Abstract

The mechanism and severity of stroke varies in the setting of malignancy. We report a case of a 68-year-old man with lung adenocarcinoma, who experienced acute neurological symptoms. Imaging studies showed multiple acute ischaemic infarcts in cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres. Further work up was consistent with non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE). We highlight, through a review of the literature, the importance of transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) in defining the above diagnosis. The treatment of NBTE consists of systemic anticoagulation and therapy of the underlying malignancy. Enoxaparin is preferred over warfarin to achieve this goal. He received systemic targeted therapy with erlotinib. A TOE performed 8 months later showed complete resolution of the vegetation.

Background

Malignancies are frequently associated with a hypercoagulable state.1 Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE), or marantic endocarditis, is a paraneoplastic syndrome with an incidence of systemic embolisation of 14–91%.2 3 Histopathologically, aggregates of amorphous sterile fibrin and platelets have been described predominantly on left-sided valves.3 We describe a case of marantic endocarditis with advanced lung malignancy presenting as multifocal cerebral emboli.

Case presentation

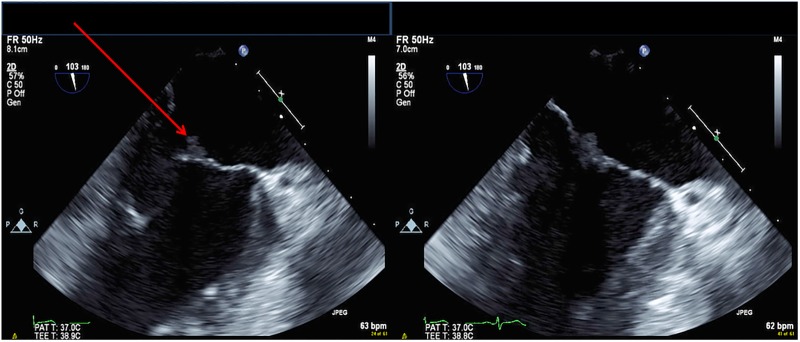

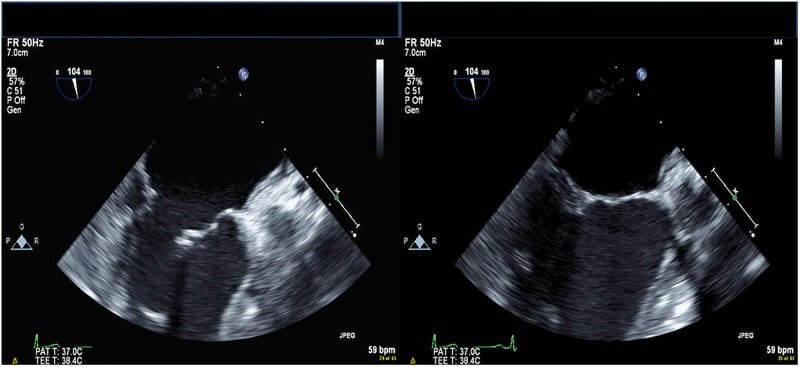

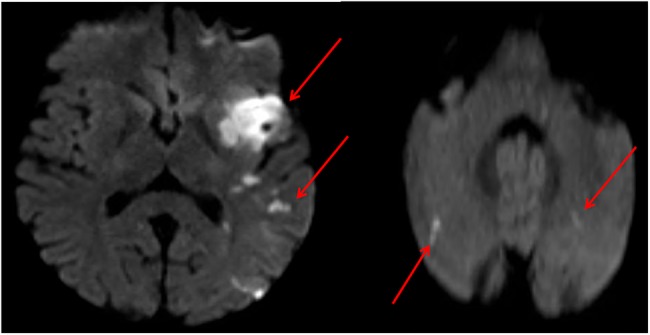

A 68-year-old African-American man, a non-smoker, presented with sudden onset of chest discomfort, confusion and dysarthria. Chest positron emission tomography/CT scans revealed an fluorodeoxyglucose-avid, 4.5×3.3 cm right upper lobe mass (figure 1). Pleural biopsy revealed an adenocarcinoma of the lung with an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 19 deletion mutation (E746 A750). He had an expressive aphasia with a negative carotid artery Doppler, head CT and CT angiogram. An MRI revealed a large acute ischaemic infarct involving the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory, with scattered infarcts in the left temporal and parietal lobes and both occipital and cerebellar lobes (figure 2). Cardiovascular examination revealed neither murmurs nor bruits. There was no arrhythmia on telemetry. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was negative for any source of emboli, but transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) revealed a 6×6 mm mobile echodensity on the anterior mitral valve leaflet, associated with mild mitral regurgitation (figure 3). There were no left ventricular and no atrial thrombi, and neither intracardiac shunting nor aortic pathology on TOE. Three sets of blood cultures were negative and there were no clinical manifestations of infective endocarditis (IE). Routine laboratory tests were unremarkable. The patient underwent inpatient rehabilitation and was discharged on enoxaparin 1.5 mg/kg daily, erlotinib 150 mg daily and physical/speech therapy. A repeat TOE was performed 8 months after continuous targeted therapy and anticoagulation (AC), demonstrating resolution of the initial vegetation (figure 4).

Figure 1.

Chest CT scan showing a 4.5×3.3 cm mass in the apical posterior segment of the right upper lobe.

Figure 2.

Acute ischaemic infarct involving the left middle cerebral artery territory. Multiple smaller infarcts involving the left temporal and parietal lobe, both occipital lobes and both cerebellar hemispheres.

Figure 3.

Transoesophageal echocardiography showing a 6×6 mobile echodensity in the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve, consistent with vegetation.

Figure 4.

Subsequent transoesophageal echocardiography showing resolution of prior vegetation in the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve.

Treatment

The patient was placed on intravenous heparin infusion. When he reached therapeutic range, we bridged him to enoxaparin 1.5 mg/kg daily. Systemic targeted therapy with erlotinib (150 mg daily) was initiated to treat EGFR-mutated adenocarcinoma of the lung.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient did not report any further changes in neurological status. He underwent inpatient rehabilitation for 2 weeks and was discharged to our rehabilitation clinic, where he spent 5 months undergoing physical, speech and occupational therapy.

Discussion

McKay and Wahler proposed the clinical triad of murmur, history of multiple systemic emboli and history of malignancy as one criterion for diagnosing NBTE. Lack of clinical improvement after treatment for IE, negative blood cultures and a history of cerebral embolism of unknown aetiology are other clues for NBTE. Our patient had a lung malignancy with subsequent multiple cerebral emboli, in the absence of a murmur and positive blood cultures, and with a documented valvular lesion on TOE. NBTE is usually seen in advanced stages of cancer, especially mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung as well as ovarian cancer with these two neoplasms accounting for up to 50% of cases.1 3 4

Focal stroke, a diffuse encephalopathic picture or a mixed neurological pattern are the most common neurological manifestations of NBTE.5 These patients are likelier to present with multiple strokes than are patients with IE, who usually have single lesions.4 6 The MCA is the most common location, as was seen in our patient.4 There is an increased incidence of stroke within 3 months of a cancer diagnosis, which progressively rises through the first year (5.1% at 3 months to 8.1% at 1 year).7 Murmurs are often an unreliable sign owing to the small size of marantic vegetations coupled with the fact that 82% of involved valves are structurally undamaged.1 8 We did not see any cutaneous manifestations of NBTE in our patient, but they have been reported.9 Peripheral, renal, mesenteric and coronary embolisation can also occur.1 3 4

Given the high false-negative rate of small vegetations with TTE, it is not unsurprising that our TTE was negative. In a retrospective study of NBTE, vegetations were seen in only 17% of patients screened with TTE.10 Cardiac MRI using Fast Imaging Steady state Precession (TrueFISP) gradient echo or a diffusion-weighted MRI can be pursued with a negative TOE if clinical suspicion remains high.11 Diffusion-weighted MRI also has the potential to distinguish NBTE from IE based on the heterogeneity of the vegetation.11 Treatment of NBTE consists of systemic AC and therapy of the underlying malignancy. Heparin-based AC is preferred as recurrent thromboembolic events are more common with warfarin.1 3 6 8 12 The activation of cytokines (interleukins 1,6), cyclooxygenase-2 genes, type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor, cysteine proteases and tissue factors in malignancy may render the patient less responsive to warfarin.1 3 Given these observations, low-molecular-weight heparin to achieve full AC was administered to our patient.13 Systemic targeted therapy with erlotinib, a reversible tyrosine kinase inhibitor acting on the EGFR, was initiated along with AC and in 8 months the mobile echodensity on the anterior mitral leaflet was no longer seen on TOE. Follow-up CT imaging also showed regression of the lung mass (now 1.6×3.1 cm). It is not possible to surmise the extent to which chemotherapy, AC or the combination contributed to the regression of NBTE in our patient. Chemotherapy,6 14 surgical excision6 15 and radiotherapy6 16 have all been linked to improvement in NBTE. Valvular surgery is typically not necessary in NBTE unless severe valvular dysfunction, decompensated heart failure, recurrent embolic events or contraindications to AC are present.3 8 17 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of NBTE associated with an EGFR-mutated lung cancer.

Our case raises some interesting questions. As the risks of NBTE and subsequent emboli are far greater among mucinous adenocarcinoma, would early AC limit the incidence of NBTE and adverse events in this population? Should TOE be used serially to monitor the vegetation to correlate vegetation size and growth with adverse outcomes? Is lifelong AC warranted following clinical improvement and/or regression of vegetations? Future research is needed to address these and other concerns in NBTE.

Learning points.

The hypercoagulable state of malignancy causes non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE). A high level of clinical suspicion is required to diagnose NBTE, mainly when a patient with a known malignancy develops stroke-like symptoms.

Transoesophageal echocardiography is the most effective diagnostic tool for detection of NBTE.

Treatment of NBTE consists of systemic anticoagulation and therapy of underlying malignancy.

Anticoagulation is paramount to avoid further embolism and permanent neurological disabilities.

Heparin-based anticoagulation is preferred over warfarin, based on observational reports. There are no case-control studies and no clinical trials regarding anticoagulation in this population.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.el-Shami K, Griffiths E, Streiff M. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in cancer patients: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Oncologist 2007;12:518–23. 10.1634/theoncologist.12-5-518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yilmaz KC, Hasirci SH, Bal UA et al. Hypercoagulability in malignancy and a rare case of embolic stroke as a consequence of nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. J Hematol Thrombo Dis 2015;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aryana A, Esterbrooks DJ, Morris PC. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis with recurrent embolic events as manifestation of ovarian neoplasm. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:C12–15. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00614.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee V, Gilbert JD, Byard RW. Marantic endocarditis—A not so benign entity. J Forensic Leg Med 2012; 19:312–15. 10.1016/j.jflm.2012.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers LR, Cho ES, Kempin S et al. Cerebral infarction from non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis: clinical and pathological study including the effects of anticoagulation. Am J Med 1987;83:746–56. 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90908-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong SF, Seow J, Profitis K et al. Marantic endocarditis presenting with multifocal neurological symptoms. Intern Med J 2013;43:211–14. 10.1111/imj.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navi BB, Reiner AS, Kamel H et al. Association between incident cancer and subsequent stroke. Ann Neurol 2015;77:291–300. 10.1002/ana.24325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bathina JD, Daher IN, Plana JC et al. Acute myocardial infarction associated with nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis. Tex Heart Inst J 2010;37:208–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimyai-Asadi A, Usman A, Milani F. Cutaneous manifestations of marantic endocarditis. Int J Dermatol 2000;39:290–2. 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutta T, Karas MG, Segal AZ et al. Yield of transesophageal echocardiography for nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis and other cardiac sources of embolism in cancer patients with cerebral ischemia. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:894–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asopa S, Patel A, Khan OA et al. Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32:696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martín-Martorell P, Insa-Molla A, Chirivella-González MI et al. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis associated with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol 2007;9:744–6. 10.1007/s12094-007-0133-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dearborn JL, Urrutia VC, Zeiler SR. Stroke and cancer—a complicated relationship. J Neurol Transl Neurosci 2014;2:1039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colchero T, López-Sánchez FA, Dominguez-Pérez L et al. [Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis and severe aortic valve regurgitation. Resolution tras chemotherapy]. Med Clin (Barc) 2012;138:271–2. 10.1016/j.medcli.2011.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cockburn M, Swafford J, Mazur W et al. Resolution of nonbacterial endocarditis after surgical resection of a malignant liver tumor. Circulation 2000;102:2671–2. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.21.2671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Zeng J, Xie X et al. Clinical features of systemic cancer patients with acute cerebral infarction and its underlying pathogenesis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:4455–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moustafa S, Patton DJ, Balon Y et al. Mitral valve surgery for marantic endocarditis and multiple cerebral embolization. Heart Lung Circ 2013;22:545–7. 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]