Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer is now often diagnosed in the localized, well-differentiated stage. In the HAROW study, we investigated the care situation with respect to the various treatment options for localized prostate cancer in everyday clinical practice in Germany.

Method

Study physicians for this prospective, multicenter observational study were recruited through the Federation of German Urologists. At six-month intervals, clinical variables were recorded (T category, prostate-specific antigen [PSA], Gleason score, d’Amico risk profile, Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI]) and patients filled out questionnaires (QLQ-C30) regarding their indication-related quality of life (QoL). Covariance analysis was used to adjust for the variable distribution of patient features among the treatment groups.

Results

Data from 2957 patients were available for analysis. The mean follow-up time was 28.4 months overall, and 47.6 months in the active surveillance (AS) group. Younger patients and patients with a CCI of 0 or 1 predominated in the AS and surgery groups; older patients and patients with a CCI of 2 or above predominated in the groups in which palliative treatment strategies such as hormone therapy (HT) and watchful waiting were applied. The HT group had the highest percentage of patients with a Gleason score of 8 or above (21.2%), while the AS group had the highest percentage of patients with a Gleason score of 6 or below (92.5%), as well as the lowest mean PSA value (5.8 ± 3.4 ng/mL) and the highest percentage of patients with a low-risk profile (82.5%). Of 468 patients in the AS group, 170 (36.3%) underwent a change of treatment strategy. After adjustment for the severity of disease, no significant difference with respect to the global quality of life was found between AS and the curative treatment options over the long term.

Conclusion

The study physicians drew a clear distinction between curative and palliative treatment strategies, and the inclusion criteria for AS were largely respected. The observed preference for surgery in low-risk patients indicates overtreatment in this patient group.

Prostate cancer (PCa) ranks third among the causes of cancer death in Germany, where 70 000 new cases occur each year (1). Over the past 20 years, the introduction of screening for PCa and the regular determination of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has led to a stage shift from advanced carcinomas to localized, well-differentiated tumors that frequently have no impact on life expectancy (2, 3). The cancer-specific 15-year survival rate for initially conservatively treated patients over 65 years of age with a Gleason score ≤ 7 is 94.3% (4). Tumors with a Gleason score ≤ 6 do not change their grade of malignancy (5) and display neither metastatic potential nor tumor-specific mortality (6– 8), unless biopsy sampling has missed a portion of the tumor with higher malignancy. According to a systematic review that embraced epidemiological, clinical, and autopsy studies, this results in rates of overdiagnosis and overtreatment ranging from 1.7 to 67% (9).

The current German S3 guideline (10) lists the following treatment options for localized PCa: for intermediate- and high-risk tumors, either prostatectomy (OP) or radiotherapy (RT) in the form of percutaneous irradiation or high-dose-rate (HDR) brachytherapy; for low-risk PCa, additional active surveillance (AS) and low-dose-rate (LDR) brachytherapy. In patients with poor general health or limited life expectancy, palliative strategies are indicated—long-term observation (watchful waiting, WW) and in special cases hormone withdrawal treatment (HT) (Table 1).

Table 1. Treatment strategies for localized prostate cancer according to the German S3 guideline on prostate carcinoma (DGU).

| Strategy | Treatment goal | Treatment type | Treatment | Indication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | Hormone treatment | Palliation | Defensive | Androgen deprivation by surgical or medicinal castration (androgen receptor antagonists, GnRH analogs, GnRH antagonists) |

Life expectancy <10 years |

| A | Active surveillance (AS) | Cure | Defensive, observational |

|

Low risk profile* |

| R | Radiotherapy | Cure | Invasive, definitive |

|

|

|

Low risk profile | ||||

|

Intermediate and high risk profile | ||||

| O | Operation | Cure | Invasive, definitive | Radical prostatectomy (RP)

|

|

| W | Watchful waiting | Palliation | Defensive, observational | Initially no treatment; palliative measures in the event of symptomatic or rapid tumor progression or if requested by the patient | Life expectancy <10 years |

Classification of risk profile according to d’Amico (22): low risk profile: ≤ cT2a and PSA ≤ 10 ng/mL and Gleason score ≤ 6; intermediate risk profile: cT2b or PSA 10–20 ng/mL or Gleason score =7; high risk profile: cT2c or PSA >20ng/mL or Gleason score ≤ 8

*Indication für AS: low risk profile (d’Amico) and tumor in ≤ 2 out of 10–12 biopsy samples obtained according to the guidelines and ≤ 50% tumor infiltration per sample

GnRH, Gonadotropin-releasing hormone; PSA,prostate-specific antigen; LDR, low-dose-rate; HDR, high-dose-rate; DGU, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie (German Urological Society)

It is important to distinguish between the two non-invasive treatment options, AS and WW. AS is a curative strategy. The patient is closely monitored (digital rectal examination, PSA measurement, repeat biopsy), and if any signs of progression are noted, or the patient so wishes, invasive treatment is carried out. In contrast, WW is a palliative strategy with treatment of symptoms as required, usually by means of HT.

Studies comparing the treatment strategies seem to indicate equivalence (11, 12). Prospective randomized trials are problematic in that the low metastatic potential and the lack of cancer-specific mortality make it difficult to reach the patient numbers required for definitive conclusions. A two-armed study had to be discontinued for this reason (13), and a three-armed trial had to be continued with a lower number of cases (14).

Nevertheless, prospective randomized trials of several treatment strategies have recently been initiated. The German PREFERE study compares AS, OP, RT, and brachytherapy (15), while the British ProtecT trial is investigating AS, OP, and RT (14).

When the efficacy of different treatments is practically the same, other factors become much more important, such as treatment-related adverse effects, quality of life (QoL), the feasibility of the treatments in everyday practice, and cost–benefit considerations. Investigation of these aspects is the task of healthcare research (HCR), which examines “[…] the care of individuals and of the population […] under everyday conditions” (16). HCR data can be used to assess the consequences for daily practice of results obtained in the rather artificial setting of randomized studies.

The HAROW study (HT, AS, RT, OP, WW) is the first urological study of the treatment of localized PCa in Germany (17). It describes the various treatment options in detail and examines the evolution of QoL over time. The AS group was observed with particular interest, because when the study began the strategy of AS was relatively unknown and not widely used.

Method

The HAROW study is a multicenter prospective observational study. It was carried out over a 5-year period from July 2008 to July 2013. Of the 259 physicians involved in the study, 86% were urologists in private practice. The criterion for inclusion in HAROW was newly diagnosed cancer confined to the prostate (≤ cT2c) with no evidence of metastasis (N0, M0). Data from 2 957 patients were available for analysis.

Because HAROW was conceived as a non-interventional observational study, no restrictions were placed on the type of treatment or how it was carried out. The decision on how to proceed in each individual case was a matter for the patient and the treating physician.

At the outset of the study AS was a novel strategy with no guideline regulating its application. The indication for AS specified in the study protocol (≤ cT2c, PSA ≤ 10 ng/mL, Gleason score ≤ 6, PSA density ≤ 0.2 ng/mL2, ≤ 2 positive biopsies) reflected the then accepted criteria from the specialist literature (6, 18, 19) and the European PRIAS study (Prostate Cancer Research International Active Surveillance) (20), the largest published prospective study of AS at the time. These indications differ from the criteria now laid down in guidelines (10, 21) with regard to T category (HAROW: all cT2 tumors; guidelines: only ≤ cT2a), PSA density (guideline: not specified), and tumor volume (guideline: maximally 50% in both positive biopsy samples) (Table 1). The patients in the AS group were followed up every 3 months for the first 2 years. Thereafter, they underwent digital rectal examination and measurement of PSA concentration and PSA doubling time (PSA-DT) at 6-monthly intervals. Biopsy was repeated after 1 year and then every 3 years. The criteria for discontinuation of AS were: clinical findings (increased size on digital rectal examination or PSA increase with PSA-DT <3 years), histological evidence of progressive disease (upgrading on repeat biopsy), the patient’s wish, or the treating physician’s recommendation.

Data were acquired at the time of recruitment into the study and then at 6-monthly intervals. The physicians recorded clinical parameters, tumor characteristics (findings in digital rectal examination, PSA concentration, Gleason score, risk profile according to D’Amico [22]), details of treatment, disease course, and comorbidities (with the aid of the Charlson Comorbidity Index, CCI) (23).

The patients gave written answers to questions about communication by their physician, psychosocial care, and health-related QoL. The QoL was established using module C30 of the Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ–C30) of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) (24, 25). This module, developed and validated for use in cancer patients, features a global scale for QoL (rated between 0 and 100) alongside scales for function and symptoms.

A detailed description of the methods can be found in the eBox.

eBox. Description of methods.

The HAROW study was carried out by the Foundation of Men’s Health (Berlin) and financially supported by Gazprom Germania. The study physicians were recruited via the Federation of German Urologists (Berufsverband Deutscher Urologen, BDU). Using the address list of the BDU, potential participants were contacted and invited to a HAROW symposium at the 2007 annual congress of the German Urological Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie), where all interested parties could register to participate. All those who attended the symposium were subsequently contacted again in writing. Thus, the HAROW physicians comprised an arbitrary sample. The goal of recruiting 250 study physicians was achieved. As for case number planning, it was assumed that 1% of the new patients each year would be recruited. At the 2007 rate of 65 000 new cases per annum this was approximately 3000 patients over 5 years.

The study physicians were urged to enrol their patients consecutively in the study. Nevertheless, participation in the study was an individual decision. Arbitrary decisions on study inclusion cannot be ruled out in healthcare research. Patients who did not take part in the HAROW study were treated normally outside the protocol. Any participant who withdrew his consent after observation for less than 6 months (the first observation time point) was excluded from analysis; for those who withdrew consent later, the data up to the last time point before withdrawal were included. Altogether, 3169 patients were recruited and 212 were excluded from analysis owing to early withdrawal or because they could not be assigned to a primary treatment group.

Missing values were recorded as such and factored into analysis accordingly. Furthermore, adjustments of the data set were undertaken: an expert board scrutinized allocation to the treatment groups; based on individual case decisions, implausible entries for change of treatment, progression, disease course, prostate-specific antigen (PSA), PSA doubling time, T category, and Gleason score were altered.

The disease-specific data were evaluated using the statistics software SPSS version 21. The metric variables were assessed in univariate fashion with analysis of variance, the categorical variables with the chi-square test. The probability of error was assumed to be 5%. In the case of multiple tests no Bonferroni correction was carried out.

The data on QoL were analyzed descriptively by treatment group and over the course of up to 3.5 years. Patients who changed treatment were no longer considered. To adjust for the varying distribution of patient characteristics in the different treatment groups, analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were calculated in which global QoL was considered as dependent variable, treatment group as factor, and all patient characteristics listed in Table 2 as covariates. The differences among the treatment groups in the adjusted data were tested for significance by means of the Sidak post-hoc test. In the course of adjustment the missing values reduced the number of cases evaluable for QoL to 2 258.

Results

The mean observation time was 28.4 months. Further questioning of the AS group up to April 2015 extended the mean observation time to 47.6 months.

The characteristics of the patients at the beginning of the study are shown in Table 2. The younger patients and those with the least comorbidities (CCI = 0–1) are concentrated predominantly in the AS and OP groups, while the older patients and those with the most comorbidities (CCI ≤ 2) are mostly in the palliative HT and WW groups. The non-invasively treated groups (AS and WW) are characterized by relatively low PSA concentrations (5.8 ± 3.4 ng/mL and 6.8 ± 4.9 ng/mL) and low proportions of patients with a Gleason score ≥ 8. The AS group contains most (92.5%) of the patients with a Gleason score ≥ 6 and the majority (82.5%) of those with a low risk profile. Among the patients with a low risk profile, 517/1151 (44.9%) underwent surgery, 14.7% were irradiated, and 37.0% were treated non-invasively (AS or WW).

Table 2. Patients’ characteristics at time of study inclusion.

| Total (N = 2957) | HT (n = 204, 6.9%) | AS (n = 468, 15.8%) | RT (n = 486, 16.4%) | OP (n = 1673, 56.6%) | WW (n = 126, 4.3%) | p-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 67.3 | ± 7.5 | 75.3 | ± 6.1 | 67.9 | ± 7.0 | 70.2 | ± 6.6 | 67.8 | ± 6.8 | 72.7 | ± 7.5 | <0.01* |

| Follow-up (months) | 28.4 | ± 16.9 | 30.2 | ± 16.1 | 28.5 | ± 16.4 | 28.5 | ± 16.6 | 28.2 | ± 17.4 | 26.9 | ± 15.6 | 0.45 |

| PSA concentration (ng/mL) | 9.4 | ± 15.0 | 20.4 | ± 41.2 | 5.8 | ± 3.4 | 10.8 | ± 19.2 | 8.8 | ± 7.8 | 6.8 | ± 4.9 | <0.01* |

| Prostate volume (mL) | 39.4 | ± 19.5 | 42.2 | ± 21.4 | 42.8 | ± 20.5 | 37.7 | ± 17.9 | 38.3 | ± 18.5 | 43 | ± 27.8 | <0.01* |

| PSA density (ng/mL) | 0.36 | ± 2.8 | 1.44 | ± 8.99 | 0.15 | ± 0.10 | 0.51 | ± 4.13 | 0.26 | ± 0.27 | 0.21 | ± 0.21 | <0.01* |

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| CCI | <0.01* | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 2031 | (68.7) | 112 | (54.9) | 338 | (72.2) | 279 | (57.4) | 1223 | (73.1) | 79 | (62.7) | |

| 1 | 553 | (18.7) | 45 | (22.1) | 84 | (18.0) | 96 | (19.8) | 302 | (18.1) | 26 | (20.6) | |

| ≤2 | 268 | (9.1) | 45 | (22.1) | 38 | (8.1) | 62 | (12.8) | 106 | (6.3) | 17 | (13.5) | |

| n.d. | 105 | (3.6) | 2 | (0.9) | 8 | (1.7) | 49 | (10.1) | 42 | (2.5) | 4 | (3.2) | |

| T category | <0.01* | ||||||||||||

| T1a/b | 210 | (7.1) | 9 | (4.4) | 99 | (21.2) | 11 | (2.3) | 43 | (2.6) | 48 | (38.1) | |

| T1c | 1619 | (54.8) | 101 | (49.5) | 292 | (62.4) | 242 | (49.8) | 943 | (56.4) | 41 | (32.5) | |

| T2a | 343 | (11.6) | 13 | (6.4) | 56 | (12.0) | 73 | (15.0) | 187 | (11.2) | 14 | (11.1) | |

| T2b | 262 | (8.9) | 25 | (12.3) | 11 | (2.4) | 56 | (11.5) | 161 | (9.6) | 9 | (7.1) | |

| T2c | 516 | (17.5) | 56 | (27.5) | 10 | (2.1) | 102 | (21.1) | 334 | (19.9) | 14 | (11.1) | |

| n. d. | 7 | (0.2) | 0 | – | 0 | – | 2 | (0.4) | 5 | (0.3) | 0 | – | |

| Gleason score | <0.01* | ||||||||||||

| ≤ 6 | 1713 | (57.9) | 91 | (44.6) | 433 | (92.5) | 266 | (54.7) | 859 | (51.3) | 64 | (50.8) | |

| 7a (3+4) | 678 | (22.9) | 44 | (21.6) | 28 | (6.0) | 117 | (24.1) | 469 | (28.0) | 20 | (15.9) | |

| 7b (4+3) | 236 | (8.0) | 24 | (11.8) | 1 | (0.2) | 47 | (9.7) | 160 | (9.6) | 4 | (3.2) | |

| ≤ 8 | 259 | (8.8) | 43 | (21.1) | 1 | (0.2) | 49 | (10.1) | 161 | (9.6) | 5 | (4.0) | |

| n. d. | 71 | (2.4) | 2 | (1.0) | 5 | (1.1) | 7 | (1.4) | 24 | (1.4) | 33 | (26.2) | |

| Risk profile (d’Amico) | <0.01* | ||||||||||||

| Low | 1151 | (38.9) | 39 | (19.7) | 386 | (82.5) | 169 | (34.8) | 517 | (30.9) | 40 | (31.7) | |

| Intermediate | 965 | (32.6) | 66 | (32.4) | 62 | (13.2) | 165 | (34.0) | 630 | (37.7) | 42 | (33.3) | |

| High | 788 | (26.6) | 98 | (48.0) | 14 | (3.0) | 148 | (30.5) | 509 | (30.4) | 19 | (15.1) | |

| Not determinable | 53 | (1.8) | 1 | (0.5) | 6 | (1.3) | 4 | (0.8) | 17 | (1.0) | 25 | (19.8) | |

HT, Hormone withdrawal treatment; AS, active surveillance; RT, radiotherapy; OP, radical prostatectomy; WW, watchful waiting; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SD, standard deviation; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; n.d., no data; *, statistically significant

Active surveillance

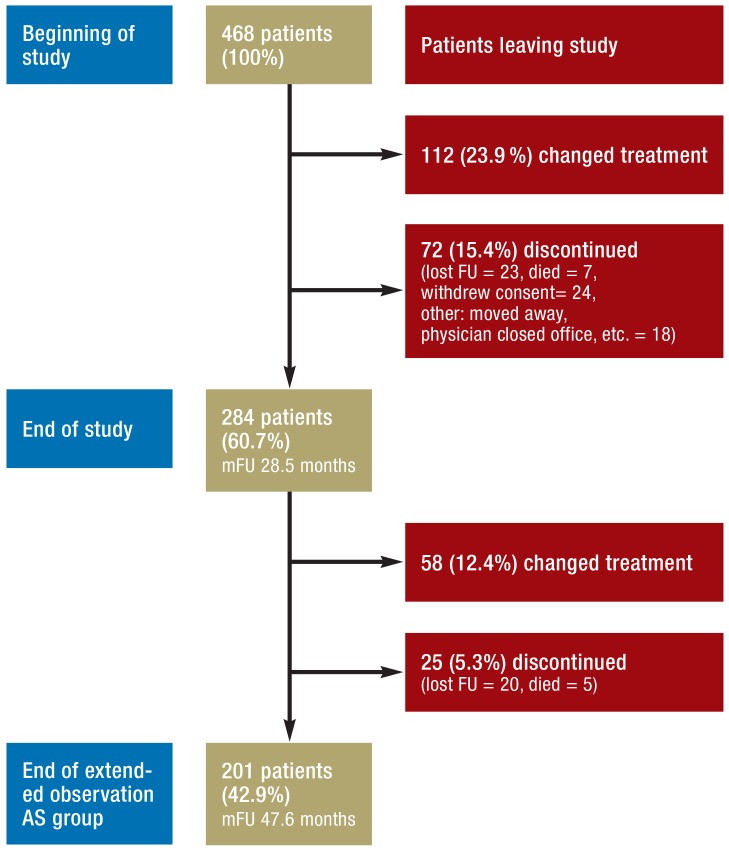

At the end of the HAROW study in July 2013, 284 (60.7%) of the original 468 patients were still under AS, 112 (23.9%) had switched to another treatment strategy, and 72 (15.4%) had left the study (Figure 1). The reasons for changing treatment were: upgrading on repeat biopsy (n = 52), increased PSA concentration (n = 32), the patient’s wish (n = 17), and the treating physician’s recommendation (n = 6). In five cases no reason was given.

Figure 1.

Active surveillance in the HAROW study

mFU, mean follow-up; lost FU, lost to follow-up

Follow-up of patients under AS was extended to April 2015. By that time a further 58 patients (12.4%) had switched to a different treatment strategy and 25 (5.3%) had left the study; the remaining 201 (42.9%) were still under AS. The treatments to which AS patients switched are shown in Figure 2. While OP predominated up to the end of the regular HAROW study, during the extended observation period changes to OP decreased in favor of WW.

Figure 2.

The various treatments after the end of active surveillance (AS) at the time of the end of the HAROW study (July 2013) and after extended observation of the AS group (April 2015). Of the 468 patients included in the AS group at the beginning of HAROW, 284 (60.7%) were still being treated with AS at the end of HAROW and 201 (42.9%) at the end of the extended observation period.

OP, Radical prostatectomy; RT, radiotherapy; HT, hormone treatment; WW, watchful waiting

Pathological data are available for 54 of the 65 patients who switched to OP before the end of the HAROW study: in 46 cases tumor growth was confined to the prostate, eight patients had a pT3a tumor, and none had a tumor ≥ pT3b. Twelve patients from the AS group died during this period—none of them from PCa.

Quality of life

The trends in global QoL—adjusted by patient characteristics—over a period of 3.5 years varied among the treatment groups (Figure 3). The AS group had the highest initial rating (75.56 points, 95% confidence interval [73.43; 77.69]) and maintained this level over time. Patients from the OP and RT groups had lower initial QoL (70.9 points, 95% CI [69.77; 72.03] and 72.82 points, 95% CI [70.52; 75.13] respectively), but over time they approached and eventually attained the level of the AS group. Significant differences between AS and OP were found only in the first year of the study (T0: p = 0.017 and T1: p = 0.018). Between AS and RT no significant differences were observed at all. HT patients had the lowest QoL score at the outset (65.52 points, 95% CI [61.92; 68.91]) and stayed practically constant over time. The QoL of patients in the WW group rose steadily up to T3 (1.5 years) but sank almost back to the initial level thereafter. Only at T3 was there a significant difference (p = 0.007) between WW and HT.

Figure 3.

Changes in global quality of life according to QLQ-C30 (EORTC) over 3.5 years stratified by treatment options; adjusted for the patient characteristics shown in Table 2

In some patients only the QoL data from the first time point could be ascertained. The number of patients included in analysis was n = 2258 at T0 and n = 494 at T7.

OP, Radical prostatectomy;

RT, radiotherapy; HT, hormone withdrawal treatment;

AS, active surveillance;

WW, watchful

waiting

95% CI, 95% confidence interval;

n, number of cases

Discussion

The role of invasive procedures in the treatment of localized PCa with a low risk profile remains to be clearly defined. The reasons for this lie in the biological characteristics of the tumor. Tumors with a Gleason score ≤ 6 appear to have hardly any potential for metastasis, so that OP or RT would represent overtreatment. Two studies, one from the 1980s and one from the 1990s, compared OP with non-intervention (WW) and came to different conclusions after observation for 10 and 13 years respectively. In the PIVOT study, carried out in the USA, the OP strategy achieved higher cancer-specific survival only in patients with an initial PSA concentration >10 ng/mL (11), while the Swedish SPCG-4 study demonstrated superiority of OP only in patients aged <65 years (12). More clinically apparent tumors were included in those studies than would be expected today, because now most tumors are detected by determination of PSA. In the SPCG-4 study 75% of the patients had a palpable tumor (≥ T2) and the mean PSA was 13.0 ng/mL. In comparison, the proportion of T2 tumors in the PRIAS study (recruiting only AS patients) is 14.9% (26) and in the HAROW study 39.1%; the mean PSA concentrations are 5.6 ng/mL and 9.4 ng/mL respectively.

HAROW: overall findings

The distribution of T category and the Gleason score in the HAROW study corresponds to the well-known stage shift: non-palpable tumors (≤ cT1c = 61.9%) with a Gleason score ≤ 6 (57.9%) predominate. This is comparable with data from other studies of localized PCa (14, 27). The allocation to the treatment groups shows correct differentiation between curative and palliative strategies, in that younger patients and those with a low CCI score were often treated with AS or OP, while the WW and HT groups are dominated by older patients with high CCI. The high proportion of patients with a low d’Amico risk profile in the AS group (82.5%) and the distinct differences in age and comorbidities between AS and WW seem to show that the participating physicians often selected the AS strategy in accordance with the S3 guideline or the HAROW recommendations. AS was chosen for 33.5% of the patients with a low risk profile, but the fact that OP was preferred for 44.9% of those in this risk category seems to support the overtreatment described in the literature (3, 9).

Active surveillance

Insight into everyday practice is provided by the frequency with which patients switch from AS to other treatment strategies. In a systematic review of 10 clinical AS series embracing a total of more than 3 500 patients, 33% of the patients switched to invasive treatments within the first 5 years (28); in the HAROW study it was 36.3% in just under 4 years. An interesting observation in the HAROW study is the shift from AS to WW. Many study physicians switched patients who for particular reasons (age, comorbidities) were no longer suitable for curative treatment or no longer desired it from AS to the palliative WW strategy. In the first 28.5 months 6.3% of the patients switched to WW, and by 47.6 months the figure was 15.9% (27/170).

Quality of life

Assuming that the various treatment options are oncologically equivalent in low-risk PCa, the anticipated adverse effects and their impact on the patient’s QoL become more important. The principal complications of OP are erectile dysfunction (29–100%) and stress incontinence (4–50%) (10), while RT is followed mainly by urogenital (34%) and gastrointestinal (30%) complications (29). Approximately 61% of patients treated with RT are affected by the late complication of erectile dysfunction within 2 years (30). In contrast, a recent systematic review found that patients treated by AS showed high QoL ratings in the absence of serious negative psychological consequences (31). An investigation into quality-adjusted life expectancy showed higher QoL for AS than for invasive forms of treatment (32). The HAROW study is the first in which QoL can be compared longitudinally across all five treatment options. Among the curative strategies, significantly lower QoL than in the AS group was found only for OP patients at T0 and T1, which can be explained by the intervention and the subsequent phase of convalescence. In the longer term, QoL did not differ significantly among the three curative treatments (AS, RT, OP).

Moreover, the lower QoL was significantly different only for OP patients at two time points (T0, T1). As for the palliative options, the pronounced increase in the QoL of patients in the WW group was seen particularly in the first 1.5 years. Thus, at least in the early phase of treatment there were distinct differences in QoL between WW and HT patients. The predominant lack of significance can be explained by the low case numbers of both groups. For this reason, early HT seems inappropriate in asymptomatic localized PCa, a view supported by the fact that a cohort study with 66 000 low-risk patients found no benefit of early HT in respect of cancer-specific survival (33). Only in patients with advanced PCa was immediate HT associated with improved progression-free survival.

In the AS group, the 88 patients who reached T7 had a QoL rating of 77.68 points at T0, higher than the mean QoL of all AS patients at T0 (75.56 points). This suggests positive selection (attrition bias), a problem that occurs mainly in groups with low numbers of patients. In the WW group, the 19 patients still left at T7 had a QoL rating of 72.22 points at T0 (mean for all WW patients at T0: 69.17 points). Attrition bias was also evident in the HT and RT groups.

Limitations

On the one hand, HCR data consistently yield a lower level of evidence than data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), largely because of less stringent inclusion criteria and the lack of comparison groups. On the other hand, HCR reflects more accurately the reality of healthcare, which cannot be simulated in RCTs (34). One limitation specific to HAROW is the observation period of 28.4 months (47.6 months for the AS group), relatively short when considering metastasis and tumor-specific mortality for a type of tumor with slow growth. The histological findings were not reviewed by a reference pathologist; however, this is rarely the case in everyday practice. The study physicians were not representative in that due to their participation in HAROW they were acquainted with the (then novel) AS strategy, meaning that bias cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

The results of the HAROW study show that the participating physicians differentiated clearly between curative and palliative treatment strategies. The preference for OP in the majority of tumors with a low risk profile clearly points to overtreatment. A treatment shift—away from OP towards AS—should be targeted in the near future. In addition to diagnosis and advice on management options, urologists in private practice are responsible for an essential part of the treatment in the form of AS. In this context, the revised S3 guideline recommends advancing the time of the first repeat biopsy from 12–18 months to 6 months (10). Since 2014, the British guidelines (35) stipulate multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging before AS.

In a situation where the outcomes of various treatment strategies can be assumed to be similar, non-ontological factors such as QoL, the practicability of treatments, and cost–benefit considerations assume special importance. Herein lies a task for HCR.

It remains to be seen whether the lack of differences in global QoL among the curative forms of treatment will be confirmed in the other dimensions of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (function and symptom scales).

Key Messages.

HAROW is the first German healthcare research study on localized prostate cancer.

The literature makes it clear that there is no need for invasive treatment of “low-risk” (≤ cT2a, Gleason score ≤ 6, PSA <10 ng/mL) prostate cancer.

The high proportion (44.9%) of patients with “low-risk” prostate cancer treated surgically points to overtreatment.

The inclusion criteria for active surveillance were widely observed.

The increase in prostate cancers with a favorable risk profile, resulting from the early detection of low-risk tumors and demographic trends, makes it likely that the defensive treatment options of active surveillance and watchful waiting will play a greater role in future.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Ethics committee approval

All investigations described in this article took place with the approval of the ethics committee of the Bavarian State Medical Association and adhered to German laws and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (current version). All participating patients gave written informed consent.

The HAROW study was initiated and conducted by the Foundation of Men’s Health and financially supported by Gazprom Germania.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Weißbach has acted as a paid consultant for the Scientific Institute (WIdO) of the AOK health insurance provider. He has received study support (third-party funding) from Gazprom Germania.

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interests exists.

References

- 1.RK. www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/DE/Content/Publikationen/Krebs_in_Deutschland/kid_2015/kid_2015_c61_prostata.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. (last accessed on 21 March 2016)

- 2.Pashayan N, Pharoah P, Neal DE, et al. Stage shift in PSA-detected prostate cancers—effect modification by Gleason score. J Med Screen. 2009;16:98–101. doi: 10.1258/jms.2009.009037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Reid B, et al. Addressing overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: a prescription for change. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e234–e242. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70598-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, et al. Fifteen-year outcomes following conservative management among men aged 65 years or older with localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.03.021. pii: S0302-2838(15)00230-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penney KL, Stampfer MJ, Jahn JL, et al. Gleason grade progression is uncommon. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5163–5168. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker C. Active surveillance: towards a new paradigm in the management of early prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:101–106. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross HM, Kryvenko ON, Cowan JE, Simko JP, Wheeler TM, Epstein JI. Do adenocarcinomas of the prostate with Gleason score (GS) ≤6 have the potential to metastasize to lymph nodes? Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1346–1352. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182556dcd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kweldam CF, Wildhagen MF, Bangma CH, van Leenders GJ. Disease-specific death and metastasis do not occur in patients with Gleason score ≤ 6 at radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2015;116:230–235. doi: 10.1111/bju.12879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeb S, Bjurlin MA, Nicholson J, et al. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65:1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.12.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft Deutsche Krebshilfe AWMF. Interdisziplinäre Leitlinie der Qualität S3 zur Früherkennung, Diagnose und Therapie der verschiedenen Stadien des Prostatakarzinoms. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/043-022OL.html. (last accessed on 7 June 2015)

- 11.Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:932–942. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parulekar WR, McKenzie M, Chi KN, et al. Defining the optimal treatment strategy for localized prostate cancer patients: a survey of ongoing studies at the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Curr Oncol. 2008;15:179–184. doi: 10.3747/co.v15i4.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lane JA, Donovan JL, Davis M, et al. Active monitoring, radical prostatectomy, or radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer: study design and diagnostic and baseline results of the ProtecT randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1109–1118. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiegel T, Albers P, Bussar-Maatz R, et al. PREFERE— the German prostatic cancer study: questions and claims surrounding study initiation in January 2013. Urologe A. 2013;52:576–579. doi: 10.1007/s00120-013-3186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scriba PC. [Health services research—physicians’ competence] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2005;130:1577–1578. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnell D, Schön H, Weissbach L. [Therapy of local prostate carcinoma. Questions answered by outcome research]. Urologe A. 2009;48:1050–1055. doi: 10.1007/s00120-009-2082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: trials and tribulations. World J Urol. 2008;26:437–442. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0330-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choo R, Klotz L, Danjoux C, et al. Feasibility study: watchful waiting for localized low to intermediate grade prostate carcinoma with selective delayed intervention based on prostate specific antigen, histological and/or clinical progression. J Urol. 2002;167:1664–1669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Bergh RC, Roemeling S, Roobol MJ, Roobol W, Schröder FH, Bangma CH. Prospective validation of active surveillance in prostate cancer: the PRIAS study. Eur Urol. 2007;52:1560–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent-update 2013. Eur Urol. 2014;65:124–37. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–974. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aaronson N, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, et al. 3rd Edition. Brussels: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bul M, van den Bergh RCN, Zhu X, et al. Outcomes of initially expectantly managed patients with low or intermediate risk screen-detected localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012;110:1672–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384:2027–2035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomsen FB, Brasso K, Klotz LH, Røder MA, Berg KD, Iversen P. Active surveillance for clinically localized prostate cancer - a systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:830–835. doi: 10.1002/jso.23584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldner G, Bombosch V, Geinitz H, et al. Moderate risk-adapted dose escalation with three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy of localized prostate cancer from 70 to 74 Gy. First report on 5-year morbidity and biochemical control from a prospective Austrian-German multicenter phase II trial. Strahlenther Onkol. 2009;185:94–100. doi: 10.1007/s00066-009-1970-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potosky AL, Legler J, Albertsen PC, et al. Health outcomes after prostatectomy and radiotherapy for prostate cancer: results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1582–1592. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellardita L, Valdagni R, van den Bergh R, et al. How does active surveillance for prostate cancer affect quality of life? A systematic review. Eur Urol. 2015;67:637–645. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayes JH, Ollendorf DA, Pearson SD, et al. Active surveillance compared with initial treatment for men with low-risk prostate cancer: a decision analysis. JAMA. 2010;304:2373–2380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, et al. Fifteen-year survival outcomes following primary androgen-deprivation therapy for localized prostate cancer. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1460–1467. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schrappe M, Pfaff H. [Health services research: concept and methods] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2011;136:381–386. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1272540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. NICE clinical guideline 175. Prostate cancer: diagnosis and treatment. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg175/chapter/1-recommendations#localised-and-locally-advanced-prostate-cancer-2. (last accessed on 21 April 2015)