Abstract

Early mitotic inhibitor-1 (Emi1), as a key cell cycle regulatory gene, induces S phase and mitotic entry by controlling anaphase-promoting complex substrates. Emi1 overexpression may be a prognostic factor for patients with invasive breast cancer. However, its expression and clinical significance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) remain unknown. In the present study, Emi1 was overexpressed in ESCC samples, contrarily to their neighboring normal tissues. The expression of Emi1 was correlated with histological differentiation (P=0.032), lymphatic metastasis (P=0.006) and Ki-67 expression (P=0.028). Multivariate analysis indicated that the presence of lymphatic metastasis and the protein expression levels of Emi1 and Ki-67 were all independent prognostic factors for ESCC patients (P=0.042, 0.018 and 0.001, respectively). In vitro, however, the expression of Emi1 was upregulated in the ECA109 cell line following release from serum starvation. In addition, depletion of endogenous Emi1 by small interfering RNA could effectively reduce cell proliferation. Thus, the present data indicated that Emi1 expression was upregulated in ESCC tissues and correlated with poor survival in ESCC patients, and suggested that Emi1 may be an independent prognostic factor for ESCC patients.

Keywords: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, early mitotic inhibitor-1, prognosis

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC), the eighth most common type of cancer in the world, may be pathologically divided into two major categories: Esophageal adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) (1,2). In China, EC is highly prevalent, and is the fourth-ranked cancer in terms of incidence (3). Due to the difficulties in early diagnosis and poor treatment efficacy, the 5-year survival rate of ESCC is considerably low, ranging from 15–25% (1–4). Thus far, numerous studies have been conducted to attempt to clarify the fundamental molecular mechanisms and biological behavior of ESCC.

Abnormalities in the cell cycle are essential in the process of human carcinogenesis, resulting in an increase in cell proliferation and/or a reduction in the death of abnormal cells (5). Several key proteins are required to maintain the integrity of the normal cell cycle, and aberrant expression of proteins such as cyclins A and B1 leads to an abnormal cell cycle (5–8). Cyclin A, as an important checkpoint mechanism in the G1-S transition of the cell cycle, is expressed just prior to the start of DNA synthesis, while cyclin B1 acts as a mitotic cyclin protein in the G2-M transition (9). It has been verified that the expression of cyclin A and cyclin B1 is remarkably upregulated in human ESCC, as opposed to neighboring normal tissues (10,11). Therefore, cyclins A and B1 may be implicated in the tumorigenesis and evolution of malignancies (9–13). Early mitotic inhibitor-1 (Emi1), as a cell cycle regulator, governs the progression to S phase and mitosis by stabilizing key ubiquitination substrates of anaphase-promoting complex, including cyclins A and B1 (14–16). It has been previously reported that excess Emi1 added to Xenopus egg extracts prevents cyclins A and B1 degradation, and is required for accumulation of cyclins A and B1 (17). In addition, upregulation of Emi1 messenger RNA exists in numerous malignant tumors, and its overexpression produces mitotic defects, possibly resulting in tumorigenesis (18–20).

Despite the frequent dysfunction of the cell cycle machinery in human ESCC, the expression and clinical significance of Emil protein in ESCC remain unclear. In the present study, Emi1 protein expression was determined by immunohistochemistry and immunoblotting in ESCC, and the associations between Emi1 and clinicopathological variables and prognosis were investigated. In addition, ECA109 cells were transfected with Emi1 small interfering (si)RNA vectors in vitro to investigate the functionality of Emi1 as a potential therapeutic target for ESCC.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue specimens

In the present study, 90 ESCC (55 males and 35 females) aged 31–80 years (mean, 60 years) were retrieved from the archival files of the Department of Pathology of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (Nantong, China) from January 2000 to December 2004. None of the patients were treated with radiation, chemotherapy or immunotherapy prior to operation. Upon signing informed consent, patients were questioned regarding their demographic characteristics. Histological differentiation was divided into three grades, namely, grade I (well differentiated), II (moderately differentiated) and III (poorly differentiated). The 90 patients examined were grouped into the above three grades (20 patients into grade I, 50 into grade II and 20 into grade III). In addition, invasion of lymphatic and blood vessels was evaluated microscopically.

Tissue specimens were treated as soon as surgical removal was completed. For histological examination, all tumorous and para-cancerous tissue portions were processed into 10% buffered formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks. Protein expression was analyzed in 8 tumorous and para-cancerous tissue samples stored at −80°C.

Immunohistochemical analyses

The tissue sections were deparaffinized through a graded ethanol series, and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersion in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Next, the sections were treated in 10 mmol/l citrate buffer (pH 6.0; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), and heated to 121°C in a pressure cooker for 20 min for antigen retrieval. Upon washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2), 10% goat serum (Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was applied for 1 h at room temperature to block nonspecific reactions. Then, the sections were incubated for 12 h at 4°C with anti-Emi1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100; cat. no. sc-30182; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), and anti-Ki-67 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:100; clone 7B11; Zymed; cat. no. MA5-15690; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Negative control sections were also processed in parallel with a nonspecific immunoglobulin (Ig)G (cat. no. I5006-10MG; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) applied at the same concentration as the above primary antibodies. All sections were treated using the peroxidase-antiperoxidase method (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Upon washing in PBS, the peroxidase reaction was visualized by incubating the slides with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride in 0.05 mol/l Tris buffer (pH 7.6) including 0.03% H2O2. Upon washing in water, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in a graded alcohol series and coverslipped.

Immunohistochemical evaluation

All the immunostained sections were assessed in a blinded approach without knowing the patients' clinical and pathological variables. Regarding Emil assessment, staining intensity was evaluated using a four rating-level-scheme, where scores ranging from 0 to 3 indicated negative, weak, medium and strong staining, respectively. For extent of staining, a five rating-level-scheme was employed. Thus, based on the total amount of positive stained areas in the whole carcinoma region, the extent of staining was evaluated with scores ranging from 0 to 4 as follows: 0, 0%; 1, 1–25%; 2, 26–50%; 3, 51–75%; and 4, 76–100%. The sum of intensity and extent scores was used as the final staining score (0–7) for Emi1. Tumors were considered to be positive when their final staining scores were ≥3 (21). In each specimen, five high-power fields were randomly selected for Ki-67 assessment, together with examination of nuclear staining. To determine the medium percentage of immunostained cells among the total number of cells, >500 cells were counted. To avoid possible technical errors, staining was performed twice, and similar results were achieved. All the aforementioned evaluations were conducted independently by two investigators with identical results.

Cell culture and cell cycle analysis

The human ESCC cell line ECA109 was purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 2 mM L-glutamine and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin mixture (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were fixed in 70% ethanol for 1 h at 4°C, and then incubated with 1 mg/ml RNase A for 30 min at 37°C for cell cycle analysis. Next, cells were stained with propidium iodide (50 mg/ml; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed using a flow cytometer (FACScan; BD Biosciences) and CellQuest Pro Acquisition and Analysis software (BD Biosciences).

siRNA and transfection

The pSilencer 4.1-CMV Emi1-siRNA expression vectors were constructed by incorporating the siRNA targeting nucleotide residues AAGCACTAGAGACCAGTAGAC (Emi1-si1) and ACTTGCTGCCAGTTCTCA (Emi1-si2) in the pSilencer 4.1-CMV vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). ECA109 cells were seeded the day preceding transfection using RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal calf serum but without antibiotics. Transient transfection of Emi1-siRNA and control siRNA vectors was conducted using Lipofectamine® LTX & PLUS™ reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in Opti-MEM® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), as suggested by the manufacturer. Cells were incubated with the pSilencer vectors and Lipofectamine® LTX & PLUS™ reagent complexes for 4 h at 37°C, and harvested 48 h post-transfection. The experiments were repeated three times.

Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 assay

Cell proliferation was detected by the commercial CCK-8 method (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Kumamoto, Japan), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Shortly, cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture cluster plates at a concentration of 2×104 cells/well in volumes of 100 µl, and cultured overnight. CCK-8 reagent was added to a subset of wells containing cells under different treatments, and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The absorbance was next quantified at 450 nm with an automated plate reader.

Western blot analysis

Tissues and cells were rapidly homogenized in a homogenization buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% Nonidet ™ P-40, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 10 µg/ml aprotinin, 0.5 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, prior to be centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min to collect the supernatant. Protein concentrations were measured with a Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). 2X SDS loading buffer was used to dilute the supernatant, which was next boiled. Proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% dried skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20, containing 20 mM Tris, 0.05% Tween 20, and 150 mM NaCl. Following 2 h-incubation at room temperature, the membranes were incubated overnight with the following antibodies: Anti-Emi1 (1:500; cat. no. sc-30182), anti-cyclin A (1:500; cat. no. sc-751), anti-cyclin B1 (1:500; cat. no. sc-25764), anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-56) and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-25778). All the above primary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Horseradish peroxidase-linked IgG (cat. no. sc-2030; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was used as a secondary antibody. The immunoreactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (NEN Life Science Products, Inc., Boston, MA, USA), and exposed to X-ray films, which were then scanned using a Molecular Dynamics densitometer (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Chalfont, UK) and the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE, USA). The experiments were repeated on three separate occasions.

Statistical analysis

The statistical software Stata version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The association between Emi1 protein expression and clinicopathological factors was analyzed using the χ2 test. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was employed for analysis. Multivariate analysis was performed using Cox's proportional hazards model. The risk rate and its 95% confidence interval were recorded for each marker. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

The expression of Emi1 in human ESCC tissue samples

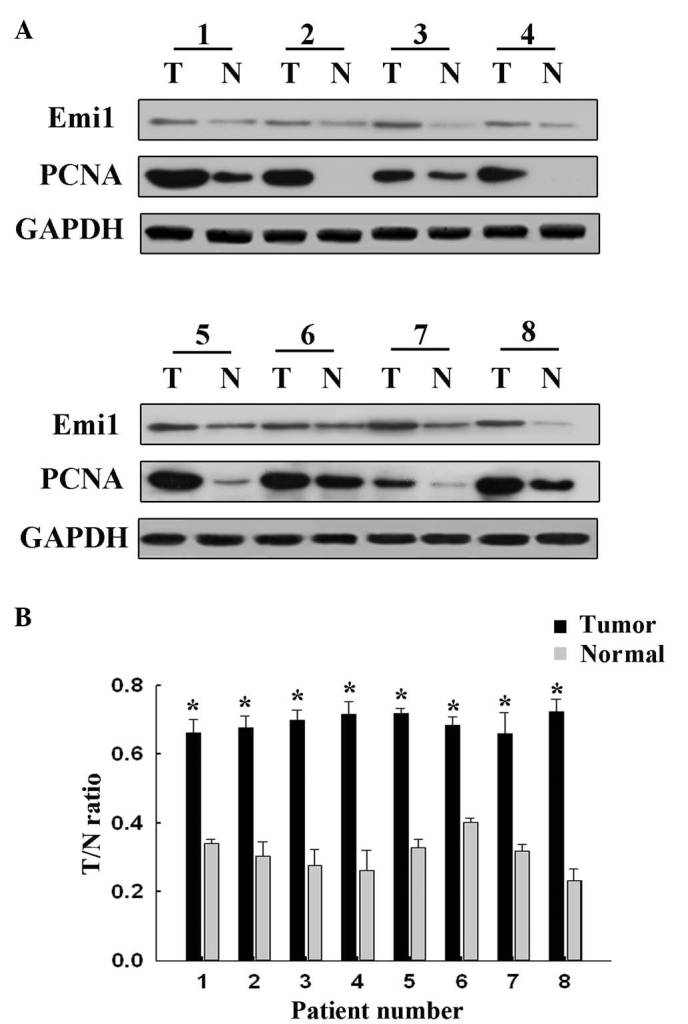

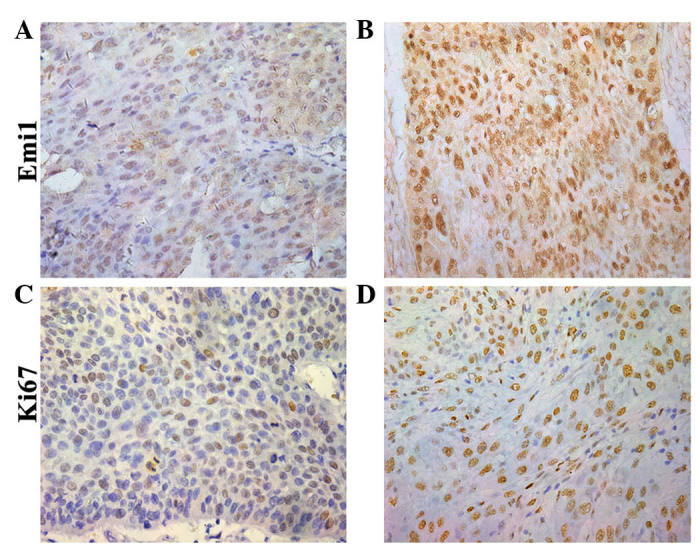

To reveal the role of Emi1 in ESCC, the expression of Emi1 protein was detected by western blot analysis in 8 paired frozen ESCC tumor tissues and para-cancerous tissues. The results revealed that Emi1 expression was significantly increased in 6 of 8 tumors, compared with para-cancerous tissues (P<0.05; Fig. 1). In addition, expression of Emi1 and Ki-67 was simultaneously detected and further verified in 90 ESCC samples by immunohistochemical staining. The results indicated that Emi1 and Ki-67 proteins were overexpressed in ESCC specimens, whereas in the matching para-cancerous tissue samples, their expression was weak or absent (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Emi1 is overexpressed in ESCC, compared with para-cancerous tissues. (A) Western blotting of 8 representative paired samples of ESCC tissues and para-cancerous tissues immunoblotted against Emi1. Whole-cell lysates were prepared from tissue specimens obtained from ESCC and para-cancerous tissues. In 6 of the 8 samples tested, Emi1 expression levels were significantly higher in ESCC than in paired para-cancerous tissues. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen was used as a tumor proliferative marker, while GAPDH was used as a control for protein loading and integrity. (B) Quantification of the results shown in panel A. *P<0.05. ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor-1; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase T, tumor; N, normal.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of Emi1 and Ki-67 in ESCC tissues. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with antibodies against Emi1 and Ki-67, and counterstained with hematoxylin.(A and B) Emi1 reactivity (magnification, ×400). (C and D) Ki-67 staining (SP ×400). (A and C) Well differentiated ESCC specimens displayed (A) weak Emi1 and (C) weak Ki-67 immunostaining. (B and D) Moderate/poor differentiated ESCC tissues exhibited (B) strong Emi1 (B) and (D) strong brown nuclear Ki-67 immunostaining. ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor-1.

Correlation of Emi1 protein expression with clinicopathological variables in human ESCC tissues

The association between Emi1 expression and clinicopathological variables was evaluated. For statistical analysis of Emi1 expression, the ESCC tissue specimens were classified into positive or negative groups, based on their final staining scores. As presented in Table I, Emi1 expression was correlated with histological differentiation (P=0.032) and lymphatic metastasis (P=0.006), while no correlation existed between Emi1 expression and other prognostics factors, including age, gender, tumor diameter and tumor depth. Furthermore, a positive correlation existed between Emi1 and Ki-67 expression (which is indicative of proliferative activity) in the majority of specimens (P=0.028).

Table I.

Association between Emi1 protein expression and clinicopathological features of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma specimens.

| Emi1 expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Cases (n) | Negative (final score, 0–2; n=32) | Positive (final score 3–7; n=58) | P-value |

| Age, years | 0.244 | |||

| ≤60 | 46 | 19 | 27 | |

| >60 | 44 | 13 | 31 | |

| Gender | 0.120 | |||

| Male | 55 | 23 | 32 | |

| Female | 35 | 9 | 26 | |

| Histological differentiation | 0.032a | |||

| Well | 20 | 12 | 8 | |

| Moderately | 50 | 15 | 35 | |

| Poorly | 20 | 5 | 15 | |

| Lymphatic metastasis | 0.006a | |||

| Positive | 23 | 9 | 34 | |

| Negative | 67 | 23 | 24 | |

| Tumor diameter, cm | 0.755 | |||

| ≤5 | 80 | 28 | 52 | |

| >5 | 10 | 4 | 6 | |

| Tumor depth | 0.079 | |||

| T1 | 7 | 3 | 4 | |

| T2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| T3 | 22 | 7 | 15 | |

| T4 | 55 | 17 | 38 | |

| Ki-67 expression, % | 0.028a | |||

| ≤0.78 | 45 | 21 | 24 | |

| >0.78 | 45 | 11 | 34 | |

Statistical analyses were performed with the Pearson's χ2 test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor-1.

Prognostic significance of Emi1 expression in human ESCC samples

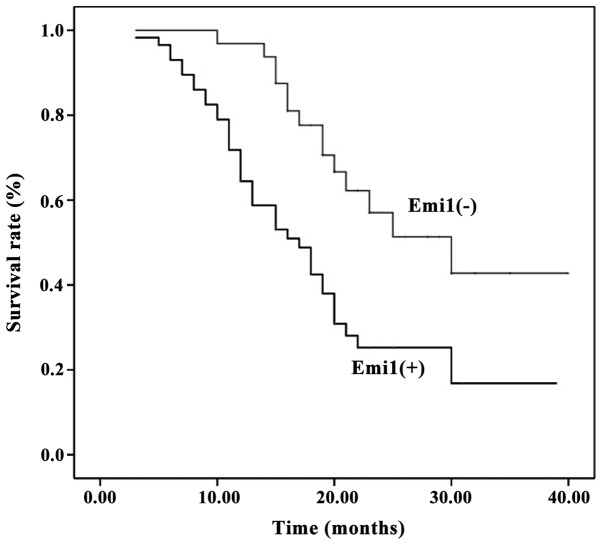

Survival information was available for all patients at the end of clinical follow-up. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for univariate analysis demonstrated that Emi1 protein overexpression resulted in a poor survival rate (P<0.05) (Fig. 3). According to the Cox's proportional hazards regression model, Emi1 expression, Ki67 expression and lymphatic metastasis were independent prognostic factors of poor prognosis in ESCC patients (Table II).

Figure 3.

Prognostic significance of Emi1 expression in human ESCC samples. Kaplan-Meier survival curves revealed that, compared with low expression of Emi1, its overexpression was correlated with poor survival in ESCC patients (P=0.001, log-rank test). Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor-1; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Table II.

Contribution of various potential prognostic factors to survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.143 | 0.655–1.995 | 0.638 |

| Gender | 0.898 | 0.483–1.668 | 0.733 |

| Histological differentiation | 0.641 | 0.416–1.624 | 0.571 |

| Tumor diameter | 1.485 | 0.652–3.383 | 0.346 |

| Tumor depth | 1.171 | 0.800–1.713 | 0.416 |

| Lymphatic metastasis | 0.822 | 0.421–0.976 | 0.018a |

| Emi1 expression | 1.967 | 1.024–3.782 | 0.042a |

| Ki-67 expression | 3.047 | 1.554–5.973 | 0.001a |

Statistical analyses were performed with the log-rank test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor-1.

Emi1 is involved in ESCC cell proliferation

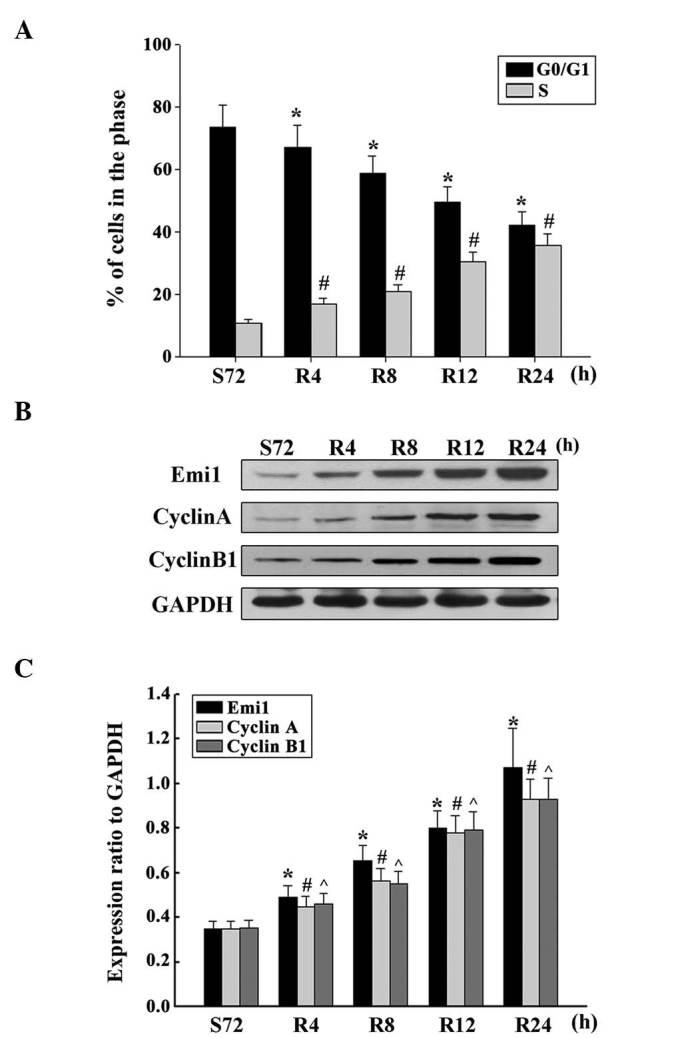

To demonstrate whether Emi1 expression was cell cycle-dependent in ESCC cells, the cell cycle was analyzed following serum starvation and upon re-feeding with serum. ECA109 cells were arrested in the G1 phase by serum deprivation for 72 h, and the percentage of cells in the G1 phase increased from 39.08 to 73.35% under these conditions (Fig. 4A). Upon serum addition, the cells were released from the G1 phase and reentered the S phase. As expected, the expression of Emi1 increased as early as 4 h post-serum stimulation in ECA109 cells. Additionally, the expression of cyclins A and B was upregulated (Fig. 4B and C). These results indicate that Emi1 is important role in the regulation of cell proliferation.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of Emi1 and cell cycle-related molecules in proliferating esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. (A) ECA109 cells were synchronized at G1, and induced to progress into the cell cycle by serum addition at 0, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h. Upon cell cycle progression induction, the majority of cells were in the S phase. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments *,#P<0.01 vs. control (S72 h). (B) ECA109 cells were serum starved for 72 h, and following serum addition, cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by western blotting using antibodies against Emi1, cyclin A and cyclin B1. GAPDH was used as a control for protein loading and integrity. (C) Ratio of Emi1, cyclin A and cyclin B1 protein levels to those of GAPDH for each time point, as analyzed by densitometry. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=3). *,#,^P<0.01, vs. control (S72 h). S, serum starvation; R, serum addition; Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor-1; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

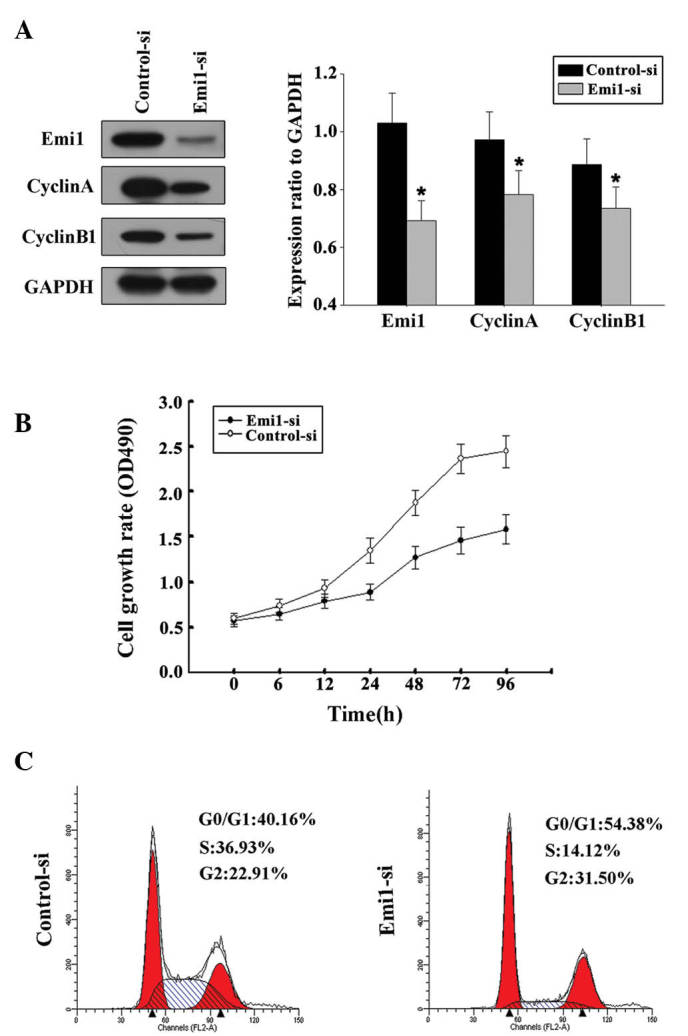

siRNA targeting Emi1 inhibits ESCC cell proliferation

By transfecting ECA109 cells with Emil-siRNA or control siRNA, the influence of Emil on ESCC cell proliferation was further evaluated. In the present study, two siRNAs targeting Emi1 (Emi1-si1 and Emi1-si2) were tested, and the efficiency of Emi1 gene silencing was measured by immunoblotting. The results demonstrated that Emi1-si1 exerted a better silencing effect. Decreased expression of cyclins A and B was detected in Emi-si1 (Fig. 5A). This result was in agreement with a previous study that reported that Emi1 promoted mitotic entry to enable accumulation of cyclins A and B1 (15). Flow cytometry confirmed that Emi1-si could inhibit the cell cycle at the G1-S transition (Fig. 5B). Silencing of Emi1 led to a significant inhibition of the rate of cell growth (Fig. 5C). These findings further suggested that Emi1 may be involved in the regulation of the G1-S transition, which could be responsible for the increased growth rate of ESCC cells.

Figure 5.

Silencing Emi1 expression suppressed the proliferation of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells and the expression of cell cycle-related molecules in these cells. (A) ECA109 cells were transiently transfected with siRNA targeting Emi1 (Emi1-si1 and Emi1-si2) or with a scrambled control siRNA sequence (control-si) for 48 h, and immunoblot analysis of Emi1, cyclin A, cyclin B1 and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was then performed, *P<0.05 vs. control. (B) The growth curve of ECA109 cells treated with Emi1-si1 was compared with that of control-si-treated cells by Cell Counting Kit-8 assay at the indicated time points. Silencing Emi1 resulted in a significant inhibition in cell growth rate (P=0.001). (C) At 48 h post-transfection, cells were stained with propidium iodide for analysis of their DNA content by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Flow cytometry demonstrated that Emi1 inhibited the cell cycle at the G1/S transition. Emi1, early mitotic inhibitor-1; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; si, small interfering; OD, optical density.

Discussion

Thanks to the advances in molecular and cellular biology of tumors, it is well known that the occurrence of EC is partly due to acquired alterations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (4). Cell proliferation, differentiation and cell cycle control disorders are important features in cancer (1). Misregulation of the G1-S transition is an essential component of the cellular transformation process in the cell cycle, and G1-S regulatory defects have been reported in numerous types of human malignancies (22–24).

Emi1 was firstly identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen for F-box proteins using S-Phase kinase-associated protein 1 as bait (17). In mammalian cells, Emi1 levels are regulated during the cell cycle, with its transcription being induced at the G1-S transition under the control of E2F, which is required to stabilize cyclins A and B, and enables cells to initiate the S phase (18). A previous study indicated that Emi1 is accumulated in ovarian clear cell carcinoma (25), and Liu et al (26) reported that Emi1 overexpression may be a poor prognostic marker for breast carcinoma patients. These findings suggested that the Emi1 gene may be involved in human cell cycle disorders and may lead to oncogenesis.

To the best of our knowledge, Emi1 expression in ESCC specimens has not been actively studied thus far. The present study is the first to report that Emi1 protein is overexpressed in human ESCC, and analyze a possible association between Emi1 expression and clinicopathological factors and prognosis of patients with ESCC. In the present study, immunoblotting examined the protein expression levels of Emi1 in ESCC specimens and para-cancerous tissues. Furthermore, the expression of Emi1 was investigated to confirm the participation of Emi1 in tumor progression by immunohistochemical staining. High expression of Emi1 as a useful marker of tumor proliferative activity (27,28) was correlated with overexpression of Ki-67. Therefore, increased Emi1 levels may be closely associated with the pathogenesis of ESCC. In addition, the association between Emi1 expression and clinicopathological variables and patient prognosis was evaluated. The results revealed that Emi1 expression was strongly correlated with histological differentiation and lymphatic metastasis. The results of survival analysis demonstrated that high expression of Emi1 was strongly correlated with poor prognosis, while multivariate analysis revealed that high expression of Emi1 was an independent unfavorable prognostic factor. These findings indicated that Emi1 may be a reliable factor of prognosis in patients with EC.

The expression of Emi1 during cell cycle progression was further detected in ESCC cells in vitro. The results indicated that the expression of Emi1 was upregulated during the G1-S phase transition. These results confirmed the association of Emi1 expression with ESCC development. Furthermore, the present data revealed that silencing Emi1 expression could suppress ECA109 cell proliferation. This observation is consistent with a previous study in which Emi1 promoted mitotic entry and enabled accumulation of cyclins A and B1 (15).

Hsu et al (18) demonstrated that upregulation of Emi1 at the transcriptional level occurred in various tumors. At the G1-S transition, Emi1 was transcriptionally induced by the transcription factor E2F, which is associated with cell cycle control (18). The E2F signaling pathway is frequently activated in highly proliferative cells, and the central proteins of the retinoblastoma (Rb)/E2F signaling pathway, including p16INK4a, Rb and cyclin D, are frequently mutated in cancer (29). This E2F activation is expected to cause an increase in Emi1 levels.

In summary, the present study demonstrated that Emi1 protein expression was increased in ESCC, and positively correlated with ESCC cell proliferation, indicating that Emi1 may play a key role in ESCC and it is an independent candidate prognostic factor for ESCC patients. However, further studies are required to clarify the molecular mechanisms of Emi1 in the pathogenesis of ESCC.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Baghestani AR. Burden of gastrointestinal cancer in Asia; an overview. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2015;8:19–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng H, Zheng R, Guo Y, Zhang S, Zou X, Wang N, Zhang L, Tang J, Chen J, Wei K, et al. Cancer survival in China, 2003–2005: A population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1921–1930. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lagergren J, Lagergren P. Recent developments in esophageal adenocarcinoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:232–248. doi: 10.3322/caac.21185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson DG, Walker CL. Cyclins and cell cycle checkpoints. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:295–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolgemuth DJ, Roberts SS. Regulating mitosis and meiosis in the male germ line: Critical functions for cyclins. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:1653–1662. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kronja I, Orr-Weaver TL. Translational regulation of the cell cycle: When, where, how and why? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366:3638–3652. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Fei M, Cheng C, Zhang D, Lu J, He S, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Shen A. Jun activation domain-binding protein 1 negatively regulate p27 kip1 in non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:460–467. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.3.5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song Y, Zhao C, Dong L, Fu M, Xue L, Huang Z, Tong T, Zhou Z, Chen A, Yang Z, et al. Overexpression of cyclin B1 in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells induces tumor cell invasive growth and metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:307–315. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeno S, Noguchi T, Kikuchi R, Uchida Y, Yokoyama S, Müller W. Prognostic value of cyclin B1 in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:2874–2881. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nozoe T, Korenaga D, Kabashima A, Ohga T, Saeki H, Sugimachi K. Significance of cyclin B1 expression as an independent prognostic indicator of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:817–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chetty R, Simelane S. p53 and cyclin A protein expression in squamous carcinoma of the oesophagus. Pathol Oncol Res. 1999;5:193–196. doi: 10.1053/paor.1999.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernis C, Vigneron S, Burgess A, Labbé JC, Fesquet D, Castro A, Lorca T. Pin1 stabilizes Emi1 during G2 phase by preventing its association with SCF(betatrcp) EMBO Rep. 2007;8:91–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller JJ, Summers MK, Hansen DV, Nachury MV, Lehman NL, Loktev A, Jackson PK. Emi1 stably binds and inhibits the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome as a pseudosubstrate inhibitor. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2410–2420. doi: 10.1101/gad.1454006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moshe Y, Bar-On O, Ganoth D, Hershko A. Regulation of the action of early mitotic inhibitor 1 on the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome by cyclin-dependent kinases. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16647–16657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.223339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reimann JD, Gardner BE, Margottin-Goguet F, Jackson PK. Emi1 regulates the anaphase-promoting complex by a different mechanism than Mad2 proteins. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3278–3285. doi: 10.1101/gad.945701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reimann JD, Freed E, Hsu JY, Kramer ER, Peters JM, Jackson PK. Emi1 is a mitotic regulator that interacts with Cdc20 and inhibits the anaphase promoting complex. Cell. 2001;105:645–655. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu JY, Reimann JD, Sørensen CS, Lukas J, Jackson PK. E2F-dependent accumulation of hEmi1 regulates S phase entry by inhibiting APC (Cdh1) Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:358–366. doi: 10.1038/ncb785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margottin-Goguet F, Hsu JY, Loktev A, Hsieh HM, Reimann JD, Jackson PK. Prophase destruction of Emi1 by the SCF (betaTrCP/Slimb) ubiquitin ligase activates the anaphase promoting complex to allow progression beyond prometaphase. Dev Cell. 2003;4:813–826. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y, Tang Q, Ni R, Huang X, Wang Y, Lu C, Shen A, Wang Y, Li C, Yuan Q, et al. Early mitotic inhibitor-1, an anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome inhibitor, can control tumor cell proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma: Correlation with Skp2 stability and degradation of p27(Kip1) Hum Pathol. 2013;44:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masunaga R, Kohno H, Dhar DK, Ohno S, Shibakita M, Kinugasa S, Yoshimura H, Tachibana M, Kubota H, Nagasue N. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression correlates with tumor neovascularization and prognosis in human colorectal carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4064–4068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth JA, Cristiano RJ. Gene therapy for cancer: What have we done and where are we going? J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:21–39. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roncalli M, Bosari S, Marchetti A, Buttitta F, Bossi P, Graziani D, Peracchia A, Bonavina L, Viale G, Coggi G. Cell cycle-related gene abnormalities and product expression in esophageal carcinoma. Lab Invest. 1998;78:1049–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gütgemann I, Lehman NL, Jackson PK, Longacre TA. Emi1 protein accumulation implicates misregulation of the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome pathway in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:445–454. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Wang H, Ma J, Xu J, Sheng C, Yang S, Sun L, Ni Q. The expression and prognosis of Emi1 and Skp2 in breast carcinoma: Associated with PI3K/Akt pathway and cell proliferation. Med Oncol. 2013;30:735. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheri A, Dowsett M. Developments in Ki67 and other biomarkers for treatment decision making in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 10):x219–x227. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He WL, Li YH, Yang DJ, Song W, Chen XL, Liu FK, Wang Z, Li W, Chen W, Chen CY, et al. Combined evaluation of centromere protein H and Ki-67 as prognostic biomarker for patients with gastric carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harbour JW, Dean DC. The Rb/E2F pathway: Expanding roles and emerging paradigms. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2393–2409. doi: 10.1101/gad.813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]