Abstract

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women in the United States. Recent extensive genomic analyses of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), particularly the most common and deadly form of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, have provided important insights into the repertoire of molecular aberrations that are characteristic for this malignancy. However, interpretation of the discovered aberrations is complicated because the origin and mechanisms of progression of EOC remain uncertain. Here, we summarize current views on the cell of origin of EOC and discuss recent findings of a cancer-prone stem cell niche for ovarian surface epithelium, one of the major likely sources of EOC. We also outline future directions and challenges in studying the role of stem cell niches in EOC pathogenesis.

Keywords: cancer propagating cells, cell of cancer origin, malignant transformation, ovarian cancer, stem cells

Abbreviations

- ALDH

aldehyde dehydrogenase

- BrdU/IdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine/5-iodo-2′deoxyuridine

- CPC

cancer propagating cell

- EOC

epithelial ovarian cancer

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- HGSOC

high-grade serous carcinoma

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- OSE

ovarian surface epithelium

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- STIC

serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma

- TE

tubal epithelium

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most common and lethal gynecological malignancy worldwide and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death in females.1,2 Annually, ovarian cancer accounts for 140,200 deaths globally, with a 65% estimated mortality rate for 2014.2 The high mortality rate is attributed to the frequent diagnosis of ovarian cancer at advanced stages when the cancer is no longer localized.1 The 5-year survival rate for ovarian cancer diagnosed at the early localized stages is approximately 91%, contrasting with the 30% 5-year survival rate for ovarian cancer diagnosed at advanced stages.2

Approximately 90% of primary malignant ovarian neoplasms are of epithelial origin. Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is classified by morphological criteria such as serous, mucinous, endometrioid, and clear cell types.3 High-grade serous carcinomas (HGSOC) are the most common and deadly form of ovarian carcinomas, constituting approximately 70% of cases of EOC. Recently, an extensive integrated genomic analysis of 489 HGSOCs cataloged the repertoire of molecular aberrations characteristic for this malignancy.4 Consistent with known significant genetic mutations that influence disease behavior, HGSOC is characterized by TP53 mutations in 96% of cases, whereas RB1 and PI3K/RAS pathways are deregulated in 67% and 45% of this type of EOC, respectively.4 Mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 are also characteristics of ovarian cancer and represent genes that participate in the homologous recombination pathway, which was found to be altered in 51% of HGSOC cases.4 Lastly, this study identified NOTCH and FOXM1 as signaling pathways that are frequently altered in HGSOC, with a 22% and 84% alteration frequency, respectively.

A clear understanding and classification of the particular set of genetic mutations that are prevalent in ovarian cancer holds premise for the preparation and testing of therapeutic drugs that target the genes and pathways important for cancer acquisition and maintenance. Unfortunately, interpretation of global genomic data is severely limited by tumor heterogeneity, high frequency of passenger mutations, and non-specific changes in gene expression in advanced cancers.5 It is becoming broadly accepted that cancers recapitulate the hierarchy of normal cell lineages and may exploit normal mechanisms involved in establishing and maintaining such hierarchic relationships to their advantage.6,7 Thus, understanding the cell of cancer origin may significantly facilitate our understanding of cancer pathogenesis. Alas, little is known about the ontogenesis of cell lineages of the female reproductive tract, including the existence and features of stem cell niches responsible for epithelial regeneration. This review aims to describe our current knowledge about putative cell types that may give rise to EOC and to outline the significance of stem cells and their niches in this process.

Views on the Cell of Origin of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

Traditionally, EOC was thought to originate mostly, if not exclusively, from the ovarian surface epithelium (OSE), a monolayer of flat to cuboidal cells surrounding the ovary and lining ovarian epithelial inclusions cysts that is formed as a result of cell entrapment after ovulation.8 The notion of EOC origination from the OSE or cysts is based on histopathological evidence9,10 and various experimental tests, such as transformation of OSE cells from rat,11,12 mouse,13 and human,14 the induction of EOC by OSE-targeted conditional genetic alterations in genetically modified mice,15-18 and by genetic analysis of human ovarian cystic inclusions.19 Notably, and consistent with similar patterns of genetic mutations observed in human and mouse EOC types, mouse neoplasms induced by Trp53 and Rb1 mutations histologically resemble HGSOC,15,18 whereas neoplasms associated with inactivation of Pten are classified as endometrioid carcinomas of the ovary.16,17

The hypothesis that the OSE serves as the source of ovarian cancer is consistent with observations of frequent rupture and repair of the OSE during ovulation, which provides plausible opportunities for genetic alterations that lead to carcinogenesis. Support for this hypothesis, often termed incessant ovulation, emerged from the observation that the risk of EOC decreases with fewer numbers of cycles as a result of pregnancy, lactation, and oral contraceptive pill use.1 Since OSE damage during ovulation leads to increased inflammation, the incessant ovulation theory also fits well with the concept of a causative role of inflammation in the origin of EOC.1 Hormonal stimulation, particularly by gonadotropin, may also contribute to EOC pathogenesis by promoting cell growth, increasing the mutation rate, and facilitating carcinogenesis.1,20 Albeit conceptually sound, these models and hypotheses do not define specific cancer-prone differentiation stages of the OSE cell lineage.

The broad variety of EOC phenotypes is usually attributed to the origin of the OSE from the coelomic epithelium, which also gives rise to the Müllerian (paramesonephric) ducts which, in turn, differentiate into the epithelia of the uterine tube (also called the oviduct, fallopian tube), endometrium, and endocervix.8 It has also been proposed that EOC may arise from components of the secondary Müllerian system.21 Moreover, based on morphological similarities of some HGSOCs to the epithelium of the uterine tubes, as well as findings of TP53 mutant atypical lesions (serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas [STICs]) in the epithelium of the uterine tube fimbria, it has been suggested that EOC can be derived from the tubal epithelium (TE).22 The ability of TE transformed in cell culture to form tumors reminiscent of EOC has been reported.23 In a further extension of this view, it has been speculated that some ovarian inclusion cysts may be the result of implantation by the uterine tube epithelium.24 Recently, it has been shown that transformation of the PAX8-expressing secretory TE cells by inactivation of Trp53, Brca1, and Pten leads to HGSOC in genetically modified mice.25 However, this study did not compare the relative transformation efficiency of either ciliated TE cells or OSE and did not test the role of RB pathway alterations in TE transformation. It was also reported that HGSOC might arise from the stroma of the uterine tube after anti-Müllerian hormone receptor type 2-Cre (Amhr2-Cre)–directed inactivation of Dicer and Pten in genetically modified mice.26 However, the relevance of these studies to human disease remains to be clarified because PTEN alterations are rare in human HGSOC.

In Search of Stem Cells of Ovarian Surface Epithelium and Tubal Epithelium

Adult stem cells are undifferentiated and long-lived cells compared to other cell types, and play functional roles in growth, repair, and homeostasis in the tissue that they reside in.27 Two defining characteristics of these adult stem cells are self-renewal and uni- or multipotency potential.28 In the self-renewal process, stem cells may undergo symmetric or asymmetric division to both maintain a defined stem cell population and create differentiated progeny. The multipotency characteristic of stem cells represents their ability to create heterogeneous differentiated progeny and thereby supply all the different cell types of the particular tissue that they are resident in. The cell turnover rate varies between different tissues and therefore the stem cells can either be proliferatively active or quiescent.28

The ovary is a reproductive organ and undergoes extensive tissue regeneration during the ovulatory process. The OSE is constantly involved in cell replacement of damaged and dead tissue at sites of ovulation. Interestingly, unlike many other epithelial tissues, the existence of stem cells for the OSE and TE has only recently begun to be addressed. A few years ago, using pulse-chase experiments with BrdU/IdU (5-bromo-2´-deoxyuridine/5-iodo-2´deoxyuridine) and tetracycline-regulated (doxycycline responsive) tetO-H2B-GFP transgenic mice, Szotek and colleagues29 showed the existence of ovarian epithelium label retaining cells (LRCs). This LRC population exhibits some properties of stem/progenitor cells, such as functional response to estrous cycling by proliferation in the mouse, enhanced colony forming ability in tissue culture, and the ability to exclude the DNA-binding dye Hoechst 33342.29 Another population of OSE cells was identified based on expression of the stem cell marker LY6A (also known as SCA1).30 Unfortunately, it remains uncertain whether these cells have potential for long-term self-renewal and contribute to OSE regeneration in vivo, key features of stem cells. Furthermore, it is unclear whether these cells occupy anatomically defined areas, similar to stem cells in other organs such as the intestine, hair follicle, cornea, and prostate.27,31

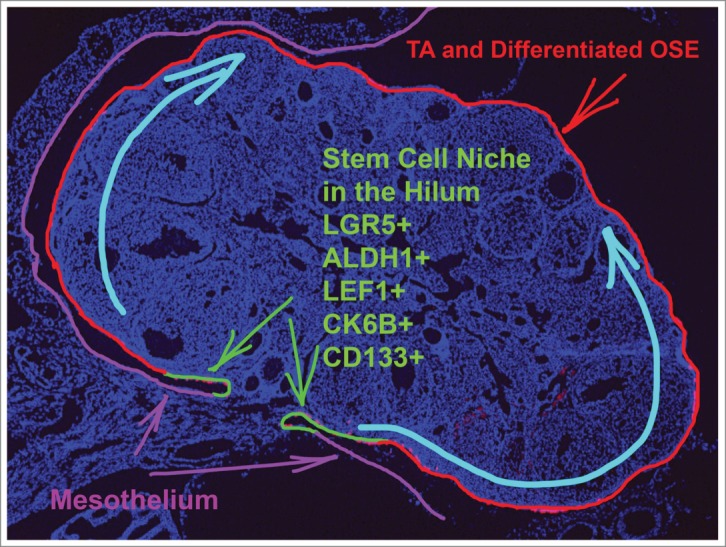

Recent reports identified the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) family of detoxifying enzymes as a useful marker of stem/progenitor cells in a number of cell lineages, including mammary, prostate, colon, hematopoietic, neural, and mesenchymal.32 Strikingly, the enzymatic activity of ALDH1 correlates well with its expression, thereby allowing assessment of ALDH1 function by conversion of ALDH substrate into the fluorescent product (ALDEFLUOR reaction), or by immunodetection techniques such as immunohistochemistry and western blotting.32 Using the ALDEFLUOR assay we were able to identify a pool of OSE cells with functional properties of stem/progenitor cells. In addition to expressing ALDH1 and the other stem cell markers CD133 and CK6B, this population expresses LGR5 and LEF1, components of canonical WNT pathways.33 The canonical WNT pathway is involved in a number of stem cell-related functions, including the maintenance, fate determination, and proliferation of stem cells.34 Furthermore, OSE-stem/progenitor cells show low expression levels of microRNAs of the miR-34 family (miR-34a, b, and c), which negatively regulate stem cell properties of adult stem cells.35 This subset of cells also exhibit self-renewal properties in clonogenic OSE sphere forming assays, contain slowly cycling cells in label retention assays, and contribute to OSE regeneration according to long-term lineage tracing experiments in vivo (Fig. 1 and33). Similar results confirming the location of Lgr5+ cells in the OSE of the hilum area were recently reported by the Barker group.36 However, these investigators also observed the presence of some Lgr5+ cells in highly proliferative areas around the ovary. This discrepancy might be explained by the high levels of Lgr5-eGFP-IRES-CreERT2 expression in their model. Consistent with these findings, we have observed that increased administration of tamoxifen allows labeling of some proliferating OSE cells around the ovary (Fu et al., in preparation).

Figure 1.

Stem cell niche of the ovarian surface epithelium. Progeny of the stem cells substitute for ovarian surface epithelium (OSE) that is dislodged during ovulation. TA, transit-amplifying cells.

Very little is known about stem cells for TE. It has been recently reported that LRCs are preferentially located in the distal end of the uterine tube in the mouse.37,38 Consistent with these findings, human TE contains a population of CD49f+CD44+ cells that preferentially localize in the distal end of the uterine tube and form monoclonal spheres in Matrigel.39 Expansion of these cells was detected in tubal intraepithelial carcinomas and in the uterine tubes from patients with invasive serous cancer. Unfortunately, little is known about the participation of these cells in regeneration of the TE in vivo. Their specific location in relation to the junction area between the TE and mesothelium and their gene expression profiles also remain unknown. Furthermore, given that not all stem/progenitor cells are quiescent,40 the label retention assay may not be sufficient for accurate identification and characterization of all stem cell niches. Most recently, it has been reported that embryonic and neonate Lgr5+ cells contribute to development of the epithelium of uterine tube fimbria.36 However, these cells do not contribute to regeneration of adult TE.33,36

Stem Cells and Cancer

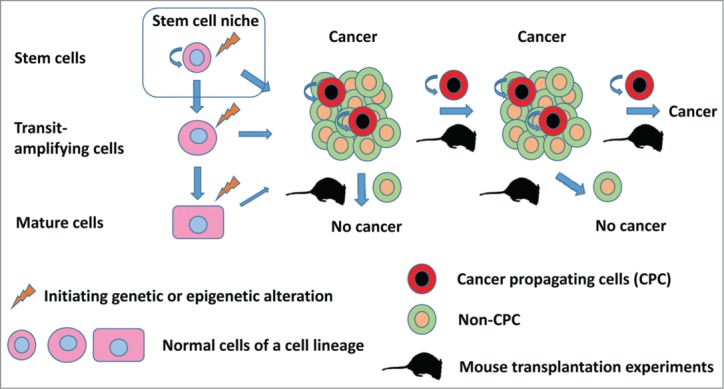

Carcinogenesis involves clonal competition of evolving neoplastic clones that are selected according to their fitness to a particular stage of malignant progression. This process is notable for the combination of partially preserved hierarchical structure typical of normal cell lineages with tumor heterogeneity reflecting continuous genetic and epigenetic flux that affects critical signal transduction networks. Mechanisms critical for tissue homeostasis, including the regulation of stem/progenitor cells, are frequently affected in cancer, resulting in the appearance of so-called “stemness” features.6,7 Such features can include the appearance of highly tumorigenic cancer cells that have stem-cell like properties, such as the ability to self-renew and recreate the complexity of the original tumors.41,42 Such cells can arise from either adult stem/progenitor cells33,35 or from more differentiated cells.43,44 Thus, although the term “cancer stem cells” has acquired a broad usage, it is somewhat misleading. The same is true for the term “cancer-initiating cells,” which may imply that such cells have been transformed by cancer initiating mutations whereas in reality transplantation of cancer-derived cells into the host results in propagation of already initiated cancer cells. Therefore, to avoid confusion we prefer to use the term “cancer propagating cells” (CPCs, Fig. 2). CPCs frequently show increased chemoresistance and therefore may play a significant role in cancer recurrence.6,7

Figure 2.

Schematic of the hierarchic relationship of normal and neoplastic cells. Cancer propagating cells (CPCs) represent a tumorigenic pool of cells with properties similar to those of normal stem cells, such as the ability to self-renew and produce non-tumorigenic or less tumorigenic progeny. However, CPCs do not necessarily arise from stem cells or represent cells that are targeted by initiating carcinogenic events, as the terms “cancer stem cells” and “cancer-initiating cells” may imply.

During recent years it has become increasingly clear that, similar to cancers of other locations, neoplastic cells in EOC may acquire molecular and cellular mechanisms typical of stem/progenitor cells.32,42,45,46 Of interest, we have shown that ovarian CPCs express ALDH1 and CD133,32,45,47 the markers expressed in normal OSE stem/progenitor cells.33 Furthermore, alterations in the WNT pathway and miR-34 inactivation are frequently detected in EOC.48-50 Given the cell lineage specificity of WNT and miR-34 signaling effects, further studies will be necessary to determine their roles in the functions of OSE stem/progenitor cells.

Cancer-Prone Stem Cell Niches

Stem cells require a protective microenvironment known as the stem cell niche. Niche components nurture the stem cells and shield them from unwanted stimuli, and/or initiate their differentiation as required.27,51 Anatomical niche locations have been defined for several organs. For example, a narrow transitional zone between the cornea and the bulbar conjunctiva called the limbus region shelters corneal epithelial stem cells,52,53 putative intestinal stem cells are located in a narrow band near the base of the intestinal crypt,54 and the hair-follicle bulge serves as a niche for hair follicle epidermal stem cells.55 These examples demonstrate preferred niche locations for different tissue structures. However, notably, all are closely located to nerves and vessels, elementary components that support stem cell nourishment.

Based on findings of shared immunohistochemical markers it has recently been proposed that parts of human OSE, TE, and adjacent mesothelium of extraovarian serosa may represent a transitional zone.8,56 Consistent with this hypothesis, transitional/junction regions have been identified between the mesothelium and tubal and ovarian epithelium.57,58 It has been further proposed that cells in the transitional/junction areas may have a more plastic, and presumably less differentiated, state, thereby being a possible place of origin of EOC.8,56 It is well known that many transitional/junction areas, such as the gastroesophageal, anal canal, uterine cervical, and corneal limbus junctions, are highly susceptible to cancer.59-63 The presence of adult stem cells in such junctions has been definitively demonstrated for the corneal limbus region52,53 and the gastroesophageal junction (64-66 and Table 1). Putative stem/progenitor cells have been identified in the anal canal67 and the uterine cervix.68 However, none of these studies provided definitive proof that stem/progenitor cells are more susceptible to malignant transformation than their more differentiated progeny.

Table 1.

Examples of putative cancer-prone stem cell niches in transitional zones

| Organ; species | Anatomical location | Assays | Niche markers | Cell types | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anus; Mouse | Anorectal junction | Label retention, IHC | CD34, integrin α6, Sox2, p63, Tenascin C | Simple columnar/stratified squamous epithelium cells | 67 |

| Eye (Cornea); Human, Mouse | Limbus | Histology, IHC, transplantation; wounding | ABCG2, CK14, p63 p63 | Limbal epithelium cells, Limbal basal epithelium cells | 79,80 |

| Ovary; Mouse | Hilum | FACS, label retention, lineage-tracing, sphere/clonal formation, gene-expression arrays, IHC, qRT-PCR, laser microdissection, transplantation | ALDH1, Lgr5, Lef1, CD133, CK6B | Ovarian surface epithelium cells | 33 |

| Stomach; Human, Mouse | Gastroesophageal junction | Histology, IHC, label retention, chemical random mutagenesis, lineage-tracing | Lgr5 | Epithelial base cells of pyloric gastric units | 64,65 |

| Uterine cervix; Human | Squamo-columnar junction | Gene-expression arrays, histology, IHC, western blotting | AGR2, CD63, GDA, CK7, MMP7 | Squamous/columnar epithelium cells | 68 |

Abbreviations: IHC, immunohistochemistry; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

In our recent study we demonstrated that OSE stem/progenitor cells predominantly reside in the hilum region of the ovary.33 Similar to other stem cell compartments, this region lies adjacent to nerves and vessels. Furthermore, the hilum encompasses the transitional/junction zone between OSE, mesothelium, and TE. In 1932, Butcher et al.69 reported that the greatest growth activity of OSE (or germinal epithelium) induced by ovulation occurred near the hilum of the rat ovary. Increased OSE proliferation was also observed in the hilum region of mice and rats after estrogen administration.70 It was also reported that the extent of OSE proliferation around the ovary was insufficient for post-ovulatory regeneration of OSE in adult mice.71 Consistent with this observation, it has been proposed that the OSE/mesothelium cells of the hilum might be responsible for providing additional cells for closure of ovulatory wounds.71,72 Interestingly, it has been also reported that the OSE at the hilum appears earlier than that in the rest of the bovine ovary.73 Although none of these reports proposed the existence of stem cell compartment in the hilum, their findings are consistent with our results showing that cells with stem cell properties reside in this region. Given the well-defined anatomical location of the hilum in the mouse ovary, identification of this region as a novel stem cell niche may represent an attractive model for studies of crosstalk between epithelial and stromal components, particularly in the context of junctions between OSE, mesothelium, and TE.

Our discovery of the stem cell compartment for OSE has provided a unique opportunity to test whether EOC arises from this compartment. To this end, we have inactivated Trp53 and Rb1 in isolated OSE stem/progenitor cells.33 Compared to their more differentiated progeny, hilum cells mutant for Trp53 and Rb1 exhibited increased proliferation and did not undergo senescence in cell culture. Furthermore, intraperitoneal transplantation of such cells into mouse resulted in the formation of metastatic carcinomas morphologically similar to human HGSOC. These findings provide direct experimental evidence that stem/progenitor cells located at the transitional/junction area have increased transformation potential and may result in HGSOC formation after inactivation of Trp53 and Rb1.

Future Directions and Challenges

Stem cell niches for epithelia of the reproductive system and their relevance to cancer pathogenesis remain poorly elucidated. Our recent studies have shown the existence of a cancer-prone stem cell niche for the OSE. Since previous studies of OSE stem cells have been based on the mouse model, identification of a similar niche in humans is one of the most urgent priorities. It will be also of particular interest to establish mechanisms controlling the OSE stem cell niche. Although the microenvironment plays a crucial role in the control of stem cell niches, some adult stem cells such as intestinal stem cells are fully self-organizing in tissue culture systems, indicating they are not entirely niche dependent40 Further studies should lead to an understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that regulate normal OSE regeneration and may also significantly accelerate our understanding of how aberrations in those regulatory mechanisms contribute to EOC pathogenesis. Furthermore, systematic analysis of the networks responsible for stem cell niche maintenance may lead to identification of novel serum EOC markers.

Notably, the cancer-prone OSE stem cell niche is located at the OSE junction with other epithelia. This anatomically defined location may allow a directed search for early neoplastic/precursor lesions by high-resolution imaging approaches, such as multiphoton laparoscopy/endoscopy74 Considering that ovarian cancer can be successfully treated if diagnosed at an early stage, clarification of the EOC place of origin is of particular importance.

The existence of TE stem cells remains insufficiently established. Further studies of putative TE stem/progenitor cells should establish their role in the regeneration of TE and their susceptibility to malignant transformation. Furthermore, it will be of interest to determine whether the cancer-prone TE stem cell niche is also located at the transitional/junction areas between TE and mesothelium.

Recently, it has become clear that a number of organs, such as intestine, prostate, and mammary gland, contain several stem cell pools that may compensate for each other under certain conditions, such as depletion of stem cell niche, inflammation, or wound healing.40,75,76 Thus, the search for additional OSE stem cell pools is warranted. Furthermore, recent studies of cell fate based on in vivo tracing have shown that the potential of stem cells for differentiation toward specific cell types may be far more limited than originally expected from cell transplantation studies. For example, transplanted prostate stem cells are able to differentiate into all 3 main cell types—basal, luminal and neuroendocrine—after their transplantation under the kidney capsule.77 However, basal and luminal lineages are maintained independently in adult animals.75,78 The development of approaches to trace cell fate under physiological conditions should be among the main priorities in the characterization of stem cell niches for the female reproductive tract.

On a more general note, further studies of cancer-prone stem niches may reinforce the need for a more focused search for stem cell niches at junction/transitional areas in other organs. Recent findings suggest that junction areas in other organs, such as the uterine cervix, anus, and esophagus, may also contain cancer-prone stem cell niches, thereby explaining the susceptibility of these organs to malignant transformation. Thus, future work may open a new field of research aimed at understanding why some stem cell populations reside in transitional/junction areas and how such a location contributes to cancer pathogenesis.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to our colleagues for the inability to include all relevant studies due to space limitations.

Funding

This work has been supported by NIH (CA096823) and NYSTEM (C028125 and C024174) grants to AYN.

References

- 1. Landen CN, Jr., Birrer MJ, Sood AK. Early events in the pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:995-1005; PMID:18195328; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64:9-29; PMID:24399786; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3322/caac.21208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cho KR, Shih Ie M. Ovarian cancer. Annu Rev Pathol 2009; 4:287-313; PMID:18842102; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Network TCGAR . Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 2011; 474:609-15; PMID:21720365; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr., Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013; 339:1546-58; PMID:23539594; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1235122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell 2014; 14:275-91; PMID: 24607403; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells: current status and evolving complexities. Cell Stem Cell 2012; 10:717-28; PMID:22704512; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Auersperg N, Woo MM, Gilks CB. The origin of ovarian carcinomas: a developmental view. Gynecol Oncol 2008; 110:452-4; PMID:18603285; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scully RE, Young RH, Clement PB. Tumors of the ovary, maldeveloped gonads, fallopian tube, and broad ligament. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Auersperg N. Culture and characterization of human ovarian surface epithelium. In: Bertlett JMS, ed. Ovarian Cancer: Methods and Protocols. New York: Humana Press; 2000; 169-73. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Godwin AK, Testa JR, Handel LM, Liu Z, Vanderveer LA, Tracey PA, Hamilton TC. Spontaneous transformation of rat ovarian surface epithelial cells: association with cytogenetic changes and implications of repeated ovulation in the etiology of ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1992; 84:592-601; PMID:1556770; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jnci/84.8.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Testa JR, Getts LA, Salazar H, Liu Z, Handel LM, Godwin AK, Hamilton TC. Spontaneous transformation of rat ovarian surface epithelial cells results in well to poorly differentiated tumors with a parallel range of cytogenetic complexity. Cancer Res 1994; 54:2778-84; PMID:8168110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Orsulic S, Li Y, Soslow RA, Vitale-Cross LA, Gutkind JS, Varmus HE. Induction of ovarian cancer by defined multiple genetic changes in a mouse model system. Cancer Cell 2002; 1:53-62; PMID:12086888; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1535-6108(01)00002-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dyck HG, Hamilton TC, Godwin AK, Lynch HT, Maines-Bandiera S, Auersperg N. Autonomy of the epithelial phenotype in human ovarian surface epithelium: changes with neoplastic progression and with a family history of ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer 1996; 69:429-36; PMID:8980241; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961220)69:6<429::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flesken-Nikitin A, Choi KC, Eng JP, Shmidt EN, Nikitin AY. Induction of carcinogenesis by concurrent inactivation of p53 and Rb1 in the mouse ovarian surface epithelium. Cancer Res 2003; 63:3459-63; PMID:12839925 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dinulescu DM, Ince TA, Quade BJ, Shafer SA, Crowley D, Jacks T. Role of K-ras and Pten in the development of mouse models of endometriosis and endometrioid ovarian cancer. Nat Med 2005; 11:63-70; PMID:15619626; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu R, Hendrix-Lucas N, Kuick R, Zhai Y, Schwartz DR, Akyol A, Hanash S, Misek DE, Katabuchi H, Williams BO, et al. Mouse model of human ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma based on somatic defects in the Wnt/beta-catenin and PI3K/Pten signaling pathways. Cancer Cell 2007; 11:321-33; PMID:17418409; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Szabova L, Yin C, Bupp S, Guerin TM, Schlomer JJ, Householder DB, Baran ML, Yi M, Song Y, Sun W, et al. Perturbation of Rb, p53, and Brca1 or Brca2 cooperate in inducing metastatic serous epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 2012; 72:4141-53; PMID:22617326; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pothuri B, Leitao MM, Levine DA, Viale A, Olshen AB, Arroyo C, Bogomolniy F, Olvera N, Lin O, Soslow RA, et al. Genetic analysis of the early natural history of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. PLoS One 2010; 5:e10358; PMID:20436685; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0010358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Auersperg N, Wong AS, Choi KC, Kang SK, Leung PC. Ovarian surface epithelium: biology, endocrinology, and pathology. Endocr Rev 2001; 22:255-88; PMID:11294827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dubeau L. The cell of origin of ovarian epithelial tumours. Lancet Oncol 2008; 9:1191-7; PMID: 19038766; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70308-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Medeiros F, Muto MG, Lee Y, Elvin JA, Callahan MJ, Feltmate C, Garber JE, Cramer DW, Crum CP. The tubal fimbria is a preferred site for early adenocarcinoma in women with familial ovarian cancer syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30:230-6; PMID:16434898; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/01.pas.0000180854.28831.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karst AM, Levanon K, Drapkin R. Modeling high-grade serous ovarian carcinogenesis from the fallopian tube. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:7547-52; PMID:21502498; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1017300108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kurman RJ, Shih Ie M. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34:433-43; PMID:20154587; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf3d79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Perets R, Wyant GA, Muto KW, Bijron JG, Poole BB, Chin KT, Chen JY, Ohman AW, Stepule CD, Kwak S, et al. Transformation of the fallopian tube secretory epithelium leads to high-grade serous ovarian cancer in Brca;Tp53;Pten models. Cancer Cell 2013; 24:751-65; PMID:24332043; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim J, Coffey DM, Creighton CJ, Yu Z, Hawkins SM, Matzuk MM. High-grade serous ovarian cancer arises from fallopian tube in a mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:3921-6; PMID:22331912; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1117135109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hsu YC, Fuchs E. A family business: stem cell progeny join the niche to regulate homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012; 13:103-14; PMID:22266760; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm3272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Snippert HJ, Clevers H. Tracking adult stem cells. EMBO Rep 2011; 12:113-22; PMID:21252944; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/embor.2010.216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Szotek PP, Chang HL, Brennand K, Fujino A, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Lo Celso C, Dombkowski D, Preffer F, Cohen KS, Teixeira J, et al. Normal ovarian surface epithelial label-retaining cells exhibit stem/progenitor cell characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:12469-73; PMID:18711140; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0805012105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gamwell LF, Collins O, Vanderhyden BC. The mouse ovarian surface epithelium contains a population of LY6A (SCA-1) expressing progenitor cells that are regulated by ovulation-associated factors. Biol Reprod 2012; 87:80; PMID:22914315; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1095/biolreprod.112.100347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nikitin AY, Nafus MG, Zhou Z, Liao C-P, Roy-Burman P. Prostate stem cells and cancer in animals. In: Bagley RG, Teicher BA, eds. Stem Cells and Cancer. New York: Humana Press; 2009; 199-216. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deng S, Yang X, Lassus H, Liang S, Kaur S, Ye Q, Li C, Wang LP, Roby KF, Orsulic S, et al. Distinct expression levels and patterns of stem cell marker, aldehyde dehydrogenase isoform 1 (ALDH1), in human epithelial cancers. PLoS One 2010; 5:e10277; PMID:20422001; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0010277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Flesken-Nikitin A, Hwang CI, Cheng CY, Michurina TV, Enikolopov G, Nikitin AY. Ovarian surface epithelium at the junction area contains a cancer-prone stem cell niche. Nature 2013; 495:241-5; PMID:23467088; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature11979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 2012; 149:1192-205; PMID:22682243; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cheng CY, Hwang CI, Corney DC, Flesken-Nikitin A, Jiang L, Oner GM, Munroe RJ, Schimenti JC, Hermeking H, Nikitin AY. miR-34 cooperates with p53 in suppression of prostate cancer by joint regulation of stem cell compartment. Cell Rep 2014; 6:1000-7; PMID:24630988; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ng A, Tan S, Singh G, Rizk P, Swathi Y, Tan TZ, Huang RY, Leushacke M, Barker N. Lgr5 marks stem/progenitor cells in ovary and tubal epithelia. Nat Cell Biol 2014; 16:745-57; PMID:24997521; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb3000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang Y, Sacchetti A, van Dijk MR, van der Zee M, van der Horst PH, Joosten R, Burger CW, Grootegoed JA, Blok LJ, Fodde R. Identification of quiescent, stem-like cells in the distal female reproductive tract. PLoS One 2012; 7:e40691; PMID:22848396; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0040691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Patterson AL, Pru JK. Long-term label retaining cells localize to distinct regions within the female reproductive epithelium. Cell Cycle 2013; 12:2888-98; PMID:24018418; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.25917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Paik DY, Janzen DM, Schafenacker AM, Velasco VS, Shung MS, Cheng D, Huang J, Witte ON, Memarzadeh S. Stem-like epithelial cells are concentrated in the distal end of the fallopian tube: a site for injury and serous cancer initiation. Stem Cells 2012; 30:2487-97; PMID:22911892; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/stem.1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Clevers H. The intestinal crypt, a prototype stem cell compartment. Cell 2013; 154:274-84; PMID:23870119; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wicha MS, Liu S, Dontu G. Cancer stem cells: an old idea–a paradigm shift. Cancer Res 2006; 66:1883-90; PMID:16488983; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cheng L, Ramesh AV, Flesken-Nikitin A, Choi J, Nikitin AY. Mouse models for cancer stem cell research. Toxicol Pathol 2010; 38:62-71; PMID:19920280; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/0192623309354109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Friedmann-Morvinski D, Bushong EA, Ke E, Soda Y, Marumoto T, Singer O, Ellisman MH, Verma IM. Dedifferentiation of neurons and astrocytes by oncogenes can induce gliomas in mice. Science 2012; 338:1080-4; PMID:23087000; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1226929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schwitalla S, Fingerle AA, Cammareri P, Nebelsiek T, Goktuna SI, Ziegler PK, Canli O, Heijmans J, Huels DJ, Moreaux G, et al. Intestinal tumorigenesis initiated by dedifferentiation and acquisition of stem-cell-like properties. Cell 2013; 152:25-38; PMID:23273993; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alvero AB, Chen R, Fu HH, Montagna M, Schwartz PE, Rutherford T, Silasi DA, Steffensen KD, Waldstrom M, Visintin I, et al. Molecular phenotyping of human ovarian cancer stem cells unravels the mechanisms for repair and chemoresistance. Cell Cycle 2009; 8:158-66; PMID:19158483; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.8.1.7533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wei X, Dombkowski D, Meirelles K, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Szotek PP, Chang HL, Preffer FI, Mueller PR, Teixeira J, MacLaughlin DT, et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance preferentially inhibits stem/progenitors in human ovarian cancer cell lines compared with chemotherapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:18874-9; PMID:20952655; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1012667107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ferrandina G, Martinelli E, Petrillo M, Prisco MG, Zannoni G, Sioletic S, Scambia G. CD133 antigen expression in ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 2009; 9:221; PMID:19583859; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2407-9-221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bitler BG, Nicodemus JP, Li H, Cai Q, Wu H, Hua X, Li T, Birrer MJ, Godwin AK, Cairns P, et al. Wnt5a suppresses epithelial ovarian cancer by promoting cellular senescence. Cancer Res 2011; 71:6184-94; PMID:21816908; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schmid S, Bieber M, Zhang F, Zhang M, He B, Jablons D, Teng NN. Wnt and hedgehog gene pathway expression in serous ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2011; 21:975-80; PMID:21666490; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821caa6f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Corney DC, Hwang CI, Matoso A, Vogt M, Flesken-Nikitin A, Godwin AK, Kamat AA, Sood AK, Ellenson LH, Hermeking H, et al. Frequent downregulation of miR-34 family in human ovarian cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16:1119-28; PMID:20145172; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Blanpain C, Fuchs E. Stem cell plasticity. Plasticity of epithelial stem cells in tissue regeneration. Science 2014; 344:1242281; PMID:24926024; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1242281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schermer A, Galvin S, Sun TT. Differentiation-related expression of a major 64K corneal keratin in vivo and in culture suggests limbal location of corneal epithelial stem cells. J Cell Biol 1986; 103:49-62; PMID:2424919; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.103.1.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pellegrini G, Golisano O, Paterna P, Lambiase A, Bonini S, Rama P, De Luca M. Location and clonal analysis of stem cells and their differentiated progeny in the human ocular surface. J Cell Biol 1999; 145:769-82; PMID:10330405; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.145.4.769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 2007; 449:1003-7; PMID:17934449; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Alonso L, Fuchs E. Stem cells of the skin epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100 (Suppl 1):11830-5; PMID:12913119; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1734203100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Auersperg N. The origin of ovarian carcinomas: a unifying hypothesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2011; 30:12-21; PMID:21131839; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181f45f3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Seidman JD, Yemelyanova A, Zaino RJ, Kurman RJ. The fallopian tube-peritoneal junction: a potential site of carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2011; 30:4-11; PMID:21131840; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181f29d2a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nicosia SV, Johnson JH. Surface morphology of ovarian mesothelium (surface epithelium) and of other pelvic and extrapelvic mesothelial sites in the rabbit. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1984; 3:249-60; PMID:6500800; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00004347-198403000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McNairn AJ, Guasch G. Epithelial transition zones: merging microenvironments, niches, and cellular transformation. Eur J Dermatol 2011; 21(Suppl 2):21-8; PMID:2162812611815342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. McKelvie PA, Daniell M, McNab A, Loughnan M, Santamaria JD. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: a series of 26 cases. Br J Ophthalmol 2002; 86:168-73; PMID:11815342; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/bjo.86.2.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Waring GO, 3rd, Roth AM, Ekins MB. Clinical and pathologic description of 17 cases of corneal intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Ophthalmol 1984; 97:547-59; PMID:6720832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fluhmann CF. Carcinoma in situ and the transitional zone of the cervix uteri. Obstet Gynecol 1960; 16:424-37; PMID:13700408 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Petignat P, Roy M. Diagnosis and management of cervical cancer. BMJ 2007; 335:765-8; PMID:17932207; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/bmj.39337.615197.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, van de Wetering M, Snippert HJ, van Es JH, Sato T, Stange DE, Begthel H, van den Born M, et al. Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell 2010; 6:25-36; PMID: 20085740; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Trudgill NJ, Suvarna SK, Royds JA, Riley SA. Cell cycle regulation in patients with intestinal metaplasia at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Mol Pathol 2003; 56:313-7; PMID:14645692; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/mp.56.6.313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Odze RD. Pathology of the gastroesophageal junction. Semin Diagn Pathol 2005; 22:256-65; PMID:16939053; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1053/j.semdp.2006.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Runck LA, Kramer M, Ciraolo G, Lewis AG, Guasch G. Identification of epithelial label-retaining cells at the transition between the anal canal and the rectum in mice. Cell Cycle 2010; 9:3039-45; PMID:20647777; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.9.15.12437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Herfs M, Yamamoto Y, Laury A, Wang X, Nucci MR, McLaughlin-Drubin ME, Munger K, Feldman S, McKeon FD, Xian W, et al. A discrete population of squamocolumnar junction cells implicated in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:10516-21; PMID:22689991; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1202684109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Butcher EO, College H. The effect of many corpora lutea on germ-cell formation and growth in the ovary of the white rat. Anat Rec 1932; 54:1; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ar.1090540109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Stein KF, Allen E. Attempts to stimulate proliferation of the germinal epithelium of the ovary. Anat Rec 1942; 82. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tan OL, Fleming JS. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen immunoreactivity in the ovarian surface epithelium of mice of varying ages and total lifetime ovulation number following ovulation. Biol Reprod 2004; 71:1501-7; PMID:15229142; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Beller U, Haimovitch R, Ben-Sasson S. Periovulatory multifocal mesothelial proliferation: a possible association with malignant transformation. Int J Gynecol Cancer 1995; 5:306-9; PMID:11578495; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1525-1438.1995.05040306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hummitzsch K, Irving-Rodgers HF, Hatzirodos N, Bonner W, Sabatier L, Reinhardt DP, Sado Y, Ninomiya Y, Wilhelm D, Rodgers RJ. A new model of development of the mammalian ovary and follicles. PLoS One 2013; 8:e55578; PMID:23409002; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0055578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Williams RM, Flesken-Nikitin A, Ellenson LH, Connolly DC, Hamilton TC, Nikitin AY, Zipfel WR. Strategies for high-resolution imaging of epithelial ovarian cancer by laparoscopic nonlinear microscopy. Transl Oncol 2010; 3:181-94; PMID:20563260; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1593/tlo.09310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Choi N, Zhang B, Zhang L, Ittmann M, Xin L. Adult murine prostate basal and luminal cells are self-sustained lineages that can both serve as targets for prostate cancer initiation. Cancer Cell 2012; 21:253-65; PMID:22340597; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Van Keymeulen A, Rocha AS, Ousset M, Beck B, Bouvencourt G, Rock J, Sharma N, Dekoninck S, Blanpain C. Distinct stem cells contribute to mammary gland development and maintenance. Nature 2011; 479:189-93; PMID:21983963; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Leong KG, Wang BE, Johnson L, Gao WQ. Generation of a prostate from a single adult stem cell. Nature 2008; 456:804-8; PMID:18946470; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature07427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, Dawlaty MM, Cheng AW, Zhang F, Jaenisch R. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell 2013; 153:910-8; PMID:23643243; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rama P, Matuska S, Paganoni G, Spinelli A, De Luca M, Pellegrini G. Limbal stem-cell therapy and long-term corneal regeneration. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:147-55; PMID:20573916; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0905955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lin Z, He H, Zhou T, Liu X, Wang Y, He H, Wu H, Liu Z. A mouse model of limbal stem cell deficiency induced by topical medication with the preservative benzalkonium chloride. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013; 54:6314-25; PMID:23963168; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1167/iovs.12-10725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]