Abstract

Purpose: Small pulmonary lesions that include ground-glass attenuation have been increasingly discovered because of progressive imaging diagnostic technologies. Despite the detection of such small lesions, sometimes it is quite difficult to localize them because of their size or considerable depth from the visceral pleura. In the present study, we examined the usefulness of computed tomography-guided lipiodol marking for thoracoscopic resection of impalpable pulmonary nodules.

Methods: Fifty-six patients with an undiagnosed peripheral lesion(s) of the lung who had undergone preoperative computed tomography-guided lipiodol marking followed by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery were studied.

Results: All of the nodules were successfully marked by computed tomography-guided lipiodol marking, and all except for one case were localized by means of intraoperative fluoroscopy as clear spots. With regard to complications, pneumothorax occurred in 21 patients (37.5%), and only one patient required transient drainage. Although hemorrhaging in the lung parenchyma and hemosputum occurred in nine patients (16.1%) and one patient (1.8%), respectively, no patients were in serious condition. No intra- or postoperative mortality or morbidity was observed.

Conclusion: Preoperative computed tomography-guided lipiodol marking of small or impalpable pulmonary nodules is a safe and useful procedure for thoracoscopic resection of the lung.

Keywords: VATS, small pulmonary nodule, lipiodol marking, horizontal setting

Introduction

Because of the latest advanced technologies in radiological diagnosis, small lesions in the lung are often subject to surgery. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) detection of small, growing lung nodules, including lesions with ground-glass attenuation (GGA), raises the possibility of early lung cancer and/or metastatic lung tumor, which causes anxiety in patients and referring clinicians. However, in some cases, it is very difficult to palpate and identify the lesions during video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) because lesions are faint with a GGA appearance or have a thin wall with a cavity. In addition, nodules lying relatively deep in the lung parenchyma are difficult to palpate during VATS. In 1999, Suzuki et al. reported that of patients with indeterminate lesions who underwent VATS, despite preoperative transthoracic needle biopsy and/or transbronchial biopsy, 46% of patients required a change of treatment to thoracotomy because of the failure to localize nodules, indicating that preoperative marking for a small indeterminate pulmonary nodules should be considered when the distance to the nearest pleural surface is >5 mm in the case of lung nodules ≤10 mm in size.1) Since then, several techniques have been developed to localize pulmonary nodules, although the majority of thoracic surgeons adopt the finger palpation technique. Indeed, in most cases, it seems possible to palpate such lesions if the surgeon directly palpates by hand; however, the conventional open thoracotomy and also mini-thoracotomy are clearly inferior to pure VATS in terms of operativeinvasiveness. Preoperative localization appears to resolve the former issue, and a number of small nodule localization techniques aimed at guiding VATS resection have been developed.2–20) Although there are many techniques for preoperative localization of pulmonary lesions, CT-guided lipiodol marking may be the most appropriate method for impalpable pulmonary lesions for several reasons. We describe the procedure and assess the usefulness of the CT-guided lipiodol marking technique based on our experiences.

Patients and Methods

From November 2007 to December 2014, 56 patients (27 male and 29 female) with an undiagnosed pulmonary lesion(s) that included GGA underwent CT-guided lipiodol marking followed by VATS in our institute. The mean patient age was 62.9 years ± 12.5 (standard deviation) (age range, 34–87 years). Lesions that seem difficult to identify by intraoperative palpation were included in the study. Candidates for lipiodol marking are lesions ≤10 mm in diameter and/or with a distance to the nearest pleural surface of >10 mm that are also localized in the outer third of thelung parenchyma. Additionally, lesions that formed thin walls within a marked cavitywere included. Written, informed consent concerning CT-guided lipiodol marking and the operation was obtained from every patient and/or his/her legal representative after they had discussed the risks and benefits of the procedure with surgeons. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gunma University Hospital.

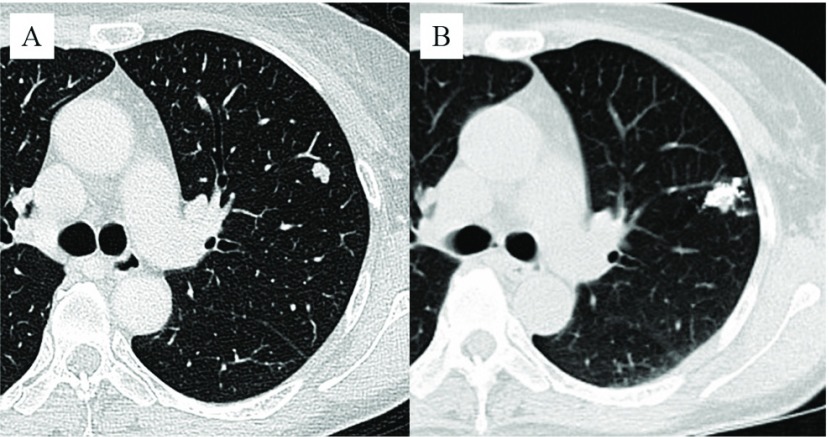

The procedure used for marking was as follows. Within a few days (usually one day) before surgery, CT-guided lipiodol marking was performed on the patient in the CT room. A scaled paper with metal wires was placed firmly on the patient, and a CT scan was performed. After the site for marker injection was marked on the skin, the skin was sterilized around the puncture site, and then local anesthesia was administered to the thoracic wall. A 23-gauge needle was introduced through the skin to the perilesional pulmonary parenchyma. The syringe was withdrawn to confirm that no blood or air had flowed backward, and then 0.2 mL to 0.6 mL of lipiodol (Lipiodol UltraFluid; Laboratory Guerbet; Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France) was carefully injected very closely adjacent to the lesionin a single shot (Fig. 1A and B).

Fig. 1.

Small nodular lesion, 8 mm in size, in the left upper lobe (A). The lesion is marked with 0.4 mL of lipiodol.

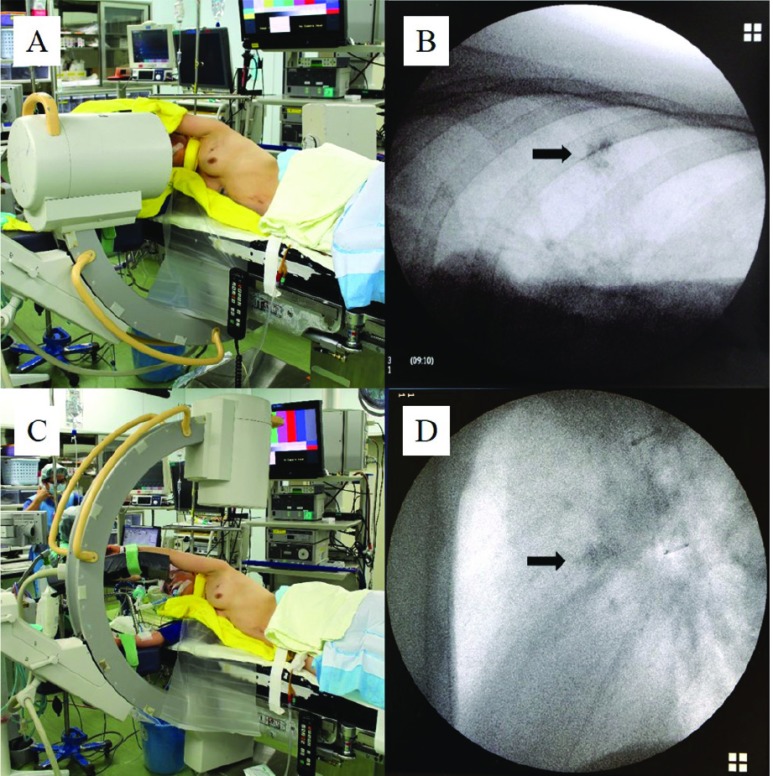

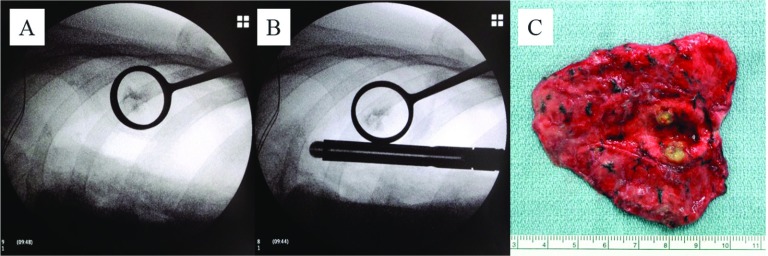

Video-assisted thoracoscopic resection of the lesion was performed under general anesthesia using single lung ventilation via a double-lumen endobronchial tube. The patient was placed in the lateral decubitus position with the involved lung superior and collapsed. Thereafter, a C-arm-shaped fluoroscopy unit was placed horizontally in an adequate position (Fig. 2A). The operative procedures usually involved making twothoracic ports of 12 mm each, one for the thoracoscope and the other for the endoscopic stapler device, and a 5.5-mm thoracic port for the lung forceps. As necessary, an additional 2- to 3-cm skin incision was made with appropriate intercostal space to grasp the lesion by a ring-shaped grasping forceps (PN catch) in order to keep a safe pathological margin (Fig. 3A).Thoracoscopic wedge resections were performed using an endoscopic stapler under fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 3B). To confirm the lesion was really involved, the resected lung was cut, with a sufficient surgical margin followed by intraoperative pathological examination (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 2.

Horizontal (A) and vertical (C) settings of a C-arm-shaped fluoroscopic apparatus. Intraoperative fluoroscopic image of the radiopaque lipiodol marking spot in horizontal (B) and vertical (D) settings, respectively.

Fig. 3.

The lesion was grasped by PN catch forceps (A) and resected by an endoscopic stapler with a sufficient surgical margin (B). The lesion was located in resected lung and diagnosed as a metastatic tumor (rectal cancer) (C).

Results

All of the 60 nodules in 56 patients could be marked on the CT scan images before surgery. Concerning complications, pneumothorax occurred in 21 patients (37.5%), and only one patient required transient drainage. Although hemorrhaging in the lung parenchyma and hemosputum occurred in nine patients (16.1%) and one patient (1.8%), respectively, no patients were in serious condition; patients only required observation. The diameter of the lesions ranged from 3 mm to 20 mm as measured by preoperative CT (mean 10.5 mm ± 4.35 mm). The distance of needle puncture from the skin to the lesion ranged from 3 cm to 12 cm (mean 5.08 cm ± 1.55 cm). Of the 56 scheduled VATS procedures, 55 of 56 (98.2%) patients successfully underwent thoracoscopic resection of the lung with only intraoperative fluoroscopic guidance. In only one case, because the lipiodol injected lipiodol as a radiopaque was not clearly visualized by intraoperative fluoroscopy, the patient was converted to thoracotomy, and the lesion was resected by intraoperative direct palpation by the surgeon’s whole hand. Twenty-nine of 60 lesions were diagnosed as primary lung cancer by intraoperative frozen section or postoperative pathological examination. Twenty-two lesions were diagnosed as metastatic tumors, and nine lesions were diagnosed as other, such as benign inflammatory changes (Table 1). No intra- or postoperative mortality or morbidity was observed. The mean postoperative follow-up has been 38.5 months ± 19.8 months, and no local recurrences have occurred in any of the patients.

Table 1.

Pathological results of the lesions (60 lesions)

| Primary lung cancer | 29 |

| Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma | 15 |

| Adenocarcinoma with mixed subtypes | 11 |

| Papillary adenocarcinoma | 1 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 |

| Small cell carcinoma | 1 |

| Metastatic lung cancer | 22 |

| Hamartoma | 1 |

| Miscellaneous other lesions | 8 |

Discussion

The current study results indicate that small peripheral lung nodules can be safely localized using CT-guided lipiodol marking followed by fluoroscopically guided VATS resection. Complete VATS resection of the targeted lesions was successful in 98.3% (59 of 60 lesions) of cases, and this result was satisfactory. Watanabe et al. succeeded in visualizing and resecting all 174 nodules that were marked by preoperative CT-guided lipiodol marking;2) Ikeda et al. also performed thoracoscopic resection of all 29 impalpable pulmonary nodules with GGA that had been successfully marked by lipiodol.3) As just described, the preoperative lipiodol marking of pulmonary nodules has a high success rate in the performance of VATS pulmonary resection, and our rate of 98.3% was comparable to that in previous reports.2–5) Preoperative lipiodol marking of impalpable pulmonary nodules has several advantages over other marking methods such as metallic coil,6–9) hook wire,10–14) dye,15–17) and barium.18–20) First, it is possible to determine the proper central surgical cut lines because lipiodol can be injected adjacent to targeted lesions. Second, unlike barium and colored dye, colorless lipiodol is favorable for pathological examination. Indeed, 56 resected specimens in this study were submitted to intraoperative pathological examination, and all lesions were diagnosed promptly and accurately without any complaints from pathologists. Third, because injected lipiodol persists for a long time and remains confined to that area for a few days, it is not necessary to perform surgery on the day of marking. Finally, it remains possible that the materials used for marking, such as metallic coils or hook wires, may be missed in the thoracic space during the operation, thus interfering with resection of the lung using an endoscopic stapler; however, this is not the case with lipiodol marking.

Complications of lipiodol marking include pneumothorax, hemorrhaging in the lung parenchyma, hemoptysis, and systemic embolism of oily lipiodol. In this study, a pneumothoraxoccurred in 21 (37.5%) patients, but it was of a slight degree and asymptomatic, detected only by CT just after lipiodol marking, requiring intervention in only one case. A small amount of pulmonary hemorrhaging through an insertion route and a slight degree of hemosputum occurred in 9 (16.1%) and 1 (1.8%) patients, respectively. As Watanabe et al.’s previous study on a large scale, in which 174 nodules were marked by percutaneous lipiodol, no other serious complications occurred, such as systemic lipiodol embolism or air embolism.2) Although we did not encounter any instances of systemic embolism during the marking procedure, lipiodol poses a potential risk of systemic embolism, as the compound is insoluble in water. The marking procedure using lipiodol was first reported by Moon et al. in 1999, and despite the relative large amount of lipiodol (1 ml), there were only minor complication in 28 patients.4) In the present study, only 0.2 mL to 0.6 mL (mean 0.34 mL ± 0.13 mL) of lipiodol was used and was sufficient for marking; this amount is relatively smaller than that used in previous reports. We believe that using just a small amount of lipiodol minimizes the risk of systemic embolism. Furthermore, air embolism, a very rare complication that can be catastrophic, has been reported in cases using CT-guided marking hook wires.13,14) Concerning complications during a percutaneous lung needle biopsy, Tomiyama et al. reported that severe complications occurred in 74 of 9783 biopsies (0.75%), including 6 cases of air embolism (0.061%).21) However, although serious air embolism during lipiodol marking has not been reported, it should be given sufficient attention. Specifically, before injecting the lipiodol, the syringe must be withdrawn to confirm that no blood or air had flowed backward as described above.

All complications occurred during the CT-guided marking; they did not occur due to the injected lipiodol itself. Additionally, to avoid possible pleural dissemination and needle-insertion tract implantation of the tumor, we never insert the needle and inject lipiodol into the lesion itselfbut insert the needle and inject lipiodol very closely into adherent pulmonary parenchyma under CT-guided fluoroscopy.

Our study has several limitations. First, the relatively small number of patients in our study weakened the value of the statistical results. Second, we did not compare our results to those obtained by the use of other marking techniques, and our postoperative follow-up period was relatively short. Studies with larger, randomized patient populations are needed to identify the gold standard for marking pulmonary lesions.

The noteworthy advantage of our technique during operation is the direction of the C-arm-shaped fluoroscopyunit, which is set up horizontally (Fig. 2A). In previous reports from other groups, however, the C-arm-shaped fluoroscopy unit was set up vertically (Fig. 2C).2–5) The horizontal setting of the C-arm-shaped fluoroscopy unit made performing the operation more comfortable, less stressful, and also more likely successful, as the unit never interfered with the operator, and the fluoroscopic image of the radiopaque was clearer than that obtained using a vertical setting (Fig. 2B and 2D). To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports describing VATS with a lipiodol marking using a horizontal setting for a C-arm-shaped fluoroscopy unit.

CT-guided lipiodol marking may help to address the diagnostic dilemma of increasing numbers of small pulmonary nodules that are detected by HRCT to be growing. The horizontal setting of the C-arm-shaped fluoroscopy unit makes surgery followed by marking more likely to be successful.

Disclosure Statements

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

References

- 1).Suzuki K, Nagai K, Yoshida J, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for small indeterminate pulmonary nodules: indications for preoperative marking. Chest 1999; 115: 563-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Watanabe K, Nomori H, Ohtsuka T, et al. Usefulness and complications of computed tomography-guided lipiodol marking for fluoroscopy-assisted thoracoscopic resection of small pulmonary nodules: experience with 174 nodules. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006; 132: 320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Ikeda K, Nomori H, Mori T, et al. Impalpable pulmonary nodules with ground-glass opacity: Success for making pathologic sections with preoperative marking by lipiodol. Chest 2007; 131: 502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Moon SW, Wang YP, Jo KH, et al. Fluoroscopy-aided thoracoscopic resection of pulmonary nodule localized with contrast media. Ann Thorac Surg 1999; 68: 1815-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Kawanaka K, Nomori H, Mori T, et al. Marking of small pulmonary nodules before thoracoscopic resection: injection of lipiodol under CT-fluoroscopic guidance. Acad Radiol 2009; 16: 39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Lizza N, Eucher P, Haxhe JP, et al. Thoracoscopic resection of pulmonary nodules after computed tomographic-guided coil labeling. Ann Thorac Surg 2001; 71: 986-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Miyoshi T, Kondo K, Takizawa H, et al. Fluoroscopy-assisted thoracoscopic resection of pulmonary nodules after computed tomography–guided bronchoscopic metallic coil marking. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006; 131: 704-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Toba H, Kondo K, Miyoshi T, et al. Fluoroscopy-assisted thoracoscopic resection after computed tomography-guided bronchoscopic metallic coil marking for small peripheral pulmonary lesions. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013; 44: e126-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Mayo JR, Clifton JC, Powell TI, et al. Lung nodules: CT-guided placement of microcoils to direct video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical resection. Radiology 2009; 250: 576-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Mack MJ, Gordon MJ, Postma TW, et al. Percutaneous localization of pulmonary nodules for thoracoscopic lung resection. Ann Thorac Surg 1992; 53: 1123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Dendo S, Kanazawa S, Ando A, et al. Preoperative localization of small pulmonary lesions with a short hook wire and suture system: experience with 168 procedures. Radiology 2002; 225: 511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Wicky S, Dusmet M, Doenz F, et al. Computed tomography-guided localization of small lung nodules before video-assisted resection: experience with an efficient hook-wire system. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002; 124: 401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Horan TA, Pinheiro PM, Araújo LM, et al. Massive gas embolism during pulmonary nodule hook wire localization. Ann Thorac Surg 2002; 73: 1647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Sakiyama S, Kondo K, Matsuoka H, et al. Fatal air embolism during computed tomography-guided pulmonary marking with a hook-type marker. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003; 126: 1207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Kerrigan DC, Spence PA, Crittenden MD, et al. Methylene blue guidance for simplified resection of a lung lesion. Ann Thorac Surg 1992; 53: 163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Endo M, Kotani Y, Satouchi M, et al. CT fluoroscopy-guided bronchoscopic dye marking for resection of small peripheral pulmonary nodules. Chest 2004; 125: 1747-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Shentu Y, Zhang L, Gu H, et al. A new technique combining virtual simulation and methylene blue staining for the localization of small peripheral pulmonary lesions. BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Asano F, Shindoh J, Shigemitsu K, et al. Ultrathin bronchoscopic barium marking with virtual bronchoscopic navigation for fluoroscopy-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. 2004; 126: 1687-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Okumura T, Kondo H, Suzuki K, et al. Fluoroscopy-assisted thoracoscopic surgery after computed tomography-guided bronchoscopic barium marking. Ann Thorac Surg 2001; 71: 439-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Iwasaki Y, Nagata K, Yuba T, et al. Fluoroscopy-guided barium marking for localizing small pulmonary lesions before video-assisted thoracic surgery. Respir Med 2005; 99: 285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Tomiyama N, Yasuhara Y, Nakajima Y, et al. CT-guided needle biopsy of lung lesions: A survey of severe complication based on 9783 biopsies in Japan. Eur J Radiol 2006; 59: 60-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]