Abstract

Background:

Early recognition of mental health problems gives an individual the opportunity for better long-term outcomes if intervention is initiated early. Mental health literacy is a related concept which is increasingly seen as an important measure of the awareness and knowledge of mental health disorders.

Aim and Objectives:

This study aimed at assessing the mental health literacy, help-seeking behavior and beliefs and attitudes related to mental illnesses among adolescents attending preuniversity colleges.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among randomly selected preuniversity college students (n = 916). Data were collected through self-administered questionnaires. Data were computed using STATA. Analysis and interpretation were carried out using descriptives and Chi-square test.

Results:

Of the 916 respondents, 54.15% were male while 45.85% were female. The majority (78.60%) of the respondents ascribed to the Hindu religion, hailed largely from rural areas (57.21%) and were mostly studying in the 11th standard (72.49%). The percentage of mental health literacy among the respondents was very low, i.e., depression was identified by 29.04% and schizophrenia/psychosis was recognized by 1.31%. The study findings indicate that adolescents preferred reaching out more to informal sources including family members such as mothers than formal sources for self than for others indicating deeply prevalent stigmatizing attitudes toward mental health conditions.

Conclusions:

There is a need for immediate improvement in the knowledge of adolescents on mental health literacy which suggests that programs need to be developed such that adolescents can seek help from valid resources if the need were to arise and have appropriate knowledge on whom to approach for help.

Keywords: Adolescents, depression, help seeking, mental health literacy, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Mental health conditions are major contributors to the disease burden globally (14%).[1,2,3,4,5,6] The World Health Organization in 2002 reported estimates that depression affects about 154 million people while schizophrenia affects about 25 million globally.[7] Mental disorder is sometimes believed to be incurable which can cause delay or prevention for help seeking and can be damaging.[8,9]

The prevalence of mental health conditions in India is at about 18-207/1000 population while about 2-3% are known to suffer from major mental illnesses.[10] A review by Bhola and Kapur identified 23 school-based studies with morbidities related to mental health ranging from 3.23% to 36.50%.[11,12] A related concept to mental health is mental health literacy.[13,14]

Research on mental health literacy in various parts of the globe among adolescents and young adults showed that about half of them aged 12-25 years identified depression correctly and about a quarter identified psychosis.[15,16,17,18] Mental health literacy has related components including recognition and identification of mental health disorders and help seeking, knowledge on prevention of mental disorders, strategic knowledge about seeking self-help, knowledge regarding treatment and skills on how to provide support and first aid to others.[15,19] In the context of adolescents, help seeking ensures obtaining timely support and treatment. Literacy related to mental health is vital as about half of those who will develop mental disorders have their first episodes before 18 years of age.[14,20,21] People with limited health literacy do have a limited understanding of health problems, poor use of preventive measures and poor disease management skills.[22,23,24,25]

A lack in appropriate knowledge pertaining to mental disorders can pose as a bottleneck to early interventions. Furthermore, poor and negative attitudes to people with mental illnesses may cause delays in help seeking for these conditions. Evidence shows that limited mental health literacy impacts negatively not only on help seeking but also on decision-making on treatment and compliance.[24,25]

About 20% of the world's population is made up of adolescents of whom about 85% reside in economically limited regions of the world.[26] Almost 243 million adolescents, i.e., 21% of the nation's population, call India home.[27] Adolescence is a vulnerable stage in life in which children are in transition from childhood to adulthood.[28] Mental health promotion among adolescents is appropriate as the first episodes of mental illnesses are known to emerge during adolescence and early adulthood with greater than half of all individuals having the first episode either in childhood or during adolescence.[29,30,31,32,33,34]

Empowering the vulnerable young to identify and seek help early for possible mental health related problems can help in the reduction of morbidity. This study attempted to assess mental health literacy and preferences regarding sources of help and general attitudes toward mental health conditions among late adolescents in Udupi Taluk, which is a highly literate region of Karnataka in Southern India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted between January and July 2014 among preuniversity colleges of Udupi Taluk, which is one of three taluks in Udupi District. The sample consisted of students within the 15-19 years age group in preuniversity colleges where they were studying in the 11th and 12th standard classes in either the science, commerce, or arts streams.

The sample size was calculated at 872 with the estimation of proportion considered at 50%, relative precision of 10%, confidence interval at 95%, design effect of 2, and a nonresponse rate of 10%. Stratified cluster sampling method was employed. The method for sample size calculation is discussed below. The participants covered during the study were 916. This was because more clusters had to be covered to reach the sample size.

Administrative approval for the study was obtained from the office of the Deputy Director of preuniversity Colleges. The list of all colleges in the taluk was obtained. The colleges were then stratified into three groups including Government, Private, and Government Aided Colleges from which individual colleges were selected using the simple random method. Ethical approval was taken from the Institutional Ethics Committee of a Tertiary Care Hospital. Written informed consent and adolescent assent were obtained before data collection.

Tools

The data were collected using a self-administered pretested semi-structured questionnaire. A questionnaire was developed covering the following domains: Sociodemographic profile, two case vignettes which described depression and schizophrenia and a questionnaire on help seeking as well as attitudes regarding mental health conditions.

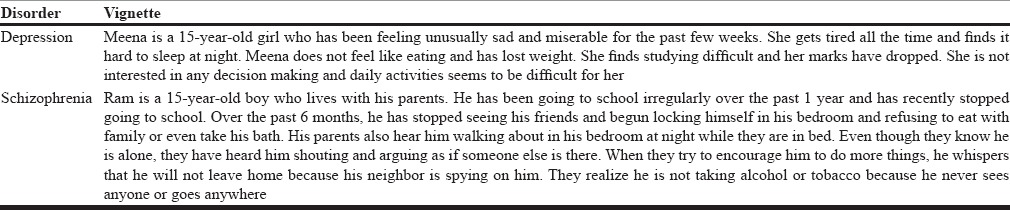

Questions were designed based on the National Survey of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma Youth Boost Survey V5 with permission from Reavley and Jorm.[35] In this study, the depression and schizophrenia vignettes [Table 1] were used with minimal modification from the original to fit the Indian context and was validated by experts in the field of clinical psychology and public health. The description of symptoms in the vignettes met that of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition diagnostic criteria for depression and schizophrenia. Questions were included on whether they could identify the mental disorder in the vignette and their beliefs regarding the sources of help and prevention as well as their opinion on the interventions. The questionnaire was first developed in English following literature review and was then translated into the local language, i.e., Kannada. To check for consistency, back translation into English was done. Tool validation was done by experts working in the field of public health, psychology, and psychiatric. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Descriptive data were reported for sociodemographic characteristics. Calculation of percentages and frequencies were done using STATA.

Table 1.

Case vignettes used in the study

RESULTS

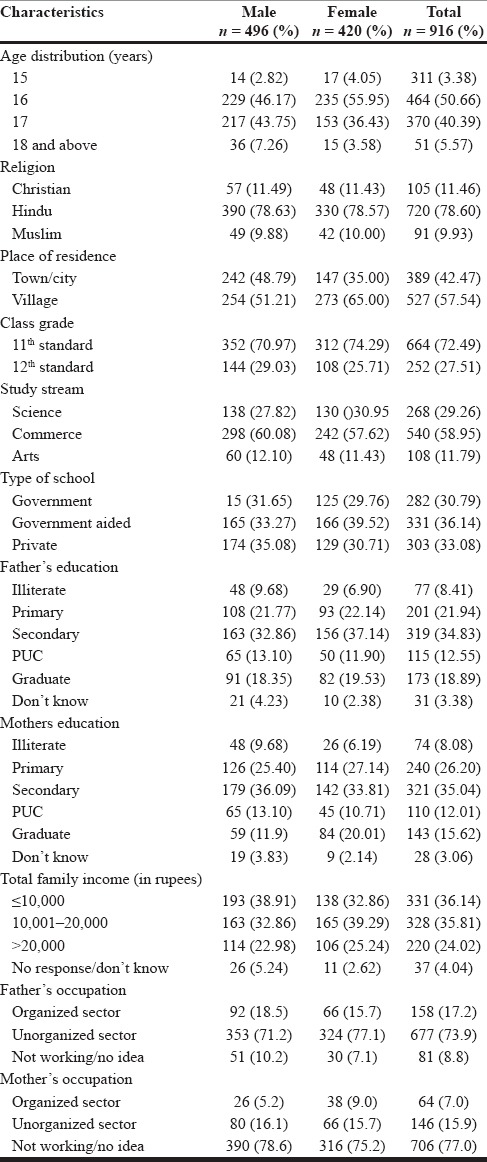

The descriptive information on the sociodemographic distribution of the participants summarized in Table 2 showed that of the 916 respondents, 54.15% were male while 45.85% were female. The majority (78.60%) of the respondents ascribed to the Hindu religion, hailed largely from rural areas (57.21%) and were mostly studying in the 11th standard (72.49%). About 58.95% studied in the commerce stream while 29.26% had chosen the science stream. The distribution of the respondents in government, government-aided, and private schools was 30.79%, 36.14%, and 33.08%, respectively.

Table 2.

Distribution of respondents according to their sociodemographic characteristics

There was wide variation observed regarding the parent's educational levels among the respondents. Around 8.41% of respondent's father and 8.08% of respondent's mother were illiterate. Most respondents' parents had completed secondary level of education. Variation in family income was also observed with 36.14% having family income of less than Rs. 10,000 ($150) per month while 4.04% respondents refused to state their family income. Most of the participant's fathers (73.9%) worked in the organized sector while most mothers were housewives (77%).

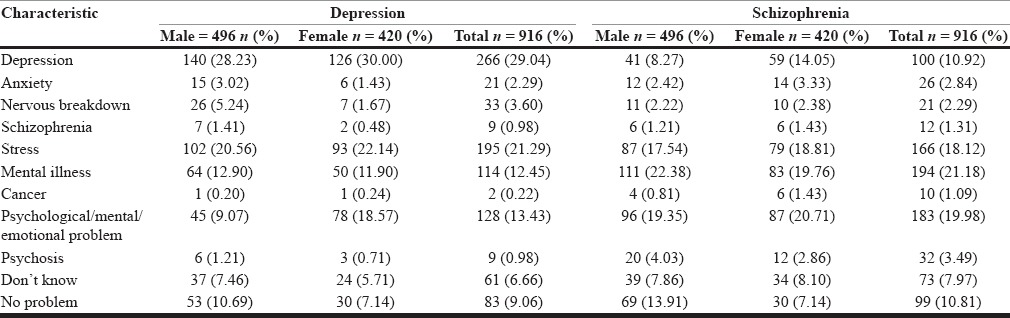

Mental health literacy assessed through the vignettes was very low with less than a third of the adolescents clearly identifying depression 29.04% and identification of schizophrenia was very low at 1.31%. Taking into consideration the young age of the respondents with the possibility of limited exposure to mental health conditions during their lifetime, alternative labels such as mental illness or psychological/mental/emotional problems were considered as indicative of understanding depressive conditions which amounted to an additional 25.88% and for schizophrenia, labels including psychosis, psychological/mental/emotional problem or mental illness were included which accounted for an additional 23.47% [Table 3].

Table 3.

Distribution of respondent's ability to identify mental health conditions

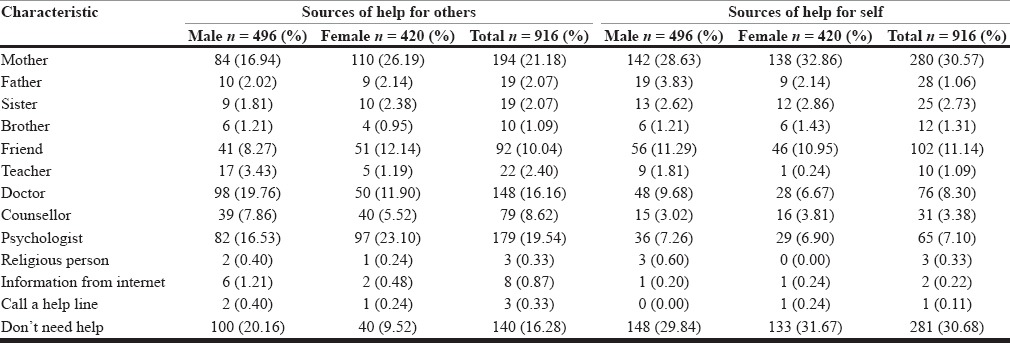

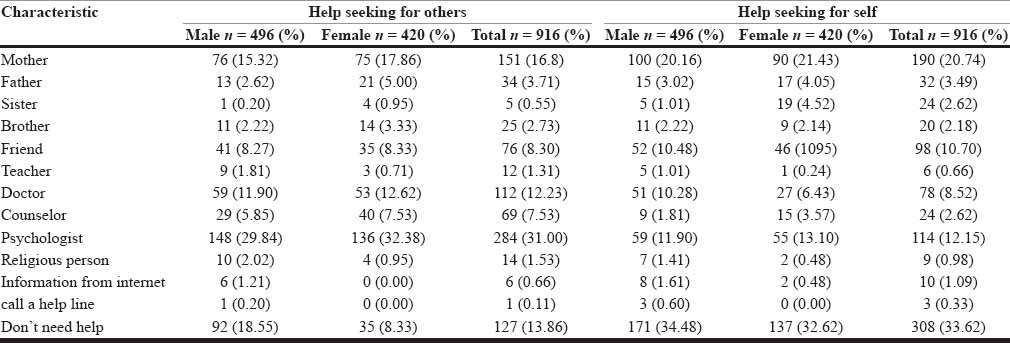

As observed from Table 4, the study findings on the preference of help seeking for depression indicates that adolescents preferred help both for self and others to a greater extent from family sources such as mothers (30.57% for self, 21.18% for others). For schizophrenia, similar findings included 20.74% for self and 16.8% for others' help seeking from mothers. On assessing for more formal sources of help for depression, psychologists were rated higher for others to seek help (19.54%) while it was comparatively lesser for self (7.10%). For schizophrenia, psychologists were thought to be good sources of help for others (31%) than for self (12.15%) [Table 5]. Health seeking from doctors again reflected similar findings for depression (8.30% for self and 19.54% for others) and for schizophrenia (8.52% for self and 12.23% for others) [Table 4]. Multiple choices were allowed for each respondent. However, ranking of the choices was not done. It was of concern that quite a large proportion felt that they would not need to seek help for either depression (30.68%) or schizophrenia (33.62%) [Table 5] if the situation arose. Most adolescents felt it was easier to seek help for others as opposed to help seeking for self (P = 0.037).

Table 4.

Sources of help seeking to address depression

Table 5.

Sources of help seeking to address schizophrenia

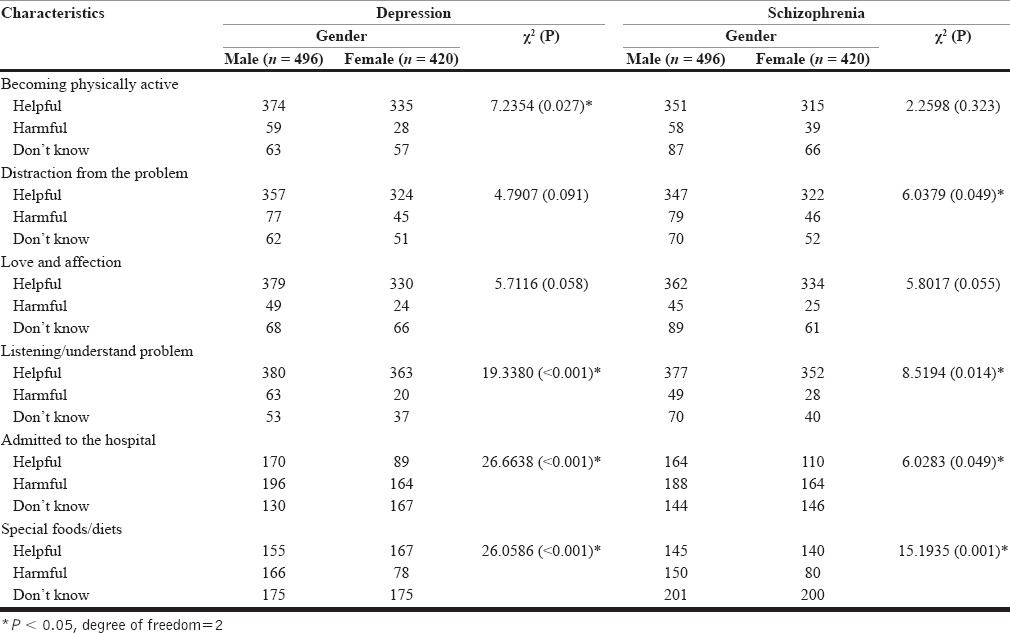

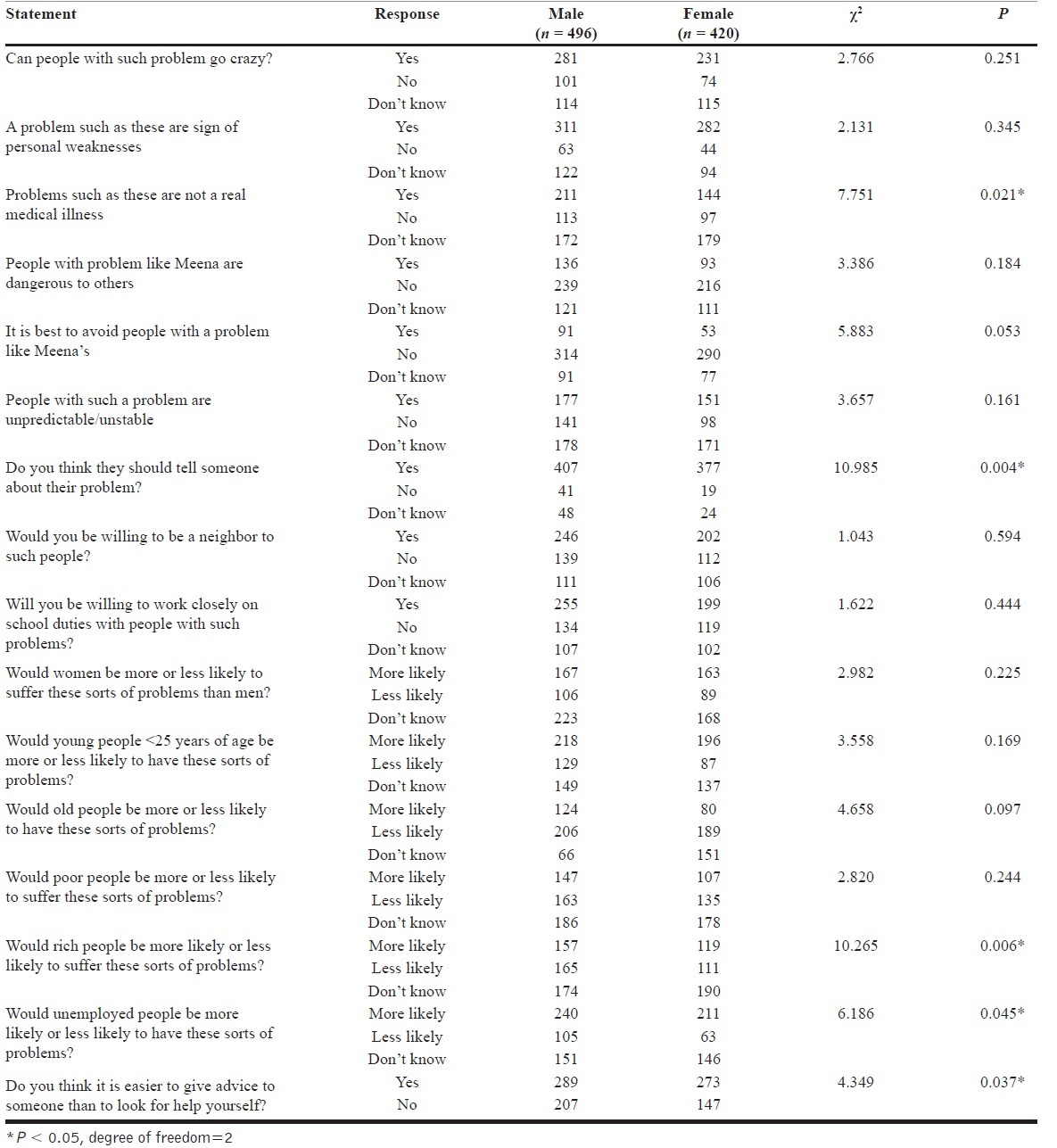

On assessing for attitudes toward strategies to prevent depression, becoming “physically active” (P = 0.027) and “listening to or understanding the problem” (P < 0.001) were rated by both genders as helpful. For schizophrenia, “distraction from the problem” (P = 0.049) [Table 6] and “listening to or understanding the problem” (P = 0.014) were though as helpful. Getting admitted to the hospital for depression was not thought to be helpful but was instead considered harmful by male adolescents (P < 0.001) and similar findings were obtained for both genders with regard to schizophrenia (P = 0.049) which could reflect societal attitudes towards seeking professional help for mental illnesses. Mental health conditions were not perceived as “real medical illnesses” by most of the male respondents (P = 0.021) while the majority in both genders thought they should tell someone about their problem (P = 0.004). On questions alluding to sections of the population who might be affected with mental health conditions more often, “the unemployed” were thought to more likely suffer from mental health conditions (P = 0.045) [Table 7].

Table 6.

Attitudes toward prevention of mental disorder for depression

Table 7.

Attitudes and beliefs toward mental disorders

DISCUSSION

This study aimed at assessing mental health literacy among adolescents and preferred help-seeking behaviors as well as attitudes towards mental health conditions in Udupi Taluk of Southern India.

Less than a third of the adolescents could clearly identify depression (29.04%) while identification of schizophrenia was even lower at 1.31%. In comparison, Lauber et al., in their study among Swiss population sampled between ages of 16 and 76 showed that about 40% recognized depression and 75% identified schizophrenia appropriately.[36] Correct identification of depression and schizophrenia in this sample was low. This could be related to the age of the sampled population which may reflect inadequate exposure and real-time experiences in relation to mental health conditions. Although India has a National Mental Health Program in place, school-based or targeted interventions related to mental health is largely lacking which could also indicate another important reason for low rates of identification of mental ill-health in this population. On adding alternate labels that were opted for depression, depression was identifiable by an additional 25.88%. Similarly, schizophrenia was additionally recognizable by 23.47% of the participants.

On assessing help seeking for mental health conditions, about 30.68% of the adolescents preferred not to seek help for possible mental health conditions with preferred sources of help being largely indicated as the mother. Professional help was relegated more for others than for self. In this study, teachers were not indicated as an important source of help. The poor need for help seeking for mental health conditions that emerge from this study could be an important indicator of the stigma related to mental health conditions reflecting the deeply entrenched attitude toward mental illnesses in Indian society.

An interesting finding was that male participants felt that mental illnesses were not “real medical illnesses.” Another interesting finding was that younger people and the unemployed were thought to more likely suffer from mental health conditions. Although these were not significant findings, they do reflect a lack of awareness. The attitude that mental conditions should not be brought out into the open is reflected by the results reflecting the deeply pervasive perceived stigma against mental health conditions in society.

CONCLUSIONS

The mental health literacy of participants in this study is study lower than desirable. The results from this study reflect the urgent need to increase awareness on mental health conditions, thus increasing opportunities for early help seeking and, in turn, detection and initiation of interventions early on while also contributing to better long-term mental health outcomes. These results reinforce findings by research in other parts of the globe. School-based health literacy programs have proven to have good outcomes in several settings.[37,38] Interventions targeting adolescents and stakeholders such as parents and teachers could prove to be the most effective form of intervention to reduce the burden of mental health conditions in the long-term. The pervasive stigma shrouding mental health conditions is an equally important fact that needs challenging and overcoming.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Department of Public Health, Manipal University, the Deputy Director for preuniversity colleges and the Principals of the preuniversity colleges in Udupi for giving us permission in conducting the study, our special thanks goes to all participants and parents/guardians of participants who gave the approval for their children/wards to participate in the study, without their approval this study would not have been a success. We are also grateful for the help extended by Dr. Anthony F. Jorm, PhD, DSc., at the University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Mental Disorders and the Need for a Comprehensive, Coordinated Response from Health and Social Sectors at the Country Level. Sixty-fifth World Health Assembly. WHA65.4 Agenda Item 13.2. [Last cited on 2015 Sep 09]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/WHA65.4_resolution.pdf .

- 2.Nimh.nih.gov. NIMH. Mental Illness Exacts Heavy Toll, Beginning in Youth. 2015. [Last cited on 2015 Sep 25]. Available from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2005/mental-illness-exacts-heavytoll-beginning-in-youth.shtml .

- 3.Ngui EM, Khasakhala L, Ndetei D, Roberts LW. Mental disorders, health inequalities and ethics: a global perspective. Int Rev Psychiatr. 2010;22:235–44. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.485273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright A, Harris MG, Wiggers JH, Jorm AF, Cotton SM, Harrigan SM, et al. Recognition of depression and psychosis by young Australians and their beliefs about treatment. Med J Aust. 2005;183:18–23. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotton SM, Wright A, Harris MG, Jorm AF, McGorry PD. Influence of gender on mental health literacy in young Australians. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:790–6. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust. 1997;166:182–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Depression. [Last cited on 2015 Sep 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/

- 8.Salve H, Goswami K, Sagar R, Nongkynrih B, Sreenivas V. Perception and Attitude towards Mental Illness in an Urban Community in South Delhi — A community based study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:154–8. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.116244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganesh K. Knowledge and attitude of mental illness among general public of Southern India. Natl J Community Med. 2001;2:175–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skre I, Friborg O, Breivik C, Johnsen LI, Arnesen Y, Wang CE. A school intervention for mental health literacy in adolescents: Effects of a non-randomized cluster controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:873. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhola P, Kapur M. Child and adolescent psychiatric epidemiology in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45:208–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srinath S, Girimaji SC, Gururaj G, Seshadri S, Subbakrishna DK, Bhola P, et al. Epidemiological study of child & adolescent psychiatric disorders in urban & rural areas of Bangalore, India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mental Health Literacy. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 12; Last updated on 2007 May];A Review of the Literature Bourget Management Consulting for the Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health. 2004 Nov; [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute of Health Mental Health. NIH 2005. Mental illness exacts heavy toll, beginning in youth. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 06]. Available from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2005/mental-illness-exacts-heavy-toll-beginning-in-youth.shtml .

- 15.Loureiro LM, Jorm AF, Mendes AC, Santos JC, Ferreira RO, Pedreiro AT. Mental health literacy about depression: A survey of portuguese youth. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrer L, Leach L, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Age differences in mental health literacy. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Mental health literacy as a function of remoteness of residence: An Australian national study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. [Last Cited on 2016 Jan 25];AF JORM Br J Psychiatry. 2000 177:396–40. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396. Available from http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/177/5/396 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawford G, Burns SK, Chih HJ, Hunt K, Tilley PJ, Hallett J, et al. Mental health first aid training for nursing students: a protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial in a large university. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:26. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabriel A, Violato C. Depression literacy among patients and the public: A literature review. Prim Psychiatry. 2010;17:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeppesen KM, Coyle JD, Miser WF. Screening questions to predict limited health literacy: A cross-sectional study of patients with diabetes mellitus. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:24–31. doi: 10.1370/afm.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lincoln A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Cheng DM, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Caruso C, Saitz R, et al. Impact of health literacy on depressive symptoms and mental health-related: Quality of life among adults with addiction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:818–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawlor E, Breslin JG, Renwick L, Foley S, Mulkerrin U, Kinsella A, et al. Mental health literacy among Internet users. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2008;2:247–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2008.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swami V. Mental health literacy of depression: Gender differences and attitudinal antecedents in a representative British sample. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. http://www.unicef.org/media/files/PFC2012_A_report_card_on_adolescents.pdf .

- 26.Sivagurunathan C, Umadevi R, Rama R, Gopalakrishnan S. Adolescent health: Present status and its related programmes in India. Are we in the right direction? J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:LE01–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11199.5649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao RS, Lena A, Nair NS, Kamath V, Kamath A. Effectiveness of reproductive health education among rural adolescent girls: A school based intervention study in Udupi Taluk, Karnataka. Indian J Med Sci. 2008;62:439–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Häfner H, Riecher A, Maurer K, Löffler W, Munk-Jørgensen P, Strömgren E. How does gender influence age at first hospitalization for schizophrenia? A transnational case register study. Psychol Med. 1989;19:903–18. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giedd JN, Keshavan M, Paus T. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:947–57. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones PB. Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2013;54:s5–10. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knapp P. First Onset of Serious Mental Illness and/or Psychosis in Transition Age Youth (TAY) [Last accessed on 2014 Jun 03]. Available from: http://www.cmhda.org/go/portals/0/cmhda%20files/committees/tay%20subcommittee/resource%20guide/final_(1-5-12)_first_onset_of_smi_final_format_[3-20-12]pdf .

- 33.Jones PB. Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(s54):s5–s10. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ochoa S, Usall J, Cobo J, Labad X, Kulkarni J. Gender differences in schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis: a comprehensive literature review. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2012;2012:916198. doi: 10.1155/2012/916198. doi: 10.1155/2012/916198. Epub 2012 Apr 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reavley NJ, Jorm AF. Young people's recognition of mental disorders and beliefs about treatment and outcome: Findings from an Australian national survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45:890–8. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.614215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauber C, Nordt C, Falcato L, Rössler W. Do people recognise mental illness? Factors influencing mental health literacy. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253:248–51. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adi Y, Killoran A, Janmohamed K, Stewart-Brown S. Systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to promote mental wellbeing in primary schools: Universal approaches which do not focus on violence or bullying. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diekstra R. Social and Emotional Education: An International Analysis. Santander: Fundacion Marcelino Botin; 2008. Effectiveness of school-based social and emotional education pro-grammes worldwide — Part one, a review of meta-analytic literature; pp. 255–84. [Google Scholar]