Abstract

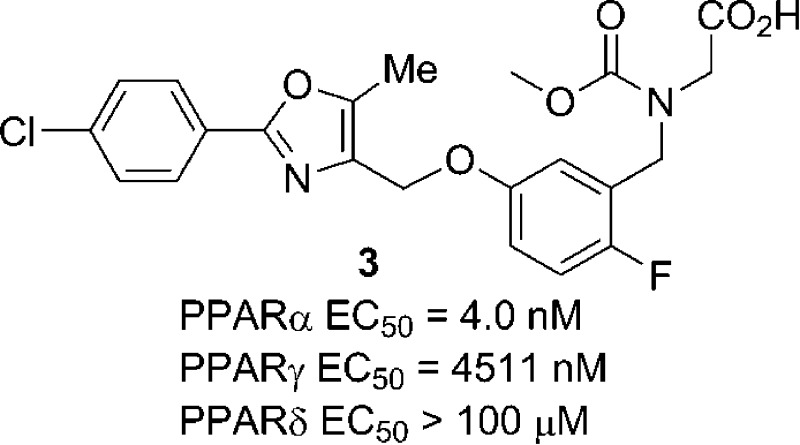

BMS-711939 (3) is a potent and selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α agonist, with an EC50 of 4 nM for human PPARα and >1000-fold selectivity vs human PPARγ (EC50 = 4.5 μM) and PPARδ (EC50 > 100 μM) in PPAR-GAL4 transactivation assays. Compound 3 also demonstrated excellent in vivo efficacy and safety profiles in preclinical studies and thus was chosen for further preclinical evaluation. The synthesis, structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies, and in vivo pharmacology of 3 in preclinical animal models as well as its ADME profile are described.

Keywords: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α selective agonist, high fat fed hamster model, human ApoA1 transgenic mice, pharmacokinetics

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are ligand-activated transcription factors in the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily.1,2 Three subtypes of PPARs, namely, PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARδ, have been identified in various species, including humans. PPARα is highly expressed in the liver and regulates the expression of genes encoding lipid and lipoprotein metabolism.3 Upon binding of PPARα ligand agonists, the resulting conformational change leads to the modulation of a number of PPARα responsive genes, which in turn have pleiotropic effects on plasma lipoprotein levels, atherosclerosis and inflammation. There are currently several synthetic PPARα ligands from the fibrate class of hypolipidemic drugs in clinical use.4,5 Although fibrates are ligands of PPARs, their binding affinity to PPARα is relatively weak.6,7 This results in the relatively high doses (e.g., 200 mg of fenofibrate and 1.2 g of gemfibrozil) needed to achieve clinical efficacy, and unwanted side effects may occur at these high doses. Several potent PPARα selective agonists have been progressed into various phases of clinical development, including GW5907358 and LY518674.9 However, the development of most of these potent and selective PPARα agonist clinical candidates have been suspended. Recently, the PPARα-selective α,γ dual agonist saroglitazar was approved in India for the treatment of diabetic dyslipidemia.10 A potent and efficacious PPARα agonist with an excellent safety profile may provide an opportunity for the treatment of atherosclerosis and dyslipidemia as well as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)11 with minimized side effects. In addition, we considered that a more potent and selective PPARα agonist with minimized disparity in interspecies PPAR activities (particularly human vs rodent) will be useful for mechanism-based safety evaluation in preclinical animal models.

In continuation of our research in the field of PPARs to develop novel therapeutic agents to treat metabolic disorders,12 we have reported the discovery of the selective PPARα agonist 2(13) (Figure 1), which exhibited a high degree of selectivity toward PPARα over PPARγ (PPARα EC50 = 10 nM, EC50 ratio: γ/α = 410), and demonstrated an excellent pharmacological and safety profile in preclinical studies. Inspection of the X-ray crystal structures of 2 bound to the PPARα ligand binding domain (LBD; Figure 2) suggested that the carboxylic acid of 2 forms the well-recognized hydrogen-bonding network with neighboring residues: His440, Tyr464, Tyr314, and Ser280. The 1,3-oxybenzyl central core anchors the acid headgroup and the 4-chlorophenyl oxazole moiety into their appropriate binding pockets. Since the central phenyl core and the benzylic carbon are partially surrounded by hydrophobic residues such as Leu321, Ile317, and Phe318, we envisioned that small hydrophobic substituents on this region may be tolerated and that SAR investigations could be productively conducted within this portion of the molecule to further optimize the binding affinity/potency and/or reduce the human/rodent species difference in PPARα activity. In this paper, we describe the SAR findings from this effort, which resulted in the discovery of 3 (BMS-711939). We also disclose the pharmacokinetic and in vivo efficacy profiling of 3, which progressed into preclinical toxicology studies.

Figure 1.

Fenofibric acid and BMS-687453.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of 2 bound in PPARα LBD with 2.7 Å resolution. Residues within 4.5 Å of benzylglycine are shown with thick sticks. Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines. The PDB deposition number is 3KDT.

The syntheses of 3–6 are described in Scheme 1. Reductive amination of fluoro-substituted hydroxybenzaldehydes 21a–c with glycine methyl ester hydrochloride 22 afforded the secondary amines 23a–c in 85–95% yield. Reaction of 23a–c with methyl chloroformate gave the corresponding methyl carbamates 24a–c in 90–99% yield. Base-mediated alkylation of phenols 24a–c with 4-(chloromethyl)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-5-methyloxazole 25a at 80 °C provided the methyl esters 26a–c in 86–99% yield. Basic hydrolysis of 26a–c provided 3–5 in 90–93% yield. Compound 6 was synthesized in a similar fashion from intermediate 27.14 Compounds 7–13 were synthesized from intermediate 24a and oxazoles 25b–h15 using the same synthetic sequence as described for 3–5.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 3–6.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Et3N, MeOH, NaBH4, 0°C to rt; (b) methyl chloroformate, aq. NaHCO3, THF; (c) 25a, K2CO3, MeCN, 80°C; (d) LiOH, THF-H2O, rt; (e) 1 N aq. HCl.

Compounds 14–20 were synthesized through a slightly different sequence as shown in Scheme 2. Alkylation of 2-fluoro-5-hydroxybenzaldehyde 21a with 4-(chloromethyl)oxazole 25a provided aldehyde 28 in 95% yield. Reductive amination of 28 with 22 afforded the secondary amine 29 in 90% yield. Reaction of 29 with different chloroformates and subsequent hydrolysis of the resulting esters provided compounds 14–20 in 80–93% yield.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 14–20.

Reagents and conditions: (a) K2CO3, MeCN, 80°C; (b) 22, Et3N, MeOH, NaBH4, 0°C to rt; (c) ROCOCl, aq. NaHCO3, THF; (d) LiOH, THF-H2O, rt; (e) 1 N aq. HCl.

Our initial effort to further optimize 2 focused on structural modifications of the central core and the benzylic position of the benzylglycine. The SAR results are shown in Table 1. Introducing a fluorine atom at the 2-position of central core resulted in a very potent and selective PPARα/γ agonist 3 (EC50 γ/α ratio = 1128), with PPARα EC50 = 4 nM and PPARγ EC50 = 4.51 μM in the transactivation assays.13 This compound is ∼2.5-fold more potent than 2 (EC50 = 10 nM) at PPARα and is slightly less potent at PPARγ than 2 (PPARγ EC50 = 4.1 μM). These functional data correspond well to their PPARα and PPARγ binding affinities (Table 1).16 However, the opposite effects were observed when introducing a fluorine atom at the 3-position of central phenyl core; compound 4 (EC50 γ/α ratio =157) is less potent at PPARα (EC50 = 18 nM) and more potent at PPARγ (EC50 = 2.82 μM) than 2. Interestingly, the 4-fluoro-substituted analogue 5 is less active than 2 at both PPARα and PPARγ with a γ/α EC50 ratio of 98. When an (S)-methyl group is placed at the α-position of the benzylglycine of 2, the resulting 6 (EC50 γ/α ratio = 332) has similar potency at PPARα but is more potent at PPARγ than 2. These results indicate that a subtle substitution change on the central phenyl core or at the benzylic position can result in changes in both the PPARα and PPARγ agonist activities and thus the PPARα/γ selectivity. The 2-fluorophenyl glycine analogue 3 has the most potent PPARα agonist activity and is also the most selective PPARα agonist among the three isomeric monofluorinated analogues.

Table 1. Transactivation EC50 and Binding IC50 of 2–6a.

| compd | R | αEC50 (nM) | γEC50 (nM) | γ/α EC50 ratio | αIC50 (nM) | γIC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | H | 10 | 4096 | 410 | 260 | >48000 |

| 3 | 2-F | 4.0 | 4511 | 1128 | 97 | >98400 |

| 4 | 3-F | 18 | 2819 | 157 | 1341 | >15000 |

| 5 | 4-F | 94 | 9168 | 98 | 1563 | >15000 |

| 6 | 8.6 | 2857 | 332 | 671 | >15000 |

Compounds were tested for agonist activity in hPPAR-GAL4 HEK transactivation assays. Transactivation efficacy was defined as percentage of maximum activity as compared with an appropriate standard set at 100% (100 μM fenofibric acid for PPARα, 1.0 μM rosiglitazone for PPARγ). Full PPARα intrinsic activity (>50% relative to 100 μM fenofibric acid) was observed for all tested compounds (n = 1–3).

With lead compound 3 in hand, we systematically investigated the SAR of the “left-hand” phenyl ring substituents and the “right-hand” carbamate substituents, as shown in Table 2. In general, all the 2-fluoro-phenyl central core based compounds show enhanced PPARα agonist activity and PPARα/γ selectivity versus their corresponding unsubstituted phenyl analogues.13 On the “left-hand” phenyl ring (of the oxazole), while the compound without a para substituent (9, PPARα EC50= 59 nM, γ/α ratio =146) is ∼15-fold less potent and far less selective than 3, the para-fluoro compound 8 is only about 3.5-fold less potent than 3 at PPARα and maintains high selectivity (PPARα EC50 = 15 nM, γ/α ratio = 691). Compounds with a nonpolar substituent (7, 10–12) at the para position generally have similar PPARα potencies to 3. However, the relatively bulky polar methylsulfonyl substituent (13) obliterates both PPARα and γ activities. Interestingly, a bulky aliphatic substituent such as t-butyl (12) significantly improved PPARγ potency while maintaining PPARα activity, thus resulting in a significant reduction in PPARα selectivity versus 3. These results suggested that polarity and steric effects play important roles in determining PPARα/γ functional activities and selectivity in this portion of the molecule. This SAR study of the “left-hand” phenyl ring substituents showed that the 4-Cl-phenyl moiety was optimal, providing potent PPARα activity and the highest level of PPARα selectivity.

Table 2. In Vitro Activity of 2-Fluoro Substituted Benzylglycine 3 and 7–20a.

| compd | R1 | R2 | αEC50 (nM) | γEC50 (nM) | γ/α EC50 ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Cl | Me | 4.0 | 4511 | 1128 |

| 7 | Me | Me | 2.8 | 2182 | 787 |

| 8 | F | Me | 14.5 | 10010 | 691 |

| 9 | H | Me | 59 | 8607 | 146 |

| 10 | CF3 | Me | 3.6 | 2062 | 566 |

| 11 | OCF3 | Me | 4.3 | 2384 | 556 |

| 12 | C(CH3)3 | Me | 2.7 | 414 | 154 |

| 13 | SO2Me | Me | >2500 | >25000 | NA |

| 14 | Cl | Et | 4.0 | 4273 | 1085 |

| 15 | Cl | n-Pr | 3.4 | 2013 | 594 |

| 16 | Cl | F(CH2)3 | 10.6 | 4383 | 413 |

| 17 | Cl | n-Bu | 2.8 | 1235 | 435 |

| 18 | Cl | i-Bu | 2.3 | 1504 | 666 |

| 19 | Cl | 4-MePh | 5.6 | 1255 | 224 |

| 20 | Cl | 4-MeOPh | 6.8 | 1087 | 160 |

The corresponding SAR study of the “right-hand” side carbamate showed that simple alkyl carbamates (14–20) generally provide excellent PPARα potency and selectivity (EC50 γ/α ratio > 400-fold), with the ethyl carbamate 14 having almost the same PPARα potency and selectivity (PPARα EC50 = 4 nM, γ/α ratio = 1085) as 3. Interestingly, replacing the terminal methyl group of the n-propyl carbamate 15 with a fluoromethyl (16) resulted in a >2-fold decrease in potency at both PPARα and γ, but retained the high α/γ selectivity. The aryl carbamates (19 and 20) were also potent PPARα agonists, but with slightly lower α/γ selectivity compared to the simple alkyl carbamates. The overall SAR in this carbamate region is similar to that previously observed with 2, with the methyl carbamate being optimal.13

The PPARα potency and selectivity of 3 were further confirmed by testing it in cotransfection assays in HepG2 cells using full length human PPARα and PPARγ receptors.13 In these assays, compound 3 showed excellent PPARα potency (EC50 = 5 nM) with >320-fold selectivity vs PPARγ (EC50 > 1.61 μM). These results correlated well with the data observed from the primary GAL-4 HEK transactivation based screening assays as shown in Table 1. Compound 3 also is a full PPARα agonist in the rodent assays and is >2.5-fold more potent than 2 in rodent PPARα functional assays, with EC50s of 178, 144, and 123 nM for hamster, mouse, and rat, respectively.17 Importantly, compound 3 showed negligible activity (EC50 for transactivation >25 μM and efficacies <15% of standard) against a panel of human nuclear hormone receptors, including PPARδ, LXR, GR, and RXR.

Compound 3 did not show any significant activity in liability profiling assays (e.g., in 5 human CYP isozymes, PXR, and hepatocyte toxicity assays (HHA)).18 No in vitro liabilities were noted in (1) extensive screens for receptor/enzyme binding inhibition; (2) assays for bacterial mutagenicity or CHO cell clastogenicity; and (3) an exploratory Ames test at up to 5000 μg per plate in TA98 and TA100 strains. Cardiovascular safety evaluations were carried out on 3: (1) no hERG and sodium channel activity was observed at concentrations up to 30 and 10 μM, respectively; and (2) no drug-related changes in hemodynamic and electrocardiographic (ECG) effects were observed at up to 20 mg/kg of 3 in a single-dose monkey telemetry study.

Compound 3 also exhibited an excellent pharmacokinetic profile across all tested animal species. Table 3 shows the pharmacokinetic parameters of 3 in mouse, rat, dog, and monkey (cynomulgus). It exhibited low plasma clearance in the mouse, rat, and monkey, and moderate plasma clearance in the dog. The half-life of ranged from 1.8 h in mouse to 26.3 h in monkey. It also had excellent absolute oral bioavailability ranging from 59% (dog) to 100% (rat). Additionally, it has excellent crystalline aqueous solubility (367 μg/mL at pH 7.2).

Table 3. Pharmacokinetic Profile of 3a.

| species | dose route | dose (mg/kg) | tmax (h) | Cmax (μM) | AUCb (μM·h) | CLPl (mL/min/kg) | VSS (L/kg) | t1/2 (h) | F% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mouse | IV | 5 | 13 | 13.8 | 0.6 | 1.8 | |||

| PO | 10 | 0.25 | 22.7 | 17 | 66 | ||||

| rat | IV | 4 | 9.4 | 15.3 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 3.3 | |||

| PO | 8 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 14.9 | 32 | 100 | ||||

| dog | IV | 1 | 3.5 | 10.7 ± 2.4 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 5.5 | |||

| PO | 2 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 59 | ||||

| monkey | IV | 1 | 7.5 | 5.9 ± 2.7 | 3.9 ± 1.5 | 26.3 | |||

| PO | 2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.4 | 8.5 | 65 |

For each experimental study, n ≥ 3.

AUC0–8h reported here, not AUCINF.

Compound 3 has been profiled in multiple animal models of dyslipidemia.19 In a 10-day dose response study in the human ApoA1 transgenic mouse,20 it robustly and dose-dependently increased both ApoA1 and HDL cholesterol, as shown in Table 4. In this study, the reference compound fenofibrate (at a dose of 100 mg/kg) raised serum HDL cholesterol by 88% and lowered triglycerides by 33% after 10 days of dosing. By comparison, compound 3 (at a dose of 50 mg/kg/day) raised HDL cholesterol by 109% and lowered triglycerides by 58%, respectively. These data clearly demonstrated that 3 robustly elevated HDLc and lowered triglycerides in the human ApoA1 transgenic mouse model.

Table 4. Effect of 3 and Fenofibrate on Plasma Parameters in Human ApoA1 Transgenic Micea.

| treatment | serum hu-ApoA1 mg/dL ± SEM (% change) | triglycerides mg/dL ± SEM (% change) | HDLc mg/dL ± SEM (% change) |

|---|---|---|---|

| vehicle | 731 ± 73 | 69.4 ± 6.5 | 192 + 8 |

| fenofibrate, 100 mg/kg/day | 5592 ± 403 (665%*) | 46.9 ± 5.8 (−32.5%*) | 362 ± 23 (88%*) |

| 3, 3 mg/kg/day | 1431 ± 179 (96%*) | 59.6 ± 5.1 (−14.2%) | 223 ± 16 (16%) |

| 10 mg/kg/day | 3656 ± 865 (400%*) | 53.1 ± 3.7 (−23.5%) | 334 ± 19 (74%*) |

| 50 mg/kg/day | 6193 ± 1147 (747%*) | 29.1 ± 4.6 (−58.1%*) | 402 ± 18 (109%*) |

p < 0.05 compared to vehicle-treated group (n = 10). Data represent the mean ± SEM (n = 10).

In a 21-day head-to-head comparison study in a high fat fed hamster model,21 both 2 and 3 dose dependently lowered triglycerides and LDL levels. As shown in Table 5, after 3 weeks of dosing, compound 3 lowered fasting plasma LDLc by 61% at the 3 mg/kg/day dose and 87% at the 10 mg/kg/day dose, respectively; it also reduced plasma triglycerides by 50%, 74%, and 85% at the 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg/day doses, respectively. In comparison, compound 2 lowered fasting plasma LDLc by 46% at the 3 mg/kg/day dose and 60% at the 10 mg/kg/day dose, respectively; it reduced plasma triglycerides by 40%, 45%, and 77% at the 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg/day doses, respectively. For liver triglycerides and cholesterol, compound 3 lowered liver cholesterol by 57% at the 3 mg/kg/day dose and 68% at the 10 mg/kg/day dose, respectively; it also reduced liver triglycerides by 19%, 40%, and 48% at the 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg/day doses, respectively. By comparison, compound 2 only impacted the hepatic lipids at the 10 mg/kg dose level (41% for liver cholesterol and 23% for liver triglycerides). Overall, compound 3 significantly lowered plasma triglycerides and LDLc in a chronic dyslipidemic hamster model and compares favorably to 2 in terms of both potency and overall efficacy in lipid lowering in this model.

Table 5. Effect of Compounds 2 and 3 on Lipid Parameters in High Fat-Fed Hamstersa.

| entry | liver TG mg/dL ± SEM (% change) | liver chol mg/dL ± SEM (% change) | plasma LDLc mg/dL ± SEM (% change) | plasma TG mg/dL ± SEM (% change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| high fat vehicle | 24.1 ± 1.5 | 16.9 ± 1.2 | 91.7 ± 8.1 | 173.5 ± 17 |

| 3, 10 mg/kg | 12.5 ± 1.2 (−48%*) | 5.5 ± 0.5 (−67.5%*) | 12.2 ± 4.6 (−87%*) | 25.2 ± 2.6 (−85%*) |

| 3 mg/kg | 14.5 ± 0.8 (−39.8%*) | 7.3 ± 0.7 (−56.8%*) | 35.7 ± 4.5 (−61%*) | 44.7 ± 4.3 (−74%*) |

| 1 mg/kg | 19.6 ± 0.9 (−18.7%*) | 14.7 ± 1.9 (−13%) | 69.3 ± 11 (−24%) | 85.7 ± 18 (−50%*) |

| 2, 10 mg/kg | 18.5 ± 1.2 (−23%*) | 10.0 ± 1.0 (−40.8%*) | 36.3 ± 5.7 (−60%*) | 39.7 ± 3.6 (−77%*) |

| 3 mg/kg | 19.9 ± 3.0 (−17%) | 14.3 ± 2.4 (−15.4%) | 49.9 ± 8.4 (−46%*) | 95.2 ± 13 (−45%*) |

| 1 mg/kg | 22.6 ± 1.1 (−6%) | 20.7 ± 2.1 (+22%) | 89.3 ± 9.4 | 103.2 ± 11 (−40%*) |

p < 0.05 versus vehicle control. Data represent the mean ± SEM (n = 8).

In summary, the SAR investigation on the oxybenzylglycine-based lead 2 led to the discovery of a series of 2-fluoro-substituted benzylglycine analogues as potent and highly selective PPARα agonists. BMS-711939 (3) was found to be a potent and highly selective PPARα agonist (PPARα EC50 = 4 nM, EC50 γ/α ratio = 1128) that is highly efficacious in elevating HDLc in human ApoA1 transgenic mice and lowering LDLc in dyslipidemic hamsters in chronic efficacy studies. It also robustly lowers triglycerides in both of these animal models. In comparison to 2, BMS-711939 is more potent at PPARα and more selective against PPARγ, and shows superior potency on lowering LDLc and TG in hamsters. On the basis of its potency and selectivity, its excellent in vitro liability profile, favorable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic effects in animal models, compound 3 was selected for further evaluation in preclinical animal toxicity studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeffrey A. Robl for careful proofreading of this manuscript. The Discovery Toxicology department at Bristol-Myers Squibb is acknowledged for the preclinical safety evaluation of BMS-711939.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- LDLc

low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- HDLc

high-density lipoproteincholesterol

- TG

triglycerides

- CYP

cytochromes P450

- hERG

Human Ether-à-go-go-Related Gene

- LXR

liver X receptor

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00033.

Synthetic methods, characterization of key compounds, and biology assay protocols (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pirat C.; Farce A.; Lebègue N.; Renault N.; Furman C.; Millet R.; Yous S.; Speca S.; Berthelot P.; Desreumaux P.; Chavatte P. Targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): development of modulators. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 4027–4061. 10.1021/jm101360s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng P. T. W.; Mukherjee R. PPARs as targets for metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2005, 5, 741–753. 10.2174/1389557054553758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staels B.; Dallongeville J.; Auwerx J.; Schoonjans K.; Leitersdorf E.; Fruchart J.-C. Mechanism of action of fibrates on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Circulation 1998, 98, 2088–2093. 10.1161/01.CIR.98.19.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurav A.; Kaushik M.; Mohiuddin S. M. Fenofibric acid for hyperlipidemia. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2012, 13, 717–722. 10.1517/14656566.2012.658774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd P. A.; Ward A. Gemfibrozil. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in dyslipidaemia. Drugs 1988, 36, 314–339. 10.2165/00003495-198836030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz M.; Mohr P.; Kuhn B.; Maerki H. P.; Hartman P.; Ruf A.; Benz J.; Grether U.; Wright M. B. Comparative molecular profiling of the PPARα/γ activator aleglitazar: PPAR selectivity, activity and interaction with cofactors. ChemMedChem 2012, 7, 1101–1011. 10.1002/cmdc.201100598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman B. M.; Chen J.; Evans R. M. Hypolipidemic drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids are ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α and δ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997, 94, 4312–4317. 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra M. L.; Beneton V.; Boullay A.-B.; Boyer T.; Brewster A. G.; Donche F.; Forest M.-C.; Fouchet M.-H.; Gellibert F. J.; Grillot D. A.; Lambert M. H.; Laroze A.; Grumelec C. L.; Linget J. M.; Montana V. G.; Nguyen V.-L.; Nicodème E.; Patel V.; Penfornis A.; Pineau O.; Pohin D.; Potvain F.; Poulain G.; Ruault C. B.; Saunders M.; Toum J.; Xu H. E.; Xu R. X.; Pianetti P. M. Substituted 2-[(4-aminomethyl)phenoxy]-2-methylpropionic acid PPARα agonists. 1. Discovery of a novel series of potent HDLc raising agents. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 685–695. 10.1021/jm058056x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Mayhugh D.; Saeed A.; Wang X.; Thompson R. C.; Dominianni S. J.; Kauffman R. F.; Singh J.; Bean J. S.; Bensch W. R.; Barr R. J.; Osborne J.; Montrose-Rafizadeh C.; Zink R. W.; Yumibe N. P.; Huang N.; Luffer-Atlas D.; Rungta D.; Maise D. E.; Mantlo N. B. Design and Synthesis of a Potent and Selective Triazolone-Based Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α Agonist. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 5121–5124. 10.1021/jm034173l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosale A.; Saboo B.; Sosale B. Saroglitazar for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia in patients with type 2 diabetes: current evidence. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obes.: Targets Ther. 2015, 8, 189–196. 10.2147/DMSO.S49592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak M.; Lefebvre P.; Staels B. Molecular mechanism of PPARα action and its impact on lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 720–733. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devasthale P. V.; Chen S.; Jeon Y.; Qu F.; Shao C.; Wang W.; Zhang H.; Farrelly D.; Golla R.; Grover G.; Harrity T.; Ma Z.; Moore L.; Ren J.; Seethala R.; Cheng L.; Sleph P.; Sun W.; Tieman A.; Wetterau J. R.; Doweyko A.; Chandrasena G.; Chang S. Y.; Humphreys W. G.; Sasseville V. G.; Biller S. A.; Ryono D. E.; Selan F.; Hariharan N.; Cheng P. T. W. Design and Synthesis of N-[(4-Methoxyphenoxy)carbonyl]-N-[[4-[2-(5-methyl-2-phenyl-4-oxazolyl)ethoxy]phenyl]methyl]glycine [Muraglitazar/BMS-298585], a Novel Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α/γ Dual Agonist with Efficacious Glucose and Lipid-Lowering Activities. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 2248–2250. 10.1021/jm0496436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Kennedy L. J.; Shi Y.; Tao S.; Ye X.-Y.; Chen S. Y.; Wang Y.; Hernández A. S.; Wang W.; Devasthale P. V.; Chen S.; Lai Z.; Zhang H.; Wu S.; Smirk R. A.; Bolton S. A.; Ryono D. E.; Zhang H.; Lim N.-K.; Chen B.-C.; Locke K. T.; O’Malley K. M.; Zhang L.; Srivastava R. A.; Miao B.; Meyers D. S.; Monshizadegan H.; Search D.; Grimm D.; Zhang R.; Harrity T.; Kunselman L. K.; Cap M.; Kadiyala P.; Hosagrahara V.; Zhang L.; Xu C.; Li Y.-X.; Muckelbauer J. K.; Chang C.; An Y.; Krystek S. R.; Blanar M. A.; Zahler R.; Mukherjee R.; Cheng P. T. W.; Tino J. A. Discovery of an Oxybenzylglycine Based Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor α Selective Agonist 2-((3-((2-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-methyloxazol-4-yl)methoxy)benzyl)(methoxycarbonyl)-amino)acetic Acid (BMS-687453). J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2854–2864. 10.1021/jm9016812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X.-Y.; Chen S. Y.; Zhang H.; Locke K. T.; O’Malley K.; Zhang L.; Srivastava R. A.; Miao B.; Meyers D. S.; Monshizadegan H.; Search D.; Grimm D.; Zhang R.; Lippy S. J.; Twamley C.; Muckelbauer J. K.; Chang C.; An Y.; Hosagrahara V.; Zhang L.; Yang T.-J.; Mukherjee R.; Cheng P. T. W.; Tino J. A. Synthesis and structure–activity relationships of 2-aryl-4-oxazolylmethoxybenzylglycines and 2-aryl-4-thiazolylmethoxy benzylglycines as novel, potent PPARα selective activators- PPARα and PPARγ selectivity modulation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 2933–2937. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Yan P.-F.; Zhang G.-L. Preparation of 2-(1-Chloroalkyl)-4,5-dimethyloxazoles and (E)-2-Alkenyl-4,5-dimethyloxazoles. Synthesis 2006, 11, 1763–1766. 10.1055/s-2006-942351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seethala R.; Golla R.; Ma Z.; Zhang H.; O’Malley K.; Lippy J.; Cheng L.; Mookhtiar K.; Farrelly D.; Zhang L.; Hariharan N.; Cheng P. T. W. A rapid, homogeneous, fluorescence polarization binding assay for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma using a fluorescein-tagged dual PPARα/γ activator. Anal. Biochem. 2007, 363, 263–274. 10.1016/j.ab.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compound 2 shows full PPARα agonist activity in rodents with EC50s of 488, 426, and 317 nM for hamster, mouse, and rat, respectively.

- Compound 3 has following profile: Plasma Protein binding, 99.7% (h), 99.8% (m), 99.6% (r), 99% (cyno), 99.5% (d); CYP (inhibition) 3A4, 1A2, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, all IC50s > 40 μM. PXR EC60 > 50 μM; HHA (2C19, 2C9, 2D6, 3A4, TC5) all IC50 > 150 μM; hERG (flux) IC50 > 80 μM; (patch-clamp) 4.0% at 30 μM; Sodium Channel (EP, % block @ 10 μM), 12% @ 1 Hz and 14% @ 4 Hz; Purkinje fiber % change APD90 = −5.4 @ 30 μM.

- Mukherjee R.; Locke K. T.; Miao B.; Meyers D.; Monshizadegan H.; Zhang R.; Search D.; Grimm D.; Flynn M.; O’Malley K. M.; Zhang L.; Li J.; Shi Y.; Kennedy L. J.; Blanar M.; Cheng P. T.; Tino J. A.; Srivastava R. A. Novel Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α Agonists Lower Low-Density Lipoprotein and Triglycerides, Raise High-Density Lipoprotein, and Synergistically Increase Cholesterol Excretion with a Liver X Receptor Agonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 327, 716–726. 10.1124/jpet.108.143271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthou L.; Duverger N.; Emmanuel F.; Langouët S.; Auwerx J.; Guillouzo A.; Fruchart J.-C.; Rubin E.; Denèfle P.; Staels B.; Branellec D. Opposite Regulation of Human Versus Mouse Apolipoprotein A-I by Fibrates in Human Apolipoprotein A-I Transgenic Mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1996, 97, 2408–2416. 10.1172/JCI118687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. R.; Guo Q.; Ippolito M.; Wu M.; Milot D.; Ventre J.; Doebber T.; Wright S. D.; Chao Y.-S. High fat fed hamster, a unique animal model for treatment of diabetic dyslipidemia with peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha selective agonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 427, 285–293. 10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.