Abstract

Multiple Kv channel complexes contribute to total Kv current in numerous cell types and usually subserve different physiological functions. Identifying the complete compliment of functional Kv channel subunits in cells is a prerequisite to understanding regulatory function. It was the goal of this work to determine the complete Kv subunit compliment that contribute to functional Kv currents in rat small mesenteric artery (SMA) myocytes as a prelude to studying channel regulation. Using RNA prepared from freshly dispersed myocytes, high levels of Kv1.2, 1.5 and 2.1 and lower levels of Kv7.4 α-subunit expression were demonstrated by quantitative PCR and confirmed by Western blotting. Selective inhibitors correolide (Kv1; COR), stromatoxin (Kv2.1; ScTx) and linopiridine (Kv7.4; LINO) decreased Kv current at +40mV in SMA by 46 ± 4%, 48 ± 4% and 6.5 ± 2%, respectively, and Kv current in SMA was insensitive to α-dendrotoxin. Contractions of SMA segments pretreated with 100 nmol/L phenylephrine were enhanced 27 ± 3%, 30 ± 8% and 7 ± 3% of the response to 120 mmol/L KCl by COR, ScTX and LINO, respectively. The presence of Kv6.1, 9.3, β1.1, and β1.2 was demonstrated by RT-PCR using myocyte RNA with expression of Kvβ1.2 and Kv9.3 about 10-fold higher than Kvβ1.1 and Kv6.1, respectively. Selective inhibitors of Kv1.3, 3.4, 4.1 and 4.3 channels also found at the RNA and/or protein level had no significant effect on Kv current or contraction. These results suggest that Kv current in rat SMA myocytes are dominated equally by two major components consisting of Kv1.2-1.5-β1.2 and Kv2.1-9.3 channels along with a smaller contribution from Kv7.4 channels but differences in voltage dependence of activation allows all three to provide significant contributions to SMA function at physiological voltages.

Keywords: Kv subunits, gene expressions, protein expression, smooth muscle cells, toxin inhibitors, Kv currents, contractile effects

INTRODUCTION

Voltage gated K+ channels (Kv) play an important role in the regulation of contraction in arterial smooth muscle (ASM) (1). This is due to the central role they play in determining membrane potential (2) and consequently the open probability of voltage gated Ca2+ channels (3). The latter represent an important source of activator Ca2+ for tonic contraction in ASM especially in resistance arteries (3). Kv channels (KCN) are also the targets of extracellular and intracellular signaling that contribute to the regulation of arterial function in vivo as well as to the remodeling associated with vascular disease and aging (4).

KCN comprise a large gene family consisting of pore-forming α-subunits that are often associated with transmembrane or intracellular accessory subunits (5,6). Most KCN subfamilies have multiple members some of which are subject to alternative splicing, heteromultimeric assembly, and post-translational modification (7,8). As a result, there is a large, potential pool of KCN subunit combinations with different functional characteristics (4,7,8).

Past studies have demonstrated the presence of multiple Kv subunits in ASM cells (ASMC) from several vascular sites based upon mRNA and/or protein expression (9-16), biophysical properties and/or pharmacology of Kv currents in isolated cells (14-20), and/or responses of artery segments to K+ channel reagents (15-20). In general, studies at the mRNA level have suggested expression of a larger number of Kv subunits than studies at the protein or functional level (9,11,13). However, this could be due in part to limitations in available reagents such as antibodies or selective inhibitors producing false positive as well as false negative results.

Such an analysis is important because various Kv subunits have different functional properties (4,7,8,21) and are differentially regulated (22,23). Furthermore, the presence of accessory subunits can confer unique regulatory function to α-subunits (24,25). It was previously shown that KCN in ASMC are inhibited by increases in intracellular Ca2+ (26,27) which likely contributes to the membrane depolarization associated with agonist activation (2). However, nothing is known of the specific Kv components that contribute to this effect. Thus, determining the complete composition of functionally significant Kv subunit combinations is a necessary prerequisite to understanding their contribution to this as well as other regulatory processes in ASM (28). Accordingly, the goal of this study was to determine using multiple methods the Kv components that contribute to the functional activity of ASMCs in rat small mesenteric artery (SMA) as a model arterial site. It is important to note that the functional Kv composition is likely to vary among different anatomical sites in both a size and organ specific manner contributing to site-specific regulatory function (1,4).

METHODS

Animals and Tissues

Arteries from 16-18 week old male Wistar Kyoto rats were used for RNA and protein isolation, for single cell patch clamp studies, and for mechanical studies. Animals were handled in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Lankenau Institute for Medical Research.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR

Following removal from animals, segments of SMA and tail artery (TA) were cannulated with a blunted 22 gauge needle and air was passed through the vessel lumen by gentle pressure (29). This process has been reported to remove endothelial cells and was confirmed herein using intact segments by the lack of a response to 1 μmol/L acetylcholine following contractions induced by 120 mmol/L KCl under isometric conditions. Total RNA was isolated from tissues by homogenization in Tri-reagent (RiboPure, Ambion, Austin, TX). RNA was also prepared from ASMCs enzymatically dispersed from SMA and TA by papain and collagenase treatment (27). Total RNA was also prepared from brain by homogenization in guanidinium isothiocynate followed by centrifugation through a CsCl step gradient as described (30). RNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop 2000c, Thermo Sci., Wilmington, DE). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and random hexamer primers (30). First strand reactions were also performed in which the reverse transcriptase enzyme was omitted (RT-reactions) as a negative control for first strand synthesis. Conventional PCR with gene-specific primers was performed using Titanium Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) (30). Additional PCR templates included 500 ng of rat brain cDNA (positive RT control), and 500 ng of rat genomic DNA and water as positive and negative PCR controls, respectively.

Real Time qPCR

Real time (quanitative) PCR was performed with AmpliTaq Gold polymerase and gene specific expression assays (Eurofins MWG Operon, Huntsville, AL) using a Mastercycler ep realplex (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY) as described (31). The abundance of Kvβ1.1 versus β1.2, Kv6.1 versus Kv9.3 and Kv7.4 versus Kv2.1 were compared using the 2−ΔΔCt method directly comparing expression in the same samples (32).

Protein Anaylsis

Segments of SMA along with TA, thoracic aorta, left ventricular free wall and/or brain were rapidly isolated, and placed in cold isolation buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Complete mini, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland; Halt, Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The tissues were cleaned, cut into small pieces, and homogenized in RIPA buffer as described (31). Protein concentration was determined using the BioRad DC Protein Assay with albumin as the standard.

Immunoblotting

Aliquots of proteins (5-30 μg) were size fractionated by SDS-PAGE using 7% Tris-acetate gels (31). Proteins were electroblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes which were incubated in blocking buffer (5% dry milk plus 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature then with primary antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Membranes were rinsed, incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, and treated with chemiluminescent reagent (Clarity, BioRad). Finally, abundance was quantitated by image analysis (FluorS MultiImager and Image One Software, BioRad Corp., Hercules, CA) as described (31).

Immunoprecipitation

Protein lysates (200 μg) were incubated overnight with antibodies (2-6 μg) at 4°C to form immunocomplexes. The latter were captured with pre-cleared protein G-agarose beads by gentile mixing for 4 hours at 4°C followed by centrifugation. The supernatant was removed and the beads washed 3X with cold RIPA buffer (31). SDS loading buffer was added to the beads and heated at 70°C for 10 min. Aliquots of precleared lysate, supernatant and immunocomplexes were separated by SDS-PAGE using 7% Tris-acetate gels (31).

Immunofluorescence

Dispersed cells were plated on glass coverslips, fixed with cold 4% paraformaldehyde, washed, and incubated with blocking buffer for 30 min on ice. They were then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, washed with cold PBS (3X for 5 min) and incubated with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody in blocking buffer at room temperature for 60 min in the absence of light. The coverslips were again washed with cold PBS (3X for 5 min), briefly air dried and covered with VectaShield mounting media with DAPI (Vector Labs., Burlingame, CA). The slides were covered with glass and viewed using an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axioplan, Thornwood, NY) with a Plan Neofluar 40X/1.3 oil immersion objective. Images were captured with an Axiocam CCD camera using AxioVision software (Zeiss).

Electrophysiology

ASMCs freshly isolated from SMA were used for the determination of Kv currents by whole cell, voltage clamp methods at room temperature (~21°C) as previously described in detail (27).

Contractile Studies

Second or third order mesenteric artery branches were cut into 2-3 mm long segments and mounted in vitro at their optimum length for isometric force development in a temperature-controlled bath at 37°C as previously described (33). Following an initial 2-3 hour equilibration period, responses to 120 mmol/L KCl were recorded in duplicate. Following recovery, responses to Kv inhibitors were obtained as described in the Results section. Force data were digitized (MacLab 8e; AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) at a sampling interval of 50 msec and stored on a computer (Macintosh G4, Apple Computers, Cupertino, CA) for off-line analysis. Tangential wall stress was calculated from force measurements using segment wet weight and dimensions as described (33).

Chemicals

Anti-Kv1.2, Kv7.4, Kvβ1.1 and Kvβ1.2 were obtained from Antibodies, Inc. (Davis, CA); anti-Kv1.5 and anti-actin from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO); anti-Kv2.1 from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY); anti-Kv3.4 and anti-Kv4.1 from Alomone Labs (Jerusalen, Isreal); anti-Kv4.3 from Millipore (Temecula,CA); anti-Kv6.1 from Abcam Inc., (Cambridge, MA); and anti-Kv9.3 from Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA).

Solutions

For electrophysiological studies, the perfusion solution contained (in mmol/L) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES and 10 glucose at pH 7.4 (with NaOH) while the pipet solution contained ( in mmol/L) 140 KCl, 1 MgCl, 5 NaCl, 5 Na2ATP, 10 HEPES and 10 BAPTA (pH 7.3 with KOH).

For contraction studies, the external solution aerated with (95% O2 and 5% CO2) contained (in mmol/L) 114 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 24 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 2.4 Na2HPO4 and 11 glucose at pH of 7.4.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot v12.0 (Systat Software Inc.; San Jose, CA). Comparisons of current-voltage data between groups were made with One or Two Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). When the ANOVA produced a significant P value, comparisons were made using the Bonferroni test for paired data, or using Dunnett's Test for multiple comparisons. Probability values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Data are given as mean ± 1 SEM.

RESULTS

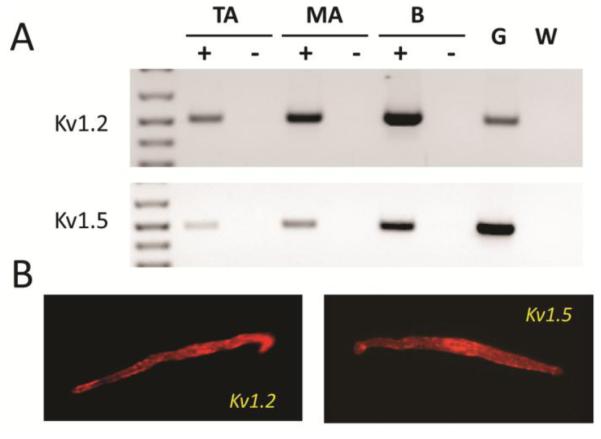

Gene expression of Shaker Kv1 α-subunits was surveyed by conventional PCR (cPCR) using RNA isolated from ASMC of SMA and TA. Expression of Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 α-subunits were found at high levels at both arterial sites (Fig 1A). Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 immunofluorescence was also detected in isolated myocytes from SMA (Fig 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 are expressed at the RNA and protein level in isolated smooth muscle cells from SMA. A: Ethidium bromide stained agarose gel of cPCR products for Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 in RNA from freshly dispersed tail (TA) and small mesenteric arteries (SMA) cells. First strand products from reactions performed in the presence (+) or absence (−) of reverse transcriptase were used as templates for PCR. Brain RNA (B) was used as a positive control for cDNA synthesis while genomic DNA (G) and water (W) were used as PCR templates for positive and negative PCR controls. B: Immunofluorescence detection of Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 protein in freshly dispersed SMA myocytes.

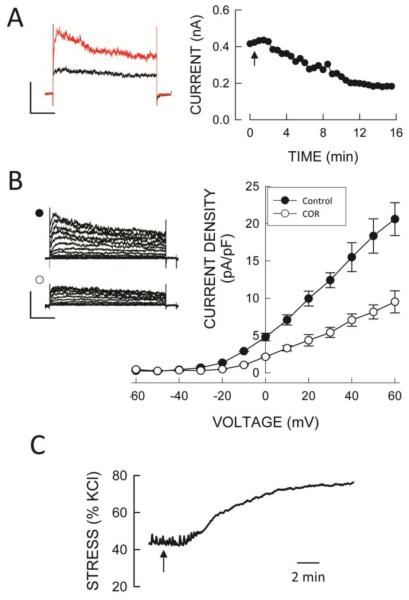

The contribution of Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 channels to whole cell Kv currents was assessed from the response to the selective Kv1 channel inhibitor correolide (34). Following inhibition of BKCa channels by 100 nmol/L iberiotoxin (IbTx) and L-type Ca+-channels with 1 μmol/L nifedipine, the addition of 10 μmol/L correolide produced a slowly developing inhibition of K+ current that averaged 46 ± 4% (n=8) of total at a test voltage of +40mV (Fig. 2A) and was voltage independent (Fig. 2B). The correolide-insensitive current appeared to be kinetically distinct in that it activated and inactivated more slowly than the correolide-sensitive K+ current (Fig. 2B left). To demonstrate that correolide-sensitive Kv channels are functionally important we tested the effect of correolide on contractile responses of SMA segments. Segments precontracted with 100 nmol/L phenylephrine (28 ± 3% of the response to 120 mmol/L KCl) exhibited robust but slowly developing responses to 10 μmol/L correolide that averaged 27 ± 3% of the response to 120 mmol/L KCl (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Functionally expression of Kv1 channels in SMA. A. Time course of inhibition of whole cell Kv current by correolide (10 μmol/L) at +40mV from a holding potential of −80 mV (1 sec duration voltage steps at 30 sec intervals) in the presence of 100 nmol/L IbTx and 1μmol/L nifedipine. Traces on the left show currents before and 15 min after correolide addition. B. Summary of whole cell Kv current-voltage relations before and after the addition of correolide in the presence of IbTx and nifedipine recorded from a holding potential of −80 mV (with 10 mV, 1 sec steps at 20 sec intervals). Representative families of currents are shown on the left before (•) and with correolide (○). Symbols are mean values and vertical bars are ± 1 SEM (n=8). Horizontal and vertical calibration bars in A and B represent 200 pA and 200 msec, respectively. C. Effect of 10 μmol/L correolide (arrow) on wall stress (% of KCl) of an SMA segment precontracted with 100 nmol/L phenylephrine. Horizontal bar represents 2 min.

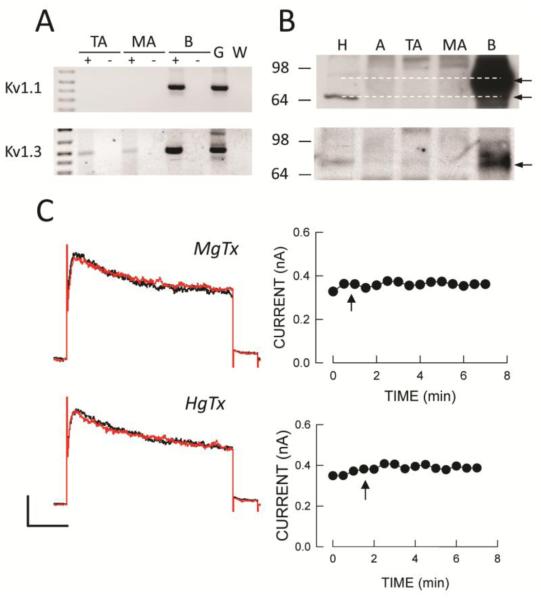

We previously reported gene expression of other members of the Shaker Kv1 family in intact SMA segments that are also known to be correolide-sensitive, specifically Kv1.1 and 1.3 (30). We found expression of Kv1.3 but not Kv1.1 in RNA from both SMA and TA myocytes (Fig 3A). Also a low abundance Kv1.3 protein band appeared to be present in lysates from all tissues but at much lower levels compared to brain while Kv1.1 protein was not present in arteries (Fig 3B). However, neither hongotoxin (a Kv1.1 and Kv1.3 inhibitor) nor margatoxin (a Kv1.3 inhibitor) had any significant effect on whole cell K+ currents in SMA myocytes (Fig 3C) or on contraction of SMA segments (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Correolide-sensitive Kv1.1 and Kv1.3 channels are not present in SMA myocytes. A: Expression of Kv1.1 and Kv1.3 in TA and SMA cellular RNA, and brain (B) by cPCR. B: Kv1.1 and Kv1.3 protein expression by Western blot analysis of tissue lysates from heart (H), aorta (A), TA, SMA and B. C: Neither margotoxin (MgTx; 10 nmol/L) nor hongotoxin (HgTx; 10 μmol/L) had a significant effect on whole cell Kv currents recorded in the presence of IbTx and nifedipine. Voltage clamp protocols are as described in Figure 2. Horizontal and vertical calibration bars represent 100 pA and 200 msec, respectively.

To determine if Kv1.2 subunits are present in homotetrameric or heterotetrameric assemblies, we evaluated the effects of α-dendrotoxin on SMA Kv currents (35). Exposure to 100 nmol/L α-dendrotoxin had no significant effect on whole cell K+ currents in SMA myocytes (data not shown). To confirm the activity of the toxin we heterologously expressed Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 channels in CHO cells (31) and found that K+ current in the former but not the latter was inhibited by 100 nmol/L α-dendrotoxin (data not shown). These results suggest that essentially all Kv1.2 subunits in SMA are present in heterotetrameric combination with Kv1.5 subunits but does not rule out the presence of homotetrameric Kv1.5 channels.

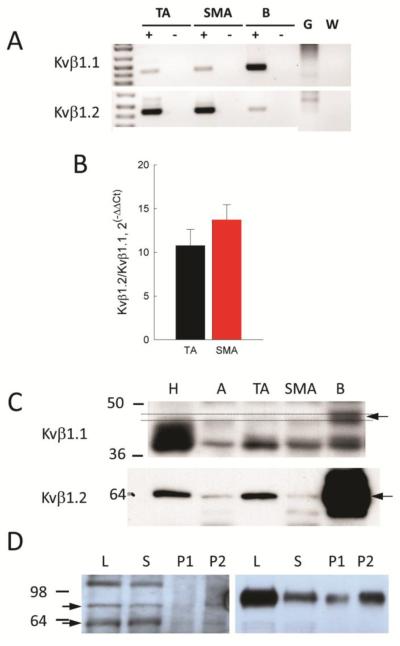

In many tissues, Kv1 α-subunits are associated with accessory β-subunits (6). We surveyed expression of the three gene families of Kvβ subunits by cPCR. We found mRNA expression for only Kvβ1.1 and β1.2 in ASMCs from SMA (Fig 4A) and compared the relative abundance of these two subunits by quantitative PCR (qPCR). When the expression of Kvβ1.2 was compared directly to that of Kvβ1.1 in the same samples by 2−ΔΔCt analysis, the ratio averaged 13.7 ± 1.7 (n=9) for SMA and 10.8 ± 1.9 (n=9) for TA (Fig 4B). When analyzed by Western blot of whole tissue lysates, only expression of Kvβ1.2 could be unequivocally detected in arterial protein lysates (Fig 4C). An association between Kvβ1.2 and Kv1.2 (and by implication with Kv1.5) could be demonstrated in both arterial and brain lysates by immunoprecipitation (Fig 4D). Combined, these results suggest that Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 are present as a heterotetramer along with Kvβ1.2 in SMA but the presence of homotetrameric Kv1.5 channels can not be ruled out.

FIGURE 4.

Kvβ1 accessory subunit expression in SMA myocytes. A: Agarose gel of Kvβ1.1 and β1.2 products amplified by cPCR from cellular RNA of TA and SMA along with brain (B), genomic DNA (G) and water (W) as additional templates. B: Kvβ1.1 and β1.2 expression in TA and SMA cells analyzed by qPCR, and represented as 2−ΔCCt directly compared in the same samples. C: Protein expression analyzed by Western blotting of tissue lyates from heart (H), aorta (A), TA, SMA and B. The arrow shows Kvβ1.1 expression in B but not in tissues, while Kvβ1.2 is expressed in all lysates. D: Association of Kvβ1.2 and Kv1.2 α-subunits in arterial (left panel) and brain lyates (right panel) shown by immunoprecipitation (IP). Arrows to the left show gylcosylated (80 kDa) and non-glycosylated (60 kDa) forms of Kv1.2 protein. Lanes are total lysate (L), supernatant (S), and P1 = 5 μl and P2 = 10 μl of the immunoprecipitated protein fractions.

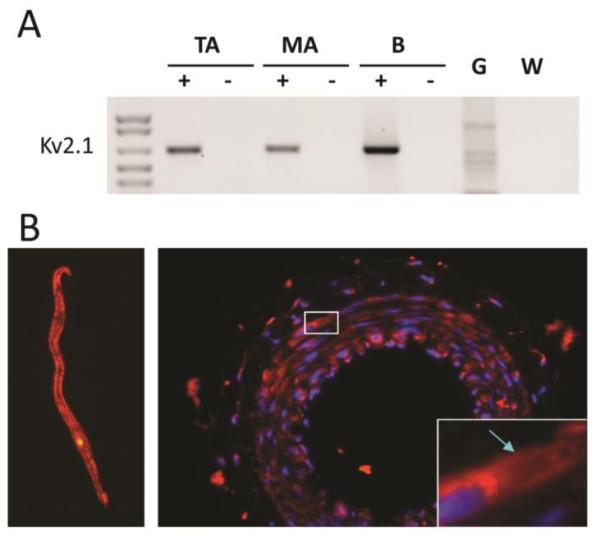

Next, we surveyed gene expression of Kv2 α-subunits in intact arteries (10,19,31) by cPCR using RNA isolated from ASMC of SMA as well as TA. We found expression of Kv2.1 but not Kv2.2 in ASMCs RNA (Fig 5A), and by immunofluorescence in both isolated cells and tissue sections (Fig. 5B). The latter shows the presence of Kv2.1 immunofluorescence in the adventitia as well as in the media of SMA suggesting expression of Kv2.1 in nerve terminals and/or fibroblasts as well as in ASMCs.

FIGURE 5.

Kv2.1 is expressed at the RNA and protein level in SMA myocytes. A: Agarose gel of cPCR products showing Kv2.1 expression in cellular RNA from TA and SMA as well as in B. B: Immunofluorescence detection of Kv2.1 in a myocyte (left) and in thin sections (right) of SMA showing cell surface expression of Kv2.1 (arrow).

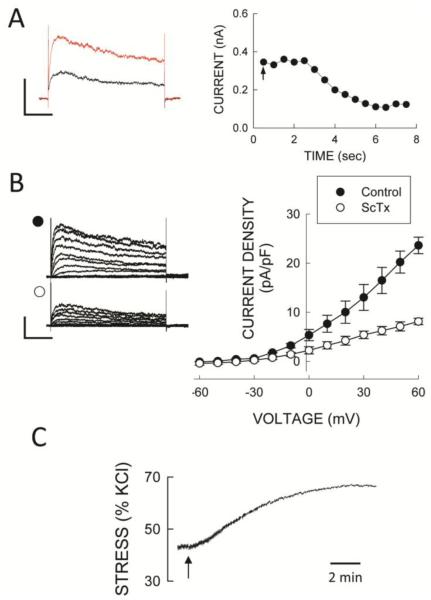

The contribution of Kv2.1 channels to whole cell Kv current was assessed using stromatoxin-1 (ScTx) a selective Kv2.1 inhibitor (36). Following inhibition of BKCa and CaV channels with IbTx and Nif, addition of l00 nmol/L ScTx produced a rapid inhibition of whole cell K+ current (Fig 6A,B) that averaged 48 ± 4% at +40 mV (n = 6). In addition, isolated SMA segments precontracted with 100 nmol/L phenylephrine or 30 nmol/L of a thromboxane A2 (PGH2) analog (U46619; Upjohn Co, Kalamazoo, MI) (36 ± 5% of the response to 120 mmol/L KCl) demonstrated robust contractions to ScTx (Fig 6C) that averaged 30 ± 8% of the response to 120 mmol/L KCL (n = 15). These results demonstrate that Kv2.1 channels also contribute to the regulation of contractile function in SMA myocytes.

FIGURE 6.

Kv2.1 channels are functional in SMA. A: Time course of 100 nmol/L stromatoxin (added at the arrow) inhibition of whole cell Kv current in an SMA cell. B: Whole cell current-voltage relations before and after ScTx in the presence of 100 nmol/L IbTx and 1μmol/L nifedipine in SMA myocytes. Symbols are mean values and vertical bars are ± 1 SEM (n=8). Voltage clamp protocols are as described in Figure 2. Horizontal and vertical calibration bars represent 100 pA in A and 200 pA in B, and 200 msec, respectively. C: Effect of ScTx (arrow) on wall stress (% of KCl) in SMA segment precontracted with 100 nmol/L PE. Horizontal bar is 2 min.

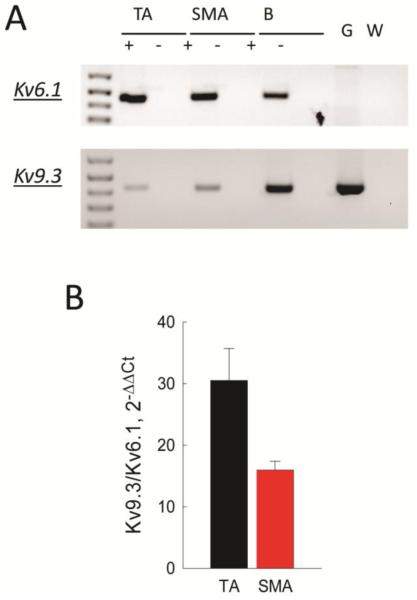

Kv2.1 subunits have been shown to associate with several accessory subunits that modify their biophysical properties as well as cell surface expression (4,37,38). We surveyed expression of accessory subunits known to associate with Kv2.1 and found expression of only Kv6.1 and Kv9.3 by cPCR (Fig 7A). We determined the relative abundance of these two transcripts by qPCR and found expression of Kv9.3 to be about 15 and 30 fold higher than Kv6.1 in SMA and TA, respectively (Fig 7B). We were unable to demonstrate protein expression of these two accessory subunits using commercially available antibodies by cellular IF, or by Western blotting using arterial lysates or lysates from HEK cells overexpressing V5-epitope tagged constructs of Kv6.1 and Kv9.3 subunits (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

Kv9.3 is the dominant Kv2.1 accessory subunit expressed in SMA myocytes. A: Agarose gel of Kv6.1 and Kv9.3 products amplified by cPCR from cellular RNA of TA and SMA. B: Kv6.1 and Kv9.3 expression in TA and SMA cells analyzed by qPCR, and represented as 2−ΔCCt directly comparing the ratio of expression in the same samples. Lines connect values that are significantly different (P < 0.05).

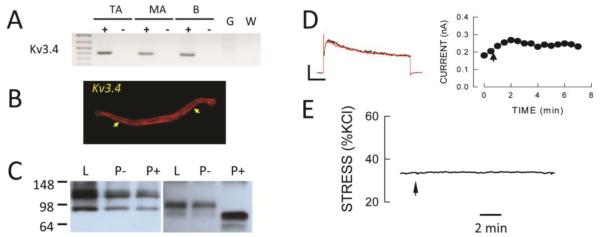

Previous studies suggested the presence of a rapidly inactivating, A-type Kv current in vascular myocytes (39). Some members of the Kv3 gene family have been shown to exhibit this phenotype so we surveyed expression of this Kv family by cPCR and found expression of only Kv3.4 in SMA and TA RNA (Fig 8A). Immunofluorescence suggested the presence of Kv3.4 immunoreactivity at the cell surface in SMA myocytes (Fig 8B) and Western blot analysis showed an immunoreactive protein band at a slightly larger size in arterial compared to brain lysates. Since mature Kv3.4 protein at the plasma membrane is glycosylated (40) we treated arterial and brain lystes with PNGase F which decreased the size of the protein in brain but had no effect on proteins in arterial lysates suggesting that the latter was not Kv3.4 protein (Fig 8C). More importantly, BDS-I and BDS-II, selective inhibitors of Kv3.4 channels (41), had no significant effect on whole cell Kv currents in SMA myocytes (Fig 8D) and no significant contractile effect in isolated SMA segments (Fig 8E). These results suggest that Kv3.4 channels if present are not functionally significant in SMA myocytes.

FIGURE 8.

Kv3.4 channels are not functionally expressed in SMA. A: Agarose gel shows cPCR products for Kv3.4 in cellular RNA from TA and SMA. B: Immunofluorescence showing plasma membrane localized immunoreactivity (arrows) with an anti-Kv3.4 antibody in SMA cells. C: PNGase-F treatment (P+) decreases the size of protein bands in brain (right panel) but not in arterial (left panel) lysates (L) or in lysates treated with buffer alone (P−). D: BDS-I (5 μmol/L has no effect on whole cell Kv current. Voltage clamp protocols are as described in Figure 2. Horizontal and vertical calibration bars represent 100 pA and 200 msec, respectively. E: BDS-I (5 μmol/L) has no effect on wall stress following pretreatment with 30 nmol/L U46619. Horizontal bar is 2 min.

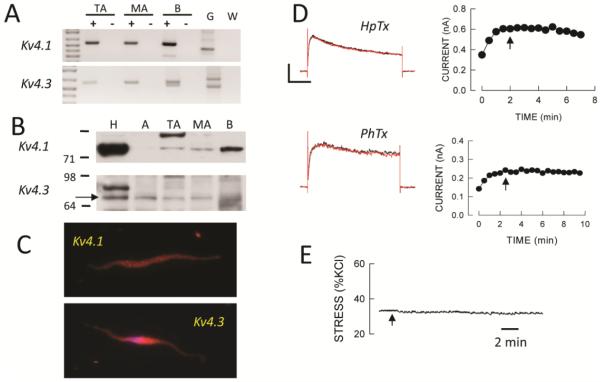

Members of the Kv4 gene family have also been shown to exhibit an A-current like phenotype so we also surveyed expression of members of this Kv family. We found expression of Kv4.1 and Kv4.3 by cPCR in RNA from SMA cells and by Western blot analysis of tissue lysates from LV, arteries and brain but not by cellular IF (Fig 9A-C). The 73 kD band considered to be Kv4.3 protein was insensitive to PNGase F as expected (42). However, toxin inhibitors of Kv4 channels, heteropodotoxin and phrixotoxin, had no significant effect on Kv currents in SMA myocytes (Fig. 9D), and heteropodotoxin had no contractile effect in isolated segments precontracted with phenylephrine (Fig 9E).

FIGURE 9.

Kv4 channels are not functionally expressed in SMA. A: Agarose gels showing expression of Kv4.1 and 4.3 in cellular RNA from TA and SMA by cPCR. B: Western blot suggesting expression of Kv4.1 and 4.3 in tissues as well as rat brain. C: Immunofluorescence showed no apparent plasma membrane expression of Kv4.1 or Kv4.3 in SMA myocytes. D: Neither heteropodotoxin (HpTx, 100 nmol/L) nor phrixotoxin (PhTx, 1 μmol/L) had an effect on whole cell Kv currents in SMA myocytes. Voltage clamp protocols are as described in Figure 2. Horizontal and vertical calibration bars represent 300 pA for HpTx and 120 pA for PhTx, and 200 msec, respectively. E: Heteropodotoxin had no effect on wall stress (% of KCl) in SMA precontracted with 30 nmol/L U46619. Horizontal bar is 2 min.

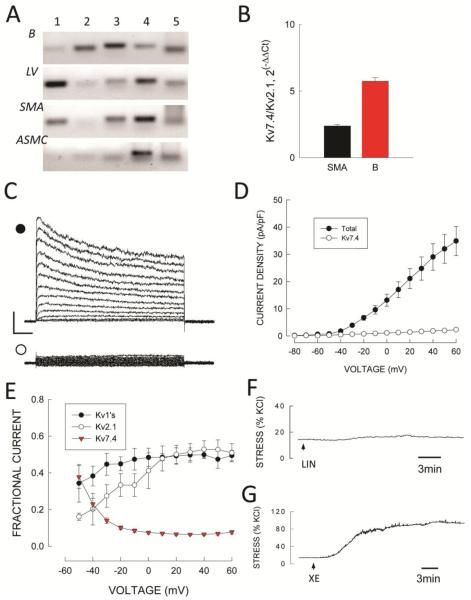

Recently, members of the KCNQ (Kv7) family have been shown to be expressed in vascular tissue and suggested to play a functional role (43,44). Accordingly, we surveyed expression of Kv7 family α-subunits in RNA from SMA. Using cPCR we found expression Kv7.1, 7.3, 7.4 and 7.5 in RNA from intact SMA (Fig. 11A) but only Kv7.4 and 7.5 in RNA isolated from ASMCs. By cPCR, expression of Kv7.1 and 7.4 was found in the left ventricular free wall and Kv7.2, 7.3, 7.4 and 7.5 expression was found in brain RNA. As Kv7.4 was the dominant transcript in myocyte RNA we compared its expression to that of Kv2.1 by qPCR. Expression of Kv2.1 was significantly larger than that of Kv7.4 in SMA myocyte RNA as well as in brain RNA (Fig. 10B).

FIGURE 10.

Kv7 channel expression in SMA. A: cPCR analysis of Kv7.1-7.5 subunit expression in RNA from brain (B), left ventricle (LV), intact arteries (SMA) and isolated SMA myocytes (ASMC). B: qPCR expression of Kv7.4 and Kv2.1 in SMA myocytes and brain and represented as 2−ΔCCt directly compared in the same samples. C: Total Kv (•) and Kv7.4 (○) currents in a SMA myocytes. Horizontal and vertical calibration bars represent 200 pA and 100 msec, respectively. D: Average values of peak Kv and Kv7.4 current density versus voltage. Symbols are mean values and vertical bars are ± 1 SEM (n=11). E: Relative amount of total Kv current of each component derived from experimental current data. Symbols are mean values and vertical bars are ±1 SEM. F/G. Effects of 10 μmol/L linopiridine (F, LIN) and 10 μmol/L XE-991 (G, XE) on wall stress (% KCl response) in SMA segments treated with 100 nmol/L phenylephrine plus 100 nmol/L iberiotoxin and 1μmol/L nifedipine. Horizontal bars represent 3 min.

Kv7.4 currents in SMA myocytes were determined by recording Kv current in the presence of 100 nmol/L IbTx, 1 μmol/L Nif, 10 μmol/L COR, l00 nmol/L ScTx and 1 mmol/L TEA after subtracting non-voltage dependent currents as described by Mackie et al (44). For the latter, currents recorded between −80 and −60 mV were extrapolated to all voltages representing non-voltage dependent, leak currents. Using such methods, Kv7.4 currents averaged 6.5 ± 1.5% of total Kv current at +40mV (Fig. 10C and D) but this value was strongly voltage dependent so that Kv7.4 accounted for about 40% of total Kv current at −50mV (Fig. 10E).

Finally, we used the selective inhibitor linopirdine to test for a functional role of Kv7.4 channels in SMA (43). Linopirdine (10 μmol/l) had no significant contractile effect under basal conditions (data not shown) and had only a small effect (7 ± 3 % of the KCl response) after treatment with 100 nmol/L phenylephrine in the presence of BKCa inhibition (Fig. 10F). A similar result was observed when segments were precontracted with 30 nmol/L U46619 (data not shown). In contrast, the Kv inhibitor XE-991 (10 μmol/L) (43) produced a large response equal to that of KCl under similar conditions (Fig. 10G).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate that functionally significant Kv channel complexes in SMA myocytes include heteromultimeric combinations of Kv1.2-Kv1.5-Kvβ1.2 and a likely combination of Kv2.1 with Kv9.3 subunits. The latter combination could not be unambiguously demonstrated at the protein level due to limitations in antibodies to test for the presence and association of Kv9.3 with Kv2.1 subunits. These two components account for 90-95% of total Kv current when recorded at high test voltages (+40mV), and contribute equally to total Kv current and to the regulation of arterial contraction in SMA. Kv7.4 channels are also functionally present in SMA and appear to provide a smaller contribution compared to the other two components but their contribution is strongly voltage dependent and at physiologically relevant voltages (−55 to −25 mV) (2) all three components contribute functionally.

Kv Subunit Expression

Since smooth muscle cells represent the most abundant cell type in arteries it would be expected that the expression profile of Kv subunits in SMA myocytes would be similar if not identical (at least qualitatively) to that of intact tissue. Indeed this expectation was confirmed in this study with high levels of expression of Kv1.2, 1.5, 2.1 and 7.4 α-subunits demonstrated in ASMCs. We also found expression of Kv1.1, 3.2b and 3.3 α-subunits in whole tissue RNA but not in ASMCs suggesting that these subunits may be expressed in other cell types in intact arteries (12).

Kvβ1.1 and β1.2 were the only Kvβ subunits expressed in SMA myocytes. qPCR showed that expression of Kvβ1.2 was more than an order of magnitude higher than that of Kvβ1.1 subunits. We found expression of Kvβ1.2 but not Kvβ1.1 by Western blotting in SMA lysates and found them to be associated with Kv1.2 by immunoprecipitation. Based upon the insensitivity of native Kv1 (ScTx-insensitive) currents to the Kv1.2 inhibitor α-dendrotoxin (35), these results suggest expression of a channel complex composed of Kv1.2-Kv1.5-Kvβ1.2 subunits in SMA myocytes, however, the stochiometry of the α/β association cannot be determined from these results.

Gene expression of Kv6.1 and Kv9.3 subunits known to associate with Kv2.1 (37,38) were found in RNA prepared from dispersed SMA myocytes with much higher levels of Kv9.3 expression. Although we could not confirm protein expression of Kv9.3 in this study, based upon electropysiological evidence presented in a companion study (45) it is highly likely that Kv2.1 subunits are associated with Kv9.3 subunits in SMA myocytes. In support of this conclusion, Zhong et al (20) recently showed plasma membrane expression of Kv9.3 as well as Kv2.1 subunits in rat middle cerebral artery myocytes using proximity ligation analysis to amplify signals from “weak” antibodies.

Functional Kv Channel Expression

Correolide (34) and stromatoxin (36), selective inhibitors of Kv1 and Kv2 channels, respectively, each inhibited about half of the total Kv current in SMA myocytes and produced quantitatively similar contractile responses in SMA segments confirming expression results. Selective inhibitors of Kv3 (heteropodatoxin and phriotoxin) and Kv4 channels (BDS-I and II) had no effect on Kv currents or on contraction in segments pretreated with either PE or a PGH2-analog which was surprising as we found evidence suggesting protein expression of Kv3.4, 4.1 and 4.3 α-subunits in SMA. It is possible that these subunits may not be trafficked to the plasma membrane, may be associated with inhibitory partners that prevent cell surface expression or activity, or may be post-translationally modified in a manner that inhibits functional activity (7,8,46,47). Alternatively, these may be false positive results due to limitations in reagents used which is likely the case with Kv3.4 subunits.

Members of the KCNQ gene family have been reported in several arteries of mouse, rat and human (15,16,48). Most studies agree that Kv7.4 is the most abundant transcript with expression of Kv7.4 protein primarily demonstrated by immunofluorescence in dispersed myocytes, and by pharmacological responses of cells or segments (16,43). Our results show expression of KCNQ4 transcripts in SMA myoyctes at lower levels compared to Kv2.1 subunits and a smaller contribution to functional activity of Kv7.4 channels compared to Kv1 and Kv2.1 channels. This finding seems at odds with the comparative results shown in Figure 11E but the contribution of Kv7.4 containing channels to total Kv current decreases rapidly with increasing (depolarized) voltages. Since agonist mediated depolarizations may reach values close to −20mV, this may be an explanation for the apparent smaller contribution of Kv7.4 channels in precontracted segments (2).

It is interesting that for the most part significant effects have been observed with Kv7 activators rather than inhibitors but some of the latter studies were performed using XE-199 which is now known to be nonselective. This is somewhat similar to the effects of KATP channels in arteries: small effects of inhibitors (depending upon conditions) but large effects of activators. This suggests that Kv7 channels may be more important in vasodilation associated with local (tissue) regulation of blood flow for example. It is likely that regional and species differences along with differences in experimental conditions contribute to these observations.

Physiological Significance

The results of the present study suggest that Kv1.2-1.5-β1.2 and Kv2.1-Kv9.3 subunit combinations are the dominant Kv components in SMA with Kv7.4 channels providing a smaller but functionally significant contribution that decrease with depolarization above −50 mV. Since there is some overlap in the biophysical properties of these channel complexes (4,15,21,49) as well as their contribution to cell function (e.g., myogenic regulation) (19,43,50) the question arises as to why the apparent redundancy? Many cell types such as cardiac myocytes express multiple Kv channel complexes but they usually subserve different aspects of cell function (51,52). This redundancy in ASMC may be important because mutations and/or epigenetic modifications of a single Kv gene or its protein product that cause loss-of-function could compromise arterial regulation as they do in the heart (52,53). Since Kv1 and Kv2.1 as well as Kv7.4 containing channels contribute to the regulation of smooth muscle contraction including myogenic responses, loss of function of one without a commensurate increase in the others would theoretically lead to vasoconstriction and loss of vasodilator reserve which would be prohypertensive but would not result in complete loss of Kv functionality in ASM.

The apparent redundancy may also be important by increasing the repertoire of cellular regulatory mechanisms. For example, only Kv1.5 possesses PKG consensus regulatory sequences while both Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 but not Kv2.1 contain N-linked glycosylation sites (Prosite, http://ca.expasy.org/prosite/). Both of these post-translational mechanisms have been shown to influence channel functional properties (54,55). Further, Kvβ1.2 is sensitive to redox conditions while Kvβ1.3 is not (56), and Kv7.4 is the target for perivascular adipose tissue-released regulatory mediators and hydrogen sulfide (57).

Study Limitations

There are several potential limitations that could affect the conclusions of this study. For one, antibodies have potential limitations that must be considered. The sensitivity and selectively of the antibodies used to detect Kv subunits herein have been validated by both cell immunofluorescence and Western blot using CHO or HEK cells stably expressing these channels some of which were V5 tagged (31). Kvβ1 antibodies were also tested using protein lysates from hearts of Kvβ1 knock-out and control mice (kindly supplied by Dr. J M Nerbonne, Washington Univ.). For other Kv subunits, the antibodies have been evaluated primarily by the presence of protein bands in Western blots at the size expected for either the translated product or post-translationally modified ones based upon a) citations in the literature or in protein data bases (http://www.expasy.org/) and b) by its presence in tissues (brain and/or left ventricle) where expression status has been confirmed. Although these are not the best criteria, they represent necessary tests.

We have used total tissue lysates to test for the presence of Kv subunits by Western blot. The small amount of arterial tissue from the rat makes it difficult to obtain sufficient protein mass from dispersed cells without pooling from an unacceptably large number of animals. Expanding isolated cells in culture is also unacceptable due to phenotypic modulation that occurs under such conditions (58). Proteins from sources other than smooth muscle cells may contribute to the total protein population in these lysates but smooth muscle cells are the most abundant cell type in resistance arteries so results are less likely to produce false positives. However, this approach does not discriminate between subcellular locations of Kv subunits and may overestimate plasma membrane (functional) levels. It was not the goal of this study to characterize subcellular distribution but rather to demonstrate expression of Kv subunits at the protein level in tissue lysates as a part of the total study of gene, protein and functional expression. Notably, all conclusions concerning protein expression are supported by functional studies.

Since Kv2.1 appears to be expressed in the adventitia, perhaps in nerve terminals, ScTx could potentially release transmitter from those terminals that could contribute to the contrtactile response. In these studies we used both phenylephrine and U44619 as agonists to precontract isolated arterial segments and the relative inhibitory effect of the two agonists was not significantly different (data not shown). While a contribution of transmitter release from perivascular nerves with ScTx may be present would be unlikely to alter the conclusions of the study.

Selective inhibitors of Kv channel subunits were used to determine their contributions to total Kv current as well as for their ability to modulate contractile function of isolated segments. In general, the inhibitors employed are accepted to be selective for specific α subunits and were used at levels 4-10 fold higher than their reported IC50. It would have been desirable to generate a dose-response relation for channel inhibitors to determine maximal efficacy but this was not practical. The effects of some inhibitors such as correolide require a substantial amount of time to achieve a steady state response. In general, it is difficult to maintain stability and quality of voltage clamped myocytes for the time required to perform such an analysis. For inhibitors constituted in organic solvents (e.g., DMSO) dilutions into the perfusion solution were never less than 1000:1 and the effects of solvent were always tested independently as a control.

Some studies have used the K+ channel inhibitor XE-199 to identify Kv7.4 currents in arteries. However, Zhong et al (43) have shown that this compound inhibits Kv1.2, 1.5 and 2.1 in addition to Kv7.4 channels. This is likely the reason that XE-199 produced a contractile response equal to that of 140 mmol/L KCl which was much larger than that produced by the selective Kv7.4 channel inhibitor linopiridine (Fig 10).

Finally, segments maintained under isometric conditions were used for contractile studies as opposed to pressurized segments. While less physiological, isometric preparations provide a similar (although different) view of the effect of Kv channel inhibitors on smooth muscle contractile function (59). It is unlikely, that these two preparations would yield qualitatively different conclusions with regard to the effects of inhibitors on contractile function. However, it is difficult to reconcile data presented in Figure 10. We show that linopiridine produces only a small increase in contraction in the presence of a submaximal concentration of phenylephrine (Fig. 10F). However, at more negative voltages makes a substantial contribution to whole cell K+ currents (Fig 10C). The reason for this discrepancy is not clear but may be related to the actual membrane potential of arterial cells prior to addition of phenylephrine which is not known.

In summary, on the basis of studies including mRNA and protein expression, immunofluorescence, measurements of Kv current and contractile responses to selective inhibitors we have shown that three Kv subunit complexes dominate functional Kv channels in myocytes from small mesenteric arteries of the rat. One is a combination of Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 α-subunits with Kvβ1.2 subunits, and another Kv2.1 α-subunits probably associated with Kv9.3 accessory subunits. Kv7.4 containing channels are also functionally present but it is not clear if they are associated with other KCNQ family members (eg., Kv7.5) or with accessory subunits which has been reported (60).

Acknowledgments

Supported by HL28476 from USPHS

REFERENCES

- 1.Nelson MT, Quayle LM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. (1995) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stekiel WJ. Electrophysiological mechanisms of force development by vascular smooth muscle membrane in hypertension. In: Lee RMKW, editor. Blood Vessel Changes in Hypertension: Structure and Fucntion: Vol II. CRC Press, Inc.; Boca Raton FL: 1989. pp. 127–170. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson MT, Patlak JB, Worley JF, Standen NB. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C3–C18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.1.C3. (1990) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox RH. Molecular determinants of voltage gated potassium currents in vascular smooth muscle. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2005;42:167–195. doi: 10.1385/CBB:42:2:167. (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Um SY, McDonald TV. Voltage-gated potassium channels: regulation by accessory subunits. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:199–210. doi: 10.1177/1073858406287717. (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres YP, Morera FJ, Carvacho I, Latorre R. A marriage of convenience: β-subunits and voltage-dependent K+channels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24485–24489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700022200. (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, Chow A, Lau D, McCormick T, Moreno H, Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Poutney D, Sagamich M, De Miera E, Rudy B. Molecular diversity of K+ channels. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;868:233–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x. (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandy KG, Gutman GA. Voltage-gated potassium channels, in Handbook of Receptors and Channels. In: North RA, editor. Ligand and Voltage-Gated Ion Channels. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1994. pp. 1–71. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fergus DJ, Martens JR, England SK. Kv channel subunits that contribute to voltage-gated K+ current in renal vascular smooth muscle. Pflugers Arch. 1998;445:697–704. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0994-7. (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan XJ, Wang J, Juhaszova M, Golovina VA, Rubin LJ. Molecular basis and function of voltage-gated K+ channels in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 2003;274:L621–L635. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.4.L621. (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorneloe KS, Chen TT, Grier EF, Horowitz B, Cole WC, Walsh MP. Molecular composition of 4-aminopyridine-sensitive voltage-gated K+ channels of vascular smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2001;9:1030–1037. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100817. (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheong A, Dedman AM, Xu SZ, Beech DJ. Kvα1 channels in murine arterioles: differential cellular expression and regulation of diameter. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:H1057–H1065. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H1057. (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu C, Lu Y, Tang G, Wang R. Expression of voltage-dependent K+ channel genes in mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G1055–G1063. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.5.G1055. (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGahon MK, Dawicki JM, Arora A, Simpson DA, Gardiner TA, Stitt AW, Scholfield CN, McGeown JG, Curtis TM. Kv1.5 is a major component underlying the A-type potassium current in retinal arteriolar smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:H1001–H1008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01003.2006. (2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackie AR, Brueggemann LI, Henderson KK, Shiels AJ, Cribbs LL, Scrogin KE, Byron KL. Vascular KCNQ potassium channels as novel targets for the control of mesenteric artery constriction by vasopressin, based on studies in single cells, pressurized arteries, and in vivo measurements of mesenteric vascular resistance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:475–483. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135764. (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng FL, Davis AJ, Jepps TA, Harhun MI, Yeung SY, Wan A, Reddy M, Melville D, Nardi A, Khong TK, Greenwood IA. Expression and function of the K+ channel KCNQ genes in human arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:42–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01027.x. (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu Y, Zhang J, Tang G, Wang R. Modulation of voltage-dependent K+ channel current in vascular smooth muscle cells from rat mesenteric arteries. J Membrane Biol. 2001;180:163–175. doi: 10.1007/s002320010067. (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albarwani S, Nemetz LT, Madden JA, Tobin AA, England SK, Pratt PF, Rusch NJ. Voltage-gated K+ channels in rat small cerebral arteries: molecular identity of the functional channels. J Physiol. 2003;551:751–763. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040014. (2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amberg GC, Santana LF. Kv2 channels oppose myogenic constriction of rat cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:C348–C356. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00086.2006. (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong XZ, Abd-Elrahman KS, Liao CH, El-Yazbi AF, Wash EJ, Walsh MP, Cole WC. Stromatoxin-sensitive, heteromultimeric Kv2.1/Kv9.3 channels contribute to myogenic control of cerebral arterial diameter. J Physiol. 2010;588:4519–4537. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.196618. (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grissmer S, Nguyen AN, Aiyar J, Hanson DC, Mather RJ, Gutman GA, Karmilowicz MJ, Auperin DD, Chandy KG. Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated channels, types Kv1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5 and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:1227–1234. (1994) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colinas O, Gallego M, Setien R, Lopez-Lopex JM, Perez-Garcia MT, Casis O. Diffferential modulation of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 channels by calmodulin-dependent protein kinse II in rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:H1978–H1987. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01373.2005. (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu Z, Abe J, Taunton J, Lu Y, Shishido T, McClain C, Yan C, Xu SP, Spangenberg TM, Xu H. Reactive oxygen species-induced activation of p90 ribosomal S6 kinase prolongs cardiac repolarization through inhibiting outward K+ channel activity. Circ Res. 2008;103:269–278. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.166678. (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Um SY, McDonald TV. Voltage-gated potassium channels: regulation by accessory subunits. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:199–210. doi: 10.1177/1073858406287717. (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bett GC, Rasmusson RL. Modification of K+ channel-drug interactions by ancillary subunits. J Physiol. 2008;586:929–950. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139279. (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelband CH, Hume JR. (Ca2+)i inhibition of K+ channels in canine renal artery. Novel mechanism for agonist-induced membrane depolarization. Circ Res. 1995;77:121–130. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.121. (1995) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox RH, Petrou S. Ca(2+) influx inhibits voltage-dependent and augments Ca(2+)-dependent K(+) currents in arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C51–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.1.C51. (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brignell JL, Perry MD, Nelson CP, Willets JM, Challiss RA, Davies NW. Steady-state modulation of voltage-gated K+ channels in rat arterial smooth muscle by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and protein phosphatase 2B. PLoSOne. 2015;10(3):e0121285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121285. (2015) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fishman JA, Ryan GB, Karnovsky MJ. Endothelial regeneration in the rat carotid artery and the significance of endothelial denudation in the pathogenesis of myointimal thickening. Lab Invest. 1975;32:339–351. (1975) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox RH, Folander K, Swanson R. Differential expression of voltage-gated K+ channel genes in arteries from spontaneously hypertensive and Wistar-Kyoto rats. Hypertension. 2001;37:1315–1322. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1315. (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cox RH, Fromme S, Folander K, Swanson RR. Voltage gated K+ channel expression in arteries of Wistar Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Hyperten. 2008;21:213–218. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.44. (2008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox RH, Haas KS, Moisey DM, Tulenko TN. Effects of endothelium regeneration on canine coronary artery function. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H1681–H1692. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.5.H1681. (1989) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Felix JP, Bugianesi RM, Schmalhofer WA, Borris R, Goetz MA, Hensens OD, Bao J-M, Kayser F, Parsons WH, Rupprecht K, Garcia ML, Kaczorowski GJ, Slaughter RS. Identification and biochemical characterization of a novel nortriterpene inhibitor of the human lymphocyte voltage-gated potassium channel, Kv1.3. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4922–4930. doi: 10.1021/bi982954w. (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell SN, Overturf KE, Horowitz B. Heterotetramer formation and charybdotoxin sensitivity of two K+ channels cloned from smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C1729–C1733. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.6.C1729. (1994) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Escoubas P, Diochot S, Célérier ML, Nakajima T, Lazdunski M. Novel tarantula toxins for subtypes of voltage-dependent potassium channels in the Kv2 and Kv4 subfamilies. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:48–57. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.48. (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel AJ, Lazdubski M, Honore E. Kv2.1/Kv9.3, a novel ATP-dependent delayed-rectifier K+ channel in oxygen-sensitive pulmonary artery myocytes. EMBO Journal. 1997;6:6615–6625. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.22.6615. (1997) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kramer JW, Post MA, Brown AM, Kirsch GE. Modulation of potassium channel gating by coexpression of Kv2.1 with regulatory Kv5.1 or Kv6.1 alpha-subunits. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1501–C1510. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1501. (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amberg GC, Koh SD, Imaizumi Y, Ohya S, Sanders KM. A-type potassium currents in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:C583–C595. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00301.2002. (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cartwright TA, Corey MJ, Schwalbe RA. Complex oligosaccharides are N-linked in Kv3 voltage-gated K+ channels in brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:666–671. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.11.013. (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diochot S, Schweitz H, Béress L, Lazdunski M. Sea anemone peptides with a specific blocking activity against the fast inactivating potassium channel Kv3.4. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6744–6749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6744. (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Birnbaum SG, Varga AW, Yuan LL, Anderson AE, Sweatt JD, Schrader LA. Structure and function of Kv4-family transient potassium channels. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:803–833. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2003. (2004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhong XZ, Harhun MI, Olesen SP, Phya S, Moffatt JD, Cole WC, Greenwood IA. Participation of KCNQ (Kv7) potassium channels in myogenic control of cerebral artery diameter. J Physiol. 2010;588:3277–3293. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192823. (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mackie AR, Brueggemann LI, Henderson KK, Shiels AJ, Cribbs LL, Scrogin KE, Byron KL. Vascular KCNQ potassium channels as novel targets for the control of mesenteric artery constriction by vasopressin, based on studies in single cells, pressurized arteries, and in vivo measurements of mesenteric vascular resistance. J Pharmacol ExpTher. 2008;325:475–83. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135764. (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cox RH, Fromme S. Comparison of voltage gated K+ currents in arterial myocytes with Kv subunits expressed in HEK293 cells. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12013-016-0763-4. 2015. Submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Misonou H, Trimmer JS. Determinants of voltage-gated potassium channel surface expression and localization in mammalian neurons. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:125–145. doi: 10.1080/10409230490475417. (2004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bocksteins E, Snyders DJ. Electrically silent Kv subunits: Their molecular and functional characteristics. Physiology. 2012;27:73–84. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00023.2011. ((2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeung SY, Pucovský V, Moffatt JD, Saldanha L, Schwake M, Ohya S, Greenwood IA. Molecular expression and pharmacological identification of a role for K(v)7 channels in murine vascular reactivity. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:758–770. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707284. (2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miceli F, Cilio MR, Taglialatela M, Bezanilla F. Gating currents from neuronal K(V)7.4 channels: general features and correlation with the ionic conductance. Channels (Austin) 2009;3:274–2783. (2009) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plane F, Johnson R, Kerr P, Wiehler W, Thorneloe K, Ishii K, Chen T, Cole W. Heteromultimeric Kv1 channels contribute to myogenic control of arterial diameter. Circ Res. 2005;96:216–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000154070.06421.25. (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nerbonne JM. Regulation of voltage-gated K+ channel expression in the developing mammalian myocardium. J Neurobiol. 1998;37:37–59. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199810)37:1<37::aid-neu4>3.0.co;2-9. (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmitt N, Grunnet M, Olesen S-P. Cardiac potassium channel subtypes: new roles in repolarization and arrhythmia. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:609–653. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2013. (2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulz DJ, Temporal S, Barry DM, Garcia ML. Mechanisms of voltage-gated ion channel regulation: from gene expression to localization. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2215–2231. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8060-z. (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Núñez L, Vaquero M, Gómez R, Caballero R, Mateos-Cáceres P, Macaya C, Iriepa I, Gálvez E, López-Farré A, Tamargo J, Delpón E. Nitric oxide blocks hKv1.5 channels by S-nitrosylation and by a cyclic GMP-dependent mechanism. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.021. (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watanabe I, Zhu J, Sutachan JJ, Gottschalk A, Recio-Pinto E, Thornhill WB. The glycosylation state of Kv1.2 potassium channels affects trafficking, gating, and simulated action potentials. Brain Res. 2007;1144:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.092. (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Z, Kiehn J, Yang Q, Brown AM, Wible BA. Comparison of binding and block produced by alternatively spliced Kvβ1 subunits. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28311–28317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28311. (1996) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schleifenbaum J, Köhn C, Voblova N, Dubrovska G, Zavarirskaya O, Gloe T, Crean CS, Luft FC, Huang Y, Schubert R, Gollasch M. Systemic peripheral artery relaxation by KCNQ channel openers and hydrogen sulfide. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1875–1882. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833c20d5. (2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuan XJ, Goldman WF, Tod ML, Rubuin LJ, Blaustein MP. Ionic currents in rat pulmonary and mesenteric arterial myocytes in primary culture and subculture. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:L107–L115. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.2.L107. (1993) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cox RH. Contribution of smooth muscle to arterial wall mechanics. Basic Res Cardiol. 1979;74:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01907680. (1979) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strutz-Seebohm N, Seebohm G, Fedorenko O, Baltaev R, Engel J, Knirsch M, Lang F. Functional coassembly of KCNQ4 with KCNE-beta- subunits in Xenopus oocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2006;18:57–66. doi: 10.1159/000095158. (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]