Abstract

Histone acetylation is sensitive to the availability of acetyl-CoA. However, the extent to which metabolic alterations in cancer cells impact tumor histone acetylation has been unclear. Here, we discuss our recent findings that oncogenic AKT1 activation regulates histone acetylation levels in tumors through regulation of acetyl-CoA metabolism.

Keywords: ATP-citrate lyase, AKT1, acetyl-CoA, cancer metabolism, histone acetylation

Abbreviations

- ACLY

ATP-citrate lyase

- ACSS2

acyl-CoA synthetase short chain family member 2

- IDH

isocitrate dehydrogenase

- PDC

pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

- SAM

S-adenosyl methionine

- TET2

tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2

- UDP-GlcNAc

uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine

Metabolism is extensively rewired in cancer cells. These metabolic alterations are crucial for generation of the building blocks, reducing equivalents, and ATP needed for synthesis of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. In addition, increasing evidence suggests that metabolic reprogramming plays important roles in promoting growth and proliferation beyond direct production of energy or macromolecules. For example, novel nuclear functions for metabolic enzymes, such as pyruvate kinase M2, have been uncovered. It has also become increasingly clear that certain post-translational modifications are sensitive to metabolite availability, raising the possibility that metabolic alterations in cancer cells could have a profound influence on signal transduction and epigenetics.

In certain cases, it is already established that metabolites regulate the cancer cell epigenome. Tumors with IDH1/2 mutations, for example, generate high levels of (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate, which interferes with normal activities of α-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes such as tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 (TET2), resulting in epigenetic and transcriptional deregulation.1 Even beyond pathological circumstances such as this, accumulating evidence indicates that metabolic modulation of signaling, transcription, and chromatin can dramatically impact cellular activities. Metabolites can thus exert dual functions in providing both building blocks and instructions to the cell. Emerging at the forefront of such regulation is acetyl-CoA, a metabolite that plays key roles in glucose, amino acid, and lipid metabolism, but is also required for lysine and N-terminal acetylation.

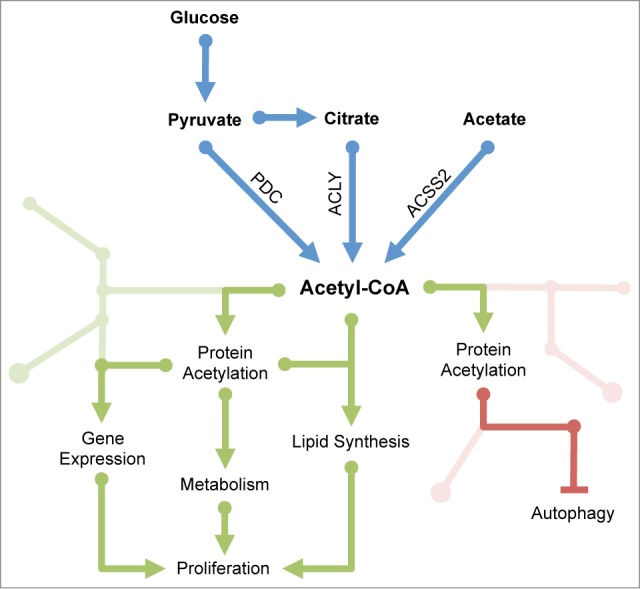

Acetyl-CoA is compartmentalized in cells into mitochondrial and nuclear–cytoplasmic pools. Outside of mitochondria, ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) and acyl-CoA synthetase short chain family member 2 (ACSS2, also known as ACECS1) serve as major generators of acetyl-CoA.2 In addition to these 2 enzymes, a third mechanism for production of extra-mitochondrial acetyl-CoA was identified very recently, in which the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) translocates into the nucleus enabling generation of nuclear acetyl-CoA from pyruvate.3 As a metabolite at the crossroads of catabolic and anabolic processes and the substrate for acetyltransferase enzymes, acetyl-CoA is strongly positioned to convey information about cellular metabolic status. Acetyl-CoA is dynamically regulated within the cell in response to its nutritional conditions, and lysine acetylation (of histones and other proteins, including many metabolic enzymes) has been implicated in controlling gene expression, metabolism, and autophagy in response to changes in nutrient availability or the cell's metabolic state.4-8 These data suggest that acetylation may be critical for promoting proliferation-related gene expression and anabolic metabolism, while suppressing catabolic processes such as autophagy, when nutrient levels are high (Fig. 1). Acetyl-CoA and acetylation could thus represent crucial components of the cell's nutrient-sensing repertoire.

Figure 1.

A cancerous web: acetyl-CoA promotes growth and proliferation through multiple mechanisms. Outside of mitochondria, acetyl-CoA can be generated from citrate by ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY), from acetate by acyl-CoA synthetase short chain family member 2 (ACSS2), and from pyruvate by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC), which was recently reported to translocate from mitochondria into the nucleus. Acetyl-CoA has long been known to support growth and proliferation through its roles in the synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol. Acetyl-CoA also participates in the regulation of histone acetylation and gene expression, is required for acetylation of numerous metabolic enzymes, and suppresses autophagy. Although many details remain to be elucidated, it is clear that acetylation plays crucial roles in modulating cellular activities, including decisions to grow and divide, in accordance with metabolic resources.

Cancer cells exhibit substantial epigenetic alterations that contribute to the acquisition of all hallmarks of cancer.9 How extensively might metabolic reprogramming contribute to this epigenetic deregulation? It is clear from a number of studies over the past several years that acetylation of histones is sensitive to the availability of acetyl-CoA.2 We have recently shown that levels of acetyl-CoA and the ratio of acetyl-CoA:CoA are regulated dynamically by glucose availability in mammalian cells, and that nuclear levels of both acetyl-CoA and CoA can impact overall histone acetylation levels.6 In the context of cancer biology, though, what is the significance of these observations? How is acetyl-CoA metabolism altered in cancer cells and is metabolism a significant contributor to tumor histone acetylation levels? If so, how does this impact tumor growth?

We have recently attempted to address the first question—is oncogenic control of acetyl-CoA metabolism a major determinant of cancer cell histone acetylation levels? We found that constitutive activation of the PI3 kinase-AKT1 pathway does indeed promote elevated histone acetylation, both in vitro in cancer cell lines and in vivo in 2 different mouse models.6 The effects of AKT1 on histone acetylation rely on glucose-dependent production of acetyl-CoA, and when AKT1 is inhibited, both acetyl-CoA and histone acetylation levels decrease.6 Interestingly, although histone acetylation levels are regulated by glucose, phosphorylation of ACLY downstream of AKT1 allows histone acetylation to be sustained during glucose limitation.6 Such a mechanism could potentially enable tumor cells to maintain histone acetylation in a heterogeneous microenvironment. In support of this possibility, global histone acetylation levels were found to correlate significantly with pAKT(Ser473) in human gliomas and prostate tumors.6 These data strongly suggest that metabolic reprogramming mediated by AKT1 could indeed be a major contributor to histone acetylation levels in tumors.

What this ultimately means for tumor development and growth will require further investigation. In glioblastoma cells, genes favored in the presence of high acetyl-CoA include those with roles in cell cycle and DNA replication.6 During glucose limitation, artificially increasing acetyl-CoA levels stimulated expression of these genes, but did not promote proliferation unless other glucose-dependent metabolites were provided.6 Thus, acetyl-CoA may provide a pro-growth signal to the cell by regulating relevant gene expression programs. Notably, elevated histone acetylation is observed upon oncogene activation in mice prior to the appearance of tumors.6 Future studies could thus also consider the intriguing possibility that oncogene-induced metabolic regulation of histone acetylation might promote a favorable epigenetic context for malignant transformation. Finally, it is worth considering that whatever the role of acetyl-CoA–regulated histone acetylation in tumorigenesis, it may well represent the tip of the iceberg since oncogene-induced metabolic alterations may also impact levels of other key metabolites needed for chromatin modifications, such as the methyl donor S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) or UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), the substrate for O-GlcNAc modification.10 It will be of interest to assess whether therapeutics targeting cancer metabolism also impact chromatin modifications. If they do, might this interaction play a role in therapeutic efficacy or sensitize cells to drugs that target epigenetics?

Tumorigenesis is often considered a linear process whereby gene mutations or epigenetic alterations cause oncogenic signaling and transcription that then promote growth and survival through multiple mechanisms, including rewiring metabolism. The finding that AKT1-dependent metabolic reprogramming has a significant impact on the tumor epigenome provides evidence that cancer epigenetics, signaling, and metabolism are engaged in a complex interplay. It will be important to continue investigating how each of these components regulate one another in order to better understand the genesis and progression of cancer, as well as to elucidate more effective treatment strategies.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1. Losman JA, Kaelin WG, Jr. What a difference a hydroxyl makes: mutant IDH, (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate, and cancer. Genes Dev 2013; 27:836-52; PMID:23630074; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.217406.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wellen KE, Thompson CB. A two-way street: reciprocal regulation of metabolism and signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012; 13:270-6; PMID:22395772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sutendra G, Kinnaird A, Dromparis P, Paulin R, Stenson TH, Haromy A, Hashimoto K, Zhang N, Flaim E, Michelakis ED. A nuclear pyruvate dehydrogenase complex is important for the generation of acetyl-CoA and hyistone acetylation. Cell 2014; 158:84-97; PMID:24995980; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xiong Y, Guan KL. Mechanistic insights into the regulation of metabolic enzymes by acetylation. J Cell Biol 2012; 198:155-64; PMID:22826120; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201202056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cai L, Sutter BM, Li B, Tu BP. Acetyl-CoA induces cell growth and proliferation by promoting the acetylation of histones at growth genes. Mol Cell 2011; 42:426-37; PMID:21596309; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee JV, Carrer A, Shah S, Snyder NW, Wei S, Venneti S, Worth AJ, Yuan ZF, Lim HW, Liu S, et al. Akt-dependent metabolic reprogramming regulates tumor cell histone acetylation. Cell Metab 2014; 20:306-19; PMID:24998913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wellen KE, Hatzivassiliou G, Sachdeva UM, Bui TV, Cross JR, Thompson CB. ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science 2009; 324:1076-80; PMID:19461003; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1164097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marino G, Pietrocola F, Eisenberg T, Kong Y, Malik SA, Andryushkova A, Schroeder S, Pendl T, Harger A, Niso-Santano M, et al. Regulation of autophagy by cytosolic acetyl-coenzyme A. Mol Cell 2014; 53:710-25; PMID:24560926; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Azad N, Zahnow CA, Rudin CM, Baylin SB. The future of epigenetic therapy in solid tumours–lessons from the past. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013; 10:256-66; PMID:23546521; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lu C, Thompson CB. Metabolic regulation of epigenetics. Cell Metab 2012; 16:9-17; PMID:22768835; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]