ABSTRACT

The Ras-related protein Cell division cycle 42 (Cdc42) is important in cell-signaling processes. Protein interactions involving Cdc42 occur primarily in flexible “Switch” regions that help regulate effector binding. We studied the kinetics of intrinsic GTP hydrolysis reaction in the absence and presence of a biologically active peptide derivative of a p21-activated kinase effector (PBD46) for wt Cdc42 and compared it to the Switch 1 variant Cdc42(T35A). While the binding of PBD46 to wt Cdc42 results in complete inhibition of GTP hydrolysis, this interaction in Cdc42(T35A) does not. Comparison of the crystal structure of wt Cdc42 in the absence of effector (1AN0.pdb), as well as the NMR structure of wt Cdc42 bound to an effector in the Switch 1 region (1CF4.pdb) (www.rcsb.org) suggests that the orientation of T35 with bound Mg2+ changes in the presence of effector, resulting in movement of GTP away from the catalytic box leading to the inhibition of GTP hydrolysis. For Cdc42(T35A), molecular dynamics simulations and structural analyses suggest that the nucleotide does not undergo the conformational shift observed for the wt Cdc42-effector interaction. Our data suggest that change in dynamics in the Switch 1 region of Cdc42 caused by the T35A mutation (Chandrashekar, et al. 2011, Biochemistry, 50, p. 6196) fosters a conformation for this Cdc42 variant that allows hydrolysis of GTP in the presence of PBD46, and that alteration of the conformational dynamics could potentially modulate Ras-related over-activity.

KEYWORDS: cell division cycle 42 (Cdc42), GTP hydrolysis, protein dynamics, ras, switch 1 variant

Introduction

Approaches to block potentially oncogenic Ras-effector protein interactions could lead to more effective methods to regulate aberrant cell signaling. Cdc42, a member of the Ras family, has been an excellent protein model to probe structure-function relationships of cell-signaling processes mediating cell transformation.1-4 Cdc42, like most other Ras proteins, acts as a molecular switch between an active GTP-bound “On” state and an inactive GDP-bound “Off” state.2,3 Certain oncogenic variants of Ras are known to cause the loss of intrinsic and/or GAP-stimulated GTP hydrolysis, leading to over-activity from the “Locked” GTP-bound state.5 Furthermore, since concentrations of GTP in the cell are much higher than GDP, interactions with effectors that inhibit GTP hydrolysis could also result in over-activity.6 It has been suggested that the inactivation of oncogenic Ras protein activity might be achieved by using small molecules that could restore GTP hydrolysis in compromised Ras proteins that are unable to hydrolyze GTP.7 However, there has been concern that bound GTP might block the access of small-molecules to the nucleotide-binding site.7

Proper Ras function depends on a functionally invariant threonine residue in the Switch 1 region, a region known to bind to various effector/regulatory proteins in Ras-related proteins. Structural and dynamics studies of Ras and Cdc42 furthermore have outlined the highly flexible Switch 1 region (residues 28–40 where position 35 is occupied by a threonine) as being an important factor in the promiscuity of these GTPases for various effectors.6,8-10 Studies by Spoerner et al., using 31P-NMR data, suggested that wild type (wt) Ras exists in 2 conformations, with one of the conformations being able to interact strongly with effectors and one not able to.11 However, 31P-NMR data on a Ras variant in which threonine was substituted by alanine in Switch 1 (T35A) suggested that, under steady-state conditions, the protein exists predominantly in a single conformation. Moreover, no significant chemical shift changes were observed when effectors were added to the Switch 1 variant Ras(T35A), suggesting that no or subtle conformational change(s) accompany Ras(T35A)-effector interactions.11,12 In addition, Ras(T35A) exhibits a 12-fold decrease in binding affinity to a GAP effector compared to wt Ras, suggesting that the mutation causes a change in how Cdc42 interacts with its effectors.13

PBD46 is a 46-residue effector peptide derivative of p21-activated serine/threonine kinase (PAK) that inhibits Cdc42-stimulated intrinsic GTP hydrolysis. The interaction between Cdc42 and PBD46 has been characterized and found to occur in the highly flexible Switch 1 (residues 28–40) and Switch 2 (residues 57–74) regions of Cdc42.6,9,14,15 Switch 1 in particular has been shown to be involved in altered intrinsic GTPase activity, anti-apoptotic events, and modified interactions with regulatory proteins.16 In addition, based on NMR-derived chemical shift differences, the Switch regions become less dynamic when bound to PBD46.9 31P-NMR data furthermore show marked chemical shift perturbations for the bound nucleotide when comparing wt Cdc42 in the presence and absence of PBD46.17 However, 31P-NMR data for Cdc42(T35A) showed no clear peak shift changes upon binding of PBD46 to the mutant protein, while line broadening suggested that an interaction between PBD46 and Cdc42(T35A) is present, although weaker than in wt Cdc42.17 The conformational changes observed for wt Cdc42 upon binding to PBD46 are therefore not nearly as distinct for Cdc42(T35A) in the presence of the same effector. Similar observations have also applied for wt Ras versus Ras(T35A) in the presence of its effectors.11,12

Previous studies examining the oncogenic transformation in fibroblasts as well as neurite induction of PC12 cells suggested that p21Ras(T35A) is a non-oncogenic mutant of p21Ras.13 Further, it was shown that p21Ras(T35A) did not activate transformation in NIH 3T3 cells.18 However, the molecular details underlying these observations are unknown for this mutation. Recently, we investigated the importance of the conformational flexibility in the Switch 1 region of Cdc42 by determining the solution structure and characterizing the backbone dynamics of the Ras-related mutant Cdc42(T35A).19 Our study showed that the T35A mutation leads to changes in the internal motions for several of the Switch 1 residues leading to a loss of conformational flexibility in this region. The mutation also affects Cdc42s interaction with PBD46, similar to what was shown for p21Ras(T35A) and effectors as compared to wt p21Ras. 13 Here, we measure Cdc42(T35A)-stimulated intrinsic GTP hydrolysis in the absence and presence of PBD46 and compare it to that of wt Cdc42. Our results show that, when PBD46 is added, GTP hydrolysis still occurs in Cdc42(T35A), whereas it is completely inhibited in the wt. Analysis of our results highlight differences in the rates and efficiency of GTP hydrolysis in the presence of PBD46 for Cdc42(T35A) relative to unbound Cdc42(T35A). We have used molecular dynamics simulations to characterize the effects of the mutation that could lead to the restored GTP hydrolytic activity of Cdc42(T35A) in the presence of the effector. Analysis of structures of other Cdc42-effector interactions in combination with our molecular dynamics simulations suggest that, while the conformation of the wt Cdc42-PBD46 complex prevents the nucleotide from being oriented in the catalytic box for hydrolysis, for the Cdc42(T35A)-PBD46 complex, the nucleotide remains in a conformation/orientation that leaves it susceptible to hydrolysis. Overall, the data suggest that the changes in dynamics seen for Cdc42(T35A) might facilitate a conformation that allows GTP hydrolysis to proceed in the presence of PBD46. We discuss the implications of this work as it relates to the potential development of approaches to inactivate oncogenic Ras protein activity by modulating conformational and/or dynamics properties to block Ras protein interactions.

Results

Intrinsic GTP hydrolysis by wt Cdc42 vs. Cdc42(T35A) as a function of PBD46 concentration

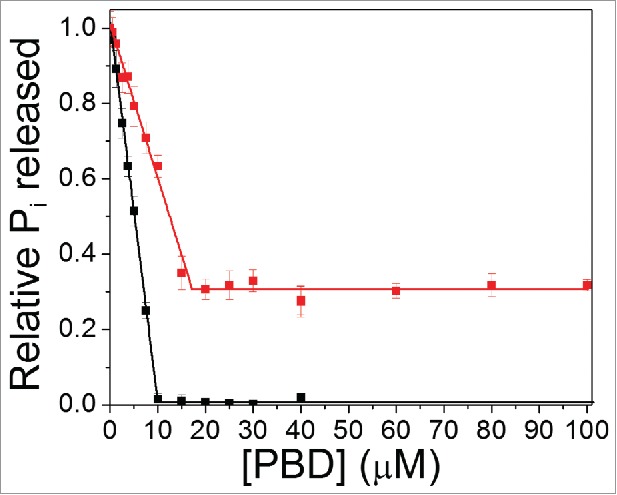

The goal of this study was to examine how a mutation in the Switch 1 region of Cdc42 affected its intrinsic GTP hydrolysis activity in the presence of a peptide derivative of p21-activated serine/threonine kinase, PBD46. The amount of inorganic phosphate (Pi) released from GTP in the presence of increasing concentrations of PBD46 bound to wt Cdc42 or Cdc42(T35A) was measured (Fig. 1). As PBD46 is added to wt Cdc42, there is a decrease in Pi released up to a concentration of 10 μM PBD46, at which point intrinsic GTP hydrolysis is totally inhibited. For Cdc42(T35A), the data in Figure 1 shows a decrease in PPi released up to a concentration of 15–17 μM PBD46, but that plateaus prior to reaching 0. This suggests that, for Cdc42(T35A), there is a conformational state in the presence of PBD46, which does not lead to the total inhibition of GTP hydrolysis as is shown for the wt-PBD46 interaction.

Figure 1.

Intrinsic GTP hydrolysis is observed for Cdc42(T35A) in the presence of PBD46. Plot of inorganic phosphate released (Pi) over 30 minutes stimulated by wt Cdc42 (Black line) relative to Cdc42T35A) (Red line) as a function of increasing PBD46 concentration.

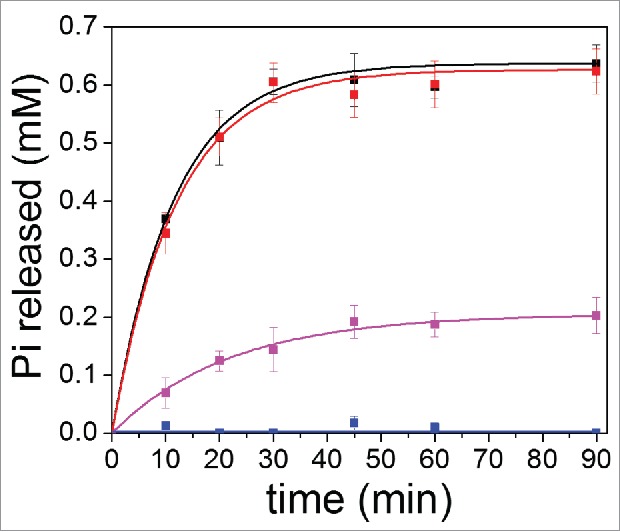

Measurement of GTP hydrolysis rates of wt Cdc42 and Cdc42(T35A) in the absence and presence of PBD46

The rates of GTP hydrolysis for wt Cdc42 and Cdc42(T35A) were compared by measuring the amount of Pi released as a function of time in the absence and presence of 30 μM PBD (Fig. 2). In the absence of PBD46, the calculated apparent 1st-order rate constants for the wt Cdc42 (WTkobs) (0.087 ± 0.004 min−1) and Cdc42(T35A) (T35Akobs) (0.084 ± 0.009 min−1) were approximately the same (Fig. 2). In addition, using an initial concentration of 2 mM GTP leads to a total amount of Pi released (Pi(max)) (and thus GDP produced) of 0.64 ± 0.01 mM for wt Cdc42 and 0.63 ± 0.01 mM for Cdc42(T35A) under our experimental conditions, suggesting that the mutation itself does not affect the intrinsic GTP hydrolysis efficiency of Cdc42 (Fig. 2). Presumably, at this concentration ratio of GTP to GDP there is no longer enough GTP to exchange with the bound GDP. In the presence of 30 μM PBD, no Pi was released for wt Cdc42, whereas for Cdc42 (T35A) Pi was released, but with a slower apparent 1st-order rate constant T35APBD46kobs of 0.046 ± 0.005 min−1. From Figure 2, it was also observed that the maximum amount of Pi released (and GDP formed) for Cdc42(T35A) in the presence of 30 μM PBD46 was 0.21 mM. There is almost 3-fold less GTP hydrolyzed than for Cdc42(T35A) in the absence of PBD46, even though the same 2 mM initial concentration of GTP was available. These results imply that a weaker and/or altered interaction between Cdc42(T35A) and PBD46 leads to a recovery of some GTP hydrolysis. A weaker binding affinity for a GAP protein was shown also for p21Ras(T35A) as compared to wt p21Ras by a factor of 12, and this subsequently altered the GAP efficiency for mutant p21Ras.13

Figure 2.

Kinetics of GTP Hydrolysis in the absence and presence of PBD46 for wt Cdc42 relative to Cdc42(T35A). Wt Cdc42 (Black line) and Cdc42(T35A) (Red line) in the absence of PBD46 shows the same rate of GTP hydrolysis, within error. In the presence of 30 μM PBD46, wt Cdc42 (Blue line) shows total inhibition of GTP hydrolysis relative to unbound wt Cdc42. Cdc42(T35A) (Purple line) shows both a slower intrinsic GTP hydrolysis rate in the presence of PBD46 relative compared to unbound in its absence Cdc42(T35A) and a lower level of maximum amount of phosphate that can be released after 30 minutes.

Molecular dynamics simulations

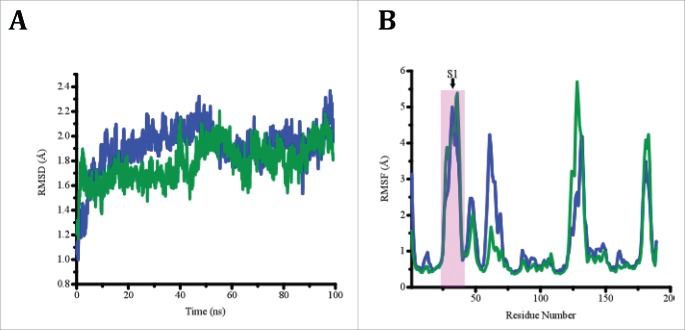

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed starting from the crystal structure of wt Cdc42 in the absence of an effector (PBD ID: 1AN0), and for Cdc42(T35A) after substituting Thr35 with Ala in PyMol (See Methods section). Figure 3A shows a plot of root mean square deviation (RMSD) values as a function of time step for both wt Cdc42 and Cdc42(T35A), and shows that the core residues remained well aligned throughout the time course of the simulation indicating that both proteins were relatively stable during the simulations. The root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) of Cα atoms (Fig. 3B) for both Cdc42 constructs provide a means to compare the average change in position over time of individual atoms, thus providing an estimate of the flexibility at each position of each Cdc42 construct. The data herein indicates that Switch 1 is relatively more flexible than the rest of the protein, as has been observed experimentally.19 Nonetheless, it appears that both Switch 1 and the structural region corresponding to Switch 2 in wt Cdc42 are dynamically coupled; however, this did not appear to be affected by the mutation. Comparing B-factors for residues in the Switch 2 region between the 2 chains of 1AN0.pdb (www.rcsb.org), there is a fair amount of discrepancy with one chain displaying much greater flexibility, and experimental data indicate Switch 2 is quite flexible in solution.8,19 Therefore, the crystal structure likely represents a metastable state and therefore is less likely to be maintained during the simulation. Molecular dynamics simulations were also performed on the NMR structure of wt Cdc42 complexed to a GTPase binding domain peptide of the effector ACK (PBD ID: 1CF4) to mimic PBD46. The structure of the wt Cdc42-PBD46 complex (PDB ID: 1EES) 14 did not have the coordinate assignments for GTP and Mg2+ and efforts to incorporate them into the complex did not facilitate a reasonable overall structure to submit for simulation. However, the coordinates for GTP and Mg2+ were available in the 3D structure of Cdc42 complexed to a GTPase binding domain of the effector ACK (PBD ID: 1CF4). Moreover, a sequence alignment of PBD46 and the corresponding residues of ACK show the similarity in the 2 peptides (Fig. 4). Therefore, since both structures, 1EES and 1CFR, were very similar, it was reasonable to use 1CF4 for all simulations involving the effector. Results of the simulations show that for Cdc42(T35A) in the presence of the effector, the orientation change seen for the GTP relative to the divalent cation that leads to the stabilization of the wt Cdc42-PBD46 interaction does not occur for the T35A variant in the presence of PBD46.

Figure 3.

(A) A plot RMSD as a function of time step for wt Cdc42 (blue) and Cdc42(T35A) (Green) in the absence of effector. (B) A plot of RMSF per residue for wt Cdc42 (Blue) and Cdc42(T35A) (Green) in the absence of effector. The Switch 1 (denoted by S1) region of residues in the proteins are highlighted by the pink box to show their similarity for both proteins.

Figure 4.

Sequence alignment of the PBD46 with ACK peptides. The sequence homology of the Cdc42 Ras Interactive Binding (CRIB) domain for both peptides are underlined in green italics.

Discussion

Our results highlight that a single-point mutation in the Switch 1 region of Cdc42, Cdc42(T35A) leads to the recovered ability of the GTPase to catalyze intrinsic GTP hydrolysis in the presence of PBD46. Our observations include: 1) The T35A mutation itself does not affect the overall GTP hydrolysis rate in the absence of PBD46; 2) The overall rate of GTP hydrolysis for Cdc42(T35A) slows down upon adding PBD46; 3) Once a saturating concentration of PBD46 is added with Cdc42(T35A), no further GTP hydrolysis occurred; and 4) Structural models suggest that the conformational changes induced by the effector in wt Cdc42, leading to the inhibition of GTP hydrolysis, are not possible for the Cdc42(T35A) variant. One possibility that was considered was that GDP may bind more tightly to Cdc42(T35A) in the presence of PBD46. However, as described in the introduction, previous 31P-NMR studies have shown that the nucleotide-binding site in Cdc42(T35A) is unaffected when PBD46 is bound.17 Moreover, p21Ras has been shown to bind to both GDP and GTP with similar affinity.13,20 Since the solution structure and backbone dynamics revealed that the Switch 1 region in Cdc42(T35A) experiences much less conformational freedom than the corresponding region in wt,19 rationalizing the above observations led us to believe that the changes in the backbone dynamics in Cdc42(T35A) may foster an interaction with PBD46 in a way that does not induce a conformational shift that inhibits Cdc42-stimulated GTP hydrolysis. We propose and discuss a potential structural model that is consistent with these observations.

Intrinsic GTP hydrolysis occurs for Cdc42(T35A) in the presence of PBD46

As stated earlier, Figure 1 shows that there is a linear decrease in Pi released both for wt Cdc42 and Cdc42(T35A) at lower concentrations of PBD46 added. The Kd characterizing the wt Cdc42-PBD46 interaction is reported to be in the nM range,6 which is supported by Figure 1, as wt Cdc42 shows complete inhibition of GTP hydrolysis at 10 μM PBD46. Moreover, the slopes of the graphs in Figure 1 are evidence that the apparent Kd for PBD46 binding to Cdc42(T35A) is higher than for wt Cdc42. However, for Cdc42(T35A), there is a saturation point in Figure 1 as above 17 μM PBD46, the activity does not approach zero. This implies that, not only could the binding of PBD46 to Cdc42(T35A) be weaker, but it also suggests that the slower dynamics of the Switch 1 region in Cdc42(T35A) facilitates an interaction between PBD46 but that allows GTP hydrolysis to occur.

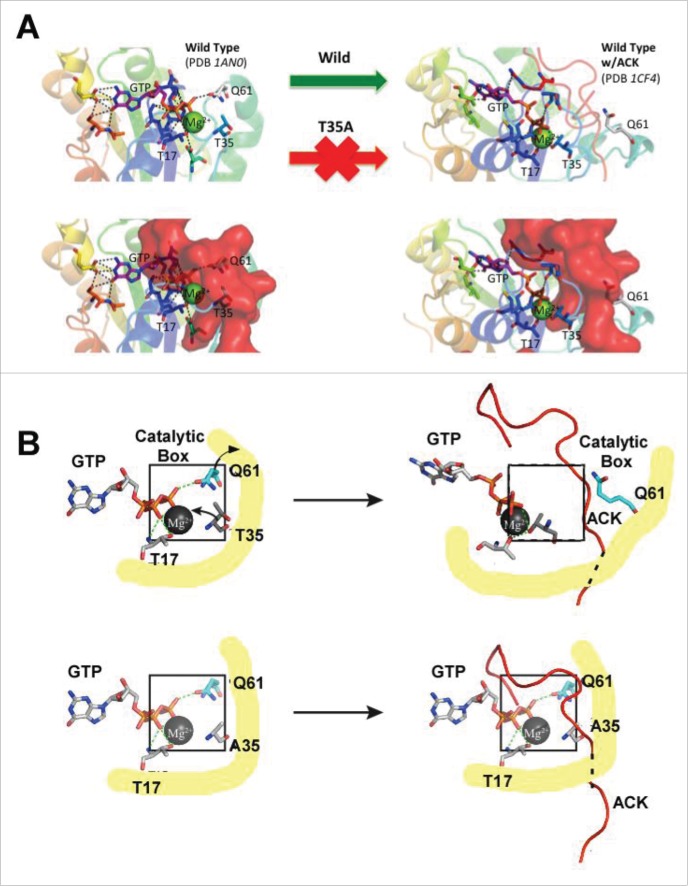

Kinetic studies in Figure 2 also support our proposed structural model of GTP hydrolysis for Cdc42(T35A) in the presence of PBD46. First, the finding that the apparent 1st-order rate constants are the same for wt and mutant Cdc42 in the absence of PBD46 implies that the Switch 1 mutation does not alter the mechanism of intrinsic GTP hydrolysis for Cdc42. Results of molecular dynamics simulation indicate little difference in the overall flexibility of the molecule and in particular switch 1 (Fig. 3). As T35 is located within Switch 1, this suggests that the substitution of T35 to alanine has little affect on hydrolysis. This is further supported by 31P-NMR data previously reported by Phillips et al. which showed only very small phosphorus chemical shift changes between Cdc42(T35A) and wt Cdc42 when bound to a nonhydrolyzable GTP analog, GMPPCP,17 indicating that the nucleotide is in a similar conformational state at the active site of the 2 proteins prior to effector interaction. Figure 2 however shows intrinsic GTP hydrolysis in the presence of PBD46 is still observed for Cdc42(T35A), albeit slower and saturating at a concentration of Pi released that is 3 times lower than in the absence of PBD46. The Kd values of GDP and GTP for Cdc42 are in the pM-nM range suggesting that nucleotide binding is very tight, 21 as is the case for other Ras-related proteins.13,20 This suggests that, as the concentrations of GDP and GTP present become similar in the presence of PBD46, GTP exchange for GDP on the Cdc42(T35A) variant will become significantly lower. Another explanation for the result in Figure 2 is that the Cdc42(T35A) variant shows a slightly higher GDP affinity than GTP in the presence of the PBD46 than in its absence, causing the lower GDP to GTP exchange. Previous studies showed that Ras(T35A) exhibits a 12-fold decrease in affinity for a GAP effector, as compared to wt Ras21. Based on structural studies on the effector-binding domain of wt Ras, the decrease in binding affinity of the effector for Ras(T35A) was attributed to differences in the interplay of structural interactions between Thr35 and the divalent Mg2+ in this Ras variant.13,22 We examined the structures of wt Cdc42 in the absence of an effector (PBD ID: 1AN0, unpublished results), as well as complexed to effectors (ACK, WASP, and PBD46).14,17,23-25 Figure 5 shows that of Cdc42 unbound, as well as bound to ACK (PDB ID: 1CF4), a 52 amino acid peptide derivative ACK tyrosine kinase, which binds to the Switch 1 region similarly to PBD46.25 Figure 5 (right) suggests that, in wt Cdc42, Thr35 does not interact with Mg2+ in the absence of effectors, but does so in the presence of effectors such as ACK (Fig. 5, left), PBD46 14 and WASP,24 a conformational change supported by the earlier observations for wt pRas21. This interaction likely causes a conformation that forces GTP away from the catalytic box, contributing to the inhibition of GTP hydrolytic activity when wt Cdc42 binds to PBD46. It is also interesting to note that line broadening observed in the 31P-NMR spectra of wt Cdc42 bound to PBD46 as compared to unbound Cdc42 17 suggested that there might be some conformational realignment of the nucleotide in the nucleotide-binding site upon PBD46 binding to wt Cdc42. The binding of PBD46 to wt Cdc42 could, in addition to the conformational changes that restrict GTP from approaching the catalytic site for hydrolysis, also foster an increased stabilization of GDP in the nucleotide-binding pocket of Cdc42. This might then impede the GDP-GTP exchange contributing to the inhibition of GTP hydrolysis.

Figure 5.

For figure legend see page .See previous page.(A) Upper Left: The PDB structure of 1AN0 depicting interactions between Cdc42, GTP and Mg2+. Note that catalytic Q61 interacts with the γ-phosphate of GTP. While T17 forms a complex with Mg2+ in wt Cdc42 but not in Cdc42(T35A). Lower Left: 1AN0) aligned to PDB 1CF4 leaving only ACK in its bound orientation. As shown in the image, ACK rests in the position occupied by GTP and Mg2+ in this GTP hydrolysis competent state. Right: The PDB structure of 1CF4 with ACK bound depicting the new interaction for the shifted GTP/Mg2+ position. Here, Q61 is blocked from interaction with GTP with T35 forming a complex with Mg2+ not present in the unbound structure (The red arrow indicates the T35A mutation would not allow this transition); (B) Upper Left: GTP/Mg2+ interactions in the catalytic box of wt Cdc42. Upper Right: Upon binding, PBD46/ACK, T35 interacts with Mg2+ pulling GTP out of the catalytic box. Lower Left: The T35A mutation has little effect on the GTP/Mg2+ complex in the absence of the effector. Lower Right: The T35A substitution does, however, prevent the stabilization of the shifted position. The Mg2+ ion is shaded gray, the phosphates of the nucleotide are shaded orange with the oxygen atoms red. The ACK effector is shaded red with the dashed line representing its backbone that is under the yellow shaded region. The catalytic boxes are outlined in black in both upper and lower panels of figure B. The yellow shaded regions depict the protein backbone.

Structural analysis shown in Figure 5 suggests that the missing hydroxyl group in Cdc42(T35A) in the presence of PBD46 results in the Mg2+ no longer being tightly held in the shifted position as shown for the wt Cdc42-PBD46 complex, thereby eliminating the transition to a conformation that leads to the inhibition of GTP hydrolysis (indicated by red arrow in Fig. 5A). The absence of the T35 hydroxyl would therefore allow GTP and Mg2+ ion to remain largely in their original state, likely displacing the C-terminal bound region of the effector (Fig. 5B, lower left). This would allow the GTP to remain susceptible to hydrolysis, albeit inhibited by competition with the effector tail for the GTP/Mg2+ site (Fig. 5B, lower right). Moreover, the plateau shown in Figure 2 for GTP hydrolysis for Cdc42(T35A) in the presence of PBD46 also suggests that GDP might by more tightly stabilized [i.e. have a higher affinity for Cdc42(T35A)] in the presence of PBD46, as discussed above for wt-PBD46 complex,17 which could limit the maximum amount of GTP that could be hydrolyzed by this Cdc42 variant in the presence of PBD46. Another possible explanation for the reduced GTPase activity of the Cdc42(T35A) variant in the presence of PBD46 is that there are 2 populations (conformers), one of which is active and another that is inactive in the presence of the GTPase inhibitor. However, for this interpretation to be valid, it would be necessary for there to be a time-dependent change from the active conformation to the inactive conformation on the timescale of the hydrolysis experiment. If these 2 populations were static, it would lead to GTP being hydrolyzed to the same level as the wild type, albeit at a slower rate due to the lower active concentration of Cdc42. For the saturation level for GTP hydrolysis in the T35A mutant to be lower than the wild type, the active conformation would have to assume an inactive conformation before all the available GTP is used up. While this explanation is plausible, we have not yet found direct evidence for multiple interconverting conformations on this slow timescale, so we currently favor the higher GDP affinity explanation for the difference in saturation level. However, more work is needed to unambiguously provide an exact interpretation for the reduced saturation level of GTP hydrolysis.

The 1CF4 structure was used in molecular dynamics simulations to examine the stability of the shifted position with the mutation as compared to wt in the presence of the effector ACK. If T35 were necessary to produce and maintain the shifted orientation then, while the wild-type structure would remain stable, the mutant would change conformation. As expected, in the wild-type Cdc42-effector complex, Mg2+ and GTP remained tightly bound in their original position. However, in the Cdc42(T35A)-effector complex, the GTP and Mg2+ drifted from their initial location rapidly during the simulation with the switch 1 region disengaging the Mg2+ ion forcing ACK into a new position. This suggests that Cdc42(T35A), in the presence of an effector such as ACK or PBD46, is likely unable to transition to the state observed for the wt Cdc42-effector complex structure due to the mutation. Therefore, Thr35 is a critical component in facilitating the transition and stabilization of the inhibitory state for Cdc42.

We also analyzed the solution structure of PBD46 bound to wt Cdc42 (pdb ID: 1EES) and observed, among several others involving Switch 1 residues, interactions between T35 on Cdc42 and residues A24 and V25 on PBD46, highlighting the importance of T35 in targeting the effector protein.14 Our present studies strongly suggest that some of the interactions that stabilize the binding interface between PBD46 and wt Cdc42 could be altered for Cdc42(T35A). As such, our data point toward efforts to further modify the GTP hydrolysis rates and efficiencies in the presence of effectors such as PBD46 by fine-tuning these apparent conformational changes using site-directed mutagenesis. To this end, a full structural characterization of the binding interface between Cdc42(T35A) and PBD46 will be of subsequent significant interest in order to: 1) observe which stabilizing interactions are lost or altered in the Cdc42(T35A)-PBD46 complex, and 2) address the molecular details surrounding the altered dynamics in Cdc42(T35A) and how this perturbs or “prevents” a stronger interaction with PBD46. Such knowledge can be expected to provide a more complete understanding of the interplay of molecular forces that help regulate normal and abnormal cell events.

Since it has been shown that the binding interface between Cdc42 and PBD46 involves the Switch 1 region, it must be considered a possibility that a targeted small molecule could potentially disturb the wt Cdc42-PBD46 interaction, as well as further inhibit the Cdc42(T35A)-PBD46 interaction if it could be targeted to the Switch 1 region. Recently, virtual screening studies identified a small molecule ZCL278, which targeted the Switch 1 binding region on Cdc42 and “mimicked” an interaction between Cdc42 and a Guanine Exchange Effector (GEF) Intersectin.26 Biochemical assays revealed that the Cdc42-ZCL278 interaction inhibited several Cdc42-stimulated cellular processes as well.26 One possible explanation for these findings could be that ZCL278 has a direct effect on the Intersectin binding interface with Cdc42. Also, it must be considered that ZCL278 could alter the conformation and/or dynamics in Switch 1, thereby affecting indirectly the activity stimulated by Intersectin upon binding. Related findings describe the influence of the small molecule Zn2+-cyclen's on the conformational state of Ras that weakly binds to effectors.27 Moreover, these studies revealed that for the Ras(T35A) variant, the cyclen not only stabilized the weak-effector binding state, but also increased the inhibitory effect of the interaction.27 It is important to consider that, in addition to directly blocking protein interactions, a small molecule could also be used to alter the flexibility in a region of Cdc42 that could alter the interaction with an effector. Such an effect could furthermore be enhanced for a Ras variant that exhibits different backbone dynamics. To date, protein-protein interactions (PPIs) have remained an elusive front for small molecule design, mostly because of the difficulty in experimentally determining feasible binding interfaces on the protein(s) to test.28 Our studies have highlighted the correlation between conformational dynamics underlying Ras-related protein interactions and the understanding of functional interactions of target/effector molecules with Ras-related proteins.

Conclusion

The inactivation of Ras oncogenic signaling has been correlated to tumor reduction, highlighting the importance of the Ras proteins as targets for treatment of the oncogenic state.7 The data presented highlight that the mechanism of intrinsic GTP hydrolysis is not disturbed by a T35A mutation in Cdc42. However, a peptide derivative of a GTPase inhibitor, PBD46, binds differently to this mutant as compared to wt Cdc42 and the conformation of the variant Cdc42-PBD46 complex is one in which the catalytic site for hydrolysis is still accessible to GTP. Our observations also highlight that changes in backbone dynamics at important interacting regions may be critical for the control of Ras-protein interactions and the regulation of cell signaling. Since relevant effector binding regions can be flexible and may exhibit multiple conformations, one subsequent approach to drug design could involve the development of small-molecule targets that may bind at an adjacent site on Ras and restrict conformational flexibility, so as to weaken or block an effector protein interaction and inactivate oncogenic Ras behavior.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

The proteins Cdc42 (WT and T35A) and PBD46 were cloned, expressed and purified as His6-tagged (Cdc42 constructs) or GST-tagged (PBD46) fusion proteins and purified as described previously.19,29 UV absorbance at 280 nm was used to ascertain the protein concentration and SDS-PAGE was used to verify the protein purity.

GTP hydrolysis assay

Cdc42 constructs were nucleotide exchanged as previously described.19 Samples were prepared by mixing together a given GTP-bound Cdc42 construct (10 μM) with PBD46 (30 μM). For kinetics experiments, each protein sample was mixed with 2 mM GTP in 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 8.0 (J.T. Baker), in a volume of 1 mL and incubated at 25°C. After time intervals of 0–90 minutes, the hydrolysis reaction was stopped via protein denaturation by taking a 150μL aliquot of the protein sample and adding it to 150 μL of 12% SDS. For the GTP hydrolysis assay as a function of PBD46 concentration, 10 μM of a Cdc42 protein was incubated with varying concentrations of PBD46 for 30 min and aliquots were extracted and denatured as described above. To monitor GTP hydrolysis, each protein-SDS solution was incubated with a 750 μL solution containing 25% ascorbic acid and 0.5% ammonium molybdate at room temperature. A 50 μL solution consisting of sodium citrate, sodium meta-arsenite and acetic acid (1% each by volume) was added to the denatured protein mixture. Following incubation for an additional 20 minutes, a 1.05 mL was assayed for color change at 850 nm. 30 GTP was used as a control to show that no hydrolysis occurred in the absence of protein. To calibrate the assay and ensure that hydrolysis was measured for only the GTP bound to the desired protein construct, GTP was added after denaturing the protein construct and the absorbance of this sample was read and subtracted from the desired sample absorbance at each time point. Using K2HPO4 as the phosphate source, concentrations ranging from 0–75 nM were assayed in triplicate to generate a linear standard curve. Values from quadruplicate experiments were averaged to calculate the average amount of Pi released as a function of time for each set of protein(s), with standard deviations from each experiment. The kinetics for the release of Pi were plotted for the wild-type and Cdc42(T35A) in the absence and presence of PBD46 according to equation 1:

| (1) |

where Pi(t) is the amount of inorganic phosphate released per time (t), Pi(max) is the maximum amount of inorganic phosphate released at t = ∞, kobs is the observed, apparent (pseudo-) first-order rate constant.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed using the crystal structure for wt Cdc42 in the absence of an effector (PDB ID: 1AN0) (Unpublished data) and the NMR structure of Cdc42 bound to the GTPase binding domain of the effector ACK (PDB ID: 1CF4).25 The parameters for GTP were prepared from the parameters for the guanine nucleotide and the triphosphate attached ribose of ATP. A terminal phosphate was added to GDP to form GTP in 1AN0, and GMPPNP bound in 1CF4 was altered to GTP for the simulations. Both structures included Mg2+ in its bound position. The threonine to alanine mutation(s) were made using PYMOL.31 Each construct was prepared and equilibrated separately. After minimization the proteins were solvated and neutralized leaving an effective concentration of 150mM NaCl. Equilibration was carried out in the NPT ensemble using NAMD 2.9 and the CHARMM27 force field.32-34 A temperature of 300K was maintained using Langevin dynamics with a constant pressure of 1atm maintained using the Langevin piston method. Long-range electrostatic interactions were computed using the particle mesh Ewald method with periodic boundary conditions. Electrostatic and Van der Waals interactions were cut-off beyond a distance of 12Å using switching functions beginning at 10Å. All hydrogen atoms were kept rigid and a time step of 1fs was used. In the first equilibration step the protein atoms were fixed and the system was subjected to 1,500 steps of minimization and 50ps of dynamics followed by the use of harmonic constraints on the protein atoms with a force constant of 1 kcal/(mol Å2) for 50ps. In the final step before production runs, constraints were removed and a gradual temperature increase from 0K to 300K was implemented followed by 250ps of unrestrained dynamics. Production runs consisted of 100ns of dynamics using a 2fs time step with all other parameters identical to the last 250ps of equilibration. VMD and tools therein were used to prepare the structures for simulation and for analysis.35

Abbreviations

- Cdc42

Cell division cycle 42

- GAP

GTPase Activating Protein

- PAK

P(21)-activated kinase

- PBD46

PAK Binding Domain 46

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- RBD

Ras binding domain

- GDI

guanine dissociation inhibitor

- IPTG

Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs. Roger Koeppe II, and Robert Oswald for critical review of this manuscript, and Reena Chandrashekar for technical assistance with the GTP hydrolysis assays.

Funding

This publication was supported by Grant Number 1K-O1-CA113753 to P.D.A. and 1RO1-CA-1726311 from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Grant Number P30 GM103450 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH, Department of Energy (DOE grant #DE-FG0–01ER15161) the Arkansas Biosciences Institute, and the Arkansas Science and Technology Authority.

References

- [1].Bos JL, Toksoz D, Marshall CJ, Verlaan-de Vries M, Veeneman GH, van der Eb AJ, van Boom JH, Janssen JW, Steenvoorden AC. Amino-acid substitutions at codon 13 of the N-ras oncogene in human acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature (1985); 315:726-30; PMID:2989702; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/315726a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Barbacid M. ras Genes. Ann Rev Biochem (1987); 56:779-827; PMID:3304147; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.004023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bourne HR, Sanders DA, McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: Conserved Structure and Molecular Mechanism. Nature (1991); 349(6305):117-27; PMID:1898771; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/349117a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].White MA, Nicolette C, Minden A, Polverino A, Van Aelst L, Karin M, Wigler MH. Multiple Ras functions can contribute to mammalian cell transformation. Cell (1995); 80:533-41; PMID:7867061; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90507-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Adjei AA. Ras signaling pathway proteins as therapeutic targets. Curr Pharm Des (2001); 7:1581-94; PMID:11562300; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/1381612013397258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Guo W, Sutcliffe MJ, Cerione RA, Oswald RE. Identification of the binding surface on Cdc42Hs for p21-activated kinase. Biochemistry (1998); 37:14030-7; PMID:9760238; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi981352+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chandrashekar R, Adams P “Prospective Development of Small Molecule Targets to Oncogenic Ras Proteins. Open J Biophys (2013); Vol. 3:pp. 207-11; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4236/ojbiphy.2013.34025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Feltham JL, Dotsch V, Raza S, Manor D, Cerione RA, Sutcliffe MJ, Wagner G, Oswald RE. Definition of the switch surface in the solution structure of Cdc42Hs. Biochemistry (1997); 36:8755-66; PMID:9220962; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi970694x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Loh AP, Guo W, Nicholson LK, Oswald RE. Backbone dynamics of inactive, active, and effector-bound Cdc42Hs from measurements of (15)N relaxation parameters at multiple field strengths. Biochemistry (1999); 38:12547-57; PMID:10504223; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi9913707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gonzalez-Romo P, Sanchez-Nieto S, Gavilanes-Ruiz M. A modified colorimetric method for the determination of orthophosphate in the presence of high ATP concentrations. Analytical biochemistry (1992); 200:235-8; PMID:1632487; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90458-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Spoerner M, Herrmann C, Vetter IR, Kalbitzer HR, Wittinghofer A. Dynamic properties of the Ras switch I region and its importance for binding to effectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2001); 98:4944-9; PMID:11320243; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.081441398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dalcin PT, Piovesan DM, Kang S, Fernandes AK, Franciscatto E, Millan T, Hoffmann C, Innocente C, Pereira RP, Menna Barreto SS. Factors associated with emergency department visits due to acute asthma. Braz J Med Biol Res (2004); 37:1331-8; PMID:15334198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].John J, Rensland H, Schlichting I, Vetter I, Borasio GD, Goody RS, Wittinghofer A. Kinetic and structural analysis of the Mg(2+)-binding site of the guanine nucleotide-binding protein p21H-ras. J Biol Chem (1993); 268:923-9; PMID:8419371 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gizachew D, Guo W, Chohan KK, Sutcliffe MJ, Oswald RE. Structure of the complex of Cdc42Hs with a peptide derived from P-21 activated kinase. Biochemistry (2000); 39:3963-71; PMID:10747784; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi992646d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gizachew D, Oswald RE. Concerted Motion of a Protein-Peptide Complex: Backbone Dynamics Studies of an 15N-Labeled Peptide Derived from P21-Activated Kinase Bound to Cdc42Hs•GMPPCP. Biochemistry (2001); 40:14368-75; PMID:11724548; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi010989h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tu SS, Wu WJ, Yang W, Nolbant P, Hahn K, Cerione RA. Antiapoptotic Cdc42 mutants are potent activators of cellular transformation. Biochemistry (2002); 41:12350-8; PMID:12369824; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi026167h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Phillips MJ, Calero G, Chan B, Ramachandran S, Cerione RA. Effector proteins exert an important influence on the signaling-active state of the small GTPase Cdc42. J Biol Chem (2008); 283:14153-64; PMID:18348980; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M706271200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Farnsworth CL, Feig LA. Dominant inhibitory mutations in the Mg(2+)-binding site of RasH prevent its activation by GTP. Mol Cell Biol (1991); 11:4822-9; PMID:1922022; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.11.10.4822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chandrashekar R, Salem O, Krizova H, McFeeters R, Adams PD. A switch I mutant of Cdc42 exhibits less conformational freedom. Biochemistry (2011); 50:6196-207; PMID:21667996; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi2004284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].John J, Sohmen R, Feuerstein J, Linke R, Wittinghofer A, Goody RS. Kinetics of interaction of nucleotides with nucleotide-free H-ras p21. Biochemistry (1990); 29:6058-65; PMID:2200519; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi00477a025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhang B, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Zheng Y. The role of Mg2+ cofactor in the guanine nucleotide exchange and GTP hydrolysis reactions of Rho family GTP-binding proteins. J Biol Chem (2000); 275:25299-307; PMID:10843989; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M001027200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wittinghofer A, Pai E. The Structure of Ras protein: a Model for a Universal Molecular Switch. Trends Biomed Sci (1991); 16:382-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90156-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Abdul-Manan N, Aghazadeh B, Liu GA, Majumdar A, Ouerfelli O, Siminovitch KA, Rosen MK. Structure of Cdc42 in complex with the GTPase-binding domain of the ‘Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome’ protein. Nature (1999); 399:379-83; PMID:10360578; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/20726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Morreale A, Venkatesan M, Mott HR, Owen D, Nietlispach D, Lowe PN, Laue ED. Structure of Cdc42 bound to the GTPase binding domain of PAK. Nat Struct Biol (2000); 7:384-8; PMID:10802735; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/75158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mott HR, Owen D, Nietlispach D, Lowe PN, Manser E, Lim L, Laue ED. Structure of the small G protein Cdc42 bound to the GTPase-binding domain of ACK. Nature (1999); 399:384-8; PMID:10360579; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/20732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Friesland A, Zhao Y, Chen YH, Wang L, Zhou H, Lu Q. Small molecule targeting Cdc42-intersectin interaction disrupts Golgi organization and suppresses cell motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2013); 110:1261-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rosnizeck IC, Filchtinski D, Lopes RP, Kieninger B, Herrmann C, Kalbitzer HR, Spoerner M. Elucidating the mode of action of a typical Ras state 1(T) inhibitor. Biochemistry (2014); 53:3867-78; PMID:24866928; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi401689w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mullard A. Protein-protein interaction inhibitors get into the groove. Nat Rev Drug Discov (2012); 11:173-5; PMID:22378255; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrd3680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Adams PD, Oswald RE. NMR assignment of Cdc42(T35A), an active Switch I mutant of Cdc42. Biomol NMR Assign (2007); 1:225-7; PMID:19636871; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12104-007-9062-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fernandes DJ, McConville JF, Stewart AG, Kalinichenko V, Solway J. Can we differentiate between airway and vascular smooth muscle?. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol (2004); 31:805-10; PMID:15566398; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.04084.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Seeliger D, de Groot BL. Ligand docking and binding site analysis with PyMOL and Autodock/Vina. J Comput-Aided Mol Des (2010); 24:417-22; PMID:20401516; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10822-010-9352-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Brooks BR, Brooks CL 3rd, Mackerell AD Jr., Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, et al.. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J Comput Chem (2009); 30:1545-614; PMID:19444816; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcc.21287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mackerell AD Jr., Feig M, Brooks CL 3rd. Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem (2004); 25:1400-15; PMID:15185334; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcc.20065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem (2005); 26:1781-802; PMID:16222654; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcc.20289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J Mol Graph (1996); 14:33-38, 27–38; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]