Abstract

We report a challenging case of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (multiple etiologic factors) that was complicated by heparin resistance secondary to suspected antithrombin III (ATIII) deficiency. A 20-year-old female previously healthy and currently 8 weeks pregnant presented with worsening headaches, nausea, and decreasing Glasgow Coma Scale/Score (GCS), necessitating mechanical ventilatory support. Imaging showed extensive clots in multiple cerebral venous sinuses including the superior sagittal sinus, transverse, sigmoid, jugular veins, and the straight sinus. She was started on systemic anticoagulation and underwent mechanical clot removal and catheter-directed endovascular thrombolysis with limited success. Complicating the intensive care unit care was the development of heparin resistance, with an inability to reach the target partial thomboplastin time (PTT) of 60 to 80 seconds. At her peak heparin dose, she was receiving >35 000 units/24 h, and her PTT was subtherapeutic at <50 seconds. Deficiency of ATIII was suspected as a possible etiology of her heparin resistance. Fresh frozen plasma was administered for ATIII level repletion. Given her high thrombogenic risk and challenges with conventional anticoagulation regimens, we transitioned to argatroban for systemic anticoagulation. Heparin produces its major anticoagulant effect by inactivating thrombin and factor X through an AT-dependent mechanism. For inhibition of thrombin, heparin must bind to both the coagulation enzyme and the AT. A deficiency of AT leads to a hypercoagulable state and decreased efficacy of heparin that places patients at high risk of thromboembolism. Heparin resistance, especially in the setting of critical illness, should raise the index of suspicion for AT deficiency. Argatroban is an alternate agent for systemic anticoagulation in the setting of heparin resistance.

Keywords: stroke, cerebrovascular disorders, hematology, clinical specialty, neurocritical care, clinical specialty

Introduction

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is a rare disorder with an annual incidence estimated to be 3 to 4 cases per million and accounting for only about 0.5% of all patients presenting with stroke-like symptoms.1 We report a challenging clinical course of a case of CVST complicated by heparin resistance secondary to a suspected etiology of antithrombin III (ATIII) deficiency.

Case Report

After obtaining institutional review board approval and consent from the patient’s family, we describe a 20-year-old female who presented with worsening headaches and nausea for the past several days. In the emergency department, she had an acute decrease in mental status likely secondary to worsening cerebral edema (seen on the computed tomography scan on admission) that required intubation and mechanical ventilatory support. She was in her eighth week of pregnancy at the time of admission. On admission imaging, she was found to have extensive clots in multiple dural venous sinuses including the superior sagittal sinus, transverse, sigmoid, jugular veins, and straight sinus (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) of the brain showing extensive cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) involving the numbered structures: (1) sigmoid sinus, (2) transverse sinus, (3) straight sinus, and (4) superior sagittal sinus.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (gradient echo sequence) showing thrombosis of occipital portion of the superior sagittal sinus and extensive thrombosis of the cortical veins.

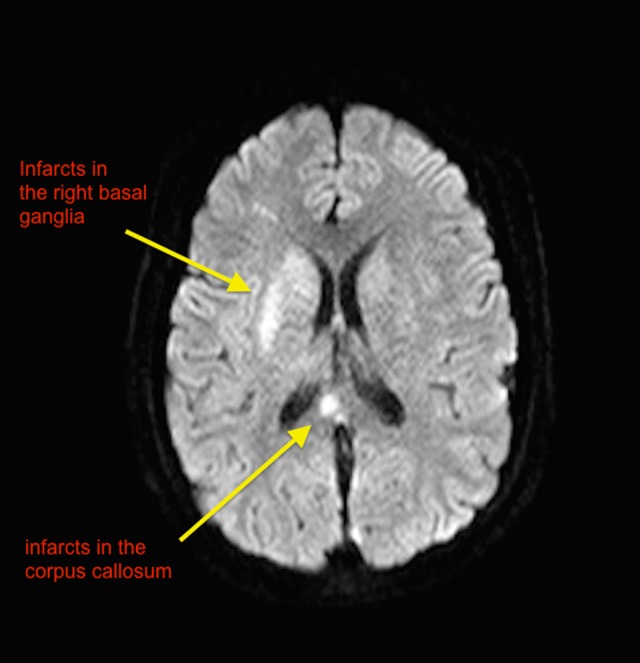

Figure 3.

Multiplanar multisequence Magnetic resonance imaging without intravenous contrast. MRV was completed using 3-dimensional (3D) phase-contrast technique without IV contrast. Scan showing extensive cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) and new infarcts in the basal ganglia and corpus callosum.

The clot burden and cerebral edema seen on admission imaging in this young pregnant patient with a deteriorating neurological examination prompted the decision to attempt mechanical thrombectomy. She was started on systemic anticoagulation with heparin prior to the procedure. The intraoperative angiogram showed the extensive sinus thrombosis and evidence of venous hypertension due to outflow restriction. The surgical team removed clot fragments from multiple venous sinuses. Complete clot retrieval was not possible, and the surgeons felt that the clots were extremely friable and not safely retrievable mechanically. Attempts combined with focused catheter-directed thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) resulted in limited recanalization of the bilateral transverse sinuses and sigmoid sinus. She was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) intubated and sedated. The neurosurgical team deferred the placement of an intracranial pressure monitor secondary to the risk of bleeding in the setting of exposure to tPA and systemic anticoagulation. Goals of care discussion on admission to the ICU, with the family, helped establish the priority to save the mother.

In the ICU, despite escalating doses of heparin, we were unable to reach the target partial thomboplastin time (PTT) of 60 to 80 seconds for more than 36 hours. At her peak heparin dose, she was receiving 2500 units/h and her PTT was <50 seconds.

Antithrombin III deficiency was high on the differential diagnosis of heparin resistance. Fresh frozen plasma was administered for repleting ATIII levels, and this made her PTT therapeutic for a short period of time. The first therapeutic PTT was achieved after almost 36 hours after starting the heparin infusion on an aggressive protocol.

Interestingly, her post-fresh frozen plasma (post-FFP) transfusion ATIII level was only 64% (normal 80%-120%). Given her high thrombogenic risk, high risk of clinical deterioration in the absence of effective systemic anticoagulation and challenges with conventional anticoagulation regimens, we transitioned her to a direct thrombin inhibitor—argatroban for systemic anticoagulation.

We achieved our target PTT in less than 24 hours after on argatroban. The patient’s neurologic examination rapidly improved. In spite of developing areas of venous infarcts (Figure 3), she was successfully extubated and was subsequently discharged from the hospital with a viable pregnancy.

Discussion

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis continues to be a rare but potentially intervenable cause of stroke in the younger (<50 years) patient population. Early diagnosis and restoration of blood flow is key to a good outcome. Systemic anticoagulation is the current standard of care. The current duration of anticoagulation is dictated by the underlying etiology, and patients are treated with lifelong anticoagulation when CVST is associated with an inborn error of metabolism such as methyl tetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency leading to a hypercoagulable state.2 The aims of antithrombotic treatment in CVST are (1) recanalization of the occluded sinus/vein, (2) decrease in the risk of clot extension, and (3) to treat the underlying prothrombotic state. The mechanism of cerebral dysfunction post-CVST is primarily due to venous cerebral infarction and or intracranial hypertension due to increased venous pressure and impaired CSF dynamics. Smaller case series using interventional devices and techniques such as the AngioJet device (Medrad Inc, Pennsylvania), Penumbra system (Penumbra Inc, California), clot retraction with a microsnare balloon venoplasty, and so on have been described. There has not been a sufficiently powered randomized trial to compare mechanical thrombolysis with systemic anticoagulation for CVST.3,4

Anticoagulants with bodyweight-adjusted subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or dose-adjusted intravenous heparin are widely used as first-line therapy on the basis of 3 randomized trials, a meta-analysis, and numerous large open series such as the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT) trial.1 Heparin is a negatively charged glycosaminoglycan that exerts its anticoagulation by activating AT. Antithrombin III is a vitamin K-independent glycoprotein that serves as a major inhibitor of thrombin.

The heparin chain with anticoagulant activity contains a critical pentasaccharide sequence that houses the high affinity-binding site for AT. This sequence occurs in only about one-third of heparin chains and is randomly distributed. The heparin–antithrombin complex then inactivates thrombin, activated factor X, and other activated clotting factors. Binding of heparin to ATIII catalyzes the inactivation of thrombin by ATIII.5

Normal AT activity levels are expressed as a percentage and are in the 80% to 120% range. Therapy to replenish ATIII levels in the setting of thromboembolic disease is initiated when the levels drop below 80%. Acquired ATIII deficiency is frequently a result of a consumptive processes such as disseminated intravascular coagulation, microangiopathic hemolytic anemias, and hemolytic–uremic syndrome.

In patients with heparin resistance, consideration may be given to checking ATIII levels, especially when heparin resistance is associated with recurrent or progressive thrombosis.6 Exogenously infused ATIII can provide a rapid mechanism to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation targets. This can be achieved in 2 ways: by transfusing FFP (which contains ATIII)7 or alternately giving recombinant ATIII where available. Administration of FFP carries the risks of transfusion reactions, transfusion-related acute lung injury, and fluid overload.

Heparin resistance is defined as the need for more than 35 000 units in a 24-hour period to prolong activated PTT in the therapeutic range.8 Heparin resistance occurs in up to 22% of patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass, and 65% of these cases are secondary to ATIII deficiency.9 Other reasons for heparin resistance include increased heparin clearance and or elevation in heparin-binding proteins.5 Many heparin-binding proteins are acute-phase reactants, and heparin resistance can be encountered in acutely ill patients and during peri- or postpartum periods. The precise mechanism of heparin resistance in our specific patient was unclear but was likely the result of a combination of factors. In our specific case, the challenges of achieving timely therapeutic anticoagulation combined with clinical signs of increased cerebral venous congestion prompted us to explore other anticoagulant options.

Argatroban is an arginine-based synthetic direct thrombin inhibitor (selectively and reversibly binds to the active site of thrombin) and has a half-life of about 40 minutes and primarily eliminated by hepatic metabolism. The US Food and Drug Administration classifies argatroban as a category B drug in pregnancy (ie, animal studies have failed to reveal evidence of fetal harm. There are no controlled data in human pregnancy). There are several case reports detailing the successful use of argatroban in pregnancy. It has best been studied as the anticoagulant in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and has been shown to decrease thrombotic events without an increase in bleeding complications.10 Argatroban can be a viable alternative when the clinical and laboratory pictures of heparin resistance are unclear.

Conclusion

Heparin resistance, especially in the setting of critical illness, should raise the index of suspicion for ATIII deficiency. Alternate systemic anticoagulants should be considered early if therapeutic anticoagulation cannot be achieved in a timely manner. Prompt recognition and aggressive ICU and interventional management led to a good outcome in our patient.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Study design, data collection, and manuscript preparation were done by ABK AK, and AOD; Data analysis, interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation were done by CB, AOD, and ABK; AND Approval of final manuscript was done by ABK, AK, and AOD.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Departmental funds only.

References

- 1. Bousser MG, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coutinho J, de Bruijn SF, Deveber G, Stam J. Anticoagulation for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD002005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saadatnia M, Fatehi F, Basiri K, Mousavi SA, Mehr GK. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis risk factors. Int J Stroke. 2009;4(2):111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dentali F, Squizzato A, Gianni M, et al. Safety of thrombolysis in cerebral venous thrombosis. A systematic review of the literature. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(5):1055–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hirsh J, Bauer KA, Donati MB, et al. Parenteral anticoagulants: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 suppl):141S–159S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McRae SJ, Ginsberg JS. Initial treatment of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2004;110(9 suppl 1):I–3–I–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beattie GW, Jeffrey RR. Is there evidence that fresh frozen plasma is superior to antithrombin administration to treat heparin resistance in cardiac surgery? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18(1):117–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anderson JAM, Saenko EL., Editorial I: heparin resistance. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88(4):467–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spiess BD. Treating heparin resistance with antithrombin or fresh frozen plasma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(6):2153–2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dasararaju R, Singh N, Mehta A. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: review. Expert Rev Hematol. 2013;6(4):419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]