Abstract

Emerging research has identified sub-dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder – irritability and defiance -that differentially predict internalizing and externalizing symptoms in preschoolers, children, and adolescents. Using a theoretical approach and confirmatory factor analyses to distinguish between irritability and defiance, we investigate the associations among these dimensions and internalizing (anxiety and depression) and externalizing problems (conduct problems) within and across time in a community-based sample of 662 youth (342 females) spanning ages 12 to 18 years old at baseline. On average, irritability was stable across assessment points and defiance declined. Within time, associations of irritability with internalizing were consistently stronger than associations of irritability with conduct problems. Defiance was similarly associated within time with both internalizing and conduct problems in mid-adolescence, but was more highly related to internalizing than to conduct problems by early adulthood (ages 18 to 25). Over time, increasing irritability was related to changes in both internalizing and conduct problems; whereas increases in defiance predicted increases in conduct problems more strongly than internalizing symptoms. Increases in both internalizing and conduct problems were also associated with subsequent increases in both irritability and defiance. Sex differences in these associations were not significant.

Keywords: Comorbidity, Conduct disorder, Depression, Anxiety, Internalizing, Oppositional defiant disorder, Irritability, Defiance, Emerging adulthood, Adolescence

Mental health problems can disrupt salient developmental tasks of young adulthood including educational attainment, work experience, and interpersonal functioning (Graber and Sontag 2009). Symptoms of internalizing and externalizing are among the most common mental health concerns in adolescence and young adulthood (Costello et al. 2011). Subclinical symptoms of mental health problems in adolescence predict full syndrome disorders (Shankman et al. 2009) and this research suggests paths that may increase these risks. Although externalizing problems typically decline, internalizing symptoms show considerable stability or increase across this transition; moreover, the co-occurrence between a variety of internalizing and externalizing symptoms continues to be strong (Copeland et al. 2009; Costello et al. 2011; Leadbeater et al. 2012). A better understanding of the mechanisms that influence the stability of and the links between internalizing and externalizing problems across this transition is needed to provide targets for intervention. Following recent research (see reviews by Chen 2012; Burke and Loeber 2010; Frick and Nigg 2012) showing that sub-dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder (irritability and defiance) may differentially predict internalizing (depression and anxiety) and externalizing problems (conduct disorders and hyperactivity) in pre-school, childhood and adolescence; we investigate these links across the transition to young adulthood in a large community-based sample of youth, spanning ages 12 to 25 years old.

Oppositional defiant disorder is typically considered a problem of childhood that is either self-limiting or evolves into more serious conduct disorders with deviant and aggressive behaviours by late adolescence. Hence, the continuities and discontinuities in oppositional defiant symptoms (ODS), their comorbidity with internalizing, and their longer term effects on mental health in young adulthood remain poorly understood. We argue here that the distinction between irritable and defiant sub-dimensions of oppositionality may contribute to a better understanding of the links between internalizing and externalizing across the transition to young adulthood and inform interventions that can address the potentially disruptive effects of these mental health problems on academic, occupational, and interpersonal functioning.

Previous research (Leadbeater et al. 2012) with four waves of data from the current community-based sample of youth showed that, on average, trajectories of overall symptoms of oppositional defiance (ODS) were stable in youth across 12 to 22 years of age. ODS co-occurred with depressive symptoms at each wave of data collection and increases in ODS were associated with increases in symptoms of depression across time. However, these correlational findings did not address the direction of effects of these associations and the irritable and defiant sub-dimensions of ODS were not considered. The current study addresses three questions: 1. Can irritable and defiant sub-dimensions of ODS be distinguished from early adolescence to young adulthood and are measures invariant across time and sex? 2. What are the trajectories of irritability and defiance from early adolescence to young adulthood and do these co-vary with the trajectories of internalizing and externalizing problems? and 3. Do irritability and defiance differentially predict symptoms of depression and conduct problems across the transition from late adolescence to young adulthood? We first briefly review the research on the ODS sub-dimensions that has focused on the prediction of internalizing symptoms and conduct problems in childhood and adolescence.

Sub-dimensions of Oppositional Defiant Disorders

Research conducted with community-samples (Ezpeleta et al. 2012; Krieger, et al. 2013; Stringaris and Goodman 2009; Stringaris et al. 2013; Rowe, Costello, Angold, Copeland, and Maughan 2010; Whelan et al. 2013) or clinic-referred children and adolescents (Burke 2012; Burke and Loeber 2010; Drabick et al. 2010; Drabick and Gadow 2012) has distinguished two, or in some cases three, sub-dimensions of ODS symptoms. These have been variously labelled (and constructed), but they typically follow Stringaris and Goodman (2009) in differentiating between symptoms of 1) negative affect/irritable, 2) headstrong/defiant/antagonistic behaviors, and 3) spiteful/vindictive or callous behaviors. Items comprising the irritability dimension suggest a common theme reflecting emotional dysregulation or anger management problems (e.g. cranky, touchy, temper tantrums, easily annoyed, angry). In contrast, items included in the defiant dimension (e.g. argues with adults, defies or refuses to comply, deliberately annoys people, blames others) are typically conceptualized as individual behavioral problems or reactions to coercive parent–child interactions (Aebi et al. 2010). However, items used to measure defiance focus attention on problematic interpersonal interactions that may also involve non-family interactions. In children and adolescents, defiance against authorities typically targets parents, siblings, and teachers. However, by late adolescence and young adulthood, it is possible that these negative interactions also involve other significant relationships including employers, peers, and romantic partners, and conceptualizing defiance as interpersonal problems may aid in focusing interventions. The irritability and defiance sub-dimensions are also distinguished from behaviors involving the perpetration of callous-unemotional acts or spiteful retaliation and are manifested in deliberately hurting others without regard to their suffering (Kolko and Pardini 2010). An advantage of these distinctions is that they go beyond a broad conceptualization of oppositional defiant disorders as behavioral problems and point more specifically to problems with the management of strong emotions, disruptions in stage-salient interpersonal relationships, and, occasionally, also callous behaviors.

The past research has also contributed to our understanding of linkages between these sub-dimension and increases in internalizing and externalizing problems in preschool, childhood and adolescence. Most research (Burke 2012; Burke, Hipwell, and Loeber 2010; Ezpeleta, et al. 2012; Stringaris and Goodman 2009) confirms that irritability is more strongly related to increases in depressive and anxious symptoms than externalizing problems. However, the headstrong/defiant and vindictive/spiteful dimensions are more strongly related to the development of externalizing (attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder ADHD or conduct disorders) in some studies (Ezpeleta et al. 2012; Stringaris and Goodman 2009; Whelan et al. 2013), but predict both depression and externalizing in others (Rowe et al. 2010).

Inconsistencies in past findings may relate, in part, to the distribution of items used to distinguish among the dimensions. These are based on a priori classifications in some studies and on exploratory factor analyses (EFA) in others (see review by Burke and Loeber 2010). Given that findings based on EFAs tend to be sample specific and not easily generalized (Fabrigar et al. 1999), it is perhaps not surprising that item loadings differ across studies with samples that differ by source of the data, levels of pathology, location, age, ethnicity, and sex. For example, the item “often loses temper” is categorized a priori with the irritable dimension in a cross-sectional study of British children and youth ages 5 to 16 (Stringaris and Goodman 2009), and also in a longitudinal study of children and youth ages 9 to 21 from the United States Great Smoky Mountains Study using EFA (Rowe et al. 2010). However, in an EFA of data from the Pittsburgh Girls’ Study (Burke et al. 2010; Hipwell et al. 2011) with girls ages 8 to 16, temper tantrums loaded on the defiance (behavioral) factor along with arguing and defying; whereas the irritable (affective) factor included being angry, touchy, and spiteful; and annoying and blaming others loaded onto a third factor labelled antagonistic. The item “spiteful” also loaded on the defiant/headstrong factor in Rowe et al. (2010), but not elsewhere (Burke and Loeber 2010).

To address these measurement problems, we adopt a theoretical approach and use confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to clearly distinguish between items that assess either irritable mood or defiance that is clearly linked to interpersonal interactions. To increase the conceptual validity of these distinctions, we also exclude ODS symptoms that cannot be clearly differentiated into one of these categories in young adulthood. For example, temper tantrums can be conceptualized as angry outbursts reflecting irritability in childhood and early adolescence, but temper may have a greater range of manifestations in young adults (including anger, sulking, stalking off, aggressive behaviors, or damaging property). Given this diversity in expression, past inconsistencies in loadings of temper tantrums, and the need for a common measure that reaches from adolescence to young adulthood in this longitudinal study; we omit the item assessing temper tantrums from our analyses. Similarly, spiteful/vindictive behaviors are typically tapped by one item and occur infrequently even in children with a clinical diagnosis of ODS (Keenan 2012) and are not clearly related to irritability or defiance. Hence, these symptoms are also omitted from our measure.

In this study we extend previous research on the psychometrics of the sub-dimensions of ODS using confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to assess the measurement invariance across sex and age groups from adolescence to young adulthood. We use five waves of data from a large, community-based sample that was followed across 8 years, spanning ages 12 to 25. Next, we examine the average univariate trajectories of each of these sub-dimensions across this transition and assess their co-variation with internalizing symptoms (depression and anxiety) and conduct problems. Finally, we also test the differential effects of irritability and defiance on concurrent and subsequent levels of internalizing symptoms and conduct problems. Given that some cycling of symptoms may be established by late adolescence, we also compare the fit of models specifying both unidirectional and reciprocal relations among internalizing and conduct disorder and irritability and defiance over time. Sex differences in levels of internalizing, oppositional defiant disorders and conduct problems are well established (Costello et al. 2011; De Ancos and Ascaso 2011; Munkvold et al. 2011) and are also tested in each model.

Methods

Participants

Data were drawn from the Victoria Healthy Youth Survey (V-HYS), which was administered biennially from 2003 to 2011 (see Leadbeater et al. 2012 for details). Participants were recruited from a random sample of 9,500 telephone listings; 1,036 households with an eligible youth (aged 12 to 18 years) were identified. Of these, 185 parents or guardians and 187 youth refused participation. At baseline, participants included 662 youth (342 females). Youth were 85 % European-Canadian, 4 % Asian, and 11 % other ethnicities. Nineteen percent of fathers and 19 % of mothers finished high school only, and 43 % of fathers and 49 % of mothers completed college or university training. The majority (55 %; n=361) lived with both of their biological or adoptive (1.7 %; n=11) parents; 42.6 % of youth were from families with parents who were separated or divorced, and, 2 % of youth (n=13) had a parent who died. Response rates were 87 % (n=578) at Time 2, 81 % (n=539) at Time 3, 70 % (n=459) at Time 4, and 70 % (n=464) at Time 5. Attrition analyses of differences in initial status for participating and non-participating youth comparing T1 and T5 showed that attrition was not related to the demographic or study variables.

Youth gave written consent for their participation at each wave and received a gift certificate for their participation at each interview. A trained interviewer administered the V-HYS in individual interviews in the youth’s home or another private place. Skype or phone interviews in later waves were also used when necessary to follow youth who moved or were travelling. To enhance privacy and increase responding, the portion of the V-HYS questionnaire dealing with private topics (including the mental health symptoms) is read by the interviewer, but is filled in privately by the individual and placed in a sealed envelope that is never accessible to the interviewer. While the validity of self-report data has been debated (e.g., Beggs et al. 1999), recent research by Bradford and Rickwood (2012) demonstrates that self-administered assessments are the most accepted form of psychosocial screening instruments in young adults, and that these enhance engagement and improve rates of disclosure.

Measures

All measures were collected by self-report at each time point, except for conduct problems which were only assessed at T3, T4, and T5.

Symptoms of internalizing (anxiety and depression) and oppositional defiance were assessed with the Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (BCFPI; Cunningham et al. 2009). The BCFPI was developed for standardized intake screening and outcome evaluation for children 6 to 18 years of age. Items on the BCFPI specifically reflect DSM-IV criteria for different child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. An evaluation of the BCFPI instrument by Boyle et al. (2009) concluded that it provided a “reasonable approximation to disorders classified by the DISC-IV [Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version IV]” (p. 424), an accepted standard for classifications of disorders.

Assessments included 6 items for each symptom category rated on a three-point scale (i.e., 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, or 2 = often) in response to the question, “Do you notice that you [… item]”. The items for anxiety symptoms are: (1) worry about your past behavior (2) worry about doing the wrong thing (3) worry about doing better at things? (4) are overly anxious to please people (5) are afraid of making mistakes and (6) worry about things in the future? Items for the depression symptoms are: (1) feel hopeless (2) get no pleasure from your usual activities (3) have trouble enjoying yourself (4) are unhappy, sad or depressed (5) have no interest in your usual activities and (6) are not as happy as people your age? Items for the ODS symptoms included three irritability items: (1) are easily annoyed by others (2) are angry and resentful (3) are cranky (irritable)?; as well as three defiance items (4) are defiant, or that you talk back to people (5) argue a lot with others and (6) blame others for your own mistakes?. Following Gadermann et al. (2012), reliability estimates (alphas) for these ordinal scales were obtained using polychoric correlations. Alphas were 0.90 for depression at each wave and ranged from 0.82 to 0.87 for anxiety and from 0.80 to 0.84 for ODS (total score). Alpha for internalizing (with symptoms of anxiety and depression combined) ranged from 0.89 to 0.92.

Despite the face validity of the items, the BCFPI questionnaire has not typically been used with individuals older than 18. Nevertheless, continuity in measures is important for longitudinal research. Hence, we tested the invariance across time and sex for symptoms of anxiety, depression and total ODS (see Leadbeater et al. 2012). Findings supported the configural (i.e., equality of number of salient factor loadings) and metric factorial invariance (i.e., equality of magnitude of factor loadings) across time and sex. Scalar invariance (i.e., equal intercepts) was not found. Findings were similar using the 5 waves of data used in this study and are not repeated here. In the current study, we also examined the metric properties and invariance of the sub-dimensions of the ODS sub-scales across time and sex. Polychoric alphas for the irritability sub-dimension ranged from 0.77 to 0.81 and for the defiance sub-dimension from 0.61 to 0.71.

Conduct Problems were assessed using seven items that tapped DSM-IV symptoms of conduct disorders. Youth were asked “In the past year, how often have you […item].” Responses were rated on a four-point scale (i.e., 0 = never, 1 = once or twice, 2 = several times, or 3 = very often). Items were a range of conduct problems that differed in severity: (1) given a fake excuse for missing work, not showing up for a meeting, or cutting class; (2) borrowed money from someone without any intention of paying it back; (3) damaged public or private property that didn’t belong to you; (4) started a fight and struck someone because you didn’t like what that person said or did; (5) given false information in filling out an application for a job, or a loan, or something else like that; (6) taken something of value from a store without paying for it; and (7) broken into a place that was locked just out of curiosity. Due to the low occurrence of ratings exceeding “once or twice”, responses were scored 1 if the behavior occurred and 0 if not; total scores ranged from 0 to 7 and were approximately normally distributed. Alphas (polychoric correlations) ranged from 0.75 to 0.82.

Socio-economic status (SES) was assessed as a rating of mother’s education on a five-point scale; 0 = less than high-school, 1 = high-school, 2 = vocational training, 3 = some college/university, 4 = finished college/university (M=3.93, SD=1.35).

Plans for Analyses

To examine ODS sub-dimensions and their associations with internalizing and conduct problems from adolescence to young adulthood, the five waves of data were rearranged based on the participant’s age at each interview. Data were grouped in 2-year age intervals (i.e. ages 12–13, 14–15, 16–17, 18–19, 20–21, 22–23 and 24–25) to maintain adequate power for analyses. Observations at ages 26–27 were not included due to low covariance coverage across time. Conduct problems were observed beginning at age 16–17, given these data were not collected at earlier ages.

All models were fit using MPlus 7.11 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012) using full-information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data. Standard indices were used to assess the fit of the models (i.e. RSMEA≤0.08; Comparative fit Index (CFI)≥0.95 are used to delineate adequate fit). Data were initially run with symptoms of anxiety and depression considered separately; however, correlations between these internalizing symptoms were moderate to strong (r=0.36 to 0.59) and findings for each symptom type were nearly identical so these were combined to form an overall measure of internalizing to reduce redundancy in reporting the results.

CFAs were used to compare the goodness-of-fit between the hypothesized 2-factor model and a 1-factor model for each age separately. In the 2-factor model, Factor 1 included the irritability items and Factor 2 included the defiance items. We also tested the invariance of the 2-factor model across time and sex; comparing configural (comparing baseline models with one fixed loading per factor), weak (constraining corresponding loadings to be equal), and strong (constraining the intercepts to be equal) invariance. Strict invariance (constraining residuals to be equal) was tested but not supported. All models were compared using the difference between CFI, RMSEA, and χ2 values. A CFI or RSMEA difference between models of <0.01 is considered invariant (Bontempo and Hofer 2007; Little 2013).

Univariate latent growth curve models were used to describe trajectories of irritability, defiance, internalizing symptoms, and conduct problems over time. Time was represented as age, with 2 person-years between each time point (age 12–13=0, 14–15=2, 16–17=4, 18–19=6, 20–21=8, 22–23=10, 24–25=12). Because conduct problems was not measured at T1 or T2, this model examined the trajectory of conduct problems starting at age 16–17. Each model also accounted for the heterogeneity in SES (mother’s education). Sex differences were tested by comparing model fit with and without constraints on model parameters for males and females. We also estimated a multivariate growth model that included all four trajectories. In this model time was centered at age 16–17. The slopes (rates of change) were regressed on intercepts (initial levels) and co-variations among all growth factors were examined.

Finally, to examine age differences in the patterns of change over time, we compared the model fit of a sequence of path models to examine the expected differential effects of irritability and defiance on internalizing symptoms and conduct problems from adolescence to young adulthood. The baseline model (Model 1) included autoregressive paths and within-time covariances only. In Model 2, we examined lagged paths from the ODS sub-dimensions to subsequent assessments of internalizing and conduct problems; whereas in Model 3 we included lagged paths from internalizing and conduct problems to subsequent ODS sub-dimensions. Finally, combining Models 2 and 3, we examined a reciprocally cross-lagged model, Model 4. Paths involving conduct problems were assessed from age 16–17 onwards.

Sex differences were examined for Model 4 by comparing changes in model fit resulting from imposing and releasing equality constraints on each of the model parameters for males and females following a bottom-up stepwise procedure (moving from an unconstrained model to a fully constrained model) as recommended by Bollen and Curran (2006). Comparisons of the differences in log-likelihoods and the degrees of freedom between the models were used to test the null hypothesis that the more restricted model fit as well as the less restrictive model.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means for males and females are presented in Table 1. Males reported higher scores for defiance at ages 18–19 and 20–21, and more conduct problems at most ages. Females reported more irritability at 16–17 and more internalizing at 14–15. The inter-correlations among symptom domains were significant at each time point (correlation matrix is available from the authors). The irritability and defiant dimensions were positively correlated with internalizing symptoms and conduct problems within and across time. As expected, at each assessment point, irritability was correlated more strongly with internalizing symptoms (range in r=0.23 to 0.60) than with conduct problems (range in r=0.08 to 0.24). In contrast, defiance was similarly related to both internalizing symptoms (range in r=0.11 to 0.45) and conduct problems (range in r= 0.15 to 0.40).

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations by sex

| Males

|

Females

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F(df) | N | Range | |

| Irritability | |||||||

| 12–13 | 2.05 | 1.25 | 1.89 | 1.21 | 0.71 | 173 | 0–6 |

| 14–15 | 2.08 | 1.37 | 2.35 | 1.43 | 3.3 | 343 | 0–6 |

| 16–17 | 2.13 | 1.37 | 2.45 | 1.38 | 6.96** | 526 | 0–6 |

| 18–19 | 2.26 | 1.32 | 2.35 | 1.40 | 0.51 | 485 | 0–6 |

| 20–21 | 2.16 | 1.43 | 2.17 | 1.31 | 0.01 | 436 | 0–6 |

| 22–23 | 2.09 | 1.48 | 2.20 | 1.28 | 0.57 | 325 | 0–6 |

| 24–25 | 2.17 | 1.38 | 2.14 | 1.30 | 0.02 | 244 | 0–6 |

| Defiance | |||||||

| 12–13 | 2.14 | 1.31 | 1.95 | 1.45 | 0.81 | 173 | 0–6 |

| 14–15 | 2.12 | 1.37 | 2.17 | 1.38 | 0.14 | 343 | 0–6 |

| 16–17 | 2.08 | 1.27 | 1.91 | 1.29 | 2.36 | 526 | 0–6 |

| 18–19 | 2.04 | 1.28 | 1.64 | 1.27 | 11.97*** | 485 | 0–6 |

| 20–21 | 1.79 | 1.28 | 1.39 | 1.13 | 12.16*** | 436 | 0–5 |

| 22–23 | 1.52 | 1.15 | 1.37 | 1.19 | 1.38 | 325 | 0–5 |

| 24–25 | 1.46 | 0.98 | 1.22 | 1.24 | 2.86 | 244 | 0–5 |

| Internalizing symptoms | |||||||

| 12–13 | 7.07 | 3.58 | 7.54 | 4.24 | 0.60 | 173 | 0–19 |

| 14–15 | 7.84 | 3.93 | 9.03 | 4.43 | 6.77** | 343 | 0–23 |

| 16–17 | 8.96 | 4.19 | 9.65 | 4.22 | 3.51 | 526 | 1–22 |

| 18–19 | 9.49 | 4.38 | 10.08 | 4.70 | 1.98 | 485 | 0–24 |

| 20–21 | 9.54 | 4.30 | 9.48 | 4.61 | 0.02 | 436 | 0–24 |

| 22–23 | 9.33 | 4.78 | 9.22 | 4.48 | 0.05 | 325 | 0–24 |

| 24–25 | 8.37 | 4.82 | 8.74 | 4.84 | 0.37 | 244 | 0–21 |

| Conduct problems | |||||||

| 16–17 | 2.10 | 1.67 | 2.19 | 1.61 | 0.11 | 141 | 0–6 |

| 18–19 | 2.13 | 1.56 | 1.46 | 1.27 | 13.15*** | 235 | 0–6 |

| 20–21 | 2.01 | 1.66 | 1.31 | 1.02 | 25.09*** | 368 | 0–7 |

| 22–23 | 1.88 | 1.47 | 1.15 | 0.98 | 28.43*** | 325 | 0–7 |

| 24–25 | 1.43 | 1.27 | 1.23 | 1.21 | 1.59 | 244 | 0–7 |

| SES | 3.87 | 1.36 | 3.89 | 1.39 | 0.05 | 658 | 1–5 |

p<0.01

p<0.001

Comparisons of 1-Factor and 2-Factor Models of ODS Sub-dimensions

Table 2 shows the results of confirmatory factor analyses for the 1- and 2-factor models of ODS sub-dimensions at each age, as well as comparisons of goodness-of-fit for the two models. Comparison of goodness-of-fit showed that the 2-factor model was a better fit at every age except for age 24–25, when the 2-factor model fit the data as well as the 1-factor model. Model fit for the hypothesized two-factor model was adequate at each age, except for the 12 to 13 year age group – possibly reflecting the N available for this group (see Table 3). Factor loadings were above 0.40 (except for blames others). Consistent with the literature suggesting that irritability and defiance are distinct but related symptoms of ODS, correlations between the factors were strong at each time point (0.70–0.89).

Table 2.

Comparison of confirmatory factor analyses for 1- and 2-factor models of ODS Sub-dimensions from Ages 12–13 to 24–25

| Age | 12–13 | 14–15 | 16–17 | 18–19 | 20–21 | 22–23 | 24–25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-factor model fit | |||||||

| χ2 (df=9) | 30.51*** | 22.37** | 34.66*** | 43.54*** | 17.62* | 18.16* | 18.00* |

| RMSEA | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| CFI | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| 2-factor model fit | |||||||

| χ2 (df=8) | 21.46** | 6.74 | 20.18** | 33.79*** | 12.20 | 6.65 | 14.74† |

| RMSEA | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| CFI | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| Model comparisons | |||||||

| Δχ2 (df=1) | 9.05** | 15.63*** | 14.48*** | 9.75** | 5.42* | 11.51*** | 3.26 |

| ΔRMSEA | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.00 |

| ΔCFI | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

Δχ2 =differences in x2 values

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

p=0.06

Table 3.

Factor loadings for confirmatory factor analysis of ODS Sub-dimensions from Ages 12–13 to 24–25

| Factor loadings

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12–13 Est (SE) |

14–15 Est (SE) |

16–17 Est (SE) |

18–19 Est (SE) |

20–21 Est (SE) |

22–23 Est (SE) |

24–25 Est (SE) |

|

| Item | |||||||

| Do you notice that you…? | |||||||

| Irritability | |||||||

| are easily annoyed by others | 0.48 (0.09) | 0.58 (0.05) | 0.62 (0.04) | 0.65 (0.04) | 0.62 (0.04) | 0.61 (0.05) | 0.63 (0.06) |

| are cranky | 0.52 (0.09) | 0.59 (0.05) | 0.61 (0.04) | 0.62 (0.04) | 0.63 (0.04) | 0.64 (0.05) | 0.57 (0.06) |

| are angry and resentful | 0.64 (0.09) | 0.73 (0.04) | 0.63 (0.04) | 0.66 (0.04) | 0.74 (0.03) | 0.68 (0.05) | 0.69 (0.05) |

| Defiance | |||||||

| are defiant, or that you talk back to people | 0.83 (0.06) | 0.70 (0.04) | 0.64 (0.05) | 0.67 (0.04) | 0.57 (0.04) | 0.58 (0.05) | 0.64 (0.07) |

| argue a lot with others | 0.70 (0.06) | 0.71 (0.04) | 0.56 (0.05) | 0.64 (0.04) | 0.68 (0.04) | 0.69 (0.05) | 0.52 (0.07) |

| blame others for your own mistakes | 0.38 (0.08) | 0.39 (0.06) | 0.37 (0.05) | 0.40 (0.05) | 0.37 (0.05) | 0.38 (0.06) | 0.43 (0.07) |

| Correlation between factors | 0.70 (0.10) | 0.81 (0.05) | 0.78 (0.06) | 0.85 (0.05) | 0.89 (0.05) | 0.80 (0.06) | 0.86 (0.08) |

| χ2(df)=8 | 21.46** | 6.74 | 20.18** | 33.79*** | 12.20 | 6.65 | 14.74† |

| RMSEA | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| CFI | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| N | 173 | 343 | 526 | 485 | 436 | 325 | 244 |

p<0.01

p<0.001

p=0.06

Measurement Invariance in Irritability and Defiance Measures Across Time and Sex

As shown in Table 4, weak invariance (magnitude of factor loadings) was indicated across time and for sex by changes in CFI or RSMEA<0.01. Strong invariance (invariant intercepts) was not found over time, but freeing the constraint on the intercept for the “are defiant or talk back” item at ages 18–19 to 24–25 reduced the change in the respective model fit indices – suggesting partial strong invariance over time. Strong invariance across sex was found at ages 12–13, 14–15, and 24–25. At ages 16–17 and 22–23, freeing the constraint on the intercept for the “cranky” item confirmed partial strong invariance between males and females. To facilitate interpretation of the findings, total scale scores were used in subsequent analyses rather than latent variables based on factor scores (Brown 2006).

Table 4.

Summary of Measurement Invariance of Irritability and Defiance Over Time and Sex

| Invariance | Compared to model | χ2(df) | Δχ2 (df) | RMSEA | CFI | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By Time | Configurala | – | 770.40 (576)*** | – | 0.02 | 0.95 | – | – |

| Weakb | Configural | 794.21 (600)*** | 23.81 (24) | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.00 | |

| Strongc | Weak | 936.48 (611)*** | 142.27 (11)*** | 0.03 | 0.92 | −0.04 | 0.01 | |

| Partial strong (intercepts of “defiant” item freed at ages 18–19, 20–21, 22–23 and 24–25) | Weak | 799.04 (607)*** | 4.83 (7) | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| By Sex | ||||||||

| 12–13 | Configurala | – | 32.25 (16)** | – | 0.12 | 0.90 | – | – |

| Weakb | Configural | 47.18 (22)** | 11.92 (6) | 0.12 | 0.87 | −0.03 | 0.00 | |

| Strongc | Weak | 54.77 (28)** | 7.59 (6) | 0.11 | 0.86 | −0.01 | −0.01 | |

| 14–15 | Configural | – | 18.29 (16) | – | 0.03 | 0.99 | – | – |

| Weak | Configural | 19.89 (22) | 1.60 (6) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.01 | −0.03 | |

| Strong | Weak | 33.12 (28) | 12.28 (6)†+ | 0.03 | 0.99 | −0.01 | 0.03 | |

| 16–17 | Configural | – | 24.28 (16) | – | 0.04 | 0.98 | – | – |

| Weak | Configural | 25.37 (22) | 1.09 (6) | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.01 | −0.02 | |

| Strong | Weak | 53.03 (28)** | 27.67 (6)*** | 0.06 | 0.95 | −0.04 | 0.04 | |

| Partial strong (intercept of ‘cranky’ item on irritability factor freed) | Weak | 33.82 (27) | 8.45 (5) | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| 18–19 | Configural | – | 39.46 (16)*** | – | 0.08 | 0.96 | – | – |

| Weak | Configural | 47.57 (22)** | 8.11 (6) | 0.07 | 0.96 | 0.00 | −0.01 | |

| Strong | Weak | 104.27 (28)*** | 56.70 (6)*** | 0.11 | 0.87 | −0.09 | 0.04 | |

| Partial strong (intercepts of ‘cranky’ item on irritability factor and ‘argue’ item on defiance factor freed) | Weak | 56.54 (26)*** | 8.97 (4) | 0.07 | 0.95 | −0.01 | 0.00 | |

| 20–21 | Configural | – | 30.90 (16)* | – | 0.07 | 0.97 | – | – |

| Weak | Configural | 36.58 (22)* | 5.68 (6) | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.00 | −0.01 | |

| Strong | Weak | 71.13 (28)*** | 34.55 (6)*** | 0.08 | 0.92 | −0.05 | 0.02 | |

| Partial strong (intercepts of ‘cranky’ item on irritability factor and ‘argue’ item on defiance factor freed) | Weak | 45.81 (26)** | 9.23 (4)† | 0.03 | 0.96 | −0.01 | −0.03 | |

| 22–23 | Configural | – | 16.00 (16) | – | 0.00 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Weak | Configural | 20.47 (22) | 4.48 (6) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Strong | Weak | 33.87 (28) | 13.39 (6)* | 0.04 | 0.98 | −0.02 | 0.04 | |

| Partial strong (intercept of ‘cranky’ item on irritability factor freed) | Weak | 25.48 (27) | 5.01 (5) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 24–25 | Configural | 19.13 (16) | – | 0.04 | 0.99 | – | – | |

| Weak | 30.22 (22) | 11.09 (6) | 0.06 | 0.97 | −0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| Strong | 39.03 (28) | 8.81 (6) | 0.06 | 0.95 | −0.02 | 0.00 | ||

Δχ2 =differences in χ2 values

An unconstrained model with parameters freely estimated

Path loadings for each indicator were constrained to be equal across time or sex

The intercepts for each indicator were constrained to be equal across time or sex

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

p=0.06

Univariate Trajectories of Irritability, Defiance, Internalizing Symptoms and Conduct Problems from Adolescence to Young Adulthood

Table 5 summarizes results of latent growth models for the ODS sub-dimensions, internalizing symptoms, and conduct problems for males and females. All models showed adequate fit to the data. Intercepts differed significantly as expected -with slightly higher scores for males than females for each symptom type except internalizing. Variances for all intercepts and slopes were significant. On average, irritability slopes were not significant indicating that these symptoms were typically stable over time. When all parameters were constrained (including growth factor means, variances, covariances, and residuals) for males and females, the model fit as well as a model in which they were freed (Δχ2(14)=11.21, p=0.67), indicating that sex differences in the trajectory of irritability were not significant. On average, defiance decreased over time. Tests of sex differences for defiance showed that females had a greater decline over time (Δχ2(1) = 6.83, p = 0.01). Internalizing symptoms first increased, then decreased, over time, with males reporting a steeper rate of increase (Δχ2(16)= 31.21, p=0.01). Finally, conduct problems declined on average from age 16–17 to age 24–25. Females showed a steeper rate of decline that males (Δχ2(12)=90.21, p<0.001).

Table 5.

Summary of Univariate Growth Models for Irritability, Defiance, Internalizing Symptoms, and Conduct Problems

| Intercept mean Est. (SE) |

Intercept variance Est. (SE) |

Slope mean Est. (SE) |

Slope variance Est. (SE) |

Quadratic meana Est. (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irritability (ages 12–13 to 24–25) | |||||

| Males | 2.55 (0.31)*** | 1.00 (0.01)*** | 0.17 (0.30) | 1.00 (0.01)*** | – |

| Females | 2.41 (0.25)*** | 1.00 (0.01)*** | −0.09 (0.28) | 1.00 (0.01)*** | – |

| SES | −0.07 (0.06) | – | −0.07 (0.09) | – | – |

| Model fit | χ2 (69)=128.25** RMSEA=0.05. CFI=0.92. N=657 | ||||

| Defiance (ages 12–13 to 24–25) | |||||

| Males | 2.24 (0.25)*** | 1.00 (0.00)*** | −0.81 (0.28)** | 1.00 (0.01)*** | – |

| Females | 2.10 (0.25)*** | 1.00 (0.00)*** | −0.83 (0.27)*** | 1.00 (0.01)*** | – |

| SES | 0.00 (0.06) | – | −0.04 (0.08) | – | – |

| Model fit | χ2 (63)=87.51* RMSEA=0.03. CFI=0.96. N=657 | ||||

| Internalizing (ages 12–13 to 24–25) | |||||

| Males | 7.64 (0.81)*** | 10.15 (1.79)*** | 5.61 (2.45)* | 17.52 (3.57)*** | −4.07 (1.87)* |

| Females | 8.87 (0.77)*** | 12.57 (1.83)*** | 4.29 (2.30)+ | 9.78 (2.61)*** | −3.86 (1.78)* |

| SES | −0.21 (0.18) | – | 0.42 (0.54) | – | – |

| Model fit | χ2 (66)=101.50** RMSEA=0.04. CFI=0.96. N=657 | ||||

| Conduct problems (ages 16–17 to 24–25) | |||||

| Males | 2.21 (0.34)*** | 0.99 (0.01)*** | −1.79 (0.65)** | 0.93 (0.07)*** | – |

| Females | 2.02 (0.39)*** | 0.98 (0.03)*** | −0.95 (0.28)*** | 0.96 (0.03)*** | – |

| SES | −0.11 (0.06)+ | – | 0.26 (0.13)* | – | – |

| Model fit | χ2 (26)=44.17* RMSEA=0.05. CFI=0.90. N=578 | ||||

For identification, the variance of the quadratic growth factor for internalizing was set to zero

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001. Standardized estimates are shown

Results from the multivariate latent growth model with time centered at age 16–17 showed that intercepts of irritability, internalizing symptoms, and conduct problems were all positively correlated (range r=0.22–0.78, p<0.05). The linear slope of internalizing was correlated with the slope of irritability (r= 0.68, p<0.001) and the slope of defiance (r=0.77, p<0.001). The slope of conduct problems was significantly correlated with the slope of defiance (r=0.45, p=0.004), but not with the slope of irritability (r=0.30, p=0.12). The slopes of irritability and defiance were also positively correlated over time. None of the intercepts were significant predictors of slopes, showing that initial levels did not predict changes over time.

Do irritability and defiance differentially predict symptoms of internalizing and conduct problems?

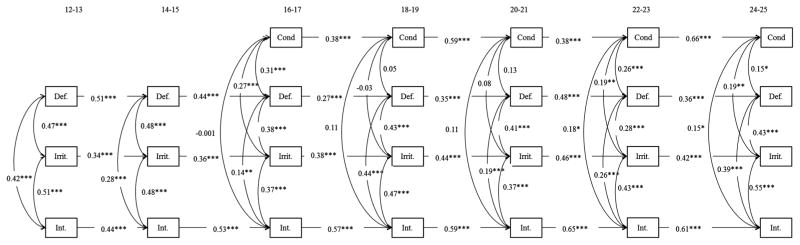

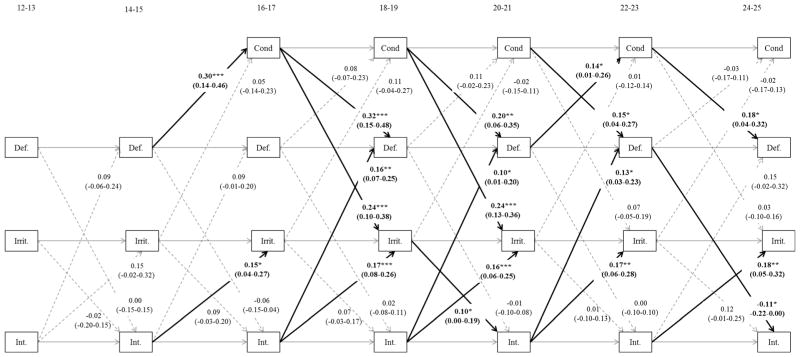

Nested multivariate path models were used to test the concurrent and directional relations among the ODS subtypes, internalizing and conduct problems across age groups (see Table 6). The baseline autoregressive model (Model 1), included only within-time covariances and autoregressive pathways and was a poor fit to the data. Adding unidirectional pathways from either irritability and defiance to subsequent internalizing and conduct problems (Model 2) or from internalizing and conduct problems to subsequent ODS dimensions (Model 3) each resulted in improved fit indices. Further, the fully cross-lagged model (Model 4) showed improved fit over both Models 2 and 3. To test for sex differences in Model 4, we compared a models with all paths constrained (covariances, autoregressive and cross-lagged paths, intercepts, and residuals) to a model in which paths were freely estimated. These models did not differ significantly (Δχ2(103)=119.21, p=0.13). Based on Model 4 for the total sample, we present the standardized estimates for autoregressive and within-time correlations in Fig. 1. To enhance readability, standardized estimates and confidence intervals for the significant cross lagged paths are reported in Fig. 2.

Table 6.

Comparisons of multivariate models testing relations among ODS Sub-dimensions and internalizing symptoms and conduct problems over time

| Model | Compared to model | χ2 (df) | RMSEA | CFI | Δχ2 (df) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Baseline autoregressive model | – | 714.67 (242)*** | 0.06 | 0.88 | – |

| 2. Adding pathways from ODS to conduct problems and internalizing symptoms | 1 | 651.98 (220)*** | 0.06 | 0.89 | 62.69 (22)*** |

| 3. Adding pathways from conduct problems and internalizing symptoms to ODS | 1 | 578.81 (222)*** | 0.05 | 0.91 | 121.91 (20)*** |

| 4. Reciprocally cross-lagged pathways | 2 | 530.07 (200)*** | 0.05 | 0.92 | 121.11 (20)*** |

| 3 | 48.74 (22)** |

All models control for sex and SES, and include autoregressive and within-time covariances

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Fig. 1.

Within-time covariances and autoregressive paths relating irritability and defiance to internalizing symptoms and conduct problems. Note: Cond conduct problems, Def defiance, Irrit irritability, Int internalizing. N=657. * p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001. Standardized estimates are shown. Cross-lagged paths also tested in this model are shown on Fig. 2 to enhance readability

Fig. 2.

Cross-lagged paths and confidence intervals relating irritability and defiance to internalizing symptoms and conduct problems over time. Note: Cond conduct problems, Def defiance, Irrit irritability, Int internalizing. N=657. * p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001. Standardized estimates are shown. Non-significant paths are dashed

Autoregressive paths and tests of the specificity of differences in within-time correlations for ODS sub-dimensions

As shown in Fig. 1, autoregressive pathways were moderately stable for irritability (range 0.34 and 0.46) and defiance (range 0.27 and 0 0.51) across each of the approximately 2-year time lags between assessments. Autoregressive paths for internalizing symptoms (range 0.44 to 0.65) and conduct problems after age 16 (range 0.38 to 0.66) were also significant. As expected based on past research, within-time correlations between irritability and internalizing were significantly larger than between irritability and conduct problems for each age group with data for conduct problems (χ2(1)=9.58 to 65.91, all p<0.01). Also at ages 16–17, the within-time correlation between defiance and conduct problems (0.31) was greater than between defiance and internalizing (0.14), but this difference was not significant (χ2(1)=0.02, p=0.88). Moreover, from age 18 to 19 onwards, the within-time correlations between defiance and internalizing were significantly larger than between defiance and conduct problems (χ2(1)=7.91 to 47.02, all p<0.01).

Longitudinal paths and tests of the specificity of differences in cross-time effects for ODS sub-dimensions with internalizing and conduct problems

The paths from irritability to internalizing were significant from only ages 18–19 to 20–21 (0.10, p<0.05), and paths from irritability to conduct problems not significant across any ages. However, a Wald test, used to compare the difference between paths from irritability to internalizing or to conduct problem showed that the pathways were not significantly different at any age (χ2 (5)=8.84, p=0.12).

The paths from defiance to conduct problems were significant between ages 14–15 to 16–17 and ages 20–21 to 22–23 (0.14, p<0.05), and paths from defiance to internalizing were also significant between ages 22–23 and 24–25 (−0.11, p<0.05). A Wald test of the difference between these pathways showed that paths from defiance to conduct problems were larger than paths from defiance to internalizing (χ2 (5)= 12.12, p=0.03), indicating that defiance more strongly predicted conduct problems than internalizing.

The paths from internalizing to irritability were significant across all ages and the paths from internalizing to defiance were significant between ages 16–17 to 18–19, ages 18–19 to 20–21, and 20–21 to 22–23. A Wald test comparing pathways from internalizing to either irritability or defiance showed these were not significantly different (χ2 (6)=6.76, p=0.34).

Finally, the paths from conduct problems to defiance were significant between all ages with available data, and paths from conduct problems to irritability were also significant between each age from 16–17 to 18–19 and from 18–19 to 20–21. A Wald test showed that paths from conduct problems to defiance were not significantly different to paths from conduct problems to irritability (χ2 (4)=4.74, p=0.34).

Discussion

This research adds to past work examining the differential relations among the irritability and defiant sub-dimensions of oppositional defiant disorders and internalizing symptoms and conduct problems. We contribute to this literature by theoretically distinguishing irritability as a problem with emotional management, from defiance as a problem in interpersonal interactions. We use CFAs to test the psychometric properties of self-report measures of these two constructs and show their invariance for males and females from ages 12 to 25. We describe the trajectories of these sub-dimensions in age groups spanning from early adolescence to young adulthood. Finally, we examined differences in the within- and across-time relations of these sub-dimensions with internalizing symptoms and conduct problems in the transition to young adulthood.

Our psychometric findings support the distinctiveness and stability of our two-factor measures of irritability and defiance and invariance in this factor structure (weak invariance) and intercepts (partial strong invariance) for males and females from ages 12 to 25. Univariate growth curve analyses showed that irritability, on average, was stable over this time period; whereas, defiance typically declined linearly from adolescence to young adulthood.

Our cross-sectional findings partially replicated previous research showing differential relations between irritability and internalizing (see reviews by Chen 2012; Burke and Loeber 2010; Frick and Nigg 2012). Within-time associations of irritability with internalizing were consistently stronger than with conduct problems. Defiance was similarly associated with both internalizing and conduct problems in mid-adolescence, but was more highly related to internalizing than to conduct problems by early adulthood (ages 18 to 25). Longitudinal analyses did not support differential predictions of irritability to internalizing or conduct problems; however, defiance predicted conduct problems more strongly than internalizing. While previous research has not examined the direction of these effects, we also found that increases in both internalizing and conduct problems were associated with increases in both irritability and defiance. This suggests that the cycling of internalizing and externalizing problems with irritability and defiance can be of significant concern in young adulthood. We discuss each of these findings, addressing each of our research questions.

Can irritable and defiant sub-dimensions of ODS be distinguished and measured from early adolescence to young adulthood and are measures invariant across time and sex?

While the expected high co-variation between irritability and defiance confirm that these are aspects of the broader construct of oppositional defiant disorder, CFAs supported their differentiation into a two factor model that provided good fit to the data at each wave and for both males and females. Factor loadings (weak invariance) were invariant across time and sex. Partial strong invariance in (intercepts) was supported at most age groups. However, item constraints needed to be released for “cranky” (for irritability) and “argue a lot” (for defiance) items, to establish partial strong invariance for data for both males and females. While there are clear benefits in using the same measure across time in this longitudinal research, caution is suggested for interpreting comparisons in latent means, separately for males and females (Bontempo and Hofer 2007). Further research may also improve the ability of this measure to better reflect the phenomenological experiences of irritability and defiance in young adult men and women. It is possible that the BCFPI terms like “cranky” or “talks back” are perceived as more childish by late adolescence and young adulthood compared to more commonly used terminology for self-reported symptoms at this age such as short-tempered or irritated (for cranky), and oppositional or insubordinate (for defiant). Equivalence of residual variances (strict) is rarely established (Little 2013) and was not supported here.

What are the trajectories of irritability and defiance from early adolescence to young adulthood?

Previous research has rarely assessed the changes in symptoms of irritability and defiance after age 18; however, our findings suggest that these symptoms continue to be a concern for some individuals. On average, irritability was stable over time whereas defiance declined linearly. Individual differences in these slopes were also significant, suggesting that irritability and defiance remain high or may increase for some youth. Increases in irritability also co-varied with increases in defiance.

The effects of higher levels of irritability and defiance on both mental health and the stage-salient outcomes of young adulthood (e.g. educational and occupational success and quality of romantic relationships) warrant further research. Irritability in early adolescence was related to income and educational attainment at age 20 in a study of British youth (Stringaris et al. 2009). It is possible that the continuation of symptoms like anger, irritably, or defiance from adolescence create increasing problems across this transition, particularly for occupational and relationship functioning of young adults. While such symptoms can be dismissed as normative aspects of the turmoil of adolescence, they are less likely to be tolerated in young adulthood.

Are irritability and defiance differentially associated with internalizing and conduct problems in young adulthood?

Consistent with previous research (Burke and Loeber 2010), our cross-sectional findings show that irritability (assessed as easily annoyed, angry and resentful, cranky) was more highly associated with internalizing symptoms than conduct problems for each age group. In contrast, defiance (assessed as talks back, argues, and blames others) was similarly related to both internalizing and conduct problems in the adolescent age groups, but was, unexpectedly, more related to internalizing than conduct problems from ages 18 to 19 onward. This may reflect the comparatively low levels of conduct problems in our community-based sample and findings may not generalize to a more deviant sample. However, the long term consequences of defiance may indeed be internalizing problems in non-deviant populations. Internalizing symptoms including hopelessness, sadness, or excessive worrying may sustain or be augmented by concurrent experiences of irritability or defiance. Alone, internalizing symptoms may evoke emotional support. However, internalizing accompanied by irritability (angry, touchy) or defiance may alienate support from close relationships, which, in turn, can reduce emotional support and fuel self-criticism and depression (Rudolph and Clark 2001; Leadbeater et al. 1999).

Do irritability and defiance differentially predict symptoms of depression and conduct problems across the transition from late adolescence to young adulthood?

The limited longitudinal research that is available shows sub-dimensions of ODS are related to subsequent pathology. For example in a clinic-referred sample, 7–12-year-old boys who had high levels of irritability at baseline were significantly more likely to show anxiety and depression in adolescence and at age 18 (Burke 2012). Irritability in early adolescence (about age 14) also predicted mood disorders at age 20 in a community-based sample (Stringaris et al., 2009). In addition, although oppositional defiant disorders are implicated in the onset of depression and conduct problems in childhood (Keenan 2012), the direction of effects of these symptoms has not been investigated in young adults. Our findings extend this research showing that increases in irritability and defiance may be associated with subsequent increases in externalizing and internalizing, but also that increasing levels of externalizing and internalizing are associated with increases in irritability and defiance.

Longitudinal finding for irritability

Findings in the current study showed no difference in the strength of the paths from prior irritability to later internalizing or conduct problem, and the path linking increases in irritability to increases in internalizing paths reached significance only from age 18–19 to 20–21 - a time of life typically marked by the multiple transitions that follow high school. Managing these strong negative emotions (anger, irritability, and resentment) may also be particularly difficult in the face of demands for adjusting to new work opportunities, educational pursuits, and peer networks. All paths were in the expected direction and it is possible that power for these complex analyses is not adequate to examine differences at each age.

A review by Drabick et al. (2010) suggests that the irritability may be related to a variety of concerns including child temperament differences, limbic system processes, executive functioning, and social information processing errors. Findings of genetic links for irritability also suggest that parents may be dealing with their own mental health problems in ways that compromise their ability to also parent mentally ill youth transitioning to young adulthood (Stringaris, Zavos, Leibenluft, Maughan, and Eley 2012). In the current research, irritability symptoms are elevated in the context of both existing and prior internalizing or externalizing; hence, irritability may be among the risk factors that initially create and also later sustain the co-occurrence of these problems. Burke and Loeber (2010, p. 319) argue for “optimizing early interventions aimed at reducing irritability in some oppositional children,” and we might add that such interventions may also be essential for adolescents and young adults with internalizing problems. Dialectical therapy, for example, adds a component of emotion-focused coping to a cognitive behavioral therapy approach and has begun to show evidence of effectiveness for adolescents with irritability symptoms (see review by MacPherson, Cheavens, and Fristad 2013).

Longitudinal findings for defiance

Increases in defiance were more strongly associated with increases in conduct problems than with increases in internalizing and this path reached significance between ages 14–15 and 16–17 and also between ages 20–21 and 22–23 and was in the expected direction at other age groups. It is not surprising that increases in defiance are associated with increases in conduct problems (assessed as giving fake excuses for absences; damaging property, and fighting). Interpersonal risk factors may also propel the associations of defiance with conduct problems (Aebi et al. 2010; Burke and Loeber 2010; Hames et al. 2013) and explain some of the comorbidity in these concerns. Coercive patterns of parent–child exchanges are common for children and adolescents with conduct disorders and these may extend to other authority figures in young adulthood. Both conduct problems and argumentative defiant approaches to conflict resolution in young adulthood can disrupt key developmental tasks of this age group including establishing the foundations for work and extra-familial emotional support, and romantic relationships. This may lead to short term work with cycles of unemployment and multiple short term relationships. Defiantly blaming others, arguing, and refusing to cooperate may also be used to deflect self-blame for these problems as they continue over time.

Youth engaged in conduct problems may elicit negative relationships with parents, employers and peers by arguing, refusing to comply, and blaming others, which in turn can elicit disciplinary actions and criticism from authorities. This may also enhance dysphoric self-critical styles (e. g. of feeling unfairly criticized by “everyone”) that are also related to increases in depressive disorders over time (Leadbeater, et al. 1999). Interventions for youth with conduct problems that focus directly on these interpersonal interaction concerns and that can disrupt and reduce the high correlations between irritability and defiance show some success (Moretti and Obsuth 2009) and warrant further investigation. While not assessed in this study, conduct problems are also often related to other problem behaviors such as alcohol and marijuana use over time and further research on these co-occurring concerns is needed.

It is also notable that both that increases in internalizing and in conduct problems were associated prospectively with increases in both irritability and defiance. While past research suggests ODD is a gateway to pathology in young children (Keenan 2012), established internalizing or externalizing pathology may serve to increase irritability and defiance in older adolescents and young adults and also become part of the mechanisms that sustain and fuel these problems over time. Links between internalizing and conduct problems may also be maintained though their associations with irritability and defiance. For example, Stringaris et al. (2009, p. 1052) argue that “anger” may stand at the interface between emotional and disruptive disorders, predicting internalizing when matched with fear and externalizing when it stands alone. Conduct problems that lead to higher levels of irritability or defiance may also make internalizing more likely by simultaneously compromising anger management, creating stress, and alienating others.

Limitations

This research contributes to and extends our understanding of the relations among self-reported irritability and defiance with internalizing symptoms and conduct problems in a community sample that followed youth across the transition to young adulthood, however, limitations related to our sample and measures must be noted. In particular, our Canadian community-representative sample is economically diverse, but is primarily Caucasian. Hence, the generalizability of our findings to clinic-referred and ethnic minority youth is not known.

Measurement difference may also limit the comparability of our research with previous literature. We omitted two items that are included in previous efforts to assess sub-dimensions of ODS with community and clinic-referred samples; namely, “has temper tantrums” and “is spiteful” (Burke and Loeber 2010). These items loaded inconsistently on irritable and defiant dimensions in past research and further research is needed to improve the assessment of these perhaps more strictly behavioral aspects of oppositional defiant disorders. It is also difficult to assume equivalence in meaning of temper tantrums in children and young adults. Temper tantrums may characterize irritability, especially in young children, but temper tantrums can be exhibited in problematic conduct including damaging property or interpersonal aggression in adolescents and youth. Similarly spiteful and resentful behaviors may take the form of callously or deliberately hurting others to get back at them, or it may be characterized as resentful brooding that suggests irritability.

Also, our findings were similar when anxiety and depressive symptoms were considered separately, and hence these were combined into an internalizing variable in this research. Stringaris et al. (2009) also showed that irritability (but not arguing) at age about 14 years was significant in the prediction of several types of internalizing problems including major depressive disorders, generalized anxiety, and dysthymia in at age 20. Further, research on the role of irritability and defiance in sustaining pathology in clinical samples with different subtypes of mood disorders is needed.

In addition, whereas previous research on the ODS sub dimension with children used parent or teacher reports of mental health problems, the current study is based on self-reported symptoms. This may increase the strength of correlations among the constructs due to shared reporter variance. Also given concerns about social desirability, the assessment of irritability, defiance and conduct problems might be strengthened with reports from parents, romantic partners, or peers. However, the data collection procedures were designed to maximize the protection of privacy in the youths’ responses. The reliability of these measures is also supported by their consistent correlations across intervals of 2 years and 4 years. The participants own experiences of internalizing are likely to be most accurate and these are also highly consistent over the two (r=0.62) and 4 year interval (r=0.63). In the transition to young adulthood, youth often move into independent housing and parents may become less aware of ongoing problems. Peer support networks and dating partners also tend to fluctuate over this period and new friends may not be aware of the youth’s experiences of anxiety and depression. Current and previous findings (Leadbeater et al. 2012) of the consistency in the rank ordering of symptom levels (intercepts) in repeated assessments also offers considerable confidence in the reliability and validity of these self-reports. The use of dimensional measures with a community-based sample instead of diagnostic categories of internalizing and externalizing disorders may also diminish the comparability of our findings with previous research.

In addition, our cross-sequential design with cohorts spanning ages 12 to 25 may only approximate a “true” picture of the patterns of change that might be found by following a single age group over time. However, research suggests that comparisons of cross-sequential and true longitudinal designs yield similar results (Duncan, Duncan, and Strycker 2006; Little 2013), and longitudinal research comparing trajectories of, and co-variation in irritability and defiance with mental health symptoms over the transition from adolescence to young adulthood is limited.

Conclusions and Implications

This study expands our understanding of the relations of irritability and defiance with conduct problems and internalizing in adolescence and young adulthood. The distinction between the irritable and defiant symptoms of oppositional defiant disorders offers important targets for the implementation of cognitive behavioral and interpersonally oriented therapies that can address the negative affect and interpersonal conflicts that may both stem from and sustain internalizing and conduct problems over time. Our findings also suggest that improvements in emotion regulation (e.g. managing anger and irritability) and in the quality of interactions in salient relationships (e.g. improving attachments and reducing argumentative defiant interactions) may help to reduce the co-occurrence and spiralling of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Given the stability of these problems in adolescence and their slow average decline in young adulthood, early identification and treatment of these mental health concerns is needed.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aebi MM, Müller UC, Asherson PP, Banaschewski TT, Buitelaar JJ, Ebstein RR, Steinhausen HC. Predictability of oppositional defiant disorder and symptom dimensions in children and adolescents with ADHD combined type. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research In Psychiatry and The Allied Sciences. 2010;40:2089–2100. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beggs DJ, Langley DJ, Williams SM. Validity of self reported crashes and injuries in a longitudinal study of young adults. Injury Prevention. 1999;5:142–144. doi: 10.1136/ip.5.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: A structural equation approach. Wiley Series on probability and mathematical statistics. New Jersey: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo DE, Hofer SM. Assessing factorial invariance in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. In: Ong AD, van Dulmen M, editors. Handbook of methods in positive psychology. Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, Cunningham CE, Georgiades K, Cullen J, Racine Y, Pettingill P. The Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (BCFPI): 2. Usefulness in screening for child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:424–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford S, Rickwood D. Psychosocial assessments for young people: a systematic review examining acceptability, disclosure and engagement, and predictive utility. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2012;3:111–125. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S38442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD. An affective dimension within oppositional defiant disorder symptoms among boys: personality and psychopathology outcomes into early adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:1176–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke J, Loeber R. Oppositional defiant disorder and the explanation of the comorbidity between behavioral disorders and depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17:319–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Hipwell AE, Loeber R. Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder as predictors of depression and conduct disorder in preadolescent girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:484–492. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201005000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CE. Behavioral disorders in girls: A closer look at the epidemiology and development of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. In: Lundberg-Love PK, Nadal KL, Paludi MA, editors. Women and mental disorders. 1–4. Santa Barbara: Praeger/ABC-CLIO; 2012. pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland W, Shanahan L, Costello E, Angold A. Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, Copeland W, Angold A. Trends in psychopathology across the adolescent years: what changes when children become adolescents, and when adolescents become adults? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:1015–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Boyle MH, Hong S, Pettingill P, Bohaychuk D. The Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (BCFPI): 1. Rationale, development, and description of a computerized children’s mental health intake and outcome assessment tool. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:416–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ancos E, Ascaso L. Sex differences in oppositional defiant disorder. Psicothema. 2011;23(4):666–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabick DG, Gadow KD. Deconstructing oppositional defiant disorder: clinic-based evidence for an anger/irritability phenotype. Journal of the American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabick DAG, Ollendick TH, Bubier JL. Co-occurrence of ODD and anxiety: shared risk processes and evidence for a dual-pathway model. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17:307–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. 2. New York: Psychology Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta L, Granero R, de la Osa N, Penelo E, Domènech JM. Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in 3-year-old preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:1128–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:272–299. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Nigg JT. Current issues in the diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. Annual Review Of Clinical Psychology. 2012:877–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadermann AM, Guhn M, Zumbo B. Estimating ordinal reliability for Likert-type and ordinal item response data: A conceptual, empirical, and practical guide. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation. 2012:17. Available online: http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=17&n=3.

- Graber JA, Sontag LM. Internalizing problems during adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol 1: Individual bases of adolescent development. 3. Hoboken: Wiley; 2009. pp. 642–682. [Google Scholar]

- Hames J, Hagan C, Joiner T. Interpersonal processes in depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9:355–377. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell AE, Stepp S, Feng X, Burke J, Battista DR, Loeber R, Keenan K. Impact of oppositional defiant disorder dimensions on the temporal ordering of conduct problems and depression across childhood and adolescence in girls. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:1099–1108. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K. Mind the gap: assessing impairment among children affected by proposed revisions to the diagnostic criteria for oppositional defiant disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:352–359. doi: 10.1037/a0024340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Pardini DA. ODD dimensions, ADHD, and callous–unemotional traits as predictors of treatment response in children with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:713–725. doi: 10.1037/a0020910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger F, Polanczyk G, Goodman R, Rohde L, Graeff-Martins A, Salum G, Stringaris A. Dimensions of oppositionality in a Brazilian community sample: testing the DSM-5 proposal and etiological links. Journal of the American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater B, Kuperminc G, Blatt S, Hertzog C. A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1268–1282. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Thompson K, Gruppuso V. Co-occurring trajectories of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and oppositional defiance from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:719–730. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.694608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little T. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guildford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson HA, Cheavens JS, Fristad MA. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents: theory, treatment adaptations, and empirical outcomes. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2013;16:59–80. doi: 10.1007/s10567-012-0126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti MM, Obsuth I. Effectiveness of an attachment-focused manualized intervention for parents of teens at risk for aggressive behaviour: the connect program. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:1347–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold L, Lundervold A, Manger T. Oppositional defiant disorder—Gender differences in co-occurring symptoms of mental health problems in a general population of children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:577–587. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R, Costello E, Angold A, Copeland WE, Maughan B. Developmental pathways in oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:726–738. doi: 10.1037/a0020798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Clark AG. Conceptions of relationships in children with depressive and aggressive symptoms: social-cognitive distortion or reality? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:41–56. doi: 10.1023/A:1005299429060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankman S, Lewinsohn P, Klein D, Small J, Seeley J, Altman S. Subthreshold conditions as precursors for full syndrome disorders: a 15-year longitudinal study of multiple diagnostic classes. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1485–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R. Longitudinal outcome of youth oppositionality: irritable, headstrong, and hurtful behaviors have distinctive predictions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:404–412. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181984f30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Cohen P, Pine D, Leibenluft E. Adult outcomes of youth irritability: A 20-year prospective community-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1048–1054. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Zavos H, Leibenluft E, Maughan B, Eley TC. Adolescent irritability: phenotypic associations and genetic links with depressed mood. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:47–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Maughan B, Copeland WS, Costello E, Angold A. Irritable mood as a symptom of depression in youth: prevalence, developmental, and clinical correlates in the great smoky mountains study. Journal of the American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:831–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan YM, Stringaris A, Maughan B, Barker ED. Developmental continuity of oppositional defiant disorder subdimensions at ages 8, 10, and 13 years and their distinct psychiatric outcomes at age 16 years. Journal of the American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]