Abstract

Objective

Preoperative methods to estimate disease specific survival (DSS) for resectable gastroesophageal (GE) junction and gastric adenocarcinoma are limited. We evaluated the relationship between DSS and pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR).

Background

The patient’s inflammatory state is thought to be associated with oncologic outcomes and NLR has been used as a simple and convenient marker for the systemic inflammatory response. Previous studies have suggested that NLR is associated with outcomes.

Methods

A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained institutional database was undertaken to identify patients who underwent potentially curative resection for GE junction and gastric adenocarcinoma from 1998–2013. Clinicopathologic findings, pre-treatment leukocyte values, and follow-up status were recorded. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate DSS and Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the association between variables and DSS.

Results

We identified 1,498 patients who fulfilled our eligibility criteria. Univariate analysis showed that male gender, Caucasian race, increased T and N stage, GE junction location, moderate/poor differentiation, non-intestinal Lauren histology, vascular and perineural invasion were associated with worse DSS. Elevated NLR was also associated with worse DSS (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.08–1.14; P<0.01). On multivariate analysis, pre-treatment NLR as a continuous variable was a highly significant independent predictor of DSS. For every unit increase in NLR, the risk of cancer-associated death increases by approximately 10% (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.05–1.13; P<0.0001).

Conclusion

In patients with resectable GE junction and gastric adenocarcinoma, pre-treatment NLR independently predicts DSS. This and other clinical variables can be used in conjunction with cross-sectional imaging and endoscopic ultrasound as part of the preoperative risk stratification process.

MINI ABSTRACT

Preoperative methods to estimate disease specific survival (DSS) for resectable gastroesophageal (GE) junction and gastric adenocarcinoma are limited. We found that pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) independently predicted DSS. This and other clinical variables can be used in conjunction with cross-sectional imaging and endoscopic ultrasound as part of the preoperative risk stratification process.

INTRODUCTION

Neoadjuvant therapy improves survival for patients with resectable gastroesophageal (GE) junction and gastric adenocarcinoma.1, 2 Preoperative therapy may be more appropriate for patients who are at higher risk for systemic failure as patients with early stage disease have a high chance of cure with surgical resection alone.3 Thus, accurate pre-treatment staging is essential to inform the decision about neoadjuvant therapy. Unfortunately, preoperative staging methods such as serum tumor markers, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and computed tomography (CT) scans are only moderately accurate.4–7 More tools to risk stratify patients before treatment initiation are needed.

The patient’s inflammatory state is thought to be associated with oncologic outcomes, as suggested by the consistent association of decreased disease specific survival (DSS) with postoperative complications8–11 or the presumed immunomodulatory effect of red blood cell transfusions.12–14 Systemic inflammation leads to relative neutrophilia and lymphocytopenia.15–17 As a result, the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has been used as a simple and convenient marker for the systemic inflammatory response.15

Elevated NLR is associated with worse survival in wide variety of malignancies including colorectal cancer,18 pancreatic cancer,19 gastrointestinal stromal tumor,20 hepatocellular carcinoma,21 non small cell lung cancer,22 ovarian cancer,23 multiple myeloma,24 and renal cell carcinoma.25 Previous studies have also linked NLR to gastric cancer outcomes.26–28 However, these reports are hampered by small sample size or limited statistical analyses. The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between DSS and pre-treatment NLR in a large uniform cohort of patients with curatively resected GE junction and gastric adenocarcinomas in an effort to identify a new tool to risk-stratify patients to aid in clinical decision making.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database was performed to identify all patients who underwent potentially curative resection for GE junction and gastric adenocarcinoma between 1998 and 2013 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Patients with M1 disease, non-primary adenocarcinoma, or without pre-treatment complete blood count values were excluded. Clinicopathologic findings and follow-up status were documented. Neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte values obtained prior to the initiation of any treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation) were recorded. For patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy, post-treatment, preoperative leukocyte counts were also obtained. All laboratories values were measured within three months of initial treatment. The MSKCC institutional review and privacy board approved the study.

Disease specific survival was calculated from date of surgery to date of death from gastric cancer. Patients who died of causes unrelated to the disease were censored at the last follow-up. Survival was estimated by Kaplan-Meier methods. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to examine the effect of pre-treatment NLR as a continuous variable on DSS after adjusting for known confounders: age at surgery, T stage, N stage, and tumor location.29 The log-rank test was used to compare DSS between groups when the patients were stratified into quartiles based on NLR.

For patients who received neoadjuvant therapy, we used the sign test, which is a nonparametric method used to determine whether the medians of two continuous variables are different from each other in the presence of paired data (i.e. before and after treatment), to evaluate the difference in median WBC before and after neoadjuvant therapy.30, 31 All analyses were carried out using SAS (version 9.2. Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Elevated NLR was Associated with Worse Disease Specific Survival

A total of 1,848 patients were initially identified. We excluded 151 patients who had M1 disease or non-primary adenocarcinoma and 199 patients who did not have pre-treatment lab values available. The study cohort consisted of 1,498 patients and the median follow-up was four years. The median age was 66 years, with a range of 20 to 96. The median NLR was 2.8 (range, 0.2–30.3; IQR, 2.0–3.9). Median time from laboratory measurement to initiation of neoadjuvant therapy or operation was 7 days (range, 1–67 days; IQR, 4–13 days). One hundred and eighty-seven patients were censored at last follow-up for death unrelated to disease.

Univariate associations of clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment patterns to DSS are outlined in Table 1. Male gender, Caucasian race, proximal tumor location, tumor dedifferentiation, diffuse type histology, vascular involvement, perineural invasion, and higher T and N stages were significantly associated with worse outcomes (all P<0.01).

Table 1.

Association of Disease Specific Survival to Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Treatment Patterns

| Characteristic | N | % | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Surgery* | 1498 | 0.96 | 0.9–1.04 | 0.99 | |

| Gender | 0.01 | ||||

| Female | 569 | 38.0 | 1.00 | ||

| Male | 929 | 62.0 | 1.27 | 1.05–1.53 | |

| Race | <0.01 | ||||

| Non Caucasian | 371 | 24.8 | 1.00 | ||

| Caucasian | 1127 | 75.2 | 1.43 | 1.14–1.80 | |

| Location | <0.01 | ||||

| GE Junction | 435 | 29.0 | 1.00 | ||

| Upper Third | 247 | 16.5 | 0.98 | 0.75–1.30 | |

| Middle Third | 305 | 20.4 | 0.78 | 0.60–1.00 | |

| Lower Third | 480 | 32.0 | 0.56 | 0.44–0.70 | |

| Diffuse | 31 | 2.1 | 2.69 | 1.70–4.27 | |

| T Stage | <0.01 | ||||

| T1 | 467 | 31.2 | 1.00 | ||

| T2 | 213 | 14.2 | 4.00 | 2.60–5.88 | |

| T3 | 434 | 29.0 | 6.15 | 4.36–8.67 | |

| T4 | 319 | 21.3 | 11.7 | 8.30–16.5 | |

| T0 | 65 | 4.3 | 1.80 | 0.82–3.77 | |

| N Stage | <0.01 | ||||

| N0 | 787 | 52.6 | 1.00 | ||

| N1 | 272 | 18.2 | 2.74 | 2.10–3.56 | |

| N2 | 202 | 13.5 | 3.88 | 2.97–5.06 | |

| N3 | 235 | 15.7 | 7.70 | 6.10–9.72 | |

| Differentiation | <0.01 | ||||

| Well | 103 | 7.0 | 1.00 | ||

| Mod/Poor | 1379 | 93.0 | 8.36 | 3.73–18.7 | |

| Lauren | <0.01 | ||||

| Intestinal | 834 | 56.7 | 1.00 | ||

| Diffuse | 429 | 29.2 | 1.71 | 1.40–2.10 | |

| Mixed | 207 | 14.1 | 1.58 | 1.22–2.07 | |

| Vascular Invasion | <0.01 | ||||

| Absent | 823 | 54.9 | 1.00 | ||

| Present | 675 | 45.1 | 2.63 | 2.19–3.16 | |

| Perineural Invasion | <0.01 | ||||

| Absent | 881 | 58.8 | 1.00 | ||

| Present | 617 | 41.2 | 2.81 | 2.33–3.36 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval;

estimate for every 10 years increase in age

The associations of leukocyte counts with DSS are detailed in Table 2. Elevated neutrophil (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.10–1.19; P<0.01) and monocyte (HR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.62–4.33; P<0.01) counts were associated with worse DSS while increased lymphocytes were associated with improved survival (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.69–0.94; P<0.01). NLR was also significantly associated with worse DSS (HR, 1.11; 95% CI 1.08–1.14; P<0.01).

Table 2.

Association of Disease Specific Survival to Leukocyte Values

| Characteristic | Median | Range (IQR) | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil (K/mcl) | 4.5 | 0.7–18.2 (3.5–5.7) | 1.15 | 1.10–1.19 | <0.01 |

| Lymphocyte (K/mcl) | 1.6 | 0.4–15.0 (1.2–2.0) | 0.80 | 0.69–0.94 | <0.01 |

| Monocyte (K/mcl) | 0.4 | 0–2.4 (0.3–0.5) | 2.64 | 1.62–4.33 | <0.01 |

| NLR | 2.8 | 0.2–30.3 (2.0–3.9) | 1.11 | 1.08–1.14 | <0.01 |

K/mcl, thousand cells per microliter; IQR, interquartile range; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Elevated NLR Was Associated With Unfavorable Clinicopathologic Factors

We next assessed whether NLR was associated with patient and tumor characteristics (Table 3). Elevated NLR was related to many clinicopathologic variables previously shown to be associated with worse outcomes in GE junction and gastric adenocarcinomas.29 Median NLR were significantly higher in patients who were male, older than 66 years, and of Caucasian race. Patients with tumors at the GE junction, higher T stage, and higher N stage also had elevated NLR (all P<0.01).

Table 3.

Association of NLR to Clinicopathologic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Median NLR | Range | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort (N=1,498) | 2.76 | 0.23–30.3 | |

| Gender | <0.01 | ||

| Female | 2.47 | 0.44–19.4 | |

| Male | 3.00 | 0.24–30.3 | |

| Age at Blood Draw | <0.01 | ||

| <66 Years | 2.60 | 1.87–3.56 | |

| ≥66 Years | 3.00 | 2.11–4.10 | |

| Race | <0.01 | ||

| Non Caucasian | 2.33 | 0.24–19.4 | |

| Caucasian | 2.88 | 0.33–30.3 | |

| Location | <0.01 | ||

| GE Junction | 3.09 | 0.82–30.3 | |

| Upper Third | 2.83 | 0.33–29.2 | |

| Middle Third | 2.56 | 0.44–24.0 | |

| Lower Third | 2.64 | 0.24–15.4 | |

| Diffuse | 2.36 | 1.24–11.0 | |

| T Stage | <0.01 | ||

| T1 | 2.38 | 0.44–17.8 | |

| T2 | 2.69 | 0.89–14.2 | |

| T3 | 3.00 | 0.48–30.3 | |

| T4 | 3.00 | 0.24–29.2 | |

| T0 | 3.20 | 0.33–8.00 | |

| N Stage | <0.01 | ||

| N0 | 2.63 | 0.33–29.2 | |

| N1 | 2.93 | 0.77–17.1 | |

| N2 | 2.90 | 0.24–30.3 | |

| N3 | 2.88 | 0.55–19.4 | |

| Differentiation | 0.03 | ||

| Well | 2.56 | 0.33–7.88 | |

| Moderate/Poor | 2.79 | 0.24–30.3 | |

| Lauren | 0.02 | ||

| Intestinal | 2.85 | 0.33–30.3 | |

| Diffuse | 2.58 | 0.44–19.4 | |

| Mixed | 2.73 | 0.24–15.8 | |

| Vascular Invasion | 0.01 | ||

| Absent | 2.67 | 0.33–30.3 | |

| Present | 2.88 | 0.24–29.2 | |

| Perineural Invasion | 0.18 | ||

| Absent | 2.68 | 0.33–29.2 | |

| Present | 2.88 | 0.24–30.3 |

NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

Other pathologic factors associated with increased NLR were moderate/poor differentiation, intestinal Lauren histology, and vascular invasion. Although statistically significant, the absolute difference in NLR for these characteristics was smaller (10% change or less).

For the 508 patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy, there was a significant reduction in both neutrophil (−1.3 K/mcL (−27%); P<0.01) and lymphocyte (−0.4 K/mcL (−25%); P<0.01) counts after treatment. However, NLR did not change significantly (−0.1; P=0.86) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Leukocyte Values Before and After Neoadjuvant Treatment (N=508)

| Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil (K/mcL), Median (Range) | 4.8 (1.1–18.2) | 3.5 (0.4–15.2) | <0.01 |

| Lymphocyte (K/mcL), Median (Range) | 1.6 (0.5–15) | 1.2 (0.1–5) | <0.01 |

| Monocyte(K/mcL), Median (Range) | 0.4 (0–1.3) | 0.4 (0–1.4) | 0.88 |

| NLR, Median (Range) | 3.1 (0.3–30.3) | 3.0 (0.3–44.0) | 0.86 |

K/mcl, thousand cells per microliter

NLR Independently Predicted Disease Specific Survival

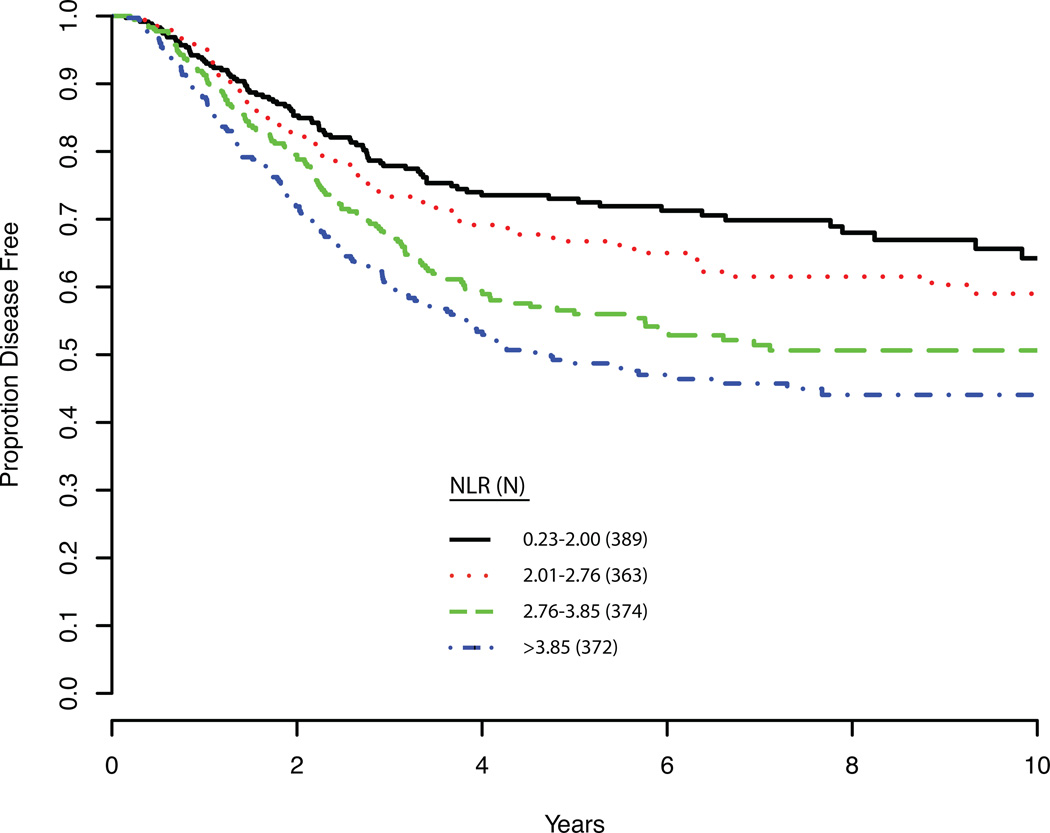

Finally, we performed a multivariate analysis to determine if NLR independently predicted DSS (Table 5). After adjusting for age at surgery, T stage, N stage, and tumor location, we found that pre-treatment NLR as a continuous variable was independently associated with DSS (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.05–1.13; P<0.0001). Tumor location, T stage, and N stage (all P<0.0001) also independently correlated with DSS. Analyses including pre-treatment monocyte count in the above multivariate model showed that it was not significantly associated with DSS (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.70–2.01; p=0.52). Even when we excluded pre-treatment NLR, there was still no significant association between monocyte count and DSS (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.78–2.36; p=0.29). Long-term DSS is shown for patients based on NLR stratified into quartiles (P<0.01; Figure 1).

Table 5.

Multivariate Analysis and Disease Specific Survival

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Surgery* | 1.02 | 0.95–1.10 | 0.53 |

| Pre-Treatment NLR | 1.10 | 1.05–1.13 | <0.0001 |

| T stage | <0.0001 | ||

| T1 | 1.00 | ||

| T0 | 1.40 | 0.65–3.01 | |

| T2 | 2.75 | 1.83–4.14 | |

| T3 | 3.18 | 2.21–4.59 | |

| T4 | 6.66 | 4.53–9.79 | |

| N Stage | <0.0001 | ||

| N0 | 1.00 | ||

| N1 | 1.84 | 1.39–2.43 | |

| N2 | 2.36 | 1.77–3.14 | |

| N3 | 4.12 | 3.15–5.37 | |

| Tumor Location | <0.0001 | ||

| GE Junction | 1.00 | ||

| Upper Third | 0.53 | 0.40–0.72 | |

| Middle Third | 0.45 | 0.30–0.60 | |

| Lower Third | 0.43 | 0.32–0.56 | |

| Diffuse | 0.90 | 0.54–1.51 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval;

estimate for every 10 years increase in age

Figure 1. Disease Specific Survival.

Disease specific survival is plotted as the patient cohort was divided into quartiles based on neutrophil to lymphocyte ratios. NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio.

DISCUSSION

This report is the largest series to show that NLR is an independent predictor of disease specific outcome in any cancer population. We found that elevated NLR is associated with a number of variables previously shown to be predictive of worse outcomes. These include patient characteristics such as male gender, older age, and Caucasian race and tumor features including higher T and N stage, poor differentiation, GE junction location, and vascular invasion. However, we also found that NLR as a continuous variable independently predicted DSS, which suggests that NLR may be a predictor of oncologic outcomes and may aid in the clinical decision-making process. We estimate that for every unit increase in NLR, there is an approximately 10% rise in risk for cancer-related death.

Previous reports on NLR were constrained by small or limited patient populations or the use arbitrary cutoff values. Specifically for gastric cancer, Yamanaka et al studied the association of NLR to survival in 1,220 non-surgical patients with stage 4 disease who were enrolled in prospective trials to evaluate the efficacy of S-1,32 while Shimada et al evaluated 1,028 patients with primary gastric adenocarcinoma who underwent gastrectomy.33 While both groups found that NLR was associated with survival, they dichotomized the study population with an arbitrary cut-off value limiting the statistical power of their analyses.

This is also the largest report with patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy. Preoperative systemic treatment for locoregional advanced gastric cancer significantly improves overall survival and is now widely utilized in the Western world.1 We found that patients who received neoadjuvant therapy had higher median pre-treatment NLR than patients who did not receive therapy. This is likely because patients who underwent systemic therapy tended to have higher stage disease. Indeed, we found that even though neutrophil and lymphocyte counts were significantly reduced after neoadjuvant therapy, the post-treatment, preoperative NLR was not significantly different than pre-treatment NLR and remained independently predictive of DSS (data not shown).

Accurate risk stratification is essential to determine if a given patient should receive preoperative systemic therapy. Overstaging unnecessarily exposes the patient to the morbidity of chemotherapy while understaging risks missing the opportunity to administer preoperative systemic therapy, as many patients cannot tolerate adjuvant therapy after gastrectomy.34–36 Currently, the most widely utilized preoperative staging tools are EUS and CT scans, both of which are of only modest utility. In a systematic review of the literature, Kwee and Kwee reported that accuracy in determining T stage ranged from 65–92% for EUS and 77–88% for CT scans.37 For nodal disease, they reported that median sensitivity and specificity for EUS were 71% and 85%, respectively, and 80% and 78%, respectively, for CT scans. However, the range for each measure was very wide.38

One of the main limitations of EUS is its high operator dependency. Bentrem et al reviewed the utility of EUS staging in predicting pathologic findings and outcomes. They found that EUS was only 57% accurate in determining individual T stage and only 50% accurate for N stage. More importantly, they noted only a modest predictive value in discriminating outcome when comparing uT1–3N0 to T4aNany patients.7 In addition, most reports on the staging utility of EUS and CT scan appear to be too optimistic as suggested by a population-wide analysis of gastric cancer treatment pattern reporting that up to 30% of patients have occult metastatic disease not appreciated on preoperative staging evaluation.39 In light of the limitations of EUS and CT scans, NLR could be a useful and easily obtainable variable to include in the preoperative evaluation of GE junction and gastric cancer patients. NLR could be especially important to help decide about neoadjuvant therapy in patients who are considered to be borderline candidates based on conventional imaging techniques.

Previous studies showed that pre-treatment levels of carcinoembryonic antigen, certain acute phase reactants, and nutritional markers independently predict outcomes in gastric cancer patients.4, 40 Our study demonstrated that pre-treatment NLR should be included on the list of pre-treatment factors that independently predicted disease specific outcomes after controlling for a wide variety of confounders.

The concept of inflammation as a localized pro-carcinogenic process dates back to the 19th century with Virchow’s observations. Currently, inflammation is thought of as a key enabling process for cells to acquire essential “hallmarks of cancer” that constitute the foundation of malignant transformation.41 However, studies demonstrating independent association of an activated acute inflammatory response and cancer specific outcomes suggest that there is also a correlation between the systemic inflammatory state, as broadly represented by the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, and oncologic progression.

For the surgical patient, infectious complications and blood transfusions are likely the most common postoperative causes of an activated inflammatory state. Multiple reports encompassing a variety of malignancies including breast,9 esophagus,10, 42 gastric,11 and colorectal,8, 43 have demonstrated that postoperative complications independently predict worse cancer specific outcomes. Significantly, these outcomes are not simply related to local recurrence and suggest an underlying systemic process.9, 11 Similarly, allogenic blood transfusions have also been shown to be independently associated with worse cancer specific outcomes.12, 13, 44 Interestingly, Weitz et al showed that in patients who underwent resection for Siewert II or III tumors, blood transfusions are associated with worse DSS only in patients who had an intact spleen, further implicating the immune process as the mediator between transfusions and oncologic outcomes.45

Several recent studies have provided a number of potential mechanisms to explain the prognostic power of neutrophilia in cancer patients. Bald et al reported that in melanoma, neutrophils infiltrate the primary tumor site and secrete factors that stimulate angiogenesis and induce cancer cells to migrate along these newly formed blood vessels, which may facilitate metastasis.46 Neutrophils have also been described to increase adhesion between circulating tumor cells and the end-organ, thus increasing the chance of metastatic seeding. Spicer et al described neutrophils acting as an adhesive adapter between circulating tumor cells and the metastatic target.47 Cools-Lartigue et al noted that neutrophil extracellular traps, which are composed of neutrophil-secreted chromatin and proteins, can capture circulating tumor cells leading to increased metastases in a mouse model.48

Lymphopenia has been associated with worse outcomes in cancer patients.49, 50 Previous studies have shown that lymphocytes may be responsible for generating an anti-tumor immune response. One example of this thesis is the clinical relevance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), the presence of which is associated with improved outcomes in a variety of cancers, possibly due to TIL-induced anti-tumor activity and inhibition of angiogenesis.51–53 The ability of immunotherapy to generate long-term and durable disease response, such as with the case of ipilimumab and melanoma, demonstrate the anti-oncogenic power of a mobilized adaptive immune system.54

CONCLUSIONS

In patients with resectable GE junction and gastric adenocarcinoma, pre-treatment NLR is significantly and independently associated with cancer specific survival. This and other clinical variables can be used to supplement cross-sectional imaging and EUS to better risk stratify patients prior to treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, et al. Perioperative Chemotherapy Compared With Surgery Alone for Resectable Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma: An FNCLCC and FFCD Multicenter Phase III Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:1715–1721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, et al. A Multicenter Study on Oncologic Outcome of Laparoscopic Gastrectomy for Early Cancer in Japan. Annals of Surgery. 2007;245:68–72. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225364.03133.f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Hokita S, et al. Clinical importance of preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels in gastric cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:41–44. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardoso R, Coburn N, Seevaratnam R, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the utility of EUS for preoperative staging for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15(Suppl 1):S19–S26. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasegawa S, Yoshikawa T, Shirai J, et al. A prospective validation study to diagnose serosal invasion and nodal metastases of gastric cancer by multidetector-row CT. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2016–2022. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2817-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentrem D, Gerdes H, Tang L, et al. Clinical correlation of endoscopic ultrasonography with pathologic stage and outcome in patients undergoing curative resection for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1853–1859. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker KG, Bell SW, Rickard MJFX, et al. Anastomotic Leakage Is Predictive of Diminished Survival After Potentially Curative Resection for Colorectal Cancer. Annals of Surgery. 2004;240:255–259. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133186.81222.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murthy BL, Thomson CS, Dodwell D, et al. Postoperative wound complications and systemic recurrence in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1211–1217. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagarde SM, de Boer JD, Kate ten FJW, et al. Postoperative Complications After Esophagectomy for Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus Are Related to Timing of Death Due to Recurrence. Annals of Surgery. 2008;247:71–76. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815b695e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tokunaga M, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, et al. Poor Survival Rate in Patients with Postoperative Intra-Abdominal Infectious Complications Following Curative Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;20:1575–1583. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2720-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acheson AG, Brookes MJ, Spahn DR. Effects of Allogeneic Red Blood Cell Transfusions on Clinical Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Annals of Surgery. 2012;256:235–244. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825b35d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu L, Wang Z, Jiang S, et al. Perioperative Allogenenic Blood Transfusion Is Associated with Worse Clinical Outcomes for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related immunomodulation (TRIM): an update. Blood Rev. 2007;21:327–348. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zahorec R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts--rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2001;102:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dionigi R, Dominioni L, Benevento A, et al. Effects of surgical trauma of laparoscopic vs. open cholecystectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:471–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Mahony JB, Palder SB, Wood JJ, et al. Depression of cellular immunity after multiple trauma in the absence of sepsis. J Trauma. 1984;24:869–875. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malietzis G, Giacometti M, Askari A, et al. A Preoperative Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio of 3 Predicts Disease-Free Survival After Curative Elective Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Annals of Surgery. 2014;260:287–292. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stotz M, Gerger A, Eisner F, et al. Increased neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio is a poor prognostic factor in patients with primary operable and inoperable pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:416–421. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez DR, Baser RE, Cavnar MJ, et al. Blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is prognostic in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:593–599. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2682-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mano Y, Shirabe K, Yamashita Y-I, et al. Preoperative Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Is a Predictor of Survival After Hepatectomy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Annals of Surgery. 2013;258:301–305. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318297ad6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinato DJ, Shiner RJ, Seckl MJ, et al. Prognostic performance of inflammation-based prognostic indices in primaryoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1930–1935. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams KA, Labidi-Galy SI, Terry KL, et al. Prognostic significance and predictors of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelkitli E, Atay H, Çilingir F, et al. Predicting survival for multiple myeloma patients using baseline neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio. Ann Hematol. 2013;93:841–846. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1978-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Martino M, Pantuck AJ, Hofbauer S, et al. Prognostic Impact of Preoperative Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Localized Nonclear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Urology. 2013;190:1999–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aizawa M, Gotohda N, Takahashi S, et al. Predictive Value of Baseline Neutrophil/Lymphocyte Ratio for T4 Disease in Wall-Penetrating Gastric Cancer. World J Surg. 2011;35:2717–2722. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung MR, Park YK, Jeong O, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor survival following resection in late stage gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:504–510. doi: 10.1002/jso.21986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ubukata H, Motohashi G, Tabuchi T, et al. Evaluations of interferon-γ/interleukin-4 ratio and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio as prognostic indicators in gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:742–747. doi: 10.1002/jso.21725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kattan MW, Karpeh MS, Mazumdar M, et al. Postoperative nomogram for disease-specific survival after an R0 resection for gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3647–3650. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conover WJ. Practical Nonparametric Statistics (ed 2) New York: Wiley & Sons; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendenhall W, Wackerly D, Scheaffer LR. Mathematical Statistics with Applications (ed 4) Boston: P.W.S-Kent; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamanaka T, Matsumoto S, Teramukai S, et al. The Baseline Ratio of Neutrophils to Lymphocytes Is Associated with Patient Prognosis in Advanced Gastric Cancer. Oncology. 2007;73:215–220. doi: 10.1159/000127412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimada H, Takiguchi N, Kainuma O, et al. High preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts poor survival in patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:170–176. doi: 10.1007/s10120-010-0554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bang Y-J, Kim Y-W, Yang H-K, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:315–321. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61873-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee J, Lim DH, Kim S, et al. Phase III Trial Comparing Capecitabine Plus Cisplatin Versus Capecitabine Plus Cisplatin With Concurrent Capecitabine Radiotherapy in Completely Resected Gastric Cancer With D2 Lymph Node Dissection: The ARTIST Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:268–273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakuramoto S, Arai K. Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Gastric Cancer with S-1, an Oral Fluoropyrimidine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;357:1810–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwee RM, Kwee TC. Imaging in local staging of gastric cancer: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:2107–2116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwee RM, Kwee TC. Imaging in assessing lymph node status in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:6–22. doi: 10.1007/s10120-008-0492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karanicolas PJ, Elkin EB, Jacks LM, et al. Staging laparoscopy in the management of gastric cancer: a population-based analysis. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2011;213:644–651. 651.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aurello P, Tierno SM, Berardi G, et al. Value of preoperative inflammation-based prognostic scores in predicting overall survival and disease-free survival in patients with gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1998–2004. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lerut T, Moons J, Coosemans W, et al. Postoperative Complications After Transthoracic Esophagectomy for Cancer of the Esophagus and Gastroesophageal Junction Are Correlated With Early Cancer Recurrence. Annals of Surgery. 2009;250:798–807. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bdd5a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McArdle CS, McMillan DC, Hole DJ. Impact of anastomotic leakage on long-term survival of patients undergoing curative resection for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1150–1154. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Shin DW, et al. Adverse effects of perioperative transfusion on patients with stage III and IV gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:5–12. doi: 10.1245/aso.2002.9.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weitz J, D’Angelica M, Gönen M, et al. Interaction of splenectomy and perioperative blood transfusions on prognosis of patients with proximal gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4597–4603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bald T, Quast T, Landsberg J, et al. Ultraviolet-radiation-induced inflammation promotes angiotropism and metastasis in melanoma. Nature. 2014;507:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature13111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spicer JD, McDonald B, Cools-Lartigue JJ, et al. Neutrophils Promote Liver Metastasis via Mac-1-Mediated Interactions with Circulating Tumor Cells. Cancer Research. 2012;72:3919–3927. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cools-Lartigue J, Spicer J, McDonald B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3446–3458. doi: 10.1172/JCI67484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fogar P, Sperti C, Basso D, et al. Decreased total lymphocyte counts in pancreatic cancer: an index of adverse outcome. Pancreas. 2006;32:22–28. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000188305.90290.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ray-Coquard I, Cropet C, Van Glabbeke M, et al. Lymphopenia as a Prognostic Factor for Overall Survival in Advanced Carcinomas, Sarcomas, and Lymphomas. Cancer Research. 2009;69:5383–5391. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pagès F, Berger A, Camus M, et al. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:2654–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azimi F, Scolyer RA, Rumcheva P, et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Grade Is an Independent Predictor of Sentinel Lymph Node Status and Survival in Patients With Cutaneous Melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:2678–2683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]