Abstract

Increased body mass index (BMI) at diagnosis has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of disease recurrence and death. However, the association has not been consistent in the literature and may depend on several factors such as menopausal status, extent of disease, and receptor status. We performed a secondary analysis on what we believe is the largest prospective trial of adjuvant chemotherapy to assess the effect of BMI on prognosis in women with lymph node positive breast cancer. The study included 636 women with a median follow-up of over 13 years. Cox’s proportional hazards regression model was used to assess the effect of BMI on outcomes. Kaplan–Meier methods were used to estimate survival curves and log rank tests were used to assess differences in survival for BMI groups. We found that increased BMI was generally predictive of faster time to recurrence and decreased survival, but that the relationship was stronger for younger women, those with progesterone receptor negative disease and those with a greater number of lymph nodes that were positive.

Keywords: BMI, breast cancer, recurrence, time to recurrence, weight

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death among women in the United States. One in eight women will develop breast cancer in her lifetime. In 2007, an estimated 178480 women will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer and 40,460 will die from this disease (1). Approximately, 30% of newly diagnosed patients will present with stage II disease, and despite advances in adjuvant treatment, many of these women will eventually relapse and die of cancer. It is important to recognize those patients who may benefit from new therapies and identify modifiable aspects of life style that may improve prognosis. One potentially modifiable risk factor that has received much attention in recent years is body size quantitated by weight, body mass index (BMI), waist / hip ratio, and various other measures.

The relationship between body size and breast cancer risk and prognosis has been attributed to the fact that high levels of body fat are associated with high levels of serum estrogen. The hormonal profile apparent with obesity, including alterations in estradiol and insulin-like growth factor, and their binding proteins, is thought to promote growth of breast tumors (2,3). Both the conversion of androgens by the aromatase enzyme in fat tissue (4,5) and a decrease in sex hormone binding globulin shown to lower estrogen activity (5–7) have been reported to impact serum estrogen levels. The resulting higher levels of estrogen may alter growth and aggressiveness of a breast tumor. Accordingly, estrogen receptor (ER) status and menopausal status would appear to be important characteristics of an obesity-driven breast tumor.

Epidemiologic data also supports this hypothesis. Goodwin and Boyd (8) reviewed 13 cohort studies and 1 case–control study and noted that the majority found an association between body size and recurrence or survival. However, they noted that the relationship did not appear to be consistent across all women and appeared to be stronger in postmenopausal women and in those with uninvolved lymph nodes. Ryu et al. (9) performed a meta-analysis on 12 articles assessing the association between BMI and survival and estimated the hazard ratio (HR) for BMI (high versus low) to be 1.56. In a more recent review, Chelbowski (10) noted that 26 of 34 studies which assessed the association between weight and prognosis found a significant relationship. While the majority of these studies found that increased weight or BMI resulted in an increased risk of recurrence or death, the associations were not consistent across all patients, with results differing by extent of disease, menopausal status, and receptor status.

In summary, there is substantial evidence supporting a relationship between body size and prognosis, although it appears that the relationship is complicated and may well depend on factors such as extent of disease, age, menopausal status, and receptor status. To further explore the effect of BMI and its interactions with other covariates on breast cancer recurrence and survival, we performed a secondary analysis of data from a prospective, phase II study adjuvant trial which included 636 women with lymph node positive breast cancer. This unique dataset with long-term follow-up provides an excellent opportunity to explore the influence of BMI and how it impacted recurrence and survival.

METHODS

Patients

The methods of the phase II trial were described in detail previously (11). Briefly, treatment naïve women with stage II-III, lymph node positive breast cancer and adequate organ function were eligible. All women received either a modified radical or standard radical mastectomy, including axillary node dissection. No patient had other malignant disease, bilateral breast cancer, or a second primary breast cancer. All patients signed a protocol-specific, IRB-approved consent form prior to treatment.

Treatment consisted of a total of 30 weeks of treatment; a 6-week induction period and a 22-week maintenance period. During the 6-week induction period, women received weekly courses of intravenous (IV) cyclophosphamide (C; 400 mg / m2), adriamycin (A; 10 mg / m2), vincristine (V; 1 mg / m2); fluorouracil (F; 400 mg / m2), and daily Prednisone (40 mg / m2 orally for 21 days and then tapered off over 6 days). This was followed by a maintenance period (weeks 8 through 30), during which time women received biweekly courses of IV: C (400 mg / m2), A (20 mg / m2), V (1 mg / m2), and F (400 mg / m2). Patients with ER-positive tumors also received 10 mg Tamoxifen p.o. bid for 6 months during the maintenance phase.

Height and weight were measured at the time of enrollment and were used to calculate body surface area (BSA) for determining the chemotherapy doses. For this secondary analysis, we use baseline BMI to quantitate body size. BMI is calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared based on the baseline weight and height measurements. Information was prospectively collected for demographics, tumor characteristics, relapse, and survival. The original study protocol did not include evaluation of body weight as a risk for recurrence and survival and therefore weight was not collected prospectively.

Statistics

Cox’s proportional hazards regression model (12) was used to assess the unadjusted and adjusted effect of BMI on these outcomes. BMI was used as a continuous variable in the models. For some of the presentations, we categorized BMI as underweight to normal (<25 kg / m2), overweight (≥25 but <30 kg / m2), and obese (≥30 kg / m2), according to NHLBI guidelines (13). Kaplan–Meier (14) methods were used to estimate survival curves and logrank tests were used to assess differences in survival for the various BMI groups.

The Cox proportional hazards model can be written as follows:

where h0(t) denotes the baseline hazard at time t, and h(t, X) denotes the hazard at time t for a patient with covariates X1, X2, X3, … Covariates considered in this model, in addition to BMI, included age (continuous), menopausal status (pre versus post), race (Caucasian versus African American), number of lymph nodes removed and examined (continuous), number of involved lymph nodes (continuous), ER status (positive versus negative), and progesterone receptor (PR) status (positive versus negative). Values of 10 fmol / mg or greater for ER and PR were considered positive. Separate models were considered to assess the univariate and joint effects of these covariates. Martingale residual plots, as discussed in Therneau 1990 (15) and Therneau and Grambsch (16), were used to assess the functional form of the continuous covariates such as age and BMI. All two-way interactions between BMI and other patient characteristics were included in the model to determine if the effect of BMI differed depending on the levels of other variables. A backward stepwise algorithm was used to remove interactions that were not statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Summary

Six hundred fifty-four women were accrued to this study during a 5-year period between 1980 and 1985, and 636 of these were eligible. Follow-up continued through 1999, at which time the median follow-up was 13.7 years, and all but six surviving patients had at least 10 years of follow-up. Details of the eligibility, treatment, and a summary of the results can be found in Kimmick 2002 (11). Almost half of the women in this study were overweight or obese according to NHLBI guidelines (13). BMI ranged from 16.1 to 58.3 with a median of 24.8; 180 (28%) were overweight and 125 (20%) were obese. Characteristics for the eligible women are shown in Table 1 by BMI categories. Forty-one percent of the women were pre-menopausal; ages for these women ranged from 25 to 53 with a median of 43. Fifty-nine percent of the women were postmenopausal (48 surgically); ages for these women ranged from 42 to 73 with a median of 58. Overall, the median age was 52 years. Women who were overweight and obese were significantly older and more likely to be postmenopausal than those women with normal weights. The majority of the women were Caucasian (90%). A significantly greater percentage of African-American women were in the overweight and obese groups. Sixty-two percent of the women had ER+ tumors and 49% had PR+ tumors. These percentages did not differ significantly by BMI category. Seventy patients (11%) were missing PR data. The number of lymph nodes examined ranged from 1 to 54 with a median of 16. The number of lymph nodes found to be positive for cancer ranged from 1 to 39 with a median of 3; 52% of the women had between 1 and 3 positive lymph nodes, 32% had between 4 and 9 involved lymph nodes, and 16% had 10 or more involved lymph nodes. The latter characteristics did not differ significantly among the various BMI groups.

Table 1.

Summary of Patient Characteristics by BMI category†

| Characteristic | Normal (%) | Overweight (%) | Obese (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 330 | 180 | 125 | 636 |

| Median age in years (range)* | 50 (25–71) | 54 (27–72) | 53 (25–73) | 52 (25–73) |

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Premenopausal | 154 (47) | 61 (34) | 45 (36) | 261 (41) |

| Postmenopausal | 176 (53) | 119 (66) | 80 (64) | 375 (59) |

| Race | ||||

| African-American | 13 (4) | 28 (16) | 22 (18) | 63 (10) |

| Caucasian | 317 (96) | 152 (84) | 103 (82) | 573 (90) |

| Estrogen receptor status | ||||

| Negative | 128 (39) | 67 (37) | 49 (39) | 244 (38) |

| Positive | 202 (61) | 113 (63) | 76 (61) | 392 (62) |

| Progesterone receptor status | ||||

| Negative | 158 (54) | 81 (52) | 51 (44) | 290 (51) |

| Positive | 134 (46) | 75 (48) | 66 (56) | 276 (49) |

| Median lymph nodes examined (range)* | 15 (3–45) | 15 (1–44) | 17 (5–54) | 16 (1–54) |

| Number of lymph nodes positive | ||||

| 1–3 | 184 (56) | 92 (51) | 53 (43) | 329 (52) |

| 4–9 | 103 (31) | 57 (32) | 42 (34) | 203 (32) |

| 10+ | 43 (13) | 31 (17) | 28 (23) | 102 (16) |

BMI, body mass index.

Normal: BMI <25; Overweight: 25 ≤ BMI < 30; Obese: BMI ≥30.

Statistically significant difference among BMI groups, p-value <0.01.

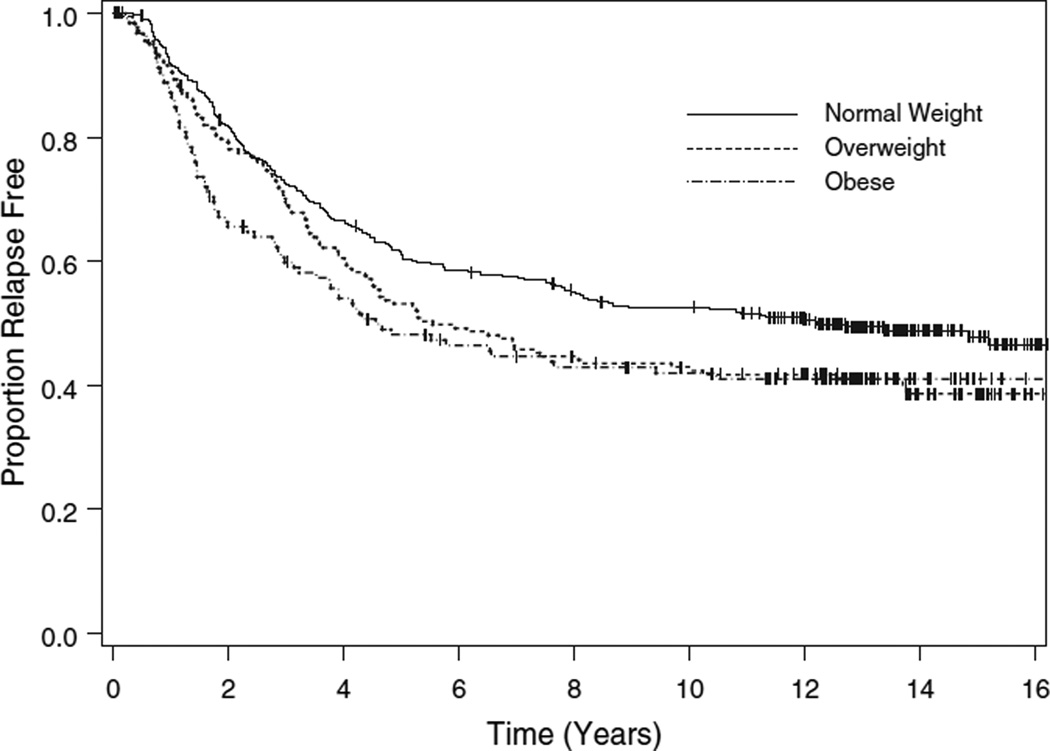

Disease-Free Survival

Two hundred sixty-one women (41%) remained alive without evidence of disease, 30 (5%) died of other causes prior to disease recurrence, and 345 (54%) recurred. Of the 345 women with recurrent disease, 34 remain alive, 8 died of other causes, and 303 died of progressive cancer. Two hundred seventythree (79%) of the recurrences occurred within 5 years of initial treatment and 53 (15%) occurred between 5 and 10 years following treatment. Overall, the median time to relapse was 7.8 years: 12.2 years in the normal weight group, 5.5 years in the overweight group, and 4.6 years in the obese group (p = 0.0417, logrank test, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Disease-free survival by body mass index category.

The results of the univariate analyses are summarized in Table 2. BMI, considered continuously, was significantly associated with recurrence (p = 0.0032). The estimated HR for BMI was 1.03 (95% CI 1.01– 1.05), indicating an approximate 3% increase in the risk of relapse for every unit increase in BMI. The number of involved lymph nodes was the most significant univariate predictor of recurrence (p < 0.0001). A log base 10 transformation was used and the risk of relapse tripled for every 10-fold increase in the number of involved lymph nodes. PR status was of borderline significance (p = 0.0148); women with PR tumors relapsed earlier than those diagnosed with PR+ tumors. The other factors considered were not univariately associated with disease-free survival.

Table 2.

Univariate Association Between Patient Characteristics and Time to Relapse

| Characteristic | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per decade) | 1.00 | 0.90–1.12 | 0.9384 |

| Menopausal status (pre versus post) | 0.90 | 0.72–1.11 | 0.3209 |

| Race (W versus AA) | 0.89 | 0.63–1.26 | 0.5168 |

| ER (+ versus −) | 0.89 | 0.72–1.11 | 0.3014 |

| PR (+ versus −) | 0.76 | 0.60–0.95 | 0.0148 |

| Log10 (lymph nodes examined) | 1.00 | 0.61–1.63 | 0.9864 |

| Log10 (number of lymph nodes positive) |

3.05 | 2.34–3.99 | 0.0001 |

| BMI (per kg / m2) | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 0.0032 |

BMI, body mass index; PR, progesterone receptor; ER, estrogen receptor.

Results of the multivariable analysis are summarized in Table 3. The two-way interactions of BMI with age, number of involved lymph nodes, and PR were statistically significant (p = 0.0145, 0.0002, and 0.0096, respectively). The other two-way interactions involving BMI were not significant. In general, a higher baseline BMI was associated with an increased risk of recurrence. However, the effect of BMI was more pronounced in younger women, those diagnosed with PR tumors, and those with more involved lymph nodes. For example, the HR for BMI was 1.16 (95% CI: 1.09–1.23) for 35-year-old women with a PR tumor and 10 involved nodes, while it was only 0.89 (95% CI: 0.84–0.95) for 65-year-old women with a PR-positive tumor and 1 involved lymph node.

Table 3.

Proportional Hazards Regression Multi-variable Model for Time to Relapse

| Characteristics | Hazard ratio |

95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Age (per decade) | ||

| BMI = 20 | 0.98 | 0.77–1.24 |

| BMI = 25 | 0.85 | 0.70–1.02 |

| BMI = 30 | 0.73 | 0.60–0.90 |

| Menopausal status (pre versus post) | 0.70 | 0.48–1.04 |

| Race (W versus AA) | 0.87 | 0.59–1.27 |

| Estrogen receptor (ER) status (+ versus −) | 0.93 | 0.72–1.21 |

| Progesterone receptor (PR) status (+ versus −) | ||

| BMI = 20 | 1.14 | 0.79–1.65 |

| BMI = 25 | 0.85 | 0.66–1.09 |

| BMI = 30 | 0.63 | 0.46–0.86 |

| Log10 (lymph nodes examined) | 0.43 | 0.24–0.76 |

| Log10 (number of lymph nodes positive) | ||

| BMI = 20 | 1.98 | 1.26–3.12 |

| BMI = 25 | 3.47 | 2.52–4.76 |

| BMI = 30 | 6.07 | 4.06–9.08 |

| BMI | ||

| PR-, 1 lymph node positive | ||

| Age = 35 | 1.04 | 0.98–1.10 |

| Age = 50 | 0.99 | 0.94–1.04 |

| Age = 65 | 0.95 | 0.89–1.01 |

| PR-, 10, number of lymph nodes positive | ||

| Age = 35 | 1.16 | 1.09–1.23 |

| Age = 50 | 1.11 | 1.07–1.15 |

| Age = 65 | 1.06 | 1.01–1.11 |

| PR+, 1 lymph node positive | ||

| Age = 35 | 0.98 | 0.92–1.04 |

| Age = 50 | 0.93 | 0.89–0.98 |

| Age = 65 | 0.89 | 0.84–0.95 |

| PR+, 10 number of lymph nodes positive | ||

| Age = 35 | 1.09 | 1.03–1.16 |

| Age = 50 | 1.04 | 1.00–1.09 |

| Age = 65 | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 |

BMI, body mass index; PR, progesterone receptor; ER, estrogen receptor.

As expected, the risk of recurrence increased as the number of involved lymph nodes increased; however, the risk was more pronounced for heavier women. For example, for women with a BMI of 20, the risk of recurrence was twice as great for women with ten involved lymph nodes compared with those with only one involved lymph node (95% CI: 1.26–3.12). For women with a BMI of 30, the HR was 6.1 (95% CI: 4.06–9.08). The effects of PR and age varied according to BMI. For obese women (BMI = 30), those who are PR+ had the least risk of relapse (HR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.46–0.86). This protective effect decreased as BMI decreases, and for women whose BMI = 20, those who were PR+ had a slightly increased risk of recurrence. Increasing age was protective, particularly for heavier women. For women with a BMI of 30, the HR per decade of life was 0.73 (95% CI: 0.60–0.90). For women with a BMI of 20, the HR per decade of life was only 0.98 (95% CI: 0.77–1.24). The number of nodes examined was also significantly associated with the risk of relapse (p = 0.0035), with those having more nodes examined being at lower risk.

Five- and ten-year disease-free survival estimates are shown in Table 4 by BMI category for subgroups of patients based on selected patient characteristics. The differences among the BMI groups were more pronounced for women with PR tumors, younger women, and women with more involved lymph nodes, in agreement with the results of the multivariable analysis.

Table 4.

Disease-Free Survival by BMI category* for Selected Subgroups of Women

| Normal |

Overweight |

Obese |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Events / n | 5 years | 10 years | Events / n | 5 years | 10 years | Events / n | 5 years | 10 years | p-value |

| Total | 167 / 330 | 0.61 (0.03) | 0.53 (0.03) | 106 / 180 | 0.53 (0.04) | 0.43 (0.04) | 72 / 125 | 0.48 (0.05) | 0.42 (0.04) | 0.0417 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤41 | 40 / 75 | 0.60 (0.06) | 0.51 (0.06) | 13 / 22 | 0.59 (0.11) | 0.41 (0.11) | 12 / 15 | 0.27 (0.11) | 0.27 (0.11) | 0.0342 |

| 42–53† | 34 / 79 | 0.69 (0.05) | 0.60 (0.06) | 27 / 39 | 0.49 (0.08) | 0.38 (0.08) | 14 / 30 | 0.63 (0.09) | 0.53 (0.09) | 0.0201 |

| 42–53‡ | 20 / 41 | 0.56 (0.08) | 0.54 (0.08) | 17 / 23 | 0.48 (0.10) | 0.26 (0.09) | 14 / 21 | 0.32 (0.10) | 0.32 (0.10) | 0.0986 |

| ≥54 | 73 / 135 | 0.59 (0.04) | 0.49 (0.04) | 49 / 96 | 0.55 (0.05) | 0.49 (0.05) | 32 / 59 | 0.52 (0.07) | 0.44 (0.07) | 0.8274 |

| Menopause | ||||||||||

| Pre | 74 / 154 | 0.65 (0.04) | 0.56 (0.04) | 40 / 61 | 0.52 (0.06) | 0.39 (0.06) | 26 / 45 | 0.51 (0.07) | 0.44 (0.07) | 0.0501 |

| Post | 93 / 176 | 0.58 (.04) | 0.50 (.04) | 66 / 119 | 0.54 (0.05) | 0.45 (0.05) | 46 / 80 | 0.47 (0.06) | 0.41 (0.06) | 0.3726 |

| PR | ||||||||||

| Negative | 82 / 158 | 0.55 (0.04) | 0.50 (0.04) | 49 / 81 | 0.49 (0.06) | 0.41 (0.06) | 33 / 51 | 0.37 (0.07) | 0.37 (0.07) | 0.0586 |

| Positive | 67 / 134 | 0.67 (0.04) | 0.56 (0.04) | 40 / 75 | 0.60 (0.06) | 0.48 (0.06) | 34 / 66 | 0.57 (0.06) | 0.47 (0.06) | 0.7207 |

| Number of lymph nodes positive | ||||||||||

| 1–3 | 74 / 184 | 0.70 (0.03) | 0.63 (0.04) | 39 / 92 | 0.67 (0.05) | 0.60 (0.05) | 21 / 53 | 0.66 (0.07) | 0.62 (0.07) | 0.8620 |

| 4–9 | 62 / 103 | 0.54 (0.05) | 0.42 (0.05) | 43 / 57 | 0.41 (0.07) | 0.27 (0.06) | 24 / 42 | 0.52 (0.08) | 0.38 (0.08) | 0.1864 |

| 10+ | 31 / 43 | 0.41 (0.08) | 0.31 (0.07) | 24 / 31 | 0.35 (0.09) | 0.22 (0.08) | 25 / 28 | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.0119 |

BMI, body mass index; PR, progesterone receptor.

Normal: BMI <25; Overweight: 25≤BMI<30; Obese: BMI ≥30;

premenopausal;

postmenopausal.

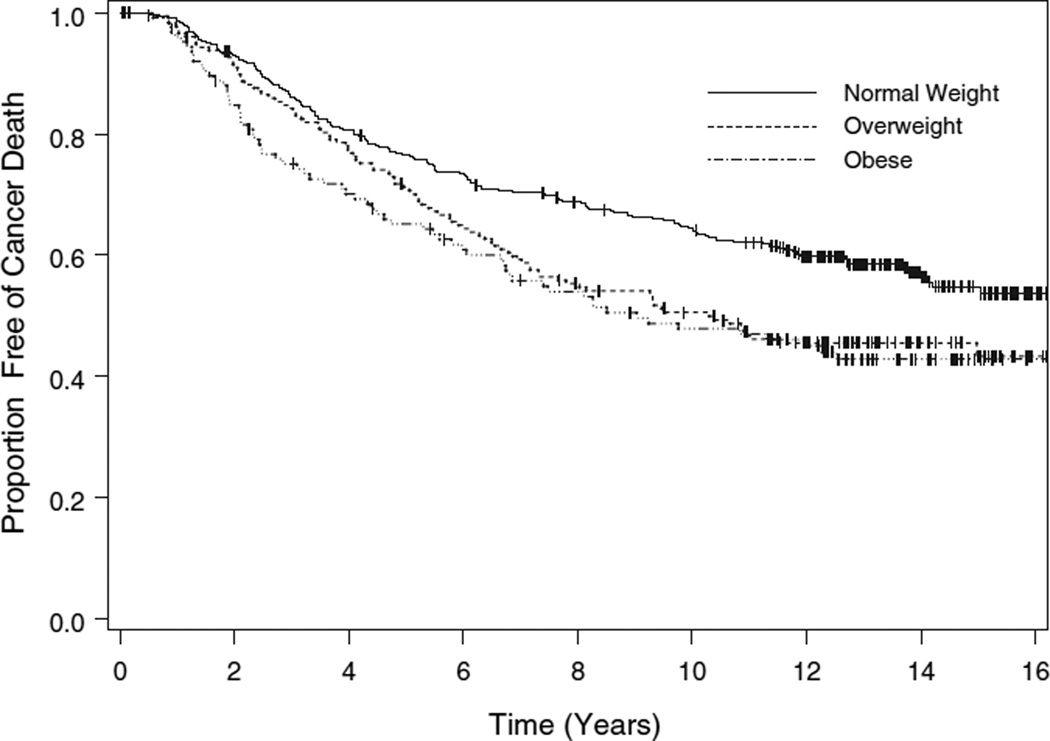

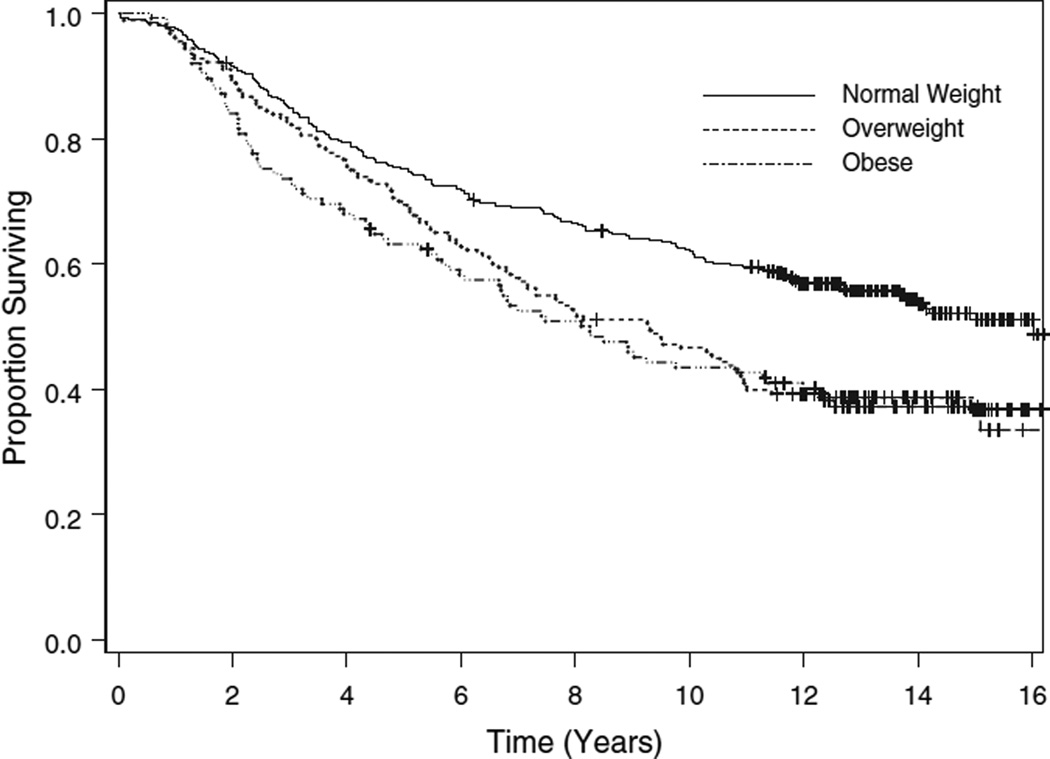

Survival

We also examined the effect of BMI on survival, evaluating both mortality because of breast cancer (censoring those deaths due to causes other than breast cancer) and all-cause mortality. The median time to death from breast cancer had not been reached for the normal weight women, and was 10.3 years for those who were overweight, and 9.0 years for those who were obese (p = 0.0025, logrank test, Fig. 2). The overall median survival time was 16.0 years for the normal weight women, 9.3 years for the overweight women, and 8.3 years for those who were obese (p = 0.0001, logrank test, Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Cancer survival by body mass index category. For this outcome, deaths because of causes other than cancer are treated as censored observations.

Figure 3.

Overall survival by body mass index category. For this outcome, deaths from any cause are treated as events.

In the univariate analysis, BMI considered continuously was significantly associated with cancer death (p = 0.0009). The risk of cancer death increased by 4% for every kg / m2 increase in BMI. Additionally, number of involved lymph nodes (p < 0.0001), ER status (p = 0.0287), and PR status (p = 0.0002) were significantly associated with the risk of cancer death. Women with fewer involved lymph nodes and those having ER+ and PR+ tumors fared better. The other factors considered were not univariately associated with death from cancer.

In the multivariable analysis, the two-way interactions between BMI and age (p = 0.0033), BMI and involved lymph nodes (p = 0.0086), and BMI and PR status (p = 0.0277) were statistically significant. The effect of BMI was stronger for younger women, those with more involved lymph nodes, and those with PR tumors, with a higher baseline BMI associated with an increased risk of cancer death. Five and ten-year estimates for cancer survival are shown in Table 5 by BMI category for selected subgroups of women, illustrating the findings of the multivariable analysis.

Table 5.

Cancer Survival by BMI category* for Selected Subgroups of Women

| Normal |

Overweight |

Obese |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Events / n | 5 years | 10 years | Events / n | 5 years | 10 years | Events / n | 5 years | 10 years | p-value |

| Total | 138 / 330 | 0.77 (0.02) | 0.64 (0.03) | 96 / 180 | 0.71 (0.03) | 0.50 (0.04) | 69 / 125 | 0.65 (0.04) | 0.48 (0.05) | 0.0025 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤41 | 32 / 75 | 0.80 (0.05) | 0.61 (0.06) | 11 / 22 | 0.86 (0.07) | 0.63 (0.10) | 12 / 15 | 0.53 (0.13) | 0.33 (0.12) | 0.0141 |

| 42–53† | 29 / 79 | 0.83 (0.04) | 0.72 (0.05) | 24 / 39 | 0.72 (0.07) | 0.44 (0.08) | 14 / 30 | 0.73 (0.08) | 0.59 (.09) | 0.0313 |

| 42–53‡ | 15 / 41 | 0.73 (0.07) | 0.65 (0.08) | 16 / 23 | 0.48 (0.10) | 0.35 (0.10) | 13 / 21 | 0.47 (0.11) | 0.35 (0.11) | 0.0277 |

| ≥54 | 62 / 135 | 0.72 (0.04) | 0.62 (0.04) | 45 / 96 | 0.73 (0.05) | 0.54 (0.05) | 30 / 59 | 0.71 (0.06) | 0.50 (0.07) | 0.7442 |

| Menopause | ||||||||||

| Pre | 61 / 154 | 0.82 (0.03) | 0.67 (0.04) | 35 / 61 | 0.77 (0.05) | 0.51 (0.06) | 26 / 45 | 0.67 (0.07) | 0.51 (0.08) | 0.0147 |

| Post | 77 / 176 | 0.72 (0.03) | 0.62 (0.04) | 61 / 119 | 0.68 (0.04) | 0.51 (0.05) | 43 / 80 | 0.64 (0.05) | 0.46 (0.06) | 0.1558 |

| PR | ||||||||||

| Negative | 74 / 158 | 0.68 (0.04) | 0.58 (0.04) | 48 / 81 | 0.65 (0.05) | 0.45 (0.06) | 33 / 51 | 0.51 (0.07) | 0.35 (0.07) | 0.0092 |

| Positive | 47 / 134 | 0.82 (0.03) | 0.71 (0.04) | 35 / 75 | 0.77 (0.05) | 0.58 (0.06) | 31 / 66 | 0.77 (0.05) | 0.59 (0.06) | 0.1517 |

| Number of lymph nodes positive | ||||||||||

| 1–3 | 57 / 184 | 0.84 (0.03) | 0.75 (0.03) | 37 / 92 | 0.78 (0.04) | 0.62 (0.05) | 21 / 53 | 0.81 (0.05) | 0.63 (0.07) | 0.2357 |

| 4–9 | 52 / 103 | 0.71 (0.05) | 0.55 (0.05) | 37 / 57 | 0.66 (0.06) | 0.39 (0.07) | 22 / 42 | 0.70 (0.07) | 0.53 (0.08) | 0.1831 |

| 10+ | 29 / 43 | 0.60 (0.08) | 0.40 (0.08) | 22 / 31 | 0.61 (0.09) | 0.37 (0.09) | 24 / 28 | 0.32 (0.09) | 0.14 (0.07) | 0.0189 |

BMI, body mass index; PR, progesterone.

Normal: BMI <25; Overweight: 25 ≤BMI<30; Obese: BMI ≥30;

premenopausal;

postmenopausal.

Body mass index, considered continuously (p = 0.0001), the number of involved lymph nodes (p < 0.0001), PR status (p = 0.0006), menopausal status (p = 0.0184), and age (p = 0.0334) were univariately associated with overall survival. The risk of death increased by 4% for every kg / m2 increase in BMI. A greater number of involved lymph nodes, PR disease, menopause, and older age were negative risk factors. In the multivariable analysis, the two-way interactions between BMI and age (p = 0.0104), BMI and nodes positive (p = 0.0145), and BMI and PR status (p = 0.0189) were statistically significant. The effect of BMI was stronger for younger women, those with more involved lymph nodes, and those with PR tumors, with a higher baseline BMI associated with an increased risk of death. Five and ten-year survival estimates are shown in Table 6 by BMI category for selected subgroups of women, again illustrating the multivariable results.

Table 6.

Overall Survival by BMI category* for Selected Subgroups of Women

| Normal |

Overweight |

Obese |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Events / n | 5 years | 10 years | Events / n | 5 years | 10 years | Events / n | 5 years | 10 years | p-value |

| Total | 151 / 330 | 0.75 (0.02) | 0.62 (0.03) | 111 / 180 | 0.69 (0.03) | 0.47 (0.04) | 79 / 125 | 0.63 (0.04) | 0.43 (0.04) | 0.0001 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤41 | 33 / 75 | 0.80 (0.05) | 0.61 (0.06) | 13 / 22 | 0.86 (0.07) | 0.59 (0.10) | 12 / 15 | 0.53 (0.13) | 0.33 (0.12) | 0.0242 |

| 42–53† | 31 / 79 | 0.82 (0.04) | 0.70 (0.05) | 24 / 39 | 0.72 (0.07) | 0.44 (0.08) | 15 / 30 | 0.73 (0.08) | 0.56 (0.09) | 0.0511 |

| 2–53‡ | 16 / 41 | 0.73 (0.07) | 0.65 (0.08) | 17 / 23 | 0.48 (0.10) | 0.35 (0.10) | 15 / 21 | 0.43 (0.11) | 0.29 (0.10) | 0.0108 |

| ≥54 | 71 / 135 | 0.69 (0.04) | 0.58 (0.04) | 57 / 96 | 0.70 (0.05) | 0.48 (0.05) | 37 / 59 | 0.68 (0.06) | 0.45 (0.07) | 0.3958 |

| Menopause | ||||||||||

| Pre | 64 / 154 | 0.81 (0.03) | 0.66 (0.04) | 37 / 61 | 0.77 (0.05) | 0.49 (0.06) | 27 / 45 | 0.67 (0.07) | 0.48 (0.08) | 0.0110 |

| Post | 87 / 176 | 0.70 (0.03) | 0.59 (0.04) | 74 / 119 | 0.66 (0.04) | 0.45 (0.05) | 52 / 80 | 0.61 (0.05) | 0.41 (0.06) | 0.0288 |

| PR | ||||||||||

| Negative | 78 / 158 | 0.67 (0.04) | 0.56 (0.04) | 55 / 81 | 0.64 (0.05) | 0.41 (0.05) | 36 / 51 | 0.49 (0.07) | 0.33 (0.07) | 0.0019 |

| Positive | 54 / 134 | 0.81 (0.03) | 0.68 (0.04) | 40 / 75 | 0.76 (0.05) | 0.55 (0.06) | 38 / 66 | 0.74 (0.05) | 0.53 (0.06) | 0.0595 |

| Number of lymph nodes positive | ||||||||||

| 1–3 | 66 / 184 | 0.82 (0.03) | 0.73 (0.03) | 42 / 92 | 0.76 (0.04) | 0.60 (0.05) | 5 / 53 | 0.81 (0.05) | 0.60 (0.07) | 0.1741 |

| 4–9 | 55 / 103 | 0.70 (0.05) | 0.53 (0.05) | 43 / 57 | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.37 (0.06) | 28 / 42 | 0.64 (0.07) | 0.44 (0.08) | 0.0457 |

| 10+ | 30 / 43 | 0.58 (0.08) | 0.40 (0.07) | 26 / 31 | 0.58 (0.09) | 0.26 (0.08) | 24 / 28 | 0.32 (0.09) | 0.14 (0.07) | 0.0302 |

BMI, body mass index; PR, progesterone.

Normal: BMI <25; Overweight: 25 ≤BMI≤ 30; Obese: BMI ≥30;

premenopausal;

postmenopausal.

DISCUSSION

In this secondary analysis of a large prospective Phase II trial of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with stage II-III, lymph node positive breast cancer, we found that BMI was significantly associated with recurrence, death from cancer, and death from any cause. For all outcomes, the effect of BMI was modified by PR status, number of involved lymph nodes, and age. For women who had PR breast cancer, a higher BMI was predictive of a shorter time to relapse and a shorter survival, particularly for younger women and women with multiple involved lymph nodes. The effect of BMI on recurrence in women with PR+ breast cancer was less clear. For this subgroup, a higher BMI was predictive of a longer time to recurrence and survival for older women with few involved lymph nodes and it was only moderately predictive of a decreased time to recurrence and survival for those women with a large number of involved lymph nodes (≥10), this latter association being stronger in younger women. This result in women with PR+ tumors was similar to that reported by Dignam 2003 (17) who found no association between BMI and recurrence in women with ER+, node-negative breast cancer. These results are also similar to those reported by Suissa 1989 (18), who noted a curvilinear relationship between recurrence risk and BMI, such that very thin and very heavy women were at increased risk. A quadratic term for BMI in women with PR+ breast cancer in our study was of borderline significance (p = 0.1996). Additionally, den Tonkelaar 1995 (19) noted that obese women with ER+ breast cancer had better survival than nonobese women. In contrast is the study of Maehle 1996 (20), who found that a higher BMI was associated with decreased survival in women with receptor-positive cancer but an increased survival in women with receptor-negative cancer.

We also observed that BMI was an even stronger predictor of disease-free and overall survival in those patients with a greater number of positive nodes. This is in contrast to findings by Donegan 1978 (21), Boyd 1981 (22), and Newman 1997 (23), all of whom noted a stronger relationship between BMI and prognosis in women without lymph node involvement than those with involved lymph nodes. Those studies just looked at those without lymph node involvement versus those with breast cancer with involved lymph nodes. Tartter 1981 (24) found that the effect of obesity on disease-free survival was stronger in patients with more advanced tumors (i.e., higher stage disease). These investigators did not evaluate the number of involved lymph nodes within a stage. It is possible that our findings regarding the number of positive lymph nodes reflects some degree of misclassification such that the number of involved lymph nodes is more likely to be underestimated in obese women or perhaps obese women with a greater number of involved lymph nodes are more likely to be staged incorrectly.

We also found that BMI has a greater effect on prognosis in younger women. For older postmenopausal women, there is little association between BMI and prognosis. We noted that the best prognosis was for older premenopausal women. Younger premenopausal and younger postmenopausal women had the worst prognosis. Our findings contrast those of Kimura 1990 (25) and Haybittle 1997 (26), who noted that the relationship between weight and survival was much stronger in postmenopausal women. However, our findings coincide with those of Lees 1989 (27) and Hebert 1998 (28), who found that the relationship between weight and prognosis was stronger in premenopausal women.

Multiple explanations might account for the relationship between BMI and prognosis. Biological mechanisms, as discussed in the introduction, have been proposed to explain the relationship between body fat and breast cancer. Excess body fat has been shown to increase estrogen production and stimulate cell proliferation in ER+ tumor cells. It has also been reported that visceral fat distribution increases insulin resistance, predisposing to hyperinsulinemia, glucose intolerance, dyslipidemias, and hypertension. Hyperinsulinemia raises plasma levels of the free form of immunoglobulin factor-1, a stimulatory hormone of cancerous cell growth, although precise mechanisms need to be further investigated. BMI is also a proxy for several factors including low physical activity, high calorie intake, and body fat tissue. As data related to those factors were not collected from this study population, additional study is warranted to elucidate the role of those factors in recurrence and survival. Finally, chemotherapy doses were capped at a BSA of 2 m2, so it is possible that some of the doses given to obese women were inadequate.

While we have focused on the role of BMI and its interactions with other characteristics, we also noted that the number of lymph nodes examined was significantly associated with recurrence and borderline significantly associated with overall survival; women with fewer lymph nodes examined had a faster time to recurrence and decreased survival. They may represent misclassification in that we could have underestimated the number of positive lymph nodes in women with fewer axillary nodes examined. Lethaby 1996 (29) and van der Wal 2002 (30) noted similar results in women with breast cancer without lymph node involvement. However, the latter researchers found that for women with lymph node involvement, the number of lymph nodes removed was positively associated with mortality. However, in their statistical model, the number of involved lymph nodes was included as a main effect and as a denominator in the ratio of invaded to removed lymph nodes, so the interpretation of the main effect is somewhat confusing.

Several limitations warrant discussion. This was a single arm study; we therefore cannot tell if the effect of BMI would be the same in patients without therapy (although the bulk of evidence supports the notion that BMI is a prognostic factor in patients without therapy) or in patients receiving other therapies, or if BMI influences the effectiveness of therapy. All women with ER+ tumors received tamoxifen, thus we cannot tease out whether differences (or lack of differences) based on receptor status are because of the receptors or the tamoxifen. However, tamoxifen was only given for half a year, so it is likely that it did not have a major impact on the results. We only have baseline BMI measurements. The study was not designed to assess the effect of weight gain or loss over time (before or after diagnosis) on risk. No measures of body composition were collected. Some other investigators [e.g., Jain and Miller (31) and Borugian et al. (32)] found that measures such as higher triceps, skinfold thickness, or waist-hip ratio were more strongly associated with prognosis than BMI. It is likely that tissue quality plays an important role in recurrence, whereby women who have more adipose tissue are at higher risk of recurrence than women of the same weight but composed more of lean tissue.

Despite its limitations, this study provides important data on the role of BMI on prognosis in women with stage II, node-positive breast cancer treated in a uniform manner. We found that BMI plays an important role in relation to recurrence and survival following surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II breast cancer and that the relationship is stronger for receptor-negative women, younger women, and women with more involved lymph nodes.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants P30-CA-12197 and U10-CA-81851 from the Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaye SA, Folsom AR, Soler JT, Prineas RJ, Potter JD. Associations of body mass and fat distribution with sex hormone concentrations in postmenopausal women. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:151–156. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu H, Rohan T. Role of the insulin-like growth factor family in cancer development and progression. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1472–1489. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.18.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Manson JE, et al. Alcohol, height, and adiposity in relation to estrogen and prolactin levels in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1297–1302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.17.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siiteri PK. Adipose tissue as a source of hormones. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:277–282. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein L, Ross RK. Endogenous hormones and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:48–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selby C. Sex hormone binding globulin: origin, function, and clinical significance. Ann Clin Biochem. 1990;27:532–541. doi: 10.1177/000456329002700603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin PJ, Boyd NF. Body size and breast cancer prognosis: a critical review of the evidence. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1990;16:205–214. doi: 10.1007/BF01806329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryu SY, Kim CB, Nam CM, et al. Is body mass index the prognostic factor in breast cancer? A meta-analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:610–614. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.5.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chlebowski RT, Aiello E, McTiernan A. Weight loss in breast cancer patient management. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1128–1143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimmick GG, Shelton BJ, Case LD, Cooper MR, Muss HB. Long-term follow-up of a phase II trial studying a weekly doxorubicin-based multiple drug adjuvant therapy for stage II node-positive carcinoma of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;72:233–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1014953407098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables (with discussion) J Royal Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. NIH Publication Number 98–4083. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1998. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Over-weight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM, Fleming TR. Martingale based residuals for survival models. Biometrika. 1990;77:147–160. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dignam JJ, Wieand K, Johnson KA, Fisher B, Xu L, Mamounas EP. Obesity, tamoxifen use, and outcomes in women with estrogen receptor positive early stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1467–1476. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suissa S, Pollak M, Spitzer WO, Margolese R. Body size and breast cancer prognosis: a statistical explanation of the discrepancies. Cancer Res. 1989;49:3113–3116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.den Tonkelaar I, de Waard F, Seidell JC, Fracheboud J. Obesity and subcutaneous fat patterning in relation to survival of postmenopausal breast cancer patients participating in the DOM project. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;34:129–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00665785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maehle BO, Tretli S. Pre-morbid body mass index in breast cancer: reversed effect on survival in hormone receptor negative patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;41:123–130. doi: 10.1007/BF01807157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donegan WL, Hartz AJ, Rimm AA. The association of body weight with recurrent cancer of the breast. Cancer. 1978;41:1590–1594. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197804)41:4<1590::aid-cncr2820410449>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyd NF, Campbell JE, Germanson T, Thomson DB, Sutherland DJ, Meakin JW. Body weight and prognosis in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;67:785–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman SC, Lees AW, Jenkins HJ. The effect of body mass index and oestrogen receptor level on survival of breast cancer patients. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:484–490. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tartter PI, Papatestas AE, Ioannovich J, Mulvihill MN, Lesnick G, Aufses AH., Jr Cholesterol and obesity as prognostic factors I breast cancer. Cancer. 1981;47:2222–2227. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810501)47:9<2222::aid-cncr2820470919>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura M. Obesity as prognostic factors in breast cancer. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1990;10:S247–S251. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(90)90171-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haybittle J, Houghton J, Baum M. Social class and weight as prognostic factors in early breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:729–733. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lees AW, Jenkins HJ, May CL, Cherian G, Lam EW, Hanson J. Risk factors and 10-year breast cancer survival in northern Alberta. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1989;13:143–151. doi: 10.1007/BF01806526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hebert JR, Hurley TG, Ma Y. The effect of dietary exposures on recurrence and mortality in early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;51:17–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1006056915001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lethaby AE, Mason BH, Harvey VJ, Holdaway IM. Survival of women with node negative breast cancer in the Auckland region. N Z Med J. 1996;109:330–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Wal BC, Butzelaar RM, van der Meij S, Boermeester MA. Axillary lymph node ratio and total number of removed lymph nodes: predictors of survival in stage I and II breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:481–489. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain M, Miller AB. Pre-morbid body size and the prognosis of women with breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1994;59:363–368. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910590312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borugian MJ, Sheps SB, Kim-Sing C, et al. Waist-to-hip ratio and breast cancer mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:963–968. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]