Abstract

Objective

The reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) rat model of preeclampsia was used to determine the effects of added interleukin-10 (IL-10) on Tregs and hypertension in response to placental ischemia and how the decrease in these anti-inflammatory factors mediates the pathophysiology of preeclampsia.

Methods

IL-10 (2.5 ng/kg/d) was infused via osmotic mini-pump implanted intraperitoneally on day 14 of gestation and, at the same time, the RUPP procedure was performed.

Results

IL-10 reduced mean arterial pressure (p<0.001), decreased CD4+ T cells (p = 0.044), while increasing Tregs (p = 0.043) which led to lower IL-6 and TNF-α (p = 0.008 and p = 0.003), reduced AT1-AA production (p<0.001), and decreased oxidative stress (p = 0.029) in RUPP rats.

Conclusion

These data indicate that IL-10 supplementation increases Tregs and helps to balance the altered immune system seen during preeclampsia.

Keywords: Hypertension, inflammation, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia (PE) affects 5–7% of pregnancies in the United States and is the leading cause of prenatal and maternal morbidity (1). PE is characterized by new onset hypertension during pregnancy and is associated with preterm labor and small for gestational age babies (2). In most cases, hypertension resulting from PE resolves after delivery, therefore, suggesting the placenta as a potential cause of the disease (3). Placental ischemia is thought to occur during PE as a result of shallow trophoblast invasion associated with imbalances between pro- and anti-angiogenic factors as well as pro and anti-inflammatory cytokines (1,3–6). The inflammation associated with placental ischemia is associated with increased pro-inflammatory cells and cytokines while regulatory immune cells and anti-inflammatory cytokines are suppressed. Inflammatory CD4+ T cells are significantly increased, while regulatory T cells are decreased leading to a chronic state of inflammation in PE women. Furthermore, others have shown that inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17 are all increased in women with preeclampsia, and regulatory cytokines like interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-4 are decreased (7–11). Data reported by other laboratories have also shown differences in the promoter region of the IL-10 gene that leads to decreased expression of IL-10 in the placenta which correlates to the development and progression of PE (12–14). Our laboratory has previously shown that placental explants from PE patients secrete lower levels of IL-10 in culture under normal oxygen and hypoxic conditions compared with placental explants from normal pregnant patients (15). These clinical data suggest that lowered immune regulatory factors could allow for the increase in pro-inflammatory factors (16).

Importantly, these symptoms develop in response to placental ischemia in the reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) rat model of preeclampsia. This immune imbalance during PE and in the RUPP rat is associated with the production of agonistic auto-antibodies to the AT1 receptor (AT1-AA) and endothelial dysfunction which we and others have shown that it plays a causal role in increasing blood pressure during pregnancy (3,17–23). The RUPP rat model of PE exhibits increased blood pressure and increased inflammatory CD4+ T cells and cytokines which lead to increased AT1-AA, endothelin-1 (ET-1), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (20,24). This increase in total CD4 + T cells is further characterized by decreased Tregs and increased TH17 cells (25,26).

Adoptive transfer studies of RUPP CD4+ T cells into NP rats conducted by our laboratory have demonstrated the importance of the imbalance in immune cells in causing hypertension through the endogenous production of AT1-AA, oxidative stress, and ET-1 (20,26). In addition, studies performed by our laboratory have also shown the benefits of suppressing inflammatory TH17 cells through infusion of the IL-17 receptor, which reduced blood pressure, oxidative stress, and AT1-AA, and increased pup and placenta weight in the RUPP model (27). These previous studies highlight the important role that the immune system plays during PE and provide evidence for immune suppression as a possible route of treatment for the disease. Since IL-10 is decreased in PE and it is responsible for anti-inflammatory actions such as regulating cytokine production and mediating naïve T cell differentiation, its likeliness to improve immune balance, blood pressure, and the consequences of PE needed to be further investigated.

IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine produced by many cells in the innate and adaptive immune system including dendritic cells, macrophages, T helper, and B cells (28–31). IL-10 behaves as a feedback regulator for a variety of immune responses including regulating inflammatory cytokine production and inflammatory cell activation or migration during the development of an immune response (32–34). Pro-inflammatory cytokines down-regulated by IL-10 include IFN-y, IL-2, and TNF-α. One important positive feedback response exists between IL-10 and its role to enhance differentiation of Tregs (35). IL-10 has been shown to prevent expression of pro-inflammatory transcription factors which decreases the differentiation of inflammatory cells, while inducing the expression of the Treg transcription factor, forkhead box protein 3 (Foxp3) which can lead to increasing TGF-β as a signaling molecule to further enhance regulatory T cells (36–38).

Previous studies have shown that IL-10 plays a role in vasculature function due to its ability to decrease inflammatory cytokines that lead to an increase in reactive oxygen species while promoting healing in the vasculature (39,40). These functions of IL-10 were shown to lead to a restoration of ET-1-dependent relaxation and increased eNOS expression in aortic rings (34,41). In addition, IL-10 has been shown to improve characteristics of PE in pregnant, DOCA/saline (PDS) rats by decreasing circulating ET-1 and IFN-γ, restoring aortic relaxation responses, decreasing proteinuria, and improving litter size following IL-10 treatment (40). In addition, hypoxia-induced preeclampsia-like symptoms were shown to be increased in IL-10 knockout animals, further illustrating the important role of IL-10 during normal pregnancy (42). In fact, others have shown that IL-10 deficiency exacerbates symptoms of preeclampsia and that exogenous IL-4 and IL-10 administration concurrently during pregnancy can alter immune cells subsets and prevent symptoms of PE in the PolyI:C pregnant mouse model (16,43). However, in these previous studies, the alteration in CD4 + T cells, Tregs, AT1-AAs, or oxidative stress was measured. Importantly, all these factors which are associated with PE are found in the RUPP model, and are potential endpoints to determine the effect of IL-10 supplementation to improve the pathophysiology associated with preeclampsia. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that IL-10 supplementation could restore immune balance by increasing Tregs which could lower inflammatory cytokines known to play a causal role in hypertension during pregnancy. Mediators of hypertension during pregnancy such as AT1-AA, preproendothe-lin-1 (PPET-1), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and inflammatory cytokines were measured in NP, RUPP, and RUPP+IL-10 rats.

METHODS

First timed pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley Inc. (Indianapolis, IN) were used in this study. Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room (23 °C) with a 12:12-h light/dark cycle. All experimental procedures executed in this study were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for use and care of animals. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Administration of IL-10 to NP and RUPP Rats

On gestational day 14, under isoflurane anesthesia, normal pregnant (NP) rats underwent a reduction in uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) with the application of a constrictive silver clip (0.203 mm) to the aorta superior to the iliac bifurcation performed while ovarian collateral circulation to the uterus was reduced with restrictive clips (0.100 mm) to the bilateral uterine arcades at the ovarian end. Rats were excluded from the study when the clipping procedure resulted in total reabsorption of the fetuses. IL-10 (2.5 ng/d) (RnD Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was infused intraperitoneally from day 14 to day 19 of gestation via mini-osmotic pumps (model 2002, Alzet Scientific Corporation, Cupertino, CA) into normal pregnant (NP) and RUPP rats. The groups of rats examined in this study were normal pregnant (NP, n = 15) RUPP (n = 22), IL-10-infused RUPP (RUPP+IL-10, n = 33), and IL-10-infused NP controls (n = 6).

Measurement of Mean Arterial Pressure into Chronically Instrumented Conscious Rats

Under isoflurane anesthesia, on day 18 of gestation, carotid arterial catheters were inserted for blood pressure measurements. The catheters inserted are V3 tubing (SCI) which is tunneled to the back of the neck and exteriorized. On day 19 of gestation, arterial blood pressure was analyzed after placing the rats in individual restraining cages. Arterial pressure was monitored with a pressure transducer (Cobe III Tranducer CDX Sema, Birmingham, AL) and recorded continuously for 1 h after a 1-h stabilization period. The rats were placed under isoflurane anesthesia prior to blood, urine, and tissue collection. Tissues including kidneys, spleens, and placentas were harvested and weighed prior to being stored for future analysis. Pups were removed and weights were determined.

Determination of Circulating CD4+ and Regulatory T Cells

Circulating CD4+ T cell population was determined from peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) collected at day 19 of gestation from NP, RUPP, and RUPP+IL-10. We utilized flow cytometry to detect regulatory T cell populations, CD4+ or CD4+CD25+ FoxP3+ (Treg) cells, from NP, RUPP, and RUPP+IL-10 rats. At the time of harvest, plasma was collected and PBLs were isolated from plasma by centrifugation on a cushion of Ficoll-Hypaque (Lymphoprep, Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. For flow cytometric analysis, an equal number of leukocytes (1 × 106) were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with antibodies against rat CD4 and rat CD25 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). After washing, cells were labeled with secondary Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) and phycoerythrin with cyanin-5 (PE-Cy5; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) antibody for 30 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed, permeabilized, and stained with rabbit polyclonal Foxp3 conjugated to allophycocyanin (APC) (R&D Biosystems, Minneapolis, MN) for 30 min at 4 °C. As a negative control for each individual rat, cells were treated exactly as described above except they were incubated with anti-FITC, anti-PE-Cy4, and anti-APC secondary antibodies alone. Subsequently, cells were washed and resuspended in 500 μL of Rosswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium or FoxP3-specific buffer and analyzed for single and double staining on a Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). The percent of positive staining cells above the negative control was collected for each individual rat for both CD4+ and Tregs and mean values for each experimental group were calculated.

Determination of Circulating IL-10, IL-6, TGF-β, and TNF-α

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed in serum samples to determine cytokine levels. IL-6 and TNF-α levels were determined using 100 μL of serum in commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). All assays were carried out in accordance with directions of the manufacturer. The minimal detectable dose (MDD) for the IL-6 ELISA was 0.7 pg/mL with an intra-assay/inter-assay precision of 3.1% and 2.7% CV. The MDD for the TNF-α assay was 12.5 pg/mL with an intra-assay/inter-assay precision of 3.1% and 9.4% CV. IL-10 was measured from 50 μL of plasma utilizing the IL-10 ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The minimal detectable dose (MDD) for the IL-10 ELISA was 10.0 pg/mL with an intra-assay/inter-assay precision of 3.4% and 8.7% CV. To determine circulating TGF-β levels, serum was diluted 1:10 prior to adding 50 μL of each sample to the ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The range of detection for the TGF-β ELISA was 15.4–2000 pg/mL with an intra-assay/inter-assay precision of 2.4% and 8.2% CV.

Measurement of Circulating Nitrate–Nitrite

Forty μL of maternal plasma was used to measure circulating nitrate–nitrite (NOx) in each of the experimental groups. Levels were determined using the Caymen Chemical Nitrate–Nitrite Colorimetric Assay Kit (Ann Arbor, MI) and the assay was carried out in accordance with the directions of the manufacturer. Intra-assay/inter-assay precision was 2.7% and 3.4%.

Determination of Circulating AT1-AA

On day 19 of gestation, blood was collected and immunoglobulin was isolated from 1 mL of serum by epitope binding using a protein G column. This IgG fraction was used in a bioassay. The AT1-AA activity was measured using spontaneously beating neonatal rat cardiomyocytes and characterized and antagonized specifically using AT1 receptor antagonists. The results express the difference between the basal beating rate of the cardiomyocytes and the beating rate measured after the addition of the AT1-AA (an increase in the number of beats/min or Δ beats/min) (18,23,44–47). AT1-AAs were assessed in sera of NP, RUPP controls, and RUPP + IL-10-treated rats.

Determination of Placental Preproendothelin mRNA Levels

Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was utilized to determine tissue preproendothelin-1 levels. Placentas were isolated, weighed, and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. The tissues were then stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was extracted from the tissues using the RNeasy Protect Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The isolation procedure was performed according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA). qRT-PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The following primer sequences provided by Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA) were used for PPET as previously described: forward 1, ctaggtctaagcgatccttg, and reverse 1, tctttgtctgcttggc. Levels of mRNA were calculated using the mathematical formula 2−ΔΔCt (2avg. Ct gene of interest − avg Ct beta actin) recommended by Applied Biosystems (Applied Biosystems User Bulletin, No. 2, 1997, Foster City, CA).

Determination of Placental ROS

Superoxide production in the placenta was measured by using the lucigenin technique as we have previously described (45,48). Rat placentas from NP, RUPP, and RUPP + IL-10 rats were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection and stored at −80 °C until further processing. Placentas were removed and homogenized in RIPA buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and a protease inhibitor cocktail; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA) as described previously (45,48). The samples were centrifuged at 16 000g for 30 min, the supernatant was aspirated and the remaining cellular debris were discarded. The supernatant was incubated with lucigenin at a final concentration of 5 μmol/L. The samples were allowed to equilibrate for 15 min in the dark, and luminescence was measured every second for 10 s with a luminometer (Berthold, Oak Ridge, TN). Luminescence was recorded as relative light units (RLU) per min. An assay blank with no homogenate but containing lucigenin was subtracted from the reading before transformation of the data. Each sample was repeated five times and the average used for data transformation. The protein concentration was measured using a protein assay with BSA standards (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The data are expressed as RLU/min/mg protein.

Statistical Analysis

All the data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons of control with experimental groups were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc analysis. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Determination of IL-10 Levels in NP, RUPP, and RUPP+IL-10 Rats

IL-10 supplementation increases circulating levels of IL-10 in RUPP rats to that observed in NP rats. Plasma from n = 4 animals from NP, RUPP, and RUPP+IL-10 groups was analyzed for circulating IL-10. IL-10 in NP was 52.2 pg/mL, decreased to 22.4 pg/mL in RUPP animals, but was increased to 65.6 pg/mL in rats supplemented with IL-10 (p<0.1).

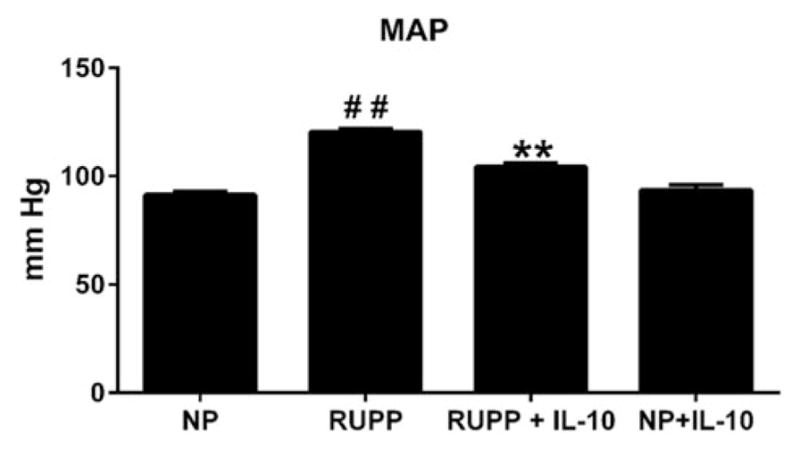

Effect of IL-10 Administration to RUPP Rats on Blood Pressure and Fetal Weight

Although IL-10 supplementation did not completely restore blood pressure to normal pregnant (NP) levels, RUPP rats treated with IL-10 exhibited a significant decrease in blood pressure compared with RUPP controls. NP rats (n = 15) had a MAP of 92 ± 2 mmHg, control RUPP rats (n = 22) had a significantly higher MAP of 120 ± 2 mmHg (p<0.001, versus NP), and RUPP rats given IL-10 (n = 33) had a MAP of 107 ± 2 mmHg, which was significantly lower than RUPP controls (p<0.001, Figure 1). There was no difference in MAP noted between NP and NP+IL-10 controls (MAP=93.5). Pup weight was also measured between the four groups of animals. Pup weight for NP animals was 2.25 g, but was significantly decreased to 1.99 g in RUPP animals. IL-10 supplementation, however, did not improve pup weight or reabsorptions in RUPP rats (RUPP+IL-10 = 1.94 g). There was no difference in NP and NP +IL-10 pup weight (NP+IL-10 = 2.3 g).

Figure 1.

IL-10 reduced blood pressure in RUPP animals, but did not improve pup weight. Compared with NP animals, RUPP show an increase in MAP. When RUPP animals were infused with IL-10, however, blood pressure significantly decreased (##, **p<0.001). There was no change in MAP seen in the NP+IL-10 group.

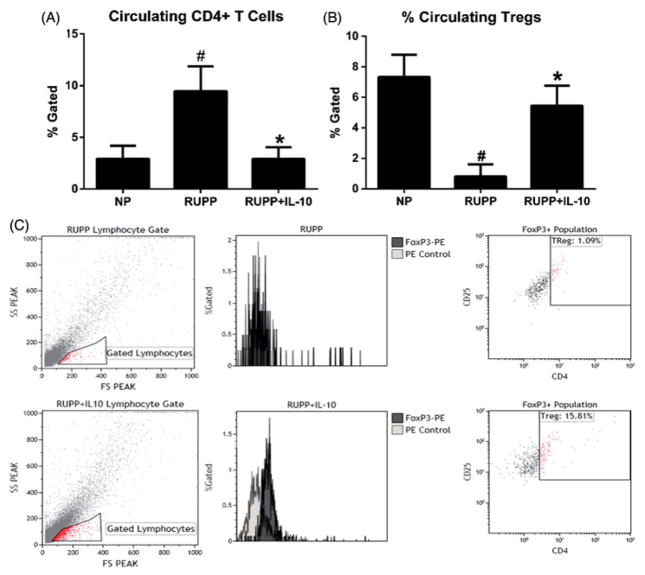

Circulating Tregs Increased with IL-10 Administration

The percentage of blood leukocytes stained positive for CD4+ in NP rats was 2.9% gated (n = 5), 9.5% in untreated RUPP animals (n = 8), and decreased to 2.5% gated in the IL-10-treated RUPP group (n = 7; p<0.05; Figure 2A). Importantly, IL-10 supplementation significantly increased the percentage of circulating Tregs in RUPP rats to levels similar to NP rats. Tregs in RUPP animals was 0.8% gated compared with 7.3% gated in NP animals and was 5.5% gated in RUPP+IL-10 animals (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

IL-10 supplementation significantly decreased circulating CD4 + T cells and significantly increased Tregs in RUPP rats. RUPP animals demonstrate significantly increased CD4 + T cells and reduced Tregs, but this imbalance was blunted in IL-10-treated animals. (A) CD4 + T cells were significantly reduced in IL-10-treated animals (n = 6–9/group). (B) In addition to decreasing CD4 + T cells, IL-10 significantly increased the number of Tregs, which we expected to provide increased regulatory function and to decrease downstream pathophysiology associated with placental ischemia (#, *p<0.05). (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood leucocytes (PBL) for TReg population. Blood leucocytes were stained for CD25, CD4, and FoxP3 expression. Cells were analyzed for allophycocyanin (APC) to identify the FoxP3 population prior to determining the percent of the cells that were also CD4 and CD25 positive. Tregs were measured as CD4+/CD25+/FoxP3+ as represented in the top, right quadrant of the flow plot.

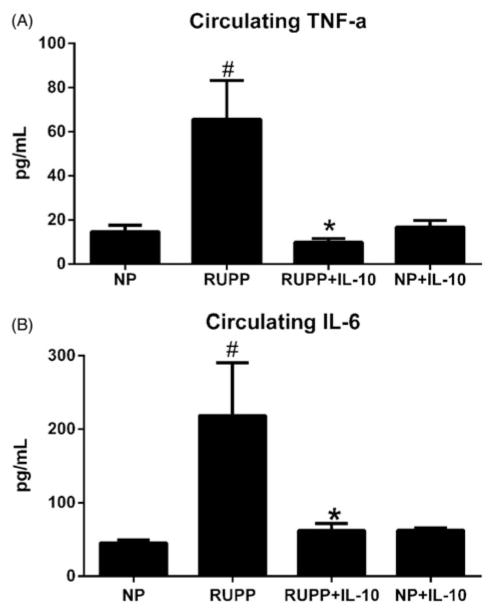

Circulating TNF-a and IL-6 were Decreased in RUPP+IL-10 Rats

Since one role of IL-10 is to regulate inflammatory cytokines, we measured levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in NP, RUPP, RUPP+IL-10, and NP+IL-10 rats. TNF-α levels were 14.7 ± 3 pg/mL for NP rats (n = 12), increased to 65.6 ± 18 pg/mL in RUPP rats (n = 12, p<0.05 versus NP), was significantly lowered to 10.0 ± 2 pg/mL in RUPP+IL-10 rats (n = 12, p<0.05 versus RUPP, Figure 3A) and was not significantly different in NP+IL-10 animals (NP+IL-10 = 16.8 ± 3 pg/mL). A similar trend was seen in levels of circulating IL-6 where NP (n = 12) rats had 45.5 ± 4 pg/mL, increased to 218.5 ± 72 pg/mL in RUPP animals (n = 12, p<0.05 versus NP), was significantly reduced to 62.4 ± 9 pg/mL in RUPP rats treated with IL-10 (n = 12, p<0.05 versus RUPP) and was not significantly different compared with NP in NP+IL-10 animals (NP+IL-10 = 62.7 ± 3; Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

IL-10 significantly reduced circulating inflammatory cytokines in RUPP animals. RUPP rats have increased levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to NP rats. (A) RUPP animals treated with IL-10 had significantly reduced circulating levels of TNF-α and (B) IL-6 compared with control RUPP rats. (#, *p<0.05). There was no change noted in NP+IL-10 animals versus NP rats for either circulating inflammatory cytokine.

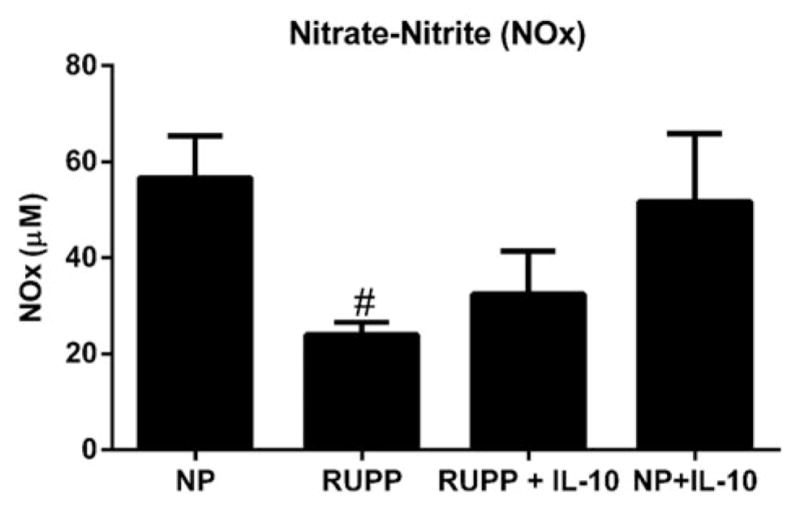

Effect of IL-10 on NO in RUPP Rats

Nitric oxide (NO) was measured indirectly in NP, RUPP, RUPP+IL-10, and NP+IL-10 groups through assessment of nitrate/nitrite (NOx) concentration. NP rats had NOx levels of 56.7 ± 8.7 μM, The levels of RUPP in rats were significantly decreased to 24.0 ± 2.5 μM, and although not significant, RUPP+IL-10 NOx was slightly improved to 32.5 ± 9 μM. NP+IL-10 rats demonstrated levels of NOx similar to NP rats (NP+IL-10 = 51.7 ± 14 μM; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Nitrate-nitrite (NOx) was increased in IL-10-treated rats. RUPP rats had significantly decreased levels of NOx versus NP rats. IL-10 supplementation in RUPP rats increased the presence of NOx; however, this finding was not significant (p = 0.1). There was no change in NOx seen in NP+IL-10 and NP rats.

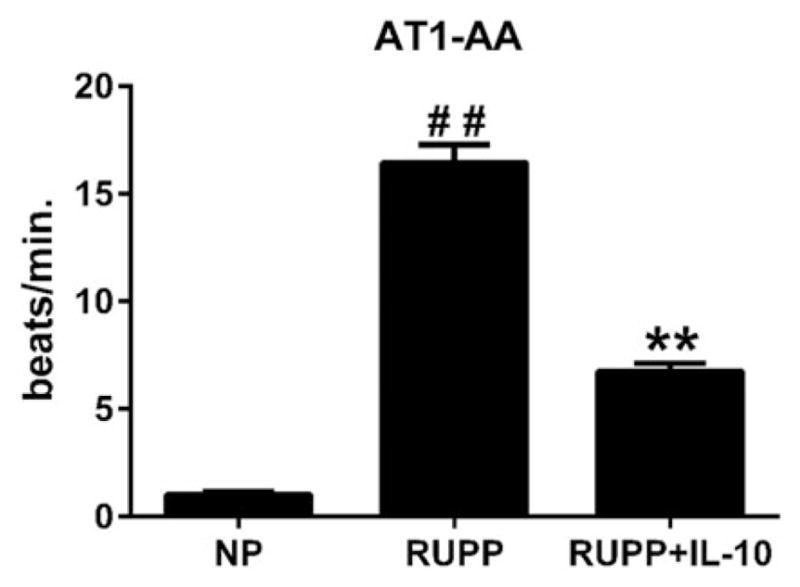

AT1-AA Production was Significantly Reduced with IL-10 Administration

Autoantibodies to the AT1 receptor are increased during preeclampsia and are increased in the RUPP rats as well. Analysis of serum from animals in each of the three groups showed that the AT1-AA activity of the RUPP rats (n = 6) was an average of 16.5 beats per minute (bpm) compared with 1.0 bpm in NP rats (n = 6, p<0.001), which were reduced to 6.8 bpm in RUPP+IL-10 (n = 8, p<0.001, Figure 5). AT1-AA is not produced in normotensive pregnant rats and due to a lack of an increase in blood pressure, TNF alpha, or IL-6 in response to IL-10 infusion, AT1-AA was not measured in the NP+IL10 group.

Figure 5.

Antibodies to the AT1 receptor were significantly reduced in IL-10-treated RUPP animals. While the production of AT1-AA was not completely attenuated in the RUPP rats supplemented with IL-10, AT1-AA was significantly reduced with IL-10 (##, **p<0.001).

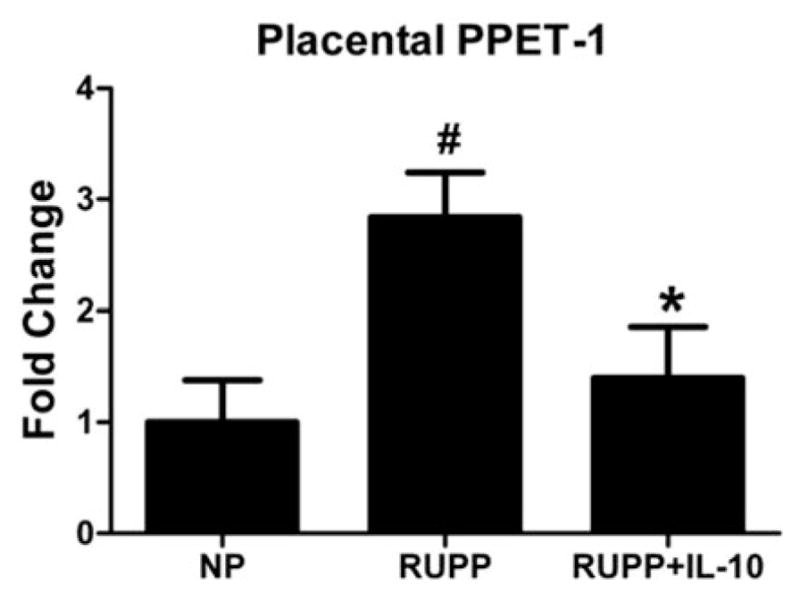

Placental ET-1 Decreased in Response to IL-10 Administration

ET-1 is a marker of endothelial dysfunction and a potent vasoconstrictor that plays a role in the regulation of blood pressure. Placental ET-1 is increased in RUPP rats compared with NP rats. Placental ET-1 was 2.5-fold higher in RUPP placentas (n = 6) compared with NP placentas (n = 7, p<0.05), but only a 1.4-fold increase in the ET-1 expression was seen in the IL-10-treated RUPP rats (n = 8, p<0.05 versus RUPP, Figure 6). Placental ET-1 is not increased in normotensive pregnant rats and due to a lack of an increase in blood pressure, TNF alpha or IL-6 in response to IL-10 infusion, ET-1 was not measured in the NP+IL10 group.

Figure 6.

IL-10 administration significantly reduced the expression of placental pre-proendothelin-1 (PPET-1) in RUPP rats. qRT-PCR analysis of placental PPET-1 showed that RUPP animals had significantly increased expression compared with NP rats; however, with IL-10 infusion, these expression levels were significantly reduced to levels similar to those seen in NP rats (#,*p<0.05).

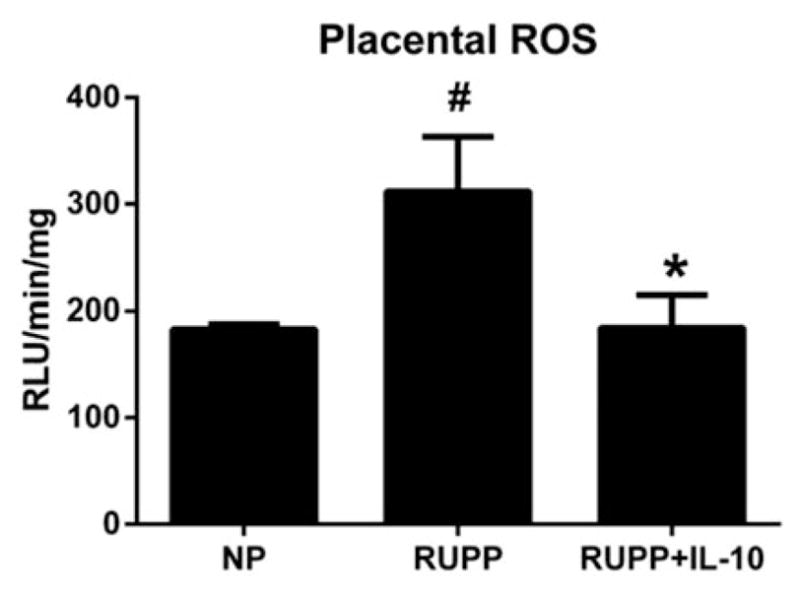

IL-10 Decreased Placental Oxidative Stress in RUPP Rats

Analysis of placental oxidative stress showed basal levels of ROS for NP animals to be 64.8 ± 2 RLU/min/mg (n = 6), RUPP animals had increased basal levels of 103.0 ± 26 RLU/min/mg (n = 9, p<0.05 versus NP) which was significantly reduced to 65.1 ± 13 RLU/min/mg in RUPP+IL-10 rats (n = 7, p<0.05 versus RUPP). With the addition of NADPH oxidase, the NP control group had levels of 183 ± 5 RLU/min/mg, the RUPP group was increased to 312 ± 52 RLU/min and the RUPP+IL-10-treated group was significantly decreased to 184 ± 30 RLU/min/mg compared with RUPP controls (p<0.05 versus RUPP, Figure 7). ROS is not elevated in normotensive pregnant rats and due to a lack of an increase in blood pressure, TNF alpha or IL-6 in response to IL-10 infusion, ROS was not measured in the NP+IL-10 group.

Figure 7.

Placental oxidative stress was significantly reduced in IL-10-treated animals. ROS was measured in placentas of animals from each of the three groups and was shown to be increased in RUPP animals compared with NP rats, but was significantly reduced in placentas from RUPP animals infused with IL-10 (#, *p<0.05).

IL-10 Increased TGF-β in NP and RUPP Rats

TGF-β has been shown to be increased during PE, but the pleiotropic cytokine also plays a role in the programming of Tregs and could be increased in response to IL-10 infusion. Circulating TGF-β was measured in NP, RUPP, RUPP+IL-10, and NP+IL-10 animals (n = 4/group) and was increased in RUPP animals versus NP rats (926.4 pg/mL versus 668.3 pg/mL), although not significantly. TGF-β was further increased with IL-10 to 1442.7 pg/mL in RUPP+IL-10 and 1695.2 pg/mL in NP+IL-10 animals.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the effect of supplementing RUPP rats, a model of preeclampsia (PE), with anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 on characteristics of PE such as hypertension, pro-inflammatory cytokines, AT1-AA, ET-1, and ROS. IL-10 supplementation to RUPP rats overall lowered the number of circulating CD4 + T cells while increasing the population of circulating Tregs to numbers similar to NP rats. In addition to normalizing Tregs, IL-10 decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6. Importantly, supplementation of IL-10 to RUPP rats significantly lowered AT1-AA, placental ROS, and ET-1 which proved beneficial in decreasing blood pressure during pregnancy. NP rats supplemented with IL-10 exhibited no changes in circulating inflammatory cytokines or blood pressure; therefore, mediators of hypertension during pregnancy such as AT1-AA, ROS, and ET-1 were not determined in this group.

While the data regarding levels of circulating TGF-β during PE is not consistent, some studies have shown the cytokine to be increased during PE (49–51). Since activated platelets occur in some women with PE and are known to produce TGF-β, this would explain why some researchers see an increase in TGF-β during the disease (51). This could be an explanation for the increase in TGF-β seen in the RUPP rats; however, platelets were not examined in this study, or have they been shown to be increased by others. Importantly, TGF-β, along with IL-10, is also responsible for Treg production from naïve T cells (53). There was a tendency or TGF-β to increase in both RUPPs and NP rats treated with IL-10. Furthermore, Tregs were increased in RUPP+IL-10 rats compared with RUPP which could be a result of the increased TGF-β or the increase in TGF-β could be a result of stimulated Tregs in RUPP+IL-10 (36,52,53). Nevertheless, TGF-β is necessary for the stimulation and proliferation of Tregs and thereby demonstrates the functional mechanism whereby IL-10 could improve the inflammatory cascade during pregnancy without causing harmful effects. If IL-10 induces transcription of FoxP3, thereby eliciting Tregs then their secretion of TGF-β would further support proliferation of new Tregs further improving the inflammatory cascade. Therefore, the overall importance of this study illustrates that IL-10 administration boosts regulatory T cells which leads to a more normal pregnant phenotype in pregnancies stricken with placental ischemia.

Our laboratory has previously shown that placental explants from PE patients secreted lower levels of IL-10 in culture under normal oxygen and hypoxic conditions compared with placental explants from normal pregnant patients (15). Lower levels of IL-10 during preeclampsia would allow for increased T cell activation and differentiation into a pro-inflammatory phenotype, thus, leading to an increased number of inflammatory T helper cells, cytokines, and possibly B cell stimulation. Increased B cells could lead to increased antibody production and, as we hypothesized, lead to the stimulation of autoantibodies to the angiotensin II receptor, type 1 (AT1-AA), which we have previously shown to increase blood pressure during pregnancy (3). In addition, B-cell depletion in RUPP rats caused lower AT1-AA and blood pressure in response to placental ischemia (45). In our current study, IL-10 supplementation, normalized T regulatory cells caused significant reductions in AT1-AA in response to placental ischemia. Furthermore, when treated with IL-10, RUPP rats had a significantly lower MAP than the untreated RUPP group, although not fully normalized to the degree of NP rats (Figure 2). We have previously shown that two mechanisms of hypertension stimulated by the AT1-AA activation of the AT1-receptor and through adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4 + T cells are ET-1 and placental oxidative stress, both of which are vasoactive mediators, and were reduced in RUPP rats treated with IL-10.

Previous investigators have shown that IL-10 supplementation improves blood pressure and endothelial function in the preeclamptic poly I:C pregnant mouse model (36). In addition, IL-10 supplementation also improves TLR3 expression in this mouse model, further supporting a role for IL-10 to improve inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and hypertension during pregnancy (44). Although in our study, IL-10 did not significantly improve NO formation, we demonstrate that IL-10 supplementation significantly lowers ET-1 and oxidative stress, two hallmark features in endothelial dysfunction during hypertension. In addition, our study further supports the previous findings suggesting a potential role for IL-10 supplementation to improve maternal signs of hypertension during pregnancy and could be further examined for novel therapeutics for PE.

Hypertension during PE involves many pathways and mechanisms that are possibly unrelated to IL-10. With the restrictive clip in place, normalizing blood pressure could be detrimental to the developing pup in the RUPP rats and could possibly be a protective compensatory mechanism in PE mothers. Therefore, the residual increase in blood pressure in the IL-10-treated group could be a compensatory response to spare pup growth and development in the RUPP rat model of PE. Furthermore, factors that were not measured, like sFlt or sEndoglin, could still be elevated in the RUPP rats treated with IL-10. These factors could potentially have contributed to maintaining the low pup weight in the IL-10-treated group by suppressing angiogenesis and further decreasing blood flow to the placenta while still causing endothelial cell activation, the residual increase in ET-1, and, therefore, hypertension in this model. In addition, although reduced, agonistic AT1-AAs were not normalized by IL-10 supplementation, which could also account for the residual increase in blood pressure and/or low pup weight.

Nonetheless, in ours and other models of pathological pregnancy, the supplementation of IL-10 proved to have a positive effect on the immune imbalance, vascular dysfunction, and hypertension normally seen (16). Although IL-10 administration to pregnant women may not be advocated, knowing what effect supplementation of IL-10 or stimulation of endogenous Tregs has in response to placental ischemia offers an avenue for future research in drug discovery geared to improve clinical management of PE. Studies conducted by our lab in the past showed a role for increased CD4 + T cells in PE, but further investigation into Treg mechanisms to improve the pathophysiology seen in response to placental ischemia is currently underway and will lend greater insight to the importance of a normal Treg response during pregnancy (26). This study demonstrated that normal immune regulatory pathways are essential to providing lowered blood pressure via lower levels of vasoactive substances such as ET-1, ROS, and AT1-AA, in pregnancies stricken with placental ischemia. Lower maternal blood pressures could lead to an overall improvement in maternal health which may promote increased time to delivery in preeclamptic pregnancies. Increased time to delivery for preeclamptic mothers is likely to improve fetal health, growth, and body weight of their babies as long as there is a relatively healthy intrauterine environment present.

PERSPECTIVES.

This mechanistic study demonstrates the important role that the imbalance in immune function and immune factors plays during placental ischemia. We believe that this imbalance is a result of placental ischemia and that the decreased immune regulatory cytokines and cells allow for the increase in inflammatory pathways that stimulate ET-1 expression, and increase ROS and AT1-AA, all of which contribute to the pathophysiology associated with preeclampsia. This study shows the importance of addition of the regulatory cytokine IL-10 to increase Tregs, thereby suppressing other proinflammatory factors that stimulate the pathophysiology of PE. While this study indicates IL-10 and Tregs as important factors in normal pregnancy, additional studies assessing the specific role of Tregs in improving the consequences of placental ischemia need to be performed.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

This work was supported by NIH Grants HL105324, HL124715, HL78147 and HL51971, and HD067541. R. D. is supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

References

- 1.George EM, Granger JP. Recent insights into the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5:557–66. doi: 10.1586/eog.10.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noris M, Perico N, Remuzzi G. Mechanisms of disease: pre-eclampsia. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2005;1:98–114. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0035. quiz 120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaMarca B, Wallace K, Granger J. Role of angiotensin ii type i receptor agonistic autoantibodies (at1-aa) in preeclampsia. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leik CE, Walsh SW. Neutrophils infiltrate resistance-sized vessels of subcutaneous fat in women with preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2004;44:72–7. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000130483.83154.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindheimer MD, Romero R. Emerging roles of antiangiogenic and angiogenic proteins in pathogenesis and prediction of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;50:35–6. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts JM, Lain KY. Recent insights into the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 2002;23:359–72. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncombe G, Veldhuizen RA, Gratton RJ, et al. Il-6 and tnfalpha across the umbilical circulation in term pregnancies: relationship with labour events. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:113–17. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma A, Satyam A, Sharma JB. Leptin, il-10 and inflammatory markers (tnf-alpha, il-6 and il-8) in pre-eclamptic, normotensive pregnant and healthy non-pregnant women. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58:21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhillion P, Wallace K, Herse F, et al. Il-17-mediated oxidative stress is an important stimulator of at1-aa and hypertension during pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul, Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;303:R353–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00051.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamarca B. The role of immune activation in contributing to vascular dysfunction and the pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia. Minerva Ginecol. 2010;62:105–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santner-Nanan B, Peek MJ, Khanam R, et al. Systemic increase in the ratio between foxp3 + and il-17-producing cd4+ t cells in healthy pregnancy but not in preeclampsia. J Immunol. 2009;183:7023–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makris A, Xu B, Yu B, et al. Placental deficiency of interleukin-10 (il-10) in preeclampsia and its relationship to an il10 promoter polymorphism. Placenta. 2006;27:445–51. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sowmya S, Ramaiah A, Sunitha T, et al. Evaluation of interleukin-10 (g-1082a) promoter polymorphism in preeclampsia. J Reprod Infertil. 2013;14:62–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sowmya S, Ramaiah A, Sunitha T, et al. Role of il-10-819(t/c) promoter polymorphism in preeclampsia. Inflammation. 2014;37:1022–7. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9824-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darby MM, Kedra W, Cornelius D, et al. Vitamin d supplementation suppresses hypoxia-stimulated placental cytokine secretion, hypertension and cd4+ t cell stimulation in response to placental ischemia. Med J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;1:1012–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterjee P, Chiasson VL, Seerangan G, et al. Cotreatment with interleukin 4 and interleukin 10 modulates immune cells and prevents hypertension in pregnant mice. Am J Hypertension. 2015;281:135–42. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dechend R, Gratze P, Wallukat G, et al. Agonistic autoantibodies to the at1 receptor in a transgenic rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2005;45:742–6. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000154785.50570.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dechend R, Homuth V, Wallukat G, et al. Agonistic antibodies directed at the angiotensin ii, at1 receptor in preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dechend R, Muller DN, Wallukat G, et al. Activating auto-antibodies against the at1 receptor in preeclampsia. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:61–5. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novotny SR, Wallace K, Heath J, et al. Activating autoantibodies to the angiotensin ii type i receptor play an important role in mediating hypertension in response to adoptive transfer of cd4+ t lymphocytes from placental ischemic rats. Am J Physiol Regul, Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R1197–201. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00623.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallukat G, Neichel D, Nissen E, et al. Agonistic autoantibodies directed against the angiotensin ii at1 receptor in patients with preeclampsia. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;81:79–83. doi: 10.1139/y02-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Granger JP, Alexander BT, Bennett WA, Khalil RA. Pathophysiology of pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am J Hypertension. 2001;14:178S–85S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaMarca B, Parrish M, Ray LF, et al. Hypertension in response to autoantibodies to the angiotensin ii type i receptor (at1-aa) in pregnant rats: role of endothelin-1. Hypertension. 2009;54:905–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaMarca BB, Bennett WA, Alexander BT, et al. Hypertension produced by reductions in uterine perfusion in the pregnant rat: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Hypertension. 2005;46:1022–5. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000175476.26719.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, LaMarca B, Reckelhoff JF. A model of preeclampsia in rats: the reduced uterine perfusion pressure (rupp) model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H1–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00117.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace K, Richards S, Dhillon P, et al. Cd4+ t-helper cells stimulated in response to placental ischemia mediate hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2011;57:949–55. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornelius DC, Hogg JP, Scott J, et al. Administration of interleukin-17 soluble receptor c suppresses th17 cells, oxidative stress, and hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2013;62:1068–73. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boonstra A, Rajsbaum R, Holman M, et al. Macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells, but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells, produce il-10 in response to myd88-and trif-dependent tlr signals, and tlr-independent signals. J Immunol. 2006;177:7551–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang HR, Muckersie E, Robertson M, et al. Secretion of interleukin-10 or interleukin-12 by lps-activated dendritic cells is critically dependent on time of stimulus relative to initiation of purified dc culture. J Leukocyte Biol. 2002;72:97885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw MH, Freeman GJ, Scott MF, et al. Tyk2 negatively regulates adaptive th1 immunity by mediating il-10 signaling and promoting ifn-gamma-dependent il-10 reactivation. J Immunol. 2006;176:7263–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jankovic D, Kullberg MC, Feng CG, et al. Conventional t-bet(+)foxp3(−) th1 cells are the major source of host-protective regulatory il-10 during intracellular protozoan infection. J Exp Med. 2007;204:273–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiorentino DF, Bond MW, Mosmann TR. Two types of mouse t helper cell. Iv. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by th1 clones. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2081–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu Y, Yang J, Ouyang X, et al. Interleukin 10 suppresses th17 cytokines secreted by macrophages and t cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1807–13. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gregori S, Tomasoni D, Pacciani V, et al. Differentiation of type 1 t regulatory cells (tr1) by tolerogenic dc-10 requires the il-10-dependent ilt4/hla-g pathway. Blood. 2010;116:935–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heo YJ, Joo YB, Oh HJ, et al. Il-10 suppresses th17 cells and promotes regulatory t cells in the cd4+ t cell population of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Immunol Lett. 2010;127:150–6. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lochner M, Peduto L, Cherrier M, et al. In vivo equilibrium of proinflammatory il-17+ and regulatory il-10+ foxp3+ rorgamma t+ t cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1381–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor rorgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory il-17+ t helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nevers T, Kalkunte S, Sharma S. Uterine regulatory t cells, il-10 and hypertension. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:88–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tinsley JH, South S, Chiasson VL, Mitchell BM. Interleukin-10 reduces inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and blood pressure in hypertensive pregnant rats. Am J Physiol Regul, Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R713–19. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00712.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zemse SM, Hilgers RH, Simkins GB, et al. Restoration of endothelin-1-induced impairment in endothelium-dependent relaxation by interleukin-10 in murine aortic rings. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86:557–65. doi: 10.1139/Y08-049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai Z, Kalkunte S, Sharma S. A critical role of interleukin-10 in modulating hypoxia-induced preeclampsia-like disease in mice. Hypertension. 2011;57:505–14. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chatterjee P, Chiasson VL, Kopriva SE, et al. Interleukin 10 deficiency exacerbates toll-like receptor 3-induced preeclampsia-like symptoms in mice. Hypertension. 2011;58:489–96. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.172114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dechend R, Homuth V, Wallukat G, et al. At(1) receptor agonistic antibodies from preeclamptic patients cause vascular cells to express tissue factor. Circulation. 2000;101:2382–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.20.2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.LaMarca B, Wallace K, Herse F, et al. Hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy: role of b lymphocytes. Hypertension. 2011;57:865–71. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.167569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parrish MR, Murphy SR, Rutland S, et al. The effect of immune factors, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and agonistic autoantibodies to the angiotensin ii type i receptor on soluble fms-like tyrosine-1 and soluble endoglin production in response to hypertension during pregnancy. Am J Hypertension. 2010;23:911–6. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parrish MR, Ryan MJ, Glover P, et al. Angiotensin ii type 1 autoantibody induced hypertension during pregnancy is associated with renal endothelial dysfunction. Gender Med. 2011;8:184–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parrish MR, Wallace K, Tam Tam KB, et al. Hypertension in response to at1-aa: role of reactive oxygen species in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am J Hypertension. 2011;24:835–40. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Madazli R, Aydin S, Uludag S, et al. Maternal plasma levels of cytokines in normal and preeclamptic pregnancies and their relationship with diastolic blood pressure and fibronectin levels. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:797–802. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ayatollahi M, Geramizadeh B, Samsami A. Transforming growth factor beta-1 influence on fetal allografts during pregnancy. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:4603–4. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perucci LO, Gomes KB, Freitas LG, et al. Soluble endoglin, transforming growth factor-beta 1 and soluble tumor necrosis factor alpha receptors in different clinical manifestations of preeclampsia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tran DQ. Tgf-beta: the sword, the wand, and the shield of foxp3(+) regulatory t cells. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4:29–37. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen W, Konkel JE. Tgf-beta and ‘adaptive’ foxp3(+) regulatory t cells. J Mol Cell Biol. 2010;2:30–6. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]