Abstract

Using longitudinal data from early adolescence through young adulthood, this study examined the association between different types of postsecondary education (PSE), age of enrollment in PSE, and the trajectory of alcohol use for Canadian young adults (N = 521). Trajectories of alcohol use were compared across young adults at 2-year colleges, 4-year universities, transfer programs (started at a 2-year college and transferred to a 4-year university), and terminal high school graduates. While initial findings revealed significant differences in the drinking trajectories of 2-year college students and 4-year university students, all differences were accounted for by variability in the age of enrollment. Overall, there were few differences in heavy drinking across types of institutions, but younger students increased their alcohol use more than older students following enrollment. However, young adults who do not attend PSE may be at greatest risk for heavy drinking over time.

Keywords: alcohol use, emerging adulthood, postsecondary education, college, growth curve modeling

At the population level, alcohol use typically accelerates during the transition to adulthood, peaks around age 21, and then gradually declines (Maggs & Schulenberg, 2005; Thompson, Stock-well, Leadbeater, & Homel, 2014). Some research suggests that young adults who attend postsecondary education (PSE), particularly 4-year colleges, have steeper increases in alcohol use than young adults who do not attend PSE (Carter, Brandon, & Goldman, 2010; Dowdall & Wechsler, 2002; Jackson, Sher, & Park, 2005). However, it is unclear whether increases in alcohol use also occur for young adults who attend other types of PSE or whether increases in alcohol use are influenced by how old young adults are when they enroll. Moreover, research to date has almost exclusively been conducted with U.S. samples of young adults, limiting the generalizability of findings to countries with different education systems and alcohol regulations (i.e., legal drinking age). Using longitudinal data on Canadian youth from early adolescence to the mid-20s, this study investigated whether the trajectory of alcohol use varied as a function of type of PSE and age at the time of postsecondary enrollment. This is the first Canadian study to examine the longitudinal association between PSE and alcohol use.

The high levels of alcohol use and experiences of alcohol-related harms experienced by postsecondary students internationally are well recognized (Dantzer, Wardle, Fuller, Pampalone, & Steptoe, 2006; Gliksman, Adlaf, Demers, & Newton-Taylor, 2003; Jackson et al., 2005; Karam, Kypri, & Salamoun, 2007). However, the evidence documenting differences in levels of alcohol use between postsecondary students and same-aged peers who do not attend PSE is inconsistent. A review by Carter, Brandon, and Goldman (2010) summarized the findings from all 18 U.S. studies comparing drinking between PSE students and their age-matched peers. Across studies the level of alcohol use among PSE students has been found to be greater than (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002; Slutske et al., 2004), equal to (Chen, Dufour, & Yi, 2004; Gfroerer, Greenblatt, & Wright, 1997; Reifman, Ro, Barnes, & Feng, 2010; White et al., 2006), and less than (Lanza & Collins, 2006; Muthén & Muthén, 2000) nonattending peers. To our knowledge, only one study has been conducted outside the United States. This New Zealand study found that the prevalence of heavy drinking was significantly higher among university students compared to the same age-group in the general population (Kypri et al., 2009).

These mixed findings may reflect the considerable variability within this age-group not yet accounted for in previous studies including the following: (1) heterogeneity in the types of PSE pursued and (2) variability in the age of enrollment in PSE. Identifying how this diversity relates to trajectories of alcohol use will add clarity to the alcohol education literature and help identify whether prevention and intervention efforts need to be tailored to specific types of institutional settings that vary in drinking cultures and student body composition.

Heterogeneity in Educational Pathways

Failure to differentiate among types of PSE has been identified as a specific shortcoming of the alcohol education literature (Carter et al., 2010; Fleming, White, Haggerty, Abbott, & Catalano, 2012). Nearly 50% of Canadian postsecondary students (aged 18–26; Shaienks & Gluszynski, 2007) and 71% of U.S. students (aged 18–24; U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, 2012) attend a 4-year university. Thirty-three percent of Canadian students and 29% of U.S. student attend a 2-year community college. Approximately 8–10% of Canadian and U.S. students are transfer students who start at a 2-year community college and then transfer to a 4-year university (Association of Canadian Community Colleges, 2011; Cowin, 2013; Fleming et al., 2012; Provasnik & Planty, 2008; Shaienks, Gluszynski, & Bayard, 2008). However, few North American longitudinal studies have distinguished between different types of postsecondary pathways when examining changes in alcohol use (Carter et al., 2010).

Why might heavy drinking differ between young adults who pursue different educational pathways? Individuals who have different preexisting characteristics tend to select different educational paths. For example, research shows that women are more likely than men to attend PSE (Shaienks, Gluszynski, & Bayard, 2008). Students with higher levels of parent education and better high school grades are more likely to enroll in a university than a 2-year college (Shaienks & Gluszynski, 2007; Tomkowicz & Bushnik, 2003). Two-year college students are more likely to live with their parents compared to 4-year students (Paschall, Bersamin, & Flewelling, 2005; Velazquez et al., 2011). Research suggests that the student body composition of 2-year colleges is more diverse in terms of age, ethnicity, and life stage than university campuses (Shaienks & Gluszynski, 2007; Sheffield, Darkes, Del Boca, & Goldman, 2005; Velazquez et al., 2011). Further, transfer students tend to fall “in-between” university students and terminal high school graduates with respect to socioeconomic status (SES) and high school grades and often begin at a 2-year college because of lower tuition fees, smaller class sizes, and a failure to achieve the high school grades required for direct entry into university (Cowin, 2013; Provasnik & Planty, 2008). Thus, drinking may be different across postsecondary institutions because of differences in the characteristics of the students that enroll.

Drinking may also differ across educational settings because of variation in contextual factors, which expose individuals to different environmental experiences. Universities have a more well-defined campus culture than community colleges that provides greater access and more social-based opportunities for student drinking, such as living on campus in student housing, campus bars, and campus sporting events (Borsari & Carey, 2001; Reifman et al., 2010; Sheffield et al., 2005). Differences in drinking between types of education settings would suggest a need to target institution-specific risk factors to reduce drinking and related harms on postsecondary campuses.

Rates of drinking and alcohol-related harms are high among both community college students and university students (Jackson et al., 2005; Sheffield et al., 2005). However, only two studies have actually compared differences in drinking between community college students and university students (Timberlake et al., 2007; Velazquez et al., 2011). Following a sample of 7,082 adolescents (aged 13–24), Timberlake and colleagues (2007) found that 4-year students had the greatest increases in alcohol use and the highest drinking levels during young adulthood compared to 2-year college students, PSE dropouts, and individuals who never enrolled in PSE. In their cross-sectional study of 13,700 students, Velazquez et al. (2011) also found evidence that 4-year students, particularly males, had a higher prevalence of risky drinking compared to 2-year students. However, these differences were no longer significant after controlling for age, ethnicity, relationship status, dependent children, weekly hours worked, and living arrangement. Only one study has examined the trajectory of alcohol use for transfer students in comparison to other educational pathways. Using a community sample of 921 youth aged 15–23, Fleming, White, Haggerty, Abbott, and Catalano (2012) found that, at age 19, the 4-year university students had higher levels of heavy drinking compared to transfer students, but transfer students had significantly greater acceleration in heavy drinking after age 19. Overall, the findings suggest that dichotomizing young adults into “students” and “nonstudents” may conceal important subgroup differences. As a result, little is known about the trajectory of drinking for young adults who do not pursue a degree at a 4-year university. For example, do 2-year college students also experience steep increases in alcohol consumption after enrollment?

The Timing of Postsecondary Enrollment

Both alcohol use and enrollment in PSE are age related. Alcohol use increases most before and when individuals reach the legal drinking age, which coincides with average age of enrollment in PSE (Bozick & DeLuca, 2005; Hango, 2011; Maggs & Schulenburg, 2005; Thompson et al., 2014). However, not all youth enroll in PSE directly out of high school. In Canada, 50% of youth who enrolled in PSE did so within 3 months, 73% within 15 months, and 81% within 28 months (Hango, 2011). Similar rates are reported in studies using recent cohorts in the United Kingdom (Crawford & Cribb, 2012), the United States (Bozick & DeLuca, 2005), and Australia (Curtis, Mlotkowski, & Lumdsen, 2012). Moreover, the average age of enrollment in PSE differs across types of institutions. Findings from Canada and the United States show that students who attend university typically enroll within a few months of high school completion, whereas those attending colleges or other institutions are more likely to delay their enrollment (Bozick & Deluca, 2005; Cowin, 2013). Several U.S. studies have noted that university students are typically 2 to 3 years younger when they enter PSE compared to those attending other institutions (O’Rand, Hamil-Liker, & Elman, 2009; Velazquez et al., 2011).

Research to date has not examined the association between the age of PSE enrollment and alcohol use. However, there are several reasons to expect that those who are older when they enroll may not experience the same acceleration in their alcohol consumption as those who enroll immediately after high school. For instance, family and work commitment may compete with leisure time and alcohol consumption for older students (Bachman, Wadsworth, O’Malley, Johnston, & Schulenberg, 1997). Moreover, older students may have already reached their developmental “peak” in alcohol use (Thompson et al., 2014). Thus, it may be that previous differences in drinking identified between types of postsecondary institutions reflect the characteristics of the students who enroll, such as age of enrollment, rather than contextual differences in the campus environments. If so, institutions may require different strategies to address their students’ vulnerability to alcohol use and related harms. For example, younger students have less drinking experience and as a result may have lower levels of tolerance for intoxication and be more vulnerable to injury, whereas that may be less likely for older students who typically have more drinking experience.

The Current Study

This study extends the current literature in several important ways. First, we distinguish between several different types of educational paths including 2-year community college, 4-year university, and transfer programs, as well as include young adults who do not attend PSE. Second, this is the first study to consider how age of enrollment may relate to trajectories of alcohol use. Third, we extend the predominantly U.S. literature on alcohol use and PSE by using a Canadian sample. Using longitudinal data spanning from adolescence to the mid-20s, this study asked the following questions: (1) Does the trajectory of alcohol use before enrollment in PSE and after enrollment in PSE differ for young adults who enroll in different types of postsecondary institutions (2-year college, 4-year university, or transfer)? (2) Does between-person variability in age at the time of enrollment affect the trajectory of alcohol use and account for differences in alcohol use between educational settings? (3) How do the trajectories of alcohol use for the different types of postsecondary institutions compare with the trajectory of alcohol use for young adults who do not attend PSE?

Given that preexisting individual characteristics such as gender, parent education, high school grades, and living situation predict type of PSE and alcohol use (Bozick & DeLuca, 2005; Hango, 2011; Homel, Thompson, & Leadbeater, 2014; Tomkowicz & Bushnik, 2003), our models included these variables as both control variables and for substantive interest in their own right.

Method

Participants

The Victoria Healthy Youth Survey is a five wave multicohort study of young people aged between 12 and 27. Participants were recruited from a medium-sized Canadian city using random digit dialing of 9,500 private telephone listings. Of the 1,036 eligible households with an adolescent aged 12–18, 662 adolescents (M = 15.52; SD = 1.93; 51% female) agreed to participate (64%). Participants were assessed biennially between 2003 and 2011. Response rates were 87% at Wave 2, 81% at Wave 3, 70% at Wave 4, and 70% at Wave 5. Distribution by age cohort at Wave 1 was as follows: age 12, n = 83 (13%); age 13, n = 90 (14%); age 14, n = 104 (16%); age 15, n = 98 (15%); age 16, n = 104 (16%); age 17, n = 112 (17%); and age 18, n = 71 (11%). The sample was 85% Caucasian, 4% Asian, 4% mixed/biracial, 3% Aboriginal, and 4% other. Nineteen percent of fathers and mothers finished high school only, and 43% of fathers and 49% of mothers completed college or university training. Parents or guardians gave consent whether youth were under 18 and youth consented at each wave. Trained interviewers administered surveys and respondents received a $35 honorarium per interview. The living situation, parental education, and ethnicity reported by participating youth were almost identical to that of the population from which the sample was drawn (Albrecht, Galambos, & Jansson, 2007). The University of Victoria Human Research Ethics Board approved this study (protocol number 09-292).

Our analytic sample was restricted to 521 participants that had data at Waves 4 or 5 when detailed information about PSE was collected and college status could be determined. Seventy-two percent of the sample had five waves of data, 21% had four waves, and 7% had two or three waves. Compared to the 141 youth who had dropped out by Waves 4 or 5, our subsample of 521 participants reported higher grades at Wave 1 (M = 3.11 vs. 2.81), F(1, 657) = 17.01, p = .001 (d = 0.38), and higher levels of maternal education (M = 2.98 vs. 2.56), F(1, 641) = 9.79, p = .002 (d = 0.30). There were no differences in gender, χ2(1, N = 662) = 3.50, p = .06, age at Wave 1, F(1, 660) = 0.14, p = .71, and frequency of heavy episodic drinking (HED) at Wave 1, F(1, 659) = 0.09, p = .77.

Measures

Alcohol use was measured using frequency of HED (Thompson, et al., 2014).1 Participants were asked to report “How often in the past 12 months have you had five or more drinks on one occasion?” The five possible response categories were as follows: 0 = never, 1 = a few times/year, 2 = a few times per month, 3 = once a week, and 4 = more than once a week.

Educational group

Participants were categorized into four groups. Two-year college (n = 124) included those who had enrolled in a subbaccalaureate program at a 2-year community college. Transfer (n = 88) included youth who reported being in a transfer program. In a transfer program, youth start their degree at a 2-year community college and transfer to a 4-year university to complete their degree. Four-year university (n = 180) included those who enrolled in a 4-year baccalaureate-granting university. Terminal high school graduates (n = 129) included participants who had not enrolled in any PSE by the final wave of the survey. Note that group membership was based on first enrollment rather than program completion, as many participants were still enrolled at the time of their last interview.

Age at the time of enrollment in PSE was calculated based on participants reported date of birth and the year they reported first enrolling in PSE.

Covariates included sex, maternal education, high school grades at Wave 1, and living arrangement at the time of PSE enrollment. Maternal education was a proxy for SES and had a 5-point scale that ranged from less than a high school diploma (=0) to finished college/university (=4). To assess high school grades, participants were asked, “In general, what are your grades right now?” with 5-point response options that ranged from 0 (mostly F’s) to 4 (mostly A’s). To assessment living arrangement, participants were asked to retrospectively provide data about which they were living with at each age. We matched participant’s living situation data to their reported age at the time of enrollment in PSE (and age 19 for the high school group). Living arrangement at the age of enrollment was categorized as “living with parents (0)” or “not living with parents (1).”

Data Preparation

To examine trajectories of alcohol use pre- and post PSE enrollment, we restructured the five waves of data to center the time metric on the event of enrolling in PSE. This allowed us to pinpoint the specific effect of going to PSE on the trajectory of drinking. For those who enrolled in a postsecondary institution by the end of the study (n = 392), zero was coded as the year participants reported enrolling in their first postsecondary institution. In the high school group, zero was age 19, which corresponded to the average age of PSE enrollment for the full sample. Although no single participant provided more than five repeated measures, our 521 participants provided a total of 2,366 observations to estimate a trajectory of alcohol use spanning 17 years (−8 years pre-enrollment to 8 years post-enrollment). However, 210 observations at the earliest and latest time points were dropped from the analysis due to poor model convergence yielding a total of 2,156 observations (N = 521). Eighty-seven percent of the sample (n = 457) had a least one data point pre- and post-enrollment in PSE.

Plan of Analyses

Piecewise latent growth curve models were used to model the trajectory of alcohol use over time (Li, Duncan, Duncan, & Hops, 2001). Slope pre described changes in alcohol use pre-entry into PSE (or pre age 19 for the high school group) and Slope post corresponded with changes in alcohol use post-entry in PSE (or post age 19 for the high school group). The intercept was centered on year of PSE entry (age 19 for the high school group). We used a piecewise approach instead of a growth curve with higher order polynomials because it allowed us to directly test the effect of going to PSE on changes in alcohol use and make comparisons across groups in alcohol use during different time periods of interest.

First, we ran an unconditional growth model (Model 1) to examine the means and variances of the growth factors of alcohol use over time for the whole sample. We then created dummy coding variables for the educational groups, which were regressed on each of the growth parameters to test group differences in the trajectory of alcohol over time (Model 2). Next, we included the covariates (Model 3). Finally, we examined the influence of age at the time of enrollment (Model 4). Model 4 excluded the high school group because they did not have an age of enrollment. Sex by education group interaction effects (Sex × Each Education Dummy) on the growth parameters were also tested, but were not significant and did not improve model fit (Δχ2 = 14.06, Δdf =12, p = .30). Initial models used the university group as the reference group. However, analysis were repeated using the high school group and the college group as reference groups to test contrasts between all different pairs of educational paths.

We used the full information maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR), implemented as MLR in MPlus 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). This approach uses data from all available time points for a given case under the assumption that data are missing at random (as would multiple imputation), which allows missingness to be related to variables included in the analyses (Little, 2013). MLR also offers protection against inflated α values as a result of incomplete data, nonnormality, and small sample sizes (Rhemtulla, Brosseau-Liard, & Savalei, 2012; Savalei, 2010). Model fit indices were evaluated by the criteria outlined by Hu and Bentler (1999) comparative fix index [CFI] ≥ .95, Tucker–Lewis Index ≥ .95, and root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] ≤ .06).

Results

Characteristics of the Education Groups

Thirty-five percent of the sample enrolled in a university, 24% enrolled in a 2-year college, 17% enrolled in a transfer program, and 25% did not attend any type of PSE. Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics for each educational group. The 2-year college group had a greater proportion of males compared to all other groups. The 4-year university group had the highest grades during high school, followed by the transfer group and 2-year college group. The high school group had the lowest high school grades, as well as the lowest levels of maternal education compared to all other groups. Transfer students were significantly more likely to be living with parents at the time of enrollment compared to the high school group. Finally, significant group differences were found in the average age of enrollment. The university group was the youngest when they enrolled and the college group was the oldest.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample by Educational Pathway.

| Full Sample (N = 521) % | High School (n = 129) % | College (n = 124) % | Transfer (n = 88) % | University (n = 180) % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male1 | 46.4 | 47.3a | 59.7b | 37.5a | 41.1a |

| Living with parents at the time of enrollment2 | 65.3 M (SD) |

55.8a M (SD) |

66.9a,b M (SD) |

75.6b M (SD) |

65.9a,b M (SD) |

| Maternal education3 | 2.89 (1.38) | 2.48 (1.48)a | 2.97 (1.30)b | 2.98 (1.33)b | 3.32 (1.15)b |

| High school grades4 | 3.05 (0.79) | 2.56 (0.72)a | 2.91 (0.72)b | 3.18 (0.67)c | 3.61 (0.55)d |

| Age of enrollment5 | 19.06 (1.49) | — | 19.63 (1.71)a | 19.10 (1.48)b | 18.45 (0.88)c |

Note. Estimates that do not share a superscripted letter significantly differ from one another. The high school group does not have an age of enrollment because they have not enrollment in a postsecondary education program.

Δχ2(df = 3) = 13.66, p = .003.

Δχ2(df = 3) = 9.31, p = .03.

F(3, 508) = 10.20, p = .001.

F(3, 515) = 68.52, p = .001.

F(2, 386) = 29.61, p = .001.

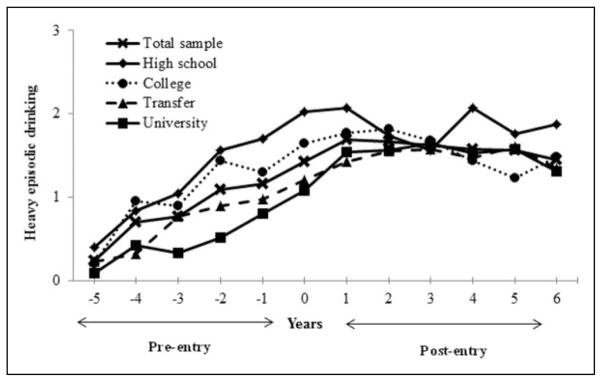

Figure 1 plots the observed means of HED for the total sample and for each education group over time. Group differences in mean levels of heavy drinking were found pre-enrollment, at years: −3, F(3, 173) = 4.72, p = .003; −2, F(3, 199) = 10.27, p = .0001; −1, F(3, 214) = 6.64, p = .0003; 0, F(3, 260) = 8.46, p = .0001. Overall, the high school and 2-year college group had higher mean levels of HED compared to the transfer group and university group. Table 2 shows the correlations among HED and the covariates.

Figure 1.

Observed means of heavy drinking for each education group over time (N = 521).

Table 2.

Correlations Between Heavy Episodic Drinking (HED) and Covariates.

| Sex | Mother’s Education | Age of Enrollment | High School Grades | Living Away From Parents at the Time of Entry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (0 = male) | — | — | — | — | |

| Mother’s education | 0.01 | — | — | — | |

| Age of enrollment | −0.06 | −0.09 | — | — | — |

| High school grades | 0.22** | 0.18** | −0.37** | — | — |

| Living with parents | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.29** | −0.09* | — |

| HED −5 years | 0.09 | −0.06 | 0.47** | −0.17 | 0.10 |

| HED −4 years | −0.02** | −0.03 | 0.51** | −0.37** | 0.25** |

| HED −3 years | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.29** | −0.33** | 0.02 |

| HED −2 years | −0.20** | −0.06 | 0.35** | −0.26** | 0.25** |

| HED −1 years | −0.18** | −0.10 | 0.25** | −0.26** | 0.13 |

| HED 0 (year of entry) | −0.30** | −0.06 | 0.29** | −0.27** | 0.18** |

| HED 1 years | −0.24** | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.12 | 0.08 |

| HED 2 years | −0.27** | −0.01 | 0.14* | −0.15* | 0.12 |

| HED 3 years | −0.26** | 0.14 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.09 |

| HED 4 years | −0.31** | −0.14 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.14 |

| HED 5 years | −0.26** | −0.01 | −0.09 | −0.004 | −0.05 |

| HED 6 years | −0.21* | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.12 | 0.15 |

Note. N = 521. HED = heavy episodic drinking.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Group Differences in the Trajectory of Heavy Drinking

For the total sample, the frequency of HED significantly increased prior to PSE enrollment (Slopepre = 2.40, p < .001), increased immediately after PSE enrollment (Slopepost = 1.65, p < .001), peaked approximately 3 years post-enrollment and then significantly declined (quadratic = −2.75, p < .001; Table 3, Model 1). There was also significant between-individual variation in each of the growth factors.

Table 3.

Education Group Differences in Heavy Drinking Over Time.

| Model 1 (N = 521) | Model 2 (N = 521) | Model 3 (N = 508) | Model 41 (N = 383) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | |

| Linear slope pre-entry (Slopepre) | ||||

| Mean | 2.40 (0.15) *** | 2.01 (0.22)*** | 2.74 90.30)*** | 2.56 (0.34)*** |

| High school | 1.22a,b (0.37)*** | 1.34a,b (0.49)** | — | |

| College | 0.65b (0.40) | 0.32b (0.43) | 0.54 (0.43) | |

| Transfer | 0.10a (0.41) | 0.22a (0.46) | 0.58 (0.47) | |

| University | — | — | — | |

| Gender (1 = female) | −1.21 (0.31)*** | −1.04 (0.34)*** | ||

| SES | 0.02 (0.11) | 0.04 (0.13) | ||

| High school grades | 0.14 (0.26) | −0.15 (0.30) | ||

| Living arrangement (1 = not with parents) | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.46 (0.35) | ||

| Age of enrolment | −0.03 (0.01)* | |||

| Level at entry (intercept) | ||||

| Mean | 1.46 (0.06)*** | 1.07 (0.08)*** | 1.36 (0.17)*** | 1.45 (0.13)*** |

| High school | 0.97a,b (0.15)*** | 0.73a,b (0.18)*** | — | |

| College | 0.60b,c (0.14)*** | 0.36b (0.15)* | 0.21 (0.16) | |

| Transfer | 0.15a,c (0.15) | 0.15a (0.15) | 0.08 (0.16) | |

| University | — | — | — | |

| Gender (1 = female) | −0.52 (0.11)*** | −0.51 (0.12)*** | ||

| SES | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.05) | ||

| High school grades | −0.15 (0.09) | −0.15 (0.10) | ||

| Living arrangement (1 = not with parents) | 0.36 (0.11)*** | 0.28 (0.14)* | ||

| Age of enrolment | 0.01 (0.01)* | |||

| Linear slope post-entry (Slopepost) | ||||

| Mean | 1.65 (0.35) *** | 3.44 (0.49)*** | 3.66 (0.78)*** | 3.58 (0.89)*** |

| High school | −4.69a (0.88)*** | −3.75a (1.19)** | — | |

| College | −2.80 (0.89)** | −2.25 (1.05)* | −1.49 (1.13) | |

| Transfer | −1.33a (1.01) | −0.71a (1.08) | −0.42 (1.10) | |

| University | — | — | — | |

| Gender (1 = female) | −1.11 (0.69) | −1.64 (0.76)* | ||

| SES | 0.16 (0.27) | −0.12 (0.31) | ||

| High school grades | 0.80 (0.56) | 0.48 (0.64) | ||

| Living arrangement (1 = not with parents) | −0.41 (0.75) | −0.06 (0.91) | ||

| Age of enrollment | −0.07 (0.03)** | |||

| Quadratic change post-entry | ||||

| Mean | −2.75 (0.64)*** | −5.21 (0.87)*** | −5.75 (1.38)*** | −6.17 (1.65)*** |

| High school | 6.40a (1.58)*** | 5.44a (2.16)* | — | |

| College | 3.71 (1.70)* | 3.30 (2.01) | 2.47 (2.20) | |

| Transfer | 1.97a (1.79) | 1.49a (1.94) | 1.16 (1.99) | |

| University | — | — | — | |

| Sex (1 = female) | 1.83 (1.25) | 2.85 (1.37)* | ||

| SES | −0.27 (0.49) | 0.20 (0.54) | ||

| High school grades | −0.82 (1.03) | −0.60 (1.20) | ||

| Living arrangement (1 = not with parents) | 0.25 (1.40) | −0.20 (1.72) | ||

| Age of enrollment | 0.05 (0.06) | |||

| Variance | ||||

| Slopepre | 4.34 (1.14)*** | 4.00 (1.07)*** | 1.00 (0.10)*** | 0.97 (0.11)*** |

| Intercept | 1.26 (0.11)*** | 1.10 (0.11)*** | 4.01 (0.71)*** | 4.51 (0.70)*** |

| Slopepost | 17.54 (5.20)** | 15.03 (25.01)** | 15.32 (4.97)** | 19.67 (5.25)*** |

| Quadratic | 39.33 (16.74)* | 36.49 (16.45)* | 36.09 (17.06)* | 47.64 (18.84)* |

| Covariances | ||||

| Slopepre with | ||||

| Intercept | 1.88 (0.32)*** | 1.67 (0.30)*** | 1.64 (0.26)*** | 1.87 (0.28)*** |

| Slopepost | 0.50 (1.98) | 1.27 (1.85) | 0.51 (1.66) | −2.63 (1.70) |

| Quadratic | −2.30 (3.37) | −2.93 (3.23) | −1.89 (3.00) | 2.72 (3.13) |

| Intercept with | ||||

| Slopepost | −1.29 (0.62)* | −0.64 (0.59) | −0.82 (0.57) | −1.15 (0.58)* |

| Quadratic | 0.93 (0.97) | 0.15 90.94) | 0.49 (0.94) | 0.96 (0.93) |

| Slopepost with | ||||

| Quadratic | −24.81 (8.81)** | −22.00 (8.61)* | −22.18 (8.75)* | −29.08 (9.43)** |

| Model fit2 | ||||

| χ2 | 122.20*** | 148.02*** | 181.91*** | 103.86 |

| df | 62 | 86 | 119 | 83 |

| RMSEA | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| CFI | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

Note. CFI = comparative fix index; Coeff. = regression coefficient; RMSEA = root mean squared error of approximation; SE = standard error; SES = socioeconomic status.

Model 4 excluded the high school group because they did not have an age of enrollment (N = 383). Models were first tested using university as the reference group and parameter estimates represent significant differences between the university group and all other educational pathways. Analyses were repeated using the high school group and the college group as reference groups to contextualize group differences.

A shared superscripted letter indicates significant differences (p < .05) between pairs of educational paths from these analyses.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

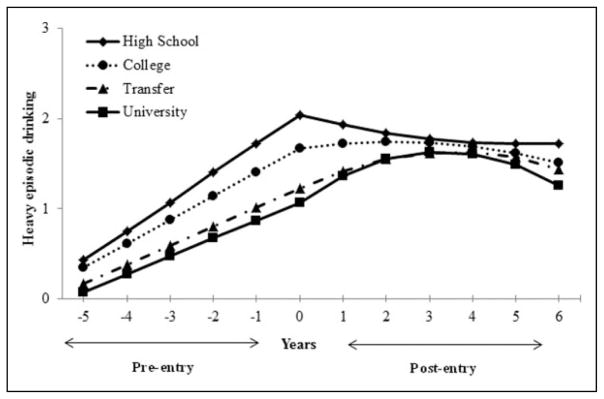

Figure 2 shows the estimated alcohol trajectories for the four educational pathways based on the parameter estimates from Model 2. All four groups significantly increased in the frequency of HED prior to enrollment. After enrollment in PSE, the high school group significantly declined in HED, the 2-year college group stabilized, and the transfer and university group significantly increased in HED.

Figure 2.

Estimated piecewise growth trajectories of heavy episodic drinking (HED) for each education group (N = 521).

Model 2 reports on significant differences in HED trajectories among the four groups over time. The high school group had significantly faster increases in HED pre-enrollment (Slopepre) than the three postsecondary groups, but there were no differences in the rate of increase in HED pre-enrollment between college, transfer, and university students. At the time of enrollment (intercept), the high school group had significantly higher levels of HED compared to all three postsecondary groups, and the college group had significantly higher levels of HED compared to the transfer and university students. Post-enrollment (Slopepost), the university group and transfer group had significantly greater increases in HED compared to the college group and the high school group, but did not exceed the drinking levels of the college and high school group at any time. Rather, university and transfer students “catch-up” to the drinking levels of their college and high school group peers and drinking levels converge across groups. However, the university group did have significantly faster deceleration (quadratic) in HED than the college group and high school group approximately 3 years after enrollment. There were no significant differences in any of the growth parameters of HED between the university group and the transfer group.

Model 3 examined the associations between HED and sex, maternal education, high school grades, and living arrangement. There were few main effects of these covariates on the trajectory of heavy drinking. Males had steeper increases in HED pre-enrollment (Slopepre = −1.21, p < .001) and higher levels of HED at the time of enrollment compared to females (intercept = −.52, p < .001). Also, students who were living with their parents during their first year of enrollment in PSE had lower levels of HED at enrollment (Intercept = .36, p < .001). However, after accounting for the effects of these covariates, differences in rates of change and levels of HED among the four groups remained significant. The single exception was that the difference in level of HED (intercept) between the college group and transfer group was no longer significant (p = .07).

Does How Old You Are at the Time of Enrollment Matter?

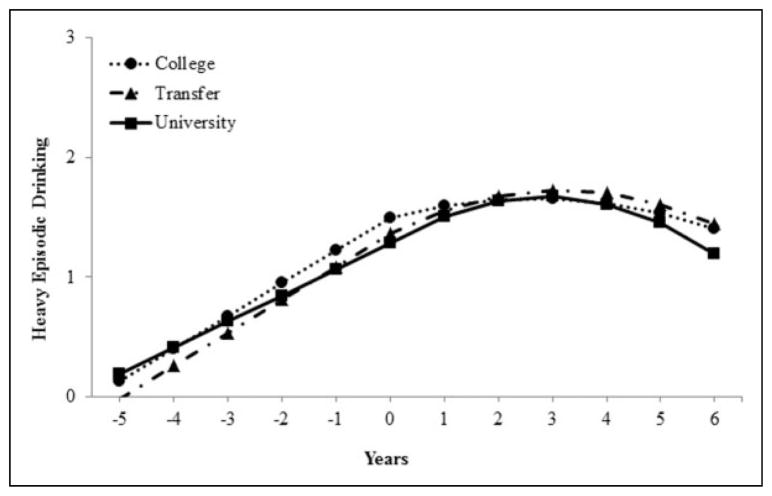

Model 4 examined the association between age at the time of enrollment and heavy drinking. Youth who were older when they enrolled in PSE had slower increases in heavy drinking prior to enrollment (Slopepre = −.03, p = .02), higher levels of heavy drinking when they enrolled (Intercept = .01, p = .03), and slower increases in heavy drinking following enrollment (Slopepost = −.07, p = .007) compared to younger students. Age of enrollment was not significantly associated with deceleration (quadratic) in HED. After accounting for age of enrollment, differences in the trajectories of HED between the college, transfer, and university groups were no longer significant. As shown in Figure 3, the rate of change and level of HED were the same across college, university, and transfer students over time. Also, Figure 3 showed that HED continued to escalate in a linear way following enrollment, as opposed to the expected acceleration in the trajectory of HED precipitated by the transition into PSE.

Figure 3.

The estimated trajectory of heavy drinking for the college, transfer and university group after accounting for age of enrollment, high school grades, living arrangement, sex, and maternal education (Model 4, N = 383).

Discussion

Few other studies have investigated differences in heavy drinking between types of PSE, and this study is the first to examine how age of enrollment relates to trajectories of alcohol use. This study found that between-person differences in age of enrollment accounted for differences in the trajectories of HED between different types of postsecondary settings. Overall, heavy drinking continued to increase steadily after enrollment in PSE and increased similarly across the different types of postsecondary settings. However, students who enrolled at a younger age had steeper increases in heavy drinking after enrollment than older students. Nevertheless, the terminal high school graduates had the highest and most persistent levels of heavy drinking over time compared to 2-year college students, 4-year university students, and transfer students.

Are There Differences in the Trajectory of HED for Students Attending Different Types of Postsecondary Programs?

Prior to accounting for age of enrollment, there were differences among 2-year college students, 4-year university students, and transfer students in levels of heavy drinking at the time of enrollment, and differences in the rate of growth in heavy drinking after enrollment. Consistent with the few U.S. studies that have examined differences between types of postsecondary settings, 4-year university students had significantly greater increases in HED compared to 2-year college students during the transition to PSE (Paschall et al., 2005; Timberlake et al., 2007). However, the university students never exceeded the drinking levels of the 2-year college students, but rather just “caught-up” to the drinking level of college students approximately 3 years post-enrollment. Importantly however, differences in age at the time of enrollment completely accounted for differences in heavy drinking across the three education groups. Thus, rather than differences in heavy drinking between postsecondary settings reflecting contextual variations across institutions, the current findings suggest that individual differences in the age of students at these institutions may account for institutional variation in drinking patterns. Moreover, the findings provide little evidence that enrollment itself precipitates an increase in heavy drinking. Rather the trajectory of heavy drinking during college appeared to be largely a linear extension of the pattern of drinking established prior to enrollment, consistent with findings from Sher and Rutledge (2007).

In our sample, 2-year college students were on average 1.2 years older than 4-year university students and 0.5 years older than transfer students when they enrolled. Further, 2-year college students had the greatest variability in age of enrollment (range = 17 to 26 years of age). Thus, because 2-year college students tended to be older when they enrolled, they had higher levels of use at the time of enrollment and experienced less of an increase in heavy drinking following enrollment. The apparent “catching up” of 4-year university students drinking levels to their 2-year college peers reflected the younger average age at enrollment of the 4-year university sample. Overall, students who enrolled at a younger age experienced significantly steeper increases in heavy drinking, regardless of the type of PSE they enrolled in.

The effect observed for age of enrollment on alcohol use is largely consistent with the normative age-graded trend in alcohol use that typically peaks in the early 20s and then declines. Students who enter PSE directly out of high school simply have much further to go in their drinking to reach their “peak” than students who have delayed enrollment. Student who are older when they enroll are also more likely to be of legal drinking age and may be balancing other responsibilities, such as employment, marriage and parenthood, that attenuate the effect of enrollment on increases in alcohol use (Bachman et al., 1997, 2002; Oesterle, Hawkins, Hill, & Bailey, 2011). Our findings suggest that the steeper increases in consumption among 4-year students that have previously been noted (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002; Slutske et al., 2004), could reflect the fact that 4-year students are more likely to enroll in PSE at an age when their alcohol use is increasing anyway. However, given that age of enrollment has not been previously examined, more research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Given that little previous research has included transfer students, it is interesting to note that even before accounting for age of enrollment there were no differences in trajectories of HED between transfer students and 4-year university students despite that transfer students start out at a 2-year college. This finding is somewhat surprising given the different contextual environments of 2-year and 4-year institutions (i.e., residential housing) theorized to explain group differences (Carter et al., 2010). It may be that there are individual-level similarities between transfer and 4-year university students that outweigh these contextual differences. For example, transfer students and 4-year university students may have similar educational aspirations during adolescence that might explain some of the similarities in their alcohol trajectories over time (Provasnik & Planty, 2008). Overall, the finding suggests that transfer students may be qualitatively different from other 2-year college students and that differentiating between them may be important for understanding links between education and well-being in young adulthood.

Do Postsecondary Students Drink More Than Their Nonstudent Peers?

The three postsecondary groups showed increases in alcohol consumption after enrollment, essentially “catching up” but not surpassing their nonstudent peers. This finding is consistent with several U.S. studies that found the rate of HED of terminal high school graduates to be equal to or higher than postsecondary students (Bingham, Shope, & Tang, 2005; Lanza & Collins, 2006; Reifman et al., 2010). The trajectory of heavy drinking diverged for terminal high school graduates from an early age. This group showed much steeper increases in alcohol consumption across adolescence. Moreover, at the time when most young adults were entering PSE (age 19) and increasing their frequency of heavy drinking, these young adults had reached their peak level of consumption and were starting to reduce their heavy drinking. However, despite this decline, their levels remained higher than all three postsecondary groups over time.

These young adults are quite distinct from those who attend PSE. In our sample, they had the lowest high school grades, the lowest maternal education, and the highest mean levels of alcohol use during adolescence. These earlier risk factors may close off options for pursuing higher education and lead to the early adoption of other adult roles (i.e., full-time employment) that are associated with decreases in alcohol use during young adulthood (Bachman et al., 1997). Given their early startup and persistent heavy drinking over time, this group of young people should be an important target for intervention efforts during the high school years as well as during young adulthood.

Limitations

This study used a random community sample and the ethnic makeup and economic diversity of our participants is consistent with the population sampled (Statistics Canada, 2001). Further, the prevalence of alcohol-related problems and alcohol use are similar to other Canadian studies (Health Canada, 2005). However, cross-cultural variations in macro-contextual factors, such as the legal drinking age and variations in structures of educational systems, need to be kept in mind when considering our findings and their implications. We need more international studies to improve our understanding of the link between alcohol and PSE during the transition to adulthood.

Despite examining dimensions of heterogeneity in educational paths that have received little attention in prior research, we opted not to further subdivide participants on the basis of other dimensions that may also be important (i.e., part-time or full-time status or dropouts vs. completers) due to the small percentage of part-time students and dropouts in each of the education groups. A larger sample size would facilitate examination of how heavy drinking is additionally influenced by these dimensions. Moreover, other factors such as whether students work full-time or part-time while attending PSE or whether they are married or have children could influence the relation between PSE and substance use and should be considered in future studies.

Additionally, many of the participants attended the same schools. Of those who attended a community college, 79% attended the community college in the city from which the sample was drawn. The majority (86%) of transfer students also started at this community college. Further, approximately 58% of the university group attended the same university. Students clustered in the same schools may confound the effects of pursuing different educational paths. There is a danger of attributing, for example, a 2-year community college effect to what may be a local effect. However, the proportion of our sample attending PSE (75%) and the proportion in each education groups were similar to national averages (Shaienks & Gluszynski, 2007). Nonetheless, we encourage further investigation of the relation between educational paths and alcohol use using youth from multiple institutions to improve the generalizability of findings. Also, future research might consider using nested models to account for the nesting of students within schools. Finally, the pairwise contrasts between education groups were determined using a dummy variable approach, rather than a multiple-group approach, because of the small sample size of the education groups. However, we caution that this approach could have resulted in alpha inflation and the findings should be replicated using larger samples.

Implications and Conclusions

It is clear that heavy drinking is not limited to a particular subset of young adults, such as those who go to university. Rather, our concern about heavy drinking and associated problems should be broader, recognizing the potential threat of alcohol misuse to all adolescents and young adults. Thus, community-based policy changes that strengthen enforcement of the legal drinking age, reduce the availability and access to low-cost alcohol, and limit exposure to alcohol marketing may be viable strategies for reducing alcohol use and related harm among this population (Gruenewald, 2011; Paschall, Grube, Thomas, Cannon, & Ryan, 2012). Also, given the strong pattern of continuity in drinking patterns following enrollment in PSE and the greater risk for younger students, interventions aimed at reducing heavy drinking and related harm may be most effective prior to or immediately following enrollment (i.e., during on-campus orientation activities) (Doumas, Kane, Navarro, & Roman, 2011; Sher & Rutledge, 2007).

Additionally, while the current findings show similar increasing trends in alcohol use across types of institutions, the factors associated with these increases may be quite different. For example, whereas increased alcohol use among 4-year university students may relate to living on-campus, this may not be relevant for understanding the drinking patterns of Canadian community college students who are largely non-residential (Sheffield et al., 2005). Moreover, variability in student body composition, particularly in terms of age, may require that the design and delivery of interventions be sensitive to characteristics of particular subgroups or settings. For example, while campus-wide initiatives may be useful on 4-year university campuses where there is a well-defined campus culture, they may not be applicable to community colleges where students spend less time on campus. Future work is needed to identify the unique individual and contextual factors that predict increases in alcohol use across subgroups of young adults and to identify optimal implementation strategies for delivery of interventions in different environmental contexts (i.e., college vs. university).

Conclusions

This is the first Canadian study to examine the longitudinal associations between PSE and alcohol use. The current findings suggest that the effect of PSE on increases in heavy drinking is largely contingent on the age of young adults at the time of enrollment, rather than the type of postsecondary setting they enroll in. However, the increase in heavy drinking following enrollment is still of concern. Steep increases in heavy drinking, particularly among younger students, may make it more likely that young people will experience injuries as a result of their drinking given their low levels of tolerance to high levels of intoxication. This study highlights the importance of age of enrollment on increases in drinking among students and it will be important for future research to consider how the timing of enrollment fits in with the larger social influences of attending PSE. Finally, we must not forget that terminal high school graduates appear to be the worst off given their high rates of early and persistent heavy drinking. We need to better understand how to engage with these young adults about alcohol use after they leave high school.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by grants (#838-20000-075, and #93533 to B. Leadbeater, PhD, #79917 to T. Stockwell, PhD, and #104612 to K. Thompson, PhD) from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

Biographies

Kara Thompson, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow at Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia, Canada. Her research interests include the development, antecedents, and consequences of substance use and mental health during the transition to adulthood and addiction policy. The present research was undertaken while she was a postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia, University of Victoria.

Tim Stockwell, PhD, is the director of the Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia and a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Victoria British Columbia Canada. His current research interests include the public health impacts of Canadian alcohol policies, managed alcohol programs for homeless problem drinkers, and the science underlying the hypothesis that moderate alcohol use promotes health.

Bonnie Leadbeater, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. She has made internationally recognized contributions to research on adolescent parenting, emerging adulthood, adolescent depression, resilience in high-risk youth, and the prevention of peer victimization in elementary school children.

Jacqueline Homel, PhD, is a research fellow at the Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne. She researches social and family determinants of successful developmental transitions during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood, particularly with regard to drug and alcohol use. The present research was undertaken while she was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Victoria, Canada.

Footnotes

Analyses were also run using volume (Frequency × Quantity). Findings were identical.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Albrecht AK, Galambos NL, Jansson SM. Adolescents’ internalizing and aggressive behaviors and perceptions of parents’ psychological control: A panel study examining direction of effects. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:673–684. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9191-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Association of Canadian Community Colleges. Transferability and post-secondary pathways. The role of Canadian Colleges and Institutes; Ottawa, Canada: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Bryant AL, Merline AC. The decline of substance use in young adulthood: Changes in social activities, roles, and beliefs. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham CR, Shope JT, Tang X. Drinking behavior from high school to young adulthood: Differences by college education. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:2170–2180. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000191763.56873.c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozick R, DeLuca S. Better late than never? Delayed enrollment in the high school to college transition. Social Forces. 2005;84:531–554. doi: 10.1353/sof.2005.0089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AC, Brandon KO, Goldman MS. The college and noncollege experience: A review of the factors that influence drinking behavior in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:742–750. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Dufour MC, Yi H. Alcohol consumption among young adults ages 18–24 in the United States: Results from the 2001–2002 NESARC survey. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004;28:269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Cowin B. Student transfer, success, and mobility in BC post-secondary institutions. A synthesis of research. British Columbia, Canada: British Columbia Council on Admissions and Transfer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford C, Cribb J. Gap year takers: uptake, trends and long term outcomes. London, England: Department for Education. Institute for Fiscal Studies through the Centre for Analysis of Youth Transitions (CAYT); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis D, Mlotkowski P, Lumdsen M. Bridging the gap: Who takes a gap year and why? Adelaide, SA, Australia: National Centre for Vocational Educational Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer C, Wardel J, Fuller R, Pampalone S, Steptoe S. International student of heavy drinking: Attitudes and sociodemographic factors in university students. Journal of American College Health. 2006;55:83–90. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.2.83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdall GW, Wechsler H. Studying college alcohol use: Widening the lens, sharpening the focus. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14(Suppl):14–22. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Kane CM, Navarro TB, Roman J. Decreasing heavy drinking in first-year students: Evaluation of a web-based personalized feedback program administered during orientation. Journal of College Counseling. 2011;14:5–20. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2011.tb00060.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Educational paths and substance use from adolescence into early adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2012;42:104–126. doi: 10.1177/0022042612446590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfroerer JC, Greenblatt JC, Wright DA. Substance use in the US college-age population: Differences according to educational status and living arrangement. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:62–65. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliksman L, Adlaf EM, Demers A, Newton-Taylor B. Heavy drinking on Canadian campuses. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2003;94:17–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03405045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ. Regulating availability: How access to alcohol affects drinking and problems in youth and adults. Alcohol research and health. 2011;34:248–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hango D. Delaying post-secondary education: Who delays and for how long? Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada, Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Canadian addiction survey (CAS): A national survey of Canadians’ use of alcohol and other drugs: Prevalence of use and related harms: Detailed report. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Homel J, Thompson K, Leadbeater B. Trajectories of marijuana use in youth aged 15 to 25: Implications for postsecondary education experiences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:674–683. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Park A. Drinking among college students: Consumption and consequences. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism, Vol. 17: Alcohol Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2005. pp. 85–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam E, Kypri K, Salamoun M. Alcohol use among college students: An international perspective. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20:213–221. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280fa836c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Paschall MJ, Langley J, Baxter J, Cashell-Smith M, Bourdeau B. Drinking and alcohol-related harm among New Zealand university students: Findings from a National Web-Based Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and experimental research. 2009;33:307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Collins LM. A mixture model of discontinuous development in heavy drinking from ages 18 to 30: The role of college enrollment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2006;67:552–561. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Duncan T, Duncan S, Hops H. Piecewise growth mixture modeling of adolescent alcohol use data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2001;8:175–204. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0802_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little T. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: The Gilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maggs J, Schulenberg J. Initiation and course of alcohol consumption among adolescents and young adults. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism, Vol. 17: Alcohol problems in adolescents and young adults. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2005. pp. 29–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. The development of heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems from ages 18 to 37 in a US national sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2000;61:290–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S, David Hawkins J, Hill KG, Bailey JA. Men’s and women’s pathways to adulthood and their adolescent precursors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:1436–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand AM, Hamil-Luker J, Elman C. Childhood adversity, educational trajectories, and self-reported health in later life among US women and men at the turn of the century. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft. 2009;12:409–436. doi: 10.1007/s11618-009-0081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Bersamin M, Flewelling RL. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between college attendance and heavy alcohol use: A national study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2005;66:266–274. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Grube JW, Thomas S, Cannon C, Treffers R. Relationships between local enforcement, alcohol availability, drinking norms, and adolescent alcohol use in 50 California cities. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2012;73:657–665. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provasnik S, Planty M. Community colleges: Special supplement to the condition of education 2008 (NCES 2008-033) Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Ro H, Barnes G, Feng D. Drinking in youth ages 13–21 attending and not attending college. Journal of the First-Year Experience & Students in Transition. 2010;22:67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rhemtulla M, Brosseau-Liard PÉ, Savalei V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods. 2012;17:354. doi: 10.1037/a0029315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savalei V. Small sample statistics for incomplete nonnormal data: Extensions of complete data formulae and a Monte Carlo comparison. Structural Equation Modeling. 2010;17:241–264. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2002;14(Suppl):54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaienks D, Gluszynski T. Participation in postsecondary education: Graduates, continuers and drop outs: Results from YITS cycle 4. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada, Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shaienks D, Gluszynski T, Bayard J. Postsecondary education, participation and dropping out: Differences across university, college and other types of postsecondary institutions. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada, Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sher K, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield FD, Darkes J, Del Boca FK, Goldman MS. Binge drinking and alcohol-related problems among community college students: Implications for prevention policy. Journal of American College Health. 2005;54:137–141. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.3.137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Hunt-Carter EE, Nabors-Oberg RE, Sher KJ, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, … Heath AC. Do college students drink more than their non-college-attending peers? evidence from a population-based longitudinal female twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:530–540. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Census of population. 2001 Retrieved March 14, 2013, from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/english/census01/Products/standard/themes/DataProducts.cfm?S=1.

- Timberlake DS, Hopfer CJ, Rhee SH, Friedman NP, Haberstick BC, Lessem JM, Hewitt JK. College attendance and its effect on drinking behaviors in a longitudinal study of adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1020–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K, Stockwell T, Leadbeater B, Homel J. Association among different measures of alcohol use across adolescence and emerging adulthood. Addiction. 2014;109:894–903. doi: 10.1111/add.12499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkowicz J, Bushnik T. Who goes to post-secondary education and when: Pathways chosen by 20 year olds. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada, Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce Census Bureau. Current Population Survey (CPS), October, 1967 through 2011. 2012 Retrieved June 6, 2014, from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d12/tables/dt12_239.asp.

- Velazquez CE, Pasch KE, Laska MN, Lust K, Story M, Ehlinger EP. Differential prevalence of alcohol use among 2-year and 4-year college students. Addictive behaviors. 2011;36:1353–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, McMorris BJ, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KF, Abbott RD. Increases in alcohol and marijuana use during the transition out of high school into emerging adulthood: The effects of leaving home, going to college, and high school protective factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:810–822. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]