Abstract

Adolescence heralds a unique period of vulnerability to depressive symptoms. This longitudinal study examined relational victimization in adolescents’ peer relationships as a unique predictor of depressive symptoms among a primarily (85%) Caucasian sample of 540 youth (294 females) concurrently and across a 6-year period. The moderating effects of emotional support received from mothers, fathers, and peers on the association between relational victimization and adolescents’ depressive symptoms were also investigated. Findings revealed that adolescents who were relationally victimized consistently had higher depressive symptoms than their non-victimized peers. However, high levels of emotional support from fathers buffered this relationship over time. Emotional support from mothers and peers also moderated the longitudinal relationship between relational victimization and depressive symptoms, with high levels of support predicting increases in adolescents’ symptoms. Relational victimization presents a clear risk for depressive symptoms in adolescence, and emotional support may serve either a protective or vulnerability-enhancing role depending on the source of support.

Keywords: Emotional support, Fathers, Mothers, Peers, Depressive symptoms, Relational victimization, Adolescence

Introduction

Ample research has demonstrated that the experience of depressive symptoms among adolescents is both widespread and problematic. A 2004 report on the health and well-being of adolescents stated that 21–36% of 12–16 year-old males and females report “feeling depressed” (Boyce 2006). Alarming rates have also been obtained in research examining clinically diagnosable levels of depressive symptoms. A longitudinal study using the Canadian National Population Health Survey (NPHS; Galambos et al. 2004) found that approximately 11–21% of adolescents aged 12–23 years met criteria for a Major Depressive Episode. The lowest level of depressive symptoms occurred in the youngest (14 year-old) participants and symptoms increased over time. In contrast, both preschool and preadolescent school-age children show low rates of depression and depressive symptoms—generally less than 2% (Stalets and Luby 2006; Sterba et al. 2007). Moreover, depressive symptoms in adolescence have been linked to increased risk for suicide, suicide attempts, recurrent depressive episodes, psychiatric and medical hospitalizations, and risk-taking behaviors, as well as general maladjustment in adulthood (Nansel et al. 2001; Weissman et al. 1999). Clearly, adolescence represents a unique period of vulnerability to depressive symptoms. A better understanding of the mechanisms that lead to increases or decreases in symptoms is needed.

Recent research has identified aspects of adolescents’ peer relationships that may contribute to depressive symptoms during this time. Namely, peer victimization, which affects approximately 10–30% of children and adolescents in community-based samples, has emerged as a notable risk factor for the development of elevated depressive symptoms in adolescence (see Hawker and Boulton 2000). Physical forms of victimization typically decrease as children get older; however, the occurrence of non-physical forms, sometimes referred to as indirect, social, or relational victimization, continues into adolescence (Craig 1998; NICHD Early Child Care Network 2004). These latter terms denote slightly different versions of non-physical bullying, capturing a range of harmful behaviors that are directed toward peers’ social relationships. The present study focuses on relational victimization defined as a relationally-oriented form of victimization in which victims are harmed through hurtful manipulation of or damage to their peer relationships, reputation, or social status (Crick and Grotpeter 1996). This can include having rumors spread about oneself, being deliberately excluded from social exchanges and events, having friends threaten to withdraw their friendship if one does not comply with their demands, and other forms of social manipulation (Crick and Bigbee 1998). Compared to children, little is known about relational victimization in adolescence. In one study, however, as many as 51% of 13–15 year-olds reported being relationally victimized by their peers (Bond et al. 2001). Relational victimization thus persists into adolescence, and research is needed to better understand it and to identify potential avenues for intervention and prevention in this age group.

The current study hypothesizes that interpersonal resources—specifically, emotionally supportive parents and/or peers—buffer the interpersonal vulnerabilities associated with relational victimization in adolescence. Parental and peer emotional support predict direct decreases in adolescents’ depressive symptoms, particularly for females (e.g., Carbonell et al. 1998; Helsen et al. 2000). However, little research has examined the protective effects of emotionally supportive networks for relationally victimized adolescents. The current study addresses this gap by investigating the moderating effects of maternal, paternal, and peer emotional support on depressive symptoms in adolescents who experience peer relational victimization both concurrently and longitudinally over a 6-year period. Research investigating the influence of emotional support is warranted to better understand resilience in adolescents who are relationally victimized.

Interpersonal Risks: Associations Between Relational Victimization and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence

Peer victimization in general is linked to significant maladjustment, particularly depressive symptoms (see Olweus 1993; Hawker and Boulton 2000). In a meta-analysis of published cross-sectional studies examining the association between victimization and various forms of maladjustment, Hawker and Boulton (2000) found that, compared to other forms of adjustment (i.e., loneliness, generalized and social anxiety, global and social self-worth), peer victimization was most strongly associated with depression. This association was significant regardless of whether peers assigned or participants self-rated their victim status, with effect sizes ranging from .29 to an astonishing .81, respectively.

Research has also linked the experience of relational victimization to poor psychological adjustment in both childhood (e.g., Crick and Bigbee 1998; Crick et al. 1999; Crick and Grotpeter 1996) and adolescent samples (e.g., Baldry 2004; Leadbeater et al. 2006; Prinstein et al. 2001; Vuijk et al. 2007). For example, Baldry (2004) found that being the victim of relational aggression was the strongest predictor of depressive symptoms in a sample of Italian 11–15 year-olds, compared to physical victimization experiences and youth’s own levels of aggression. Lead-beater et al. (2006) also reported that relationally (and physically) victimized eighth- to tenth-graders had the highest levels of depressive symptoms compared to youth categorized as typical (low aggressive/low victimized), aggressive, or aggressive/victimized. In an ethnically diverse sample of adolescents in grades 9–12, Prinstein et al. (2001) found that relational victimization was uniquely associated with concurrent social-psychological maladjustment, including depressive symptoms, after accounting for physical victimization and youth’s own levels of aggression. Furthermore, the association between relational victimization and internalizing symptoms (i.e., depressive symptoms, loneliness, and low self-esteem) was greater in girls than boys. Similarly, Storch et al. (2003) found that relational victimization was uniquely related to depressive symptoms, after controlling for overt victimization, in a sample of 10–13 year-old Hispanic and African-American preadolescent girls, but not boys. These cross-sectional findings reveal a consistent link between relational victimization and depressive symptoms in adolescence.

Longitudinal research, while rare, supports this link. Vuijk et al. (2007) assessed levels of relational and physical victimization, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms in a sample of 448 children at 7, 10, and 13 years of age over a period of 3 years. Youth were also participants in a randomized controlled trial evaluation of the Good Behavior Game, an intervention designed to decrease disruptive classroom behaviors and increase pro-social behavior. Self-reported rates of physical and relational victimization among youth in the intervention group decreased compared to those in control groups, as did their symptoms of depression and anxiety. Reductions in depressive symptoms were uniquely accounted for by decreases in relational victimization, whereas reductions in anxiety were accounted for by decreases in both physical and relational victimization. Furthermore, the association between relational victimization and depressive symptoms was stronger for girls compared to boys. Thus, relational victimization appears to contribute over time to depressive symptoms in adolescence.

Together, past research findings suggest that relationally aggressive peer behaviors are distressful and hurtful for adolescents. Specifically, the experience of relational victimization is associated with elevated depressive symptoms in adolescence, both concurrently and across time. This relationship is consistent with the interpersonal theory of depression (Klerman et al. 1984), which posits that stressful interpersonal interactions explain the etiology and maintenance of depression. Findings also suggest that the link between relational victimization and depressive symptoms may be particularly strong for adolescent girls. This vulnerability is consistent with the theory that girls show a greater relational orientation than boys, and that disruptions or threats to their interpersonal relations are more harmful for them compared to boys (Leadbeater et al. 1995, 2006; Nolen-Hoeksema 2006; Rudolph et al. 2000; Rudolph and Hammen 1999). Indeed, research with children shows that girls feel more emotionally distressed by peers’ relationally aggressive acts than boys do (Crick 1995).

Interpersonal Resources: The Protective Effects of Emotional Support on Depressive Symptoms

Although popular views often portray adolescent-parent relationships as conflictual, research supports their continued importance throughout adolescence (Collins and Laursen 2004). Family relations remain the primary context for social influence and security, and most adolescents report closeness with their parents (Meece and Laird 2006; Peterson 2005). At the same time, relationships with peers become increasingly important in early adolescence and are characterized by higher levels of self-disclosure, intimacy, and support than in childhood (Meece and Laird 2006). Thus, parents and peers are no longer viewed as competing sources of influence. Research is needed to better understand how these two types of relationships function together to enhance or disrupt the lives of adolescents (Collins and Laursen 2004).

Emotional support, or “the extent to which personal relationships are perceived as close, confiding, and satisfying” (Slavin and Rainer 1990, p. 409), is one element of social support. Emotional support is strongly linked to psychological outcomes and is salient in response to a wide variety of stresses (Cohen and Wills 1985; House et al. 1985). Parental and peer emotional support predict decreases in depressive symptoms in adolescents both concurrently and longitudinally, with some studies suggesting that support may differentially affect male and female adolescents’ psychological health (e.g., Helsen et al. 2000; Schraedley et al. 1999) but not others (e.g., Barrera and Garrison-Jones 1992; Colarossi and Eccles 2003; Cumsille and Epstein 1994). Further, the protective capacity of emotional support depends on who provides the support to youth. For example, Newcomb (1990) found that parental support predicted fewer future depressive symptoms for girls but not boys, whereas peer support predicted fewer depressive symptoms for boys but not girls. In contrast, Slavin and Rainer (1990) reported that peer support predicted decreases in depressive symptoms only in girls, and Stice et al. (2004) found that low peer support failed to predict increases in future depressive symptoms. Thus, while emotional support generally predicts fewer depressive symptoms in adolescence, these effects may be moderated by sex and source of emotional support.

Helsen et al. (2000) found that the effect of peer support on depressive symptoms was moderated by levels of (aggregated) parental support in a sample of 12–24 year-olds. In the context of high parental support, those who reported high levels of peer support showed slightly fewer emotional problems than those who reported low levels of peer support. In the context of low parental support, however, youth who reported high levels of peer support showed greater emotional problems than those who reported low levels of friends’ support. Young et al. (2005) found a similar moderation effect. Although findings linking peer emotional support to depressive symptoms are inconsistent, peers play an increasingly central role in the lives of adolescents and the influence of the support they provide needs to be better understood.

Additional research is also needed to understand the unique effects of emotional support from mothers and—in particular—fathers in adolescence. Whereas past research has often aggregated measures of maternal and paternal variables, recent findings suggest that their influences should be assessed separately. In a prospective study, Colarossi and Eccles (2003) found that high maternal and peer emotional support predicted decreases in boys’ and girls’ levels of depressive symptoms 1 year later, which is consistent with considerable research showing that maternal support is negatively related to emotional problems during adolescence (e.g., Carbonell et al. 1998; Helsen et al. 2000; Stice et al. 2004; Leadbeater et al. 1999). However, perceived levels of paternal support were lower than maternal support in Colarossi and Eccles’s study, particularly for females, and paternal emotional support was not a significant predictor of adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Furthermore, a relative lack of research into paternal influences compared to mothers (and peers) has been documented, implying an obvious need to increase investigation into the unique role that fathers play in their children’s development and well-being (Phares et al. 2005).

Bridging the Gap Between Interpersonal Risks and Resources

Relational victimization presents an interpersonal risk for depressive symptoms in adolescence, whereas emotional support presents an interpersonal resource that protects against depressive symptoms in adolescence. Research is needed to investigate whether emotional support protects against the development of depressive symptoms in the context of relational victimization. Some research has begun to investigate the protective effects of supportive social networks for victimized adolescents. Specifically, Yeung and Leadbeater (2010) examined the moderating effects of emotional support from parents and teachers on the relationships between physical and relational victimization and broad emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents across two waves of data separated by 2 years. Higher levels of teacher and paternal support predicted lower levels of concurrent and future emotional and behavioral problems, whereas higher levels of maternal emotional support predicted lower concurrent emotional problems. Only teacher support moderated the effects of relational victimization on emotional and behavioral problems across time. We extend these findings by focusing specifically on depressive symptoms and on emotional support differences that reflect the changing roles of parents and peers in adolescence and the transition to young adulthood (i.e., across ages 12–24). Additionally, this study accounts for the contribution of youths’ own levels of aggression to their peer victimization and depressive symptoms (Baldry 2004; Leadbeater et al. 2006; Seals and Young 2003).

The Current Study

The current study investigates the protective effects of emotional support from three different support providers (i.e., mothers, fathers, and peers) on depressive symptoms concurrently and across time in a large sample of adolescents. Further, we assess whether emotional support from these providers buffers depressive symptoms in the context of one particularly problematic interpersonal stressor—namely, relational victimization by peers (while controlling for adolescents’ own levels of aggression).

Ample research supports the conclusion that having a best friend is protective for children who are victimized by peers (e.g., Cowie 2000; Crick and Grotpeter 1996; Hodges et al. 1999). However, little is known about the protective effects of social networks for victimized adolescents. Research is needed to better understand relational victimization in age periods other than middle childhood (Crick et al. 2001). The present study contributes to the peer victimization literature by studying relational victimization and depressive symptoms in a large, random sample of youth ranging from early to late adolescence.

Based on the peer victimization literature reviewed, we first hypothesize that relational victimization predicts higher levels of concurrent depressive symptoms and increases in future depressive symptoms; however, this relationship is stronger for girls than boys. Remaining hypotheses are made based on findings from the emotional support literature reviewed. Second, emotional support from mothers and peers—but not fathers—predicts lower levels of concurrent depressive symptoms and decreases in future depressive symptoms. Third, maternal and peer emotional support—but not father support—moderate the association between relational victimization and depressive symptoms, with higher levels of support predicting fewer concurrent depressive symptoms and decreases in future depressive symptoms. Fourth, maternal—but not paternal—and peer emotional support will together moderate the association between relational victimization and depressive symptoms: In the context of high levels of maternal emotional support, high levels of peer emotional support will predict fewer concurrent depressive symptoms and decreases in future depressive symptoms; conversely, in the context of low levels of maternal emotional support, high levels of peer emotional support will predict higher concurrent depressive symptoms and increases in future depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants

Participants completed the “Victoria Healthy Youth Survey” questionnaire in the spring of 2003 (T1) in a medium-sized Canadian city. The same questionnaire was completed again in the spring of 2005 (T2) and spring of 2007 (T3). The University of Victoria’s Human Research Ethics Board approved the research. We phoned households from a random sample of 9,500 telephone listings to identify eligible youth between ages 12 and 19. One thousand thirty-six households contained at least one youth who met the criteria. Of these, 187 youth refused participation and 185 parents or guardians refused their youth’s participation. At T1, data were available from 664 adolescents (321 boys and 343 girls; M = 15.5 years, SD = 1.9 years). The ethnic makeup of participants was 85% European-Canadian, 4% Asian or Asian-Canadian, 3% Aboriginal, and 8% other ethnicities. At T2, the attrition rate was 12.7% (n = 84), including 29 youths who actively declined participation, 46 youths who could not be located or did not respond, and 8 youths who did not participate for unknown reasons. In addition, data for one youth were unusable due to interviewer discomfort and termination of the interview. Data were available from 580 adolescents (273 boys and 307 girls; M = 17.6 years, SD = 1.9 years). At T3 (2007), the sample further decreased by 7.9% (n = 40), including 7 youths who actively declined participation, 29 who could not be located or did not reply, and 4 for unknown reasons. Data were available from 540 adolescents (246 boys and 294 girls; M = 19.5 years, SD = 1.9 years). Investigation of systematic attrition using ANOVA did not reveal any differences on measured variables at T1 between participants who dropped out by T3 and those who remained in the study.

Demographic information for adolescents’ living situation and socioeconomic status was gathered from adolescents at T1. Reports indicated that 68.1% of adolescents lived in a two-parent household, 20.2% lived with their mother only, 7.6% lived back and forth between their mother’s and father’s households, 2.1% lived with their father only, and 2% had other arrangements (e.g., lived with siblings or grandparents). Most adolescents came from middle class families, with 83.3% of adolescents reporting that their families never experienced financial difficulties, 13.4% reporting that their families sometimes experienced financial difficulties, and 3% reporting that their families often faced financial problems. Eight percent of adolescents indicated that their family had previously received welfare assistance.

Procedure

Adolescents were administered the survey by trained interviewers who met with them individually, either in their home or a quiet location of their choice. For the measures of peer victimization, aggression, parental emotional support and peer emotional support, interviewers read questions aloud to participants and recorded their responses. For the measure of depressive symptoms, interviewers similarly read the questions aloud; however, adolescents recorded their own answers. The survey took approximately 1 h to complete and participants received a $25.00 gift certificate as remuneration. The same procedure was employed at T2 and T3.

Measures

Cronbach’s alphas (α) for the study’s main measures at each time point are provided in Table 1. Internal reliabilities were all acceptable, ranging from adequate to good.

Table 1.

Cronbach’s alphas, mean levels and standard deviations of variables for boys and girls and young-mid and mid-late adolescents

| Variables | α | Boys | Girls | Sex group difference | Young-mid adolescents | Mid-late adolescents | Age group difference | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Sx | ||||||||

| T1 | .74 | 1.38 (0.36) | 2.80 (0.30) | ** | 1.39 (0.38) | 1.48 (0.41) | ** | 1.44 (0.40) |

| T2 | .76 | 1.47 (0.41) | 1.54 (0.41) | * | 1.43 (0.40) | 1.52 (0.41) | * | 1.50 (0.41) |

| T3 | .78 | 1.57 (0.42) | 1.58 (0.42) | a | a | a | 1.58 (0.42) | |

| RV | ||||||||

| T1 | .73 | 1.17 (0.28) | 1.22 (0.31) | * | 1.24 (0.34) | 1.16 (0.26) | ** | 1.20 (0.30) |

| T2 | .72 | 1.12 (0.23) | 1.16 (0.27) | 1.20 (0.33) | 1.13 (0.23) | * | 1.14 (0.25) | |

| T3 | .71 | 1.15 (0.24) | 1.21 (0.29) | * | a | a | a | 1.18 (0.27) |

| Maternal ES | ||||||||

| T1 | .75 | 2.80 (0.30) | 2.79 (0.32) | 2.84 (0.27) | 2.76 (0.34) | ** | 2.80 (0.31) | |

| T2 | .76 | 2.71 (0.36) | 2.78 (0.33) | * | 2.77 (0.34) | 2.74 (0.35) | 2.75 (0.35) | |

| T3 | .73 | 2.74 (0.32) | 2.79 (0.34) | a | a | a | 2.77 (0.33) | |

| Paternal ES | ||||||||

| T1 | .77 | 2.65 (0.37) | 2.57 (0.46) | * | 2.68 (0.38) | 2.55 (0.45) | ** | 2.61 (0.42) |

| T2 | .79 | 2.57 (0.38) | 2.51 (0.50) | 2.63 (0.42) | 2.52 (0.45) | * | 2.54 (0.45) | |

| T3 | .83 | 2.60 (0.41) | 2.55 (0.52) | a | a | a | 2.57 (0.47) | |

| Peer ES | ||||||||

| T1 | .67 | 0.73 (0.21) | 0.85 (0.18) | ** | 0.77 (0.22) | 0.81 (0.19) | 0.80 (0.20) | |

| T2 | .66 | 0.75 (0.20) | 0.88 (0.16) | ** | 0.79 (0.22) | 0.83 (0.18) | 0.82 (0.18) | |

| T3 | .70 | 0.85 (0.18) | 0.92 (0.14) | ** | a | a | a | 0.89 (0.16) |

Sx Symptoms, RV relational victimization, ES emotional support. Young-mid adolescents = 12–15.5 years, mid-late adolescents = 15.5–21 years

p < .05,

p <.01

At T3, all participants were in the mid-late adolescence age group

Relational Victimization

Self-reported experiences of peer victimization were measured using the Social Experience Questionnaire (SEQ; Crick and Grotpeter 1996). Participants rated five items that assess the frequency of relational victimization (e.g., “How often do your peers tell lies about you to make others not like you anymore?”) on a 3-point scale (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = almost all the time). For the regression analyses, total scale scores were computed by summing each participant’s scores for the items within each scale (range = 5–15).

Depressive Symptoms

Adolescents’ depressive symptoms were assessed using five items from the adolescent self-report form of the Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (BCFPI; Cunningham et al. 2007). Participants rated the frequency of their depressive symptoms (e.g., “How often do you notice that you feel hopeless?”) on a 3-point scale (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often). Total scores ranged from 5 to 15.

Parental Emotional Support

Participants were asked to answer parental support items with reference to the individuals they most consider their “mother” and “father,” such as biological, adoptive, step, foster, or other parental figures. At each time point, the majority of adolescents rated emotional support received from biological mothers (97%) and biological fathers (88% at T1, 91% at T2, and 90% at T3). Levels of parental emotional support were assessed using the Child’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI; Schaefer 1965). On a three-point scale (1 = not like him/her, 2 = somewhat like him/her, 3 = like him/her), adolescents rated how much support they receive from their mother and father figures separately using five items (e.g., “My mother/father is a person who is able to make me feel better when I am upset”). Total scores for both maternal and paternal emotional support ranged from 5 to 15.

Peer Emotional Support

Adolescents indicated how much emotional support they receive from their peers on items from the Perceived Social Support From Friends scale (PSS-Fr; Procidano and Heller 1983). The nine peer support items (e.g., “I rely on my friends/peers for emotional support”) were coded on a 2-point scale (0 = don’t know/no, 1 = yes). Total scores ranged from 0 to 9.

Physical Victimization

Consistent with past research investigating the unique effects of relational victimization (e.g., Crick and Grotpeter 1996; Crick and Bigbee 1998; Baldry 2004; Prinstein et al. 2001; Vuijk et al. 2007), adolescents’ experiences of physical victimization were controlled for in the current study. Participants rated their experiences of physical victimization on five items (e.g., “How often do you get pushed or shoved by your peers?”) on a 3-point scale (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = almost all the time) taken from the SEQ (Crick and Grotpeter 1996). Total scores ranged from 5 to 15. Internal consistency (α) was .67 at T1, .63 at T2, and .68 at T3.

Physical and Relational Aggression

Findings have linked aggressive bullying behaviors with depressive symptoms (e.g., Baldry 2004; Leadbeater et al. 2006; Seals and Young 2003), and significant correlations between these measures were observed in the current sample. Consequently, adolescents’ physical and relational aggression (measured using the Children’s Peer Relations Scale; Crick and Grotpeter 1995) were controlled. Adolescents rated their own levels of physical aggression (e.g., “Some teens hit others. How often do you do this?”) on three items and relational aggression (e.g., “Some teens tell lies about someone so that the others won’t like them anymore. How often do you do this?”) on five items, both using a 5-point scale (1 = never, 2 = almost never, 3= sometimes, 4 = almost all the time, 5 = all the time). Total scores ranged from 3 to 15 for physical aggression and from 5 to 25 for relational aggression. Internal consistency was .75 at T1, .72 at T2, and .82 at T3 for physical aggression. Alpha was .76 at T1, .79 at T2, and .71 at T3 for relational aggression.

Parental Psychological Control

Psychological control refers to parents’ attempts to control their adolescent using strategies such as guilt induction, love withdrawal, ignoring or shaming, and is a well-established contributor to depressive symptoms in adolescents (see Barber and Harmon 2002). Furthermore, as expected, parental psychological control was negatively correlated with emotional support from maternal and paternal emotional support providers in this sample. To evaluate the effects of parental emotional support independently from parental psychological control, the latter (measured using the Psychological Control Scale Youth Self-Report; Barber 1996) was controlled for. Participants rated parents’ levels of psychological control on eight items (e.g., “My mom/dad is always trying to change how I feel or think about things”) using a 3-point scale (1 = not like him/her, 2 = somewhat like him/her, 3 = like him/her). Total scores ranged from 8 to 24. Internal consistency was .75 at T1, .72 at T2, and .78 at T3 for ratings of maternal psychological control. Alpha was .76 at T1, .79 at T2, and .77 at T3 for ratings of paternal psychological control. Measures of socioeconomic status were not significantly correlated with any of the study’s main variables.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations, along with sex- and age-group differences, are presented in Table 1. Girls reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than boys at T1 and T2, but not at T3. Girls also reported higher levels of relational victimization at T1 and T3. Girls consistently reported higher levels of peer emotional support than boys. Sex differences in maternal and paternal emotional support were less consistent. Significant differences between younger (i.e., below 15.5 years) and older (i.e., 15.5 years and older) also occurred, with the latter endorsing greater depressive symptoms. Younger adolescents consistently reported higher levels of both relational victimization and paternal emotional support compared to older adolescents. Younger adolescents also reported higher levels of maternal emotional support, but only at T1. Pearson’s correlations between variables concurrently and across time are shown in Table 2. Correlations reveal moderate stability among the variables over time. Correlations between relational victimization and depressive symptoms ranged from .17 to .39, and correlations were slight between relational victimization and maternal (range = −.06 to −.19), paternal (range = −.03 to −.14), and peer (range = −.03 to −.24) emotional support.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations of variables at T1, T2, and T3

| Variable | 1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| Depressive Sx | |||||||||||||||

| T1 | – | ||||||||||||||

| T2 | .56** | – | |||||||||||||

| T3 | .44** | .48** | – | ||||||||||||

| RV | |||||||||||||||

| T1 | .33** | .20** | .20** | – | |||||||||||

| T2 | .26** | .27** | .17** | –.43** | – | ||||||||||

| T3 | .21** | .39** | .32** | .29** | .39** | – | |||||||||

| Maternal ES | |||||||||||||||

| T1 | −.28** | −.24** | −.22** | −.06 | −.13** | −.08 | – | ||||||||

| T2 | −.21** | −.31** | −.49** | −.07 | −.19** | −.13** | .47** | – | |||||||

| T3 | −.13** | −.17** | −.21** | −.10* | −.14** | −.18** | .31** | .49** | – | ||||||

| Paternal ES | |||||||||||||||

| T1 | −.26** | −.18** | −.19** | −.10 | −.07 | −.11** | .24** | .10* | .10* | – | |||||

| T2 | −.13** | −.17** | −.15** | −.05 | −.11** | −.14** | .09* | .17** | .14** | .57** | – | ||||

| T3 | −.11* | −.13** | −.16** | −.03 | −.13** | −.13** | .10* | .13** | .20** | .44** | .61** | – | |||

| Peer ES | |||||||||||||||

| T1 | −.19** | −.20** | −.16** | −.24** | −.14** | −.06 | .19** | .15** | .13** | .15** | .08 | .03 | – | ||

| T2 | −.18** | −.23** | −.14** | −.10* | −.17** | −.03 | .11** | .18** | .14** | .10* | .07 | .07 | .49** | – | |

| T3 | −.17** | −.12* | −.18** | −.17** | −.17** | −.10** | .09 | .13** | .18** | .08 | .08 | .11* | .38** | .50** | – |

Sx Symptoms, RV relational victimization, ES emotional support

p < .05,

p <.01

Relational Victimization

To examine relational victimization levels in this sample, participants with scores one standard deviation above the sample mean were considered victimized (following Crick and Grotpeter 1996). At T1, 13.3% (n = 88) of participants were identified as relationally victimized by their peers. Victim status significantly differed by both age group, F (1, 656) = 4.72, p < .05, and sex, F (1, 656) = 6.90, p < .01. Younger adolescents (n = 53) and girls (n = 55) were more likely to be classified as victims than older adolescents (n = 35) and boys (n = 33). At T2, 18.4% (n = 107) and at T3, 13.5% (n = 73) of participants were classified as victims of peer relational aggression. Victimization classifications did not significantly differ by sex or age group at T2 and T3.

Effects of Relational Victimization, Emotional Support, and their Interactions on Depressive Symptoms

We followed well-established and commonly used guidelines for examining moderation using multiple linear regression (Aiken and West 1991; Baron and Kenny 1986). This data analytic strategy provided a more direct, accessible, and easily interpretable way of examining our main hypotheses compared to other approaches (e.g., structural equation modeling; see Tomarken and Waller 2005). Multiple linear regression was used to examine predictors of depressive symptoms both concurrently and across time. Independent (i.e., relational victimization) and moderator (i.e., maternal, paternal, and peer emotional support) variables were centered to reduce multicollinearity (Aiken and West 1991; Baron and Kenny 1986). In all analyses, sex, age, aggression against peers, parental psychological control, and physical victimization were controlled. Direct effects of independent and moderator variables, along with the hypothesized interactions, were all entered in the same step. Interaction terms for maternal, paternal, and peer variables were analyzed separately to assess for potential suppressor effects; however, results were consistent with those obtained with all variables entered in the same step. Significant interactions were probed according to procedures outlined by Aiken and West (1991).

Concurrent Relations

Concurrent results for T1, T2, and T3 are shown in Table 3. At each time point, relational victimization significantly predicted adolescents’ depressive symptoms, with higher levels of victimization predicting greater symptoms. Direct effects of both maternal and peer emotional support on adolescents’ depressive symptoms were also significant, with higher levels of emotional support from mothers and peers consistently predicting fewer depressive symptoms. Effects of paternal emotional support on depressive symptoms were not significant.

Table 3.

Concurrent regression analyses

| Variables | T1 Depressive symptoms (B) | T2 Depressive symptoms (B) | T3 Depressive symptoms (B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | |||

| Sex (1 = male, 2 = female) | .65** | .66** | .36 |

| Age | .01** | .02** | .01** |

| Aggression | .07** | .09** | .11** |

| Parental psychological control | .07** | .09** | .01 |

| Physical victimization | .15** | .07 | .28** |

| Direct effects | |||

| RV | .38** | .28** | .39** |

| Maternal ES | −.26** | −.39** | −.22* |

| Paternal ES | −.12 | −.15 | −.13 |

| Peer ES | −.18* | −.43** | −.32** |

| Interactions | |||

| RV × maternal ES | −.06 | −.04 | −.03 |

| RV × paternal ES | −.01 | .04 | .02 |

| RV × peer ES | −.03 | .03 | −.13 |

| Adjusted R2 | .28 | .23 | .21 |

| F | 20.60** | 14.64** | 9.73** |

| df | 607 | 543 | 385 |

RV Relational victimization, ES emotional support

p < .05,

p <.01

Interactions between relational victimization and sex were also not significant. Because sex did not moderate the relationship between relational victimization and depressive symptoms in any analysis (i.e., neither concurrently nor longitudinally), it was not tested in the final models to increase power. Interactions between emotional support from the three providers and relational victimization were not significant concurrently. Finally, three-way interactions between relational victimization, maternal/paternal emotional support, and peer emotional support were all not significant and were also dropped from the final models.

Longitudinal Relations

Longitudinal results are shown in Table 4. After accounting for control variables and prior depressive symptoms, relational victimization did not predict further changes in adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Emotional support from mothers, fathers, and peers were not directly associated with adolescents’ depressive symptoms longitudinally.

Table 4.

Longitudinal regression analysis

| Variables | Variables predicting T3 depressive symptoms (B) |

|---|---|

| T1 controls | |

| Sex (1 = male, 2 = female) | −.13 |

| Age | .08 |

| Aggression | −.03 |

| Parental psychological control | −.01 |

| Physical victimization | .05 |

| Depressive symptoms | .20** |

| T2 controls | |

| Age | −.08 |

| Aggression | .00 |

| Parental psychological control | .02 |

| Physical victimization | .12 |

| Depressive symptoms | .37** |

| T1 direct effects | |

| RV | .14 |

| Maternal ES | .17 |

| Paternal ES | −.07 |

| Peer ES | −.11 |

| T2 direct effects | |

| RV | .02 |

| Maternal ES | .00 |

| Paternal ES | −.07 |

| Peer ES | .11 |

| T1 interactions | |

| RV × maternal ES | −.05 |

| RV × paternal ES | −.00 |

| RV × peer ES | .08 |

| T2 interactions | |

| RV × maternal ES | .25** |

| RV × paternal ES | −.28** |

| RV × peer ES | .13* |

| R2 | .33 |

| F | 8.95** |

| df | 463 |

RV Relational victimization, ES emotional support

p < .05,

p <.05

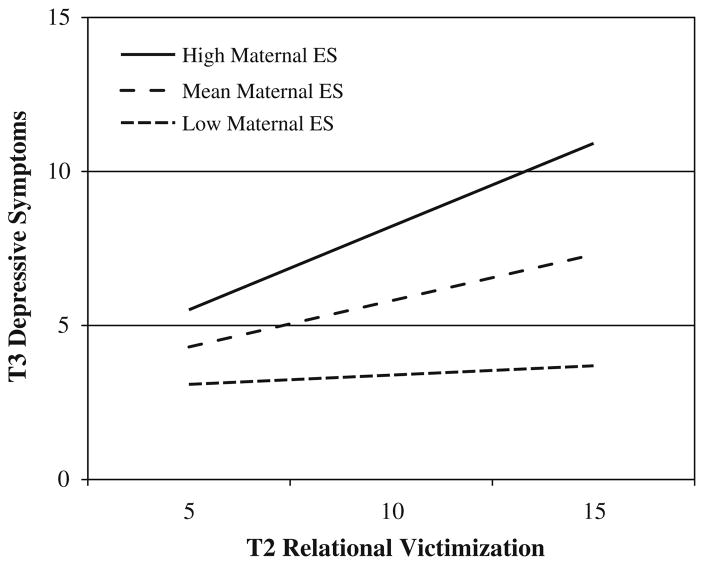

However, three interactions between relational victimization and emotional support were observed longitudinally. First, a significant interaction between T2 relational victimization and T2 maternal emotional support predicted adolescents’ depressive symptoms at T3 (see Fig. 1). The slope was significantly different from zero at both high, b = 0.54, SE = .14, t(464) = 3.8, and mean levels of maternal emotional support, b = 0.3, SE = .01, t(464) = 3.0, but not at low levels of maternal emotional support, b = 0.06, SE = .14, t(464) = 0.42. Thus, relationally victimized adolescents with high levels of maternal emotional support experienced increases in depressive symptoms, whereas those who reported mean or low levels of maternal emotional support did not.

Fig. 1.

The moderating effect of T2 maternal emotional support on the association between T2 relational victimization and T3 depressive symptoms. Note: ES = Emotional support

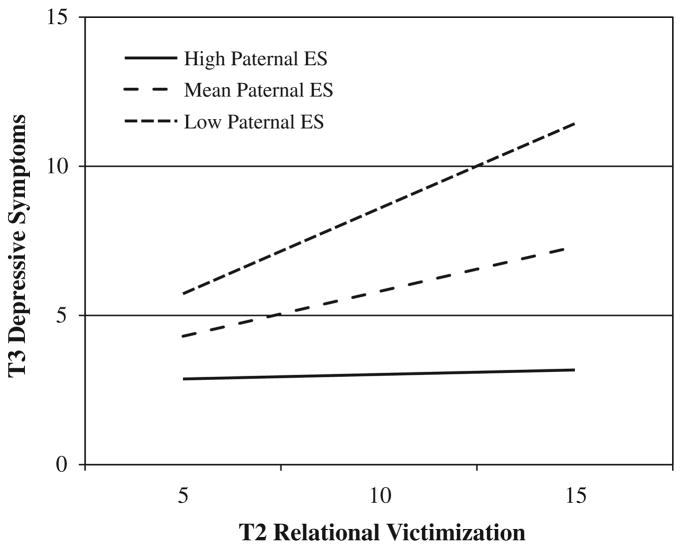

Second, T2 relational victimization interacted with T2 paternal emotional support to predict adolescents’ depressive symptoms at T3 (see Fig. 2). The slope was significantly different from zero at low, b = 0.57, SE = .11, t(464) = 4.03, and at mean levels of paternal emotional support, b = 0.30, SE = .01, t(464) = 3.0, but not at high levels of paternal emotional support, b = 0.03, SE = .14, t(464) = 0.21. Thus, relationally victimized adolescents who reported low or average levels of paternal emotional support experienced increases in depressive symptoms, whereas those who reported high levels of paternal emotional support did not.

Fig. 2.

The moderating effect of T2 paternal emotional support on the association between T2 relational victimization and T3 depressive symptoms. Note: ES = Emotional support

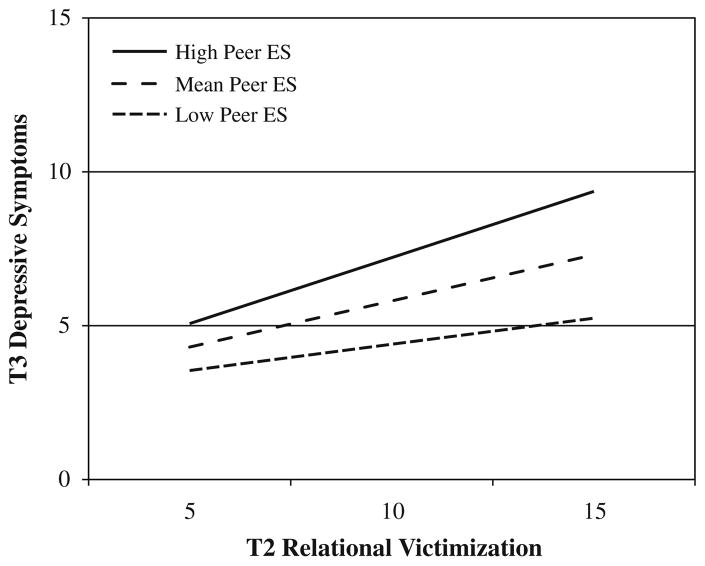

Finally, a significant interaction between T2 relational victimization and T2 peer emotional support predicted adolescents’ depressive symptoms at T3 (see Fig. 3). Simple slope analysis revealed that the slope was significantly different from zero both at high, b = 0.43, SE = .01, t(464) = 4.3, and at mean levels of peer emotional support, b = 0.30, SE = .01, t(464) = 3.0, but not at low levels of peer emotional support, b = 0.17, SE = .01, t(464) = 1.7. Thus, relationally victimized adolescents who reported high levels of emotional support from peers were more likely to experience increases in depressive symptoms compared to those who reported low levels of peer emotional support.

Fig. 3.

The moderating effect of T2 peer emotional support on the association between T2 relational victimization and T3 depressive symptoms. Note: ES = Emotional support

Discussion

Past research shows that relational victimization by peers portends increased vulnerability to depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence. Although a large body of literature suggests that emotional support buffers depressive symptoms generally, less is known about the effects of emotional support for adolescents who are relationally victimized. This study bridges these domains by examining the moderating effects of maternal, paternal, and peer emotional support on the relationship between relational peer victimization and depressive symptoms in a large sample of adolescents. Across three waves of data separated by 2 years, 13–18% of adolescents were relationally victimized by their peers. This figure falls within the range of victimization generally found in research with community-based samples (i.e., 10–30%, Hawker and Boulton 2000), but is somewhat lower than rates of relational victimization reported in studies with younger adolescents (e.g., 51%, Bond et al. 2001; 33%, Vuijk et al. 2007). Lower rates of relational victimization likely reflect the older age of participants in our sample compared to most published work. We also used more conservative classification criteria than Bond et al., who required participants to answer “yes” to one (or more) of four dichotomous victimization items. We required participants to report victimization levels one standard deviation above the mean (following Crick and Grotpeter 1996). Our finding that younger adolescents reported greater relational victimization than older adolescents shows that relational victimization declines with age, but can still pose a problem for older youth. New interpersonal contexts in late adolescence and early adulthood such as co-habitation with roommates, socializing with co-workers or classmates, participation in romantic relationships, and the dynamics of personal peer groups may provide opportunities for the occurrence of relational victimization in this age group that are not easy to leave behind.

Relational victimization was consistently and uniquely associated with concurrent depressive symptoms, but did not predict further increases in adolescents’ depressive symptoms over time. It is possible that changing peer networks of youth in the transition to young adulthood have some protective effects that reduce the chronicity of relational victimization over time. However, the contribution of relational victimization to concurrent symptoms is substantial. Given that depression is typically episodic in nature, relational victimization may act as a trigger for depressive episodes.

Past research with adolescents has found a stronger relationship between relational victimization and depressive symptoms in girls than boys (Baldry 2004; Prinstein et al. 2001; Storch et al. 2003; Vuijk et al. 2007). In the current study, sex did not moderate this relationship, suggesting that the harmful effects of relational victimization are not exclusive to girls in the transition to young adulthood. Consistent with past findings (Colarossi and Eccles 2003; Newcomb 1990; Slavin and Rainer 1990), peer and maternal emotional support—but not father support—had direct negative effects on adolescents’ concurrent depressive symptoms.

Longitudinally, peer emotional support moderated the association between relational victimization and depressive symptoms. However, contrary to our hypotheses, adolescents who were relationally victimized and reported high or mean levels of emotional support from peers showed increases in depressive symptoms, whereas relationally victimized adolescents with low levels of peer emotional support did not. Youth who report receiving emotional support from peers may co-ruminate with peers without seeking real solutions to their problems. Co-rumination includes excessive and repeated discussion and speculation about problems that focus on negative feelings (Rose 2002). In the context of relational victimization, co-rumination might involve adolescents talking at length about victimization experiences or reasons why the victim was targeted. While co-rumination can involve elements of high-quality peer relationships such as self-disclosure and sharing personal thoughts and feelings, it can also involve a social form of rumination that has been linked to depressive symptoms in adolescence (Rose 2002). More generally, peer emotional support may be of a relatively poor quality and may sometimes reflect undeveloped, undesirable values (e.g., promoting retaliation for being victimized), which may exacerbate the depressive symptoms. Emotional support from peers may also be unstable over time as adolescents’ social networks and best friends change rapidly as these youth change work and school contexts (Stice et al. 2004). We also suspected that some youth who report high levels of emotional support from peers may have less contact with their parents or other sources of adult support; however, post-hoc analyses did not support this conclusion. Finally, self-disclosure made in the context of emotionally-supportive exchanges may provide fuel for relational victimization. These unexpected findings highlight the complexity that emerges when we move beyond direct effects to examine interactions between variables over time. They also highlight the need for research examining the effects of different types and qualities of peer support in the transition to young adulthood.

Findings for the moderating effects of maternal emotional support followed a similar pattern to that of peers: Contrary to expectation, relationally victimized adolescents who reported high or mean levels of emotional support from mothers reported increases in depressive symptoms in the transition to young adulthood, whereas relationally victimized youth with low levels of maternal emotional support did not. Although rates are lower than with peers, research shows that some older adolescents and young adults engage in co-rumination with their mothers (Calmes and Roberts 2008) and that doing so relates to their internalizing symptoms (Waller and Rose 2010). Consistent with this hypothesis, other research shows that adolescents are more likely to self-disclose personal matters to mothers than fathers (Smetana et al. 2006). Still, research investigating mother-adolescent co-rumination is limited to only two cross-sectional studies, and additional research is needed to explain the longitudinal effects in this study. Other research with adolescent mothers transitioning to adulthood found that emotional support was related to poor school achievement, whereas conditional support (support provided in the context of clear expectations and demands) was characteristic of young women who were most resilient to negative developmental outcomes (Way and Lead-beater 1999; Leadbeater and Way 2001).

Surprisingly, only emotional support received from fathers buffered the depressive symptoms associated with relational victimization over time. The protective effects of paternal emotional support may increase as youth prepare for the challenges associated with young adulthood. It is not known how emotional support from fathers differs from that of mothers. Fathers may be less empathic and provide more emotional coping strategies that are particularly effective during this transition—namely, active problem-solving. In the context of relational victimization, fathers’ support may go beyond attempts to empathize with or reduce emotional distress and support efforts to end negative relationships (Yeung and Leadbeater 2010). Active approaches to regulating emotions and stopping victimization may be more supportive of youths’ competence as societal demands for their autonomy are rising (e.g., education/employment, independent living). In addition, assessing emotional support only may have actually underestimated the influence of fathers on adolescents’ depressive symptoms in this study. Future research is needed to examine the effects of different types and expressions of paternal support (e.g., informational, material, consultative).

Ratings of paternal emotional support were consistently lower than ratings for mothers and peers, which replicates past findings (Colarossi and Eccles 2003). Thus, it may be unusual for adolescents to receive particularly high levels of emotional support from fathers and benefit from the more moderate or low levels provided. Grossmann et al. (2002) found that fathers’ support for their young children’s exploration made a larger unique contribution to children’s emotional security at age 16 than did mothers’ support of exploration. In a study by Day and Padilla-Walker (2009), father—but not mother—connectedness and involvement were associated with fewer depressive symptoms in early adolescents. Other research has shown that fathers’ involvement with adolescents predicts lower levels of youths’ externalizing behaviors, whereas the same variables for mothers do not (Williams and Kelly 2005). Finally, Videon (2005) found that youth who perceived their relationship with their father as satisfying reported significantly fewer depressive symptoms than those who rated their relationships as unsatisfying both concurrently and longitudinally, over and above the effects of mother-adolescent relations.

Together, results from the present study suggest that emotional support from fathers is particularly important for relationally victimized adolescents, whereas mother or peer emotional support may have problematic qualities during the transition from late adolescence to young adulthood. It is possible that, in response to victimized adolescents’ elicitation of support, mothers and peers may provide emotion-focused support that offers empathy and understanding, which affirm adolescents’ depressive symptoms. In contrast, father’s emotional support may be provided within a larger context focused on addressing adolescents’ problems. Qualitative research is needed to disentangle the forms and functions of emotional support parents and peers offer to relationally victimized adolescents and young adults to inform appropriate interventions. At present, however, father figures should be aware that emotional support towards adolescents is consequential and can buffer the mental health outcomes associated with relational victimization.

This study has some limitations that could be addressed in future research. First, another central source of adolescents’ emotional support was not examined—that is, support provided by romantic relationship partners (Furman and Buhrmester 1992). It is likely that several adolescents were involved in romantic relationships, and consideration of romantic partners’ provision of emotional support may have helped explain some of our findings. Future research should investigate moderating effects of this potential source of support. Another limitation is that all data were adolescent self-reports. As such, mono-method variance may have enhanced the associations between victimization, depressive symptoms, and emotional support. Negative cognitive biases may lead adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms to report more relational victimization experiences or less emotional support from others. Conversely, adolescents who perceive themselves as victimized may be more likely to perceive themselves as depressed. Future research should consider using multi-informant approaches (e.g., parental ratings of symptoms, teacher or peer nominations of victimization). Another consideration is that emotional support was measured in general, rather than as a specific response to victimization experiences. Research into the emotional support adolescents receive in relation to their victimization experiences in particular, as well as the strategies that mothers, fathers, and peers employ in response to adolescents’ victimization experiences, is needed to identify potential strategies for maximizing the positive effects of emotional support for relationally victimized youth. When surrounded by supportive contexts that are responsive to victims’ emotional needs, greater buffering effects may be observed. Finally, future research should consider using more advanced statistical procedures, such as multi-level modeling, to replicate or expand on these findings.

Findings support a growing literature suggesting that relational victimization is a hurtful experience that presents a clear risk for the development or exacerbation of depressive symptoms well into adolescence and young adulthood. They also reveal salient interpersonal processes that influence the course of depressive symptoms in adolescents who experience relational victimization by peers. Importantly, emotional support may serve either a protective or vulnerability-enhancing role for relationally victimized youth depending on who provides this support. High levels of emotional support received from fathers buffers the depressive symptoms associated with relational victimization over time, whereas emotional support from mothers and peers may increase victimized adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Greater understanding of the helpful and unhelpful qualities of emotional support provided in the context of peer victimization is needed to inform approaches that others should emphasize or avoid when providing support to victimized adolescents and young adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the youth who participated in this study and the researchers and research assistants affiliated with the Centre for Youth and Society at the University of Victoria. We also thank Marsha Runtz, Erica Woodin, and Joan Martin for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of the paper. This research was supported by grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research to the first author, and by a Community Alliance for Health Research grant from Canadian Institutes of Health Research to the second author.

Biographies

Tracy L. Desjardins is a Doctoral student in Clinical Psychology at the University of Victoria, Canada. She received her MSc in Clinical Psychology from the University of Victoria. Her research interests include mental health and social relationships in childhood and adolescence, with a major focus on peer victimization and aggression across these developmental periods.

Bonnie J. Leadbeater, PhD (Columbia) is a Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Victoria. Her research focuses on mental health of children and adolescence, resilience in the transition to young adulthood for high-risk youth, and the role of peer victimization in the development of depression and problem behaviors.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. London, England: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baldry AC. Mental and physical health of Italian youngsters directly and indirectly victimized at school and home. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 2004;3:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development. 1996;67:3296–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Harmon EL. Violating the self: Parent psychological control of children and adolescents. In: Barber BK, editor. Intrusive parenting: How psychological control affects children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 15–52. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Garrison-Jones C. Family and peer social support as specific correlates of adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1992;20:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00927113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond L, Carlin JB, Thomas L, Rubin K, Patton G. Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. British Medical Journal. 2001;323:480–484. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WF. Young people in Canada: Their health and well-being. Health Canada Report 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Calmes CA, Roberts JE. Rumination in interpersonal relationships: Does co-rumination explain gender differences in emotional distress and relationship satisfaction among college students? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:577–590. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell DM, Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM. Risk and resilience in late adolescence. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 1998;15(4):251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colarossi LG, Eccles JS. Differential effects of support providers on adolescents’ mental health. Social Work Research. 2003;27:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Collins W, Laursen B. Parent-adolescent relationships and influences. In: Collins W, Laursen B, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie H. Bystanding or standing by: Gender issues in coping with bullying in English schools. Aggressive Behavior. 2000;26:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Craig WM. The relationship among bullying, victimization, depression, anxiety, and aggression in elementary school children. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;24(1):123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. Relational aggression: The role of intent attributions, feelings of distress, and provocation type. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA. Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multiinformant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(2):337–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, Ku HC. Relational and physical forms of peer victimization in preschool. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(2):376–385. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Children’s treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development & Psychopathology. 1996;8(2):367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Nelson DA, Morales JR, Cullerton-Sen C, Casas JF, Hickman S. Relational victimization in childhood and adolescence: I hurt you through the grapevine. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. School-based peer harassment: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: Guildford Press; 2001. pp. 196–214. [Google Scholar]

- Cumsille PE, Epstein N. Family cohesion, family adaptability, social support, and adolescent depressive symptoms in outpatient clinic families. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:202–214. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Harrison R, Knight R, McHolm A, Pollard L, Ricketts P. The Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (BCFPI) in Hamilton: Intake Screening, triaging, outcome measurement, and program management. Psychology Ontario. 2007:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Day RD, Padilla-Walker LM. Mother and father connectedness and involvement during early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(6):900–904. doi: 10.1037/a0016438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Leadbeater BJ, Barker ET. Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann K, Grossmann KE, Fremmer-Bombik E, Kindler H, Scheuerer-Englisch H, Zimmermann P. The uniqueness of the child-father attachment relationship: Fathers’ sensitive and challenging play as a pivotal variable in a 16-year longitudinal study. Social Development. 2002;11(3):307–331. [Google Scholar]

- Hawker DS, Boulton MJ. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41(4):441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsen M, Vollebergh W, Meeus W. Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29(3):319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM. The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:98–101. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Kahn RL, McLeod JD, Williams D. Measures and concepts of social support. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Social support and health. New York: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Klerman GL, Weissman MN, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES. Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. New York: Basic Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Blatt SJ, Quinlan DM. Gender-linked vulnerabilities to depressive symptoms, stress, and problem behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Boone EM, Sangster NA, Mathieson LC. Sex differences in the personal costs and benefits of relational and physical aggression in high school. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Kuperminc GP, Blatt SJ, Hertzog C. A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1268–1282. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Way N. Growing up fast: Transitions to early adulthood of inner-city adolescent mothers. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Mahwah; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meece D, Laird RD. The importance of peers. In: Villarruel FA, Luster T, editors. The crisis in youth mental health: Critical issues and effective programs (vol 2): Disorders in adolescence. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(16):2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD. Social support and personal characteristics: A developmental and interactional perspective. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9:54–68. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Network. Trajectories of physical aggression from toddlerhood to middle childhood: Predictors, correlates, and outcomes. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2004:69. doi: 10.1111/j.0037-976x.2004.00312.x. serial no. 279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in depression. In: Gotleib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. New York: The Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 492–509. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school. Cambridge, UK: Blackwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson GW. Family influences on adolescent development. In: Gullotta TP, Adams GR, editors. Handbook of adolescent behavioral problems. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Fields S, Kamboukos D, Lopez E. Still looking for poppa. American Psychologist. 2005;60:735–736. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30(4):479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and family: Three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1983;11:1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ. Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development. 2002;73(6):1830–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C. Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Development. 1999;70(3):660–677. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D, Lindberg N, Herzberg D, Daley SE. Toward an interpersonal life-stress model of depression: The developmental context of stress generation. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:215–234. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer E. Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraedley PK, Gotlib IH, Hayward C. Gender differences in correlates of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25:98–108. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals D, Young J. Bullying and victimization: Prevalence and relationship to gender, grade level, ethnicity, self-esteem, and depression. Adolescence. 2003;38(152):735–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin LA, Rainer KL. Gender differences in emotional support and depressive symptoms among adolescents: A prospective analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1990;18(3):407–421. doi: 10.1007/BF00938115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Metzger A, Gettman DC, Campione-Barr N. Disclosure and secrecy in adolescent-parent relationships. Child Development. 2006;77:201–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalets MM, Luby JL. Preschool depression. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2006;15(4):899–917. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterba SK, Prinstein MJ, Cox MJ. Trajectories of internalizing problems across childhood: Heterogeneity, external validity, and gender differences. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(2):345–366. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Ragan J, Randall P. Prospective relations between social support and depression: Differential directions of effects for parent and peer support? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Phil M, Nock MK, Masia-Warner C, Barlas ME. Peer victimization and social-psychological adjustment in Hispanic and African-American children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2003;12(4):439–452. [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Waller NG. Structural equation modeling: Strengths, limitations, and misconceptions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:31–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videon TM. Parent-child relations and children’s psychological well-being: Do dads matter? Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Vuijk P, van Lier PAC, Crijnen AAM, Huizink AC. Testing sex-specific pathways from peer victimization to anxiety and depression in early adolescents through a randomized intervention trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;100:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller EM, Rose AJ. Adjustment trade-offs of co-rumination in mother-adolescent relationships. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33(3):487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way N, Leadbeater BJ. Pathways toward educational achievement among African-American and Puerto-Rican adolescent mothers: Reexamining the role of social support from families. Developmental Psychopathology. 1999;11:349–364. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, et al. Children with prepubertal-onset major depressive disorder and anxiety grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56(9):794–801. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SK, Kelly FD. Relationships among involvement, attachment, and behavioral problems in adolescence: Examining fathers’ influence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25:168–196. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung RS, Leadbeater BJ. Adults make a difference: The protective effects of parent and teacher emotional support on emotional and behavioral problems among peer victimized adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38:80–98. [Google Scholar]

- Young JF, Berenson K, Cohen P, Garcia J. The role of parent and peer support in predicting adolescent depression: A longitudinal community study. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15(4):407–442. [Google Scholar]