Abstract

Background

Patient satisfaction is often measured using the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) Survey. Our aim was to examine the structural and clinical determinants of satisfaction among inpatients with prolonged lengths of stays (LOS).

Methods

Adult patients who were admitted between 2009 and 2012, had a LOS ≥ 21 days, and completed the HCAHPS survey were included. Univariate analyses assessed the relationship between satisfaction and patient/system variables. Recursive partitioning was used to examine the relative importance of the identified variables.

Results

101 patients met inclusion criteria. The average LOS was 35 days and 58% were admitted to a surgical service. Satisfaction with physician communication was significantly associated with fewer consultations (p<0.01), non-operative admission (p<.001), no ICU stay (p<.01), non-surgical service (p<.01), and non-ER admissions (p=.03). Among these, having fewer consultations had the highest relative importance.

Conclusions

In long stay patients, having fewer inpatient consultations was the strongest predictor of patient satisfaction with physician communication. This suggests that examination of patient-level data in clinically relevant subgroups may be a useful way to identify targets for quality improvement.

Keywords: Patient Satisfaction, HCAHPS, Physician Communication, Surgery Service

Introduction

With the 2001 Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) landmark report Crossing the Quality Chasm, patient-centered care has been prominently emphasized as one of the pillars of high-quality health care.1 Several critical national efforts focused on patient-centered care began, including the establishment of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), and the incorporation of patient satisfaction data, as measured by the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Services (HCAHPS) survey, into the standard metrics used to compare hospital services by the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA) program.

The HCAHPS survey was developed jointly by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) beginning in 2002. After testing, rigorous review and initial implementation by CMS, the first set of national HCAHPS data became publically available in 2008 and accessible on the Hcahpsonline.org website2. Since that time, hospitals have been required to collect HCAHPS data, and the results are now incorporated into patient experience measures used in CMS’ reimbursement formulas.3

Although the broad use of the HCAHPS survey has brought focus to the area of patient satisfaction, the important distinction between a hospital’s HCAHPS survey ranking and its provision of patient-centered care has been blurred.4 As defined by the IOM, patient-centered care is responsive to the needs, values, and expressed preferences of the individual patient.1 It has previously been shown in a study examining 1.2 million HCAHPS survey results, that although adjusted hospital scores measure distinctions in quality for the average patient, there is significant variability in hospital performance when specific patient subgroups are examined.4 This group and others concluded that the best hospitals for most patients are not necessarily the best ones for all patients.5 Further research that examines patient satisfaction for specific patient subgroups is therefore important.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the determinants of patient satisfaction in one such specific subgroup – patients with prolonged lengths of stay (LOS). This subgroup was targeted for detailed analysis because of their unique position amongst inpatients. Patients with prolonged lengths of stay have accumulated an adequate length of hospital experience to provide a more longitudinal assessment of satisfaction. Specifically, they experience some aspects of the structural processes of inpatient care (e.g. transitions in care) that cannot be experienced by those with shorter stays.6,7 Because physician discontinuity and physician communication has previously been shown to negatively impact patient satisfaction, patients with prolonged hospital stays are the best barometers of how these challenges are being met in the inpatient setting. The impact of hospital structural variables, such as continuity of care, on patient satisfaction is best studied by examining the patients who are most impacted by transitions in care. Further, because a prolonged length of stay is a marker of a more complicated hospital course8, studying these patients will allow for identification of specific needs that are different from those of more routine patients with less complex admissions.

Material and Methods

Patients

Using institutional hospital administrative data at the University of Wisconsin, adult patients admitted between July 1st 2009 and June 30th 2012 with a hospital stay of ≥21 days were identified. Only patients with completed satisfaction surveys, both standard HCAHPS and institutional Press Ganey surveys, were included. Standard HCAHPS exclusions applied (e.g. patients admitted for rehabilitation or psychiatric care, prisoners, those discharged to skilled nursing facilities or hospice, and those that have received a survey within 90 days).

A retrospective detailed chart review extracted clinical and structural variables. Patient variables included demographics, diagnosis, comorbidities, self-reported health status, educational level and cognitive functioning at discharge. Medical care variables included admitting diagnosis, LOS, admission route, level of care, invasive procedures, transfusion, and advanced imaging studies. Variables examining the inpatient structural processes were also collected and included admitting service, service transfers, physician coverage model, number of attending providers on primary service, number of consulting services, and continuity of consulting attending providers. Consulting services included only typical medical and surgical services and not ancillary consultative services, such as interpreter services, chaplain services, physical or occupational therapy, or social work/case management services. Other physician consulting services that were included were pain management, surgical nutrition, psychiatry, rehab medicine interventional radiology and palliative care. For the purpose of analysis, each referral to a consulting service involved in a patient’s care during an admission was recorded as one referral even if the consulting service was involved multiple times during the admission. Discharge variables were also gathered including discharge location, discharge needs, and need for readmission within thirty days of discharge. Clinical data were collected prior to analysis of the satisfaction data, so as to avoid the potential for collection bias. The Institutional Review Board approved the study prior to its inception.

Survey

The standard HCAHPS survey consisting of 32 questions9 was administered by a third party vendor. Our institutional survey response rate over the time period of the study was 32.4%. For the purpose of this study, outcome measures included only global measures of satisfaction with physicians and the hospital. Domains such as communication with nurses, medications, pain management, discharge information, and hospital environmental factors were not examined. Physician satisfaction was measured using the standard communication composite which includes three questions. These include: “During this hospital stay, how often did doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?”; “During this hospital stay, how often did doctors listen carefully to you?”; “During this hospital stay, how often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand?” All of these questions have the following possible choices: 1 – Never, 2 – Sometimes, 3 – Usually, 4 – Always. As our study was focused on analysis at the patient level, a physician composite was constructed by dividing patients into two groups, the group that answered “always” for all three communication questions and those that had any other combination of responses. Specifically, the numeric responses for all of the three component questions were summed and only those with “always” responses to all three (for a total score of 12) were designated top box for the physician composite. The overall hospital satisfaction was determined using the HCAHPS survey question, “Using any number from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst hospital possible and 10 is the best hospital possible, what number would you use to rate this hospital during your stay?” Responses 9 and 10 were considered top box.10 In order to assure the validity of the HCAHPS responses in this patient subgroup, we only examined those patients who also had the full complement of satisfaction data available.

Summary measures of satisfaction from a hospital specific Press Ganey survey were then used as separate outcome measures. The predictors of satisfaction were largely concordant with those of the HCAHPS summary measures and therefore these data are not presented.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were generated for demographics and clinical characteristics. Univariate analyses were performed to assess the relationship between the outcome of satisfaction, demographics and structural variables. Chi-squared test or Student’s t-test was used to make the statistical comparisons as appropriate. Further Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to quantify the strength of association between variables. The ability of a group of factors to predict satisfaction versus non-satisfaction in our dataset was assessed through the use of recursive partitioning method in a random forests (RF) framework.11 The variable “importance” was evaluated via mean decrease in accuracy when that variable was added to the model. This method was chosen, instead of multivariable regression, because the extent of collinearity and the large number of significant variables relative to the sample size. Further, because tree-based methods, such as random forests, provide an assessment of variable importance which reflects both the main effect and the variable interactions, it is well suited to variables with complex interactions, where parametric methods are more limited.12 Variables with a large measure are better for classification of the data and hence higher impact on satisfaction. Only variables with p-value < .10 were included in the random forests analysis. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) software. Analysis of RF was done using random forest package in R.11,13 A p-value ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant for two-tailed tests.

Results

Patient Characteristics

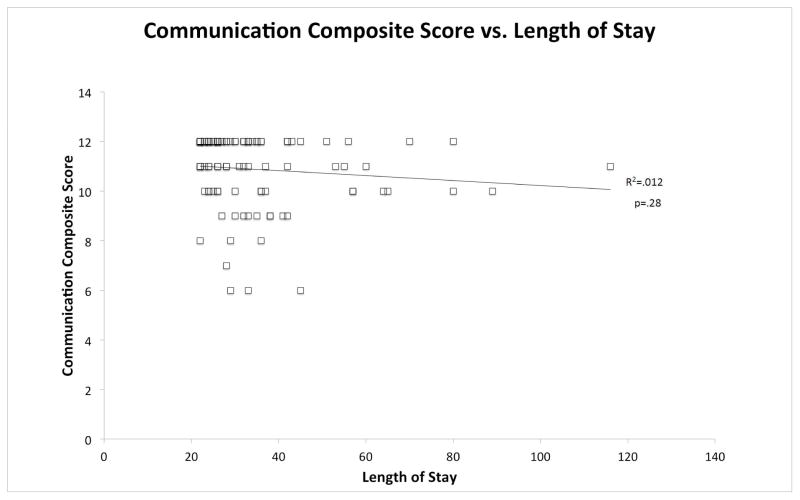

Our sample identified 101 patients with the following demographic information: 44.8% female, 58.1% married, and a mean age of 56.5 ±13.9 years (Table 1). The mean LOS was 34.8 ±15.8 days. Although the inclusion criteria mandated a minimum stay of 21 days, there was a wide range in LOS (Figure 1). A total of 58.1% of patients were admitted to a surgical service, 62.9% had an operation, and 55.2% stayed at least one day in the intensive care unit (ICU). The mean number of attending physicians on the primary service over the entire length of stay was 4.5 ±2.3 days, and 41% of patients had a change in the assignment of primary service (exclusive of those transfers into and out of the ICU). The mean number of consulting services was 3.9 ±2.8, with a mean number of consulting attending physicians over the entire length of stay of 7.3 ±6.7. Fifty-eight percent of consultations were conducted by medical services (e.g. 9% by infectious disease, 7% by cardiology, 6 % by endocrine/ diabetes management and 4 % by nephrology). Surgical services accounted for 17% of the total consultations (e.g. 5% by general surgery, 3 % by trauma surgery and 2 % plastic surgery) and the remaining fraction, 25%, were from other physician consultations (e.g. 5% by rehab medicine, 7% by surgical nutrition, 5% by rehab medicine, 2% by psychiatry and 1% by palliative care).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with a Hospital Stay of ≥ 21 Days

| Demographic Characteristics (N=101) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 56.5 (13.9) | |

| Female (%) | 44.8% | |

| Caucasian (%) | 97.1% | |

| Married (%) | 58.1% | |

| Educational Level (n=24)a | 8th grade or less | 0 |

| Some high school | 0 | |

| High school graduate | 11 | |

| Some College | 8 | |

| 4 year college degree | 3 | |

| More than 4 years | 2 | |

| Self-Reported Health Status (n=24)a | Excellent | 1 |

| Very Good | 7 | |

| Good | 8 | |

| Fair | 7 | |

| Poor | 1 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.7) | |

| Comorbidities (%) | Diabetes | 21.8% |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 22.8% | |

| Hypertension | 28.7% | |

| Psychiatric Illness | 19.8% | |

| Hematologic Cancers | 25.7% | |

| Solid Tumors | 13.9% | |

| Structural Characteristics (N=101) | ||

| Admission Route (%) | Planned Admission | 38.1% |

| Direct Admission | 37.1% | |

| Emergency Department | 18.1% | |

| Clinic | 6.7% | |

| Admission Service (%) | Medicine Subspecialty | 29.5% |

| SICU | 15.2% | |

| Neurosurgery | 9.5% | |

| General Surgery | 8.6% | |

| Others | 37.2% | |

| Change in Primary Services from Admission (%) | 41.0% | |

| ICU Stay (%) | 55.2% | |

| Length of Stay, mean (SD) | 34.8 (15.8) | |

| Surgical Procedure (%) | 62.9% | |

| Admission to a Surgical Service (%) | 58.1% | |

| Attending Physicians Primary Service, mean (SD) | 4.5 (2.3) | |

| Had ≥ 1 Consultation (%) | 88.6% | |

| Number of Consulting Services, mean (SD) | 3.9 (2.8) | |

| Number of Consulting Physicians, mean (SD) | 7.3 (6.7) | |

| Number of Concurrent Consulting Services, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.7) | |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation

Data only available for 24 of 101 subjects

Figure 1. Distribution of Length of Stays.

Frequency of Hospital Length of Stay by Days

Group Characteristics

Overall during this time period, the HCAHPS response rate was 32.4%. The specific response rate in this subset is not known, but it is likely that many patients with prolonged stays were discharged to rehab or skilled nursing facilities and therefore were subject to the standard exclusion for HCAHPS survey administration. Of 101 patients, only 50% (n=50) rated their physician as top box in the communication composite. The percentage of top box responses for the individual questions of the composite are as follows: 1). “During this hospital stay, how often did doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?” (80.4% top box); 2). “During this hospital stay, how often did doctors listen carefully to you?” (67.7% top box); 3). “During this hospital stay, how often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand?” (54.5% top box).

When patients who scored their physician as top box were compared to those who did not, the groups were similar demographically (Table 2). There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to age, gender distribution, marital status, self-reported health status, educational level, or race. Patients in both groups had similar comorbidity severity as measured by Charlson Comorbidity Index14 and when examined by individual comorbid conditions. Similarly, there were no differences in demographic variables for those patients who gave a top box rating to the overall hospital stay when compared to those who did not (data not shown). Responses for overall hospital rating were top box in 75% of completed surveys.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics Comparison between Top box Physician Composite and Lower Physician Ratings

| Demographic Characteristics | Physician Composite Top box (n=50) | Physician Composite Not Top box (n=51) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 55.9 (12.8) | 57.2 (15.4) | .65 |

| Female (%) | 52.0% | 37.3% | .15 |

| Caucasian (%) | 96.0% | 98.0% | .32 |

| Married (%) | 50.0% | 58.8% | .90 |

| Educational Level (n=24)a | |||

| 1 – 8th grade or less | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 - Some high school | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 - High school graduate | 8 | 3 | .17 |

| 4 - Some College | 3 | 5 | |

| 5 – 4 year college degree | 2 | 1 | |

| 6 - More than 4 year | 0 | 2 | |

| Self-Reported Health Status (n=24)a | |||

| Excellent | 1 | 0 | |

| Very Good | 6 | 1 | |

| Good | 4 | 4 | .15 |

| Fair | 2 | 5 | |

| Poor | 0 | 1 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation

Data only available for 24 of 101 subjects

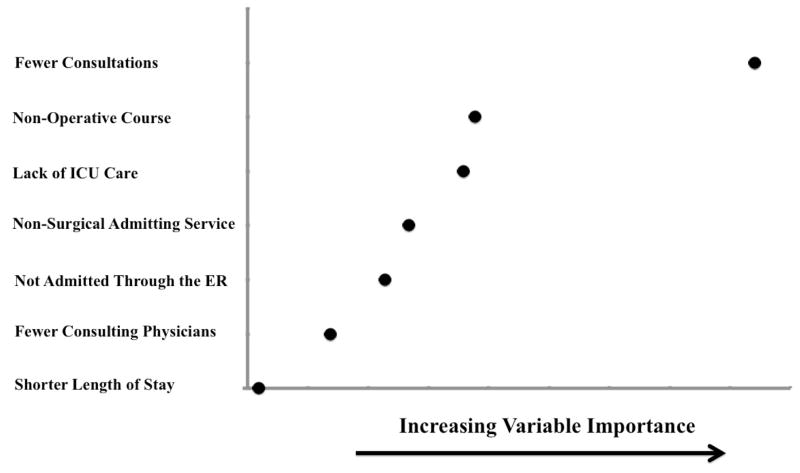

Factors Important for Physician and Hospital Satisfaction

On univariate analyses examining the structural facets of care which were associated with top box responses for physician communication, the following were significantly associated: fewer consultations (p<.01), non-operative admission (p<.001), admission without an ICU stay (p<.01), nonsurgical admitting service (p<.01), shorter length of stay (p=.03), and non-emergency room admission routes (p=.03; Table 3A). The number of attending physicians on the primary service and number of services consulting concurrently were not significantly associated with top box scores for physician communication. We similarly examined factors that were associated with overall satisfaction with the hospital. When examining associations with top box hospital ratings, fewer consultations was the only variable significantly associated with overall hospital satisfaction [3.65 ±2.9consultations (top box) vs. 4.92 ±2.5 consultations (not top box), p=.05].

Table 3A.

Association of Hospital Structural Characteristics with Patient Satisfaction Scores for Physician Communication

| Structural Variables | Physician Composite Top box (n=50) | Physician Composite Not top box (n=51) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Consulting Services, mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.3) | 4.6 (2.5) | <.01 |

| Operation This Admission (%) | 48% | 80% | <.001 |

| ICU Admission (%) | 38% | 71% | <.01 |

| Surgical Service at Admission (%) | 44% | 73% | <.01 |

| Admission Through ED (%) | 10% | 27% | .03 |

| Length of Stay, mean days (SD) | 31 (12) | 38 (19) | .03 |

| Number of Consulting Physicians, mean (SD) | 6.0 (7.1) | 8.6 (6.1) | .05 |

| Number of Attending Physicians on Primary Service, mean (SD) | 4.3 (2.6) | 4.6 (2.0) | .43 |

| Service Change, mean (SD) | 0.7 (1.6) | 1.0 (1.3) | .30 |

| Number of Concurrent Consulting Services, mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.8) | 2.4 (1.4) | .20 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; NS, not significant; ED, Emergency Department

Factors Important for Physician Satisfaction in Surgical Patients

The 65 patients who underwent an operation were then examined separately, in order to determine if long stay surgical patients were similar to the larger population (Table 3B). Again the demographic variables were similar between these groups. The same predictors were compared between top box and not top box groups. Similar trends existed for all variables, although given the sample size, these were not statistically significant differences. These factors were also examined using the recursive partitioning method in a random forests framework, and similar to the larger population, fewer consultations again was the strongest predictor of patient-reported satisfaction with physician communication (data not shown).

Table 3B.

Association of Hospital Structural Characteristics with Patient Satisfaction Scores for Physician Communication for Surgical Patients Only

| Structural Variables | Physician Composite Top box (n=24) | Physician Composite Not top box (n=41) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Consulting Services (mean± SD) | 4.6±2.5 | 5.1±2.0 | 0.53 |

| ICU Admission (%) | 63% | 83% | 0.07 |

| Surgical Service at Admission (%) | 83% | 88% | 0.61 |

| Admit Through ED (%) | 13% | 27% | 0.21 |

| Length of Stay (mean days ± SD) | 33±15 | 39±20 | 0.24 |

| Number of Consulting Physicians (mean ± SD) | 9.4±7.5 | 9.4±5.4 | 1.0 |

| Number of Attending Physicians on Primary Service (mean ± SD) | 4.8±3.6 | 4.7±2.0 | 0.85 |

| Service Change (mean ± SD) | 1.2±1.9 | 1.2±1.4 | 0.98 |

| Number of Concurrent Consulting Services(mean ± SD) | 2.8±1.5 | 2.6±1.1 | 0.35 |

Discussion and Conclusions

Patients with prolonged LOS represent an important subgroup when examining patient satisfaction. Although long stay patients in our study have satisfaction with the hospital that is similar to that of the general population, they have significantly lower satisfaction with physician communication than those with more routine LOS.15 The most significant factor associated with satisfaction in patients with prolonged LOS, with both the hospital and physician communication, was having fewer consultative services over the course of the hospitalization. This is a finding is novel and to our knowledge, has not previously been described in the literature.

Inpatient consultation is a frequent event particularly in tertiary academic centers.16 In our patient population, 89% of patients had at least one consultation. We found a mean of four consulting services with seven separate consulting staff physicians per patient over the hospitalization. Multiple reports in the literature document the ability of subspecialty inpatient consultation teams to impact treatment plans and outcomes.17–21 However, the impact of consultative services on inpatient satisfaction has not previously been examined. Our finding of a strong and negative impact of number of consultations on patient satisfaction with both the hospital and physician communication is therefore of interest.

Although our study reveals an association between fewer consultations and higher patient satisfaction, a causal relationship is not clearly established and the mechanism underlying this relationship is not evaluated in this study. However, several reports in the literature detail the difficulties inpatient physicians have with consulting services16,22 and perhaps explain some factors underlying this association. Physicians identify difficulties with consulting providers having lower investment in the case, demonstrating unprofessional behaviors, and providing conflicting information to the patient.22 Similarly, consultative teams with conflicting views on prognosis or treatment can add to the confusion for a patient with critical illness.16,22 Previous reports using care delivery teams may suggest a framework for other types of inpatient consultations.23 These studies have emphasized a collaborative practice environment that involves communities of practice working together in an orchestrated fashion. Taken together, this information suggests that it may not be the consultations themselves that negatively affected patient satisfaction, but perhaps the disjointed care environment resulting from multiple treating clinician groups without an integrated system that lowers satisfaction.

Another important finding is lower levels of satisfaction for patients requiring an operation or admission to a surgical service. However, surgical patients nationally rate communication with physicians more highly than their medical or obstetrical counterparts,24 which is in keeping with the findings at our institution (data not shown). Lower satisfaction levels in long-stay patients who have undergone surgery is therefore surprising, but highlights the importance of examining clinically relevant subgroups before extrapolating satisfaction data more generally.4 Similar to other studies, we found that other characteristics of complex surgical patients were also associated with worse satisfaction. Specifically, patients admitted through the emergency department and those who required intensive care had lower satisfaction. 25,26 These types of findings have previously raised concern about the applicability of standard HCAHPS survey questions for surgical patients, as surgical hospital care may be fundamentally different from medical care. The recent development of the Surgical HCAHPS (S-CAHPS) is a step forward in assessment of patient satisfaction27–29 and will hopefully allow further study of the factors unique to patient satisfaction in surgical patients.

The relationship of hospital LOS to satisfaction has been examined in a number of reports, but with conflicting results. One French study demonstrated that those with shorter LOS have higher satisfaction with some dimensions,30 but this has not been convincingly demonstrated using HCAHPS survey data in the U.S. One difficulty with examining LOS relative to satisfaction is that it is unlikely to be a simple relationship that can be examined as a continuous variable. When grouped into relevant categories by hospital LOS, patient satisfaction has been shown to have unique predictors in each group.31 Further, as shown in this and another study, hospital LOS may have differing effects on satisfaction with the hospital and physician communication.32 Our finding that there was no correlation between LOS and satisfaction in patients with stays ≥ 21 days is therefore a useful addition to the literature.

Although this study has the marked advantage of combining patient-level satisfaction data with detailed clinical data, limitations remain. First, because the HCAHPS survey is not administered to patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities, this important group (many of whom have prolonged hospital stays) is not included in our analysis. Second, because we were interested in the structural characteristics of inpatient care provided by physicians, we chose to use as our outcome measure satisfaction with the hospital and with physician communication. Other relevant domains that influence overall satisfaction, such as communication with nurses33 were not examined herein but are ripe for future study. The demographic homogeneity of our population and setting of a single academic medical center somewhat limit generalizability. Because detailed clinical and structural hospital variables (such as consultations and transitions in care) cannot be examined without labor-intensive detailed chart review, multicenter datasets are simply not currently available. This study is therefore hypothesis generating and confirmation of its finding with other institutional datasets would be useful. In order to better understand the experience of long-stay patients, qualitative studies are needed to examine the specific drivers of dissatisfaction so that quality improvement efforts can be most effectively studied and implemented.

In conclusion, the use of aggregated hospital-level HCAHPS survey data cannot substitute for the assessment of healthcare by individual patients with a variety of needs, values and preferences. The importance of evaluating patient subgroups such as those with prolonged hospital stays has been demonstrated by the novel findings of this study. Further research in other clinically relevant subsets is needed to best inform the implementation of quality improvement efforts.

Figure 2. Variable Importance for Top box Physician Communication Composite Score.

Variables of Increasing Importance Related to the Physician Communication Score

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Wisconsin Surgical Outcomes Research Program (WiSOR) for manuscript review.

Funding/Support

Dr. Schmocker received funding support from NIH grant number T32-5T32CA090217-12. This grant assisted in funding Dr. Schmocker’s time to work on this project.

Footnotes

Ethical approval

Authors Ryan K Schmocker, M.D. and Emily R. Winslow, M.D. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Previous presentations

Information included in this manuscript was presented on February 4, 2011 at the 2014 Academic Surgical Congress in San Diego, CA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Council NR. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washngton DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Summary of HCAHPS Survey Results. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS); 2008. [Accessed July 17, 2014]. at http://www.hcahpsonline.org/Executive_Insight/files/Final-State%20and%20National%20Avg-March%20Report%208-20-2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Accessed August 18, 2013];The Official Website for the Medicare Hospital Value-based Purchasing Program. 2013 at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-basedpurchasing/index.html?redirect=/hospital-value-based-purchasing.

- 4.Elliott MN, Lehrman WG, Goldstein E, et al. Do hospitals rank differently on HCAHPS for different patient subgroups? Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67:56–73. doi: 10.1177/1077558709339066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker ER, Hockenberry JM, Bae J, et al. Factors in patients’ experience of hospital care: Evidence from California, 2009–2011. Patient Experience Journal. 2014;1:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner J, Hansen L, Hinami K, et al. The impact of hospitalist discontinuity on hospital cost, readmissions, and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1004–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2754-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saultz JW, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Annals of family medicine. 2004;2:445–51. doi: 10.1370/afm.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horn SD, Sharkey PD, Buckle JM, et al. The relationship between severity of illness and hospital length of stay and mortality. Med Care. 1991;29:305–17. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199104000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.HCAHPS Fact Sheet (CAHPS Hospital Survey) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS); 2013. [Accessed July 15, 2014]. at http://www.hcahpsonline.org/files/August%202013%20HCAHPS%20Fact%20Sheet2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calculation of HCAHPS Scores: From Raw Data to Publicly Reported Results. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2012. [Accessed May 20, 2014]. at http://www.hcahpsonline.org/Files/Calculation%20of%20HCAHPS%20Scores.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breiman L. Random Forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strobl C, Malley J, Tutz G. An introduction to recursive partitioning: rationale, application, and characteristics of classification and regression trees, bagging, and random forests. Psychological methods. 2009;14:323–48. doi: 10.1037/a0016973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News. 2002;2:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmocker R, Vang X, Cherney Stafford L, et al. Involvement of a Surgical Service Improves Patient Satisfaction in Patients Admitted with Small Bowel Obstruction. Am J Surg. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.11.010. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan MR, Conley J, Ghali WA. Consultation patterns and clinical correlates of consultation in a tertiary care setting. BMC research notes. 2008;1:96. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-1-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477–82. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2440-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granwehr BP, Kontoyiannis DP. The impact of infectious diseases consultation on oncology practice. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:353–9. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283622c32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.England RW, Ho TC, Napoli DC, Quinn JM. Inpatient consultation of allergy/immunology in a tertiary care setting. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90:393–7. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61822-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta RL, McDonald B, Gabbai F, et al. Nephrology consultation in acute renal failure: does timing matter? Am J Med. 2002;113:456–61. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Douglas MR, Peake D, Sturman SG, et al. The inpatient neurology consultation service: value and cost. Clinical medicine (London, England) 2011;11:215–7. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.11-3-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens JP, Johansson AC, Schonberg MA, Howell MD. Elements of a high-quality inpatient consultation in the intensive care unit. A qualitative study. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2013;10:220–7. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201212-120OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makowsky MJ, Schindel TJ, Rosenthal M, et al. Collaboration between pharmacists, physicians and nurse practitioners: a qualitative investigation of working relationships in the inpatient medical setting. Journal of interprofessional care. 2009;23:169–84. doi: 10.1080/13561820802602552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patient-Mix Coefficients for April 2014 Publicly Reported HCAHPS Results. [Accessed June 1, 2014];Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. 2014 at http://www.hcahpsonline.org/files/Coefficients_April_2014_PublicReporting_12_19_2013.pdf.

- 25.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Franks P. Influence of elective versus emergent hospital admission on patient satisfaction. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 2014;27:249–57. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.130177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hargraves JL, Wilson IB, Zaslavsky A, et al. Adjusting for patient characteristics when analyzing reports from patients about hospital care. Med Care. 2001;39:635–41. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200106000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenberg CC, Kennedy GD. Advancing quality measurement to include the patient perspective. Ann Surg. 2014;260:10–2. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz KA, Rhee JS, Brereton JM, et al. Consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems surgical care survey: benefits and challenges. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:671–7. doi: 10.1177/0194599812452834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sage J. Using S-CAHPS. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2013;98:53–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thi PLN, Briancon S, Empereur F, Guillemin F. Factors determining inpatient satisfaction with care. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:493–504. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tokunaga J, Imanaka Y. Influence of length of stay on patient satisfaction with hospital care in Japan. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14:493–502. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/14.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kebede S, Shihab HM, Berger ZD, et al. Patients’ Understanding of Their Hospitalizations and Association With Satisfaction. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174:1698–700. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, et al. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]