Abstract

Purpose: The study evaluates the changes in quality of life (QOL) six months after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) related to the patients’ age.

Methods: The total of 243 consecutive patients completed the Nottingham Health Profile Questionnaire part 1 before and six months after CABG. Postoperative questionnaire was completed by 226 patients. Patients were divided into four examined groups (<50, 50–59, 60–69 and ≥70 years), according to their age.

Results: Six months after CABG, the quality of life in different sections has been significantly improved in most patients.The analysis of the relation between the age and the changes in QOL of patients six months after CABG showed a significant correlation among the patients’ age and the improvement of QOL in the sections of physical mobility (r = 0.18, p = 0.008), social isolation (r = 0.17, p = 0.01) and energy ( r = 0.21, p = 0.002). The most prominent improvement was found in older patients. The age was not an independent predictor of QOL deterioration after CABG.

Conclusions: The most noticeable improvement of QOL six months after CABG was found in older patients. Age is not the independent predictor of deterioration of QOL after CABG.

Keywords: age groups, coronary artery bypass, quality of life

Introduction

Starting from 1970 to present days, the evaluation of quality of life (QOL) has grown from a “small cottage industry to a large academic enterprise.”1)

Unlike the most of the measurable therapeutic achievements which are physician-centered, the quality of life is patient-oriented methodology. Good QOL implies the person’s ability to function normally on a daily basis and to be satisfied with the participation in daily activities. The ability to perform daily activities includes preserved physical mobility, independence, sufficient energy for self-care activities, social contacts, emotional stability, absence of pain or other symptoms of discomfort and adequate sleep and rest.

Aging could increase the risk for chronic diseases and disabilities and could have an significant impact on quality of life, but this relationship between the age and the risk is not entirely clear. Some studies have shown that the elderly tend to evaluate their health as satisfactory even in the presence of severe diseases;2,3) this response may be the result of adaptation to existing discomforts and difficulties.4)

More and more elderly patients tend to undergo coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG).5) When making a decision on a possible surgical treatment the generally poorer cardiac status, a higher number of comorbidities and a higher perioperative risk of elderly patients must be taken into account. In addition, a number of studies dealing with changes in QOL after CABG brought out conflicting views and conclusions.

Taking into account the uncertain relationship between age of patients and changes in quality of life after coronary artery bypass surgery and to some extent contradictory views on the topic, we have designated the following research objectives:

To identify the differences in preoperative quality of life between patients of different ages.

To determine changes in the quality of life in different age groups of patients six months after coronary artery bypass surgery.

To confirm the relationship between the age of patients and changes in quality of life six months after coronary artery bypass.

To investigate whether the advanced age may be the predictor of the deterioration of quality of life after coronary artery bypass.

Materials and Methods

A total of 243 consecutive patients with obstructive coronary artery disease were studied. The patients uderwent elective coronary artery bypass surgery (on pump procedure) at the Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases “Dedinje’’, Belgrade. All the patients acknowledged and complied with the participation in the study. The implementation of the study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases “Dedinje’’, Belgrade.

The questionnaire in Serbian was modeled on the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) questionnaire – part one, designed by Hunt SM, et al.6) NHP questionnaire is a generic scale, and its purpose is not to measure the extent of the disease, but rather the indicators of health limitations. NHP questionnaire compares the quality of life in patients of different cultures and populations. It also overcomes the tendency of elderly persons to interpret their health as good, regardless the objective condition, by focusing not on health itself but on experienced distress and discomfort.4) NHP was originally written in English, and was subjected to a rigorous translation into Serbian language and linguistic validation. The first part contains 38 subjective statements taken from patients, divided into six sections: physical mobility (PM), social isolation (SI), emotional reaction (ER), energy (En), pain and sleep. Number of the statements in each group ranges from three in section En to nine in the compartment ER. Patients were interviewed immediately before and 6 months after CABG. The answer to each question is of binary type (yes or no). Scores were ranked from 0 to 100, by adding weight to every positive response as specified by the Thurstone’s method of paired compares. Weightness of the response is determined by examinination of a large general population sample.7) A higher score indicates greater deterioration of the quality of life. Postoperative questionnaires were completed by 226 patients. For the reason of effective comparison of pre- and postoperative QOL and productive presentation of the results, the patients were divided into four groups (<50, 50–59, 60–69, i ≥70), according to their age.

The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The relation between preoperative quality of life and patient’s age was determined by Spearman’s correlation. In patients of different age groups, the preoperative and postoperative results for each section of quality of life were compared using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs rank test. Pre- and postoperative results in each of the QOL sections were compared with the reference values obtained by the examination of a large population samples;4) these reference values were adjusted for the gender and age of the subjects participated in the study. The differences between the NYHA scores in pre- and postoperative patients of different age were tested using the same method (Wilcoxon matched-pairs rank test). The correlation between the changes in QOL after the surgery and patients’ age was performed using Spearman’s correlation procedure.

To determine the independent preoperative factors influencing the change of QOL (quantified in a binary scale – worsened or not worsened) after CABG, we performed logistic regression. In examination of predictors of QOL impairment, patients with no changes in postoperative QOL were joined to patients with improvement of QOL. Every category of variables in every section of QOL was analyzed using the univariate logistic regression. Variables with a level of significance less then or equal to 0.20 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression.

Results

The preoperative features of examined population are presented in Table 1. Among patients undergoing CABG 80% of them were male, with mean age 58.3 ± 8.3 and 20% female, with mean age 61.6 ± 6.1. The age distribution was as follows: 35/226 (16%) patients were <50, 80/226 (35%) were 50–59, of 91/226 (40%) were 60 to 69, and 20/226 (9%) patients were 70 or older.

Table 1.

Baseline details of the population study

| Variable | No. of patients | Percentage | Variable | No. of patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Angina pectoris (CCS) | ||||

| Male | 181 | 80 | No angina | 29 | 13 |

| Female | 45 | 20 | I | 27 | 12 |

| Age (y) | II | 112 | 50 | ||

| <50 | 35 | 16 | III | 55 | 24 |

| 50–59 | 80 | 35 | IV | 3 | 1 |

| 60–69 | 91 | 40 | NYHA functional class | ||

| ≥70 | 20 | 9 | I | 22 | 10 |

| Marital status | II | 119 | 53 | ||

| Married | 201 | 89 | III | 80 | 35 |

| No married | 25 | 11 | IV | 5 | 2 |

| Risk factors | Ejection fraction (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 157 | 72 | <30 | 26 | 11 |

| Smoking | 30–50 | 108 | 48 | ||

| Smokers | 102 | 45 | ≥50 | 92 | 41 |

| Former smokers | 64 | 28 | Segmental wall motion | ||

| Non smokers | 60 | 27 | Normal | 42 | 19 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 134 | 59 | Abnormal | 184 | 81 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 45 | 20 | Duration of CHD (y) | ||

| Heredity | 130 | 58 | ≤1 | 88 | 39 |

| Obesity (BMI>30) | 59 | 26 | 1–10 | 123 | 54 |

| Stress | 139 | 62 | >10 | 15 | 7 |

| Physical inactivity | 111 | 49 | Comorbid diseases** | ||

| No of vessel diseased | None | 121 | 54 | ||

| Left main artery | 16 | 7 | Chronic obstructive | ||

| One vessel* | 18 | 8 | pulmonary disease | 6 | 3 |

| Two vessels* | 50 | 22 | Renal failure | 3 | 1 |

| Three vessels* | 142 | 63 | Cerebral or peripheral | ||

| Prior myocardial infarction | vascular disease | 41 | 18 | ||

| Yes | 134 | 59 | Other | 10 | 4 |

| No | 92 | 41 | Euro SCORE | ||

| Prior heart operation | 0 – 2 | 86 | 38 | ||

| Yes | 11 | 5 | 3 – 5 | 100 | 44 |

| No | 215 | 95 | ≥6 | 40 | 18 |

*Without left main artery. **Diabetes mellitus showed with the risk factors for ischemic heart disease. BMI: body mass index; CCS: Canadian Cardiology Society; CHD: coronary heart disease; EuroSCORE: European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

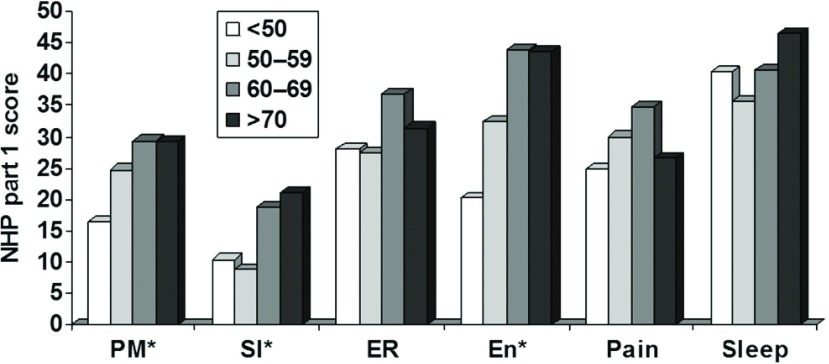

Preoperative quality of life varied among different age groups (Fig. 1). Elderly patients before CABG have a significantly worse QOL (higher NHP part 1 score) in sections of physical mobility (r = 0.22, p = 0.001), social isolation (r = 0.16, p = 0.009) and energy (r = 0.23, p = 0.001). No significant differences were found in other QOL domains.

Fig. 1.

The mean preoperative NHP QOL score in patients of different age groups *p <0,01. The relation between the preoperative quality of life and the patients age: PM – r = 0.22, p = 0.001; SI – r = 0.16, p = 0.009; ER – r = 0.07, p = 0.26; En – r = 0.23, p <0.001; Pain – r = 0.11, p = 0.09; Sleep – r = 0.07, p = 0.29. PM: physical mobility; SI: social isolation; ER: emotional reaction; En: energy.

The operative features of examined population are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patients operative details

| No. of patients | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of grafts | ||

| 1 | 17 | 8 |

| 2 | 69 | 31 |

| 3 | 109 | 48 |

| 4 | 26 | 11 |

| 5 | 5 | 2 |

| Type of grafts | ||

| LITA | 184 | 81 |

| RITA | 4 | 2 |

| LITA + RITA | 6 | 3 |

| Venous grafts only | 32 | 14 |

| Complications | ||

| No | 157 | 69 |

| Low cardiac output | 7 | 3 |

| Mechanical ventilation >24 h | 9 | 4 |

| Reoperation for bleeding | 3 | 1 |

| Sternal wound infection | 7 | 3 |

| Perioperative myocardial infarction | 3 | 1 |

| Pericardial effusion | 13 | 6 |

| Arrhythmic complications | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 25 | 11 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 2 | 1 |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 2 | 1 |

| Abdominal complications | 5 | 2 |

| Other | 13 | 6 |

| Mortality | ||

| <30 days | 6 | 2 |

| 1 – 6 months | 7 | 3 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; LITA: left internal thoracic artery; RITA: right internal thoracic artery.

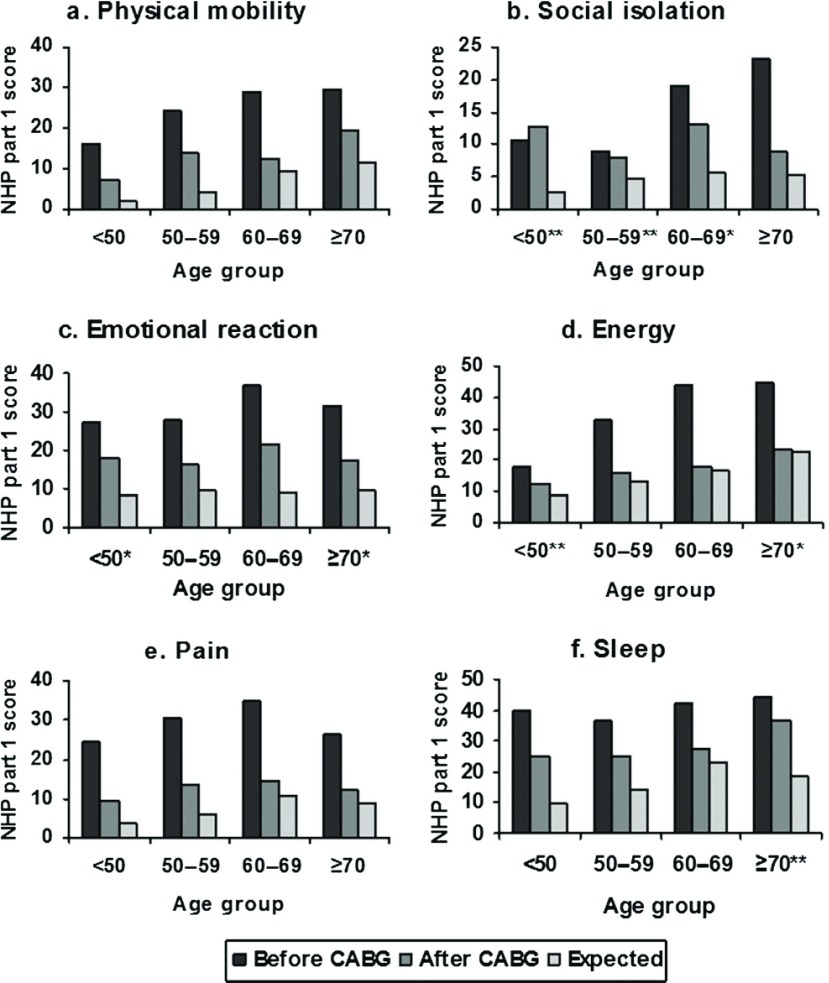

Six months after CABG quality of life in all sections is significantly improved in most patients. The average NHP part 1 scores before and after CABG and the comparison with reference values in patients of different age groups are shown in Fig. 2. The patients below the age of 50 had the significant improvement in sections of physical mobility, emotional reactions, pain and sleep. Their quality of life in sections of social isolation and the energy has not significantly changed after surgery. Patients of the age group 60–69 have significant improvements in all sections of QOL after CABG, as well as patients of the age group 50–59, with the exception of social isolation section. Patients aged 70 or more had noticeably better scores in all sections except sleep (no significant difference was found in this section). Figure 2 shows that the patients of certain age groups may fully approximate to the reference values for the age and the gender in some sections of postoperative QOL (e.g., patients of the age group 50–59 and 60–69 in the section related to energy, respectively). On the other hand, in other age groups postoperative QOL remains noticeably inferior compared to the reference values (e.g., in patients <50, in SI section).

Fig. 2.

The mean NHP part 1 scores in each section of QOL in patients of different age groups, before and after CABG in comparison with referent values. p <0.01 for all sections and age groups except for *p <0.05 i **p >0.05.

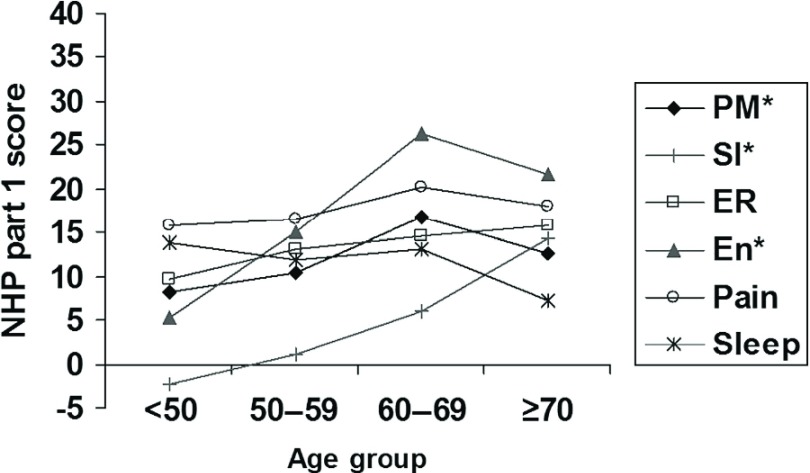

The results of the correlation analysis six months after CABG surgery demonstrated a significant relationship between the age of the patient and improvement of QOL in sections of physical mobility (r = 0.18, p = 0.008), social isolation (r = 0.17, p = 0.01) and energy (r = 0.21, p = 0.002) (Fig. 3). The major improvement was found in older patients. Improvement of QOL in section FP and En increases with ageing up to the age group 60–69, where the greatest improvement was noted. In the age group <50 a deterioration in QOL in section SI was registered (although not statistically significant); a progressive improvement of QOL in this section was noticed thenceforth in the older age groups, with a maximum achievement in patients of age 70 and more. There is no significant correlation between the extent of changes of QOL in sections of emotional reactions, pain and sleep and the age of the patients (p <0.05) (Fig. 3). Patients’ age met the criteria for entering the multivariate regression only in a single section energy (according to the evidence obtained with the previous univariate regression), but the results demonstrated that it was not the significant predictor of the deterioration of quality of life (beta –0.550, p = 0.087, 95% CI 0.307–1.084).

Fig. 3.

The changes in postoperative NHP score in correlation with patients age groups (*p <0,01). On the abscissa are presented the age groups of the studied population of patients. The average change of QOL score is shown on ordinate (the difference between pre- and post - CABG quality of life). Values above zero indicate an average improvement, while values below zero indicate an average deterioration in QOL for a given age group (PM – r = 0.18, p = 0.008; SI – r = 0.17, p = 0.01; ER – r = 0.06, p = 0.40; En – r = 0.21, p = 0.002; Pain – r = 0.05, p = 0.49; Sleep – r = –0.04, p = 0.57). PM: physical mobility; SI: social isolation; ER: emotional reaction; En: energy; r: Coefficient of correlation.

Discussion

The quality of life implicates the unique personal perception, the way in which people assess their own health and non-medical aspects of their life. Intriguing assertion that “cold clinical science pays little attention to the patient as a human being’’,8) leads to a general sense that QOL delineate a positive shift in clinical studies, in terms of the patient’s overall well-being.

A number of studies address the impact of age on the quality of life of the general population. The authors of NHP questionnaire examined the quality of life of people of different age groups and both genders, in a large population sample.4) Older patients and women generally have poorer QOL. In general, QOL declines with age in categories of physical mobility, energy, pain, and sleep. Although there are many studies dealing with the health of elderly, only a small number of them were dedicated to the investigation of the middle and younger age people, despite the reports on increasing emotional and social discomfort during the “midlife crisis”.9)

Preoperative quality of life differs among the age groups (Fig. 1). Older people usually have more problems that can potentially disrupt QOL. The results of the study shows that preoperative QOL deteriorates with age and that patients of 60 years or more have poorer QOL scores compared to younger in the sections of PM, SI, and En (Fig. 1). The lack of differences in other areas of QOL may be explained by the higher compliance with the difficulties as an integral part of the aging process.

The results of previous studies considering the changes in QOL after CABG often appear contradictory. Some studies stated that older patients undergoing CABG had a significantly lower preoperative functional level which may be retained up to 6 months after surgery. However, functional improvement after surgery was not significantly different among the diverse age groups.10) There were also several reports on the improvement in quality of life and a marked improvement of functional ability, along with the acceptable operative risk in patients older than 80, whose QOL after CABG surgery reached the average QOL characterizing the population of the same age.11–14) Application of combined arterial and venous grafts in people of 80 years and more provides better results in terms of survival, postoperative complications, and QOL comparing to the use of a vein grafts only.15,16) A group of Swedish authors, however, found that patients older than 60 express a tendency of slight improvement in QOL compared with younger patients five years after CABG.17) Guadagnolo et al. evaluated and compared the outcomes after elective CABG in patients younger and older than 65. They found that, in general, both groups of patients have similar functional benefits and that the factors associated to it are not different in various age groups.18)

Presently, the percentage of elderly patients undergoing CABG show a substantial increase.19) The highest rise in the number of incidence of coronary artery disease was recorded in the age group of 85 years and above.20,21) They usually have more severe coronary artery disease, presence of comorbidities and the worse overall preoperative status (higher incidence of the left main coronary artery disease, multivessel disease, left ventricular dysfunction, previous cardiac operations, often accompanied with valvular disease).

The TIME study demonstrated more pronounced reduction of CAD symptoms and the greater improvement of quality of life in patients older than 75 who underwent CABG, compared to those with non-surgical treatment. Therefore, the researchers stated that all those patients should be surgically treated, regardless of their greater perioperative risk.22) Carey et al., examining the quality of life after CABG in four different age groups, estimated a higher level of in-hospital mortality in elderly patients who underwent combined interventions, but not in those who underwent CABG only. The survival probability was significantly higher in patients <60 years. However, the improvement was more pronounced and lasting in patients above 60 years of age, and the proportion of re-operations was lower.23)

The results of our study show the enhanced QOL six months after CABG surgery in the majority of patients regardless of age. The lack of the significant improvement was registered only in patients <50 years in sections SI and En, in patients 50–59 years in SI section, and in patients aged 70 or more in sleep section (Fig. 2). In some patients, the quality of postoperative QOL approached the reference values for age and gender. There was a positive correlation between the age of the patient and improvement of QOL in Section FP, SI and En. The largest benefit in QOL after surgery was registered in patients aged 60–69 years (Fig. 3). In patients <60 years the improvement of QOL in section SI was not significant, although the symptoms after CABG are, generally, less restrictive in this group. Younger patients have more difficulties to participate in the activities typical for their age, comparing to their peers who do not have restrictions of the kind. That is not the case in the older age groups. For the same reason, there is no improvement in postoperative QOL regarding section energy, in patients <50. However, the younger age usually means better physical condition, clearer mental functioning, improved cardiac status and the lower incidence of comorbidities. Therefore, younger patients have better results after CABG in most sections comparing to the elderly. The elderly gain less long-term benefit from CABG regarding the QOL and survival.24,25) On the other hand, older patients often have unmet physical, social and emotional needs and prefer to admit and discuss their problems. Although elderly patients have most significant improvement of QOL after surgery comparing to the preoperative period (Fig. 3), their QOL both before and after surgery tend to be poorer comparing with younger patients (Fig. 2).

The most prominent improvement of QOL in elderly patients after CABG falls precisely in those sections in which their QOL prior to CABG was significantly worse compared with younger (PM, SI, and En). These findings suggest that the improvement in QOL after CABG depends on the level of preoperative QOL impediment. The worse preoperative QOL means that the chances for its significant improvement six months after CABG are greater. The age itself was not an independent predictor of deterioration in quality of life after CABG.

In addition, elderly patients undergoing CABG are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality related to the surgery; this risk is directly proportional to their age, the level of impairment of the left ventricle function, increased severity of coronary disease, co-morbid states and urgency of the operation. However, in spite of these, a large number of these patients can still achieve a satisfactory functional recovery and stable improvement of QOL.

Conclusions

Age, by itself, should not be a contraindication for CABG, if the estimation of long-term benefit of surgery prevails over the coexsistent risk. It is therefore important to assess the positive and negative developments in the prognosis, functional status and quality of life; the assessment results may favor surgical treatment, invasive non-surgical cardiovascular treatment or continuation of medication therapy. The patient and physician should jointly consider the potential benefits in terms of improved QOL and long-term survival, as well as the real risks that surgery entails.

Funding

This research received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosures Statement

The Authors declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors owe special gratitude to the patients and staff at the Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases “Dedinje”.

References

- 1).Gill TM, Feinstein AR. A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA 1994; 272: 619-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Maddox GL, Douglass EB. Aging and individual differences: a longitudinal analysis of social, psychological, and physiological indicators. J Gerontol 1974; 29: 555-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Williamson J, Stokoe IH, Gray S, et al. Old people at home their unreported needs. Lancet 1964; 283: 1117-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Hunt SM, McEwen J, McKenna SP. Perceived health: age and sex comparisons in a community. J Epidemiol Community Health 1984; 38: 156-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Shan L, Saxena A, McMahon R, et al. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery in the elderly: a review of postoperative quality of life. Circulation 2013; 128: 2333-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Hunt SM, McKenna SP, McEwen J, et al. The nottingham health profile: subjective health status and medical consultations. SocSci Med 1981; 15: 221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).McKenna SP, Hunt SM, McEwen J. Weighting the seriousness of perceived health problems using Thurstone’s method of paired comparisons. Int J Epidemiol 1981; 10: 93-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Pocock SJ. A perspective on the role of quality-of-life assessment in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1991; 12: 257S-265S.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Levinson DJ. The mid-life transition: a period in adult psychosocial development. Psychiatry 1977; 40: 99-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Hedeshian MH, Namour N, Dziadik E, et al. Does increasing age have a negative impact on six-month functional outcome after coronary artery bypass? Surgery 2002; 132: 239-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Sen B, Niemann B, Roth P, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes in octogenarians after coronary artery bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012; 42: 102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Shigemitsu O, Hadama T, Miyamoto S, et al. Early and long-term results of cardiovascular surgery in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001; 7: 223-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Caceres M, Cheng W, De Robertis M, et al. Survival and quality of life for nonagenarians after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 95: 1598-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Fruitman DS, MacDougall CE, Ross DB. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians: can elderly patients benefit? Quality of life after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 1999; 68: 2129-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Kurlansky PA, Williams DB, Traad EA, et al. Arterial grafting results in reduced operative mortality and enhanced long-term quality of life in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg 2003; 76: 418-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Baig K, Harling L, Papanikitas J, et al. Does coronary artery bypass grafting improve quality of life in elderly patients? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013; 17: 542-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Herlitz J, Wiklund I, Sjöland H, et al. Impact of age on improvement in health-related quality of life 5 years after coronary artery bypass grafting. Scand J Rehabil Med 2000; 32: 41-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD. Comparison of patient-reported outcomes after elective coronary artery bypass grafting in patients aged greater than or equal to and less than 65 years. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70: 60-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Japanese Associate for Coronary Artery Surgery (JACAS). Coronary artery surgery results 2013, in Japan. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 20: 332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Ghanta RK, Shekar PS, McGurk S, et al. Long-term survival and quality of life justify cardiac surgery in the very elderly patient. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 92: 851-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Ivanov J, Weisel RD, David TE, et al. Fifteen-year trends in risk severity and operative mortality in elderly patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation 1998; 97: 673-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).TIME Investigators. Trial of invasive versus medical therapy in elderly patients with chronic symptomatic coronary-artery disease (TIME): a randomised trial. Lancet 2001; 358: 951-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Carey JS, Cukingnan RA, Singer LK. Quality of life after myocardial revascularization. Effect of increasing age. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992; 103: 108-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Hokkanen M, Järvinen O, Huhtala H, et al. A 12-year follow-up on the changes in health-related quality of life after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014; 45: 329-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Krane M, Voss B, Hiebinger A, et al. Twenty years of cardiac surgery in patients aged 80 years and older: risks and benefits. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 91: 506-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]