Abstract

In mammals, the master transcription regulator of antioxidant defences is provided by the Nrf2 protein. Phylogenetic analyses of Nrf2 sequences are used here to derive a molecular clock that manifests persuasive evidence that Nrf2 orthologues emerged, and then diverged, at two time points that correlate with well-established geochemical and palaeobiological chronologies during progression of the ‘Great Oxygenation Event’. We demonstrate that orthologues of Nrf2 first appeared in fungi around 1.5 Ga during the Paleoproterozoic when photosynthetic oxygen was being absorbed into the oceans. A subsequent significant divergence in Nrf2 is seen during the split between fungi and the Metazoa approximately 1.0–1.2 Ga, at a time when oceanic ventilation released free oxygen to the atmosphere, but with most being absorbed by methane oxidation and oxidative weathering of land surfaces until approximately 800 Ma. Atmospheric oxygen levels thereafter accumulated giving rise to metazoan success known as the Cambrian explosion commencing at ~541 Ma. Atmospheric O2 levels then rose in the mid Paleozoic (359–252 Ma), and Nrf2 diverged once again at the division between mammals and non-mammalian vertebrates during the Permian-Triassic boundary (~252 Ma). Understanding Nrf2 evolution as an effective antioxidant response may have repercussions for improved human health.

The ‘Great Oxygenation Event’ (GOE), at 2.45–1.85 Ga is recognised as the most geologically critical environmental change impacting the history of life on Earth1. Oxygen-producing photosynthetic cyanobacteria appeared much earlier, preceding the increase of atmospheric oxygen marked by the onset of the GOE2, but this oxygen was removed from the atmosphere by rapid oxidation of reduced minerals, precipitating especially vast deposits of ferric oxide from the oxidation of dissolved oceanic ferrous iron. Only after this mineral oxygen sink approached saturation, a process colloquially referred to as the ‘Rusting of the Earth’, did atmospheric oxygen increase at the advent of the GOE, giving a time-lag from the origin of oxygen-producing photosynthetic cyanobacteria that seems to have lasted ~1 Ga1. The GOE provided biologically useable molecular oxygen necessary for aerobic respiration, a decidedly more efficient energy-generating process than pre-existing metabolic pathways, thus setting the stage for an evolutionary transition to the aerobe-dominated biota that continues to this day.

An important problem key to the success of the history of aerobic life on Earth is how cellular processes co-adapted to overcome the metabolic toxicity that results from use of highly reactive molecular oxygen. In aerobic respiration, enzyme catalysed four-electron reduction of oxygen is considered to be a relatively safe process producing water at the terminal end of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. The reductive environment of cells, however, provides ample opportunities for oxygen to undergo successive non-enzymatic univalent reduction, these processes being exacerbated by electrophilic xenobiotics and abiotic agents such as solar ultra-violet radiation. Oxidative stress is the net outcome of oxidative damage to biologically important molecules such as proteins, lipids, carbohydrates and nucleic acids caused by the generation of these reactive oxygen species (ROS). To survive in such a reactive oxygen environment, living organisms produce or sequester a variety of water- and lipid-soluble antioxidant compounds such as vitamins C and E. Oxygen metabolising organisms additionally produce an arsenal of antioxidant enzymes that inactivate ROS. Animal genomes often express over 200 antioxidant and xenobiotic detoxifying enzymes3. The regulated induction and expression of these genes to protect against metabolically induced oxidative stress and electrophilic toxicity is co-ordinated by a small number of related nuclear transcription factors of the bZip/CNC family of proteins, the most important of these being the master regulator, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). The Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) forms an anchor complex with Nrf2. This complex dissociates in response to ROS and toxic electrophiles, thereby releasing Nrf2 which then binds to the nuclear antioxidant response element (ARE) and co-ordinates transcription of multiple antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes4.

The domain architecture of Nrf2 is highly conserved across many diverse species of aerobic organisms. Our previous phylogenetic analyses clearly revealed that, whilst absent in bacteria, archaea and plants, the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway predates the fungal–metazoan divergence5. Here we present a ‘molecular clock’ which estimates that the evolutionary origins of Nrf2 is allied to the timing of the global transition from anaerobic to aerobic conditions, and provides first demonstration of a metabolic adaptation in multiple eukaryotic ancestors having evolved a significant molecular response to the GOE.

Results and Discussion

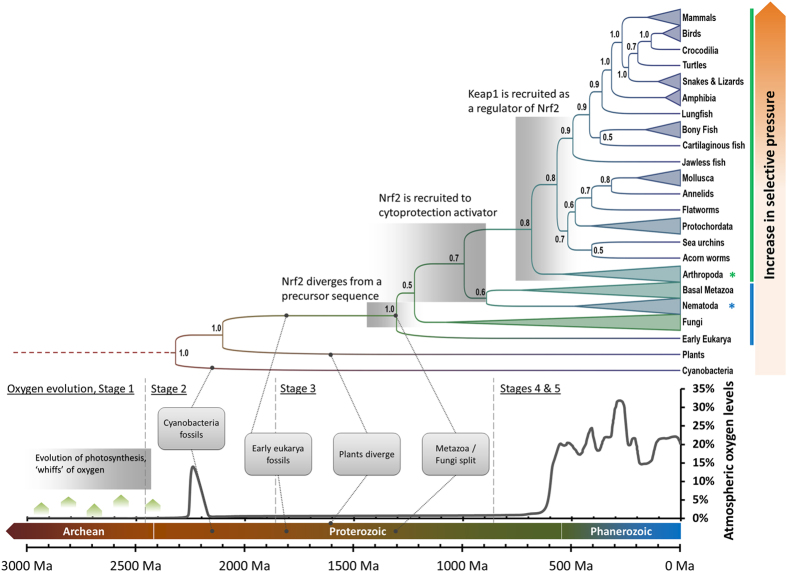

In order to reconstruct the evolutionary life history of Nrf2 in response to mounting oxidative stress, a Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Nrf2 sequences retrieved from the genome sequences of many diverse taxa was performed together with a prediction of evolutionary pressure as evinced by a calculation of synonymous to non-synonymous nucleotide base substitution rates. The results are presented as a phylogenetic tree which was converted to a ‘molecular clock’ using widely accepted paleontological estimates for known splits between major animal phyla. The molecular clock was calibrated based on best paleontological estimates for the divergence of major phyla using compiled data from previous studies, reflecting the very recent hypothesis of Hedges et al. (2015) that speciation is independent of adaptation6,7. The resulting phylogenetic reconstruction was mapped against the changing level of atmospheric oxygen over geological time–with the Phanerozoic oxygen levels taken as a composite of the data afforded from the GEOCARBSULF model of Berner8,9,10, the glaciation-linked oxygen rise models of Harada et al.11 and a compilation of other data1,12,13,14,15. It should be noted that the oxygen curve presented in Fig. 1 is based on “best estimates” and should thus be considered semi-quantitative. While Phanerozoic oxygen trends are well established8,9,10, with moderate error margin9, there is still a level of uncertainty over Proterozoic oxygen estimates. Specifically, the estimated date of origin of photosynthesis ranges from 2,400 to 3,000 Ma15,16,17 and the exact oxygen levels over the majority of the Proterozoic era are subject to controversy18,19,20, as are oxygen level dynamics during the Ediacaran era11,14,21. Thus, while future research might lead to fine tuning of the oxygen level data, the pattern of change presented in Fig. 1 is considered reliable as regards the major trends in oxygen change over geological time.

Figure 1. displays the Nrf2 phylogenetic tree relative to atmospheric oxygen levels during the latter period of Earth’s history.

The chart presents the traditional “5-stage model” of oxygen evolution constructed from compiled data1,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, with the trend line representing a “best guess” model; Stage 1 represents a period when the atmosphere and oceans were largely anoxic; Stage 2 commences the ‘Great Oxygenation Event’; Stage 3 is the period during which atmospheric oxygen levels remained low due to continued absorption by the oceans and oxidative weathering of the terrestrial crust; Stage 4 is the period after saturation of global oxygen buffers, during which oxygen levels rise towards present (Stage 5) atmospheric levels (PAL). The Earth timeline and major geological periods43 are compiled and coloured by age. Eukarya and cyanobacteria appearances are noted according to first confirmed fossil evidence17. Proposed time frames are shown for major Nrf2 divergence and recruitment events. Taxa known or predicted to contain the Keap1-Nrf2 signalling pathway are denoted by the vertical green bar, while taxa containing Nrf2 only (without Keap1) are denoted in blue. Invertebrates with an experimentally validated Nrf2 system are marked with a star (*). Evolutionary pressure increases towards more recently evolved phyla as schematically shown by an increasing orange hue in the selective pressure bar (decrease in dN-dS test statistic and decrease in p-value for null hypothesis of neutral evolution).

The results presented in Fig. 1 allow inference of Nrf2 emergence and sequence diversification as speciation occurred and oxidative stress increased due to changes in atmospheric oxygen. These data would strongly suggest, therefore, that Nrf2 first appeared having evolved from an early eukaryotic peptide that contained a bZIP/CNC domain sequence in Stage 3 of atmospheric oxygenation during the mid-Proterozoic when oxygen was released into the atmosphere but was rapidly absorbed into the Earth’s ocean sediments and terrestrial crust13. The divergence of cyanobacterial Nrf2-like sequences, which we use as an out-group in our evolutionary tree (Fig. 1), differ in evolutionary time from the expected eukaryote-plant divergence (1500 Ma)6, placing plant Nrf2-like sequences closer to cyanobacterial sequences rather than those of early eukaryotes. This significant difference in the bZip/CNC domain architecture of plants is consistent with a lack of nuclear Nrf2-like activation in the response of plants to oxidative stress22 and absence of detectable homology to the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in plant genomes5. Perhaps Nrf2-like sequences in plants might be explained by horizontal transfer during early endosymbiosis, assuming such sequences were inherited from a cyanobacterial precursor of the plant chloroplast23. Interestingly, the predicted oxygen level spike during Stage 2 of atmospheric oxygenation during the mid-Paleoproterozoic period does not seem associated with Nrf2 evolution (as evidenced by the lack of Nrf2 homology in cyanobacteria and plants5) and instead points to an Nrf2-like mechanism as a Metazoan adaptation.

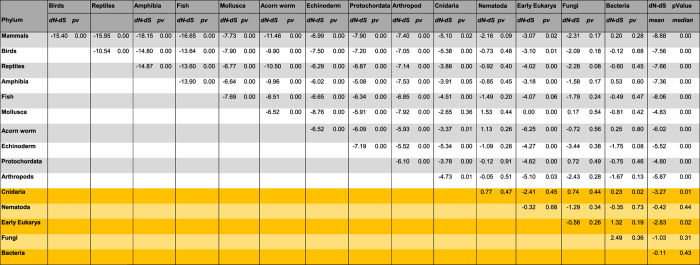

Evolutionary pressure determined by the Codon-based Z-test of selection on both nucleotide and amino acid sequences24 (Fig. 2) reveals strong purifying selection of Nrf2 sequences for all bilateral animals (all p-values ≤ 10−3) with the exception of nematode worms. Cnidaria and other basal metazoans display limited evidence for negative selection (p-values of all tests fall between 0.01 and 0.10). Nematodes and non-metazoan Nrf2 sequences exhibit no significant evidence for selective pressure (p-values of tests are >0.10, as displayed in Fig. 2). Regulation of the Nrf2 antioxidant response exists in simple invertebrates as demonstrated empirically for Caenorhabditis elegans. The Nrf2 homolog SKN-1 in C. elegans, although serving a similar function, has significant differences in structure and regulatory pathways25,26, lacking also a regulatory Keap1 interaction that is present in Drosophila melanogaster27. Notably, the SKN-1 sequence of C. elegans is closer to the homolog sequences of basal metazoans such as cnidarians, indicating that recruitment occurred prior to the metazoan radiation of the Cambrian Explosion. This time frame matches the transition from Stage 3 and the start of Stage 4 of atmosphere oxygenation during which oxygen absorbing buffers in the Earth’s oceans and crust were reaching saturation and atmospheric oxygen levels began to rise1. This rise in atmospheric and ocean oxygen levels led to an increase in aerobic metabolic stress causing evolutionary pressure towards the expansion of antioxidant response systems in animals. Tests for selective pressure indicate that Nrf2 sequences of basal metazoans were under limiting selective pressure, with averaged p-values for evolution neutrality >1 (testing H0: dN = dS, Fig. 2). According to empirical evidence gained from Drosophila melanogaster27,28, genomic Keap1 recruitment occurred in early invertebrates preceding the divergence of the class Insecta after the Cambrian Explosion. This time frame coincides with rising levels of atmospheric O2 during Stage 4 of the Earth’s oxygenation and matches the increased evolutionary pressure (measured by Codon-based Z-test of selection, Fig. 2) detected in Nrf2 sequences from taxa of the early Bilateria. Together, these lines of evidence suggest that rising levels of oxygen led to recruitment of Keap1 for enhanced regulation of Nrf2 for the transcription of cytoprotective genes in the response of animals to oxidative stress.

Figure 2. Displays the Codon-based Z test of selection matrix performed on 42 DNA sequences of Nrf2 homologs from major eukaryotic phyla with cyanobacterial sequence used as outgroup (plant outgroup sequences could not be aligned with the dataset).

Analyses were conducted using the Nei-Gojobori method, and results are grouped by major eukaryotic phyla with the phylum dN-dS value calculated as the mean of group members. All positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated. There were a total of 352 positions in the final dataset and fewer than 5% alignment gaps, missing data, and ambiguous bases were allowed at any position. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6. Figure 2 shows dN-dS and the p-value for null hypothesis of strict neutrality (dN = dS) for each pair of phyla. Phyla likely to have lower selective pressure compared to vertebrates (median P-value >10−3) are highlighted in yellow. Phyla without selective pressure (based on a p-value of 0.05 as the significance threshold) are highlighted in orange. Codon-based Z test of selection matrix.

It is unclear whether fungi and early diverging metazoans possessed a one-protein (Nrf2 only) or two protein (Keap1-Nrf2) antioxidant response system. Nematodes having only a Nrf2-like sequence26,29 are grouped with basal metazoans suggesting a one-protein system that likely evolved early in metazoan development. The position of nematode Nrf2-like sequences, however, differs from what would be expected from the generally accepted Tree of Life in which nematodes belong to a clade of ‘moulting animals’ along with arthropods and several smaller phyla30. The nematode Nrf2-like sequence SKN-1 also has a lower selective pressure (as measured by Codon-based Z-test of selection, Fig. 2) than the Nrf2 of most animals. Such, an alternative explanation is that recruitment of Keap1 had occurred shortly after Nrf2 evolution into an antioxidant response regulatory system at a time close to the animal-fungal divergence at late Stage 3 of atmospheric oxygenation. Homologous Keap1 proteins of nematodes may have subsequently lost persistence of regulatory control over Nrf2-like function in nematodes, perhaps due to a lack of environmental selective pressure attributed to the often hypoxic soil-dwelling lifestyle of worms. In contrast, tissues of cnidarians harbouring phototrophic endosymbionts can tolerate extremes of oxygen saturation31, thus demanding efficient means to control oxidative damage. Accordingly, additional elaboration of Nrf2 activity in fungi and basal metazoans is essential to better elucidate evolutionary processes, which is enabled by the recent availability of several cnidarian genome annotations, including that of the scleractinian coral, Acropora digitifera32.

In summary, we demonstrate that orthologues of Nrf2 first appeared in fungi around 1.5 Ga5 during the Paleoproterozoic when photosynthetic oxygen was being absorbed into the oceans culminating in prolonged low oxidative stress1. A subsequent significant divergence in Nrf2 is seen to occur during the split between fungi and the Metazoa approximately 1.0–1.2 Ga33; at a time when oceanic ventilation released free oxygen to the atmosphere, but with most of this being absorbed by methane oxidation and oxidative weathering of land surfaces until approximately 800 Ma12,18. Atmospheric oxygen levels thereafter accumulated during the Neoproterozoic giving rise to metazoan success during the Ediacaran period (635–541 Ma) leading to the Cambrian explosion (radiation) commencing at ~541 Ma34. Atmospheric O2 levels then rose in the late Paleozoic (359–252 Ma), driving further Nrf2 sequence divergence and Keap1 recruitment for Keap1-Nrf2 regulation of the oxidative stress response at the division between mammals and non-mammalian vertebrates during the during the Late Triassic (~225 Ma)35,36. Understanding the evolution of Nrf2 and recruitment of other protein partners into an effective antioxidant response cascade might provide novel insights into the human aging process since oxidative stress is believed to be one of the key factors in aging. This could, in turn, reveal possible new intervention strategies to improve metabolic health in our worldwide ageing population.

Methods

The Nrf2 phylogenetic tree was constructed using BEAST version 2.3.037 using a selection of Nrf2 homologs sourced from major metazoan and fungal phyla, and basic leucine zipper transcription factors from plant and cyanobacteria are utilised as outgroups. Sequences were aligned using T-Coffee Expresso38 and T-Coffee Psi-Coffee38 aligners and were evaluated using the T-Coffee TCS method to verify multiple alignment transitional consistencies39. The phylogenetic tree was calibrated based on best paleontological estimates for the emergence of Eukaryota, the metazoan-fungal split and a set of animal phyla divides using compiled data from previous studies6,7,33,40, In order to assess the robustness of phylogenetic reconstruction and selective pressures in the evolution of Nrf2 based on increasing oxidative stress, data were split into subgroups (Mammals, Amniotes, Tetrapods, Vertebrates, Deuterostomia, Bilateria, Eumetazoa and early Eukarya datasets) to examine protein and DNA sequence divergence using MEGA 641. For each group, sequences were aligned using ClustalW42, and alignments were analysed using the HyPhy test of codon selection and a codon-based Z test of selection for DNA sequences24. Accordingly, Maximum Likelihood and Neighbor Joining Trees were constructed for each group, and tree topologies were compared to verify consistency of results. Tests confirmed the robustness of taxonomical grouping and codon-based selection tests within and between animal subgroups (data not shown). Multiple alignments with Nrf2-like DNA plant sequences were not of sufficient quality to perform Codon-based tests of selection. Detailed bioinformatics methodology is provided in Supplementary Data File 1.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Gacesa, R. et al. Rising levels of atmospheric oxygen and evolution of Nrf2. Sci. Rep. 6, 27740; doi: 10.1038/srep27740 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Prof. Dr. Antonio C. Marques and Prof. Dame Janet M. Thornton FRS for critically reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council (MRC grant G82144A).

Footnotes

Author Contributions R.G., W.C.D. and P.F.L. conceived the study. R.G. and R.A.L. carried out the bioinformatics analysis. R.G., W.C.D. and P.F.L. interpreted the data. D.J.B., R.A.L. and P.F.L. participated in the design and co-ordination. W.C.D. and P.F.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version.

References

- Holland H. D. The oxygenation of the atmosphere and oceans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 361, 903–15 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirrmeister B. E., de Vos J. M., Antonelli A. & Bagheri H. C. Evolution of multicellularity coincided with increased diversification of cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 1791–6 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lushchak V. I. Adaptive response to oxidative stress: Bacteria, fungi, plants and animals. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 153, 175–90 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn M. B. & Liby K. T. NRF2 and cancer: the good, the bad and the importance of context. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 564–71 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gacesa R., Dunlap W. C. & Long P. F. Bioinformatics analyses provide insight into distant homology of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88, 373–380 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspermeyer J. New grand tree of life study shows a clock-like trend in the emergence of new species and diversity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 1113–1113 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges S. B., Marin J., Suleski M., Paymer M. & Kumar S. Tree of life reveals clock-like speciation and diversification. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 835–845 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berner R. A. & Canfield D. E. A new model for atmospheric oxygen over Phanerozoic time. Am. J. Sci. 289, 333–361 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berner R. A. GEOCARBSULF: A combined model for Phanerozoic atmospheric O2 and CO2. 70, 5653–5664 (2006).

- Berner R. A. Phanerozoic atmospheric oxygen: New results using the GEOCARBSULF model. Am. J. Sci. 309, 603–606 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Harada M., Tajika E. & Sekine Y. Transition to an oxygen-rich atmosphere with an extensive overshoot triggered by the Paleoproterozoic snowball Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 419, 178–186 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Lyons T. W., Reinhard C. T. & Planavsky N. J. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307–15 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling E. A., Halverson G. P., Knoll A. H., MacDonald F. A. & Johnston D. T. A basin redox transect at the dawn of animal life. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 371–372, 143–155 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D. T. et al. Late Ediacaran redox stability and metazoan evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 335–336, 25–35 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Anbar A. D. et al. A whiff of oxygen before the great oxidation event? Science 317, 1903–1906 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp R. E., Kirschvink J. L., Hilburn I. a. & Nash C. Z. The Paleoproterozoic snowball Earth: a climate disaster triggered by the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11131–11136 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen B., Fletcher I. R., Brocks J. J. & Kilburn M. R. Reassessing the first appearance of eukaryotes and cyanobacteria. Nature 455, 1101–1104 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planavsky N. J. et al. Low mid-proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635–638 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills D. B. & Canfield D. E. Oxygen and animal evolution: Did a rise of atmospheric oxygen trigger the origin of animals? BioEssays 36, 1145–1155 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. et al. Sufficient oxygen for animal respiration 1,400 million years ago. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 1731–1736 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Och L. M. & Shields-Zhou G. A. The Neoproterozoic oxygenation event: Environmental perturbations and biogeochemical cycling. Earth-Science Rev. 110, 26–57 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Shao H., Chu L., Shao M., Jaleel C. A. & Mi H. Higher plant antioxidants and redox signaling under environmental stresses. C. R. Biol. 331, 433–41 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomitani A. et al. Chlorophyll b and phycobilins in the common ancestor of cyanobacteria and chloroplasts. Nature 400, 159–162 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. & Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 3, 418–426 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe K. P., Leung C. K. & Miyamoto M. M. Unique structure and regulation of the nematode detoxification gene regulator, SKN-1: implications to understanding and controlling drug resistance. Drug Metab. Rev. 44, 209–223 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J. H. et al. Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans oxidative stress defense protein SKN-1 by glycogen synthase kinase-3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16275–80 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykiotis G. P. & Bohmann D. Keap1/Nrf2 signaling regulates oxidative stress tolerance and lifespan in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 14, 76–85 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitoniak A. & Bohmann D. Mechanisms and Functions of Nrf2 Signaling in Drosophila. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88, 302–313 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell T. K., Steinbaugh M. J., Hourihan J. M., Ewald C. Y. & Isik M. SKN-1/Nrf, stress responses, and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88, 290–301 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguinaldo A. M. et al. Evidence for a clade of nematodes, arthropods and other moulting animals. Nature 387, 489–493 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl M., Cohen Y., Dalsgaard T., Jorgensen B. B. & Revsbech N. P. Microenvironment and photosynthesis of zooxanthellae in scleractinian corals studied with microsensors for O2, pH and light. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 117, 159–177 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap W. C. et al. KEGG orthology-based annotation of the predicted proteome of Acropora digitifera: ZoophyteBase - an open access and searchable database of a coral genome. BMC Genomics 14, 509 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges S. B., Blair J. E., Venturi M. L. & Shoe J. L. A molecular timescale of eukaryote evolution and the rise of complex multicellular life. BMC Evol. Biol. 4, 1–9 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin D. H. et al. The Cambrian conundrum: early divergence and later ecological success in the early history of animals. Science 334, 1091–1097 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z. X., Yuan C. X., Meng Q. J. & Ji Q. A Jurassic eutherian mammal and divergence of marsupials and placentals. Nature 476, 442–445 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z. & Martin T. Analysis of molar structure and phylogeny of docodont genera. Bull. Carnegie Museum Nat. Hist. 39, 27–47 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Bouckaert R. et al. BEAST 2: A Software Platform for Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10, 1–6 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tommaso P. et al. T-Coffee: A web server for the multiple sequence alignment of protein and RNA sequences using structural information and homology extension. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 1–5 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.-M., Di Tommaso P. & Notredame C. TCS: A new multiple sequence alignment reliability measure to estimate alignment accuracy and improve phylogenetic tree reconstruction. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 1625–1637 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. Y., Kumar S. & Hedges S. B. Divergence time estimates for the early history of animal phyla and the origin of plants, animals and fungi. Proc. Biol. Sci. 266, 163–71 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A. & Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–9 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. A. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranendonk M. J. Van. In Geol. Time Scale 2012 2-Volume Set (Felix M. G., OggMark James G., Schmitz D. & Gab M. O.) 299–392 (Elsevier, 2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.