Abstract

Despite a growing literature associating physical discipline with later child aggression, spanking remains a typical experience for American children. The directionality of the associations between aggression and spanking and their continuity over time has received less attention. This study examined the transactional associations between spanking and externalizing behavior across the first decade of life, examining not only how spanking relates to externalizing behavior leading up to the important transition to adolescence, but whether higher levels of externalizing lead to more spanking over time as well. We use data from the Fragile families and child well-being (FFCW) study to examine maternal spanking and children’s behavior at ages 1, 3, 5, and 9 (N=1,874; 48 % girls). The FFCW is a longitudinal birth cohort study of children born between 1998 and 2000 in 20 medium to large US cities. A little over a quarter of this sample was spanked at age 1, and about half at age 3, 5, and 9. Estimates from a cross-lagged path model provided evidence of developmental continuity in both spanking and externalizing behavior, but results also highlighted important reciprocal processes taking hold early, with spanking influencing later externalizing behavior, which, in turn, predicted subsequent spanking. These bidirectional effects held across race/ethnicity and child’s gender. The findings highlight the lasting effects of early spanking, both in influencing early child’s behavior, and in affecting subsequent child’s externalizing and parental spanking in a reciprocal manner. These amplifying transactional processes underscore the importance of early intervention before patterns may cascade across domains in the transition to adolescence.

Keywords: Spanking, Externalizing, Aggression, Transactional, Cumulative risk

Introduction

Developmental theory provides strong reasons to believe that harsh treatment by parents may lead to aggressive behavior on the part of children through modeling (Bandura 1965), social information processing (Weiss et al. 1992), and setting in motion amplifying reciprocal cycles of coercion, or transactions between parent and child (Patterson 1982). Conversely, theory on child effects (Bell 1968; Thomas et al. 1963) provides strong reasons to believe that more challenging behavior by a child may lead to more harshness on the part of parents. As such, theory would suggest that there should be transactional or reciprocal links between the use of parental spanking and children’s externalizing behavior through the transition to adolescence.

The research literature on spanking over the past several decades has offered fairly consistent evidence that the use of physical punishment is associated with later externalizing behavior (Benjet and Kazdin 2003; Gershoff 2002; Lee et al. 2013; Mackenzie et al. 2012; Taylor et al. 2010), but important gaps in knowledge remain. Establishing the links between spanking and behavior is important because spanking remains a widely endorsed parenting tool in US families (Straus and Stewart 1999; Gershoff 2002), even among parents of infants in the first year of life (MacKenzie et al. 2011a, b, c). The establishment and amplification of these early family process patterns may be of particular concern for those focused on understanding the connection of earlier experiences of harsh parenting to outcomes during the transition into adolescence (Bender et al. 2007).

In particular, knowledge gaps remain in the areas of continuity in use of spanking over time, and the theorized reciprocal associations, or transactions, between spanking and children’s functioning across development (Berlin et al. 2009; Gershoff et al. 2012; Maguire-Jack et al. 2012). The transactional model provides a theoretical framework to understand reciprocal effects that play out across development, and conceptualizes the individual child and caregiver relationship as a dialectical process where development is a process of bidirectional change and mutual adaptation over time (MacKenzie and McDonough 2009). In a classic study, Patterson (1982) provides elegant evidence of these reciprocal processes unfolding through early amplifying cycles of coercion between parent and child resulting in increased aggressive behavior.

In an effort to increase our understanding of these bidirectional transactional processes, this article focuses on the following research questions: (1) whether spanking is related to subsequent externalizing behavior, when controls for earlier externalizing and other covariates are controlled, and whether these links are stronger at some ages; (2) whether externalizing behavior is related to subsequent spanking over time, when controls for earlier spanking and other covariates are controlled, and whether these links are stronger at some ages than others; (3) whether these associations are similar for different ethnic groups; and (4) whether these associations are similar across gender. We address these questions taking advantage of a rich longitudinal dataset that follows a diverse sample of children from birth to age 9 and employing a modeling approach that allows us to capture transactional processes (i.e., reciprocal effects of spanking on behavior as well as behavior on spanking) previously applied to spanking across a narrower age range (Berlin et al. 2009; Gershoff et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2013; Maguire-Jack et al. 2012) demonstrating evidence for amplifying reciprocal effects between parental spanking and children’s aggression across development.

In her seminal meta-analysis, Gershoff (2002) demonstrated an association between corporal punishment and 10 of the 11 children’s outcomes examined across childhood, with links to subsequent aggression showing up as the most common. However, much of that earlier literature relied on small samples and/or cross-sectional studies. More recent research has provided a stronger evidence base by using larger prospective longitudinal samples. In the present study, we build on and extend the work of two such studies (Gershoff et al. 2012; Maguire-Jack et al. 2012). Maguire-Jack et al. (2012), drawing on earlier waves of the same large cohort study we use here, analyzed the reciprocal links between spanking and children’s behavior from age 1 to age 5. Our work extends their analysis to age 9, which is important in determining whether the effects documented earlier in childhood persist or attenuate over time, particularly as the children enter middle childhood, the period examined by Gershoff et al. (2012) in their study of children age 5–8, and prepare for the important transition to adolescence. We provide the first evidence on reciprocal associations bridging across the entire first decade of life and also examine the continuity of the links over that period and the establishment of family process patterns for emerging adolescence.

In addition, we augment the analysis by examining differences by race/ethnicity. Some researchers have posited that spanking may have differential effects for African-American children, for whom spanking is more normative and/or used in the context of different parenting styles (see for e.g., Baumrind 1996; Deater-Deckard et al. 1996; Deater-Deckard and Dodge 1997; Deater-Deckard et al. 2005; Lansford et al. 2004). In her review, Gershoff (2002) was not able to test whether negative associations between spanking and children’s behavior were present regardless of the child’s race/ethnicity. Other studies have provided some evidence that the effects of spanking on children’s behavior may be less negative for African-American children. But since such studies often conflate SES and race, or control for only income or a small number of ecological risks, it is not clear to what extent these differences reflect differences across race/ethnicity versus SES (Horn et al. 2004). In line with this, other recent work with larger samples and national studies taking into account broad markers of the family ecology has not replicated this moderating role for race/ethnicity (see for e.g., Berlin et al. 2009; Gershoff et al. 2012; Grogan-Kaylor 2004; Lansford et al. 2011; MacKenzie et al. 2012; Mulvaney and Mebert 2007), suggesting that spanking has similar effects across racial/ethnic groups. We provide new evidence on this question by examining the extent to which race/ethnicity moderates the associations between spanking and externalizing behavior.

Since gender differences have been found in both the likelihood of experiencing early spanking (MacKenzie et al. 2011a, b, c) and in rates of externalizing behavioral problems (Leadbeater et al. 1999), we also felt it important to examine whether there are potential gender differences in the bidirectional associations between spanking and externalizing behavior over time. This is a question that has received less attention in the literature to date. Despite differences in rates of spanking and externalizing behavior, there are not strong theoretical grounds to suggest that those underlying pathways vary by gender.

Finally, we situate the transactional framework for exploring reciprocal effects between parent and child within an ecological model (Bronfenbrenner 1979). An ecological approach holds that, particularly earlier in childhood, exosystem and macrosystem stressors more distal to the family microsystem impact the parent and child, both directly and through the extent to which they impact the more proximal family interactions (MacKenzie et al. 2011a, b, c). To examine the parent–child microsystem processes across development, it is critical to include broad measures of the risk factors faced by the family over time. A cumulative risk index is an integrated and parsimonious way of modeling the array of risks that families face (Sameroff et al. 1987), where the focus is less on the individual contributions of individual risk factors and more on the overall cumulative effect of risk factors faced by the family. The cumulative risk approach has been demonstrated to have important effects on the likelihood of early harsh parenting (MacKenzie et al. 2011a, b, c) and the frequency of spanking (MacKenzie et al. 2012) and children’s externalizing behavior (MacKenzie et al. 2011a, b, c).

Current Study

The current study sought to address gaps in the literature and build on theory and prior empirical work in three key ways. First, applying a transactional model, we examine the reciprocal associations between spanking and children’s behavior over a longer span of time, from age 1 to age 9. In doing so, we expand on recent work (Gershoff et al. 2012; Lansford et al. 2011) demonstrating reciprocal effects between spanking and behavior in boys and girls from birth to age 5, and from age 6 to 9. Both of these recent studies on reciprocal effects highlight the need to examine transactional processes between maternal spanking and child’s behavior over a longer period of time—from infancy through middle childhood—and the inclusion of all four waves from the FFCW study allows us to extend this examination farther than has been possible to date. This allows us to examine how these coercive processes first develop, and also to examine developmental continuities and discontinuities from infancy through middle childhood across important childhood transitions to mobility, verbal communication, preschool, and school. We examine these developmental processes using a longitudinal dataset and within the context of a broad cumulative risk index of burdens and stressors (Sameroff et al. 1987). While we expect that there will be continuity in spanking and externalizing behavior over time, we hypothesize that the association between spanking and externalizing behavior will be transactional in nature, such that spanking would be associated with higher levels of externalizing at subsequent waves and higher externalizing behavior would in turn be associated with higher levels of downstream spanking. Second, we examine whether these reciprocal associations differ by race/ethnicity. Drawing on recent work, we hypothesize that race/ethnicity will not moderate the cross-lag associations between spanking and externalizing behavior. Third, we examine potential gender differences, which have been relatively under-studied. Despite differences in rates of spanking and externalizing behavior by gender, the literature provides little theoretical guidance for expectations around potential gender differences in the underlying developmental pathways. The current analytic approach provides the opportunity for an exploratory examination of whether the transactional pathways between spanking and externalizing behavior vary by gender.

Method

Data

We use data from the Fragile Families and Child Well-Being Study (FFCW; Reichman et al. 2001). FFCW is a longitudinal birth cohort study of children born between 1998 and 2000 in 20 medium to large US cities. Baseline in-person interviews with both the mother and father took place in the hospital shortly after the focal child was born. Follow-up interviews were conducted by telephone when the focal child was approximately 1 year-of-age, again when the child was approximately 3 years-of-age, and also when the child was approximately 5 and 9 years-of-age. In addition, in-home interviews and visits were held with the mothers and children at age 3 and 5 to supplement the phone interviews.

The study’s analytic sample was limited to families in which there were valid responses to the key variables from these interviews including the risk index, and the outcome variables of spanking and externalizing behavior. The resultant sample included 1,874 families and descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1. In results not shown, but available on request, we compared the analytic sample with the total FFCWS sample (N=4,079) to determine the extent to which our analytic sample differed from the total sample. We first compared the samples on demographics (child’s gender, race/ethnicity proportions, percent first born, and maternal age at birth) and found no significant differences from the total FFCWS sample. We next compared the analytic sample to the total FFCWS sample on the 16 risk factors that comprise our cumulative risk index and found them to differ on only two of those risk factors. The mothers in the analytic sample were less likely to have had late starting or no prenatal care (17.6 vs. 20.1 % in the full FFCWS sample; z = 2.27, p < .05, two-tailed), and they were also less likely to be foreign born (10.7 vs. 13.3 % in the full FFCWS sample; z = 2.49, p < .05, two-tailed). Based on this comparison, the families making up the analytic sample appear to differ from the total FFCWS sample in only some limited respects, and those two variables are controlled for in our SEM analysis as part of the cumulative risk index. Nevertheless, as shown in the descriptive statistics below, they remain a fairly disadvantaged urban sample.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for analytic sample

| Sample (N = 1,874)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 1 | Age 3 | Age 5 | Age 9 | |

| % mothers report spanking more than twice in past month | 6.7 % | 12.7 % | 5.5 % | 4.1 % |

| % mothers report spanking once or twice in past month | 21.6 | 44.0 | 47.1 | 44.5 |

| % mothers report not spanking child in past month | 71.7 | 43.3 | 47.4 | 51.4 |

| % Girls | 48 % | |||

| Age of child at age 1 assessment [months; M (SD)] | 14.9 (3.5) | |||

| Age of child at age 3 assessment [months; M (SD)] | 35.9 (1.9) | |||

| Age of child at age 5 assessment [months; M (SD)] | 60.7 (2.2) | |||

| Age of child at age 9 assessment [months; M (SD)] | 111.3 (3.6) | |||

| % First born | 38.8 % | |||

| Average age of mother at birth [years; M (SD)] | 25.1 (6.0) | |||

| % European-American | 23.6 % | |||

| %African-American | 51.6 % | |||

| % Latino/Hispanic-American | 21.8 % | |||

| % Other (Asian Pacific Islander, American Indian) | 3.0 % | |||

| Cumulative Risk Index Variables | ||||

| Cumulative Risk Index Total Score [M (SD)] | 4.8 (2.8) | |||

| Risk factor 1: late or no prenatal care (% with risk) | 17.6 % | |||

| Risk factor 2: born low birth weight (<2,500 g) | 9.7 % | |||

| Risk factor 3: mother not born in US | 10.7 % | |||

| Risk factor 4: mother’s WAIS-R scorea | 16.0 % | |||

| Risk factor 5: bio parents not living together | 43.0 % | |||

| Risk factor 6: mother has less than HS diploma/GED | 32.8 % | |||

| Risk factor 7: mother’s overall health < very good | 36.7 % | |||

| Risk factor 8: mother’s potential depression or anxiety | 17.3 % | |||

| Risk factor 9: Mother smoked, drank, or used drugs | 30.4 % | |||

| Risk factor 10: 3 or more children in home | 16.0 % | |||

| Risk factor 11: mother used TANF or food stamps | 41.4 % | |||

| Risk factor 12: household at below poverty level | 44.1 % | |||

| Risk factor 13: Level of economic hardshipa | 17.0 % | |||

| Risk factor 14: Level of parental stressa | 15.4 % | |||

| Risk factor 15: any reported IPV behavior from father | 17.8 % | |||

| Risk factor 16: father has history of incarceration | 31.2 % | |||

Counted as a risk if the score was more than 1 standard deviation worse than mean

Outcome Variables

Spanking

At the first three waves, mothers were asked “… (i)n the past month, have you spanked (CHILD) because (HE/SHE) was misbehaving or acting up?.” Mothers who reported spanking in the past month were then asked about their frequency of spanking using 4 categories (every day or nearly every day; a few times a week; a few times this past month; only once or twice). We used these questions to divide mothers into three groups: those who did not spank at all at that age (coded 0), those who spanked once or twice (low frequency, coded 1), and those who spanked more than twice in the past month (high frequency, coded 2).

At year 9, these items were not available. However, the spanking item from the Conflicts Tactics Scale from this wave was available for this analysis. The question asks whether the parent spanked the child with hand on bare bottom in the past year and if so, how often, with 8 response categories (this has never happened; yes, but not in the past year; once; twice; 3–5 times; 6–10 times; 11–20 times; more than 20 times). The two responses representing the highest frequency of spanking (11–20 times, or more than 20 times in the past year) were coded as high frequency spanking (2), while any other affirmative response was coded as low frequency spanking (1), and no spanking in the past year was coded 0.

Child’s Externalizing Behavior

Mothers reported on children’s externalizing behavior at 3, 5, and 9 years-of-age using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). The CBCL Externalizing behavior score draws upon items asked of the mother across the in-home and phone interviews. These items comprise the aggression and rule-breaking subscales available in the CBCL, with responses ranging from Not True (0), to Sometimes True (1), and Often True (2). At age 1, there is no equivalent measure of externalizing behavior, so we substitute a maternal reported child’s temperament measure looking at negative emotionality. The emotional temperament measure used three summed items rated on a 5 point scale (not at all to very much): whether the child often fusses/cries, is easily upset, and reacts strongly when upset.

Factor Included in the Cumulative Risk Index

In order to focus on the directionality of influence between spanking and children’s externalizing behavior over time, it is essential to account for the risk context in which families are situated. We include a broad set of risks, drawing on the broad data from the FFCW dataset, in an attempt to capture as much information as possible about family factors that might be correlated with both spanking and child’s externalizing behavior. A total of 16 binary risk factors defined below were summed to create a cumulative risk index at age 1 and percentages of presence of each risk factor are show in Table 1.

Prenatal Care

Families were coded as a 1 if the mother indicated she received no, or late starting (after first trimester) prenatal care. This variable may indicate mothers’ health behaviors during pregnancy.

Low Birth-Weight

Families were coded as a 1 for presence of the risk factor if mother reported the child had a birth weight below 2,500 g. This variable also may indicate mothers’ health behaviors during pregnancy.

Maternal Nativity

Families were coded as a 1 if the mother reported being born outside of the United States. This is not to suggest that being foreign-born is inherently a risk factor in and of itself, although earlier work with this dataset found maternal immigration status to be significantly associated with child’s externalizing for children through age 5 (MacKenzie et al. 2012), and, perhaps owing to reduced social support networks and access to services, that foreign-born mothers were more vulnerable to the influence of intimate partner violence and stress on their harsh parenting (Taylor et al. 2009). Thus, we conceive of this as important to include as a proxy for the possibility of acculturation stress, discrimination, reduced family and social support networks and lack of educational and employment opportunities or access to services that can accompany the immigration process.

Maternal Cognitive Ability

The family received a score of 1 to indicate the presence of the risk condition if the maternal score on the modified version of the Similarities subtest of the Weschler Adult Intelligence Subscale-Revised (WAIS-R) was 1 Standard Deviation or more below the mean. This variable therefore captures mothers who have very low cognitive ability.

Marital Status

A score of 1 for this risk condition was indicated if the two biological parents were not cohabitating or married at age 1. A mother who is not living with the biological father at age 1 may have access to fewer resources and less social support.

Maternal Education

The risk condition was indicated with a score of 1 if the mother reported having less than a high school diploma or GED. Thus, this variable indicates mothers who had extremely low levels of education.

Maternal Health

The seventh risk factor was indicated if the mother reported her overall health to be less than very good or excellent, the two top responses on a five-point scale asking about general health. This variable captures mothers who have only good, fair, or poor health.

Maternal Depression or Anxiety

The risk condition was coded as a 1 if the mother reported symptoms that indicate potential Depression or Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CIDI-SF; Nelson et al. 1998). The CIDI-SF depression measure has been widely used in prior research and can be coded as a dichotomous measure of major depression “caseness,” categorizing a respondent as potentially suffering from depression if she scores 3 or higher. Maternal symptoms of anxiety were measured using the CIDI-SF for general anxiety disorder (GAD). The stem questions for GAD considered whether the mother experienced a period lasting a month or more where she felt worried or anxious most of the time and, if so, what was the longest period. The stem conditions were coupled with affirmative responses on at least three physiological symptoms result in the respondent being coded with potential GAD. We coded the mother as 1 if she was identified as potentially suffering from either depression or anxiety.

Maternal Risk Behaviors

The ninth risk factor captured any smoking, taking any drugs or moderate to heavy alcohol use at the year 1 interview. 30.4 % of the mothers reported engaging in at least one of these risk behaviors at year 1 and received a score of 1.

Family Size

The family received a score of 1 if the mother reported 3 or more children under 18 in the home at the age 1 interview. A large number of other children in the home has been identified as a risk factor for both harsh parenting (MacKenzie et al. 2011a, b, c) and child’s externalizing behavior (MacKenzie et al. 2011a, b, c).

Social Assistance

The family received a score of 1 if the family received Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) or Food Stamps in the past 12 months as the age 1 interview. This variable thus identifies families who had low incomes and had to rely on public assistance.

Income to Needs

The family received a score of 1 to indicate the risk condition for this binary measure of poverty based on household income to needs ratio being at or below poverty level for family size at year 1. This variable provides another indication of low income.

Economic Hardship

The risk factor was indicated for families more than 1 standard deviation from the mean at year 1. The hardship score is based on the mother’s responses to 12 Yes (1)/No (0) questions on economic conditions faced in the past year, e.g., trouble paying utilities, not pay rent, borrow money from friends/family.

Maternal Parenting Stress

The fourteenth risk factor was a measure of maternal parenting stress at age 1, based on questions about how difficult the mother found being a parent. The risk factor is indicated with a score of 1 for all families scoring more than 1 standard deviation from the mean toward higher stress at age 1.

Intimate Partner Violence

The family received a score of 1 if the mother reported any intimate partner violence at the age 1 interview.

Paternal Incarceration

The family received a score of 1 if the mother or father reported any history of paternal incarceration.

Other Covariates

In addition to the cumulative risk index, which summarizes the child and family risk factors that might influence both spanking and externalizing, we also included a control for child’s gender, to account for gender differences in externalizing and spanking. The models also included controls for city fixed effects (i.e., a dummy variable for each of the cities in the dataset) to control for any differences in spanking or children’s behavior by city.

Analysis

We use the data from FFCW to estimate a cross-lagged path analysis of children’s externalizing behaviors and maternal spanking across all four waves. All analyses were carried out using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp 2011). The cross-lag structural equation model estimates the reciprocal associations between maternal spanking frequency and child’s externalizing behavior at age 1, 3, 5, and 9 years, while also including an additional path from early spanking at age 1 to age 9 externalizing behavior to account for the importance of early onset spanking that has been demonstrated in the literature. The model controls for the influence of child’s gender, city, and the cumulative ecological risk index score (as described above) as three separate variables with direct paths to both child’s behavior and parental spanking at each wave.

Results

As shown in Table 1, maternal reports of at least some use of spanking in the past month was common across all waves from infancy through age 9. At year 1, 28 % of children were spanked by their mother, with 7 % spanked two or more times a week. This rose to 57 % by year 3, with 13 % in the high frequency group during the preschool period. At the transition to school at age 5 spanking remained fairly stable at 53 %, with a dip to 6 % at high frequency. Rates even remained relatively stable out to age 9 with 49 % spanking, with 4 % of those at high frequency as the children transitioned into middle childhood.

Cross-Lag Models of Transactional Processes

We tested a cross-lagged path model including maternal spanking frequency and child’s behavior for the full sample at the age 1, 3, 5 and 9 year-old waves (n=1,874). As mentioned, the model controlled for the effects of child’s gender, city of residence, and cumulative risk score on spanking and child’s behavior at each wave. The model looked at continuity in spanking and child’s behavior as well as concurrent covariation between spanking and behavior at each wave. We also examine the cross-lag effects of children’s behavior on subsequent spanking, and spanking on subsequent behavior by children, accounting for the earlier spanking or externalizing, in order to examine transactional changes over time.

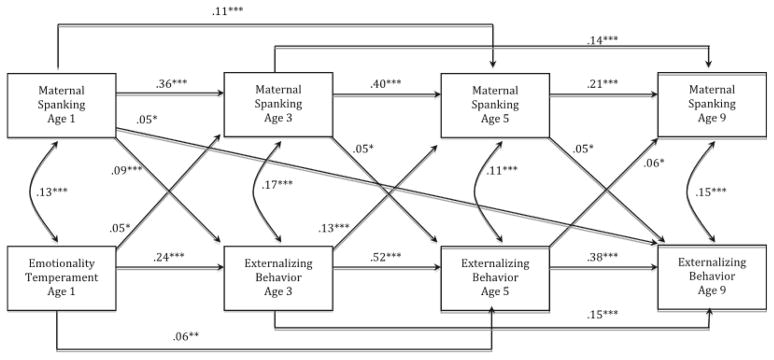

The model (Fig. 1) provided a good fit for the data with a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.031 (90 % Confidence Interval = 0.015–0.048, pClose test p = 0.97, thus RMSEA is not [than 0.05), comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.996, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.969, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.009, and x2 (7) = 19.67, p = 0.006. Figure 1 shows the standardized path coefficients, which highlight the strong continuity in both child’s behavior and spanking frequency across the 4 waves. (Path coefficients for gender, city, and cumulative risk are included in the model predicting children’s behavior and parental spanking at each age, but are not shown in Fig. 1.) The model also shows the significant concurrent covariation between spanking and children’s behavior at each wave. Each of the cross-lag paths predicting later spanking or children’s behavior was significant taking into account the developmental continuity in that behavior from the earlier waves. For the cross-lag from age 5 to age 9 there was no significant difference in the magnitude of the coefficients for the association of child’s behavior with later spanking and for the association of spanking with later child’s behavior (z = .166, p = .43), and from age 1 to age 3 there was a trend toward a significant difference (z =− 1.52, p = .065). From age 3 to age 5, however, while both paths were significant in the model, the association of child’s behavior with later spanking was larger than the association of spanking with later externalizing (z = 2.79, p = .003). The final model fit highlights the potential importance of early spanking during infancy on putting these transactional processes in motion.

Fig. 1.

Results from a cross-lagged SEM path model from age 1 through 9 for maternal spanking and child behavior. Values shown are standardized coefficients and covariance is indicated by curved line with double-headed arrow. Model controls for influence of child gender, city of residence, and a cumulative risk index score on spanking and child behavior at each wave (n = 1,874; *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001)

Importantly, these spanking effects are present even after controlling for the effects of gender, city of residence, and the 16-factor cumulative risk index on both spanking and child’s behavior across all four waves. In the full model the cumulative risk index significantly predicted child’s temperament at year 1 (Standardized b = 0.17, p < .001), and externalizing behavior at year 3 (Standardized b = 0.19, p < .001), year 5 (Standardized b = 0.12, p < .001), and year 9 (Standardized b = 0.05, p < .01). The cumulative risk index was also significantly associated with initiation of early spanking at year 1 (Standardized b = 0.06, p < .01), although it did not significantly predict spanking in the full model for years 3 through 9, once its influence on year 1 spanking is taken into account, likely in part as a result of the high degree of developmental continuity in spanking over time and the mediated effect of externalizing on later spanking.

Next, we tested whether the model would provide a good fit across three racial/ethnic groups comparing European-American, African-American and Latino/Hispanic-American (we did not include the Other race/ethnicity category in this group analysis due to small sample size). To do this we estimated the same path model to compare across racial/ethnic groups (RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.994; TLI = 0.959; SRMR = 0.014; x2 (28) = 37.28, p = 0.02). The model offered good group-level fit for all four race/ethnic groups (European-American, SRMR = 0.02; African-American, SRMR = 0.01; and Latino/Hispanic-American, SRMR = 0.02), with the pattern of findings by group being largely the same as for the full sample. Test for group invariance of parameters through Wald Tests indicated that only 2 of the 21 parameters in the model (both dealing with continuity in spanking) had some differences across race/ethnic groups and we followed this with additional analysis not shown but available on request to examine where differences in coefficients existed across racial/ethnic groups correcting for multiple comparisons (Spanking age 3 → Spanking age 5, x2 (3) = 17.32, p < 0.001, with white mothers showing stronger continuity in spanking from age 3 to age 5 than African American and Hispanic mothers; and Spanking age 5 → Spanking age 9, x2 (3) = 10.88, p < 0.01, with Hispanic mothers showing stronger continuity in spanking from age 5 to age 9 than African American mothers. Importantly, none of these invariant parameters across racial/ethnic groups involved the focal cross-lag paths for associations between spanking and later behavior, or behavior and later spanking across the race/ethnic groups.

Finally, we tested whether the model would provide a good fit across genders. To do this, we estimated the same path model (without the gender control entered) to compare across gender groups (RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.993; TLI = 0.957; SRMR = 0.014; x2 (14) = 34.84, p = 0.002). The model offered good group-level fit for both boys and girls (boys, SRMR = 0.016; girls, SRMR = 0.010), with a similar pattern of findings for both genders to the full sample. Test for group invariance of parameters through Wald Tests indicated that only 2 of the 21 parameters in the model (both dealing with continuity in children’s behavior) exhibited some differences across gender groups (Temperament age 1 → age 5 externalizing, x2 (1) = 8.34, p < 0.01, with girls showing a stronger association between temperament and age 5 externalizing; and externalizing age 3 → externalizing age 9, x2 (1) = 4.52, p < 0.05, with boys exhibiting stronger continuity from age 3 to age 9 externalizing behavior). Again, neither of these invariant parameters involved the focal cross-lag paths of interest for associations between spanking and later behavior, or behavior and later spanking across gender.

Discussion

Increasing our understanding of complex transactional processes starting in early childhood and extending into the adolescent transition is an important component of efforts to better understand adolescent developmental trajectories of aggression. One area where our understanding of the etiology of these trajectories has been limited is in elucidating the bi-directionality of effects between parental use of physical discipline and children’s aggression across development. Theory and the emerging empirical literature on developmental cascades in adolescence (Masten and Cicchetti 2010), where we see evidence of cross-domain influences in functioning cascading beyond aggression (Bornstein et al. 2010; McClain et al. 2010), underscores why understanding early parenting contributions to aggression may be important not just for aggression pathways alone, but also for other domains of development. This is particularly true, if aggressive behavior by emerging adolescents may be in turn shaping behavior of other interaction partners including parents, teachers, and peers. The current study thus sought to examine the reciprocal associations between parental spanking and children’s externalizing behavior across the first decade of life, with a special focus on whether those developmental processes differ across gender and race/ethnicity.

The results of this study indicate that there are reciprocal associations between spanking and externalizing behavior and that these processes extend across the first decade. These links between spanking and later externalizing are particularly important given that spanking is a typical experience for US children in urban communities, with about a quarter of children spanked at age 1 and about half at age 3, 5, and 9.

Our analysis of the bidirectional links between spanking and child’s externalizing behavior is distinctive in the range of ages examined, and in the diversity of the sample and breadth of control variables available for analysis in our cumulative risk approach. We take a transactional perspective (Sameroff and MacKenzie 2003) in conceptualizing how maternal spanking and children’s externalizing behavior reciprocally influence each other across development (Berlin et al. 2009; Gershoff et al. 2012; Lansford et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2013; Maguire-Jack et al. 2012). We also recognize that the accumulation of stressors and risks from across the ecology have the capacity to affect more proximal family relationship processes including harsh parenting (MacKenzie et al. 2011a, b, c, 2012). We further recognize that these risks are also likely to influence children’s behavior in pathways not mediated by parental discipline practices, underscoring the importance of controlling for the influence of cumulative risk on both spanking frequency and child’s behavior at each wave.

Overall, the results from our cross-lagged path analysis from age 1 through age 9 are consistent with the literature pointing toward an association between spanking and later externalizing behavior (Berlin et al. 2009; Gershoff 2002; Gershoff et al. 2012; Lansford et al. 2011; Maguire-Jack et al. 2012; Taylor et al. 2010). We replicate these effects even after being able to put in place controls for gender, city of residence, and a broad cumulative ecological risk index. Despite evidence of strong continuity in both spanking and children’s externalizing over time, and concurrent covariation at each wave, we also find evidence of bidirectional effects between spanking and behavior over time. This finding of reciprocal chains of influence is in keeping with the earlier studies that have examined transactions over a narrower range of years in early childhood (Berlin et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2013; Maguire-Jack et al. 2012) and later in middle childhood and adolescence (Gershoff et al. 2012; Lansford et al. 2011). The current analysis bridges these transitions starting in infancy and extending through important transitions into mobility, verbal communication, school and across the transition into middle childhood.

Our results indicate that maternal spanking predicts increases in later child’s externalizing behavior at each wave, taking into account earlier child’s behavior. And, children’s externalizing predicts increases in maternal spanking, taking into account earlier spanking. These apparent amplifying transactional cycles across development (MacKenzie and McDonough 2009) provide further evidence for contingent coercive pathways elucidated by Patterson (1982). Analyzing children through age 5, Maguire-Jack et al. (2012) found that spanking at age 3 had an effect on child’s behavior at age 5. We find similar results to age 5 but add to this the finding that spanking at age 5 continues to affect child’s behavior at age 9. In addition, we find that early spanking in the first year carries effects extending through age 9, and that early externalizing also elicits later increased spanking.

The finding that these reciprocal processes do not differ across racial/ethnic groups is consistent with what we hypothesized and builds on some recent work (Berlin et al. 2009; Gershoff et al. 2012; Grogan-Kaylor 2004; MacKenzie et al. 2012; Mulvaney and Mebert 2007) that has not replicated earlier findings in small or non-representative datasets that the effects of spanking on children’s behavior may be less negative for African-American children. This is an important finding because beliefs about normativeness and effects within racial/ethnic communities can be an important predictor of the decision to spank (MacKenzie et al. 2011a, b, c). The finding that these cross-lag processes do not differ by gender is more novel, as few prior studies have examined differences across boys and girls. This too is an important finding because, while levels of early spanking and externalizing behavior may vary across gender (MacKenzie et al. 2011a, b, c) and continuity in spanking may be stronger for boys through middle childhood into adolescence (Huesmann et al. 1984), it appears the mechanisms of association over time do not differ across gender.

Extending earlier work by Maguire-Jack et al. (2012) in their recent analysis of children earlier in development, and the work by Gershoff and colleagues (Gershoff et al. 2012) from kindergarten through third grade, our study offers several new findings. The longer period of development examined allowed us to highlight the importance of early spanking in the first year to children’s behavioral outcomes even taking into account later spanking and the effects of continuity in spanking. Sameroff and MacKenzie (2003), in their review of the transactional model of child development, suggested that in the absence of longitudinal data spanning across developmental transitions that longer-term mechanisms can be pieced together across different datasets. But the current study has offered important data on these bidirectional mechanisms through following one sample of children across the full first decade of life.

Our study does have some limitations. One limitation is that, apart from the year 9 wave when spanking was specifically defined as slapping with an open hand on the child’s buttocks, parents were left to apply their own definition to the question of whether they “spank” at earlier waves. This allows for the potential for some parents to include more severe behaviors such as hitting with a belt for example under their definition of “spanking” while others might be reporting less severe behaviors. This limitation is common to all studies that rely on parental responses to a general question about spanking. Our examination is strengthened, however, by having a measure of frequency, although in order to have similar ranges of spanking across the different waves of data collection when the question was asked slightly differently we had to reduce the frequency data into categories of no spanking, low spanking and high spanking. We also had to rely on maternal report of child’s behavior in the current data, which raises the possibility that a negative perception of the child has the potential to influence both spanking behavior and maternal ratings of a child’s externalizing behavior. We feel that the potential for such an effect is limited by the fact the CBCL pulls for parents to report on the amounts of very specific behaviors, and by the correspondence of our results with the findings of Gershoff et al. (2012) who used teacher report of children’s behavioral problems. Finally, in common with most of the literature, we focus on children’s behavioral outcomes and do not examine the effects of spanking on other aspects of child development. Recent work has highlighted possible effects of parental spanking on children’s cognitive development (MacKenzie et al. 2013) and this too is an important direction for future research.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight the lasting effects of early spanking, both in influencing early behavior and in affecting children’s behavior and subsequent parenting across childhood into the adolescent transition. These findings, particularly the role of spanking in the first year, point to the importance of intervening early when new parents may be more open to supports and before family processes become routinized heading into the transition to adolescence. The data show stable and amplifying transactional processes playing out between physical discipline and children’s aggression once they get set in motion, which may be easier to prevent than to alter. Increasing our understanding of these early stable family dynamics will improve our capacity to model the transition to the adolescent period and the potential for cascading effects spilling over from aggression into other domains of youth functioning and psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Biographies

Michael J. MacKenzie is an Associate Professor at the Columbia University School of Social Work. He received a joint doctorate in Developmental Psychology and Social Work from the University of Michigan. His major research examines the etiology and sequelae of harsh parenting and child maltreatment and alternative models of care for children in need of out-of-home placement.

Eric Nicklas is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Columbia University School of Social Work, where he received his doctorate in Social Work. In addition to work in the child welfare system, his research has focused on harsh parenting and neglect and child development.

Jeanne Brooks-Gunn is the Virginia and Leonard Marx Professor of Child Development and Education, Teachers College and College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University. She received her doctorate in Human Learning and Development at the University of Pennsylvania. Her work focuses on child and family policy programs and adolescent transitions.

Jane Waldfogel is the Compton Foundation Centennial Professor of Social Work for the Prevention of Children’s and Youth Problems. She received her doctorate in Public Policy at Harvard University. Her research focuses on the impact of public policies on child and family well-being, poverty, inequality and social mobility.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author contributions

MJM conceived the study, completed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. EN participated in the design of the study, participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and edited the manuscript. JB-G participated in the design of the study and interpretation of results and helped to draft the manuscript. JW participated in the design of the study and the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Michael J. MacKenzie, Email: mm3038@columbia.edu, School of Social Work, Columbia University, 1255 Amsterdam Ave., New York, NY 10027, USA

Eric Nicklas, School of Social Work, Columbia University, 1255 Amsterdam Ave., New York, NY 10027, USA.

Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Teacher’s College and the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Jane Waldfogel, School of Social Work, Columbia University, 1255 Amsterdam Ave., New York, NY 10027, USA.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Influence of models’ reinforcement contingencies on the acquisition of imitative responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1965;1:589–595. doi: 10.1037/h0022070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. A blanket injunction against disciplinary use of spanking is not warranted by the data. Pediatrics. 1996;98:828–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review. 1968;75:81–95. doi: 10.1037/h0025583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender HL, Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Antonishak J, Moore CM, Kelly HO, et al. Use of harsh physical discipline and developmental outcomes in adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:227–242. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Kazdin AE. Spanking children: The controversies, findings, and new directions. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:197–224. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Malone PS, Ayoub CA, Ispa J, Fine M, Brooks-Gunn J, et al. Correlates and consequences of spanking and verbal punishment for low income White, African American, and Mexican American toddlers. Child Development. 2009;80:1403–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn CS, Haynes OM. Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:717–735. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JA, Petit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Sorbring E. Cultural difference in the effects of physical punishment. In: Rutter M, Tienda M, editors. Ethnicity and causal mechanisms. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff E. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:530–579. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Lansford JE, Sexton HR, David-Kean P, Sameroff AJ. Longitudinal links between spanking and children’s externalizing behaviors in a national sample of white, black, Hispanic, and Asian American families. Child Development. 2012;83:838–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan-Kaylor A. The effect of corporal punishment on antisocial behavior in children. Social Work Research. 2004;28:153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Horn IB, Cheng TL, Joseph J. Discipline in the African American community: The impact of socioeconomic status on beliefs and practices. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1236–1241. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Eron LD, Lefkowitz MM, Walder LO. Stability of aggression over time and generations. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:1120–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Criss MM, Laird RD, Shaw DE, Pettit GS, Bates JE, et al. Reciprocal relations between parents’ physical discipline and children’s externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:225–238. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Ethnic differences in the link between physical discipline and later adolescent externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:801–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Kuperminc GP, Blatt SJ, Hertzog CA. Multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(5):1268–1282. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Altschul I, Gershoff ET. Does warmth moderate longitudinal associations between maternal spanking and child aggression in early childhood? Developmental Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0031630. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Kotch JB, Lee LI. Toward a cumulative ecological risk model for the etiology of child maltreatment. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011a;33:1638–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Kotch JB, Lee LC, Augsberger A, Hutto N. The cumulative ecological risk model of child maltreatment and child behavioral outcomes: Reconceptualizing reported maltreatment as risk factor. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011b;33:2392–2398. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, McDonough SC. Transactions between perception and reality: Maternal beliefs and infant regulatory behavior. In: Sameroff AJ, editor. The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. Washington: APA Books; 2009. pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Brooks-Gunn J, Waldfogel J. Who spanks infants and toddlers? Evidence from the fragile families and child well-being study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011c;33:1364–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Waldfogel J, Brooks-Gunn J. Corporal punishment and child behavioral and cognitive outcomes through 5 years of age: Evidence from a contemporary urban birth cohort study. Infant and Child Development. 2012;21(1):3–33. doi: 10.1002/icd.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Waldfogel J, Brooks-Gunn J. Spanking and child development across the first decade of life. Pediatrics. 2013 doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K, Gromoske AN, Berger LM. Spanking and child development during the first 5 years of life. Child Development. 2012;83:1960–1977. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClain DB, Wolchik SA, Winslow E, Tein JY, Sandler IN, Millsap RE. Developmental cascade effects of the New Beginnings Program on adolescent adaptation outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:771–784. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney MK, Mebert CJ. Parental corporal punishment predicts behavior problems in early childhood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:389–395. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CB, Kessler RC, Mroczek D. Scoring the World Health Organization’s composite international diagnostic interview short form (CIDI-SF; v 1.0 Nov 98) Epidemiology, Classification and Assessment Group, World Health Organization, Geneva; Switzerland: 1998. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family interactions. Eugene, OR: Castalia Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, McLanahan SS. Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23:303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, MacKenzie MJ. Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:613–640. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Zax M, Barocas R. Early indicators of developmental risk: The Rochester Longitudinal Study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13:383–393. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Sofware: Release 12.0. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M, Stewart JH. Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1999;2:55–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1021891529770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CA, Guterman NB, Lee SJ, Rathouz PJ. Intimate partner violence, maternal stress, nativity, and risk for maternal maltreatment of young children. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:175–183. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CA, Manganello JA, Lee SJ, Rice JC. Mothers’ spanking of 3-year-old children and subsequent risk of children’s aggressive behavior. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1057–1065. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Chess S, Birch HG, Hertzig ME, Korn S. Behavioral individuality in early childhood. New York: New York University Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Some consequences of early harsh discipline: Child aggression and a maladaptive social information processing style. Child Development. 1992;63:1321–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]