Abstract

Background

Histopathological B3 lesions after minimal invasive breast biopsy (VABB) are a particular challenge for the clinician, as there are currently no binding recommendations regarding the subsequent procedure.

Purpose

To analyze all B3 lesions, diagnosed at VABB and captured in the national central Swiss MIBB database and to provide a data basis for further management in this subgroup of patients.

Material and Methods

All 9,153 stereotactically, sonographically, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided vacuum-assisted breast biopsies, performed in Switzerland between 2009 and 2011, captured in a central database, were evaluated. The rate of B3 lesions and the definitive pathological findings in patients who underwent surgical resection were analyzed.

Results

The B3 rate was 17.0% (1532 of 9000 biopsies with B classification). Among the 521 lesions with a definitive postoperative diagnosis, the malignancy rate (invasive carcinoma or DCIS) was 21.5%. In patients with atypical ductal hyperplasia, papillary lesions, flat epithelial atypia, lobular neoplasia, and radial scar diagnosed by VABB, the malignancy rates were 25.9%, 3.1%, 18.3%, 26.4%, and 11.1%, respectively.

Conclusion

B3 lesions, comprising 17%, of all analyzed biopsies, were common and the proportion of malignancies in those lesions undergoing subsequent surgical excision was high (21.5%).

Keywords: Breast cancer, B3 lesion, vacuum-assisted breast biopsy, uncertain malignant potential, invasive carcinoma, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

Introduction

Minimally invasive breast biopsies (MIBB) are performed to clarify unclear mammographic, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of the breast. Vacuum-assisted breast biopsy (VABB) has proved to be among the most efficient means of obtaining tissue, guided by ultrasound, stereotactic techniques, or MRI (1). B classification has become the established standard for the classification of histopathological findings in breast biopsies (2,3). It is routinely applied in Switzerland since 2011 and underpins the quality guidelines of the Swiss Society of Pathology (SGPath) (4,5). In this regard, lesions classified as B3 (benign lesions with unclear biological potential) represent a particular challenge for clinicians making decisions about further management. B3 lesions include various entities such as atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), flat epithelial atypia (FEA), lobular neoplasia (LN), larger or multiple papillary lesions, radial scar/complex sclerosing lesion (RS), and the phylloides tumor (6) (the phylloides tumor entity has only been listed in the database since 2011 and was therefore excluded from our analysis). The interpretation of current evidence has led to guidelines for further management that range from follow-up resection to “watchful waiting” (6–13).

As a legal requirement and as stipulated by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (BAG), all breast biopsies performed at the 52 MIBB centers in Switzerland must be registered in a central database for quality control purposes.

The aim of the present study was to analyze the rate of B3 lesions and the definitive pathological findings in patients who underwent subsequent surgical resection. The results were compared with the current literature and are intended to guide the development of new recommendations regarding further management after a B3 lesion has been diagnosed by vacuum biopsy.

Material and Methods

MIBB database

As directed by the BAG and within the scope of legal requirements, all MIBBs or vacuum biopsies performed in Switzerland are recorded by the MIBB Group (Minimally-invasive Breast Biopsy Group), a working group of the Swiss Senological Society. A consensus meeting of this group was held in 2008, during which guidelines regarding the requirements of the contributing institutes and surgeons were formulated, as well as the requirements regarding the cooperation with other involved institutes (5). The company ADJUMED-Services GmbH (Zürich, Switzerland) generated a web-based system that records data and holds them centrally. A total of 52 MIBB centers in Switzerland currently participate in the database. Data input was performed by a designated responsible individual at each institute. All data recorded in the database from 2009 to 2011 were evaluated for the study, which encompassed a total of 9153 biopsies. All data were anonymized so that individual patients or institutions could not be identified.

Study population

In this study, 9153 biopsies were performed between 2009 and 2011 and entered into the MIBB database until the end of 2012. All biopsies were evaluated with the objective of determining the frequency of B3 lesions among the total number of biopsies, the precise histological diagnosis of each occurrence, and how often B3 lesions were upstaged to a malignant finding after open resection.

Patients who had undergone ultrasound-, stereotactic-, or MRI-guided vacuum biopsy were informed by a standardized explanatory form that their data would be made available to experts and public authorities in anonymized form for evaluation within the scope of quality assurance, and might be published in specialist literature in the same anonymized form (14–16). The explanatory discussion was held by the person who performed the operation at the respective institute.

The responsible ethics committee has approved the use of these data within the scope of this study.

Processing of raw data/inclusion/exclusion criteria

The database’s online questionnaire encompasses several categories, which were “benign without atypia, papillary lesion (PL), radial scar (RS), lobular neoplasia (LN), flat epithelial atypia (FEA), atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), and invasive Carcinoma.

All patients with known histopathological B3 diagnosis and definitive histology after surgical resection were included. If there was no or unclear information provided for an individual outcome, as the option “other” had been chosen by data entry personnel, these were interpreted as missing data and excluded.

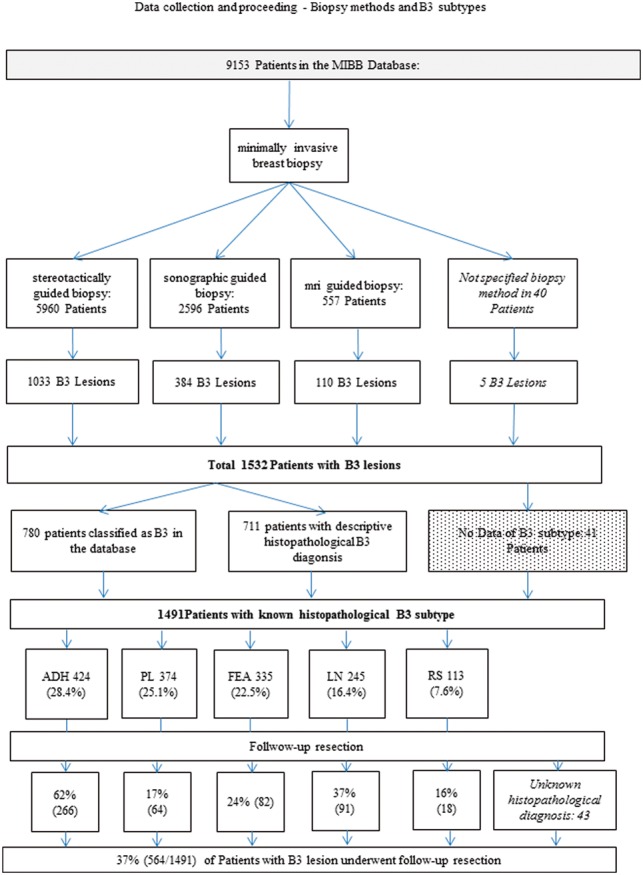

The rate of “missing” data records is listed for each evaluation. Entering information concerning B classification in the database had been optional and thus was not always entered, although it became an obligatory part of the histopathological test report in accordance with SGPath Guidelines in 2011. B classification was specifically recorded on 5305 occasions (of 9153 in total), of which 780 were classified as B3, encompassing the diagnoses of ADH, LN, papillary lesion, FEA, and RS. However, as 8883 data records were accompanied by a descriptive diagnosis, if a B classification was absent, we were able to retrospectively assign one based on the histopathological findings. Allocating a B3 classification to all diagnoses of ADH, LN, papillary lesion, FEA, and RS resulted in a total of 9000 records, of which 1532 were classified as B3 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Data collection and data management flow chart of all patients in the database and distribution of B classification.

Image-guided vacuum biopsy technique

Biopsies were performed according to established guidelines (2,5,17–19). All centers fulfilled the structural prerequisites required for the implementation of MIBBs (5). MIBB Guidelines recommend using needle thicknesses of 11 G or thicker, sampling of >12 cores in stereotactically-guided MIBB and sampling of five to 10 cores in sonographically guided MIBB. In our study population, the average needle diameter was 9 G, and the average number of core biopsy specimens taken was 14 per patient (for each biopsy method). The needles we used were: Mammatome 8 G and 11 G (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA); Suros 9 G and 11 G (Hologic, Bedford, MA, USA); Vacora 11 G and 14 G (BARD, Murray Hill, NJ, USA); Encor 7 G, 10 G, and 12 G (SenoRx, Irvine, CA, USA); Finesse 14 G (BARD). For analysis, we only distinguished between the sizes of the needles used (7 G to 14 G) and not the manufacturers. After creating the dissection diagram, we transferred the cores into buffered 4% formalin solution.

Processing of tissue samples

Histopathological processing was undertaken in accordance with the Quality Guidelines of the SGPath (4). Cores were fixed in a 4% buffered formalin solution for at least 6 h. Each core biopsy was then transferred to a tissue cassette and poured into a paraffin block. We then prepared sections in three increments with two to three serial sections each, which were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. We also prepared some unstained sections for immunohistochemical staining if necessary.

Histopathological diagnosis

The histopathological diagnoses of the breast biopsies, especially the high-risk lesions discussed in this paper, were made by experienced pathologists in accordance with World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (20). B3 lesions and initial diagnoses of malignant disease were confirmed with the “second look” method by a second pathologist.

Statistical analysis

B classifications were compared between biopsy methods using the Mann-Whitney test with exact P values. To address multiple comparisons between groups, a Bonferroni correction was performed. Consequently, P values less than 0.017 were considered statistically significant in this analysis. The proportion of malignant lesions in the definite histopathology was compared between patients with BI-RADS 3, 4, and 5 using the chi-square test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

Biopsy methods

The method of biopsy was not specified in 40 of the 9153 patients. The majority (65.4%) underwent stereotactically-guided biopsy (5960/9113), 28.5% underwent sonographically-guided biopsy (2596/9113), and 6.1% (557/9113) underwent MRI-guided biopsy. Specification of the biopsy method was not available in five of the patients with a B3 lesion (n = 1532). Of the patients with a B3 lesion, 67.6% (1033/1527) underwent stereotactically-guided biopsy, 25.1% (384/1527) underwent sonographically-guided biopsy and 7.2% (110/1527) underwent MRI-guided biopsy (Fig. 1).

Distribution of B lesions

In 1.7% (153/9,153) of the biopsies, no statements regarding B classification or no allocation to a B classification could be made. The remaining 9000 biopsies resulted in the following B classifications: B1, 1.4% (n = 125); B2, 60.8% (n = 5473); B3, 17.0% (n = 1532); B4, 0.0004% (n = 4); and B5, 20.7% (n = 1866) of lesions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of B classification after VABB, diagnosis, and presence of micro-calcification in B3 lesions and definitive histopathological diagnosis after open resection in patients with B3 lesions.

| B classification after VABB | n (%) | Histopathological diagnosis | Number (proportion of B3 lesions, %) | Number with micro-calcification (proportion of diagnosis, %) | Definitive histopathological diagnosis after open resection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 125 (1.4%) | ||||

| B2 | 5473 (60.8%) | ||||

| B3 | 1532 (17.0%) | ADH | 424 (28.4%) | 346 (81.6%) | 108 (20.7%) |

| PL | 374 (25.1%) | 135 (36.1%) | 47 (9%) | ||

| FEA | 335 (22.5%) | 294 (87.8%) | 46 (8.8%) | ||

| LN | 245 (16.4%) | 178 (72.7%) | 64 (12.3%) | ||

| RS | 113 (7.6%) | 72 (63.7%) | 13 (2.5%) | ||

| Invasive carcinomas | 45 (8.6%) | ||||

| DCIS | 67 (12.9%) | ||||

| Benign lesion | 131 (25.1%) | ||||

| Total | 1491 (100%) | 1025 (69%) | 521 (21.5%) | ||

| Missing | 41 (2.7%) | 21 (n/a) | |||

| B4 | 4 (<0.01%) | ||||

| B5 | 1866 (20.7%) | ||||

| Total | 9000 | ||||

| Not specified | 153 (1.7%) | ||||

| Total | 9153 (100.0%) | 1532 (100.0%) | 1046 | ||

Frequency of B3 subtypes

For a small proportion of B3 lesions (2.7%, 41/1532) no histopathology result was recorded The B3 lesions comprised the following histopathological diagnoses: ADH, 28.4% (424/1491); PL, 25.1% (374/1491); FEA, 22.5% (335/1491); LN, 16.4% (245/1491); and RS, 7.6% (113/1491) (Table 1).

Association of B3 lesions with micro-calcification

At 87.8% (294/335), FEA was most frequently associated with micro-calcification, followed by ADH at 81.6% (364/424), LN at 72.7% (178/245), radial scar at 63.7% (72/113), and papillary lesion at 36.1% (135/374) (Table 1).

Completeness of imaging-assisted removal of B3 lesions, as assessed on mammography, and clip inserts

A total of 65.0% of PL (90/260) were successfully removed by imaging-based techniques, followed by RS at 48.1% (39/77), LN at 45.5% (81/178), ADH at 44.4% (123/277), and FEA at 35.1% (79/225) (P < 0.001). Clips were inserted 75% of VABB on average between 2009 and 2011.

Definitive histopathological findings in follow-up resection material

A total of 37.8% (564/1491) of patients with a B3 diagnosis were subjected to follow-up resection after minimally invasive biopsy (Fig. 1). Of these, no further histopathological diagnosis was listed in the database for 43 patients (specified as: Other). Therefore, 34.9% (521/1491) of the cases provided information on definitive histopathology after open resection of a B3 lesion (Table 2). The proportion of malignancies in the definitive histopathology for all B3 lesions was therefore 21.5% (112/521). Of the B3 diagnoses made on VABB, ADH was most frequently subject to follow-up resection with 62% (266/424) (Fig. 1). ADH and LN were most often found to have a malignant diagnosis on definitive histology with 25.9% and 26.4% (Table 1).

Table 2.

Proportion of malignant lesions of each B3 subdiagnosis and comparison with the literature.

| ADH |

FEA |

LN |

RS |

PL |

Proportion of B3 |

Overall PML for B3 lesions |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PML | n/N* | PML | n/N | PML | n/N | PML | n/N | PML | n/N | % | n | PML | n/N | |

| This study (2012) | 0.26 | 69/266 | 0.18 | 15/82 | 0.26 | 24/91 | 0.11 | 2/18 | 0.03 | 2/64 | 17.0% | 1532/9153 | 0.21 | 112/521 |

| Bianchi, 2011 (7) | 0.27 | 197/721 | 0.12 | 31/245 | 0.22 | 83/377 | 0.10 | 14/132 | 0.13 | 18/135 | 11.9% | 3107/26,165 | 0.21 | 349/1644 |

| Dillon, 2007 (8) | 0.35 | 14/40 | 0.40 | 4/9 | 0.17 | 9/54 | 0.18 | 5/28 | 5.7% | 211/3729 | 0.21 | 37/177 | ||

| El-Sayed, 2008 (9) | 0.32 | 61/188 | 0.30 | 8/27 | 0.12 | 19/156 | 0.11 | 13/124 | 5.2% | 705/13,452 | 0.2 | 106/523 | ||

| Hayes, 2009 (10) | 0.32 | 8/25 | 0.13 | 1/8 | 0.50 | 3/3 | 0.12 | 7/57 | 0.08 | 2/24 | 7.7% | 141/1829 | 0.16 | 22/141 |

| Houssami, 2007 (6) | 0.45 | 63/141 | 0.61 | 14/23 | 0.17 | 7/42 | 0.23 | 10/44 | 9.2% | 372/4035 | 0.3 | 98/279 | ||

| Lee, 2003 (11) | 0.46 | 13/28 | 0.66 | 6/9 | 0.20 | 5/25 | 0.15 | 3/20 | 3.0% | 116/3822 | 0.3 | 29/96 | ||

| Lieske, 2008 (12) | 0.50 | 36/72 | 1.00 | 1/1 | 0.38 | 9/24 | 0.09 | 4/43 | 0.26 | 9/35 | 5.4% | 220/4080 | 0.34 | 67/199 |

| Noske, 2010 (13) | 0.36 | 5/14 | 0.07 | 5/14 | 0.00 | 0/6 | 0.00 | 0/7 | 0.07 | 1/15 | 6.6% | 122/1854 | 0.1 | 881 |

n/N = count of malignant lesions after open resection (n) from the total of B3 lesions in the histopathological subdiagnosis (N).

ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia; FEA, flat epithelial atypia; LN, lobular neoplasia; PL, papillary lesion; PML, proportion of malignant lesions; RS, radial scar; VABB, vacuum-assisted breast biopsy.

Discussion

We studied a large population, closely representative of Switzerland, using an expertly curated database that recorded the details of all registered vacuum-assisted breast biopsies performed in the 52 MIBB centers. This allowed us to analyze a large number of B3 lesions (n = 1491, 41 “missing” data records). In our cohort, only 37.8% obtained follow-up resection, which is a relatively small proportion when compared with other studies (9,21). Therefore, fewer definitive histopathological diagnoses were available. Nevertheless, the proportion of our cohort diagnosed with B3 lesions was relatively high (17.0%) compared with other studies (3,21). The proportion of B3 lesions later found to be malignant in our study was 21.5%.

Atypical ductal hyperplasia was the most common diagnosis within the B3 classification after VABB, comprising 28.4% of diagnoses, which concurs with the findings of other investigators (22). However, on definitive histology from resection specimens, 25.9% of lesions originally diagnosed as ADH proved to be malignant. Other investigators have reported that ADH is the lesion with the greatest potential for malignancy (7,10). Atypical ductal hyperplasia is defined as the presence of homogenous involvement of at least two membrane-bound spaces or comprising a size of >2 mm (WHO Classification of Tumors of the Breast, 4th Edition). A sampling error may also lead to the diagnosis of ADH rather than a low-grade DCIS, which is dependent on the diameter of needle used (7). Like many other investigators (6,7,9,10), we recommend that patients diagnosed with ADH should always be subjected to definitive surgical follow-up resection.

In our cohort, the papillary lesion was the second most frequently diagnosed lesion after VABB, comprising 25.1% of B3 lesions, a slightly lower proportion than reported by other studies (7,9,10,22). The proportion of these lesions that later proved to be malignant was 3.1%, which is lower than the range of 7–26% found in most other cohorts except that of Sydnor et al. (Table 2) (23).

Some investigators have recommended stereotactically-guided vacuum biopsy as an alternative to complete resection for papillary lesions (24,25), reserving complete surgical excision for lesions with atypia (9). Patients not undergoing surgery should be subjected to follow-up mammographic and ultrasound screening at regular intervals.

Flat epithelial atypia was the third most frequent diagnosis (22.5%) within B3 lesions, which is broadly similar to other studies (6–13), although at 18.3% the proportion of malignancies was relatively high (7,10,12,13).

Flat epithelial atypia is generally considered to be the first objectifiable change or pre-stage of a low-grade carcinoma (26) although DCIS, LN and invasive carcinoma are also associated with FEA (7,26). Our study shows that 18.3% of lesions classified as FEA on VABB later proved to be malignant after surgical resection, which is broadly similar to the findings of Bianki et al. (12%) (7). Follow-up resection in the event of a diagnosis of FEA is a sensible approach when residual calcification is still present after the biopsy, as FEA is associated with micro-calcification in 99% of cases in the literature (27) and 87.8% in this study.

In our cohort, LN comprised 16.4% of B3 lesions and 26.4% later proved to be malignant after excision; these are both relatively low proportions compared with the literature (Table 2) with the exception of Bianchi et al. findings (7). While several investigators have proposed routine excision (28), others support surveillance follow-up without open resection (29).

Radial scar was the most infrequent B3 lesion in our study, comprising 7.6% of the total. Noske et al. reported a lower incidence of 5% (13) but other studies have found an incidence of 15–40% (7). Although only 11.1% of the radial scars identified by VABB in our study were associated with malignancies in follow-up resection material, this is still a higher frequency than those reported by other investigators (6,8,11). Generally, it is considered that surgical resection should be offered for radial scars, as the malignant potential has been reported to be as high as 30%. Based on imaging, complete removal with radial scars was documented in our cohort with 48%. Unfortunately, radial scars are prone to get masked by minor bleeding and scarring and the upgrade rate to malignancy is high, as reported by other investigators, even in small radial scars (30). Thus, imaging findings might be misleading and radio-pathologic-correlation has to be done with caution. According to our findings, such a procedure should be specifically discussed when the lesion was not completely removed by morphological imaging means (for example in the case of residual calcification), and the finding was marked using a clip. Image-based follow-up control should follow approximately 6 months after a biopsy to check whether complete removal of the lesion had been achieved.

Our study had several limitations. The size of our database allowed us to analyze vast amounts of data, and the responsible person in each of the 52 centers entered the data. If input errors were made, they were not traceable as data had been anonymized. Furthermore, some data were missing or incomplete: on 2.9% (270/9,153) of occasions, the histopathological diagnosis of the breast biopsy had not been recorded. Furthermore, B classification was only specified in 58.0% (5305/9153) of cases, of which 14.7% (n = 780) were classified as B3. Specification of B classification was not common or obligatory for a period during the study; therefore, when these data were missing we retrospectively assigned a B classification based on the histopathological diagnosis. Furthermore, there is no consequent correlation with imaging findings, i.e. mammography. In addition, the database did not provide information about the histological subtype and the size of cancers. In our cohort, only 18 of 118 radial scars underwent open resection, which is a rather low rate. The database did record whether patients diagnosed with a B3 lesion by VABB who were not offered surgical resection were instead offered imaging surveillance, but not the result of it. Furthermore, the reasoning behind decisions to adopt a strategy of “watchful waiting” was not recorded. A selection bias may also have been introduced as a consequence of the smaller proportion of patients with B3 lesions (37.8%) requiring follow-up resection compared with other published studies. This potential bias should be taken into account when interpreting the relatively high rate of malignant findings after follow-up excision. The fact that surgery was not routinely performed is likely to result in an overestimation of the frequency of upstaging to malignancy on excisional biopsy compared to a cohort of women in which excision would be routinely performed for high-risk lesions.

In conclusion, B3 lesions (17% of all analyzed biopsies) were more common in our database than expected from the literature. The overall rate of malignant findings detected at follow-up excision was 21.5%, being highest for ADH and LN. Because of the high rate of malignant findings, surgical management needs to be interdisciplinary discussed in B3 lesions at VABB. Watchful waiting can be justified in selected cases with adequate patient information depending on the patient’s preference and imaging constellations.

Acknowledgements

Another study entitled “MRI-guided vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: Comparison with stereotactically- and sonographically-guided techniques” [50] was performed using the same database by Thomas Imschweiler, Harald Haueisen, Gert Kampmann, Luzi Rageth, Burkhardt Seifert, Christoph Rageth, Bianka Chilla, and Rahel A Kubik-Huch.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, support, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Park HL, Kim LS. The current role of vacuum assisted breast biopsy system in breast disease. J Breast Cancer 2011; 14: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis IO, Michell M, Pinder SE, et al. Guidelines for non-operative diagnostic procedures and reporting in breast cancer screening, London: NHSBSP, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreu FJ, Sáez A, Sentís M, et al. Breast core biopsy reporting categories–An internal validation in a series of 3054 consecutive lesions. Breast 2007; 16: 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zenklusen, Dirnhofer, Bubendorf, et al. Qualitätsrichtlinien der schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Pathologie SGPath [in German]. 2011. Available at: http://www.sgpath.ch/docs/QR_SGPath_DE_2011.pdf.

- 5.Köchli O R, Rageth J C, Brun del Re R, et al. Bildgesteuerte minimalinvasive Mammaeingriffe: Konsensusstatements für die Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Senologie (SGS) und die Arbeitsgruppe Bildgesteuerte minimalinvasive Mammaeingriffe [in German]. Senologie - Zeitschrift für Mammadiagnostik und therapie 2009;6:181–184. Available at: http://www.mibb.ch/Documents/Seno_3-09_S181-184_Rageth.aspx.

- 6.Houssami N, Ciatto S, Bilous M, et al. Borderline breast core needle histology: predictive values for malignancy in lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3). Br J Cancer 2007; 96: 1253–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianchi S, Caini S, Cattani MG, et al. Diagnostic concordance in reporting breast needle core biopsies using the B classification-A panel in Italy. Pathol Oncol Res 2009; 15: 725–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dillon MF, McDermott EW, Hill AD, et al. Predictive value of breast lesions of “uncertain malignant potential” and “suspicious for malignancy” determined by needle core biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; 14: 704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Sayed ME, Rakha EA, Reed J, et al. Predictive value of needle core biopsy diagnoses of lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) in abnormalities detected by mammographic screening. Histopathology 2008; 53: 650–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes BD, O’Doherty A, Quinn CM. Correlation of needle core biopsy with excision histology in screen-detected B3 lesions: the Merrion Breast Screening Unit experience. J Clin Pathol 2009; 62: 1136–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee AH, Denley HE, Pinder SE, et al. Excision biopsy findings of patients with breast needle core biopsies reported as suspicious of malignancy (B4) or lesion of uncertain malignant potential (B3). Histopathology 2003; 42: 331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieske B, Ravichandran D, Alvi A, et al. Screen-detected breast lesions with an indeterminate (B3) core needle biopsy should be excised. Eur J Surg Oncol 2008; 34: 1293–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noske A, Pahl S, Fallenberg E, et al. Flat epithelial atypia is a common subtype of B3 breast lesions and is associated with noninvasive cancer but not with invasive cancer in final excision histology. Hum Pathol 2010; 41: 522–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aufklärungsprotokoll zur MRI-gesteuerten minimalinvasiven Brustbiopsie (Vakuumbiopsie) [in German]. Nunningen: Schweizeriche Gesellschaft für Senologie, 2008. Available at: http://www.mibb.ch/Documents/consensus_mri_deu-(1).aspx.

- 15.Aufklärungsprotokoll zur stereotaktischen minimalinvasiven Brustbiopsie (Vakuumbiopsie) [in German]. Nunningern: Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Senologie, 2011. Available at: http://www.mibb.ch/Documents/consensus_ster_deu-(1).aspx.

- 16.Aufklärungsprotokoll zur untraschallgesteuerten minimalinvasiven Brustbiopsie (Vakuumbiopsie) [in German]. Nunningen: Schweizeriche Gesellschaft für Senologie, 2011. Available at: http://www.mibb.ch/Documents/consensus_us_deu-(1).aspx.

- 17.Albert U-S. Stufe-3-Leitlinie Brustkrebs-Früherkennung in Deutschland [in German]. W. Wien: Zuckschwerdt Verlag München, 2008. Avaiable at: http://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/077-001_S3_Brustkrebs-Frueherkennung_lang_02-2008_02-2011.pdf.

- 18.Wallis M, Tardivon A, Helbich T, et al. Guidelines from the European Society of Breast Imaging for diagnostic interventional breast procedures. Eur Radiol 2007; 17: 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. Fourth edition–summary document. Ann Oncol 2008; 19: 614–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tavassoli F A, Devilee P. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors: Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Geneva: WHO, 2003. Available at: http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/pat-gen/bb4/BB4.pdf.

- 21.Pagni F, Bosisio FM, Salvioni D, et al. Application of the British National Health Service Breast Cancer Screening Programme classification in 226 breast core needle biopsies: correlation with resected specimens. Ann Diagn Pathol 2012; 16: 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weigel S, Decker T, Korsching E, et al. Minimal invasive biopsy results of “uncertain malignant potential” in digital mammography screening: high prevalence but also high predictive value for malignancy. Rofo 2011; 183: 743–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sydnor MK, Wilson JD, Hijaz TA, et al. Underestimation of the presence of breast carcinoma in papillary lesions initially diagnosed at core-needle biopsy. Radiology 2007; 242: 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carder PJ, Khan T, Burrows P, et al. Large volume “mammotome” biopsy may reduce the need for diagnostic surgery in papillary lesions of the breast. J Clin Pathol 2008; 61: 928–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tennant SL, Evans A, Hamilton LJ, et al. Vacuum-assisted excision of breast lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) - an alternative to surgery in selected cases. Breast 2008; 17: 546–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinder SE, Reis-Filho JS. Non-operative breast pathology: columnar cell lesions. J Clin Pathol 2007; 60: 1307–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chivukula M, Bhargava R, Tseng G, et al. Clinicopathologic implications of “flat epithelial atypia” in core needle biopsy specimens of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol 2009; 131: 802–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Destounis SV, Murphy PF, Seifert PJ, et al. Management of patients diagnosed with lobular carcinoma in situ at needle core biopsy at a community-based outpatient facility. Am J Roentgenol 2012; 198: 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang H, Barke LD, Mendelson EB, et al. Atypical lobular hyperplasia and classic lobular carcinoma in situ in core biopsy specimens: routine excision is not necessary. Mod Pathol 2008; 21: 1208–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mokbel K, Price RK, Mostafa A, et al. Radial scar and carcinoma of the breast: microscopic findings in 32 cases. Breast 1999; 8: 339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]