Abstract

This study examines how the intersecting consequences of race-ethnicity, gender, socioeconomics status (SES), and age influence health inequality. We draw on multiple-hierarchy stratification and life course perspectives to address two main research questions. First, does racial-ethnic stratification of health vary by gender and/or SES? More specifically, are the joint health consequences of racial-ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic stratification additive or multiplicative? Second, does this combined inequality in health decrease, remain stable, or increase between middle and late life? We use panel data from the Health and Retirement Study (N = 12,976) to investigate between- and within-group differences in in self-rated health among whites, blacks, and Mexican Americans. Findings indicate that the effects of racial-ethnic, gender, and SES stratification are interactive, resulting in the greatest racial-ethnic inequalities in health among women and those with higher levels of SES. Furthermore, racial-ethnic/gender/SES inequalities in health tend to decline with age. These results are broadly consistent with intersectionality and aging-as-leveler hypotheses.

Keywords: aging and life course, gender, health disparities, race-ethnicity, stratification

As key dimensions of social stratification, race- ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status (SES) structure differential access to resources, exposure to risks, and life chances—including health. Indeed, racial-ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic inequalities in health are hallmarks of the U.S. population’s health profile. Blacks and Mexican Americans experience higher rates of morbidity than whites (Brown, O’Rand, and Adkins 2012; Williams and Mohammed 2013). Although women have lower mortality rates than men, they often exhibit worse health (Bird and Rieker 2008; Read and Gorman 2010). Furthermore, there is a well-established SES gradient in health: health worsens as economic disadvantage increases (House, Lantz, and Herd 2005; Link and Phelan 1995). In addition to lost years and quality of life, these health inequalities carry significant economic costs due to excess health care spending and reduced labor market productivity (LaVeist, Gaskin, and Richard 2011). This toll is likely to increase over the next several decades, given several population trends—for example, the aging baby boom cohort, rising life expectancies, and increasing racial-ethnic diversity of the older population. Between 2010 and 2030, the older population—the majority of whom are women—is projected to increase from 40 to 72 million, with the proportions of older blacks and Hispanics increasing by 17% and 67%, respectively (Vincent and Velkoff 2010). These trends make it imperative that we examine the influence of race-ethnicity, gender, and SES on health inequalities in the context of aging.

While health inequalities among racial-ethnic, gender, and SES groups have been well documented independently (e.g., Link and Phelan 1995; Read and Gorman 2010; Williams and Mohammed 2013), few studies have examined how the intersection of these dimensions of stratification influences health trajectories. The conventional, unidimensional approach to studying the social stratification of health has been to examine how an individual’s position in a single status hierarchy affects well-being. For example, sociologists studying racial-ethnic inequality in health infrequently consider how it may be gendered and vice versa. Even fewer studies have examined the potentially synergistic effects of race-ethnicity, gender, and SES. Intersectionality and other multiple-hierarchy stratification scholars have cogently argued that examining inequalities along racial-ethnic, gender, and SES lines separately masks their intersecting consequences and essentializes race-ethnicity and gender (Collins 2000; Clark and Maddox 1992; Davis 1981; McCall 2005; Schulz and Mullings 2006). Furthermore, the few studies that have explored the joint health consequences of these social factors have assumed that they are additive. This assumption, while an improvement over unidimensional approaches, obscures the potentially multiplicative effects of social statuses on health inequality posited by intersectionality scholars.

Another limitation of previous research on how multiple dimensions of inequality jointly affect health has been the scant attention to the patterning of this effect as individuals age. Although age stratification and life course perspectives emphasize age as a dimension of inequality (Dannefer 2003; Ferraro, Shippee, and Schafer 2009; O’Rand and Henretta 1999; Pavalko and Caputo 2013; Willson, Shuey, and Elder 2007), few studies have examined whether health inequalities along racial-ethnic, gender, and SES lines (and their intersections) decrease, remain stable, or increase with increasing age (for exceptions, see Ailshire and House 2011; Clark and Maddox 1992). Instead, they have tacitly assumed that the relationships among race-ethnicity, gender, SES, and health do not vary with age. If this assumption is incorrect, then the prevailing practice of ignoring how race-ethnicity, gender, SES, and age intersect has grossly limited our understanding of the dynamic nature of health inequality over time.

This study aims to challenge this assumption and extend previous research on health stratification by examining the intersecting consequences of race-ethnicity, gender, SES, and age on health inequities in middle and late life. We draw on multiple-hierarchy stratification and life course perspectives to better understand the social distribution of health over time, focusing on two main research questions. First, does racial-ethnic stratification of health vary by gender and/or class? More specifically, are the joint health consequences of racial-ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic stratification additive or multiplicative? Second, does this combined inequality in health decrease, remain stable, or increase between middle and late life?

To answer these questions, we investigated between- and within-group differences in self-rated health among non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Mexican American men and women. By using a multiple-hierarchy approach to health stratification within a life course framework, we found that racial-ethnic inequality in self-rated health is gendered and classed. Specifically, we found that racial-ethnic health inequality is greatest among women and those with higher levels of SES. Moreover, racial-ethnic minorities—especially women of color—experience diminished heath returns to socioeconomic resources. In addition, health stratification along racial-ethnic, gender, and SES lines are dynamic over time, most often declining with age. Thus, this study provides a better understanding of the joint and long-term health consequences of racial-ethnic, gender, and SES stratification.

BACKGROUND

Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health

The association between SES and health is well established in the literature. Studies have consistently shown than health differs by social standing, with those at the lower end of the socioeconomic hierarchy—that is, with less education, income, wealth, or occupational prestige—tending to have worse health than their higher-status counterparts (Link and Phelan 1995; Marmot 1991; Willson et al. 2007). The reason for this robust relationship is that socioeconomic factors at individual, household, and neighborhood levels structure both exposure to risk factors for poor health and access to protective factors (Braveman et al. 2005; House et al. 2005). Beyond shaping an individual’s access to tangible health-promoting resources, such as quality food and medical care, SES also influences knowledge, power, and other resources that are needed to avoid risk or the negative consequences of exposure to risk (Link and Phelan 1995).

Racial-ethnic Inequalities in Health

Black–white inequalities in health are well documented, revealing a consistent pattern of black health disadvantage. Blacks have worse self-rated health (Cummings and Jackson 2008; Yang and Lee 2009) and elevated rates of hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, functional limitations, and mortality compared to whites (Farmer and Ferraro 2005; Haas and Rohlfsen 2010; Hummer et al. 2000; Pleis, Ward, and Lucas 2010). However, evidence regarding health inequality between Mexican Americans and whites is mixed. Mexican Americans report worse self-rated health; suffer from higher rates of diabetes, kidney, and liver disease; and have more functional limitations than whites (Markides et al. 1997; Pleis et al. 2010; Shetterly et al. 1996). Conversely, Mexican Americans have lower rates of hypertension and cancer than whites and comparable rates of mortality (Hummer et al. 2000; Pleis et al. 2010). These mixed findings regarding Mexican Americans’ health may be due, on the one hand, to the large proportion of recent Mexican immigrants who have better health profiles than U.S.-born whites and Mexican Americans with longer durations of U.S. residence (Markides et al. 2007) and, on the other hand, to the fact that. U.S.-born Mexican Americans tend to have worse health than their white counterparts (Hayward, Warner, and Crimmins 2007).

The prevailing approach to research on the mechanisms underlying racial-ethnic inequalities in health has been to focus on racial-ethnic differences in SES, health behavior, and medical care. However, these differences do not fully account for racial-ethnic inequalities in health (Cummings and Jackson 2008; Hayward et al. 2000). Sociologists have long recognized the possibility that an array of factors stemming from institutional and interpersonal racism contribute to health disparities (Du Bois 1899). Indeed, there is growing evidence that residential segregation and discrimination across the life course play key roles in racial-ethnic health inequalities (Gee and Ford 2011; Thoits 2010; Williams and Mohammed 2013).

Gender Inequalities in Health

The population health literature has long shown that health varies by gender. Although women live longer than men, they have higher morbidity rates and diminished quality of life (Bird and Rieker 2008). Previous studies show that compared to men, women have worse self-rated health (Idler 2003; Yang and Lee 2009), more nonfatal chronic conditions, and greater likelihood of functional limitations (Read and Gorman 2010; Verbrugge 1985). These differences may be partially due to gendered social roles and expectations (Bird and Rieker 2008). For example, scholars have noted the effects of hegemonic masculinity on men’s health behaviors—for example, risk taking, substance abuse, and avoidance of medical care—which may help explain their shorter life expectancy despite lower morbidity rates (Courtenay 2000). More commonly, the poorer health of women relative to men has been attributed to women’s lower SES, though differences in SES do not fully explain the gender gap in health (Read and Gorman 2010). Thus, recent scholarship on gender inequalities in health theorizes that women’s health disadvantage stems from women’s greater stress exposure, as well as their constrained choices, due to institutional and family arrangements (Bird and Rieker 2008; Thoits 2010).

Multiple-hierarchy Stratification Perspectives on Health Inequality

Although racial-ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic inequalities in health are well documented, little is known about how the combination of these dimensions of stratification (and others) shapes health. Filling this gap requires application of the multiple-hierarchy stratification perspective (Clark and Maddox 1992; Grollman 2014; Jeffries and Ransford 1980; Schieman and Plickert 2007), which seeks to understand how ascribed and achieved statuses interact over the life course to shape life chances, including health. This perspective, therefore, reflects one of the most central tenets of sociology—that is, that life chances are shaped by a constellation of social factors (Weber [1922] 1946). This study focuses on the intersecting consequences of race-ethnicity, gender, and SES, given their well-established and robust associations with health. Moreover, these three statuses are regarded as the “holy trinity of stratification” and are readily observed in society and used by others to evaluate individuals (Massey 2007). Below we consider two alternative multiple-hierarchy stratification perspectives: multiple jeopardy and intersectionality. Each of these frameworks is informed by black feminism (Collins 2000) and critical race feminist theories (Few 2007) and generates different hypotheses about how race-ethnicity, gender, and SES combine to stratify health outcomes.

The multiple jeopardy hypothesis predicts that as a consequence of the additive effects of race-ethnicity, gender, and SES, white men of high SES would enjoy the best health, low-SES black and Mexican American women would experience the worst health outcomes, and other race/gender/SES groups would fall somewhere in between these extremes.1 In other words, the health disadvantages experienced by poor black and Mexican American women are the sum of those associated with being poor, those associated with being a woman, and those associated with being black/Mexican American (Beal 1970). Such additive models have been criticized for failing to consider pertinent differences in the contexts within which white versus nonwhite women experience sexism, minority men versus minority women experience racism, and all racial-ethnic/gender groups experience capitalism (Weber 2010). It is, therefore, limited in its ability to capture multiple-hierarchy stratification because it reinforces the notion that these social statuses are independent dimensions of stratification (King 1988).

The intersectionality hypothesis responds to this critique of the multiple jeopardy hypothesis by positing that black and Mexican American women are likely to be especially disadvantaged because dimensions of inequality interact in multiplicative ways, resulting in unique social contexts that condition the lived experiences and life chances of the individuals situated within those contexts (Collins 2000; Choo and Ferree 2010; Hinze, Lin, and Andersson 2012). In other words, a key premise of intersectionality is that racial-ethnic, gender, and SES stratification are both simultaneous and interactive (Ailshire and House 2000; Brown and Hargrove 2013; Landry 2007), that is, “interlocking” (Dill and Zambrana 2009). Thus, rather than examining the effects of different social statuses separately, or assuming that the total disadvantage experienced by people with multiple disadvantaged statuses is equivalent to the sum of their disadvantages, intersectionality highlights the importance of examining the multiplicative effects of several social statuses on health (Choo and Ferree 2010; Veenstra 2013). Thus, an intersectionality hypothesis would predict that race-ethnicity, gender, and SES have nonadditive effects on health such that the health consequences of each of these social status dimensions are conditional upon each other. For example, it would predict that the magnitude of racial-ethnic health gaps will be greater among women than men, due to the compounding effects of racial-ethnic and gender inequality (Brown and Hargrove 2013). Similarly, an intersectionality perspective would predict that the SES–health gradient will be less steep among racial-ethnic minorities, women, and especially, minority women (Jackson and Williams 2006). Moreover, white men with high SES would be expected to have the best health, while black and Mexican American women with low SES would have the worst health, and other race-ethnicity/gender/SES groups would occupy liminal statuses (Schulz and Mullings 2006).

Evidence of Multiple-hierarchy Stratification of Health

Relatively few empirical studies have examined the combined effects of racial-ethnic, gender, and SES inequality on health. Among those that have, most have not explicitly tested whether their effects are additive or multiplicative. Rather, they have tended to use a “configurational” approach (Alon 2007), which typically compares race-ethnicity/gender combinations (e.g., black women, black men, white women) to one reference group (usually white men). Previous research using this approach has found that black and Mexican American women are disadvantaged relative to other racial-ethnic/gender groups in terms of health (Geronimus et al. 2007; Read and Gorman 2006; Warner and Brown 2011).

Of the few studies that have investigated whether the effects of social factors are additive or multiplicative, most have examined interactions between only two social statuses, have focused exclusively on blacks and whites, and have yielded mixed results. On the one hand, several studies appear to support the multiple jeopardy hypothesis. Hinze and colleagues (2012), for example, showed that the joint consequences of race and gender on self-rated health were additive among black and white adults with at least a high school education. In addition, Hayward and colleagues (2000) found no evidence of interactions between race and socioeconomic resources on prevalence of chronic conditions among older blacks and whites. On the other hand, findings from several studies indicated that race-ethnicity and gender combine in a multiplicative fashion, leading to greater racial-ethnic inequality in health among women than among men—consistent with the intersectionality hypothesis (Brown and Hargrove 2013; Hayward et al. 2000; Umberson et al. 2014). Moreover, Farmer and Ferraro (2005) found that race and education interact, resulting in a steeper education–health gradient among whites than among blacks and the largest black–white gap in health at higher levels of education. Furthermore, a study by Cummings and Jackson (2008) found evidence of an interaction between race–gender configurational position and educational attainment, which indicated that black women experience diminished self-rated health returns on education, relative to white men and women.

Due to these mixed findings and gaps in the literature, it remains unclear how race-ethnicity, gender, and SES combine to shape health outcomes. We aim to fill these gaps in the literature by testing the multiple jeopardy and intersectionality hypotheses. Based on the weight of the theoretical and empirical evidence discussed above, we hypothesize that the magnitude of racial-ethnic differences in health is greater among women than among men and greater among high-SES than among low-SES adults, leading black and Mexican American women with low SES to experience especially poor health. This hypothesis is indicative of interactive effects of race-ethnicity, gender, and SES on health, consistent with the intersectionality perspective.

Combining Multiple-hierarchy Stratification and Life Course Perspectives to Study Health Inequality

In addition to examining health inequality along racial-ethnic, gender, and SES lines, it is also important to consider whether and how the social stratification of health varies with age. Although age is recognized as a dimension of stratification (Riley, Johnson, and Foner 1972), there is debate in the health inequalities literature (and in inequality research writ large) about whether inequality decreases, remains stable, or increases with age (O’Rand and Henretta 1999). The aging-as-leveler hypothesis asserts that health inequality should decline with advancing age, leading to converging health trajectories, particularly after midlife (Brown et al. 2012; House et al. 2005). Two of the primary processes that result in leveling include (1) mortality selection, which leads to the most disadvantaged (and least healthy) groups being selected out of the sample, and (2) delayed onset and progression of illness due to the social and economic resources that advantaged groups possess, which effectively compresses their morbidity to later life, at which point they experience more rapid declines than disadvantaged groups. Both of these processes are likely to contribute to declining health inequalities at later ages (Dupre 2007). In the context of intersectionality, for example, the aging-as-leveler hypothesis would predict that racial-ethnic, gender, and SES inequality, as well as the multiplicative deleterious consequences associated with being a nonwhite woman of low SES, would decrease between middle and late life. Alternatively, the persistent inequality hypothesis posits that intracohort gaps in health are stable across the life course (Ferraro and Farmer 1996; Henretta and Campbell 1976). Thus, it predicts that health advantages and disadvantages will hold, with age neither equalizing nor amplifying the difference. Finally, the cumulative disadvantage hypothesis predicts that health trajectories of advantaged and disadvantaged individuals widen with age (Dannefer 2003; Pavalko and Caputo 2013). Individuals with initial advantages accumulate more resources and opportunities over time and are better able to avoid or allay health risks; disadvantages in early life precipitate subsequent disadvantages and risks as individuals age (Ferraro et al. 2009; Willson et al. 2007). In the case of intersectionality, the cumulative disadvantage hypothesis would predict that health inequalities along racial-ethnic, gender, and SES lines (and their intersections) would increase between middle and late life. Indeed, some evidence suggests that black women experience accelerated health deterioration or “weathering” with advancing age (Geronimus et al. 2007).

Due to limitations of previous studies, it is unclear which of these hypotheses apply to life course patterns of gendered and classed racial-ethnic health inequalities. First, few longitudinal studies of health inequalities have applied a multiple-hierarchy approach to racial-ethnic, gender, and class stratification. Rather, longitudinal health studies have largely analyzed the independent effects of race-ethnicity (Brown et al. 2012; Kim & Miech, 2009), gender (Anderson et al. 1998; Liang et al. 2008), or SES (Lantz et al. 2001; Ross and Wu 1996), and these unidimensional studies have yielded mixed evidence for the alternate life course hypotheses. Second, given that age inequality dynamics are likely to vary across life stages (e.g., early life, midlife, and late life; House et al. 2005), inconsistent support for the alternate life course hypotheses may be due to the fact that previous studies have tended to examine them using different age ranges. For these reasons, it remains unknown whether and how the simultaneity and interaction of race-ethnicity, gender, and SES advantages or disadvantages particular subgroups with respect to their health over the life course. There is, however, growing evidence that health inequality along single dimensions of stratification tends to peak in midlife and wane at advanced ages (Brown et al. 2012; Haas and Rohlfsen 2010; Shuey and Willson 2008; Willson et al. 2007). Although advantaged groups are likely to have better health than disadvantaged groups over much of the life course, they are disproportionately affected by the deleterious consequences of aging in later life, resulting in narrowing health gaps (House et al. 2005). Therefore, we hypothesize that racial-ethnic, gender, and SES inequalities in health will decrease between middle and late life.

DATA AND METHODS

Data from Waves 1 through 10 of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) were used to test the study hypotheses. The HRS uses a multistage area probability sample, with a target population of all community-dwelling English- or Spanish-speaking adults in the contiguous United States over age 50 (spouses of respondents were interviewed regardless of age eligibility). Blacks and Hispanics were oversampled to allow independent analysis of racial groups. Respondents were interviewed biennially between 1992 and 2010 (response rates were 82% to 89%). The first interviews for the 1931-to-1941, 1942-to-1947, and 1948-to-1953 birth cohorts were in 1992, 1998, and 2004, respectively. A minor proportion of individuals at the target ages of this study were institutionalized, and any respondents who were institutionalized after their baseline interview remained in the study.2 Nonetheless, health disparities may be somewhat understated given the exclusion of institutionalized populations at baseline. Given the relatively small numbers of non-Mexican Hispanics/Latinos in the HRS, and the fact that Hispanic subgroups have different health profiles (Markides et al. 2007), Mexican Americans were the only Hispanics included in this study. In addition, we excluded racial groups other than blacks and whites due to small sample sizes. Thus, the final analytic sample included 12,976 respondents (4,967 white men, 4,832 white women, 997 black men, 1,348 black women, 426 Mexican American men, and 406 Mexican American women).

Dependent Variable

Self-rated health was determined by respondents’ answers to the question, “In general, would you say your health is: excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” at each wave of the survey; responses ranged from 1 (“poor”) to 5 (“excellent”). Self-rated health has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of general health status and to be predictive of morbidity (Ferraro, Farmer, and Wybraniec 1997) and mortality (Idler and Benyamini 1997). It remains a strong predictor of mortality even after accounting for known demographic, social, and medical risk factors, and it is more predictive of mortality than physician assessments (Idler and Benyamini 1997). In addition, studies have found that self-rated health has predictive validity for more objective health measures and mortality across racial-ethnic and gender subgroups (Johnson and Wolinsky, 1994; Kimbro, Gorman, and Schachter 2012).

Independent Variables

Social, Demographic, and Economic Characteristics

Binary variables indexed self-reported race-ethnicity: non-Hispanic black (yes = 1) and Mexican American (yes = 1), with non-Hispanic whites serving as the reference group. Gender was also measured by a binary variable (women = 1, men = 0). Age was measured in years. Socioeconomic measures included years of education and household income (logged sum of all household wages and salaries); income equivalencies across households were created by dividing income by the square root of the number of household members (Brady 2009).3

Control Variables

To account for different rates of dropout and death attrition, a measure of the proportion of waves missing and a binary indicator of whether the respondent died (yes = 1) during the observation were included in the models. Similar approaches have been shown to be an efficient and effective method for minimizing biases associated with sample attrition (Brown et al. 2012). All models included a binary indicator of whether the respondent was born outside of the United States (yes = 1) given the well-documented immigrant health advantage (Markides et al. 2007). In order to account for cohort effects and avoid confounding age-related changes with cohort differences, analyses controlled for birth cohorts (Brown et al. 2012; Yang and Lee 2009). Members of the HRS birth cohort, who serve as the reference group, were born between 1931 and 1941. Other cohorts were born from 1942 to 1947 (war baby cohort) and 1948 to 1953 (early baby boomer cohort). These cohorts correspond to secular changes and shared historical experiences as well as the study cohorts.

Analysis

This study tests the research hypotheses in two steps. First, to examine how race-ethnicity, gender, and SES combine to shape the mean levels of health across ages 51 to 77, we used data from Waves 1 through 10 and multilevel models that were estimated within a mixed-model framework. A hierarchical strategy was used, where repeated observations (Level 1) are nested respondents (Level 2). These models are well suited for panel data because they adjust for non-independence of observations and correlations within clusters (Raudenbush and Byrk 2002). In addition to the fixed effects of covariates, random effects (subject-specific deviations) for the intercept are included in the model. To test the alternative multiple-hierarchy stratification hypotheses, we examined the main effects of, and interactions among, race-ethnicity, gender, and SES on health outcomes. Due to the complexity of interpreting coefficients for interactions among three or more variables, models including Race-ethnicity × SES interactions are stratified by gender, and we use Chow tests to determine whether the coefficients for race-ethnicity and SES (and their interactions) statistically differ for men and women. This approach is commonly used for testing intersectionality hypotheses and provides similar—yet more comprehensible—information than three-way interactions (Landry 2007).

While both multiple jeopardy and intersectionality hypotheses predict that race-ethnicity, gender, and SES affect health, and that women of color with low SES will have the worst health of all race-ethnicity/gender/SES subgroups, they differ in their expectations regarding how these social factors combine to shape health. Evidence that there are nonsignificant interactions among race-ethnicity, gender, and SES—suggesting that the health consequences of racial-ethnic, gender, and SES inequality are independent of each other—would constitute support for the multiple jeopardy hypothesis (Beal 1970; Greenman and Xie 2008). On the other hand, support for the intersectionality hypothesis would be indicated by statistically significant interactions among race-ethnicity, gender, and SES (Brown and Hargrove 2013; Hinze et al. 2012; Umberson et al. 2014). This would suggest that their effects on health are conditional upon each other. For example, findings that racial-ethnic inequality in health is greater among women than among men (as indicated by a Chow test), or that the health benefits of higher SES are weaker (or nonexistent) among people of color (especially women of color) than among whites, would be consistent with the inter-sectionality hypothesis.

The second stage of the analysis extends the first set of analyses by estimating age interactions with race-ethnicity, gender, and SES to determine whether the joint consequences of these social factors are conditional upon age. Random coefficient growth curve models are used to test the aging-as-leveler, persistent inequality, and cumulative disadvantage hypotheses. Growth curve models generated individual trajectories that were based on estimates of person-specific intercepts or initial values (at age 51) and age slopes that described intra-individual patterns of change in health as a function of age between ages 51 and 77. We used linear growth curves with random intercepts and random linear slopes to estimate age trajectories of self-rated health because comparisons of nested likelihood ratio tests of various shapes of health trajectories (e.g., linear, quadratic, or cubic models) suggested that these provided the best fit to the data.4 Regressing coefficients for gender and race-ethnicity, and their interactions, on the age slopes provided information about the pattern of the health inequality over time and formal tests of the life course hypotheses. Findings that age slopes are similar across groups would be consistent with the persistent inequality hypothesis, while findings that health inequalities narrow or widen with age would be consistent with aging-as-leveler or cumulative disadvantage hypothesis, respectively (Haas and Rohlfsen 2010; Willson et al. 2007).

In both stages of analyses, initial models examining additive effects of key covariates were followed by models investigating interactions among these factors. To reduce the likelihood of reverse causality, household income, a time-varying measure, was lagged by one wave. Given subgroup differences in missing waves and mortality rates (see Table 1 for information on group differences in attrition), and the selective nature of attrition, conventional methods that exclude respondents with incomplete data yield biased estimates of inequality in health. To avoid such biases, this study used hierarchical linear models in tandem with maximum likelihood estimation. This approach allowed us to incorporate respondents who have been observed only once, including those who attrited, during the observation period.5 To account for racial-ethnic/gender differences in dropout and death attrition, indicators of proportion of missing interviews and death were included in the models. Item nonresponse was addressed by using listwise deletion, resulting in a loss of 29 respondents. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 and weighted using survey weights provided by the HRS.

Table 1.

Weighted Means/Proportions, by Race-ethnicity and Gender; Health and Retirement Study, Baseline.

| Variable | WM | WW | BM | BW | MM | MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-rated health | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.96* | 3.13*† | 3.04* | 3.28*† |

| (1.16) | (1.15) | (1.22) | (1.14) | (1.22) | (1.14) | |

| 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | |

| Years of education | 13.20 | 12.84*† | 11.43* | 11.85*† | 8.30* | 7.95*† |

| (2.80) | (2.40) | (3.32) | (2.91) | (4.64) | (4.58) | |

| 0–17 | 0–17 | 0–17 | 0–17 | 0–17 | 0–17 | |

| Income (ln) | 10.64 | 10.42*† | 9.91* | 9.51*† | 9.32* | 9.00*† |

| (1.28) | (1.42) | (1.81) | (1.89) | (2.37) | (2.49) | |

| 0–14.22 | 0–14.16 | 0–12.78 | 0–12.83 | 0–13.53 | 0–12.21 | |

| Age | 54.98 | 54.97 | 54.98 | 54.94 | 54.50* | 54.46* |

| (2.99) | (3.04) | (2.92) | (2.99) | (2.85) | (2.79) | |

| 51–61 | 51–61 | 51–61 | 51–61 | 51–61 | 51–61 | |

| Study cohort | ||||||

| HRS | .67 | .73*† | .69 | .70 | .60* | .64 |

| War baby | .15 | .12*† | .12 | .12 | .12 | .09* |

| Early baby boomer | .18 | .15*† | .18 | .18 | .28* | .27* |

| Immigrant | .04 | .04 | .07* | .07* | .46* | .45* |

| Proportion of waves missing | .21 | .17*† | .27* | .22 | .21 | .18 |

| (.290) | (.274) | (.305) | (.289) | (.268) | (.278) | |

| 0–.90 | 0–.90 | 0–.90 | 0–.90 | 0–.90 | 0–.90 | |

| Died | .16 | .12*† | .23* | .20*† | .14 | .09*† |

| N | 4,967 | 4,832 | 997 | 1,348 | 426 | 406 |

Note: WM, WW, BM, BW, HM, and HW refer to white men, white women, black men, black women, Mexican men, and Mexican women, respectively. Standard deviations are reported in parentheses. Ranges for continuous variables are reported below the standard deviations.

p < .05 for comparison of racial-ethnic/gender group to white men,

p < .05 for comparison between the men and women within racial-ethnic groups.

RESULTS

Results in Table 1 show that self-rated health, SES, and control variables differ across racial-ethnic and gender lines. Blacks and Mexican Americans tend to be disadvantaged relative to their white counterparts in terms of health and SES. As expected, results reveal distinct disadvantages for women of color, who have the worst self-rated health and the lowest income levels. Taken together, the patterns of differences in self-rated health and social determinants of health show that those in more privileged positions—namely, whites, men, and white men in particular—tend to be more advantaged in mid- to later life, while black and Mexican American women appear to be the most disadvantaged racial-ethnic/gender groups. These results are largely consistent with well-established inequalities (Brown and Hargrove 2013).

Are the Joint Health Consequences of Racial-ethnic, Gender, and SES Inequality Additive or Multiplicative?

Table 2 presents multilevel models of self-rated health using data from Waves 1 through 10 of the HRS. These models provide statistical tests of our multiple-hierarchy stratification hypotheses regarding racial differences in self-rated health and the (potentially) gendered and classed nature of these differences. All models control for birth cohort, nativity, and dropout and death attrition. Results from Model 1 imply that self-rated health varies along both racial-ethnic and gender lines, as there are statistically significant, negative coefficients for black and Mexican American men and women, as well as the significant Chow tests indicating that women have worse self-rated health than men. Thus, racial-ethnic minorities and women, and especially those who fall in both of those categories, have worse self-rated health than white males. Moreover, the significant Chow tests for the black and Mexican American coefficients suggest that the effects of racial-ethnic and gender inequalities are multiplicative, indicating that the magnitude of the racial-ethnic inequality in self-rated health is greater among women than men, consistent with the intersectionality hypothesis. Results show that all racial-ethnic/gender groups experience poorer self-rated health than white men, and that racial-ethnic minority women have the worst self-rated health. Specifically, white men have the highest self-rated health, followed in descending order by white women, black and Mexican American men, and black and Mexican American women, respectively. Supplemental analyses indicated that there were no statistically significant differences between blacks and Mexican Americans of the same gender (results not shown).

Table 2.

Multilevel Model Estimates of the Effects of Multiple Social Statuses and Interactions on Self-rated Health; Health and Retirement Study, Waves 1-10.

| Fixed effects | Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 3

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | m≠w | Men | Women | m≠w | Men | Women | m≠w | |

| Constant | 3.984*** | 3.887*** | † | 3.857*** | 3.787*** | † | 3.844*** | 3.775*** | † |

| Race (reference white) | |||||||||

| Black | −.393*** | −.543*** | † | −.224*** | −.420*** | † | −.217*** | −.415*** | † |

| Mexican American | −.543*** | −.769*** | † | −.105* | −.267*** | † | −.177** | −.343*** | † |

| SES | |||||||||

| Education | .091*** | .105*** | † | .103*** | .117*** | † | |||

| Income | .026*** | .030*** | .023*** | .037*** | |||||

| Race × SES | |||||||||

| Black × Education | −.033*** | −.029*** | |||||||

| Mexican American × Education | −.037*** | −.033** | |||||||

| Black × Income | .020 | −.018* | † | ||||||

| Mexican American × Income | −.007 | −.027** | |||||||

| Age | −.035*** | .030*** | † | −.035*** | .030*** | † | −.035*** | .030*** | † |

| Cohort (reference HRS) | |||||||||

| War baby | −.134*** | −.133*** | −.211*** | −.237*** | −.212*** | −.241*** | |||

| Early baby boomer | −.295*** | −.214*** | −.402*** | −.351*** | −.402*** | −.355*** | |||

| Foreign-born | −.004 | −.099* | .101* | .053 | .067 | .021 | |||

| Proportion of waves missing | −.306*** | −.144** | † | −.258*** | −.105* | † | −.251*** | −.099* | † |

| Death | −.744*** | −.825*** | −.678*** | −.718*** | −.677*** | −.718*** | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Random effects | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Level 1 residual | .645*** | .535*** | .645*** | .534*** | .645*** | .534*** | |||

| Level 2 intercept | .679*** | .699*** | .592*** | .608*** | .590*** | .606*** | |||

|

| |||||||||

| −2 log likelihood | 104654 | 113086 | 103805 | 112102 | 103779 | 112071 | |||

Note: “m≠w” indicates Chow tests for differences between men and women; SES = socioeconomic status; HRS = Health and Retirement Study.

Indicates a statistically significant (p < .05) difference in coefficients for men and women.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Model 2 of Table 2 adds SES measures. Results in Model 2 show that both education and income are positively associated with self-rated health. Moreover, adjusting for these SES indicators reduces the magnitude of racial-ethnic inequality in self-rated health, though they remain significant.

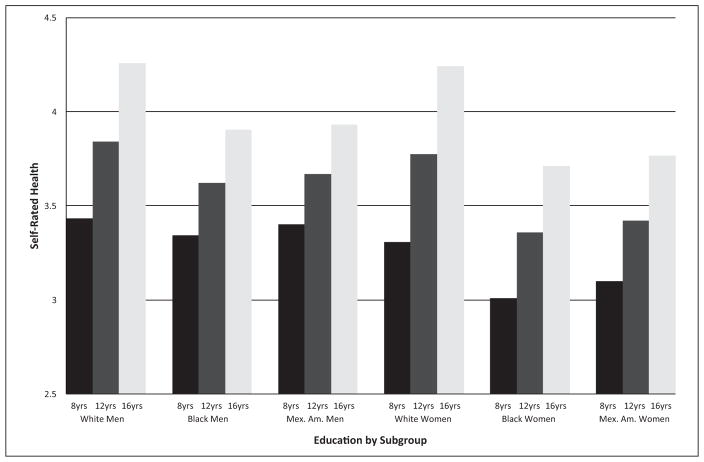

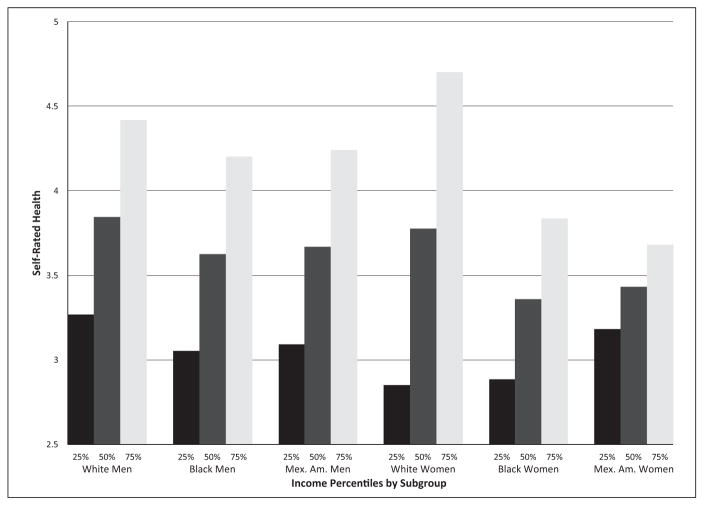

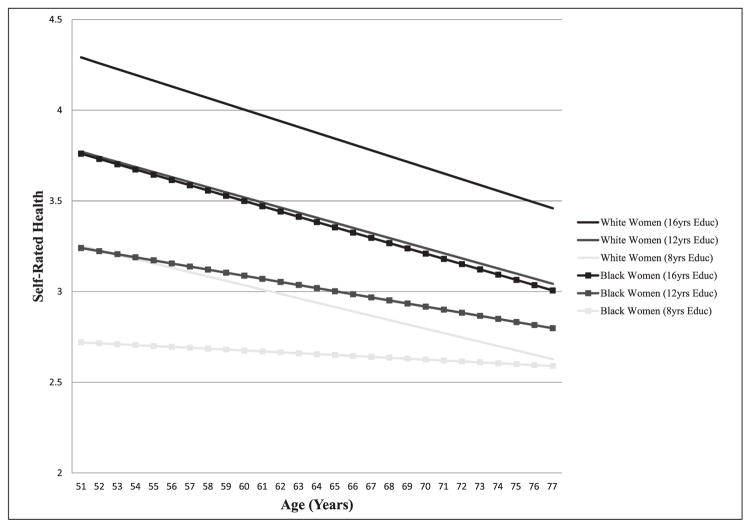

Model 3 of Table 2 tests for interactions among race-ethnicity, gender, and SES. Statistically significant, positive coefficients for education in tandem with significant negative coefficients for interactions between black/Mexican American and education suggest that the education–health gradient is less steep for blacks and Mexican Americans than whites (intersectionality hypothesis); this is the case for both men and women. The association between income and self-rated health is similar across race-ethnicity among men. However, findings indicate that higher levels of income are less beneficial in terms of health for black and Mexican American women than white women. Furthermore, the statistically significant Chow test for gender differences in the Black × Income coefficient indicates that there is a three-way interaction among race-ethnicity, gender, and SES—providing further evidence to support the intersectionality hypothesis. These findings are presented in Figures 1 and 2, which provide graphical illustrations of the joint consequences of race-ethnicity, gender, and SES on self-rated health (based on estimates from Model 3 of Table 2). Results suggest that white men with high levels of education have the best health and that black and Mexican American women with low levels of education have the worst health, with other race-ethnicity/gender/education groups occupying liminal statuses. Also apparent is the fact that racial-ethnic gaps in health are larger at higher levels of education than at lower levels of education for both men and women. Similarly, among women, racial-ethnic inequality in health is greater at higher levels of income than at lower levels of income. Interestingly, Mexican American women with low incomes have better health than their white counterparts, which may be due to the buffering effects of sociocultural factors.

Figure 1.

Self-rated Health by Race-ethnicity, Gender, and Education; Health and Retirement Study, Waves 1-10.

Figure 2.

Self-rated Health by Race-ethnicity, Gender, and Income Level; Health and Retirement Study, Waves 1-10.

Results indicate that sociodemographic control variables are predictive of self-rated health. Specifically, compared to the HRS cohort, the war baby and early baby boomer cohorts report worse health, as do respondents with higher proportions of missing waves and those who died compared to respondents who did not. The effects of these sociodemographic control variables are generally similar across gender, though the magnitude of the effect of proportion of waves missing is greater among men than among women.

Does Inequality in Health Decrease, Remain Stable, or Increase Between Middle and Late Life?

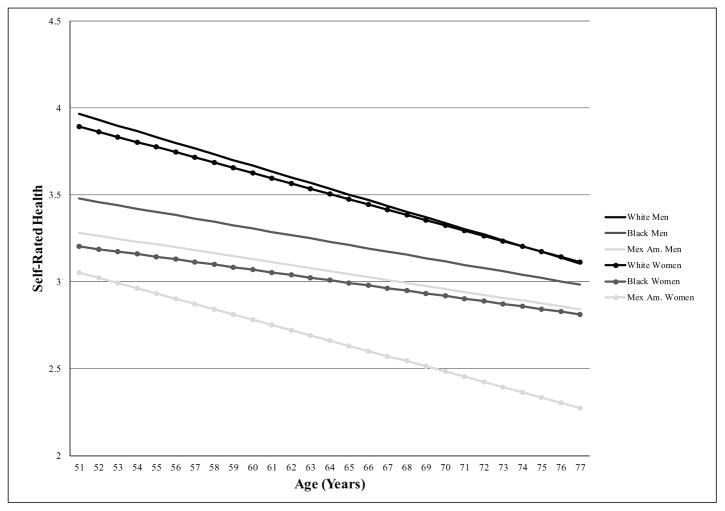

Table 3 presents growth curve models of self-rated health between ages 51 and 77. These models provide statistical tests of our life course hypotheses (aging as leveler, persistent inequality, and cumulative disadvantage) regarding racial-ethnic differences in self-rated health intercepts (levels at age 51) and slopes (rates of change with age) and the potentially gendered and classed nature of these differences. Each of these models controls for birth cohort, nativity, and dropout and death attrition. Model 1 of Table 3 tests for racial-ethnic and gender inequality in self-rated health trajectories. As predicted by the aging-as-leveler hypothesis, the statistically significant negative coefficients for self-rated health intercepts among black men and women (−.487 and −.691, respectively) in tandem with the significant positive black coefficients for self-rated health age-slopes among men and women (.014 and .015, respectively) indicate that health gaps between black men and women and their same-gender white counterparts decrease between ages 51 and 77 by 72% (from .487 to .135) and 56% (from .691 to .301), respectively. Similarly, the statistically significant coefficients for Mexican American men’s self-rated health intercepts (−.682) and slopes (.016) reveal that Mexican American–white health inequality among men declines between ages 51 and 77 by 60% (from .682 to .275)—consistent with the aging-as-leveler hypothesis. Overall, results from Model 1 show that black men and women and Mexican American men experience declines in self-rated health with age at approximately half the rate of their white counterparts. Mexican American women, on the other hand, experience persistent inequality in self-rated health relative to white women. These findings (based on Model 1 of Table 3) are illustrated in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Growth Curve Model Estimates of the Effects of Multiple Social Statuses and Interactions on Self-rated Health Trajectories (Intercept and Age Slope); Health and Retirement Study, Waves 1-10.

| Fixed effects | Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 3

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | a m≠w | Men | Women | m≠w | Men | Women | m≠w | |

| Intercept | 3.965*** | 3.895*** | † | 3.810*** | 3.778*** | 3.800*** | 3.771*** | ||

| Race (reference white) | |||||||||

| Black | −.487*** | −.691*** | † | −.287*** | −.543*** | † | −.271*** | −.531*** | † |

| Mexican American | −.682*** | −.842*** | −.179* | −.257*** | −.279*** | −.351*** | |||

| SES | |||||||||

| Education | .102*** | .122*** | † | .112*** | .130*** | ||||

| Income | .056*** | .044*** | .051*** | .048*** | |||||

| Race × SES | |||||||||

| Black × Education | −.011 | −.005 | |||||||

| Mexican American × Education | −.049** | −.032* | |||||||

| Black × Income | .027 | .002 | |||||||

| Mexican American × Income | −.004 | −.035 | |||||||

| Cohort (reference HRS) | |||||||||

| War baby | −.137*** | −.178*** | −.223*** | −.298*** | −.224*** | −.299*** | |||

| Early baby boomer | −.263*** | −.272*** | −.384*** | −.428*** | −.385*** | −.433*** | |||

| Foreign-born | .094 | −.087 | .217*** | .089 | .165** | .054 | |||

| Proportion of waves missing | −.286*** | −.027 | † | −.239*** | .008 | † | −.236*** | .012 | † |

| Death | −.512*** | −.580*** | −.436*** | −.464*** | −.434*** | −.463*** | |||

| Linear slope (age) | −.033*** | −.030*** | −.030*** | −.028*** | −.030*** | −.028*** | |||

| Race (reference white) | |||||||||

| Black | .014** | .015*** | .007* | .012*** | .005 | .011*** | |||

| Mexican American | .016** | .008 | .009 | −.002 | .012 | .001 | |||

| SES | |||||||||

| Education | −.001* | −.002*** | −.001 | −.001** | |||||

| Income | −.004*** | −.002** | −.003** | −.002* | |||||

| Race × SES | |||||||||

| Black × Education | −.002* | −.002* | |||||||

| Mexican American × Education | .001 | −.001 | |||||||

| Black × Income | −.001 | −.001 | |||||||

| Mexican American × Income | −.001 | .002 | |||||||

| Cohort (reference HRS) | |||||||||

| War baby | −.001 | .005 | .001 | .007* | .001 | .006* | |||

| Early baby boomer | −.005 | .014* | † | −.003 | .015* | † | −.003 | .015* | † |

| Foreign-born | −.010* | −.001 | −.011* | −.003 | −.010* | −.002 | |||

| Proportion of waves missing | −.008 | −.023** | −.007 | −.022** | −.007 | −.021** | |||

| Death | −.024*** | −.024*** | −.025*** | −.025*** | −.026*** | −.025*** | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Random effects | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Level 1 residual | .589*** | .480*** | .590*** | .480*** | .590*** | .480*** | |||

| Level 2 age | .001*** | .001*** | .001*** | .001*** | .001*** | .001*** | |||

| Level 2 intercept | .672*** | .714*** | .576*** | .613*** | .573*** | .610*** | |||

|

| |||||||||

| −2 log likelihood | 103939 | 1119077 | 103016 | 110894 | 102983 | 110860 | |||

Note: SES = socioeconomic status; HRS = Health and Retirement Study.

m≠w indicates Chow tests for differences between men and women.

Indicates a statistically significant (p < .05) difference in coefficients for men and women.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Figure 3.

Age Trajectories of Self-rated Health by Race-ethnicity and Gender; Health and Retirement Study, Waves 1-10.

Model 2 of Table 3 adds SES measures. For both men and women, education and income are positively associated with self-rated health intercepts but negatively associated with self-rated health slopes. This suggests that, compared to individuals with lower levels of education and income, those with higher levels of education and income have better self-rated health at age 51 but steeper health declines between ages 51 and 77, providing further evidence to support the aging-as-leveler hypothesis. It is also important to note that adjusting for SES measures reduced the magnitude of racial-ethnic inequality in health intercepts, though they remain statistically significant. Overall, results from Chow tests in Model 1 indicate that there are gender differences in the influences of race and education on self-rated health intercepts but that racial-ethnic and SES inequalities in self-rated health age slopes are not gendered.

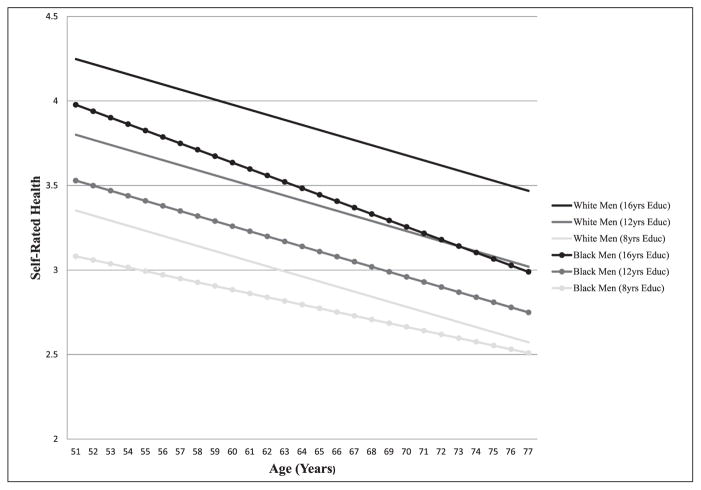

Model 3 of Table 3 adds tests for interactions between race-ethnicity, gender, and SES on self-rated health trajectories. The statistically significant negative slope coefficient for the Black × Education term (−.002) among men suggests that black men with higher levels of education experience more rapid declines in self-rated health with age compared to white men with similar levels of education as well as compared to black men with lower levels of education. Thus, the self-rated health gap between black and white men with higher levels of education increases with age, consistent with the cumulative disadvantage hypothesis; conversely, the magnitude of the self-rated health disparity between black men with higher levels of education versus those with lower levels of education declines with age, as predicted by the aging-as-leveler hypothesis. Similarly, the significant negative slope coefficient for the Black × Education term among women (−.002) suggests that black women with higher levels of education also experience particularly steep self-rated health declines with age. In fact, between ages 51 and 77, black women with 16 years of education experience self-rated health declines that are 438% steeper than black women with eight years of education (.700 vs. .130). Figures 4 and 5 present graphical illustrations of the estimates from Model 3 of Table 3 for men and women, respectively. For the sake of concision, Mexican Americans are not included in Figures 4 and 5; results showed that there are no significant Mexican American × Education interactions on the slopes of self-rated health. There is also no evidence of significant interactions between race-ethnicity and income on age slopes of self-rated health among either men or women.

Figure 4.

Age Trajectories of Self-rated Health by Race-ethnicity and Education among Men; Health and Retirement Study, Waves 1-10.

Note: For the sake of concision, Mexican American men are not included in Figure 4; results showed that their age slopes by education level did not differ from those of white men.

Figure 5.

Age Trajectories of Self-rated Health by Race-ethnicity and Education among Women; Health and Retirement Study, Waves 1-10.

Note: For the sake of concision, Mexican American women are not included in Figure 5; results showed that their age slopes by education level did not differ from those of white women.

Several of the sociodemographic control variables affect trajectories of self-rated health. Results generally indicate that later birth cohorts, higher proportions of missing waves, and death were predictive of worse self-rated health intercepts; and being foreign-born, higher proportions of missing waves, and death are also predictive of more rapid declines in self-rated health with advancing age (though the effects of these factors varied somewhat by gender). Importantly, our substantive findings on racial-ethnic, gender, and SES differences in self-rated health trajectories are similar regardless of whether cohort and attrition measures are included in the models, suggesting that our results are robust to different cohort and attrition specifications.

DISCUSSION

Although the social stratification of health along racial-ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic lines is well established in the literature, fewer quantitative studies have examined how racial-ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic inequality combine to affect health. Rather, studies have tended to examine their separate influences or assume that that their health consequences are additive. Moreover, the few studies that have examined the joint health effects of multiple social statuses have not incorporated life course perspectives and methods, leaving unanswered the question of how the simultaneous and intersecting consequences of race-ethnicity, gender, SES, and age influence health inequality. Given current and projected demographic trends related to the aging and diversification of the U.S. population, this unanswered question represents a critical gap in the extant literature on the social stratification of health. Our study addresses this gap and extends previous work in several important ways.

First, aside from a few recent studies, this study is among the first quantitative studies to employ a multiple-hierarchy stratification approach to conceptualizing and measuring racial-ethnic and gender inequality in health. For example, we extended previous research that compared the health of various racial-ethnic/gender subgroups to others (e.g., Geronimus et al. 2007; Read and Gorman 2006; Warner and Brown 2011) by explicitly testing alternative multiple-hierarchy stratification hypotheses regarding whether social statuses combined in an additive (multiple jeopardy) or multiplicative (intersectionality) fashion. Our findings revealed that racial-ethnic inequality in self-rated health is gendered: racial-ethnic inequality was greater among women than among men, and the female health disadvantage tended to be greater among blacks and Mexican Americans than among whites. Black and Mexican American women had the worst self-rated health, while white men had the best. Importantly, results strongly supported the intersectionality hypothesis, as indicated by the interactive relationships between race-ethnicity and gender. Specifically, we found that being black or Mexican American and female has deleterious health consequences beyond those already accounted for by race-ethnicity or gender alone.

Second, this study extends extant research by investigating how SES intersects with race-ethnicity and gender to affect the social distribution of self-rated health. Few studies have examined how SES interacts with race-ethnicity and gender to shape health (e.g., Cummings and Jackson 2008; Hayward et al. 2000; Hinze et al. 2012). Of these, only two focused on the social distribution of self-rated health (e.g., Cummings and Jackson 2008; Hinze et al. 2012). Results from our study indicated that there are consistent interactions between SES and race-ethnicity and, to a lesser extent, among SES, race-ethnicity, and gender. Specifically, findings showed that while education is positively associated with self-rated health, the education–health gradient is steeper for white men and women than for their black and Mexican American counterparts. While there were no racial-ethnic differences in the income–health relationship among men, the income–health gradient was steeper for white women than for black and Mexican American women. Moreover, there was a statistically significant three-way interaction among race-ethnicity, gender, and income, indicating that black women receive diminished self-rated health returns to income, compared to white women and men as well as black men. Socioeconomic resources do not appear to confer self-rated health advantages equally across racial-ethnic and gender groups. Within the context of unequal opportunities, attempts by marginalized groups to acquire traditional socioeconomic resources in the face of blocked opportunities may produce negative health consequences (Jackson and Williams 2006; Pearson 2008). Taken together, these results reveal that racial-ethnic, gender, and SES stratification combine in mostly multiplicative ways, consistent with the intersectionality hypothesis. Importantly, these interconnections would not have been evident if we had employed a more conventional approach, such as examining the health consequences of race-ethnicity, gender, and SES separately or assuming that their effects were additive. This suggests that interactive, multiple-hierarchy stratification approaches have considerable utility for uncovering a more nuanced and complex understanding of between- and within-group health inequalities than unidimensional and additive approaches.

A third key contribution of this study is that we integrated life course perspectives with a multiple-hierarchy stratification approach in order to understand intracohort inequality dynamics. Specifically, we extended previous studies (e.g., Brown and Hargrove 2013; Hinze et al. 2012) by examining whether the simultaneous and overlapping effects of age, race-ethnicity, gender, and SES result in narrowing, persistent, or widening self-rated health gaps between middle and later life. Scholarship on the social stratification of aging and health illustrates that the health consequences of social positions are likely to vary with age (House et al. 2005; Willson et al. 2007). The relative inattention to how age intersects with race-ethnicity, gender, and SES to shape health trajectories, and the related overreliance on cross-sectional data, in research on the social stratification of health reflects an implicit assumption that health inequality is stable across the life course. While a handful of studies have examined differences in age trajectories of health along a single social status, such as race-ethnicity (Haas and Rohlfsen 2010; Kim and Miech 2009), gender (Anderson et al. 1998; Liang et al. 2008), or SES (Lantz et al. 2001; Ross and Wu 1996), we are not aware of any other studies that have tested how age simultaneously interacts with all three social statuses to shape health.

Findings from our initial growth curve models, which examined age differences along various social dimensions separately and in an additive fashion, suggested that there was strong support for the aging-as-leveler hypothesis. For example, racial-ethnic gaps in self-rated health largely appeared to decline between middle and late life, consistent with previous studies (Brown et al. 2012). Furthermore, the health advantages associated with higher levels of education and income appeared to erode as individuals aged, similar to findings from previous research (House et al. 2005; Willson et al. 2007). However, our subsequent growth curve models, which examined the simultaneous intersections of age, race-ethnicity, gender, and SES, provided evidence of three-way interactions between age, race-ethnicity, and SES. These results, therefore, revealed more nuanced and heterogeneous social patterning of health trajectories than was evident from the simpler models. Specifically, black men and women with higher levels of education exhibit more rapid health declines with age compared to white men and women with comparable levels of education. Consequently, the self-rated health gap between highly educated blacks and whites increases with age, as predicted by the cumulative disadvantage hypothesis. Moreover, compared to whites, blacks experience more rapid erosion of the health benefits of higher levels of education with age. This is consistent with emerging evidence suggesting that blacks experience diminished health returns to SES relative to whites, which may be due to the stress of achieving higher SES in the face of opportunities that have been blocked by institutional racism and in the midst of increased encounters of interpersonal racism (Colen 2011; Farmer and Ferraro 2005; Jackson and Williams 2006; Pearson 2008). Others have also noted racial-ethnic differences in the economic returns on education (Oliver and Shapiro 2006) as well as the presence of residential segregation even at higher levels of SES (Pattillo 2005), both of which could contribute to vast differences across racial-ethnic groups in living conditions that matter for health among the highly educated.

Importantly, our findings of three-way interactions between age, race-ethnicity, and SES were not evident in our initial, simpler models. These results, which are net of differential prospective attrition, underscore the fact that age is an additional dimension of inequality that simultaneously intersects with other dimensions. In light of our findings that the extent of racial-ethnic, gender, and SES stratification in health varies with age, it is clear that the common implicit assumption that health disparities are stable across the life course obscures the dynamic and layered nature of health disparities between middle and late life. Our results suggest that life course approaches that contextualize health experiences along racial-ethnic, gender, and SES lines have considerable utility for understanding the social stratification of health trajectories.

While we used existing racial-ethnic and gender categories to understand patterns of health inequality, we recognize that these categories are socially constructed and historically contingent. Moreover, consistent with critical race and feminist perspectives, we interpret racial-ethnic and gender inequalities not as effects of race-ethnicity and gender per se but, rather, as a result of relations of domination and subordination stemming from racism, sexism, and their consequences for class inequality (McCall 2005; Weber 2010; Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva 2008). For example, racial residential segregation, a manifestation of institutional racism that remains stubbornly high, leads to differential exposure to neighborhood risks and resources that affect health (Williams and Collins 2001). Indeed, some studies have found that accounting for racial-ethnic differences in neighborhood conditions reduces the minority health disadvantage (LaVeist, Pollack, et al. 2011). In addition, there is accumulating evidence that racial-ethnic health inequality stems, in part, from unequal exposure to chronic and discrimination stressors (Bratter and Gorman 2011; Goosby and Heidbrink 2013; Thoits 2010; Williams and Mohammed 2009). The effects may be particularly harmful for nonwhite women, who may experience especially high levels of discrimination stress given that they are exposed to chronic stress-ors associated with sexism and racism (Grollman 2014), which simultaneously contribute to their lower class status (Davis 1981), as well as gendered racial discrimination, which is simultaneously based on both their race-ethnicity and gender (Harnois and Ifatunji 2011). The data used for this study do not include information on the neighborhood conditions of the respondents or various types of discrimination they may have faced. However, future research should examine the roles of these factors in order to better understand the mechanisms through which racial-ethnic inequality in health becomes gendered.

Although this study highlights the unique disadvantages that racial-ethnic minority women endure, racial-ethnic minority men also experience distinct racialized limits on their life chances—for example, disproportionately high rates of unemployment, incarceration, victimization due to violent crimes, and mortality (Griffith, Ellis, and Allen 2013; Pettit 2012; Williams 2003). Thus, it is not fruitful to view the examination of gendered racial inequality as a within-race competition of which gender is the most disadvantaged. Rather, consistent with the life course principle of linked lives (Elder, Johnson and Crosnoe 2003), we acknowledge that the distinct disadvantages experienced by racial-ethnic minority men and women have reciprocal effects within families and communities. In our patriarchal society, women are more likely to be family caretakers and, thus, are especially likely to experience vicarious distress and vicarious racism (Nuru-Jeter et al. 2008) when family members experience stressful events and health problems (Turner and Avison 2003). Consequently, in addition to the gendered and racialized burdens that racial-ethnic minority women experience, the ways in which society marginalizes and situates men of color—who are their family members, partners, and friends—likely affects and limits the life chances of women of color, through decreased socioeconomic resources, compromised family functioning, and increased levels of stress and isolation (Lee and Wildeman 2013). Therefore, future research should examine the relative contributions of disadvantages and stressors experienced by black and Mexican American women as well as their significant others to their especially poor health.

This study has several limitations worth noting. First, small sample sizes in the HRS preclude inclusion of Asians, Native Americans, and Hispanics other than those of Mexican descent in health disparities research. Furthermore, although blacks and Hispanics were oversampled, there are relatively modest sample sizes of blacks and Hispanics with high SES in the HRS, which may limit the statistical power necessary to detect racial-ethnic differences in the effects of high SES on health. Additional data collection efforts are needed to investigate gender and SES heterogeneity with respect to health among racial-ethnic minorities. A second limitation of this study is our inability to examine the intersections of a wider array of social factors. Multiple-hierarchy stratification and intersectionality perspectives in particular emphasize the salience of multiple identities and social statues (beyond just race-ethnicity, gender, SES, and age), including nativity, sexual orientation, disability, and religion (Schulz and Mullings 2006). Though it is beyond the scope of this study, future research should examine how a wider array of social factors simultaneously and interactively affect health trajectories. While there are a number of analytic challenges to accomplishing this goal solely through quantitative research, qualitative approaches are particularly well suited for providing rich theoretical insights and giving voice to multiply disadvantaged groups (McCall 2005).

Third, although the analyses account for right-censoring by controlling for prospective death and dropout attrition, results presented here may be biased given well-documented gender and racial-ethnic differences in mortality rates prior to midlife. Specifically, excess mortality among men and racial-ethnic minorities, relative to women and whites, may lead to overestimates of gender disparities and conservative estimates of racial-ethnic inequality in health (Hayward et al. 2000). Accordingly, findings should be interpreted as conditional on survival to midlife. Fourth, the health measure used in this study—self-rated health—is subjective, and when respondents rate their own health, it is unclear to whom they are comparing themselves. Nonetheless, previous research has validated self-rated health as a useful measure of general health and a predictor of more objective indicators of health, such as clinical assessments, doctor-diagnosed health conditions, and mortality (Ferraro et al. 1997; Idler and Benyamini 1997) across racial-ethnic, gender, and age groups (Johnson and Wolinsky 1994; Kimbro et al. 2012). Future research is needed to determine whether and how race-ethnicity, gender, SES, and age intersect to affect other measures of morbidity.

Despite these limitations, we find strong support for our hypothesis that racial-ethnic health inequality varies by gender and SES. These findings are significant because they highlight the fact that health is shaped by multiple dimensions of inequality simultaneously and interactively. Moreover, by focusing on heterogeneity within racial-ethnic groups, our findings render visible the experiences of women of color with low SES, who are especially vulnerable in terms of health due to their disadvantaged positions within racial-ethnic, gender, and SES hierarchies. The health disparities highlighted in this study, therefore, reflect an excess and unequal distribution of human suffering that requires more than the typical single-issue policy responses. Policies that address the multiple pathways to health inequality, while considering the differential effects of those policies on racial-ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic inequality more broadly, are needed.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (RCMAR Grant P30AG043073) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant No. 64300 and Subaward No. 100927DLH216-02). are MAR, because all of the data are used in the analysis and a fully efficient estimation procedure (maximum likelihood) is utilized, estimates from the growth curve models are asymptotically unbiased (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002).

Biographies

Tyson H. Brown is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at Duke University. His research focuses on understanding how and why race-ethnicity and other social factors, such as gender, class, immigration, and age, intersect to shape health across the life course. He is also interested in identifying the structural and psychosocial mechanisms underlying between- and within-group health inequalities.

Liana J. Richardson is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is also a fellow at the Carolina Population Center. Her research focuses on the link between social inequalities and health, with particular interest in examining health disparities as both causes and consequences of social inequalities within and across generations.

Taylor W. Hargrove is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Sociology and Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Broadly, her research interests include social stratification, race-ethnicity, medical sociology, and aging and the life course. She is currently engaged in research that investigates the ways in which race, gender, and social class combine to influence health disparities. She is also interested in examining factors that lead to within-group heterogeneity in health among black Americans, such as stress, discrimination, and skin tone.

Courtney S. Thomas is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California at Los Angeles and an assistant professor of sociology and African American and Africana studies at the University of Kentucky. Her research focuses on the social and psychological factors that contribute to health inequality at the intersections of race, gender, and class. She is particularly interested in identifying the mechanisms underlying health paradoxes such as poor outcomes among middle-class blacks.

Footnotes

We refer to blacks and Mexican Americans collectively when asserting that these racial and ethnic minorities may exhibit similar health consequences of social factors, such as racism. However, we recognize that blacks and Mexican Americans have faced distinct sociohistorical events and processes that have differentially shaped life chances among, social standing of, and society’s relations to each group. Our use of a collective term to refer to these groups, therefore, should not be interpreted as suggesting that blacks and Mexican Americans have equivalent lived experiences and reactions to such experiences. Instead, we are merely acknowledging the possibility of shared social experiences across these groups (as a result of their positioning within the racial and socioeconomic hierarchies) that can produce parallel health outcomes among them.

Despite disproportionately high rates of incarceration among racial- and ethnic-minority men (Pettit 2012), less than 1% of black and Hispanic men age 55 or older in 2000 were incarcerated (Beck and Karberg 2001), suggesting that differential rates of incarceration are unlikely to significantly bias estimates of racial-ethnic and gender inequality in health among middle-aged and older adults.

The distributions of both education and income differ by race-ethnicity, with relatively smaller proportions of blacks and Hispanics having high levels of socioeconomic status compared to whites. However, sensitivity analyses that used windsorized measures of education and income yielded substantively similar results to those presented in this study, suggesting that our findings are robust to different education and income distributions.

Consistent with previous studies on health trajectories that have used growth curve models that assume a Gaussian distribution (Kim and Miech 2009; Yang and Lee 2009), this study uses the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS 9.3 to specify a multilevel model. Although the outcome variable does not conform to the Gaussian distribution, ancillary analysis using the Shapiro-Francia test of normality indicates that the residuals are distributed normally and thus the normality assumption is not violated. Moreover, supplemental mixed models using log- and square root–transformed health outcomes, as well as ordinal fixed-effects models, produced comparable results to those assuming a normal distribution, suggesting that the results are robust to alternative assumptions regarding the distribution (see Warner and Brown 2011). Therefore, the final models presented here were estimated using the computationally efficient PROC MIXED procedure.

Under these circumstances, Raudenbush and Bryk (2002) note that (1) the data may be assumed to be missing at random (MAR), meaning that the probability of missing a time point is independent of missing data given the observed data, and (2) this is a reasonable assumption when the observed data include variables related to both missingness and the dependent variable. Assuming the data

References

- Ailshire Jennifer A, House James S. The Unequal Burden of Weight Gain: An Intersectional Approach to Understanding Social Disparities in BMI Trajectories from 1986 to 2001/2002. Social Forces. 2011;90(2):397–423. doi: 10.1093/sf/sor001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon S. Overlapping Disadvantages and the Racial/Ethnic Graduation Gap among Students Attending Selective Institutions. Social Science Research. 2007;36(4):1475–99. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Roger T, James Margaret K, Miller Michael E, Worley Angela S, Longino Charles F., Jr The Timing of Change: Patterns in Transitions in Functional Status among Elderly Persons. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1998;53B(1):S17–S27. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.1.s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck Allen J, Karberg Jennifer C. Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2001. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. NCJ 185989. [Google Scholar]

- Beal Frances M. Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female. Detroit, MI: Radical Education Project; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Bird Chloe, Rieker Patricia. Gender and Health: The Effects of Constrained Choices and Social Policies. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brady David. Rich Democracies, Poor People: How Politics Explain Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bratter Jenifer, Gorman Bridget. Is Discrimination an Equal Opportunity Risk? Racial Experiences, Socioeconomic Status and Health Status among Black and White Adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52(3):365–82. doi: 10.1177/0022146511405336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman Paula A, Cubbin Catherine, Egerter Susan, Chideya Sekai, Marchi Kristen S, Metzler Marilyn, Posner Samuel. Socioeconomic Status in Health Research: One Size Does Not Fit All. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(22):2879–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Tyson H, Hargrove Taylor W. Multidimensional Approaches to Examining Gender and Racial/Ethnic Stratification in Health. Women, Gender, and Families of Color. 2013;1(2):180–206. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Tyson H, O’Rand Angela, Adkins Daniel E. Race/Ethnicity and Health Trajectories: Tests of Three Hypotheses across Multiple Groups and Health Outcomes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2012;53(3):359–77. doi: 10.1177/0022146512455333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo Hae Yeon, Ferree Myra Marx. Practicing Intersectionality in Sociological Research: A Critical Analysis of Inclusions, Interactions and Institutions in the Study of Inequalities. Sociological Theory. 2010;28(2):147–67. [Google Scholar]

- Clark Daniel O, Maddox George L. Racial and Social Correlates of Age-related Changes in Functioning. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1992;47(5):S222–S232. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.5.s222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colen Cynthia G. Addressing Racial Disparities in Health Using Life Course Perspectives: Toward a Constructive Criticism. Du Bois Review. 2011;8(1):79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Collins Patricia H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay Will H. Constructions of Masculinity and Their Influence on Men’s Well Being: A Theory of Gender and Health. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50(10):1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings Jason L, Jackson Pamela Braboy. Race, Gender, and SES Disparities in Self-assessed Health, 1974–2004. Research on Aging. 2008;30(2):137–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer Dale. Cumulative Advantage/Disadvantage and the Life Course: Cross Fertilizing Age and Social Science Theory. Journals of Gerontology. Series B. 2003;58(6):S327–S337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.s327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis Angela. Women, Race, and Class. New York: Random House; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dill Bonnie T, Zambrana Ruth E. Critical Thinking about Inequality: An Emerging Lens. In: Dill BT, Zambrana RE, editors. Emerging Intersections: Race, Class, and Gender in Theory, Policy, and Practice. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2009. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois WEB. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; 1899. [Google Scholar]