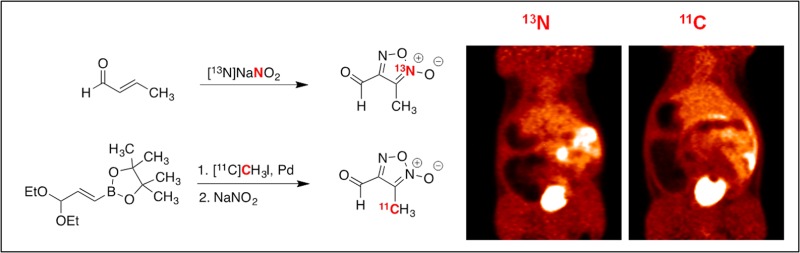

Fruttero et al. described the original synthesis of 3-methyl-4-furoxancarbaldehyde in 1989 and demonstrated by 1H NMR spectroscopy that the aldehyde was quantitatively hydrated in water.32 The furoxan molecule was synthesized by reacting crotonaldehyde with nitrous acid. Due to the simplicity of this reaction, we thought a 13N-radiolabeled version could be feasible if 13NO2– could be produced. Unfortunately, there is no cyclotron target that produces solely 13NO2–. Typically 13NH4+ is produced by bombarding water containing ethanol as a reductant to quench oxidation.31 However, if the ethanol is omitted, radio yield favors 13NO3– with 1% 13NO2–. Unfortunately, 13NO3– could not be used to make furoxans and so it must be reduced to 13NO2– prior to radiotracer synthesis.

Quantitative reduction of 13NO3– to 13NO2– can be achieved using a copperized cadmium reduction column.33−35 Once the crude cyclotron product is passed through a reduction column and subsequently a basic alumina Sep-Pak, 13NO2– is trapped on a small quaternary methylammonium (QMA) anion exchange cartridge. Concentrated saline (23.4% w/v; 0.15 mL) effectively eluted 90% of the radioactivity. With 13NO2– in hand, the furoxan was made by heating 13NO2– with crotonaldehyde, acetic acid, and sodium nitrite at 70 °C for 7 min. This method was also applied to other alkyl α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (Table 1).

Table 1. Radiosynthesis of 3-Alkyl-4-furoxancarbaldehydes.

| compd | R | radiochemical yielda (%) | radio puritya (%) | specific activitya (Ci/mmol) | doseb (mCi) | nc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [13N] 1 | methyl | 34 ± 2 | >99 | 0.3 | 23 ± 1 | 3 |

| [13N] 2 | ethyl | 14 ± 2 | 94 ± 3 | 0.5 | 11 ± 2 | 3 |

| [13N] 3 | propyl | 13 ± 6 | 94 ± 3 | 0.5 | 8 ± 4 | 3 |

| [13N] 4 | isopropyl | 11 ± 1 | 91 ± 2 | 1.3 | 8 ± 2 | 3 |

| [11C] 5 | methyl | 21 ± 8 | 88 ± 3 | 220 | 25 ± 12 | 3 |

Assessed by HPLC after radiosynthesis and Sep Pak purification (decay corrected).

Activity in the dose (3 mL) after synthesis (typical synthesis time: 13N 20 min, 11C, 60 min).

n is the number of repetitions.

In general, there was a decrease in radiochemical yield with increasing alkyl chain length, which is likely due to poor solubility under aqueous conditions. Attempts were made using preparative HPLC to purify 13N radiotracers, but a dose adequate for PET imaging could not be produced. Due to time constraints when working with 13N isotopes, purification was optimized experimentally by pressure transferring the crude reaction mixture through several Sep-Paks in series to produce a radiotracer of high radio and chemical purity (see Supporting Information).

After having optimized the purification procedure, it was hypothesized that a 11C-labeling procedure could be designed and that the same Sep-Pak purification technique could be utilized, provided that similar conditions could be maintained. We envisioned making a 11C-protected crotonaldehyde species 7 by using a Suzuki cross coupling reaction with pinacolboron precursor366 and 11C methyl iodide followed by furoxan ring formation using nitrous acid (Table 1). The necessary 11C intermediate was made by bubbling methyl iodide into a THF solution containing the precursor, palladium, ligand, and sodium acetate followed by heating for 10 min at 70 °C, which was adequate for the in situ conversion to 11C diethoxy crotonaldehyde 7. After cooling, acetic acid was added, followed by sat. NaNO2. The reaction mixture was returned to the heating block for an additional 10 min. After cooling and diluting with water (deionized, 0.5 mL), the crude reaction mixture was pressure-transferred through the same Sep-Pak train used to purify the 13N-derivative, using water (deionized, 3.25 mL) as eluent.

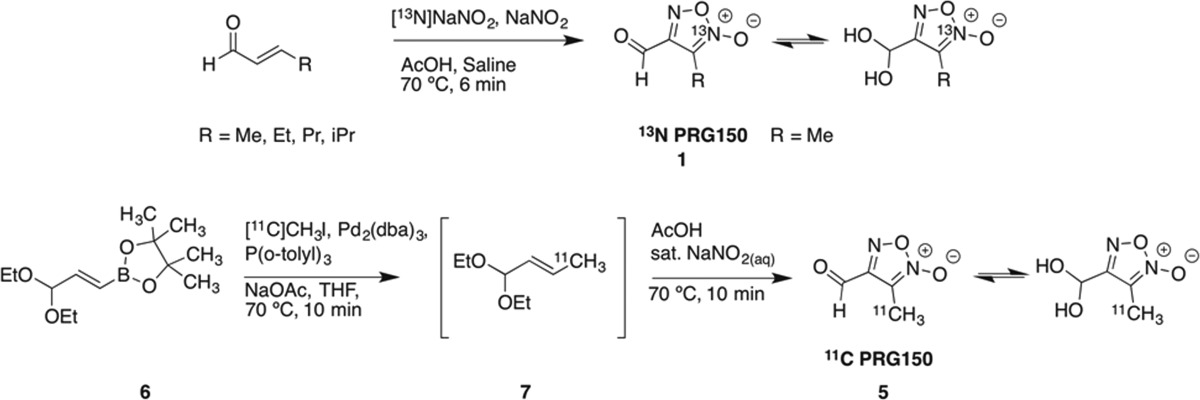

The synthesized 13N and 11C tracers were imaged in adult Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 2). Due to the short half-life of the radiotracers and unique molecule metabolism, it was essential for the animals to be anesthetized (isoflurane) and in the PET scanner prior to tracer administration. Tracers were injected intravenously through a tail vein catheter and dynamically imaged for 60 min. 13N PRG150 time-SUV plots show major distribution in the cardiovascular system followed by the liver, kidneys, and bladder. 11C PRG150 images also show major uptake into the liver, kidneys, and bladder. In both cases, the 13N and 11C PRG150 radioactivity peaked in the liver at 1.5 min (Figure 1). In the kidneys, however, 13N radioactivity peaked at 2.5 min, while the 11C PRG150 peaked at 5.5 min. The discrepancy suggests that IV administered PRG150 is releasing NO almost immediately upon injection and that it is cleared quickly. The 11C metabolite appears to remain in the systemic circulation until the kidneys filter it out shortly after the 13N metabolites. A comparison of the radioactivity elimination in the spinal cord revealed a higher peak uptake of 13N at 5.5 min, compared to 11C in both IV (6.5 min) and SC (17.5 min) administration (Figures 1 and 2). In addition, 13N radioactivity from PRG150 remained in the spinal cord outside of the 60 min PET scan window, while 11C radioactivity was depleted after 45 min. The differences in radioactive uptake could indicate NO release at multiple levels of the somatosensory nervous system including the dorsal root ganglia and the spinal cord thereby contributing to the analgesic effects of PRG150 in the rat model of PDN8,37−39 by addressing the underlying depletion of NO bioactivity in this neuropathic pain condition.26

Figure 1.

PET mean TACs (time-activity curves) of PRG150 in the spinal cord (left) and liver (right) (n = 2).

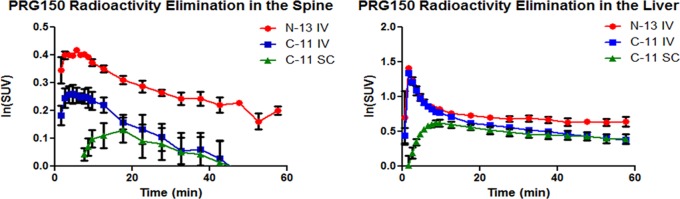

Figure 2.

Rat PET images: (A) 13N PRG150 in the spinal cord (left), coregistered (middle), and CT template (right). (B) Summed images 0–60 min post-tracer injection, 13N PRG150 IV (left) and 11C PRG150 IV (right).

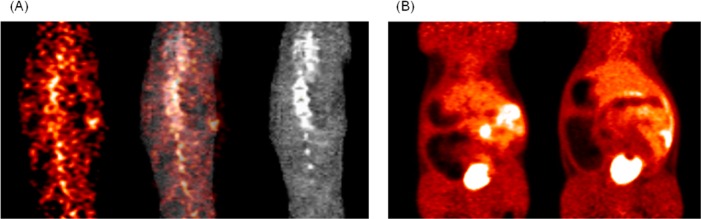

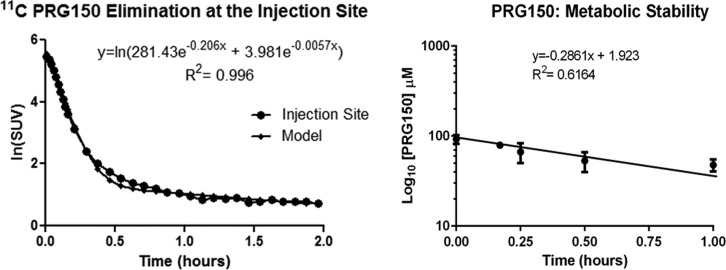

The analgesic efficacy of PRG150 was assessed in the widely utilized streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat model of PDN following single bolus subcutaneous injection (SC) into the back of the neck. The time of onset of analgesia was 15 min, peak analgesia occurred after 60 min, and the duration of pain relief was ∼3 h after single SC bolus dose administration.27 To gain insight into the extended period of pain relief produced by single SC bolus doses of PRG150 in a rat model of PDN,2711C PRG150 was administered similarly, into the back of the neck of one adult male Sprague–Dawley rat. Using the radioactivity amount injected and animal weight to normalize PET-CT data to SUVs, the subcutaneous injection site ROI data was plotted and fitted with a biexponential trend line to estimate rates of distribution and elimination with SC administration (Figure 3); the in vivo half-lives (t1/2) of SC 11C PRG150 were found to be 3 min in the distribution phase and 120 min in the elimination phase. The peak radioactive uptake in the spinal cord (17.5 min) correlates well to the onset of analgesia (15 min) seen in the rat model of PDN.27 Also, there was a 37 min difference of peak radioactivity uptake in the kidneys when comparing IV (5.5 min) to SC administration (42.5 min) of 11C PRG150. Slow elimination from the injection site and delayed kidney uptake could explain the longer duration of analgesia seen when PRG150 is administered subcutaneously.

Figure 3.

PET TAC (time-activity curve) of the subcutaneous injection site fitted with a biexponential model (left). The in vitro metabolic stability of PRG150 in rat liver microsomes (right).

For an in vitro comparison, the metabolic stability of PRG150 was assessed using rat liver microsomes. Specifically, rat liver microsomes (protein concentration, 1.2 mg/mL) were incubated with excess PRG150 (100 μM) at 37 °C in the presence of NADPH (1 mM). The percentage of PRG150 remaining in the microsomal incubates at each time of assessment was calculated by comparing the concentration of PRG150 remaining in the incubate at each sampling time, relative to the concentration at each sampling time, relative to the concentration at the start of incubation (0 min) that was arbitrarily assigned a value of 100%. It is important to note that in the control experiments ran in parallel, the concentration of PRG150 did not decrease when NADPH was omitted. The in vitro half-life (t1/2) of PRG150 in rat liver microsomes was 2.4 h and the intrinsic clearance (CLint) was 5.73 μL/min·mg protein (Figure 3). These in vitro parameter values are in the acceptable range for a novel compound with potential for human use as a novel analgesic to treat PDN.

In summary, to help elucidate the mechanism of analgesia seen in rat models of PDN with PRG150, methods were developed to label the furoxan moiety in two different positions to determine biodistribution in rats. Using 13NO2–, PRG150 and other 3-alkyl-furoxancarbaldehydes were labeled using nitrous acid to follow nitric oxide release with PET imaging. For a comparison, a method to synthesize 11C PRG150 was developed to track the carbon metabolite. A Suzuki cross coupling of the boronate precursor 6 with 11C methyl iodide furnished 11C diethoxy crotonaldehyde 7in situ. Using nitrous acid, 11C PRG150 could be made in moderate radiochemical yield (13N PRG150 34% and 11C PRG150 21%) and good specific activity (13N PRG150 0.3 Ci/mmol and 11C PRG150 220 Ci/mmol). In addition, the 13N and 11C tracers could be purified quickly using only Sep-Paks and were subsequently administered to rats. Data from the PET-CT scans show an increase of 13N radioactivity in the spinal cord compared to 11C activity, indicating a possible site of action for the analgesic effects of PRG150. Both tracers behave similarly in the heart, liver, kidneys, and bladder. The in vivo and in vitro data suggests PRG150 could potentially be a novel analgesic that could effectively treat painful diabetic neuropathy, a type of neuropathic pain that is difficult to treat.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ronald J. Crowe, Karen B. Dolph, and Michael S. Waldrep for assistance with radioisotope production and Margie Jones and Jaekeun Park for assistance with PET-CT animal imaging experiments.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- PDN

painful diabetic neuropathy

- NO

nitric oxide

- PRG150

3-methyl-4-furoxancarbaldehyde

- PET

positron emission tomography

- μPET

micropositron emission tomography

- CT

computed tomography

- Pd2(dba)3

tris(dibenzylideneacetone) dipalladium (0)

- ROI

region of interest

- SC

subcutaneous

- IV

intravenous

- SUV

standard uptake value

- QMA

quaternary methylammonium

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00410.

Full experimental details are available for the synthesis of all compounds, radiosyntheses, HPLC purity tests, in vitro methods, animal studies, and PET images (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ These authors contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

This research was financially supported by a Queensland Emory Development (QED) grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000454. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research also utilized infrastructure purchased with funds from the Queensland Government’s Smart State Research Facilities Fund as well as funds from the Australian Government’s Super Science Translating Health Discovery Initiative from Therapeutic Innovation Australia (TIA) Ltd.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): M.T.S. is named inventor on the PRG150 technology that has been licensed to QUE Oncology, a spin-off company formed by UQ and Emory University, for commercialization. M.T.S. undertakes contract R&D studies at UQ for multiple biopharmaceutical companies.

Supplementary Material

References

- Esplugues J. V. NO as a Signaling Molecule in the Nervous System. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 135, 1079–1095. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y. C.; Janczuk A.; Wang P. G. Current Trends in the Development of Nitric Oxide Donors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 1999, 5, 417–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D. D.; Liu X.; Kantrow S. P.; Lancaster J. R. The Biological Lifetime of Nitric Oxide: Implications for the Perivascular Dynamics of NO and O2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98, 355–360. 10.1073/pnas.98.1.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ischiropoulos H. Biological Tyrosine Nitration: A Pathophysiological Function of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 356, 1–11. 10.1006/abbi.1998.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gödecke A.; Schrader J.; Reinartz M. Nitric Oxide-Mediated Protein Modification in Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathology. Proteomics: Clin. Appl. 2008, 2, 811–822. 10.1002/prca.200780079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R. C.; Loscalzo J. Vascular Nitric Oxide: Formation and Function. J. Blood Med. 2010, 147–162. 10.2147/JBM.S7000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamler J. S.; Meissner G. Physiology of Nitric Oxide in Skeletal Muscle. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 209–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cury Y.; Picolo G.; Gutierrez V. P.; Ferreira S. H. Pain and Analgesia: The Dual Effect of Nitric Oxide in the Nociceptive System. Nitric Oxide 2011, 25, 243–254. 10.1016/j.niox.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst D.; Robson T. Targeting Nitric Oxide for Cancer Therapy. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007, 59, 3–13. 10.1211/jpp.59.1.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J. L. Nitric Oxide as a Regulator of Inflammatory Processes. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2005, 100, 5–9. 10.1590/S0074-02762005000900002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiani M.; Cerecetto H.; González M.; Risso M.; Olea-Azar C.; Piro O. E.; Castellano E. E.; López de Ceráin A.; Ezpeleta O.; Monge-Vega A. 1,2,5-Oxadiazole N-Oxide Derivatives as Potential Anti-Cancer Agents: Synthesis and Biological Evaluation. Part IV. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 36, 771–782. 10.1016/S0223-5234(01)01265-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerecetto H.; González M. Benzofuroxan and Furoxan. Chemistry and Biology. Top. Heterocycl. Chem. 2007, 10, 265–308. 10.1007/7081_2007_064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balbo S.; Lazzarato L.; Di stilo A.; Fruttero R.; Lombaert N.; Kirsch-Volders M. Studies of the Potential Genotoxic Effects of Furoxans: the Case of CAS 1609 and of the Water-Soluble Analogue of CHF 2363. Toxicol. Lett. 2008, 178, 44–51. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertinaria M.; Stilo A. D.; Tosco P.; Sorba G.; Poli E.; Pozzoli C.; Coruzzi G.; Fruttero R.; Gasco A. [3-(1H-Imidazol-4-Yl)Propyl]Guanidines Containing Furoxan Moieties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 1197–1205. 10.1016/S0968-0896(02)00651-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severina I. S.; Axenova L. N.; Veselovsky A. V.; Pyatakova N. V.; Buneeva O. A.; Ivanov A. S.; Medvedev A. E. Nonselective Inhibition of Monoamine Oxidases A and B by Activators of Soluble Guanylate Cyclase. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2003, 68, 1048–1054. 10.1023/A:1026029000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasco A.; Fruttero R.; Sorba G.; Di Stilo A.; Calvino R. NO Donors: Focus on Furoxan Derivatives. Pure Appl. Chem. 2004, 76, 973–981. 10.1351/pac200476050973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre G.; Boiani M.; Cerecetto H.; Fernández M.; González M.; León E.; Pintos C.; Raymondo S.; Arredondo C.; Pacheco J. P. Furoxan Derivatives as Cytotoxic Agents: Preliminary in vivo Antitumoral Activity Studies. Pharmazie 2006, 61, 54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn H.; Brendel J.; Martorana P. A.; Schönafinger K.; Lombaert N. Cardiovascular Action of the Furoxan CAS 1609, A Novel Nitric Oxide Donor. Br. J. Pharmocol. 1995, 114, 1605–1612. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. A.; Xian M.; Tang X.; Wu X.; Wen Z.; Cai T.; Janczuk A. J. Nitric Oxide Donors: Chemical Activities and Biological Applications. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1091–1134. 10.1021/cr000040l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasinszki T.; Havasi B.; Hajgató B.; Westwood N. P. C. Synthesis, Spectroscopy and Structure of the Parent Furoxan (HCNO) 2. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 170–176. 10.1021/jp810066r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medana C.; Ermondi G.; Fruttero R. Furoxans as Nitric Oxide Donors. 4-Phenyl-3-Furoxancarbonitrile: Thiol-Mediated Nitric Oxide Release and Biological Evaluation. J. Med. Chem. 1994, 37, 4412–4416. 10.1021/jm00051a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferioli R.; Folco G. C.; Ferretti C.; Gasco A. M.; Medana C.; Fruttero R.; Civelli M.; Gasco A. A New Class of Furoxan Derivatives as NO Donors: Mechanism of Action and Biological Activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 114, 816–820. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stilo A.; Cena C.; Gasco A. M.; Gasco A.; Ghigo D. Glutathione Potentiates cGNP Synthesis Induced by the Two Phenylfuroxancarbonitrile Isomers in RFL-6 Cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1996, 6, 2607–2612. 10.1016/0960-894X(96)00479-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sako M.; Oda S.; Ohara S.; Hirota K.; Maki Y. Facile Synthesis and NO-Generating Property of 4H-[1,2,5]Oxadiazolo[3,4-D]Pyrimidine-5,7-Dione 1-Oxides. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 6947–6951. 10.1021/jo980732y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirode W. F.; Luis J. M.; Wicker J. F.; Wachter N. M. Synthesis and Evaluation of NO-Release From Symmetrically Substituted Furoxans. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 2299–2301. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorba G.; Medana C.; Fruttero R.; Cena C.; Di Stilo A.; Galli U.; Gasco A. Water Soluble Furoxan Derivatives as NO Prodrugs. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 463–469. 10.1021/jm960379t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L. Y.; Tsui D. Y.; Williams C. M.; Wyse B. D.; Smith M. T. The Furoxan Nitric Oxide Donor, PRG150, Evokes Dose-Dependent Analgesia in a Rat Model of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2015, 42, 921–929. 10.1111/1440-1681.12442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. T.Pain-Relieving Compositions and Uses Therefor. Google Patents US 2015/0051404 A1, 2015.

- Ametamey S. M.; Honer M.; Schubiger P. A. Molecular Imaging with PET. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 1501–1516. 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller P. W.; Long N. J.; Vilar R.; Gee A. D. Synthesis of 11C, 18F, 15O, and 13N Radiolabels for Positron Emission Tomography. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8998–9033. 10.1002/anie.200800222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Vallejo V.; Gaja V.; Gona K. B.; Llop J. Nitrogen-13: Historical Review and Future Perspectives. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 2014, 57, 244–254. 10.1002/jlcr.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruttero R.; Ferrarotti B.; Serafino A.; Di Stilo A.; Gasco A. Unsymmetrically Substituted Furoxans. Part 11. Methylfuroxancarbaldehydes. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1989, 26, 1345–1347. 10.1002/jhet.5570260523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thabano J. R. E.; Abong’o D.; Sawula G. M. Determination of Nitrate by Suppressed Ion Chromatography After Copperised-Cadmium Column Reduction. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1045, 153–159. 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llop J.; Gómez-Vallejo V.; Bosque M.; Quincoces G.; Peñuelas I. Synthesis of S-[13N]nitrosoglutathione (13N-GSNO) as a New Potential PET Imaging Agent. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2009, 67, 95–99. 10.1016/j.apradiso.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Vallejo V.; Kato K.; Oliden I.; Calvo J.; Baz Z.; Borrell J. I.; Llop J. Fully Automated Synthesis of 13N-Labeled Nitrosothiols. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 2990–2993. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.03.122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Touré B. B.; Hoveyda H. R.; Tailor J.; Ulaczyk-Lesanko A.; Hall D. G. A Three-component Reaction for Diversity-Oriented Synthesis of Polysubstituted Piperidines: Solution and Solid-Phase Optimization of the First Tandem Aza[4 + 2]/Allyboration. Chem. - Eur. J. 2003, 9, 466–474. 10.1002/chem.200390049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible H.Pain Control; Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara H.; Kaneko K.. Studies on Pediatric Disorders; Springer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud M. A.; Fahmy G. H.; Moftah M. Z.; Sabry I. Distribution of Nitric Oxide-Producing Cells Along Spinal Cord in Urodeles. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 1–7. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.