Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are defined as RNA transcripts larger than 200 nucleotides that do not appear to have protein-coding potential. Accumulating evidence indicates that lncRNAs are involved in tumorigenesis. Our work reveals that lncRNA FAL1 (focally amplified lncRNA on chromosome 1) is frequently and focally amplified in human cancers and mediates oncogenic functions.

Keywords: long noncoding RNA, somatic copy number alterations, cancer

Somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) are frequently found in cancers as a result of the highly unstable and disorganized status of the cancer genome. Normally, SCNA leads to changes in expression levels of the genes encoded by the SCNA loci; depending on gain or loss of the copy number, gene expression level is increased or decreased, respectively. SCNA is therefore an important mechanism of dysregulated gene expression in cancer cells. Previous work demonstrated that SCNA is not only a passenger during tumor development, but that a subset of SCNAs also contribute to tumorigenesis.1,2 By integrating data of large-scale genomic profiling and functional genome-wide screening, scientists have identified many crucial regulators of tumorigenesis encoded by SCNA loci, including protein-coding genes and small regulatory RNA genes such as miRNAs.

Recent research indicated that the majority of the human genome gives rise to a large number of noncoding transcripts. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are defined as RNA transcripts that are larger than 200 nucleotides but do not appear to have protein-coding potential. LncRNAs are involved in a wide range of biological processes, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, immune response, and apoptosis, and function through various mechanisms, including acting as scaffolds or guides for protein–protein or protein–chromatin interaction, as enhancers to affect gene transcription, and as decoys to bind proteins or miRNAs.3-8 LncRNA expression is highly cell type and tissue specific. Like protein-coding genes, the regulation of lncRNA transcription is subjected to canonical histone modification-mediated control. However, to date few studies on SCNAs of lncRNAs and their potential roles in tumorigenesis have been performed.

In our recent study, to characterize the landscape of lncRNA gene SCNAs across cancers we conducted a genome-wide survey of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray data in 2,394 tumor specimens from 12 cancer types.9 We analyzed SCNAs of 13,870 lncRNAs, whose genomic location were retrieved from the GENCODE Consortium. Across the 12 tumor types, we found a high frequency (more than 25% specimens of a given type of tumor) of copy number gain and loss in an average of 12.0% and 7.6% of lncRNAs, respectively. Additionally, lncRNA SCNA profiles were tumor type specific. These results implied that a large number of lncRNA SCNAs might play specific roles in different cancer types. To narrow down the candidates for tumorigenic lncRNA genes and gain an insight of their functions in cancers, we applied 2 more selection criteria for the above lncRNAs with high frequency of copy number gain and loss: (1) the lncRNA is located in a focal amplicon; and (2) the RNA transcript of the candidate is detectable in more than 50% cancer cell lines (a total of 40 lines from the NCI60 cancer cell line panel). As a result, we finally focused on a candidate lncRNA named FAL1 (focally amplified lncRNA on chromosome 1).

Several functional experiments were conducted to characterize the oncogenic properties of FAL1. Knocking down FAL1 in cancer cell lines from different tumor types retarded their proliferation rates and led to cellular senescence. When combined with other well-known oncogenes, such as RAS (rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) and MYC (v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog), FAL1 dramatically enhanced the efficiency of malignant transformation in primary epithelial cells. Concordantly, FAL1 downregulation by siRNA delivery inhibited orthotopic tumor growth in a mouse ovarian cancer model. Furthermore, we found that expression and SCNA of FAL1 is associated with clinical outcomes in patients with ovarian cancer.

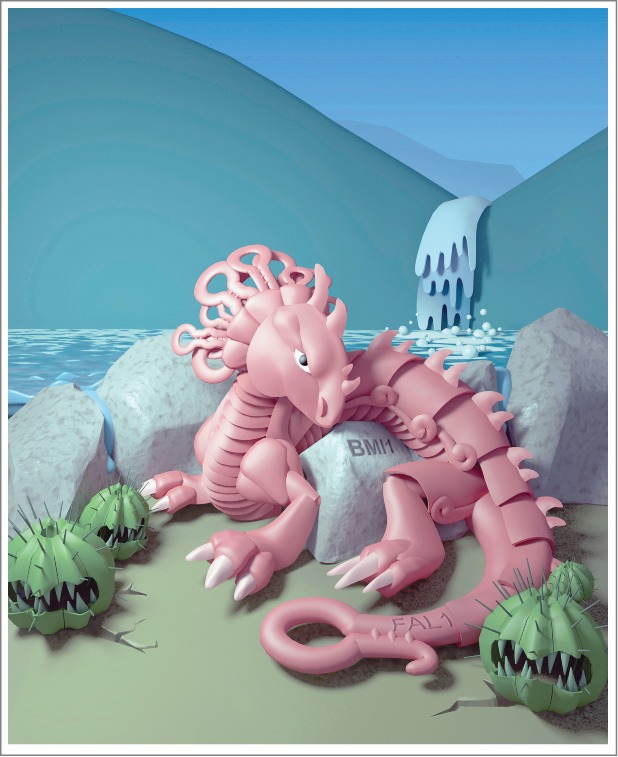

Since FAL1 displayed striking oncogenic activity in multiple functional experiments, it is intriguing to explore the underlying molecular mechanism. With this aim, we investigated proteins that associate with FAL1 using RNA pull-down technology. BMI1 (BMI1 proto-oncogene, polycomb ring finger), a core subunit of the polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1), was initially identified and validated as a FAL1-interacting partner. The association of FAL1 with BMI1 warranted further investigation because there is evidence that the interaction between lncRNAs and PRC1/2 represents one of the mechanisms by which lncRNAs modulate gene expression. For example, HOTAIR (HOX transcript antisense RNA) and ANRIL (CDKN2B antisense RNA 1) both associate with PRC subunits to regulate the transcription of multiple genes.4,10 Further studies indicated that FAL1–BMI1 association significantly enhanced BMI1 protein stability as well as the level of ubH2AK119, which is a product of histone modification by PRC1 and whose level in promoter regions directly affects gene expression in an epigenetic manner. Therefore, we further explored the profile of genes regulated by FAL1–BMI1 to help explain the oncogenic function of FAL1. Gene expression microarray analysis showed that knocking down FAL1 or BMI1 induced expression changes of a large set of target genes in common, which included genes involved in cell-cycle control and apoptosis such as CDKN1A (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A, best known as p21), FAS (Fas cell surface death receptor), BTG2 (BTG family, member 2), TP53I3 (tumor protein p53 inducible protein 3), FBXW7 (F-box and WD repeat domain containing 7, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase), and CYFIP2 (cytoplasmic FMR1 interacting protein 2). On the other hand, BMI1 protein was found to be associated with the promoter regions of these target genes dependent on the presence of FAL1. Among the common targets of FAL1 and BMI1, we focused on p21 because of its remarkable fold change in expression and its significant contribution to tumorigenesis. We further demonstrated that FAL1 regulated cell cycle progression and cellular senescence, as well as xenograft tumor growth in vivo, by suppressing p21 expression. This explained, at least in part, the mechanism underlying the oncogenic activity of FAL1 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Oncogenic long noncoding RNA FAL1 in human cancers. This schematic depicts the oncogenic lncRNA FAL1 (focally amplified lncRNA on chromosome 1; the dragon), which regulates gene transcription and promotes tumorigenesis. FAL1 stabilizes BMI1 (BMI1 proto-oncogene, polycomb ring finger; the stone) by associating with it (the dragon twines around the stone) and subsequently enhances the activity of PRC1 (polycomb repressive complex 1; the pile of stone). Constant information flow from DNA to mRNA (the water stream) is essential for normal cell growth. Inhibition of transcription (blockade of water) of tumor suppressor genes, such as p21 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A, best known as p21), leads to cell transformation (growth of the cactus-like eremophytes instead of normal plants). Artwork by Lili Guo.

It is believed that lncRNAs have great clinical potential as a class of cancer biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Our findings add a new player, FAL1, to this field. These data should aid the development of FAL1 as an informative biomarker for cancer, as well as its clinical application based on siRNA delivery targeting lncRNA FAL1 to treat cancer.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to scientists whose work was not discussed here due to space constraints.

Funding

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the One Hundred Person Project of Sun Yat-Sen University (XZ), National Natural Science Foundation 81302262 (XZ), the Basser Research Center for BRCA (LZ), the National Institutes of Health R01CA142776, R01CA190415, P50CA083638 (LZ), the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (LZ and XH), the Breast Cancer Alliance (LZ), Department of Defense (LZ), and the Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research (LZ).

References

- 1. Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, Barretina J, Boehm JS, Dobson J, Urashima M, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature 2010; 463:899-905; PMID:20164920; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature08822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zack TI, Schumacher SE, Carter SL, Cherniack AD, Saksena G, Tabak B, Lawrence MS, Zhang CZ, Wala J, Mermel CH, et al. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet 2013; 45:1134-40; PMID:24071852; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng.2760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, Tsai MC, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature 2010; 464:1071-6; PMID:20393566; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature08975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, Mosammaparast N, Wang JK, Lan F, Shi Y, Segal E, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science 2011; 329:689-93; PMID:20616235; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1192002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jeon Y, Lee JT. YY1 tethers Xist RNA to the inactive X nucleation center. Cell 2010; 146:119-33; PMID:21729784; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tripathi V, Ellis JD, Shen Z, Song DY, Pan Q, Watt AT, Freier SM, Bennett CF, Sharma A, Bubulya PA, et al. The nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation. Mol Cell 2010; 39:925-38; PMID:20797886; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Orom UA, Derrien T, Beringer M, Gumireddy K, Gardini A, Bussotti G, Lai F, Zytnicki M, Notredame C, Huang Q, et al. Long noncoding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells. Cell 2010; 143:46-58; PMID:20887892; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huarte M, Guttman M, Feldser D, Garber M, Koziol MJ, Kenzelmann-Broz D, Khalil AM, Zuk O, Amit I, Rabani M, et al. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell 2010; 142:409-19; PMID:20673990; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hu X, Feng Y, Zhang D, Zhao SD, Hu Z, Greshock J, Zhang Y, Yang L, Zhong X, Wang LP, et al. A Functional Genomic Approach Identifies FAL1 as an Oncogenic Long Noncoding RNA that Associates with BMI1 and Represses p21 Expression in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2014; 26:344-57; PMID:25203321; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yap KL, Li S, Munoz-Cabello AM, Raguz S, Zeng L, Mujtaba S, Gil J, Walsh MJ, Zhou MM. Molecular interplay of the noncoding RNA ANRIL and methylated histone H3 lysine 27 by polycomb CBX7 in transcriptional silencing of INK4a. Mol Cell 2010; 38:662-74; PMID:20541999; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]